On the twentieth anniversary of China’s WTO accession, there has been considerable discussion of the failure of the WTO to transform China in the ways many scholars and policymakers expected. At the time of China’s accession, it was widely assumed that China’s membership in the trade body – by fueling exports, growth, and economic development – would help to foster greater political and economic liberalization within the country. Instead, however, just the opposite has occurred. Despite an extraordinary boom in China’s exports, which has in turn fueled remarkably rapid economic growth and development, after an initial period of relative opening, China has more recently gone in the opposite direction of rising authoritarianism and greater state intervention in the economy (Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Rithmire and Tsai2021; Weiss, Reference Weiss2019).

If the conventional wisdom was wrong about the impact of the WTO on China, it has been equally wrong about the impact of China on the WTO. In contrast to prevailing expectations that China would be smoothly incorporated into global trade governance, the rise of China – and the corresponding decline in the relative power of the US – have created serious problems for the functioning of the multilateral trading system. The WTO’s core negotiation function has collapsed, as evident in the breakdown of the Doha Round and the repeated failure of subsequent negotiating efforts. Its dispute settlement and enforcement mechanism is in jeopardy amid the US blockage of Appellate Body appointments. The US has abandoned its traditional leadership role in the multilateral trading system, turning away from trade multilateralism in favor of aggressive unilateralism, arbitrarily imposing tariffs on its trading partners, and launching a trade war with China. The rules-based multilateral trading system is now in danger of collapse.

China’s rise has precipitated a crisis within the multilateral trading system. Many commentators have blamed the current crisis on the inability of the WTO to adequality address China’s model of state-sponsored capitalism (Petersmann, Reference Petersmann2019; Wu, Reference Wu2016). But that framing of the problem is, I argue, potentially misleading. The primary complaints that the US and others have about China’s trade policy – such as its use of industrial subsidies, forced technology transfer, intellectual property violations, and so forth – are not unique to China’s more heavily state-controlled economy. Instead, these are typical features of the developmental state, commonly deployed by states seeking to catch up with more advanced economies and used by most successful late developers. The more fundamental conflict thus centers on how the multilateral trading system deals with a developing country that is also an economic powerhouse.

The question of how China should be classified and treated under global trade rules has become an acute source of conflict in the trade regime. The China paradox – the fact that China is simultaneously both a major economic heavyweight as well as a developing country – has created significant challenges for global trade governance. Developing countries are afforded special status in the multilateral trading system, and allowed greater policy space for state intervention to foster economic growth and development, including “special and differential treatment” in WTO agreements. But extending such status to China has become increasingly controversial as its economic weight has grown. The US and other advanced-industrialized states fiercely object to providing special treatment to a country they view as a major economic powerhouse and competitor. This fundamental conflict over what scope China should be allowed for a developmental state has paralyzed global trade governance and led to a breakdown in rule-making. It was a central factor in the collapse of the Doha Round, and it has remained an acute and persistent source of conflict in subsequent negotiating efforts at the WTO since then (Efstathopoulos, Reference Efstathopoulos2016; Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2016; Narlikar, Reference Narlikar2020; Sinha, Reference Sinha2021; Weinhardt, Reference Weinhardt2020).

At the same time, the rise of China and other emerging powers has sharply curtailed the US’s “institutional power” (Barnett and Duvall, Reference Barnett and Duvall2005) – the ability to shape global institutions and rules to guide, steer and constrain the actions of others. The US constructed the GATT/WTO, which served as a channel for the projection of American power, and its rules have reflected US primacy. Now, however, the rise of China has significantly constrained the US’s power over the core institution and rules governing trade. The US’s ability to dominate global trade governance and write the rules of global trade has greatly diminished, leading to an erosion of American support for the multilateral trading system it once created and led.

I Power Shifts and the Global Trade Regime

Upon China’s accession to the WTO, the prevailing expectation was that China would be smoothly integrated into the US-led liberal international economic order because China has benefited from the existence of that order and has an interest in maintaining it. It was assumed not only that the multilateral trading system would continue to function effectively but also that the system would in fact be strengthened by the inclusion of China, given its growing importance in international trade and the global economy more broadly. The conventional wisdom – both at the time of China’s accession and in the ensuing years of its emergence as a major economic power – has been that China is a supporter of, and would therefore seek to maintain, the international economic order that has facilitated and enabled its rise (Cox, Reference Cox2012; Nye, Reference Nye2015; Snyder, Reference Snyder2011; Xiao, Reference Xiao, Friedman, Oskanian and Pardo2013). Many have argued that China’s objectives are fundamentally status-quo-oriented and system-supporting, and that its rise is accordingly “not threatening to the order’s basic arrangements or principles” (Brooks and Wohlforth, Reference Brooks and Wohlforth2016: 100; see also Kahler, Reference Kahler2010). In an era of global economic interdependence, the assumption that all states have an interest in maintaining the system has led many to conclude that the US and China will find ways to cooperate and jointly participate in the management of the international economic architecture, and collective action will prevail to preserve an open, liberal trading order (Cox, Reference Cox2012; Ikenberry, Reference Ikenberry2011; Nye, Reference Nye2015; Snyder, Reference Snyder2011; Xiao, Reference Xiao, Friedman, Oskanian and Pardo2013).

For many, a key factor in determining whether power shifts will result in conflict or cooperation is whether the US and other established powers adapt to the rise of China and other new powers by integrating them into existing institutions and their decision-making structures – meaning giving China and other emerging powers a seat at the table that reflects their economic weight and allowing them to assume a leadership role in global economic institutions like the WTO (Kahler, Reference Kahler2016; Paul, Reference Paul and Paul2016b; Zangl et al., Reference Zangl, Heußner, Kruck and Lanzendörfer2016). Many have argued that the future of global economic governance hinges on the willingness of the US to redistribute authority, make room for rising powers like China, and develop a system of shared leadership that accommodates their demands for greater voice and authority (Drezner, Reference Drezner2007; Ikenberry, Reference Ikenberry2015; Zakaria, Reference Zakaria2008). The liberal international economic order can be maintained, it has been argued, if rising states are welcomed and incorporated into the power structures of its constitutive institutions. Much is therefore believed to rest on the established powers’ willingness to make adjustments to accommodate rising powers: China will “actively seek to integrate into an expanded and reorganized liberal international order,” provided that the US and other Western states act to reform global institutions to make room for China (Ikenberry, Reference Ikenberry2011: 344). Incorporating China and other rising powers into multilateral institutions like the WTO has been seen as a means to lock in their support for the global economic order (Drezner, Reference Drezner2007; Zakaria, Reference Zakaria2008), while renewing and strengthening multilateralism by making those institutions more inclusive, representative, and legitimate (Vestergaard and Wade, Reference Vestergaard and Wade2015; Warwick Commission, 2008; Zoellick, Reference Zoellick2010).

Existing international relations scholarship has thus assumed that if rising powers are supporters of established governance institutions and successfully incorporated into their decision-making structures, then those institutions will continue to function smoothly and effectively (Ikenberry, Reference Ikenberry2011; Paul, Reference Paul2016a). However, in the case of the WTO, China was incorporated into the institution and subsequently became part of its core power structure. Moreover, as one of the prime beneficiaries of the liberal global trading order, which has enabled the boom in its exports that has propelled its extraordinarily rapid economic growth and development, China has an interest in maintaining the established trading order (Breslin, Reference Breslin2013; Gao, Reference Gao, Picker, Greenacre and Toohey2015; Quark, Reference Quark2013; Scott and Wilkinson, Reference Scott and Wilkinson2013). Yet, China’s rise has nonetheless proven profoundly disruptive to the WTO, leading to the breakdown of the institution’s core negotiation function. The central cause of this breakdown is an intractable conflict over how China should be treated in the multilateral trading system and what scope it should be allowed for a developmental state.

II The China Paradox

China’s rise represents a new bifurcation of economic power and development status in the trading system. Paradoxically, although China is now one of the world’s dominant economic powers, it nonetheless remains a developing country. This seeming contradiction between China’s economic might and its level of development has created significant challenges for the WTO.

As the world’s second-largest economy and its biggest trader, China has emerged as a core center of global economic activity. It is widely projected that China may soon overtake the US as the world’s largest economy. Indeed, measured at purchasing power parity (PPP) rates, China’s GDP ($27 trillion) has already surpassed the US ($23 trillion).Footnote 1 China has replaced America as the top manufacturer and exporter, with export volumes that now vastly exceed those of the US ($2.5 trillion versus $1.7 trillion). Nearly two-thirds of countries trade more with China than the US (Leng and Rajah, Reference Leng and Rajah2019). China has become the largest market for many commodities and consumer goods, home to many of the world’s biggest corporations, and a massive source of outward investment, aid, and lending. It is also establishing itself as the dominant player and technological leader across an increasing range of industrial sectors.

