He spoke very well, but he spoke the language of the people. And the people flocked in when his name was announced for a rally or for a conference.Footnote 1

INTRODUCTION

In the twenty years between 1890–1911, Pietro Gori was one of the most famous anarchists in Italy and abroad and, long after his death, he continued to be a key figure in the socialist and labour movement of his native country. Like other members of the Italian anarchist movement, above all his friend Errico Malatesta, Gori spent part of the last decade of the nineteenth century abroad, away from the repressive policies enforced in Italy. His long exile between 1894 and 1902 – briefly interrupted between 1896 and 1898 – was at the root of his extraordinary prestige, especially in the United States and Argentina. His stay in the US (1895–1896) established him as one of the most beloved radical leaders in the Italian immigrant communities.Footnote 2 During his long residence in Latin America, he became a charismatic player in Argentinian anarchism and in the burgeoning labour movement (1898–1901).Footnote 3

The importance of Gori’s leadership, as well as that of other socialist and anarchist figures of the period, has been underestimated. In the studies on the different forms of socialism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the subject of leadership – and especially charismatic leadership – has long been neglected or sidelined from the field of interest of historians. After World War II, Marxist approaches and the perspectives inspired by the Annales led to inadequate attention being paid to the subject of leadership in the political movements of the late nineteenth century. Studies focused largely on the circumstances in which movements and parties are born and develop, the earliest forms of organization, their functioning, practices, and the collective actions of the participants, as well as popular imaginaries and desires.

With the cultural turn that has also begun to influence political historiography, the “great figures” have returned to the centre of several lines of research. Nonetheless, the reinterpretation of the socialist and anarchist world of the late nineteenth century and its exceptional figures has been fairly limited. Indeed, over the past twenty years, it is the research on nationalist movements and on the processes of mobilization and socialization conceived and deployed by the ruling elites that has become increasingly important in studies on mass politics. In short, nationalism and its “heroes” and the nationalization of the masses by the ruling classes of the late nineteenth century have become the focal point of a large number of works devoted to this period of history.Footnote 4

While the literature on the nation and its “architects” is systematic, the dynamics of change in the study of the political traditions tied to the history of the labour movement are not quite so strong. The transformations associated with the cultural turn are of a less organic nature. The widespread approach among scholars of interpreting these traditions in terms of secular religions has resulted in analyses that focus primarily on symbols and the collective rituals of socialisms.Footnote 5 Although a small amount of space has been given to “great figures”, there remains a prevailing interest in the aspects relating to the later construction of their cult by the parties and their members attempting to consolidate group identities and political structures.Footnote 6

Several key studies have been conducted, but a thorough and comparative perspective on leadership – particularly in relation to the category of the charismatic – only started to develop in the past fifteen years, as research groups have begun to address the historiographical gaps by taking into account Weber’s categories and by exploring some case studies.Footnote 7 In particular, the edited volume Leadership and Social Movements (2001) was one of the first systematic attempts to take stock of existing literature, reinterpret the German sociologist, and analyse several cases.Footnote 8 While focusing heavily on the twentieth century, the volume provided major methodological insights that were partly adopted by a recent collective work entitled Charismatic Leadership and Social Movements.Footnote 9 Although the cases discussed in this 2012 book relate to a broad timespan, the role and characteristics of charismatic leadership in socialism and anarchism between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries feature prominently.Footnote 10 These studies allow us to overcome the conventional approach to the phenomenon as a manifestation of a childhood of the masses and as an obstacle to or danger for the emergence of political awareness, showing that charismatic leadership – while maintaining a somewhat ambiguous nature – is actually an integral part of modern politics that, in certain contexts of transition, can serve to achieve democratic “participation and involvement”.Footnote 11 Therefore, the rejection of the common use of the concept of charisma in terms of personality type and of purely manipulative power adheres to an interpretation of Weber’s relational approach stressing the importance of contextual factors. In this regard, the charismatic leadership in the growing socialist and anarchist movements is interpreted as a relationship between leaders and followers often reinforced by an emotional communication style through which participation and consciousness could be stimulated in a context of social crisis and emerging mass parties. Furthermore, as recalled by Te Velde in an earlier article published in 2005, the list of charismatic leaders emerging between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is rather long and includes a prominent presence of “prophets” who could mobilize the masses in all European countries.Footnote 12 From this perspective, Italy is no exception. In keeping with this line of research, this essay addresses the case study of the Italian anarchist Pietro Gori, whose popularity shows qualities that seemingly evoke – through a range of aspects – the experience of other leaders, in particular that of the Dutchman Domela Nieuwenhuis.Footnote 13

In Italy, Gori’s popularity had a paradoxical effect. Until the Fascist period, Gori was seen by socialist militants as a precursor of the Italian Socialist Party, despite a political career that would relegate him to the role of a diehard opponent of this party. In 1892, he was one of the protagonists of the battle that took place in Genoa between anarchists and socialists, ending with the definitive separation of the two movements and the founding of the PSI (the Italian Socialist Party).Footnote 14 However, both at the outbreak and at the end of World War I, Gori’s image featured in a series of postcards and pictures designed by the PSI’s publishing house and dedicated to its socialist precursors.Footnote 15

Until recently, the significance of Gori’s presence in the Italian socialist pantheon, as well as many aspects of the position he held in the national labour movement, have barely been considered in academic research, and were relegated to mere footnotes. The relevance of Gori as a major player in the Italian context has really only emerged in the last two decades. This “rediscovery” is due to the radical changes in the approach of traditional research towards political movements during the liberal period at the turn of the twentieth century in Italy. The interest in Gori also relates to the emergence in the 1990s of a perspective inspired by the French Annales School and of a culturalist approach pioneered by the historian George Mosse within the field of study of the Italian labour movement. This, in turn, has led to a rereading of the mental make-up, culture, and systems of communication of the period between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.Footnote 16 Indeed, Gori has emerged from the shadows, mainly as a result of the trends of general historiographical interests in popular sentiments and in the emotional style of “new politics” arising in the late eighteenth century.

