For the quarter of a century following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the English and the Dutch states maintained armies that generally numbered around 100,000 soldiers or more (Brewer Reference Brewer1989, p. 31; Zwitzer Reference Zwitzer1991, pp. 175–6). These soldiers had to be paid and provisioned over long distances. The great strains this posed on state finances, and the potentially dangerous consequences for the economies that carried the burden, did not escape contemporaries. In his 1695 An Essay upon Ways and Means of Supplying the War, which went through several reprints in the following years, the mercantilist thinker and staunch Tory Charles Davenant wrote:

For War is quite changed from what it was in the time of our Forefathers; when in a hasty Expedition, and a pitch'd Field, the Matter was decided by Courage, but now the whole Art of War is in a manner reduced to Money; and now-a-days, that Prince, who can best find Money to feed, cloath and pay his Army, not he that has the most Valiant Troops, is surest of Success and Conquest. So that the present Business England is engaged in, will chiefly depend upon the well contriving and ordering the Ways and Means, by which the Government is to be maintained, and making the publick Charge easie and supportable. (Davenant [Reference Davenant1695] 1701, pp. 26–7)

The large literature on the impact of the Nine Years’ War (1688–97) and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14) on English state finances concentrates heavily on the successes of this state in solidifying the structures for raising revenue and acquiring funds through long-term loans. Ever since Peter Dickson's classic 1967 study, it has been acknowledged that the substantial changes in state finances amounted to a ‘financial revolution’, the most important result of which was to diminish the state's reliance on costly and volatile short-term borrowing by the creation of a consolidated long-term debt under Parliament's control (Dickson Reference Dickson1967; Roseveare Reference Roseveare1991). In an influential article, Douglass North and Barry Weingast argued that the financial revolution established ‘credible commitment’, which they saw as the key institutional factor driving down public and private interest rates, laying the basis for the growth of financial markets and even for the Industrial Revolution later in the eighteenth century (North and Weingast Reference North and Weingast1989). Many later authors have either questioned or nuanced the direct and positive links drawn by North and Weingast between political regimes and interest rates, between interest rates on public loans and private loans, and between the Glorious Revolution, economic growth, and the Industrial Revolution (Clark Reference Clark1996; Quinn Reference Quinn2001; Sussman and Yafeh Reference Sussman and Yafeh2006; Temin and Voth Reference Temin and Voth2008; Coffman, Leonard and Neal Reference Coffman, Leonard and Neal2013). To such criticisms that draw primarily on evidence on the functioning of markets for government debt and private investment in England itself, Oscar Gelderblom and Joost Jonker inter alia have added the example of Holland's public debt. Here, they argue, credible commitment developed gradually and from the ground up without a moment equivalent to the Glorious Revolution, and without a sudden major shift from short-term to long-term debt (Gelderblom and Jonker Reference Gelderblom and Jonker2011; also see Tracy Reference Tracy1985; ’t Hart Reference ’t Hart, ’t Hart, Jonker and Van Zanden1997, Reference ’t Hart2014, ch. 7; Fritschy Reference Fritschy2003).

This article contributes to the existing literature by exploring a neglected dimension of war finance, that is, the crucial role that reliance on merchant networks and financial intermediaries continued to play in international troop payments arranged by both the English and the Dutch states. Even when the English or Dutch treasuries could find the necessary money to pay and provision their troops in time – which, despite their respective financial revolutions, was by no means always the case – getting the money to the military commanders in the field or to their distant suppliers often depended on long and complex credit lines. Payments to the army had to be organised across great distances, with sufficient regularity to prevent mutiny, and in denominations small enough to be used by soldiers in local transactions. Short-term loans acquired in making military expenditure – consisting of unpaid bills to suppliers, payments advanced by officials and officers, temporary loans contracted by financial intermediaries – as well as the widespread reliance on commercial credit in the form of bills of exchange as a way to transfer funds effectively formed the life thread of army finance. However, the paucity of sources and the overwhelming focus in the historiography on increasing state revenues has largely caused this crucial aspect of state finance to be neglected. Furthermore, the often messy and difficult-to-trace operations of the paymasters organising these credit flows from the early modern period onwards gave them the reputation of being corrupt and rent-seeking. By examining the operations of James Brydges, the English Paymaster-General during the later phases of the War of the Spanish Succession, as well as the networks of merchants, bankers, and a specialised group of financial intermediaries in troop payments called solliciteurs-militair (military solicitors) that he drew on in the Dutch Republic, this article will provide details on the practical side of managing the massive funds required for paying the army. Doing so relied directly on the state's ability to tap into pre-existing private flows of commerce and credit. Connecting the archives of the English Paymaster-General with the records of Dutch financial intermediaries involved in troop payments gives a much more complete picture of the interplay between state and financial capital in this important state task than can be obtained through studying relations between England's national debt and London's financial markets alone.