Despite its emergence as an economic powerhouse, however, China continues to face significant development challenges. China’s per capita income, for example, is only 16% of that of the US (with a per capita GNI of just $10,550 compared to $64,550 in the US).Footnote 2 Compared to the world’s other advanced economies, China is thus at a significantly lower level of economic development, measured in terms of average incomes. Even if China crosses the World Bank’s threshold for a “high-income country” (currently defined as a per capita GNI of $12,695) in coming years, it will still continue to lag far behind the US and other advanced economies. One of China’s key overarching goals is to ensure its continued economic development (Gao, Reference Gao, Gao, Raess and Zeng2023), in order to raise its per capita income levels and bring them closer to those in developed countries. It faces immense challenges, however, in trying to do so. These include the challenges of trying to escape the middle-income trap; fostering industrial upgrading to move up the value chain into higher-value-added activities; a rapidly aging population and demographics that are increasingly unfavorable to economic growth; extraordinarily high rates of inequality, especially between rural and urban areas; inadequate social safety nets; relatively low levels of education and human capital, resulting in a massive population of low-skilled, underemployed workers; and rising wages combined with increasing competition from lower-wage countries for low-skilled manufacturing (Rozelle and Hell, Reference Rozelle and Hell2020). The right to development is recognized by the United Nations as a universal human right,Footnote 3 and denying the Chinese population – which includes 600 million people living in poverty on less than $1900 per year (Kuo, Reference Kuo2021) – the right to continued economic development would be a profound injustice.

But given its paradoxical status as both a major economic power and a developing country, the question of how China should be treated under global trade rules has become a major source of controversy (see also Gao, Reference Gao, Gao, Raess and Zeng2023). A core principle of the WTO is that developing countries should be allowed greater scope for state intervention – including tariffs, subsidies, and other trade policy tools – to promote their economic development. This often takes the form of “special and differential treatment” (SDT) providing various flexibilities and exemptions from WTO rules (Weinhardt, Reference Weinhardt2020). There are no established criteria for determining what constitutes a “developing country” at the WTO. Instead, states are allowed to self-designate as developing countries in order to access SDT (Eagleton-Pierce, Reference Eagleton-Pierce2012). China insists that, as a developing country, it is entitled to SDT. However, for the established economic powers, making largely one-sided concessions in opening their markets without equivalent concessions from China is a non-starter. Instead, the US, EU, and others insist that China must take on greater responsibility commensurate with its role as the world’s second-largest economy – meaning undertaking greater commitments to liberalize its market and accept disciplines on its use of subsidies and other trade-distorting policies.

China’s rise has thus heightened the tension between two core principles of the multilateral trading system. The first is the principle of reciprocity – that trade negotiations should take place based on a reciprocal exchange of concessions, with participants gaining roughly equivalent benefits or, conversely, incurring roughly equal costs (Brown and Stern, Reference Brown, Stern, Narlikar, Daunton and Stern2012). Closely related to this is the notion of creating universal rules – at least for the world’s major trading states – with rights and obligations applying equally to all participants. The principle of reciprocity and universality, however, coexists somewhat uneasily with a second key principle of the trading system – preferential treatment for developing countries. The latter stems from the recognition that equal treatment is not equal for countries at different levels of development. Dating back to Alexander Hamilton’s (1790) call for the US to adopt infant industry protections to enable the expansion of its manufacturing sector in the context of British industrial supremacy, there has been skepticism about free trade as a path to development and the capacity of developing countries to catch-up with more advanced economies without interventionist trade policy measures such as tariffs and subsidies.

SDT is based on the principle that developing countries should not be expected to engage in a reciprocal exchange of concessions with more advanced economies, or assume the same obligations (Hannah and Scott, Reference Hannah, Ryan and Scott2017). Instead, rather than universal rules applying equally to all countries, countries at lower levels of development should be granted greater flexibility (or “policy space”) to protect their domestic markets and promote the development of their exports, firms, and industries, as well as given preferential and non-reciprocal access for their exports to developed country markets (Narlikar, Reference Narlikar2020; Singh, Reference Singh2017). SDT is seen as an important means for the WTO to address the needs of developing countries and aid in fostering global development. While the notion of providing additional policy space to developing countries has never been uncontroversial (Hannah et al., Reference Hannah, Ryan and Scott2017), with the rise of China as a major economic power that is also a developing country, it has now emerged as a central source of conflict within the trading system.

The conflict rests on whether the rules should be universal and concessions reciprocal, or China should have access to SDT in recognition of its status as a developing country, along with continued scope for state intervention to promote its economic development. At the heart of this conflict are competing interests, as well as ideas of fairness. From the perspective of the US and other advanced-industrialized states, fairness means a level playing field undistorted by state intervention, with universal rules applying equally to all and the reciprocal exchange of concessions in multilateral trade negotiations. But from China’s perspective, what those states define as a level playing field is, in fact, one that serves to perpetuate their industrial and economic supremacy.

For China, it is considered vital to maintain the policy space needed to engage effectively in industrial policy and foster industrial upgrading, in order to continue its process of economic development and avoid becoming stuck in the middle-income trap. China’s development model rests on an active state engaged in supporting the competitiveness of national firms and industries and helping them to move up the value chain into higher value-added activities thereby boosting growth, incomes, and the quality of employment (Lin and Chang, Reference Lin and Chang2009; Stiglitz et al., Reference Stiglitz, Esteban and Lin2013). An interventionist state remains central to its strategy for continued development, as evident in its Made in China 2025 industrial policy program (Ban and Blyth, Reference Ban and Blyth2013; Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2018). China’s emphasis on state intervention is backed by the experience of other successful late developers (Chang, Reference Chang2002).

Indeed, even the US and other advanced-industrialized states relied on state intervention and employed a range of protectionist policies during their own process of economic development (Kupchan, Reference Kupchan2014). This included using tariffs and subsidies to foster the growth of infant industries and sequence their integration into the global economy; aggressively adopting technology from more advanced countries; and controlling the inflow of foreign investment to direct it toward the goals of national development (Chang, Reference Chang2002; Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2008; Wade, Reference Wade2003). Moreover, even from a position of global economic dominance, the US has continued to deviate from the principles of free trade and make use of protectionism when it serves its interests (Block and Keller, Reference Block and Keller2011; Schrank and Whitford, Reference Schrank and Whitford2009; Weiss, Reference Weiss2014). From China’s perspective, in seeking to preserve the scope for state intervention to promote its industrial development, it is simply seeking to follow in the footsteps of the US and other advanced-industrialized states, while those countries are seeking to “kick away the ladder” by preventing China from using many of the same policy tools that were vital to their own growth and development (Chang, Reference Chang2002; Stiglitz and Greenwald, Reference Stiglitz and Greenwald2014).

However, while China remains a developing country and continues to face significant development challenges, it is now an extremely large and immensely powerful force in the global economy and is seen by the US and many other advanced economies as a major competitive threat. The justification for allowing developing countries greater policy space is to enable them to catch up with more advanced economies. But opponents argue that China has gone beyond “catching up” to crushing its established competitors in many industries. Rail equipment – which has been prioritized as a key strategic sector under China’s Made in China 2025 program – provides an illustration. After years of receiving subsidized financing to undercut its competitors and facilitate its global expansion, China’s state-owned CRRC now dominates the global rail industry, with annual revenues of $34 billion, dwarfing its rivals, Germany’s Siemens (with $10 billion in annual revenue), France’s Alstom ($9 billion), Canada’s Bombardier ($8 billion), and the US’s GE ($4 billion) (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2021a). Seeking to better compete with CRRC, Siemens, and Alstom attempted to merge in 2018–19, but the merger was blocked by EU competition authorities, while both Bombardier and GE have been forced to sell off their rail businesses. Access to cheap, subsidized loans similarly facilitated the global expansion of Huawei, which is now the world’s largest telecoms equipment company and the global leader in 5G technology (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2021a).

This clash between US demands for reciprocity and universal rules, on the one hand, and China’s demands for special and differential treatment as a developing country, on the other, was at the center of the Doha Round breakdown, and it has remained an enduring issue of conflict severely impeding the WTO’s negotiation function. But this dispute goes beyond SDT, narrowly defined. It is also more broadly about what commitments China should be expected to assume, how much space China should be allowed for state intervention to promote continued economic growth and development, and whether China should be forced to accept new disciplines or restrictions on its use of industrial policy more broadly.