This article analyses Gori’s charismatic leadership, shared with Malatesta, of the anarchist movement from 1897–1898, a period that saw one of the largest pre-fascist uprisings in Italy. The aim is to investigate Gori’s political communication in one of the periods with the greatest political and social tension, a time when a new strategy for the anarchist movement was conceived. Gori’s work is analysed within the context of the broader international network, which aimed to develop a political strategy that focused on organizing the anarchist movement beyond its traditional spontaneous components.

THE ANARCHIST LEADERSHIP IN THE ITALIAN CONTEXT

The centrality of the leadership in the Italian socialist and union movements in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has been repeatedly emphasized by various studies since the 1990s. Historians maintain that, from the end of the nineteenth century, in Italy, as well as elsewhere, in both North America and Europe,Footnote 17 the charisma of the leaders was crucial in motivating broad political mobilization at the local level. As noted by Carl Levy, Italian anarchism, particularly in periods of tension and protests, relied to a heavy extent on the leaders within a movement that – despite its system of informal networks – was characterized by organizational weakness. In this regard, the case of Malatesta in the Red Biennium (1919–1920) studied by Levy is exemplary of the mobilizing effect of personality, even though Malatesta’s style of communication was, in fact, far from charismatic. Indeed, Levy reconstructs the force of a heroic symbolic transfiguration wrought by the popular classes and the press that had little to do with Malatesta’s personality.Footnote 18 As remarked by Maurizio Antonioli, Malatesta’s style rarely made use of specific speech patterns and emotional body language. Instead, it adhered to a rational and well-organized communicational model, which Levy called Socratic, and which may be associated with Mazzini’s educationism.Footnote 19 From this point of view, Malatesta is almost the antithesis of his friend Gori. Yet, Gori also stood out from other leaders within the movement, such as Luigi Fabbri, one of his friends who disseminated Malatesta’s views, and Armando Borghi, a key figure in anarchic syndicalism. Reluctant to indulge in an overly literary and emotional dimension of politics, they both adopted and evoked forms of expression that were more akin to Malatesta’s style, focusing on greater political rationality.Footnote 20

In his pioneering study on the Italian myth of Gori, Antonioli identified a clear correlation between Gori’s popular heroic-religious image and what he deliberately attempted to transmit to the public. His contemporaries frequently referred to Gori in terms of a Christ, a visionary, an apostle. Antonioli attributes this – at least in part – to Gori’s powerful emotional style in terms of communication devices and messages. Gori’s oral and visual forms of expression coincided with the popular sentimental universe: singing, theatre, poetry, speeches, and conferences were the fora for intense contact. The power of these instruments was decisively reinforced by Gori’s use of figures and metaphors rooted in tradition and in the lives of multitudes of people, such as his constant references to the experience of emigrants as people who were forced to go in exile.Footnote 21

More recently, Marco Manfredi suggested that the figure of Gori in Italy has become established in popular memory especially thanks to his role as a powerful speaker, addressing his audience in artistic ways even when discussing political issues. He was, therefore, able to create a strong sense of political awareness among his audiences. His skills in using both verbal and body language, which came from literature and social theatre conveyed in language with religious overtones, were at the core of a powerful political discourse.Footnote 22 Manfredi highlights that Gori’s return to Italy was linked to a new liberal openness that for anarchists would provide the backdrop for a “media revolution”. In short, the start of the twentieth century was the advent of “a stable and organic political propaganda”Footnote 23 for both Gori and Italian anarchism.

These interesting analyses address some of the most intriguing aspects of anarchism and Gori’s work. Nonetheless, albeit with several references to political conferences, both Antonioli and Manfredi investigated Gori’s work primarily as a poet, writer, and playwright. These analyses explored various major communication tools, but did not cover the entire range of political communications used by Gori. Moreover, neither Antonioli, nor Manfredi included the development of anarchist organization in their work and, more broadly, the social and political experiences that occurred during Gori’s activities. Lastly, in contrast to Manfredi, I would argue that Gori’s popularity did not emerge in the early twentieth century when new liberal freedoms were being granted, but earlier, at the time of governmental repression when momentous changes were taking place in the anarchist movement.

GORI AND THE ART OF COMMUNICATION

The new liberal phase certainly provided new communication opportunities, as well as new channels for the development of a solid propaganda project. However, if one examines the direction taken by Gori in Italy in terms of communication techniques, the last decade of the nineteenth century was, in some respects, even more important than the following one. Between 1890 and 1894, during Malatesta’s exile, Gori and Luigi Galleani delivered speeches at dozens of conferences and were considered to be the two most effective propagandists of the time.Footnote 24 In the same period, Gori wrote almost all of the poetics of 1 May, as well as dramas including the famous Inno del primo maggio (the anthem of 1 May),Footnote 25 all of which were analysed by Antonioli. Most of Gori’s poems on Labour Day immediately circulated among the popular propaganda and were then recited or sung at parties or in small meetings both in Italy and in the communities of Italian emigrants.Footnote 26 For the theatrical productions and the Inno, the expat community in the United States was almost always the first to benefit from the performances, and Gori is credited with making 1 May May Day in the US.Footnote 27 Emigration networks acted as a channel of communication outside the US. In 1897 in Italy, there were the first representations of the Primo maggio (1 May) sketch in the US version, where the famous anthem soon became one of the best-known and longest-lived pieces of the labour movement.Footnote 28

The Italian circulation of dramas was a piece of propaganda organized by Gori on his return home in late 1896. However, between 1897–1898, Gori’s agenda focused on other activities; primarily his legal profession. At that time, Gori had already built part of his success through the trials – especially those in 1894 in the aftermath of the Sicilian revolts and the insurgencies in the north of Tuscany – that culminated in a harsh crackdown. In a note to the local authorities in May 1894, Prime Minister Francesco Crispi, who was the architect of the repression of the anarchists, tried to put a stop to Gori’s legal practice in north-central Italy, which Gori had been conducting with conferences “in smaller rural centres” where the trials were held.Footnote 29 At that same time, Gori’s reputation for being persecuted was being consolidated by the seventeen cases against him in 1893.

