Even though industrial meat provision can seem simple in all its efficiency, this was not the case in Copenhagen in the final decades of the nineteenth century. If we broaden the perspective of meat and the consumption entangled with it also to involve an export market, a network of buildings and infrastructures, and emerging concerns about health and hygiene, we can see how meat in a sense produces and transforms urban space in the period. This article will argue that industrialization led to a reassembly of these different components, forming a structure that changed urban space in the modern city. In what ways did urban space and the provision of meat affect each other in the years around the turn of the twentieth century? In order to investigate this question, the article will focus on events and practices involved with the provision of meat in Copenhagen around 1900. The centre of attention will be the so-called Meat City, the first major slaughterhouse facility in the city. While never becoming formalized, the name ‘Meat City’ spread from popular custom among Copenhageners to be the common reference in the press and informal documents of the municipality.

I will begin by sketching the way in which the production, distribution and consumption of meat became industrialized in Denmark and especially in Copenhagen during the late nineteenth century. This overview will point to the new ‘meat node’, the public slaughterhouse, and the changes it brought about in the occupations related to meat. This will lead to a study of the change in hygienic paradigms, which gradually gained an important role in the city. Another perspective is the public focus on the killing of animals on an industrial scale, and this will be discussed as part of the ‘spacing’ caused by meat provision. These steps should outline the components of the provision of meat that are relevant for the final argument, which is that it was precisely the contradictions implicit in the industrial provision of meat that caused it to be such a force in the social and cultural change of Copenhagen of the period in question. The overall approach in viewing these changes is to identify them as spatial phenomena.

In the Stomach

Visitors to mid-nineteenth-century Copenhagen coming from the west would first reach the Valby Bakke hill. From there would emerge the view of the butcher stalls, erected along the old country road leading towards the city's Western Gate.Footnote 1 Later, the road became a bustling artery for city traffic, but the butchers remained there, proudly displaying butchered pigs from their facades (Figure 1). Upon entering the city gate further ahead, the first sight would be the Hay Market, where food for the city's animals (cattle as well as horses) was sold.Footnote 2 If one continued straight on, one would reach Gammeltorv (Old Square) and Nytorv (New Square), where animals were brought for slaughter and sale. On New Square, butchers would be by their carts, killing and cutting up pigs and oxen in the middle of the square. Further on, a street leading north had been called the Meat Trading Street ever since medieval times, owing to its primary function.

Figure 1: Butcher at Vesterbrogade, 1870s. The Royal Library, Copenhagen.

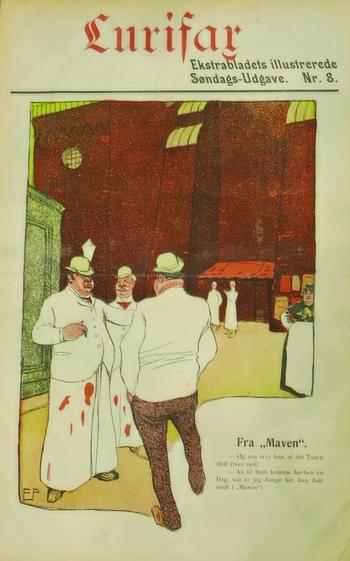

From here, a small alley led into the heart of the medieval city, to the old Nikolaj Church Square, where rows of identical butchers’ stalls formed the core of the space. Financed by the municipality, these stalls displayed their products in an actual wall of first-class meat. At the back of the stalls, forming an inner yard, one would be surrounded by intestines, blood and bones. Here, the cheap cuts were sold. Copenhageners called it the Stomach (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Drawing, Erik Petersen, Ekstrabladet, 1906. The State Library, Aarhus.