III Breakdown of the WTO’s Negotiation Function

The dispute over how China should be treated under global trade rules has played a central role in the breakdown of the WTO’s negotiating function, starting with the collapse of the Doha Round. Extensive SDT for developing countries was a key promise of the Doha “Development” Round. The Ministerial Declaration launching the Round contained references to SDT across virtually all areas of the negotiations. These stated commitments to SDT could have proven little more than empty promises. However, over the course of the round, developing country coalitions, such as the G20 and G33, led by Brazil and India – and backed by the weight of China – transformed developing countries into a far more effective negotiating force than ever before (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2016; Narlikar, Reference Narlikar2010). Consequently, developing countries were able to secure substantial SDT in the draft texts of the proposed agreement, including weaker tariff-reduction formulas in agriculture and manufactured goods, as well as substantial flexibilities.

By the latter stages of the round, the prospect of extending such extensive SDT to China in particular had become untenable for the US, provoking protests from Congress as well as business and farm lobby groups. From the US’s perspective, it would be making substantial, meaningful concessions in opening its market – including significantly cutting its tariffs and its agricultural subsidies – but see little from China in return (US, 2008). As one US negotiator put it, “we’d be giving everything and getting nothing.”Footnote 4 The US had become unwilling to extend that kind of less-than-full-reciprocity to a country that it now sees as a major economic competitor and an emerging hegemonic rival.

The US sought to improve the deal by securing additional liberalization commitments from China in manufacturing and agriculture. It pressed China to participate in “sectorals” (aggressive tariff reduction in specific industrial sectors) in two key areas of US competitiveness – chemicals and industrial machinery. The US also pressed China to agree not to use its special product exemptions in agriculture against specific products of export interest to the US – namely, cotton, wheat, and corn – in order to guarantee the US market access gains in those areas. The US also sought a restrictive operationalization of the special safeguard mechanism (SSM) in agriculture in order to ensure that its market access gains were not eroded.

China proved far less malleable, however, than the US anticipated. From Beijing’s perspective, the US’s demands were a violation of the implicit bargain struck during China’s accession, where in exchange for the deep concessions China was forced to make in opening its market, it was promised that relatively little new liberalization would be required of it during the Doha Round. From China’s point of view, the US was now trying to renege on its earlier promises. China also saw the US’s demands as a violation of the development mandate of the Round, and the promise that the final agreement would be reached on the basis of “less than full reciprocity” in favor of developing countries. China argued that the US was now unfairly seeking to change the terms of the deal and singling it out for further tariff cuts when its tariffs were already far lower than most other developing counties. As a result, China refused to agree to the sectorals sought by the US in chemicals and industrial machinery, which are key sectors China is trying to foster as part of its industrial upgrading strategy. If it opened those sectors, relinquishing its infant industry protections, Chinese policymakers feared they would be undercut by foreign competition, impeding its continued economic development. Similarly, on agriculture, China is eager to ensure that it retains its ability to use trade policy tools to protect vulnerable (and potentially politically volatile) parts of its population – such as poor, peasant farmers – leading China to refuse to concede to US demands on agriculture, instead insisting on a maximal definition of the SSM and that it retain full use of its special product exemptions.

The Doha negotiations broke down in 2008, ostensibly due to conflict over the design of the SSM. Yet the deeper cause of the Doha breakdown was this fundamental conflict over the US’s desire to “rebalance” the deal by securing greater access for its exports to the Chinese market. China stood firm, refusing to give in to the US and rebuffing its demands for additional market opening. In doing so, China showed that had sufficient power to refuse to concede to US demands that it viewed as fundamentally against its own interests. The result has been a stalemate. The Doha Round was officially declared at an impasse in 2011, and the 2015 Nairobi Ministerial Declaration acknowledged that most members now consider the round dead (Scott and Wilkinson, Reference Scott and Wilkinson2020).

The US argues that it is no longer appropriate to treat China and other large emerging economies like other developing countries. To quote a former US Trade Representative, “the size and growth trajectories of the emerging economies combined with the fact that some are now leading producers and exporters in key sectors … set them apart” (Schwab, Reference Schwab2011). According to the President’s 2011 Trade Agenda:

The remarkable growth of emerging economies like China, India, and Brazil has fundamentally changed the landscape … [W]e are asking these emerging economies to accept responsibility commensurate with their expanded roles in the global economy. … Countries with rapidly expanding degrees of global competitiveness and exporting success should be prepared to contribute meaningfully towards trade liberalization.Footnote 5

The US insists that the WTO differentiate among developing countries in determining access to SDT, arguing that many emerging economies have “graduated” from developing country status and need to engage in a more reciprocal exchange of concessions. US officials and industry representatives make it clear that their primary concern is China, whose economic might and perceived geopolitical threat vastly overshadow that of other large emerging economies. The US has refused to accept new obligations unless greater liberalization is required of China and the other large emerging economies (US, 2011). Yet China staunchly maintains that, as a developing country, it is entitled to SDT and has refused to make concessions to appease the US. With the US and China at loggerheads, WTO negotiations have been beset by repeated deadlock.

Since the Doha collapse, the focus of the WTO has shifted from seeking to conclude a broad-based, comprehensive trade round to trying to craft narrower, targeted agreements on specific trade issues, such as agricultural subsidies and fisheries subsidies. Yet the same conflict over how China and other emerging economies should be classified and treated under multilateral trade rules has persisted and continues to impede efforts to construct new and expanded WTO rules (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2019).

This conflict has only grown deeper and more entrenched, with the US stepping up its criticism of allowing China and other large emerging economies to access SDT. Under the Trump administration, the issue became one of the US’s chief complaints about the WTO. As a White House memorandum put it, “the WTO continues to rest on an outdated dichotomy between developed and developing countries that has allowed some WTO members to gain unfair advantages in the international trade arena.”Footnote 6 Indeed, this alleged fundamental “unfairness” of the WTO became a key justification for the US to turn away from trade multilateralism and embrace aggressive unilateralism (in blatant violation of WTO rules) under President Trump.

The Trump administration used various carrots and sticks to pressure several countries – including Brazil, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore – to agree to forgo SDT in future WTO agreements. Brazil, for example, agreed to relinquish its claim to SDT in exchange for the US supporting its bid to join the OECD, which Brasilia views as essential for attracting foreign investment (Inside U.S. Trade, 2019). The US also unilaterally revoked access to SDT for many emerging economies under its own national trade laws. In 2020, for instance, the US removed 19 emerging economies, including India, Brazil, and South Africa, from its list of developing countries eligible for SDT under US countervailing duty (CVD) law, which allows certain developing countries to be exempt from countervailing duties if the subsidy level or import volume is below a certain threshold (Fortnam, Reference Fortnam2020).

Insisting that WTO agreements should be “reciprocal and mutually advantageous,” the US submitted a proposal in 2019 calling for an end to the practice of allowing states to “self-designate” as developing countries to claim SDT, arguing that this is outdated and “has severely damaged the negotiating arm of the WTO by making every negotiation a negotiation about setting high standards for a few, and allowing vast flexibilities for the many.”Footnote 7 The US proposed that the WTO adopt criteria for SDT, whereby a country would be ineligible for SDT if it is: (1) a member of the OECD, a club of primarily advanced-industrialized states, or in the process of accession; (2) a member of the G20; (3) considered a “high income” country by the World Bank; or (4) accounts for more than 0.5% of world merchandise trade.Footnote 8 These criteria would exclude China from accessing SDT in future WTO negotiations. The US proposal also left open the possibility that additional criteria could be established to exclude countries from SDT in sector-specific negotiations.