As recalled by his friend and collaborator Ezio Bartalini, to prevent the debates from becoming opportunities for political propaganda for Gori the authorities began to occasionally conduct trials behind closed doors under the pretext of public order.Footnote 30 Another striking example of the widespread fear of Gori appearing in court, even at an international level, is provided by his expulsion from France in 1894 for fear that he might take on the defence of Sante Caserio, who had assassinated the French President Sadi Carnot.Footnote 31 Moreover, the revelation of past relations between him and Caserio fuelled Gori’s notoriety enormously in France, where he was considered to be the instigator of Caserio, or the “Italian Sébastien Faure”.Footnote 32

Back in Italy, Gori and Malatesta used the trials to forge a formidable propaganda strategy. The criminal proceedings, especially the debates in the Courts of Assizes, were some of the greatest spectacles of the time.Footnote 33 In the late nineteenth century, democrats, socialists, and anarchists made full use of court oratory for educational purposes and to form a personal and party consensus. This approach renewed and reinforced a tradition that already existed in the internationalism of the 1870s. A good example is the famous trial of 1876 brought against several internationalists accused of undermining internal state security for an attempted insurrection. The defendants also included Andrea Costa, a founding father of Italian socialism. For the socialist leaders Filippo Turati, Leonida Bissolati, Errico Ferri, and Anselmo Marabini, Andrea Costa’s self-defence in court would mark the moment of their entry into politics. Furthermore, Marabini – a fellow countryman of Costa – provided a very interesting testimony in his memoirs about the spectacle of this occasion. According to him, for three months, crowds flocked to the Court of Assizes, people in the square would talk of little else than the hearing, and the citizenry celebrated the defendant’s acquittal. The text of Costa’s self-defence went on to become a true bestseller.Footnote 34 More than twenty years later, the judicial arena would continue to be vital for all political forces, but especially for the anarchist movement, as suggested by Antonio Gramsci.

In his Prison Notebooks, assessing the deep roots of “generic libertarianism” in popular traditions in Italy, Gramsci suggested that Gori’s poetry and speeches should be analysed, as they played a key role in fostering a taste for melodrama amongst the people.Footnote 35 Reflecting on ways to eradicate this taste, especially in poetry, Gramsci came to perceive “collective oratorical and theatrical events” as one of the causes behind this trend towards melodrama. When discussing oratory skills, Gramsci specified that one should not “only refer to popular meetings”, but also gatherings at funerals, the courts, and popular theatres. In the provinces in particular, the judicial offices were crowded with a “popular” audience and “elements that imprinted in the memory the turns of phrase and the solemn words, they meditate on these words and remember them. Likewise, in the funerals of notables, attended by large crowds, who often only came to hear the speeches”. Ultimately, in order to eradicate such pre-political melodramatic taste, Gramsci advocated “its merciless criticism” and the dissemination of “books of poetry written or translated in ‘unrefined language’, where the sentiments expressed are not rhetorical or melodramatic”. An example of this was the “simple translations, such as those of Togliatti for Whitman and Martinet”,Footnote 36 published in the Gramscian journal Ordine Nuovo between 1919 and 1920.Footnote 37

Not only did Gramsci regard the statements in court as powerful, pernicious, educational tools, he also considered the spread of the judicial genre and its political exploitation by the anarchists to be dangerous for the masses. Gramsci wrote in his Notebooks that at the Socialist Party Conference in Livorno in January 1921 – which saw the split that resulted in the founding of the Communist Party – the socialist MP Pietro Abbo “repeated the introduction of the statement of the principles of Etievant” pronounced at the Court of Assizes of Versailles in 1892. Pietro Abbo was a self-taught farmer born in 1894 and, according to Gramsci, Abbo’s source was Luigi Galleani’s collection Faccia a faccia col nemico. Cronache giudiziarie dell’anarchismo militante [Face to face with the enemy: Judicial reports on militant anarchism], published in Boston in 1914. The case was mentioned as an example of how “these men educated themselves” and how “this sort of literature” was “widespread and popular”.Footnote 38

THE POLITICS OF COMMON SENSE

On 1 May 1897, Malatesta wrote: “let’s see trials as an opportunity for greater and noisier propaganda”.Footnote 39 His exhortation was part of a broader appeal to use all the spaces of freedom to promote the political project of organized anarchism that had recently been developed by those in exile. Indeed, from 1895, in the international community of exiles in London, a concept of Italian and French organizational anarchism had begun to develop. London was then the crossroads of continental anarchism, which had been hit by a wave of repression triggered by anarchist bombings and rioting.Footnote 40 The failure of these bombings and riots, the subsequent governmental repression, the impact of the great European popular mobilizations and trade unionism acted as catalysts for a review of anarchist strategy. The French and Italian groups in London, headed by Malatesta, Pouget, and Pelloutier, were jointly formulating new guidelines for national and international trends based on the idea of internal organization and the strong involvement of anarchists in the labour movement.Footnote 41