I

D. W. Jones has calculated the flow of remittances from the English treasury to the troops during the Nine Years’ War and the War of the Spanish Succession, directed towards the Southern Netherlands, Castile and Portugal. These were comparable to the wartime expenses on soldiers’ pay of the Dutch Republic, which overwhelmingly flowed towards the same theatres of war. As Table 1 shows, at the peaks of both wars English and Dutch troop payments stood at roughly similar levels, but total Dutch expenses on troop payments around the turn of the eighteenth century still surpassed those of the English state.

Table 1. English and Dutch remittances to troops, 1689–97 and 1702–12

a Including loans raised for foreign powers on the London capital market.

b 1688–9.

c 1689–90.

d 1690–1.

e These amounts are ex ante, projecting future expenditure rather than noting actual expenses. Totals calculated on the basis of army expenditures consented to by the Province of Holland. Yearly exchange rates provided by Denzel 2010, pp. 66–7.

f No exchange rate available for this year.

Sources: Jones Reference Jones1988, p. 38, HaNA, States General, 1.01.02, nos. 8103-21, 8130-53, ‘Staten van Oorlog’.

Since at least Dickson's famous work on the ‘financial revolution’, strong emphasis has been put on the way in which the English state managed to overcome its perennial problems of wartime financing by introducing a whole spectrum of new instruments for raising long-term loans at gradually diminishing interest rates. Total debt increased from roughly £3.3 m in 1692, all of which was unfunded and short term, to £34.9 m in 1712, of which £9.3 m was unfunded and short term (Carruthers Reference Carruthers1996, p. 80; Dickson Reference Dickson1967, Appendix C). In the first years after the Glorious Revolution, William III still turned to the time-tested means of short-term borrowing in the form of promissory notes or tallies, at interest rates of between 5 and 8 per cent (Murphy Reference Murphy2009, pp. 39–40). The main change brought about by the Glorious Revolution was that these short-term loans were now not secured by the Crown but by Parliament, thereby ‘nationalising’ the debt (Braddick Reference Braddick1996, p. 42). During a period of intense experimentation with new financial instruments in the course of the Nine Years’ War, increasing tax revenues were used to gradually replace such unreliable and expensive short-term loans with new forms of long-term debt. The most innovative of those were the loans of £1.2 m raised through the Bank of England in 1694 and of £2 m raised through the New East India Company in 1698, where private companies took on part of the state debt by issuing stock easily tradable on the secondary market. This approach was followed again on an even larger scale during the War of the Spanish Succession, with the conversion of single-life annuities into 99-year annuities, the doubling of the capital stock of the Bank of England in 1709, and then most spectacularly with the founding of the South Sea Company in 1711. The latter bought up over £9 m worth of outstanding long-term and short-term debt at a reduced interest rate of 5.5 per cent using money raised by issuing stock, on the promise of obtaining the slave trade asiento from the Spanish Crown (Carlos et al. Reference Carlos, Fletcher, Neal, Wandschneider, Coffman, Leonard and Neal2013, pp. 152–3).