The US has enlisted the support of other established powers, such as the EU and Japan. Collectively, as part of the Trilateral Initiative, they have made SDT one of their primary objectives for WTO reform, arguing that: “Overly broad classifications of development, combined with self-designation of development status, inhibits the WTO’s ability to negotiate new, trade-expanding agreements and undermines their effectiveness.”Footnote 9 Together, these states have called on “advanced WTO Members claiming developing country status to undertake full commitments in ongoing and future WTO negotiations.”Footnote 10 The EU has also echoed the US in calling for criteria for SDT and explicitly singled out China as a country that should be excluded from access to SDT.Footnote 11

For its part, however, China has refused to relinquish its claim to SDT, characterizing SDT as a “fundamental” and “unconditional right” of developing countries that is essential for ensuring “equity and fairness” in the WTO system.Footnote 12 In the words of China’s Ambassador to the WTO, “we will never give up the institutional right of special and differential treatment granted to developing countries.”Footnote 13 It has described any attempt to “water down” SDT or differentiate between developing countries as “a certain recipe for intractable deadlock in negotiations.”Footnote 14

This conflict over how much policy space China should be allowed under WTO rules has moved beyond SDT to calls from the US and other advanced-industrialized states for reforms of the WTO to reign in China’s interventionist state and constrain its scope for developmentalist industrial policy. Under the Trilateral Initiative, the US, EU, and Japan have pushed to create stronger WTO disciplines on industrial subsidies, state-owned enterprises, and forced technology transfer – all of which are targeted at China. The established powers have proposed changes to WTO rules to expand the list of prohibited industrial subsidies and establish rules to address subsidies that cause overcapacity. The Trilateral Group has also proposed shifting the burden of proof by requiring states to demonstrate that their subsidy programs are not distorting trade or contributing to overcapacity, as well as advocating more stringent notification standards for industrial subsidies. They have also called for an expanded definition of “public body,” maintaining that the Appellate Body’s excessively narrow interpretation of the term has undermined the effectiveness of WTO subsidy rules vis-à-vis China. Not surprisingly, China has rejected the Trilateral Group’s proposals, which are specifically intended to restrict the very policies Beijing sees as essential to continuing its process of economic development and industrial upgrading. For China, the reforms proposed by the Trilateral Group are evidence that the established powers are trying to block its rise by denying it the tools necessary to catch up with the world’s most advanced economies. Once again, this fundamental dispute over how China should be treated in the trade regime and what scope it should be allowed for a developmental state has resulted in an impasse.

IV The Decline of the American Hegemon’s Institutional Power

In international relations theory, it is rising powers that are expected to be the revisionist states – those seeking to change the rules of the system to better reflect their own interests – while the hegemon seeks to defend the existing order and maintain the status quo (Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1981; Kirshner, Reference Kirshner and Blyth2009). Yet within the trading system, China is not a revisionist actor, in the sense of an actor seeking to alter the established rules of the game. On the contrary, China is broadly satisfied with the existing system of global trade rules, which has enabled its remarkable economic rise by providing access to global markets, while still allowing considerable scope for its interventionist state policies to facilitate economic development, industrial upgrading, and catch-up (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2016). China thus has no desire to change the rules – in fact, just the opposite, it is eager to maintain the status quo. Instead, if anything, it is the US that has become the “revisionist” state in the global trade regime, dissatisfied with the inability of the WTO system and its existing rules to adequately address China’s trading practices. The US has therefore sought to alter the rules to eliminate China’s ability to claim special status as a developing country as well as to better discipline its heavy industrial subsidies and other interventionist trade policies, which the US fears are being used to erode its economic dominance. But the US has been unable to force China to capitulate to its demands or accept its desired new rules.

Until now, a distinct and defining aspect of American hegemony has been its dominance of international institutions. Emerging from the Second World War with an overwhelming preponderance of power, the US used its primacy to construct a new and unprecedented institutional order that reflected and reinforced its primacy. The WTO – as “a constitution for the global economy” (Director-General Ruggiero, cited in McMichael, Reference McMichael2004: 166) – was a core pillar of this American hegemonic order, which some have called the “American imperium” (Katzenstein, Reference Katzenstein2005) or the US’s “informal empire” (Panitch and Gindin, Reference Panitch and Gindin2012; Wood, Reference Wood2005).

Rule-making power is a crucial aspect of hegemony: a hegemon is powerful enough to maintain the rules of the system and “play the dominant role in constructing new rules” (Keohane and Nye, Reference Keohane and Nye2011: 37). For over half a century, the American hegemon dominated the GATT/WTO; it had sufficient power to play the dominant role in writing and enforcing the rules of the global trading system, including driving forward the ongoing process of constructing new rules to govern international commerce. But its rule-making power has now been impeded by China, an emerging challenger that has been unwilling to defer to American hegemony in global trade governance. The US and China are engaged in a struggle over the rules of the game – and specifically whether, and how, the rules will apply to China. China has been able to persistently block the US from achieving its objectives in global trade governance. Despite intense pressure, the US has been unable to force China to undertake greater commitments to liberalize its market in the Doha Round, subsequent post-Doha negotiations, or ongoing WTO reform efforts.

To quote Christopher Layne (Reference Layne2018: 110), “in international politics, who rules makes the rules.” In short, China’s rise has profoundly disrupted the US’s ability to make the rules. Even if the US maintains a preponderance of power in the international system, its capacity to direct and steer global trade governance – which until now has been a defining feature of its hegemony – has been severely diminished. In other words, if the US once “ran the system” as John Ikenberry (Reference Ikenberry2015) puts it, that has now been profoundly disrupted: China has proven a significant counterbalance to US power that has substantially weakened American dominance within the WTO.

V Conclusion

It has frequently been assumed that if rising powers are supporters of established governance institutions like the WTO and successfully incorporated into their decision-making structures, then those institutions will continue to function smoothly and effectively. Yet analysis of China’s impact on global trade governance refutes this view. As the world’s largest exporter, China is a beneficiary and supporter of the established trading order. In addition, China has been integrated into the WTO and incorporated into its core power structure, given a seat at the table that reflects its economic weight. The result, however, has been a direct confrontation between the US and China over the rules of global trade that has paralyzed the institution. The clash between the trading system’s two dominant powers has produced a repeated stalemate, which has effectively brought the core negotiating function of the WTO to a halt. This was evident in the breakdown of the Doha Round, and the same fundamental conflict between the US and China has persisted since the Doha collapse and continues to impede the construction of global trade rules, as well as efforts to reform the institution.

This conflict centers on how China should be treated in the trade regime. Under the rules of the WTO, developing countries are generally allowed greater scope for state intervention to foster economic growth and development. Yet while China remains a developing country, it is also now a major economic power. This paradoxical nature of China’s position in the global trading system has created serious challenges for global trade governance. China’s rise represents a new and unprecedented bifurcation of economic power and development status. Despite its considerable aggregate economic might, in terms of the average standard of living of its population, a vast gulf still separates China from the US and other advanced-industrialized states. From China’s perspective, protecting its policy space – including its ability to use interventionist trade measures such as subsidies – is essential to continuing its process of economic development. China’s interest in maintaining its scope for continued development has, however, thrown it into direct conflict with the US and other established economic powers. China maintains that, as a developing country, it should be entitled to special and differential treatment, but many states are unwilling to extend such treatment to a major economic competitor and have instead demanded universal rules and reciprocal concessions from China. Moreover, the US and other established powers have also sought to explicitly constrain China’s scope to use interventionist trade policies through the creation of stricter WTO rules on industrial subsidies and other trade-distorting measures.

For most of its history, the American hegemon played the dominant role in constructing and enforcing the rules of the trading system. But the US’s institutional power – its power over the governing institutions of the trading system and ability to set the rules of global trade – has been severely weakened by contemporary power shifts. US efforts to construct new trade rules in the Doha Round failed due to the rise of China and other emerging powers, who refused to defer to US power or capitulate to its demands. China has similarly blocked US attempts to constrain its policy space through the Trilateral Initiative’s proposed reforms. American efforts to use the multilateral trading system to discipline China’s trading practices have thus been unsuccessful, while the Appellate Body has increasingly interpreted WTO rules in ways that the US perceives as running counter to its interests. Having lost its previous dominance over the core institution and rules governing global trade, the US has grown increasingly dissatisfied with the workings of the multilateral trading system.

This is an important part of the explanation for the US to turn away from the multilateral trading system, its growing dissatisfaction with the system, and its flagrant rule-breaking. This momentous shift cannot simply be explained by the idiosyncrasies of the Trump administration or the rise of populist anti-trade sentiment that both fueled, and was fueled by, his presidency (cf. Kahler, Reference Kahler and Singh2020; Scott and Wilkinson, Reference Scott and Wilkinson2020). These trends both began before and have continued after the Trump administration (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2021b). Explanations centered on domestic politics alone are inadequate to explain the US’s changing orientation towards the multilateral trading system. It is also a response to changes in the distribution of power in the international system. The US is responding not only to a decline in its structural power – that is, its relative economic might vis-à-vis a rising China – but also to a significant decline in its institutional power – its ability to dominate global trade governance and write the rules of global trade.