Gori was directly involved in this collective gestation of a “labour-oriented” strategy in order to regain contact with the masses. In 1895, he stayed for a few months in London, immersing himself in the life of the international anarchist network until his departure for the United States.Footnote 42 These discussions in London provided the background to the direction he was to take in the US. In North America, hundreds of conferences and theatrical performances had the purpose of raising awareness of the kind of anarchism championed by Malatesta and other organizationists.Footnote 43

The end of Gori’s tour of America was linked to the decision taken by the organized branch of anarchists to assert their new tactics to the maximum at the assembly of the international labour movement in London. With the mandate of various Italian trade unions in North America, Gori returned to London to take part in the fourth Congress of the Second International (27 July to 1 August 1896), which witnessed the last heavy battle between the front tied to the German SPD and the “anti-authoritarians” made up of anarchists and various socialist components. The Congress was the most important event for Gori and Malatesta before returning to Italy, where they set out a programme that contrasted individualism, terrorism, and spontaneity with an entry into the world of work and an operational strategy that set aside the revolutionary framework.Footnote 44 The main tool to propagate this programme became the weekly L’Agitazione, founded in Ancona in March 1897, in which the voices of Malatesta, Gori, and other organizationists outlined guidelines for a people’s strategy focused on economic campaigns and legal battles for civil liberties based on an agenda modelled on the existing order.

For Malatesta and Gori, these new guidelines were the clearest signs of a strong-felt need to “go to the people”, which had informed previous thoughts and actions. As reconstructed by Davide Turcato, the path taken by Malatesta in the late nineteenth century is marked by a permanent drive for inclusion and flexibility. “Going to the people” was based on participation in labour and civil battles, which could not be traced directly back to anarchism.Footnote 45 As mentioned earlier, Gori’s constant penetration of the world of ordinary people was the aspect most referred to by historical studies. In 1897, this resulted in appeals for the use of a language of the soul and in an absolute leadership in defence of civil liberties. In June 1897, Gori announced his resumption of “work” in Italy in the L’Agitazione by launching an appeal to speak to everyone using “the simple words of a good heart” of “common sense” in the name of “human solidarity” and to enter “boldly, without further separating himself, into the labour movement”.Footnote 46 A little over a month later, in keeping with the line of L’Agitazione, he outlined a priority action plan for the anarchists: the struggle against a bill “that essentially aimed to include the actual deportation by administrative action in the permanent legislation of the state for political reasons”.Footnote 47

The return of Malatesta and Gori coincided with the discussion on a reform aimed at normalizing the violation of freedom of expression which – in contrast with the fundamentals of liberalism – was implemented by the Italian government as an exceptional measure between 1894 and 1895. A text on domicilio coatto was under discussion, i.e. confinement in a – usually remote – town or in a prison camp, which would make any stable form of organization of dissent and freedom of expression very difficult. Domicilio coatto was used constantly to suppress expressions of opposition to the liberal system.Footnote 48 The exceptional measures in 1894, however, made domicilio coatto practically embedded in the rule of law to repress anarchists, socialists, and even republicans.Footnote 49 The resulting indictments and convictions were based on the political programme of the Socialist Party and the anarchists. When these temporary measures ceased to be in force, first Crispi, and then his successor Antonio Rudinì, attempted to transpose them into ordinary law.Footnote 50 Indeed, in 1897, Rudinì revived the project on the back of political elections that had given the extreme left more than a quarter of the vote.Footnote 51 In the version approved by the Senate, the basic substance of the law was essentially the same as in the exceptional measure of 1894.Footnote 52 In fact, political programmes, articles, brochures, posters, conferences, or simple cries of “long live anarchy” or socialism, would constitute an offence punishable by domicilio coatto.

Faced with this proposal, Gori saw the need to move in at least three directions. In his article “Per la libertà” [For Freedom], he first urged anarchists to take up their battle through a call to the “partisan government” to act in decency and show “respect for their own statute”. His call also sought to debunk the anarchists’ image as “inhuman haters”, which had been corroborated by the attacks in recent years, by highlighting the recently developed programme of organized anarchists. Secondly, Gori recognized that he had to act together with the other left-wing groups that were already operating in that sphere. Lastly, the campaign had to become a popular movement. Against the laceration of the “few Italian freedoms” that were left, “the people”, Gori wrote, “have a duty, not just a right, which is wholly constitutional: resistance”.Footnote 53

This sort of manifesto came out shortly after the publication of the first of many reports regarding the legal practice Gori conducted in the centre-north of Italy. The anarchist was back in the courtrooms, turning them into a stage for the project promoted by L’Agitazione, which was no less effective than the rallies that were denied to him due to being on parole.Footnote 54