Concentrating the provision

As described above, until the mid-nineteenth century the city of Copenhagen was pervaded by meat. Animals were fed, slaughtered, cut up and sold in public, while animal offal and blood was an everyday sight for residents and visitors alike. This closeness between slaughter and everyday life can be traced in many sources, which also reveals that it was not always pleasant. For instance, in 1807 there were medical concerns that: ‘Emanations from much blood, from the content of the intestines and from the freshly slaughtered meat, quickly contaminate the air; the running water and blood spreads the stench rapidly over the whole town and leads it into the canals.’Footnote 3 In addition to meat production within the city walls, an even greater amount of meat was brought to marketplaces and squares from the hinterland. In Copenhagen during the early nineteenth century, there were two market days a week, and local peasants would populate the town's four to five designated squares in these weekly rhythms, concentrated in its medieval core. Urban feeding goes deep into the workings of the large city, even deep enough actually to define a city, as Hohenberg and Lees have argued.Footnote 4 The moving of animals, dead or alive, in and between cities has been a significant aspect of urban life in the country from the medieval period, and since the meat trade privileges of the Danish nobility were lifted in 1799, the enterprise and networks of cattle routes providing the Danish markets and towns with meat has been an important part of the urban and national economy.Footnote 5

However, during the second half of the nineteenth century the provision of meat in towns and cities changed radically. The consumption of meat in Denmark, and in most western countries, increased to unprecedented levels, and at a speed which was not replicated until well after World War II.Footnote 6 At the same time, all the activities relating to slaughtering and butchering were centralized in the major cities by municipal and, around 1900, state regulation. These two developments were intertwined with the industrialization of meat production and provision, something which also developed rapidly during these years.Footnote 7

Given the dynamics of Danish industrialization, city and countryside were more intertwined than in other parts of western Europe and North America, and meat production serves as a good example of this entanglement. Denmark was also a bit late in terms of developing an industrial workforce: it was not until after World War II that the number of industrial workers exceeded that of agricultural labourers, and around 1900 the two sectors were entangled in a tight interdependency.Footnote 8 The adaption of agriculture to animal production caused an expansion and a demand for production machinery from the urban factories, for example – we shall return to this below. During the period 1880–1914, the rise in industrial production was closely related to a similar expansion in the agricultural sector, owing to new strategies of production and organization in both sectors as well as interdependence.Footnote 9 Thousands of animals were brought into the ‘meat nodes’ of the major Danish cities like Copenhagen, Aarhus and Odense by railway to be sold or slaughtered and moved away again into urban consumption or export by ship. A number of technologies and innovations such as cutting lines, cooling facilities and new architectural designs accelerated the pace at which this movement happened, with the development of refrigeration being an important turning point in the distribution and movement of meat.Footnote 10

In the late 1880s, as noted above, the municipality of Copenhagen took steps to centralize the provision of meat in one large facility, later to be named as the Meat Stock Exchange, or simply the Meat City.Footnote 11 Designed as a hub from the beginning, the Meat City was established close to the enlarged Copenhagen harbour and connected to the expanding rail network as well as the important road coming in from the west, which connected Copenhagen (located in the far east of Denmark) to the rest of the country. Developing into a large building complex covering slaughter halls, market buildings, laboratories and related industries, this city-in-the-city also had its own rail track, gates and walls. One striking feature of the building complex – the largest municipal project of the time alongside the sewer and tram systems – was the material and visual borders it produced. On the one hand, the building layout employed emergent techniques of transparency, including large open halls, broad asphalt roads, large window frames and open ramps in reinforced concrete.Footnote 12 This shows the transferral of slaughtering from the traditional, enclosed ‘butcher's cell’ of the Parisian artisanal type to large slaughter halls, which could be monitored easily by the authorities and were easily accessible for cleaning as well as being equipped with transport systems such as the meat cutting line. On the other hand, the whole complex was kept out of sight of the urban public, walled and enclosed as it was, with control points and integrated lodgings for travelling cattle traders, so they would not have to leave the premises while doing business.Footnote 13 Figures 3 and 4 show the expansion of the complex over 10 years, from 1879 to 1889. The earliest site comprised the central cattle market halls with stables along both sides, and in the southern end a dining hall along with a horse market. From 1883, three slaughtering halls were built (to the eastern side on Figure 4), which meant that the municipality could effectively prohibit private slaughtering in the city. Then came the larger buildings, for example the Monumental Oxen Hall built in 1901, the railway infrastructure and the cooling facilities that can be seen far north on the map.