I Introduction

When China joined the WTO in 2001, it declared that the recently launched Doha Development Round negotiations need to put the interests of developing countries centre stage. The Chinese representative speaking at the country’s first full participation of the General Council Meeting of WTO on 19 December 2001, Mr. Long Yongtu, called for WTO negotiations to facilitate ‘the establishment of a new international economic order which is fair, just and reasonable’, which would entail ‘a balance of interests between developed countries and developing countries, especially conducive to the development of developing countries’ (Mfa.gov.cn, 2001). In its 2019 communication on the Chinese reform proposal for the WTO, China reiterated that the ‘[d]evelopment issue is at the centre of WTO work’ (WTO, 2019a, para. 2.4.1). More than twenty years after its accession to the WTO, it is time to (re)assess the role that China has played on development. Has China indeed positioned itself as a development partner in WTO negotiations that sides with the Global South vis-à-vis the Global North, or has its own economic transformation diminished the scope for a shared agenda on development?

Academics that touch upon China’s role in the WTO vis-à-vis the Global South are so far divided in their assessment: those that emphasise ideological South-South ties tend to portray China’s role as a development partner (Bishop and Zhang, Reference Bishop and Zhang2020; Muzaka and Bishop, Reference Muzaka and Bishop2015; Vieira, Reference Muzaka and Bishop2012), while scholars that highlight political economy dynamics either see mixed or even competing interests vis-à-vis other developing countries (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2021; Vickers, Reference Vickers, Narlikar, Daunton and Stern2014, pp. 268–69). This chapter starts with a brief discussion of these conflicting perspectives on China’s role vis-à-vis the Global South, followed by an examination of China’s negotiating behaviour in the WTO. These patterns in China’s negotiation positions are then compared and contrasted with perceptions of China’s role by other WTO members.

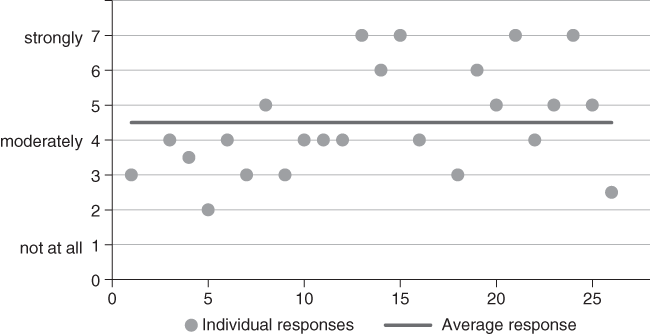

The chapter reveals that while China seeks to align itself politically with the development agenda of the Global South in its bargaining behaviour in Trade Negotiating Committees, perceptions of its role in the WTO are mixed. As the chapter argues, China’s political intention to support a broader development agenda is increasingly undermined by the way in which its larger economic size leads to competition with other developing countries. In particular, China’s distinct economic size increasingly puts it in an ambiguous position when joining other developing country members in their demands to strengthen Special and Differential Treatment (S&D).Footnote 1 The specific conflict lines that arise reflect in part the increasing heterogeneity of the Global South. Three main patterns emerge: First, developing countries that are non-emerging economically are more likely to see China as a competitor for S&D, as compared to other emerging economies or Least Developed Countries (LDCs). Second, developing countries that share the defensive trade policy orientation of the S&D agenda are more likely to perceive China as a development partner as compared to those with a more liberal orientation. Here, conflict lines vary across negotiation issues. Third, the role China plays vis-à-vis the Global South is shaped by the larger context of their specific trade and investment relationship. China thus plays an increasingly contradictory role in the WTO, acting as a development partner for some and as a competitor for other developing countries – dependent on the negotiating issues at stake.

This chapter makes use of the following types of primary sources. First, it relies on official documentation of the WTO’s Trade Negotiations Committee (2001–2019) to assess the negotiation behaviour of China. Second, to reconstruct perceptions of China’s role, the chapter draws on a sample of 33 interviewsFootnote 2 and a survey with 22 officials conducted in Geneva with country representatives at WTO missions, WTO officials, and other trade experts.

II China and the Global South in the WTO: An Overview of the Debate

The existing literature on China’s role in the WTO is primarily interested in its participation in global trade governance, as well as the extent to which it challenges or supports the WTO’s liberal trade order. Questions about China’s relations with the Global South do not take centre stage. The most direct engagement with China’s role vis-à-vis the Global South is part of the literature that analyses bargaining coalitions at the WTO (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2017; Narlikar, Reference Narlikar2010).

Some scholars emphasise that China has tended to side with developing country coalitions because of its growing self-identification with the so-called Global South. In particular, its shared identity as part of the Global South (Nel, Reference Nel2010) or the ‘power South’ (Acharya, Reference Acharya2014, p. 654) leads to ‘pro-Southern’ negotiating behaviour (Muzaka and Bishop, Reference Muzaka and Bishop2015; Vieira, Reference Muzaka and Bishop2012). The decision in the July 2008 mini-ministerial to side with India rather than the US is, for instance, seen as an expression of South-South solidarity ‘when this has required sacrificing a measure of China’s national interests, to support the cause of this developing country coalition’ (Chin, Reference Chin, Narlikar and Vickers2009, p. 143). Johnson and Urpeleinan (Reference Johnson and Urpelainen2020) find that developing countries – including China – exhibit surprising unity at the WTO, an assessment they base on the statistical analysis of 3.600 paragraphs of negotiation-related text on trade and environmental policy.

Southern unity in bargaining coalitions does not necessarily indicate altruistic motives. Political initiatives in favour of developing countries, and Least Developed Countries in particular, are seen to reflect the country’s intention to build soft power by projecting itself as a responsible and benign developing country (Jain, Reference Jain2014, p. 190). A number of authors mention China’s support for LDCs in the WTO (Bhattacharya and Misha, Reference Bhattacharya, Misha and Luolin2015; Jain, Reference Jain2014), as well as statements of support for the LDCs, the group of African, Caribbean and Pacific countries and the African Group (Jain, Reference Jain2014, p. 189). China has also put forward four proposals designed to protect and promote the interest of developing countries in WTO dispute settlement (Liu, Reference Liu2014, p. 127). At the same time, political considerations at times make it difficult for China to demand better market access in developing rather than developed countries, even if economic benefits are involved (Gao, Reference Gao and Deere-Birkbeck2011, p. 166).

Yet, other scholars offer a more cautious assessment of China’s role as a partner of developing countries in WTO negotiations – regardless of the motives. While they acknowledge ideological South-South ties, they claim that China’s economic interests as a major exporter and importer increasingly tend to converge with those of developed countries (Bishop and Zhang, Reference Bishop and Zhang2020, p. 7; Lim and Wang, Reference Lim and Wang2010, p. 1314). This explains why China has not proactively promoted the interests of developing countries in the bargaining coalitions it joined (Lawrence, Reference Lawrence, Eichengreen, Wyplosz and Park2008, pp. 152–153) and remains a reluctant leader in the WTO (Bishop and Zhang, Reference Bishop and Zhang2020). As noted by Vickers, ‘China’s supportive, yet backseat, role in Southern coalitions partly reflects the fact that Beijing actually shared an interest with the US and the EU in seeking greater access to large developing country markets – including Brazil and India – for its manufactured exports’ (Vickers, Reference Vickers, Narlikar, Daunton and Stern2014, pp. 268–269). With regard to the G-20 coalition of developing countries, China, for instance, took a backseat to Brazil and India which exerted much stronger leadership (Lim and Wang, Reference Lim and Wang2010, p. 1316). In other cases, China did not even join developing country coalitions. While China endorsed many of the positions of the NAMA-11 coalition, which includes India and Brazil, it did not join the group to champion its concerns (Vickers, Reference Vickers, Narlikar, Daunton and Stern2014, p. 267). Tu (Reference Tu, Zeng and Liang2013, p. 175) similarly concludes that even if China repeatedly claims that development should be at the heart of the Doha round, it is seen as ‘not … very active in advocating special and differential treatment’ (Tu, Reference Tu, Zeng and Liang2013, p. 175).

More recently, some scholars argue that China even acts as a competitor to the Global South, given its economic interest has become too far apart from those of the majority of (small) developing countries. Hopewell (Reference Hopewell2022) prominently claims that in the case of agricultural negotiations, China’s insistence on maintaining high levels of domestic support is harmful to other developing countries that seek access to agricultural markets. What matters here is China’s tremendous economic growth, which allowed it to become the world’s leading provider of agricultural subsidies – estimated at $212 billion in 2016 (Footnote Ibid., p. 11). Weinhardt (Reference Weinhardt2020) also finds that, inadvertently, China’s contested claims to maintain its developing country status has undermined the principle of special and differential treatment that grants exemptions and flexibilities to developing countries.