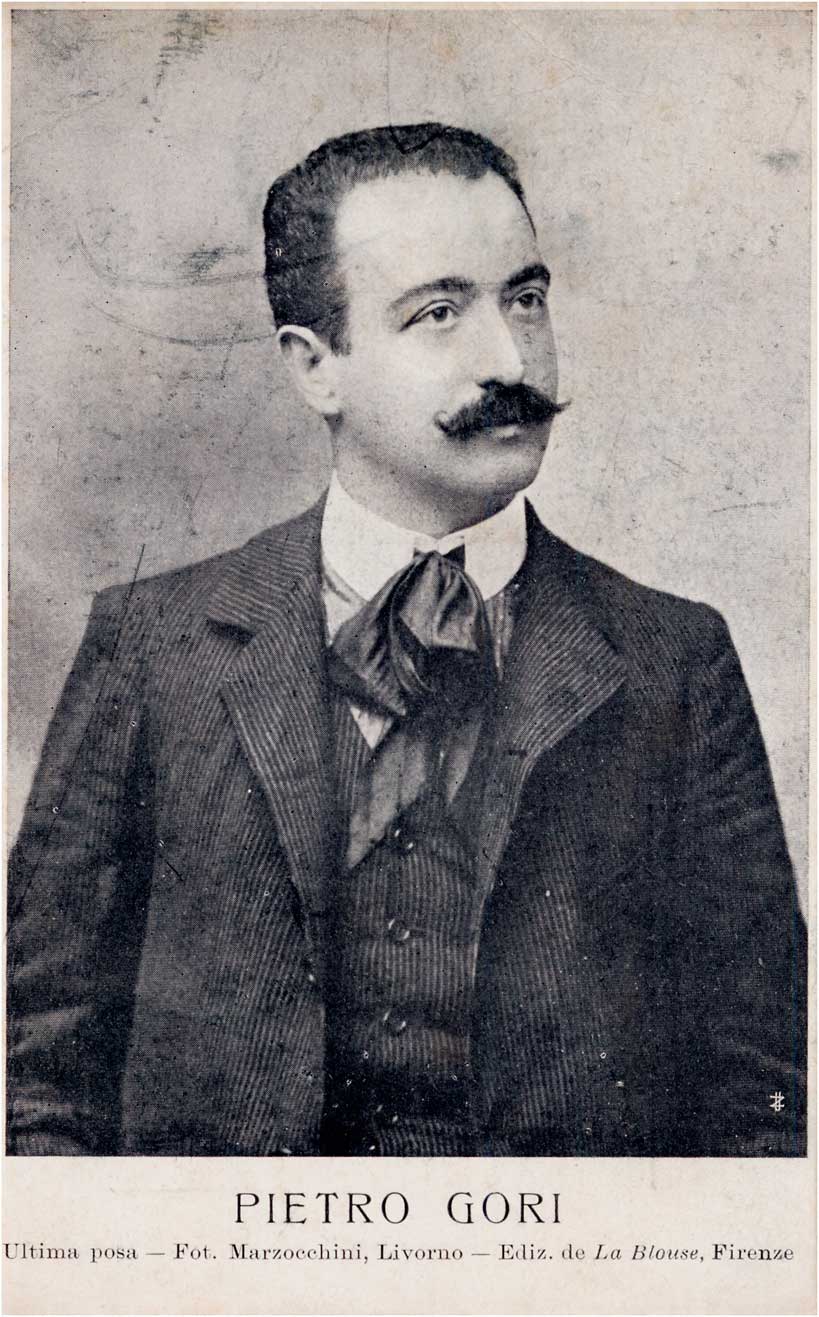

Figure 1 Pietro Gori. Source: Archivio storico fotografico della Biblioteca F. Serantini di Pisa. Used with permission.

FROM THE PERIPHERY TO THE CENTRE AND BACK AGAIN

Two trials that took place in 1898 can be used as examples to assess the Per la libertà [For Freedom] project alongside Gramsci’s comments. One was a trial of thirty-six citizens of Carrara, the epicentre of the 1894 riots, and the second was the famous proceedings against Malatesta and the editorial staff of L’Agitazione. The first case was triggered by the attack on a public safety officer. Republicans, socialists, and anarchists were charged with unlawful association, the possession and detonation of bombs, and attempted murder. The trial was held in the Assize Court in Casale Monferrato (Piedmont) from the beginning of March until the end of April, and concluded with the acquittal of all the defendants except one. The attack on the public safety officer was interpreted as a manifestation of a subversive plan aimed at abolishing private property by violent means, and was seen as involving all of the popular political forces through the indiscriminate attribution of the markings of anarchism. The prosecution was based mainly on posters celebrating 1 May 1896, on municipal commemorations, and on an 1883 statute of the anarchist “sect” based in Carrara.

From the outset of the proceedings, Gori was present as a member of the defence. In the courtroom, there were journalists from six newspapers, including two from Carrara, two from Turin – Gazzetta del Popolo and the national newspaper La Stampa – and two local papers L’Avvenire and L’Elettrico. There were 260 witnesses, and the doors were always open to the public.Footnote 55 The whole trial was reported verbatim by the two Carrara weeklies Lo Svegliarino (the mouthpiece for the Republicans with a circulation of around 1,000 copies) and the moderate democratic L’Eco del Carrione.Footnote 56 Gori gave his speech on 13 April before an “unusually crowded” courtroom.Footnote 57 The local newspapers noted that Gori had set up “a barricade of books”Footnote 58 and L’Eco del Carrione reported at least some of the titles of these books.Footnote 59 In some cases, book titles were reported without the name of the author, while in others the titles were inaccurate. Essentially, there were three types of book, some of which were in French and Spanish: political writings on international social anarchism, classic essays, and books that had been extremely successful within the broader context of radicalism, as well as at least two publications by Gori. This “barricade” was, therefore, of a multifaceted nature and could not be attributed solely to the anarchist doctrine. Nevertheless, this range of titles was able to help spread true anarchist ideas and build a bridge with other forces and middle classes, who had long been familiar with the interpretations and radical messages that Gori put forward.