The financial revolution did much to solidify the basis for paying the army. But it did not do miracles. As the figures quoted earlier indicate, despite the introduction of a series of new instruments for creating long-term funded debt, about a quarter of the outstanding debt at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession remained short term and unfunded. In absolute terms the amount of floating short-term debt had almost tripled since 1692. Tallies that sold at heavily discounted rates continued to play an important role in emergency finance. What especially the issue of South Sea Company stock in 1711 did was to put a break on the downward slide of the rate at which this short-term paper was accepted and to provide financiers of the state with a new range of options for raising money quickly. This can be seen from the accounts of Paymaster-General James Brydges, preserved as part of the Stowe Manuscripts at the Huntington Library in San Marino (California). James Brydges succeeded Paymaster-General Stephen Fox in 1705, being handed responsibility for all troop payments in the Southern Netherlands and Portugal. His biographers sum up his achievement, if one can call it that, as ‘a swift rise from the mediocrity of an obscure heir of a small, impoverished estate in Herefordshire to the stature of the most successful war-profiteer in that age’ (Baker and Baker Reference Baker and Baker1949, p. xi). English paymasters executed their task in exchange for a ‘poundage’, the right to extract one shilling in every pound from all army pay passing through their hands, but they could also gain considerable sums on arbitrage, advancing personal funds to the state, speculating on changes in exchange rates in international transfers, and underhandedly buying up state paper for their own account at large discounts. Brydges’ spectacular economic rise during the War of the Spanish Succession, bringing him private gain estimated at as much as £600,000 to £700,000, has traditionally been ascribed to the intensely corrupt way in which he handled troop remittances (Baker and Baker Reference Baker and Baker1949, p. 51). However, more recently, Aaron Graham has pointed out that Brydges’ acumen in playing financial markets in England and the Netherlands – while certainly not free of large-scale corruption – did alleviate the serious problems that had plagued English troop payments during the early years of the war (Graham Reference Graham2015).

In the run-up to the ‘debt for equity swap’ through the founding of the South Sea Company, the sale of tallies by Brydges still formed an important instrument for raising ready money, but with rapidly increasing difficulties. On 6 February 1711, Brydges wrote to thank his partners in the Dutch Republic Drummond & Van der Heyden for accepting two bills of exchange for 76,500 guilders (about £7,500 in pounds current),Footnote 1 but at the same time complained that the London bankers who had issued the bills had only accepted tallies for payment at incredible discount rates:

I return you many thanks for the favour you have done me in this negociation, tho the Tallies wch were directed by the Cnstble the Ld of the Treasury for discharging of those bills, carry such a discount as will make me a considerable loser by the business, wch shall be a warning to me for the future never to engage again in any transaction of the like kind.Footnote 2

From July 1711 onwards, the issuing of South Sea Company stock greatly improved Brydges’ financial room for manoeuvring. Showing his confidence in the market, Brydges, through the London bankers Hart and La Marye, purchased around £70,000 worth of stock for his own account, as well as ‘refusals’ or call options that would give him the right to buy over £90,000 more, speculating on future price rises (Graham Reference Graham2015, p. 193).

The financial revolution was without a doubt an important factor in England's success in the War of the Spanish Succession. While it still borrowed at higher interest rates than the Dutch, who even at the peak of the financial strains in the final years of the War of the Spanish Succession often managed to obtain short-term loans at 4–5.5 per cent, it certainly fared better than the French monarchy, which spiralled into financial chaos as the war progressed (Rowlands Reference Rowlands2012; see also Félix's contribution in this issue). However, obtaining funds for the treasury was not the only financial challenge the state faced. Transferring these funds to soldiers fighting distant wars, and doing so with the regularity required to prevent starvation or mutiny, was a different story altogether.