There is, however, also a growing recognition of the ambiguous position that China finds itself in between developed and developing countries. China stands out among developing country members of the WTO because of its enormous market size, continuously high growth rates and its role in driving global growth. Despite its tremendous growth trajectory, however, developmental challenges continue to exist, especially in rural China. As a result, Bishop and Zhang’s (Reference Bishop and Zhang2020, p. 7) claim that China is caught between its roles as a developing country and a country in the transformation to a ‘developed’ one. This explains why Chinese policymakers still adhere to ‘a discourse of developmental unity’ (Bishop and Zhang, Reference Bishop and Zhang2020, p. 7) – even if it pursues ‘selfish’ interests that increasingly cut across North-South lines (Gao, Reference Gao, Toohey, Picker and Greenacre2015, p. 92). More generally, China’s emphasis on its developing country identity is not only an expression of historically grown South-South solidarity, but also considered as important to help forge and maintain relations with the Global South that forms ‘the political basis of China’s international support’ (Pu, Reference Pu2019, p. 46). These more recent assessments suggest that China’s role vis-à-vis the Global South is unlikely to easily fit the binary categories of development partner or competitor. What is missing, however, is a systematic assessment that goes beyond specific negotiating issues and contrasts China’s negotiation behaviour with perceptions of others.

III China in WTO Negotiations: Eager to Position Itself as a Development Partner

China itself has been eager to position itself as a development partner in WTO negotiations. This becomes apparent both in its political support for the development orientation of the WTO’s ongoing negotiating round as well as in the pattern of its submissions to the WTO’s Trade Negotiation Committees.

(i) China’s Political Support for the Doha Development Agenda

When Doha Development round negotiations were launched in 2001, there was a clear sentiment that development needs to be central for the WTO to succeed. The Doha Ministerial Declaration (WTO, 2001) explicitly stated that ‘[t]he majority of WTO members are developing countries. We seek to place their needs and interests at the heart of the Work Programme adopted in this Declaration’. It soon became clear, however, that the political will to deliver on this promise was rather limited. Agriculture became the major issue of the Doha Development round. Initially, China took a back seat in developing country coalitions pushing for the conclusion of a development-oriented round. For instance, at the 2003 Ministerial conference in Cancún, India and Brazil were central to the creation of the G-20 coalition that focused on agricultural negotiations. As China became more active in WTO negotiations and joined its core decision-making group in 2008 (Gao, Reference Gao, Toohey, Picker and Greenacre2015, Reference Gao and Shaffer2021), it also became more vocal in lending political support to the demands of developing countries in WTO negotiations.

China’s support for a ‘developmental orientation’ of the organisation could be witnessed prominently at the WTO’s 10th Ministerial Conference (MC10), held in December 2015 in Nairobi in Kenya. The MC10 stood out as it thought to resolve the deadlock over the continued viability of the Doha Development Agenda as a mandate for the ongoing negotiation round (Wilkinson et al., Reference Wilkinson, Hannah and Scott2016, p. 247). Major developed country members, and in particular the United States, intended to use the occasion of the MC10 to officially move beyond the Doha Development Round’s original mandate, including the Single Undertaking rule.Footnote 3 Faced with a deadlock situation since 2008, they emphasised that it was time to move on to negotiate new issues – such as e-commerce (compare Liang and Zeng, 2022, this volume) – relying on new negotiating approaches that were more flexible in excluding highly contested issues from the agenda. However, developing country members fiercely opposed this demand, as they feared that adopting a more flexible negotiating approach would effectively imply dropping those negotiating issues of particular concern to them, especially agriculture. China positioned itself as part of a developing country camp in this conflict. In a joint proposal for the conference’s final Ministerial Declaration together with Ecuador, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Venezuela, China clearly reaffirmed the original Doha mandate.Footnote 4 As acknowledged by a developed country trade official: ‘[China] has been pretty clear in all their statements that they want to complete the Doha agenda … they have been pushing hard for commitment to complete the Doha agenda. Many of us are weary of such statements’.Footnote 5 The rift between both camps was so substantial that, in a historically unprecedented way, WTO members in the end agreed to disagree.

China’s support for the Doha Development Agenda tends to reflect the importance of political ties with the Global South in Chinese foreign policy, rather than shared economic interests. China has always been keen to emphasise that it stands with the developing world, in part because close economic relations with the Global South have helped China to increase its political influence (Pu, Reference Pu2019, p. 46). Positioning China as a developing country member in WTO negotiations has thus not only been used to claim continued access to flexibilities under Special and Differential Treatment (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2021; Weinhardt, Reference Weinhardt2020), but also to consolidate support from other developing countries (compare Pu, Reference Pu2019, p. 47). Conversely, China’s decision to side with developing countries that defend the original Doha Development Round’s mandate does not necessarily reflect its own economic interests. For instance, China has in the meantime joined the WTO negotiations for an e-commerce agreement. Launching these negotiations in January 2019 while the Doha Round had not been concluded yet has been interpreted to go against the original Doha mandate (Abendin and Duan, Reference Abendin and Duan2021). Many developing countries that are less competitive than China in the e-commerce sector, for instance in Africa, had criticised the plan to launch these negotiations (Liang and Zeng, Reference Liang, Zeng, Gao, Raess and Zeng2023, this volume; SAIIA, 2021).

China’s attempts to position itself as a development partner extends beyond lending support to the development orientation of WTO talks, and includes political initiatives geared towards capacity-building in the Global South. In 2011, China, for instance, launched the Least-Developed Countries (LDCs) and Accessions Programme. It comprises several round tables, workshops, and South-South dialogue forums, as well as an internship programme for countries that seek to accede to the WTO.Footnote 6 China has, moreover, sought to support LDCs that seek to accede to the WTO informally. For instance, when the accession negotiations with Laos ran into difficulties, the Chinese chairperson of the Accession Working Group at the time, Zhang Xiangchen, was reported to have been instrumental in facilitating a mediation process.Footnote 7 Moreover, the Chinese Deputy Director-General at the time supported Laos’ accession.Footnote 8 Drawing on its own experiences of the recent accession negotiations, China has thus been eager to position itself as a development partner of LDCs. Beyond its support for LDCs, China has also put forward four proposals designed to protect and promote the interest of developing countries more generally in WTO dispute settlement (Liu, Reference Liu2014, p. 127).

(ii) Chinese Submissions to the WTO’s Trade Negotiating Committee: Siding with Developing Countries

China’s preference to portray itself as a champion of developing country concerns in the WTO also becomes apparent when analysing the pattern in its submissions to the WTO’s Trade Negotiating Committees (TNCs).Footnote 9 China prefers submissions with other developing countries, rather than with developed countries. In case of conflicting economic interests, China tends to opt for unilateral submission.

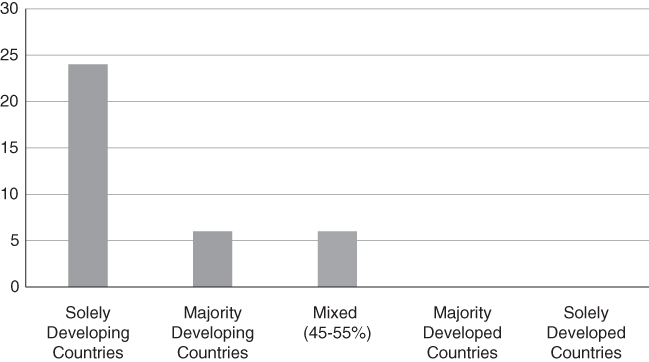

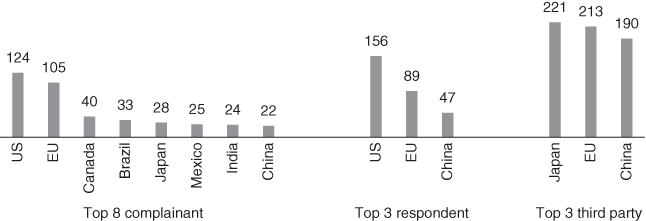

The analysis of China’s negotiating behaviour in the WTO’s TNCs reveals that if China makes joint submissions, it has a clear preference for submissions together with other developing countries (see Figure 9.1). Out of 36 submissions that China made together with other WTO members, none was made with a group comprised primarily of developed countries or comprised of developed countries only. On the contrary, 30 were submitted with other developing countries only or with groups comprising developing countries as the majority. China only rarely made submissions as part of ‘mixed’ country groups (6 submissions).