The political writings on social anarchism included books in French by Kropotkin, Paroles d’un révolté, and by the Dutchman Domela Nieuwenhuis, Le socialisme en danger, as well as Spanish works by Mella and the Georgian writer Tcherkesoff. The writings by Mella and Tcherkesoff, Los sucesos de Jerez and Páginas de historia Socialistas, respectively, were some of the titles published or promoted in 1897 by the newly formed Protesta Humana in Buenos Aires, a Spanish-language weekly inspired by the writings of Malatesta, which would soon become the most important anarchist journal in South America. In fact, Gori appeared with at least four books and brochures in Spanish that were in the Protesta Humana catalogue, comprising around ten titles, including Gori’s dramatic sketch Primero de Mayo published in 1897.Footnote 60

Consequently, Gori managed to take into the courtrooms the key works of international social anarchism; some of the authors he had met between 1895 and 1896 in Amsterdam, London (where Russian exiles and Russophiles were often based), and the United States.Footnote 61 This propagandist showcase of books was a way to disseminate the ideas of the organized anarchists before the Italian versions of the works by Italian publishers were released. For the occasion, Gori’s barricade also included the minutes of meetings and a copy of the Philadelphia newspaper Il Vesuvio, whose chief editor was the radical socialist Giusto Calvi, with whom Gori had argued in the United States. In response to Calvi’s criticism of the anarchist ideas and practices outlined in the Avanti of Philadelphia, Gori blasted him in the pages of the Italo-American Questione sociale. In his famous long piece entitled “Anarchici e socialisti” [Anarchists and Socialists], Gori criticized electoralism and parliamentarianism and focused on the socialist nature of anarchist economic doctrine.Footnote 62 To strengthen the anarchists’ position as the true interpreters of genuine socialism, Gori used instrumentally Auguste Bebel’s brochure The Conquest of Power and drew on the author’s references to the inevitable demise of the State.Footnote 63

This pamphlet, by one of the fathers of social democracy, had been well-known in Italy for years. This notoriety suggested that it was part of the showcase of books for the trial. The pamphlet falls into the second category of books that Gori proposed for the courtroom, including some Italian and European bestsellers on radicalism: Le socialisme contemporain by De Laveleye, The Life of Jesus by Renan, La fine delle guerre [The End of War] by Meale (whose pseudonym was Umano), La sovranità popolare [Popular Sovereignty] by Ellero, La dottrina dei partiti politici [The Doctrine of Political Parties] by Bovio, and La delinquenza settaria [The Sectarian Criminality] by Sighele. These authors made up the cultural background of a generation of speakers from different political affiliations (anarchists, socialists, radicals, republicans), who often shared the experience of having studied law at university.Footnote 64

With regard to his speeches, Gori did not address controversial themes and terms that would have brought to the fore differences between anarchism and other leftist political movements. Gori made absolutely no reference to the charges brought against the accused. Instead, he focused on the nature of anarchism and on the non-prosecutability of this political doctrine. By instigating a sort of counter-trial against the public authorities, he exalted the liberties of England, defended the Italian constitution, and revived the teachings of the liberal law school and social criminal law cultivated by socialism.

At the same time, in defence of anarchism, he made frequent use of the rhetorical and linguistic devices typical of both radical democracyFootnote 65 and of socialism and anarchism from the continent. Gori exploited the popular myth of Jesus being a socialist.Footnote 66 The essence of anarchism was defined by both the old and most recent transfiguration of Jesus conveyed through democracy and socialism. Indeed, when asked to define anarchism, Gori replied by quoting the Jesus humanized by Renan, while also referring to the Bible.Footnote 67 Furthermore, the right to association and speech for anarchists was claimed through the stories of persecutions against Christians conceived by Félicité de Lamennais and later appropriated by the liberal and radical political culture of 1848. Gori argued that anarchism may be “a dream, a utopia”, but for the innocent accused of the crimes, “we [anarchists] demand freedom through the words of a priest, Lamennais, who recommended that his flock should respect all opinions and remember the catacombs where Christians died because of the God they had chosen”. In a similar vein, to further argue in favour of freedom of speech, Gori referred to the Risorgimento myth of the conspirators/martyrs who had died for the freedom enshrined in the Albertine Statute, which was then celebrating its fiftieth anniversary. Gori emphatically stated: “I bow to the Statute, the result of the blood of conspirators, of yesterday’s persecutors, and […] freeing the accused you [the jury] will assert this sacrosanct right to freedom”.Footnote 68

The framework, themes, and images of these criminal proceedings were replicated in the trial brought against the editors of the L’Agitazione, who were accused of directing the riots against the high cost of food in Ancona in January 1898. Malatesta and his companions were indicted of the crime of criminal association and criminal apology. The case ended, however, with a conviction for sedition, which was a rather more noble crime for the anarchists than simply being seen as common delinquents.Footnote 69 The evidence was found in the publications of L’Agitazione, in Malatesta’s Fra contadini, as well as in Malatesta’s conferences on domicilio coatto and social anarchism. The records of the hearings show the presence of republicans, socialists, and anarchists as defence witnesses, some of whom had previously participated in conferences with Malatesta on the issue of domicilio coatto. Outside the tribunal, a crowd waited patiently hoping to be allowed to take part in the proceedings.Footnote 70

Being fully aware of his theatrical presence, Malatesta turned the questioning and self-defence into a display of anarchist doctrine and of the organizationists’ recent programme, with a renewed focus on becoming closer to the working class. As always, his oratory style was simple, direct, but not without emotional outbursts.Footnote 71 The structure and language did not diverge from the first part of the defence conducted by Gori, who was wisely the last of the attorneys to speak before Malatesta’s final self-defence. Gori’s speech can be divided into two parts. In the first half, he read pages from Malatesta’s L’Anarchia (1891), considered by Malatesta to be his best work, to which he added several typical ideas of anarchic socialism, such as freedom from authority, economic and social harmony, and the rejection of violence. Gori saw violence as a by-product of authority, identifying it as something belonging to the bourgeois state, and contrasting it with the image of anarchists who were prophets of a new peaceful and just world.Footnote 72

The second part of his speech, however, was designed to invoke freedom of thought and action for the movement. He therefore harked back to the link between anarchists and Jesus and between anarchism and Christianity. Gori claimed that judges cannot “nail” the anarchist principles of freedom, harmony, and justice to “the cross of those two articles of the criminal law code”. Gori drew an analogy between the anarchists’ crucifixion and that of Jesus: “the cross became the symbol of purity when the gentle Jesus was crucified as a wrongdoer […] who raised his voice against the rich and the powerful of the world in the name of the wretched and the humble”.Footnote 73 On this basis, Gori suggested that anarchist humanism represented the highest stage of Christianity.