II

Stable income for the state through a wide variety of sources and in instruments that were easily tradable on the secondary market was a key requirement for acquiring the necessary funds, but it was not in itself sufficient for making sure payments continued to arrive at their destination in time. The remainder of this article will show how, not only in gathering funds but also in the process of expenditure itself, the state depended on complex dealings with the market. The key official within the English system of troop payments was the Paymaster-General, appointed directly by the Crown and falling under Parliamentary control. On the ground, the Paymaster-General was assisted by deputy paymasters, who were stationed in the countries where payment took place. Beneath this official structure, there developed networks of regimental agents, employed by the officers in order to assist in managing their financial affairs. However, the operations of these agents remained limited compared with those of the Paymaster-General, who was the real organiser and largest private beneficiary of army-related financial flows (Childs Reference Childs1987, pp. 139–43). From 1694 onwards, paymasters could draw the funds needed to pay the troops directly through exchequer bills issued by the Bank of England. The Paymaster-General would use the credit thus created to buy foreign bills of exchange from London merchants and bankers. These could in turn be used to draw on commercial credit abroad.

The reason for the Paymaster-General's dependence on this instrument was that the main alternative, sending payments directly to the deputy paymaster in the form of shipments of specie, was generally too risky, costly and impracticable to contemplate. Furthermore, the need to locally convert bullion into the small-denomination coins required for paying soldiers’ wages created another layer of difficulties, as well as opportunities for large-scale embezzlement and fraud. Only in cases where soldiers were stationed close to where money in coin was obtained, or, inversely, where no commercial networks existed that could supply the necessary funds, did paymasters reluctantly revert to this option (Jones Reference Jones1988, pp. 77–8 and 87–8; Brandon Reference Brandon2015, pp. 241–4). As early as the sixteenth century rulers had preferred to transport funds by means of commercial bills of exchange, or by locally contracted short-term loans (Parker Reference Parker1972, pp. 146–8). With the growth of international trade and credit flows, the relative attraction of these options increased.