Figures 3 and 4: Ground plans of the Meat City 1879 and 1889. Copenhagen City Museum.

Figure 5: Meat consumption, Denmark 1800–1914.

Contradictory forces were also at play in terms of access. The Meat City was designed to be easily accessible, transparent and legible, as was the emergent factory architecture of the period. Figure 4 illustrates the direct access that carts (through the gate to the south), trains and ships (from the north, top end of the map) had to the inner parts of the complex. On the other hand, a degree of control and systematic isolation was at work to a degree hitherto unseen in the city. Gate control, quarantine systems, laboratories and commissionaires strove to provide a constant and, at least in principle, omnipotent gaze.Footnote 14

The provision of meat to the urban population gained a new layer of control with the Act on Domestic Meat Control of 1906. Here, standards were stipulated for each municipality, stating, for example, that all meat should be identified in three quality categories and stamped as such. State legislation was a sign of the rising importance of meat, partly because the export of Danish food products changed rapidly in the 1880s and onwards. On a broad scale, meat became a central catalyst, or a site for the above-mentioned ‘entangled’ industrialization of Denmark, with agriculture and industry developing in a reciprocal and intertwined way in the decades preceding 1900. The basic elements were as follows. In the period 1870–90, the agricultural sector in Denmark was radically reorganized following challenges on the international market for grain.Footnote 15 Danish peasants had turned from grain to animal production as a response to low American grain prices, and to the two products that became cornerstones of modern Danish exports: bacon and butter. Furthermore, Denmark had traditionally sold meat in Germany, but following German protectionist import restrictions, Danish farmers in the 1890s turned to Britain, where they found a virtually insatiable market.Footnote 16 Correspondence from the period shows vividly how agricultural organizations were amazed at the volume of the British market for Danish animal products, especially bacon, which became a phenomenon in itself in Britain, with significant and ambivalent influence on the modern British diet.Footnote 17 By 1900, practically all Danish bacon was exported to Britain, and the Danish market share of bacon in the country was around 50 per cent.Footnote 18 These factors, and the Danish ability to produce good quality meat quickly, caused the characteristic production of the farm to intertwine with that of the factory, mutating into an agro-industrial pattern. New infrastructures emerged for moving livestock, whether dead or alive, and the economic outcome caused spillovers in urban machine manufacturing. This was especially the case for the national and regional capitals of Denmark, Copenhagen, Aarhus and Odense.Footnote 19

This entanglement was strengthened by the Danish co-operative movement, for which slaughtering became the second largest activity after dairy production. The co-operative slaughterhouses became an influential interest group and also a central agent of technological, organizational and economic change in the provision of meat products in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 20 They played a central role in Danish exports, using the experience of centralization and regulation that was developing in the cities around 1900, and working together with the Danish state and private slaughter enterprises to create a strong brand of Danish bacon.Footnote 21 At the same time, the Danish capital was regarded as a progressive model in international scientific publications such as The Lancet, and this was linked to the emergence of co-operative practices of slaughtering and management.Footnote 22

From 1883 onwards, a number of co-operatives, owned collectively by local farmers, emerged in the Danish countryside, which established dairies, electrical works, cooling houses and other small-scale industrial plants in order to supply local communities. Soon after 1900, more than 40 such plants were functional around the country.Footnote 23 At the outset of World War I, 43 co-operative slaughterhouses had been established in Danish cities, taking part in the export adventure, and thriving on the recent discovery that skimmed milk from the growing dairy sector was a good source of food for pigs.Footnote 24 The co-operative slaughterhouse became iconic in the narrative of Danish agricultural progress, as evident from a contemporary observation by the Danish smallholder and writer Johan Skjoldborg, whose protagonist in the novel The Crowhouse regards the local slaughterhouse as the promise of a great future.Footnote 25 Together with the rise of private export slaughterhouses, the co-operative meat industry was one of the reasons for the importance of meat in the merging of city and country around 1900.Footnote 26