At the same time, Gori advanced the idea of a lineage of anarchists from the Risorgimento generation who were attempting to reclaim freedom; moreover, he put forward a vision of predestination which, once again, was based on icons and symbols of democracy. Employing a positivist approach, Gori extracted words from Giosuè Carducci’s Satana e Polemiche sataniche [Satan and Satanic Polemics] on the clear direction of history towards socialism as testified by the French insurrection of 10 August 1792, by the Five Days of Milan in 1848, and by the Parisian barricades of June 1848.Footnote 74 Gori thereby proposed three interlinked types of prophets/martyrs: the evangelicals, the democratic revolutionaries of the Risorgimento, and the anarchists – all persecuted and betrayed in their ideals, but not defeated.

Simply dismissing these passages from Gori’s oration as being the legacy of a flair for melodrama and a post-Risorgimento romantic-democratic culture would be to misunderstand several fundamental aspects. In actual fact, the language adopted is the manifestation of a more complex strategy. For Gori, Malatesta’s “going to the people” meant primarily speaking in a way that could arouse empathy among an audience that was still largely illiterate. Gori was known by his activist companions and friends as a “true expert of the doctrine” of anarchism, but not as a theorist; he was continually engaged in developing popular forms of communication.Footnote 75 According to Luigi Fabbri, the Tuscan anarchist had remarkably solid ideas and was able to “heed the most daring affirmation of the theories and methods of anarchism” in varying contexts.Footnote 76 While he was able to win over many different audiences, Fabbri stated, “he also knew how to enthuse his much-loved crowds of ordinary people”.Footnote 77 On this note, he wrote: “his eloquence [...], in its beautiful form, was accessible to the hearts and minds of all workers, even those less well-educated. He didn’t show off with unintelligible words [...] he spoke the language of the people”.Footnote 78 As such, the language of the people, to which he dedicated his life, went from using simple vocabulary to employing figures and symbols that were deep-felt in popular culture, yet which Gori was able to infuse with new substance. The poor and mistreated Christ was one of the most popular images among the European masses, along with the martyrs and heroes of the European revolutions of 1848, such as Giuseppe Garibaldi, who were true popular icons.Footnote 79 People’s widespread familiarity with these traditions is the reason why they are referred to by Gori with an anarchist approach who, in doing so, took the same path as other European leaders such as Domela Nieuwenhuis, operating in contexts with major party-political instability and significant social changes. Between 1885 and 1891, in order to popularize the socialist ideas, Domela Nieuwenhuis very successfully employed a speaking style that had numerous references to the humanized Jesus.Footnote 80 As for Gori, the power of this style is confirmed by the testimonies of the local peasants and workers from the anarchist’s place of origin (Elba). In court, the anarchist leader was reported to have “had incredible words” that won people over,Footnote 81 “sincere words” that made people like him.Footnote 82 The “incredible words” “awoke” people to the idea of “having citizen rights, the rights of men not of beasts”.Footnote 83 In popular Tuscan memory, the courtrooms, town squares, theatres, and workplaces were all places where Gori had “sown ideas”,Footnote 84 which later gave rise to the establishment of anarchist syndicalism.Footnote 85

As in the case of Domela Nieuwenhuis, the mechanics of interplay with the people were simultaneously reinforced by life practices that were similar to both the Christological model and that of ordinary people.Footnote 86 In popular memory, the Italian anarchist leader was remembered as an “angel”, an “exceptionally good” man, “all heart, all heart for everyone”.Footnote 87 The “saint”,Footnote 88 however, was also depicted as the one who “saw people as his own [...] there was no distance”.Footnote 89 According to a farmer from Elba, the “older ones” said that Gori “was always among the people”.Footnote 90 The memory of the inhabitants of Elba suggests that, together with this lifestyle, it was his legal defence for common crimes that played an essential role in connecting Gori with the people. The deep empathy felt towards the anarchist stemmed from the fact that he was viewed as the unpaid lawyer of the poor. In many people’s memory, Gori was “fair”,Footnote 91 a man of justice, as he defended those who were displaced and exploited without receiving payment, and was almost always successful thanks to his eloquence, which “broke hearts”.Footnote 92

While the model of an anarchist Christ among men – so strongly articulated in advocacy – helped to create an emotive community and “awaken” the people, in the political processes of 1898 his proposition served an even broader purpose. The representations and images used in the courtroom managed to convey anarchists in a light that was the opposite of the image of wrongdoers-destroyers, thereby helping to legitimize the movement as a force that could address the issue of rights and interacting with socialists and democrats.

These forms of communication developed at a time when protests were spreading rapidly across Italy and at the climax of a process of rapprochement between political forces on the left. Gori drew on myths able to consolidate his own political community and to achieve broader political objectives by supporting and strengthening an area of common ground with republicans and socialists. This goal was achieved in autumn 1897 despite persisting tensions between these forces.Footnote 93

Until the eve of the trial, L’Agitazione provided news about anarchist, republican, and socialist conferences and rallies held to defend freedom and joint committees for the abolition of domicilio coatto. Representatives of various popular forces were taking part in all of these initiatives. Especially in central Italy, solidarity and cooperation were expressed in a variety of forms at a local level. In addition to joint committees, there were collective commemorations focusing on the freedom of expression, and funerals for those condemned to domicilio coatto attended by some of the key political figures fighting the proposed new legislation.