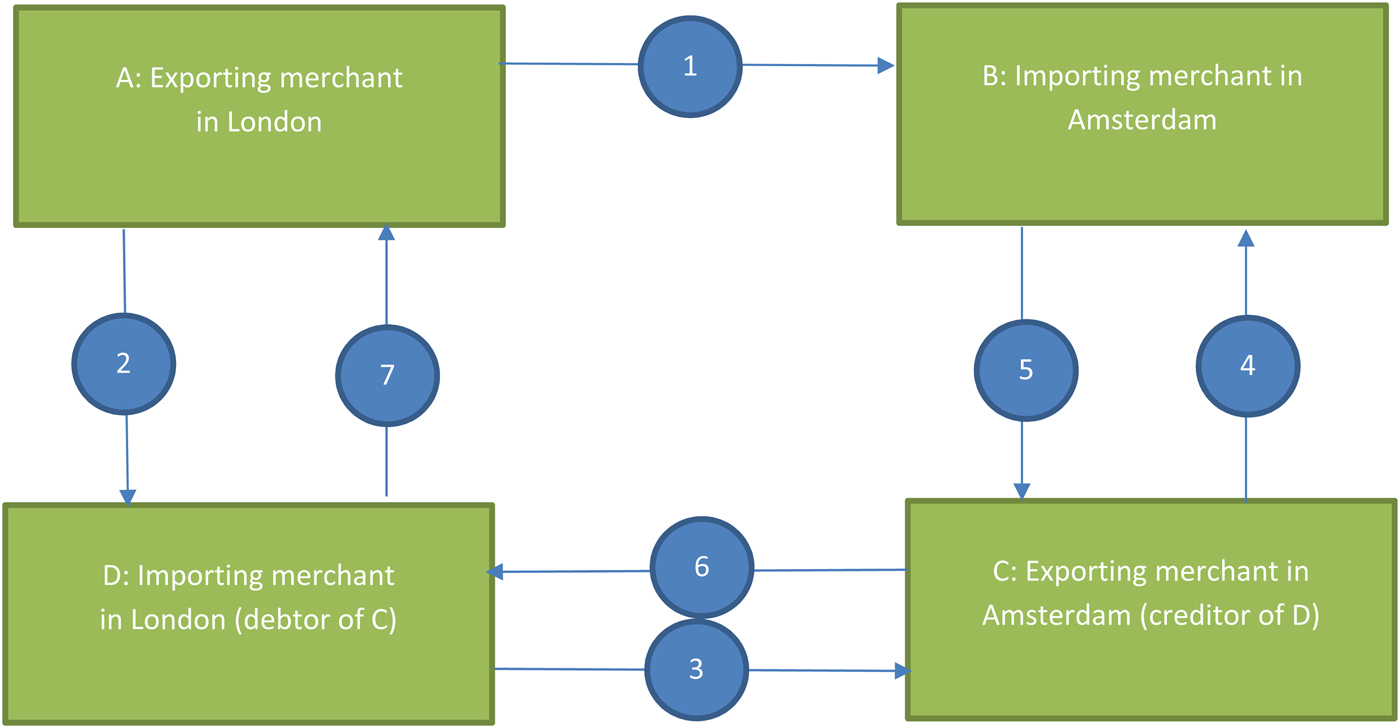

Even though the underlying premises are relatively simple, the practice of arranging international troop payments by drawing on outstanding commercial credit through bills of exchange was dazzlingly complicated and non-transparent.Footnote 3 Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of the ordinary use of the bill of exchange to settle commercial accounts between four merchants: a London merchant A who exports goods to Amsterdam where they are bought by merchant B, and an Amsterdam merchant C who exports goods to London where they are bought by merchant D. Supposing that merchant C has already sold goods to merchant D at the same value at which merchant A wants to sell to B, the Amsterdam merchant B can settle his resulting debts to London merchant A by paying off the debts of the London importer D to his Amsterdam exporter, asking the London merchant to do the same. In this way, accounts can be balanced without any need for remittances in specie across the Channel. However, this ability to balance accounts without the intermediation of money pertains only as long as there is no structural imbalance between imports and exports. If, as was the case in the period under discussion, Dutch merchants structurally import more goods from England than vice versa and England thus holds a permanent surplus on the balance of trade, this requires an accompanying flow of bullion in addition to the flow of bills of exchange to settle the debts. This undesirable state of affairs, however, could be avoided, and indeed was avoided in practice. Since England was a net importer from northern Europe and France, English merchants could use at least part of their credit in Amsterdam to settle accounts for their trade on other European nations. Using the figures collected by David Ormrod, Table 2 shows the potential for acting in this way created by the sizeable surplus on the balance of trade that continued to exist throughout the War of the Spanish Succession.

Figure 1. Schematic presentation of the settling of commercial accounts between exporting London merchant A and importing Amsterdam merchant B, using the credit of importing London merchant D for exporting Amsterdam merchant C by bill of exchange (BoE)

Table 2. English trade balance with Holland (× £1,000)

Source: Ormrod Reference Ormrod2003, p. 356, for import and export figures.

If traders from other nations could draw on surpluses of commercial credit in Amsterdam, so too could the Paymaster-General in England in order to transfer money to the troops. The final column in Table 2 gives troop remittances to the Southern Netherlands as a proportion of the trade surplus, where a proportion of 1 would signify that the entire trade surplus would be used to pay the army there. For the sake of clarification, Figure 2 presents a schematic representation of the use of bills of exchange similar to Figure 1, but this time introducing a situation in which the London merchant A exports £12,000 worth of goods but London merchant D imports the equivalent of only £4,000, thereby leaving £8,000 as credit in the hands of merchant B in Amsterdam. It then shows how the Paymaster-General could draw on this merchant's credit to pay the army in the Southern Netherlands. The same system was of course also used to draw on credit in other important commercial centres near the main theatres of war. But given the significance that the Dutch Republic still had in European commerce at the time, Amsterdam merchant houses were exceptionally well suited for such financial operations (van Bochove Reference Van Bochove2008).