Figure 9.1 Patterns of coalition partners in Chinese submissions in the WTO Trade Negotiating Committee and its sub-groups (2001–2019)

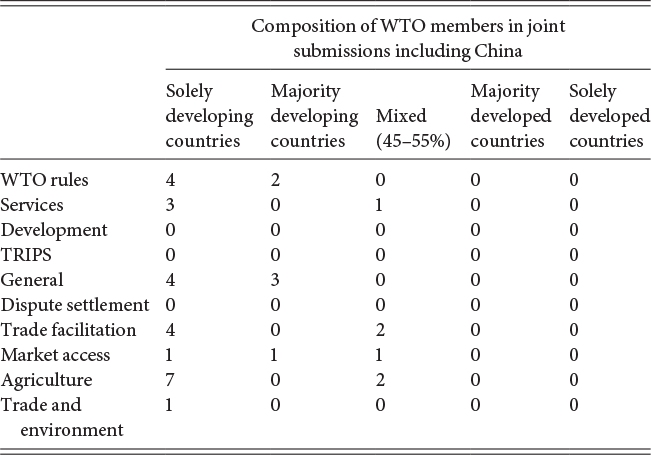

This pattern holds across all ten TNCs (see Table 9.1), and includes committees in which China’s economic interests are arguably closer to those of the developed rather than the developing world. This can be for instance seen in the market access negotiations, an area in which its offensive interests in improved market access for non-agricultural goods tend to converge with those of developed country members. However, China only made one related submission to the market access committee as part of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation coalition that includes the United States, Canada, and Japan, which reflected a shared interest in better market access for IT products. This contrasts with the behavior of other emerging economies that more frequently joined developed country members for joint submissions regarding market access for non-agricultural goods.Footnote 10

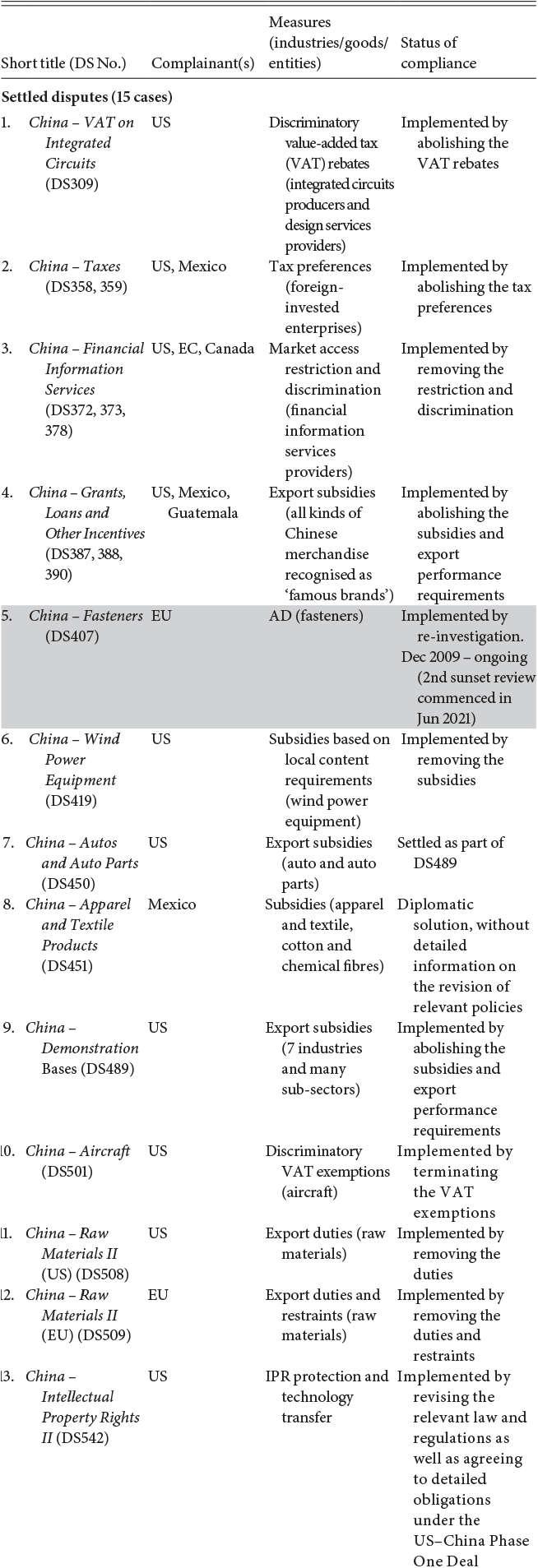

Table 9.1 Overview of China’s joint submissions in the Trade Negotiation Committee’s sub-groups (2001–2019)

| Composition of WTO members in joint submissions including China | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solely developing countries | Majority developing countries | Mixed (45–55%) | Majority developed countries | Solely developed countries | |

| WTO rules | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Services | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Development | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TRIPS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dispute settlement | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trade facilitation | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Market access | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Agriculture | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Trade and environment | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

What is notable, however, is that a considerable number of Chinese submissions to the WTO’S TNC did not include other WTO members: 34% of its submissions were unilateral, while 64% were submitted together with other countries. This suggests that China prefers to side with developing countries whenever it is able to find partners on given negotiating issues but does not shy away from defending its own interests unilaterally if necessary.

IV Perceptions of China’s Role vis-à-vis the Global South: Mixed Assessments

Despite China’s attempts to position itself as a development partner, its role vis-à-vis the Global South has become increasingly ambiguous in the past decade of WTO negotiations. Both its market size and its state-led economy set it apart from other developing country members of the WTO. In terms of its Gross Domestic Product, China has overtaken the United States as the largest economy worldwide in 2017, measured in terms of purchasing power parity. While China’s National Bureau of Statistics has been quick to point out that this does not change that China remains ‘the world’s largest developing country’ (SCMP, 2020), its rapidly increasing share in world trade puts the country in a central position in the world economy. In particular, with regard to trade in goods, China has become a leading exporter (16.1% of world exports) and the third largest importer (13.1% of world imports).Footnote 11 In contrast to many other developing countries that primarily trade raw materials, 43% of China’s global goods trade is in the more valuable category of high-value-added machines and electrical goods.Footnote 12 While this does not imply that China does not face development challenges anymore, the tremendous economic transformation of the country in a relatively short period of time sets it apart from other developing country members in the WTO.

While China clearly seeks to position itself as a development partner, its increasingly divergent economic position from other developing country members leads to mixed perceptions of its role. Trade representatives acknowledge both China’s desire to position itself as a partner of the developing world, as well as the way in which it may pursue self-interested economic motives. One representative claimed, for instance, that China is ‘devoting its attention to the development aspect of the WTO and ensuring that there is special differential treatment for developing countries in the negotiating functions of the WTO’ and that ‘they are very serious about being seen as a leader among developing countries in WTO’.Footnote 13 There was, however, also the perception that China defends its own economic interests against the Global South. For instance, regarding the Government Procurement Agreement (GPA), China was allegedly reluctant to grant preferences negotiated as part of GPA to India as a non-participating country.Footnote 14 Another trade official complained in an interview that ‘China has put its hand where its mouth is’.Footnote 15 In particular, regarding negotiations on agriculture, where China has become a major subsidiser itself, developing country officials increasingly perceive conflicts of interest.Footnote 16