Gori did not limit himself to speaking in court, but took advantage of all kinds of public platforms. His numerous defence cases were interspersed, for example, by participating in the funeral of a “victim of domicilio coatto”, and in a huge demonstration in Pisa in honour of Giordano Bruno. Gori attended the funeral along with Luigi De Andreis, a republican member of parliament and member of the central committee for agitation against domicilio coatto, who was later sentenced in 1898 to twelve years in prison by the Milan War Tribunal.Footnote 94 Gori and De Andreis therefore transformed the event into a political gesture with highly symbolic content rooted in continuity with a nineteenth-century tradition. Equally important was the commemoration in Pisa of Giordano Bruno who, along with Galileo, was seen by all radicals as the main deity of freedom of thought.Footnote 95 The tribute to Bruno included the unveiling of a plaque and a meeting with the three proponents of the battle against domicilio coatto: Gori, the republican Faustino Sighieri, and the socialist Andrea Costa, who had recently been deemed a major contributor to the weakening of the anarchist movement and who had therefore been subject to a harsh campaign of accusations by anarchists.Footnote 96

Another significant opportunity to bring together different political movements was the celebration of the Five Days of Milan, which took place in March 1898 and was organized by republicans, socialists, and anarchists in defence of freedom and against domicilio coatto. At the height of the protests, which coincided with the official celebrations for the fiftieth anniversary of the Statute, the radical movement recalled the “other 1848” when Milan witnessed a huge mass gathering with the significant presence and influence of democratic elements. In what was one of the main collective rituals of popular movements, violating parole, Gori gave a speech on behalf of the anarchists which – to a great extent – was a revisited version of the famous and enduring Inno di Garibaldi by Luigi Mercantini (1859). Gori developed his address by highlighting the experience of the lower classes and by drawing on some Risorgimento categories, interpreted in a way which was common to radical democrats and socialists.Footnote 97 Gori’s rhetoric was centred around three nuclei: the homeland dreamed of by Pisacane, the betrayed homeland, and the homeland finally redeemed. Gori filled his speech with powerful images. He appealed to the 1848 martyrs/patriots who fought and died dreaming of “social justice and freedom”. Despite their sacrifice, he highlighted that “the homeland, mother to all of her sons”, still did not exist. The betrayal of the motherland was demonstrated by the thousands of emigrants – “sons of Italy, wandering around and mocked” – and by the oppression of the political opponents (described as “apostles […] of redemption”). However, in a prophetic style typical of his time, he declared that the spirit of the 1848 Milan patriots would rise again on the final day of “the Nemesis hour”. On this day, people will sing, in Garibaldi’s footsteps, the verses of Mercantini’s Inno: “Italian houses are made for us” and “our martyrs have all risen again”.Footnote 98

As such, Gori described the last victory as the completion of the fathers’ unfinished plan. The redemption took the form of an awakening of the spirit of 1848 against the nuovo straniero (the new oppressor, the bourgeois state). This awakening would inexorably lead to the “final liberation from economic injustice and political tyranny”.Footnote 99 The sheer power of this type of rhetoric is highlighted by the fact that, two months later, Gori’s speech appeared in the documents presented by the prosecution at the trial brought against him by the Milan War Tribunal, which ended with an eight-year prison sentence.Footnote 100 The sentence was issued when Gori had already left for Argentina, where Protesta Humana had continued to publish Gori’s work. Just before his arrival, the paper had consecrated him as the poetic symbol of May Day.Footnote 101 Gori’s landing in Argentina ushered in a period that shared a great deal with his experiences in Italy. Gori embarked on the same range of endeavours and types of speeches. From the outset, he set about denouncing the current situation in Italy in a theatre, but political awareness soon came thanks to the launch of a pamphlet – La anarquìa ante los tribunales: defensa de Pedro Gori en el proceso de los anarquistas de Génova – and the publication of Malatesta’s trial.Footnote 102

CONCLUSION

A turning point for the organizationists of the Italian anarchist movement came only after the liberal breakthrough in 1901, which enabled the anarchists to be protagonists of the foundation and activities of the Camere del Lavoro in the large cities of north and central Italy. From 1902 onwards, this development was supported by Gori, whose patronage was sought given the popularity he had achieved in the previous decade. Gori’s leadership depended to a large extent on his ability to exploit – rather than invent – modern political communication. Like in France, the use of traditional stages for a political show in a repressive phase played a key role in creating an aura of epic quality.Footnote 103 Funerals, celebrations, theatrical and poetry events, as well as the courts of law, were the typical paraphernalia of modern politics heralded by the French Revolution,Footnote 104 while the repression increased their visibility and fortune.

In these contexts, Gori utilized communicative tools that were criticized by Gramsci, but turned out to be very effective. In the Quaderni, Gramsci expressed several negative comments on Gori’s libertarianism, with reference to his rhetoric, and not to a specific political project. Gori was not a theoretician, but someone with a profound knowledge of the anarchist doctrine – as acknowledged by his comrades – whose goal was primarily that of developing popular forms of communication. Above all, Malatesta’s “going to the people” (andare al popolo) meant, for Gori, the need to conceive a language for the people. In a context characterized by illiteracy, deep popular religious feelings, lack of structured political parties, and state repression of political activism, Gori’s communicative style was able to reach widely into society. As shown by the performances in court, the use of symbols and deep-felt myths served to achieve emotional appeal that opened up the field or could be combined with an attempt to disseminate the anarchist doctrine developed largely by the international community of exiles. In this regard, remembering Gori as a jurist, his friend Bartalini described the court as a place both of “sentimental communion” and “a propaganda conference [...] where the lawyer and clients” could celebrate “a rite of freedom”.Footnote 105 More generally, thanks to his emotional-religious style, Gori sustained an image of anarchists very different from that of “human haters”, which was common during that period. At the time of raising political violence, this aspect was crucial in order to legitimize anarchism as a political force able to relate with other political movements and to address the issue of political and social rights.