During industrialization, practices of slaughtering became separated from those of butchering and retailing meat. The turn of the twentieth century, as economic historian Jørgen Fink points out, heralded a radical change for the Danish butcher as a craftsman.Footnote 27 Whereas the retail butcher remained attached to the culture of master and apprentice belonging to the same household, the wholesale slaughterer became an industrial worker.Footnote 28 Moreover, while the retail butcher developed a new, ‘clean’ way of displaying meat in his shop for public gaze, the wholesale butcher worked in the ‘dirty’ slaughter hall, removed from the eyes of the public, but regulated by public authority.Footnote 29

Connected to this division of meat labour, a multiplicity of other trades and professions became involved in the provision of meat.Footnote 30 One of these trades was the market for meat by-products such as offal, intestines and hides. This became an emergent industry of its own, spatially and economically connected to the Meat City, producing bone meal, tallow and tanning leather, amongst other products. The commissionaires were also involved, combining the role of the traditional cattle trader with a new practice of value fixing in the changing meat market. There were also veterinarians, who were expected to deal with the important area of animal hygiene. There were engineers who specialized in the development of ‘meat technologies’ such as slaughter tools, meat circulation, refrigeration and the calculation of risks and outputs, private or municipal. Specialized officials also emerged, building systems around the regulation of the relations between the meat market, city and state, and police officers from the new Veterinary Police, later called the Health Police, handling quarantines and sanctioning the regulatory system. As in other fields of industrial production, the meat industry also provided work for women, specifically on the poultry lines.Footnote 31

Consumption curves

In the second half of the nineteenth century, we witness a rise in Danish demand for meat, not unlike other large western cities, where consumption increased, with urban populations becoming the largest meat eaters.Footnote 32 Recent research shows that pork exceeded beef as the most consumed meat product in Denmark shortly before 1900, and that poultry consumption was also increasing.Footnote 33 The urban population, in general, and the growing middle class, in particular, began to demand fresh meat.Footnote 34 For the working-class population, the growing meat diet also took the form of industrial products like liver pate and sausage on mass-produced bread, and processed meat, all products made from the surplus of meat and intestines not fit for export. A diet of ‘leftover meat’, which became dominant later in the twentieth century, had made its entrance into Denmark.Footnote 35 The transformation of the meat economy led to an expansion in production and lower prices, which made fresh meat accessible to a larger part of the urban population, especially in the capital.Footnote 36 In the years around 1900, between 150,000 and 200,000 animals were slaughtered each year in Copenhagen.Footnote 37 Many more were brought into the city in order to be shipped out again alive, mainly to Britain. The long tradition of driving cattle along trails going back to the medieval period was effectively erased with the advent of the railway, which transformed land transportation, and steamships facilitated the movement of cattle over sea as well.Footnote 38 The consumption of meat was also encouraged by hygienic authorities at the time such as the doctor Chr. Jürgensen, the first Nordic physician to connect biochemistry and nutrition.Footnote 39 Together with other prominent figures such as the pathologist Peter Panum, Jürgensen recommended meat as the central source of protein for the working class, a piece of advice that, though contested, found its way into public regulation.Footnote 40

Floating between two worlds

Simultaneous to the processes described above, multiple practices, spaces and technologies were developed to make the killing and dismembering of animals as smooth, silent and isolated as possible. This process was investigated by ethnographer Noëlie Vialles, who, in her account of contemporary slaughtering practices, suggested that one of the most vital features of modern slaughter was the distinction between those who killed the animal and those who ate the meat.Footnote 41 This differentiation was deeply embedded in the design of the modern slaughterhouse. Ordered as a directional space, it was divided into a clean and an unclean sector, leading through a space of passage, which Vialles described as ‘floating between two worlds’ of the living animal and the dead meat.Footnote 42 The act of killing was itself split into several steps, emphasizing this floating process: first, the cow was caught in ‘the trap’, singled out from the flock, then rendered unconscious with a stunning device. In a way, the stunner introduced the state of not being alive for the animal, while the act of making the animal bleed made death irreversible. In between the two, Vialles suggested, the act of killing was blurred, opening the possibility of ignorance about who actually caused death. This, Vialles found mirrored in the French term for slaughterhouse, ‘abattoir’, meaning a place for ‘bringing down what is standing’. When the animal fell, it was but a body, ready to become a carcass. Vialles’ description of the contemporary meat industry fitted well with procedures of slaughterhouse work around 1900. Here, too, the animal was sedated by means of clubs or similar tools, then lifted by its hind legs. Its throat was cut and the body was positioned so a maximum of blood could run off, transforming the silent body into a carcass. It was then flayed while hanging from the ceiling, and the body parts – from now on referred to as ‘the cuts’ – were removed from it, turning it into a dismembered set of bones and muscles. Thus, the industrial division of labour divided traditional slaughter practice into multiple small steps, expanding and almost stretching the floating passage between living animal and dead meat. What was previously done by one or two men was now divided into the labour of a dozen workers along the ‘disassembly line’.Footnote 43