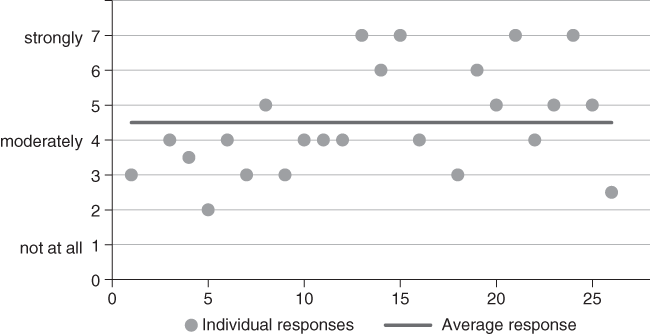

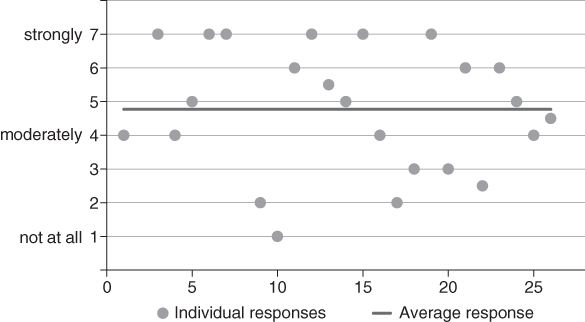

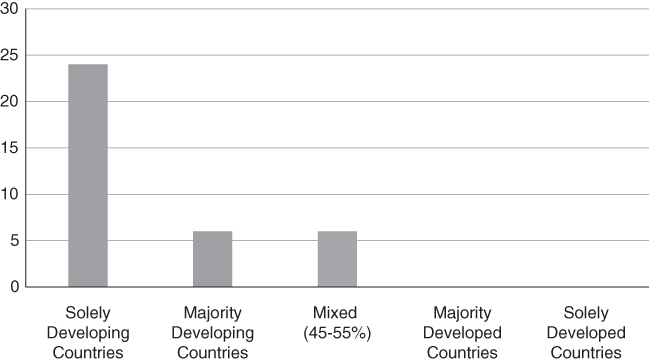

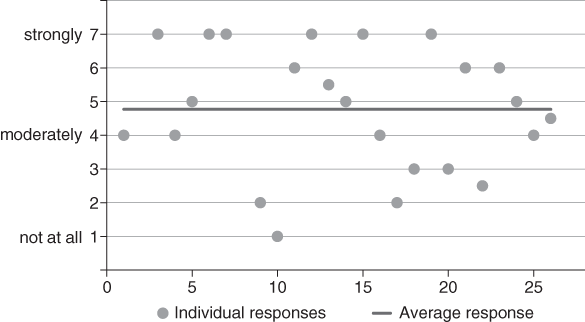

The ambiguity that exists about China’s role vis-à-vis the Global South also comes across in the result of the survey conducted among trade officials from developed and developing countries based in Geneva. When asked whether trade officials feel that China’s negotiating positions in the WTO overlap with the interests of developing countries, the average answer is 4.5 on a scale from 1 to 7, suggesting a slightly positive answer (see Figure 9.2). Yet, variation is rather strong, with answers ranging from 2 to 7. A similar pattern emerges when interviewees were asked whether they feel that Chinese negotiating positions during the Doha round were informed by historical roles that reaffirm the importance of South-South cooperation (see Figure 9.3), with answers varying from 1 to 7, and the average answer being 4.8. In these surveys, developed country representatives tended to have a slightly more favourable view of China’s role as a development partner than developing country representatives.

Figure 9.2 To what extent do you feel that China’s negotiating positions in the WTO overlap with the interests of developing countries?

Figure 9.3 To what extent do you feel that Chinese negotiating positions during the Doha round were informed by historical roles that reaffirm the importance of South-South cooperation?

While the sample size (n = 22) is too small to be representative, these findings suggest that there is no uniform perception of China’s role vis-à-vis the Global South in the WTO. Some perceive China to act in pro-Southern ways, while others remain sceptical regarding the extent to which Chinese interests overlap with those of other countries in the Global South.

Notably, developed country representatives tended to share these mixed assessments of China’s role vis-à-vis the Global South. The semi-structured interviews and the survey revealed that, on the one hand, they tended to perceive China as more clearly in line with the agenda of developing countries. On the other hand, however, some of these officials acknowledged that regarding particular negotiation outcomes, China also defends its own economic interests against the Global South. Examples included China’s tough negotiations with South Korea that were crucial for reaching an agreement on the Expansion of the Information Technology Agreement,Footnote 17 or China’s alleged reluctance to grant preferences negotiated as part of the Government Procurement Agreement to India as a non-participating country.Footnote 18 The following section further unpacks the patterns that emerge amongst those countries that China seeks to partner with on development issues – the Global South.

V Unpacking Mixed Perceptions across the Global South: The Emergence of New Conflict Lines Linked to Special and Differential Treatment

Why do some developing countries perceive China to act as a development partner, while others do not? The explanatory patterns that emerge are linked to the political agenda of S&D for developing countries in the WTO. Three main patterns emerge: First, whether or not China is seen as a partner or competitor in S&D is shaped in part by the political status that developing countries have. In particular, non-emerging developing countries tend to see China as a competitor for these special rights. Conversely, LDCs and other emerging developing country members are more likely to continue to see China as a development partner. Second, however, issue-specific conflict lines are influenced by the extent to which other developing country members share the defensive trade policy orientation of the S&D agenda. Third, political South-South ties – and variation therein – further shape perceptions of China’s role vis-à-vis developing countries within the WTO.

(i) China as a Competitor for Special and Differential Treatment: Emergent vs. Non-Emerging Developing Countries

S&D was introduced into the world trading system to counterbalance the demands for trade liberalisation with those for ‘equitable socio-economic development’ (Lichtenbaum, Reference Lichtenbaum2001, 1008). The principle grants special rights such as exemptions from liberalisation commitments or longer transition periods to developing countries, given that they are perceived to be in a disadvantaged position versus developed countries. Whether or not, and how, such a defensive S&D agenda serves the interests of developing countries in the WTO has been and remains hotly contested. Divergent viewpoints reflect different assessments of the causal link between the depths of trade liberalisation commitments and economic development (compare Low, Reference Low, Hoekman, Tu and Wand2021).

Another highly controversial aspect of S&D in the WTO is that regime members can self-declare the status they have. This creates incentives for emerging economies such as China to maintain their political status as developing countries, given the special rights that this status is associated with. For the same reason, the US and other developed countries contest China’s political status as a developing country in the WTO, given that they perceive China increasingly as an economic competitor. As a result, the status of emerging economies such as China has become a central issue of conflict and contestation in the WTO (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2020; Weinhardt, Reference Weinhardt2020; Weinhardt and Schöfer, Reference Weinhardt and Schöfer2022).

What has received less attention, however, is that other developing country members may also increasingly perceive China as a competitor. Perception is different, however, depending on whether developing countries are themselves considered to be emerging. While China’s self-declared status has been at the centre of US calls for reforming S&D, the proposed changes affect other larger developing countries as well. In 2019, the US proposed a set of criteriaFootnote 19 in the WTO General Council to define and delimit who should have access to S&D (WTO, 2019c). According to this definition, 34 self-declared developing country members of the WTO were to graduate from developing country rights. Larger developing countries that are also considered to be emerging are thus more likely to side with China, as they fear that greater differentiation would also reduce their own access to S&D. Indeed, in response to the US proposal, China, India, South Africa and Venezuela submitted a joint communication at the General Council to defend the existing system of S&D that allows all WTO members to self-declare their status as developing countries (WTO, 2019d).Footnote 20 For these countries, China acted as a development partner.

Conversely, developing country members that are not commonly considered to be emerging economically are more likely to see China (and other emerging economies) as unfair competitors for these special rights. The benefits derived from S&D may become smaller for them if they have to be shared with emerging economies such as China. One representative from the Global South for instance complained that: ‘Amongst developing countries, there is China, there is India, Brazil, but if they are allowed the sorts of flexibilities that are usually carved out for developing countries, it will put them in stronger economic position than us the developing countries who are their direct competitors in the market’ (quoted in Weinhardt, Reference Weinhardt2020, p. 405). This concern was shared by other representatives from non-emerging countries in the Global South,Footnote 21 with one official claiming that among the negotiation group comprised entirely of developing countries that he was working for, there is ‘the sentiment that they do the competition with them [emerging economies such as China] for S&D but are not at the same level of development’.Footnote 22

Lastly, China’s support for S&D in its negotiation positions is least controversial when it seeks to strengthen these special rights for the narrow group of LDCs – rather than for itself.Footnote 23 An example is China’s support for the LDC countries’ repeated requests for a prolongation of the TRIPS waiver, which developed countries tended to question. Here, flexibilities are reserved for a clearly defined and narrow group of WTO members – which excludes most developing countries, and most certainly those that are emerging economies.Footnote 24 Evidence from the semi-structured interviews suggests that LDC representatives also assess China’s political support within the WTO positively. One representative, for instance, mentioned that China urges other developed countries to be more flexible when LDCs negotiate accession to the WTO compared to other countries.Footnote 25 The trade official also positively referred to the South-South Dialogue on LDCs and development than China initiated, and that China is granting duty-free and quota-free market access to all LDCs.Footnote 26 This indicates that China most unambiguously acts and is perceived as a development partner in negotiating issues where its distinct economic size is less pertinent, such as support for LDCs.

(ii) Issue-Specific Conflict Lines: Defensive or Offensive Trade Policy Orientation?

Perceptions of China’s role are, however, not only shaped by the political status of countries from the Global South. Issue-specific conflict lines are central in shaping whether or not China is perceived as a development partner. Given the inherently defensive nature of the S&D agenda on development, developing countries that pursue a liberal, and more offensive, trade policy orientation are more likely to see China as a competitor rather than a development partner. Notably, these conflict lines can vary across negotiating issues, and partly cut across the political conflict lines (see Section V(i)).