Much of Danish industry involved producing perishable goods. Beside bacon and butter, other products such as bread, beer and cheese became well known during the twentieth century for their high standard and reasonable price. The success had a number of causes. New technological innovation was part of it, as was also a decentralized organization. But a central agent of change and growth in the mass production of perishable food products was the new, applied chemical and biological sciences. The most famous Danish industrialist to incorporate a more rigorously scientific approach to production was the founder of Carlsberg breweries, Carl Jacobsen, who observed and studied the latest developments achieved by leading researchers such as Louis Pasteur. Using Danish barley and its own yeast recipe, the Copenhagen based brewery was able to develop and control the complex fermentation processes, enabling it to produce a standard product. Other industries also based in the capital, such as the rye bread factories of Schulstad and the co-operative dairy Enigheden (‘The Unity’) also based their production on certain types of fermentation processes, exploiting the knowledge of a growing group of chemical engineers across Europe.Footnote 44 For these industrialists, the key to success was the control of decaying processes. With meat, however, this was more problematic.Footnote 45 Earlier habits of hanging meat until it became tender never gained ground in industrial processing, but remained grounded in older meat production realms such as game or manual butchery. One explanation could be that the fermenting processes used for meat were unfit for industrial processes, but it is more likely that the desire for fresh meat and anxiety concerning contagion simply reduced the demand.

In the words of Vialles, meat became ‘de-animalized’, then. While becoming a mass commodity, meat was taken as far as possible from its original relation to the animal body and given an abstract materiality, prepared to enter the human body.Footnote 46 A widespread notion in food sociology and food anthropology views meat as simultaneously the most highly prioritized and contested element of modern western food culture. This double position is related to the basic ambivalence of meat as a costly, desirable and ethically problematic food.Footnote 47 One element of this has emerged from the shifting relationship with animals in modern urban life, from domestic livestock to ‘walking meat’, removed from the eyesight of modern urbanites.Footnote 48

Decay, contagion and modern sensitivity

In the slaughterhouse, certain processes needed to be eradicated or controlled, notably contagion, contamination and the decay of meat. Interestingly enough, decaying meat in itself was not necessarily regarded as a health hazard, as recognized in contemporary popular scientific literature: ‘The simple decay of meat seldom gives rise to serious poisoning. Game is enjoyed by some in more or less decayed condition, and the “corpse poisons” (Ptomaines) are destroyed by heating the meat.’Footnote 49 Even so, decaying processes were becoming an object of anxious attention in Copenhagen, as in most other large, industrial cities in the second half of the nineteenth century. In its basic, chemical sense, fermentation involves the conversion of carbohydrates into alcohols and carbon dioxide or organic acids using yeasts or bacteria under anaerobic conditions. The result is a multiplicity of transformative processes, different in each case: hard can become soft, dry can become wet and sustaining structures can dissolve, leaving behind a transformed material which often provides ecosystems for bacteria, worms, insects and larger animals. As well as being a productive process, ‘decomposition’, as it is properly known, is also the way most food products are transformed into inedible, disgusting and unhealthy objects. In short, it is part of decay. As the quote above indicates, partly decayed meat was considered a delicacy in the early modern city. But while the delicate taste of controlled decay became part of many other products, meat in this period was supposed to be as fresh as possible. At the turn of the century, rotten pork or beef was regarded as one of the most repulsive and dangerous objects of the modern city, and any attempt to accept decay in the slaughterhouse would be deemed inappropriate by public opinion.Footnote 50

The microbic invasion

The anxiety concerning decaying meat related to a new hygienic sensibility, partly driven by the rise of medical and biological sciences and strengthened by the urban epidemics of the time. In particular, the large outbreaks of cholera, which arrived in Copenhagen in 1853, mobilized groups of hygienic reformers among the urban bourgeoisie.Footnote 51 The success of this movement brought about major investments in sewer systems and water supplies in most western cities along with the establishment of prominent public institutions and municipal departments dedicated to managing health policies and inspecting standards of hygiene. A well-known example in the Danish historiography is the development of the Copenhagen City Engineer's Office 1886–1912 under Charles Ambt, an engineer-entrepreneur who constructed central networks such as the sewer system of 1906.Footnote 52

Among these institutions was the Public Meat Control system in Copenhagen. Through the Municipal Health Act of 1886, and following procedures for slaughterhouse control adopted in 1887, a system was established by the national parliament for ensuring veterinary control covering the whole meat distribution system, that is, the Meat City as well as all the butcher's shops in Copenhagen. The regulation specified in particular that any person entering had to be registered, children under the age of 14 were prohibited from entry and no animal or animal part could leave the facility without a proper stamp. Specially trained officials and police officers tested all the livestock and meat as it moved through the system, while laboratory personnel acted as the microscopic eyes of the control organization.Footnote 53 For example, we get a glimpse of the spatial layout through a description of the trichinosis test facility of 1910: ‘[the facility has] 3 halls, a laboratory, a veterinary room, a lunch room and 2 toilets. . .[the personnel consists of] 2 registrars, 8 test cutters and 70 trichinosis searchers’.Footnote 54 Women were chosen for the jobs, since they were considered best at maintaining their visual concentration on small details, and they were only allowed to work for eight consecutive hours so they could keep this level of visual focus.

The system was pervasive. In 1889, for instance, 40 tons of beef alone were discarded, and health police officers carried out more than 37,000 inspections of shops and butchers in town.Footnote 55 The municipal inspectors at the slaughterhouse gates were veterinarians, and through them the available medical and biological knowledge was applied on an industrial scale. Their logbooks confirm that the animals were entered as bodies or body parts, for example, ‘a body of 1 calf’, or ‘head and legs of 2 pigs’. These bodies were accepted or discarded due to observed symptoms, which paints the impression of a system that was anxious to rule out anything suspicious, whether unhealthy or not.Footnote 56

Another example of this suspicion can be found in the ‘meat scandal’ that caught public attention in the city in 1890. In February, the newspaper Politiken reported that a deal had been agreed between the city's master butchers and the mayor. Before compulsory slaughtering, the butchers could keep their own livestock for private sale. The business model was to feed the offal – typically intestines and residual meat – to their stock of pigs, thereby recycling such products and contributing to their profits. This practice became illegal, and the butchers complained to the city council. At a meeting between the two parties, Mayor Borup advised the butchers to take a closer look at the large amount of offal produced by the slaughterhouse that was now processing all animals from the Copenhagen hinterland. The butchers did not hesitate long before establishing a co-operative pork facility on the outskirts of town, feeding on the remains from the public slaughtering. Thus, the stream of intestines, bones and residual meat from the Brown Meat City provided a great energy source for feeding other hogs for slaughter, a re-use cycle that was formerly part of the butchers’ own household, but was now managed on an industrial scale.

Handling offal from a facility as large as the public slaughterhouse was no simple task, however. Industrial meat processing had complex consequences, and livestock from one farm could end up as food in hundreds of different homes. Animals were literally split into fragments of body parts, some shipped off in bundles, others sold to butchers in town, while some became food for other animals which were subsequently recycled in a similar fashion. If a disease broke out at one farm and was not identified, it would spread at unprecedented speed.

At the gates of the slaughterhouse, all livestock was tested in order to separate good from bad meat. However, as the animal body was dismembered, it became hard to maintain control: body parts circulated at a fast pace around the Meat City, which was the size of several football stadiums. This constituted both an opportunity and a problem for the butchers involved. The deal with the municipality was that the butchers would handle all the offal and in return get it for free. However, the spatial logistics involved in the new industrialized practice were relatively complex, involving different slaughter halls, quarantine halls, laboratories and so on, which created multiple points where good and bad meat could be mixed up. This was a challenge to the people who were responsible for handling the ‘meat out of place’ – the butchers – but it also tempted them to exploit this labyrinthine system for their own interest, which was exactly what they were accused of.

In October 1890, people began to wash their hands of the case. A letter to the editor of Politiken signed ‘Y’, which was probably written by a veterinarian, stated that the vets had no responsibility for slaughterhouse sanitation since they had no business there. Thus, when contaminated and healthy meat were mixed at this facility, it was only supervised by the master butcher, in this case a certain Mr Ulrichs. The correspondent commented, ‘The fact that the administration leaves so much authority with Mr Ulrichs surprises the vets, but they have no say in this.’Footnote 57 Furthermore, ‘Y’ suggested that in order to keep track of the contaminated meat, it was not sufficient to provide the animal in question with a slip, since, for example, all the intestines could be removed and circulated as healthy meat. Instead, ‘Y’ proposed that the meat should be weighed to determine if any meat had been removed, with a view to ensuring that no discarded meat was sold. And the letter went on to say: ‘One has almost no guarantee [of the meat quality]. . .there are only a few stamps on each animal, so piles of meat can be sold without a stamp. . .is it not a little uncanny. . .? One suspects that the ugly, black spots are meticulously cut from the meat.’Footnote 58 The letter ended with a suggestion that the German Freibank system be adopted, under which different qualities could be sold from separate localities in the slaughterhouse area of the city. It was impossible to distinguish good from bad meat just by eyesight, and now, through the attention generated by the scandal, it became apparent that the measures taken to identify circulating steaks and shanks were not working. The microbes were circulating freely between animal and human bodies.

The veterinarians and others with veterinary training, such as the trichinae searchers, were ultimately responsible for the safety of the animals and the meat that would be sold for human consumption. But the vets’ role as ‘safety officials’ implied a mediation of knowledge that was subject to change at this period. Until the 1880s, the dominant framework for understanding the spread of disease, in Copenhagen especially, had been the idea of the miasma, thriving in swamps, still water, air or in rotting material.

This changed relatively quickly with the discoveries of biologists such as Robert Koch and Rudolf Virchow, and with the hygienic movement in France and, in particular, Louis Pasteur.Footnote 59 With the new theories of the cell, the microbe and the revival of contagion from living organisms, the body emerged as a somewhat different entity. The borders between human and animal bodies as organisms were now unstable and fragile. First, Virchow's cell theory made it probable that bodies were not wholes, but assemblies of millions of small, independent bodies, made up local zones of bodily tissue, whose condition determined the life or death of the body, human or animal, that they sustained.Footnote 60 With Robert Koch's theory of microbes travelling from body to body, this assembly – the human or animal body – became framed as an environment which provided habitats for a good many other living organisms, some of which were unhealthy for the hosting body, or simply killed it. The human and animal body in this period surfaced as permeable and fragile, unable to defend itself against the attacks from invisible hordes of invading life forms. The microorganisms that Koch and others had seen in their microscopes could transgress the skin, body openings, eyes or other entry points, and enter the tissue, intestines or veins to exploit the potential for feeding and multiplying, thereby consolidating their invasion.

The field of bacteriology was still relatively new before World War I. The new body became appropriated by the notions applied to Koch and Pasteur, and through these notions it was tied to the tension between the visible and the invisible. As Laura Otis notes, Koch ‘had identified the disease-causing agents by rendering them visible. He could eliminate diseases only if people themselves were equally available to his gaze.’Footnote 61 And Bruno Latour has a central remark on the same theme of a visual warfare concerning Pasteur. As he notes, the followers of Pasteur were ‘Like the first observation balloons. They made the enemy visible. Without replacing the armies, the battles, or even the commanding officers, they indicated or directed the blows.’Footnote 62 In this language of war, visibility and bordering shows the degree to which the body was becoming a space to be protected, but at this specific period the enemy was only partly visible.

The focus on contagion and health had a variety of consequences. Since the slaughterhouse was a node for the distribution of meat not only on a national but also on an international scale, the state was concerned. From the 1870s onwards, there was close contact between urban and state agents concerning these matters, notably the Ministry of Interior, the Royal Veterinary School, the city police director and regional administrators.Footnote 63 At first, regulations were discussed to control the animals shipped into the city harbour that were at risk of carrying contagion. Shipping companies had to load the animals into temporary stables at the harbour for examination by veterinarians, after which they were taken to the slaughterhouse under the escort of police officers.Footnote 64 This quarantine space was the object of long discussions and was refined and developed in the first years of the twentieth century. Floors and cribs were made of concrete, walls were covered with glass and all cracks and joints were covered with pitch. In 1902, from January to October, 2,398 animals were inspected at this location.Footnote 65 The animals deemed to be dangerous were burned in a destruction facility built in 1890 at the Meat City.Footnote 66 Temporary stables were also set up in Istedgade, a street close to the Meat City, and routes were established for the police-escorted cattle to move between the different localities.Footnote 67 The enclosed and regulated slaughterhouse subsequently expanded and established quarantine points around the city, in an effort to keep up with the moving bacteria. This effort involved the state, the city and the local slaughterhouse officials, and was under keen public surveillance as demonstrated by the meat scandal case.

Conclusion

With the slow build-up of the Brown Meat City in Copenhagen, it is possible to identify a spatial complex embodying the contradiction of modern urban meat provision: on the one hand, the consumption of meat, and especially pork, rose steeply to a new level in this period. The short version of the story is that the growing Danish urban population became meat eaters to an unprecedented degree, with the citizens of the major cities the main meat eaters.Footnote 68 On the other hand, meat was being removed from the public eye, in a rapid acceleration of a development that had begun centuries before.Footnote 69 With slaughterhouses in large cities beginning from the seventeenth century, the most comprehensive public project was the abattoirs of Napoleonic Paris. Even back in those days there was some focus on the hiding and erasing of the killing, butchering and bleeding processes that transform the living animal into dead meat.Footnote 70 In early nineteenth-century Copenhagen, however, living animals and dead meat remained visible features of everyday urban life. Then, over a relatively short period of time, during the second half of the century, the city became cleansed of animals, living and dead, until they returned later as pets. In this way, as explained by Bulliet, a change occurred in the human–animal relationship from a domestic to a ‘post-domestic’ culture.Footnote 71 Around the turn of the twentieth century, animals became the centre of attention as a commodity, but the production connected to this commodification had to be isolated from human bodies and the public eye.Footnote 72

For social historian Amy Fitzgerald, post-domesticity and the contradictory relationship between the urban dweller and animal-as-meat are what define a ‘modern sensibility’.Footnote 73 The concept, broad as it is, captures something about why we should look at meat in the first place as a key phenomenon of urban modernity. The almost obsessive surveillance of shops, dead meat and quarantine spaces suggests an anxiety connected to both the discovery of the bacterial universe, but also to the contradictory presence of a rising desire for fresh meat and simultaneously an expanding repulsion in the face of everything caused by this desire – slaughtering, cutting up, examining meat and so on.

Along with this, which was partly caused by the rise in Danish meat exports, from 1888 onwards it was compulsory to slaughter animals in public slaughterhouses, or abattoirs. Due to the need for infrastructure to carry both livestock in and dead meat out, the slaughter facilities had to be situated near road and rail junctions, harbours and later electrical plants, all of which acted as the nodes around which industrial cities grew. The expanding business and consumption of meat thereby created an explosion in livestock being brought into cities from the surrounding farmlands, which was concentrated in the heart of the cities, but where animals were slaughtered out of public sight.