Figure 2 Schematic presentation of the settling of commercial accounts between exporting London merchant A and importing Amsterdam merchant B, where the credit in the hands of importing London merchant D for exporting Amsterdam merchant C is insufficient to offset the debts of C, and the Paymaster-General uses the surplus on the London balance of trade to arrange for the army to be paid through Amsterdam

Alice Carter, D. W. Jones, and Larry Neal and Stephen Quinn have presented important case studies showing how English paymasters used the networks for handling bills of exchange of large goldsmith bankers such as Edward Backwell, of Huguenot and Jewish financiers in London such as Theodore Janssens and Moses Hart, and of prominent London City bankers such as Edward Gibbon, Sir John Lambert and Sir Richard Hoare to make transfers to Amsterdam and the other financial centres of Europe (Neal and Quinn Reference Neal, Quinn, Engerman, Hoffman, Rosenthal and Sokoloff2003; Carter Reference Carter1975, pp. 81–2; Jones Reference Jones1988, pp. 84–6). However, these accounts by and large present only the English side of the story. The assumption seems to be that, given the wealth of the Dutch Republic and the size of the English trade surpluses, the ability to draw on credit there was more or less self-evident. However, this can be questioned. The surpluses that the Paymaster-General tried to draw on were not concentrated, but existed in the hands of many traders. Drawings on their accounts came in leaps and bounds that did not necessarily run parallel to their trading operations. Effectively, this often made the bill of exchange itself a credit instrument, drawing advances on future trade imbalances rather than settling existing imbalances (Michie Reference Michie1998, pp. 8–9). Furthermore, drafts for military purposes competed with other claims arising from the needs of foreign trade, or from the continuing quest for funds by the Dutch state. Practical problems were created by the fact that these traders were situated in Amsterdam (or Antwerp, Genoa, Naples, or Hamburg, for that matter), far removed from the frontlines that military expenditure had to be directed to. Finally, while the English state had greatly improved its ability to acquire funds, the timing often still lagged behind the exigencies at the front, enticing English paymasters to make considerable overdrafts on their Dutch partners. In such a situation in which funds have to be drawn from many sources under time pressure, financial intermediation attains an important role (Kuznets Reference Kuznets1961, pp. 22 and 31; Engerman et al. Reference Engerman, Hoffman, Rosenthal and Sokoloff2003). Costs of 4 per cent or lower seem not to have been uncommon for transactions arranged in the Dutch Republic, and such costs only rarely exceeded 5 to 6 per cent, while in England costs were still considerably higher. Where intermediation was weak, trade was lacking, exchange rates were volatile, or money was scarce, the costs of organising transactions through bills of exchange could become prohibitive. Thus, in the later phases of the War of the Spanish Succession, the French treasury paid 8 to 9 per cent in transaction costs simply for transferring funds internally, between Paris and Strasbourg, and bills on Lille were discounted around 4 per cent (Rowlands Reference Rowlands2011, p. 511). By adding the Dutch side of the picture, it becomes clearer how personal networks centring on the heart of European financial capitalism aided military finance.

III

Brydges’ account books and substantial correspondence can be used to gain insight into the large network of intermediaries employed in sending money to the troops in the Southern Netherlands. Intermediation began in England, where financiers with strong Dutch connections, such as the Tory merchant banker of Dutch origins Matthew Decker, allowed Brydges to draw bills of exchange issued to their business associates in the Netherlands. These were located primarily in Amsterdam, where ‘the greater part of the remittances must still be made’.Footnote 4 In the Netherlands, Brydges then employed the services of the deputy paymasters Benjamin Sweet and Henry Cartwright, who were based in the Southern Netherlands, the Rotterdam merchants Jacob and Walter Senserf and Abraham Romswinckel, the military solicitor Johan Hallungius, the Anglo-Dutch trading company Drummond & Van der Heyden, and towards the end of the war also increasingly the powerful merchant banker Andries Pels (Jonckheere Reference Jonckheere2008). Soon after accepting the position of Paymaster-General, Brydges travelled to the Dutch Republic in order to establish his overseas connections for his business in the Low Countries (Baker and Baker Reference Baker and Baker1949, pp. 44–5). Already from the time of this visit, there is evidence in his letters of an intense competition between Brydges and his deputy paymaster Benjamin Sweet.Footnote 5 Each of them tried to organise remittances through their respective networks of private intermediaries, ostensibly to increase their personal control over the flow of funds, and to reap larger rewards. Brydges actively used his position to advance two of his clients, the military solicitor Johan Hallungius and the merchant diplomat John Drummond, as financial agents for individual regiments that used to be served by Sweet.Footnote 6 In 1711, he even launched a campaign to allow Drummond to replace Sweet and Cartwright as deputy paymasters. However, just when he had almost succeeded, the bankruptcy of another intermediary in troop payments, Stratford, caused the collapse of the firm of Drummond & Van der Heyden (Hatton Reference Coffman, Leonard and Neal1970, pp. 84–5). According to Senserf, in negotiating financial affairs on the scale they did, Drummond & Van der Heyden ‘were rising, but out of their sphere’ (quoted in Hatton Reference Hatton, Hatton and Anderson1970, p. 80). Brydges replied:

I am heartily sorry for Messrs van der Heiden & Drummond. I have been for some time afraid of them, but being unwilling to show it to much as to do them any prejudice, I shall by that means become a considerable sufferor by them. The publick will likewise loose a great deal, there being but 20 m£ [m stands for 1,000 – PB] paid of a bill they had accepted for 30 m£.Footnote 7

It seems no coincidence that, as Table 2 shows, 1711 was a year in which the size of remittances to the troops in Flanders in proportion to the English surplus on the balance of trade with Holland was particularly large (close to 1). Given such tight market conditions, the propensity of overdrafts must have greatly increased. It is testimony to the strength of the financial network that Brydges had by then assembled in the Low Countries that the collapse of one of his most important intermediaries did not fundamentally undermine his capacity to continue financing the English troops abroad. Matthew Decker played a pivotal role in keeping afloat his financial operations. Table 3 provides a list of the 17 merchants in the Dutch Republic drawn on to settle a single bill of £2,200 by Matthew Decker in London on 24 November 1712. Involving such a wide network of merchants was the logical by-product of using outstanding commercial debts to settle accounts, but arguably it also diminished the risks of overdrafts that had led to the collapse of Drummond & Van der Heyden.

Table 3. Dutch merchants drawn on to settle a single bill of £2,200 on 24 November 1712

Source: HL – ST, no. 12, ‘Accounts with Brokers, Volume 1’, fol. 72vso.

Another way to diminish risks was to seek the involvement of merchant houses whose credit standing was beyond doubt. In the final stages of the War of the Spanish Succession, and especially after the bankruptcy of Drummond & Van der Heyden, Brydges increasingly came to use the services of Andries Pels, head of one of Amsterdam's richest families, if not the richest in this period. Pels had started out as a large-scale commodity trader with strong cross-channel connections, but during the first quarter of the eighteenth century he used the wealth thus accumulated to launch one of the most successful international banking operations of the eighteenth century. It is noteworthy that some of the main Amsterdam merchant-banking houses of the eighteenth century similarly had their origins in or shortly after the War of the Spanish Succession; Andries Pels & Sons was founded in 1707, the direct predecessor of Muilman & Sons in 1712, and both Hogguer and Hope & Co. around 1720 during the postwar financial boom that ended with the collapse of the South Sea Bubble (Buist Reference Buist1974, p. 5). These houses soon acquired large holdings in English stock, pushing forward the process of financial integration between Amsterdam and London that played a central role in the rise of international financial capitalism (e.g. Wilson Reference Wilson1941; Neal Reference Neal1990). James Brydges made connections to Andries Pels through John Drummond, who described the merchant house of Pels & Sons to him as ‘the most powerful of this place’ (cited in Graham Reference Graham2011, p. 237). Between December 1712 and March 1714, Brydges made transactions whose total value exceeded half a million guilders through Pels's account.Footnote 8 The relative importance of this large-scale banker became even greater in the turbulent postwar period. Pels continued to regularly accept large sums in bills of exchange for Brydges in order to assist in the settling of debts accumulated during the war, such as a bill of £4,900 for Matthew Decker and £3,500 for the Palatine troops in September 1715, and 60,966 guilders for Mr Steinghers the next month.Footnote 9 However, Pels did take precautions in this relationship and did not automatically accept all of Brydges’ bills of exchange. While accepting the latter bill for Steinghers, he refused another bill for 100,000 guilders. Showing the importance of reputation and confidentiality in such credit relations, James Brydges lamented to Matthew Decker:

I was much concern'd to hear by the last Holland Post that the bill of 100 m fl was protested, that which troubles me most in it is, that I fear it will occasion so much talk as may make that transaction come to be known before I would willingly have had it.Footnote 10

Overall, however, Pels remained a trusted connection for handling bills of exchange.

Business contacts did not remain limited to the closing of wartime accounts. Brydges used the fortune he amassed during the War of the Spanish Succession to continue to operate as a large-scale stockbroker, an activity he pursued with mounting success until the collapse of the South Sea Bubble left him with substantial losses. With the Amsterdam and London stock markets becoming increasingly connected, Pels provided Brydges with information on conditions on the Amsterdam market. In the period of intense speculation preceding the bursting of the South Sea Bubble, the quality of information could make or break fortunes. On 8 April 1720, Brydges wrote to Pels thanking him for information on a sudden lowering of South Sea stock in Amsterdam, and asking him for his ‘solid judgement’ on the causes.Footnote 11 A week later, on 15 April 1720, Brydges asked Pels to sell stock at his discretion when it reached 400 points, as well as buying substantial amounts of East India stock.Footnote 12

Given Brydges’ strong connections in British commercial circles, the relationship with Pels was clearly of mutual benefit. Through Brydges, Pels offered to replace the Rotterdam trader W. Senserf as the main representative of the Royal Africa Company on the Dutch market. As we have seen, Senserf himself was a protégé of Brydges from the time of the War of the Spanish Succession. However, by the 1720s Pels had overtaken him in importance as a commercial connection, and so Brydges went out of his way to further his interests in London:

I acquainted the Gentlemen also with yr offer to service them in the buying and selling such Effects as they may have occasion of in Holland & as they are very sensible of the advantage they shall receive by so usefull & generous a Correspondent they are very willing to accept it, as to that part of disposing of the effects they shall sell in Holland and accordingly will ensign to you all such as to their Goods which are to be bought in Holland, that being already well served by W. Senserf of Rotterdam they cannot with decency immediately leave him, but they think it better to divide it accordingly the one half of what they have occasion to buy they'l [honor] you with the Commission.Footnote 13

At the time of this letter, the business connections between Brydges and Pels had already been harmed by the collapse of the South Sea Bubble. Nevertheless, the association between the former English Paymaster-General and major financial speculator Brydges and one of the leading Anglo-Dutch merchant bankers was indicative of the way war finances not only relied on pre-existing cross-Channel commercial and financial connections but could also help to strengthen them, mobilising the wealth of the most prominent financial capitalists of the age in the service of extending state power. However, transferring war-related funds did not involve only the top layer of international financiers and large commercial houses in London and Amsterdam. Crucial tasks in the day-to-day management of funds between the Dutch Republic and the Southern Netherlands were executed by financial intermediaries of much more modest means.

IV

Whereas in the more centralised English system of troop payments the Paymaster-General and his local deputies fulfilled important tasks in overcoming practical difficulties in raising and transferring money, the decentralised Dutch Republic ‘outsourced’ many of these tasks to a group of financial intermediaries – military solicitors – specialised in handling payment ordinances. Apart from organising money transfers through bills of exchange in more or less the same way that we have previously seen James Brydges engaging in, they also played an important role in raising short-term credit either through their own funds or through the market to keep the funds flowing in cases of arrears. In the Dutch Republic, each of the seven provinces retained authority over the payment of ‘their own’ regiments. The provincial treasurer was responsible for issuing and eventually paying the ordinances. However, the practical organisation of getting money from the treasury to the soldiers was left completely in the hands of the military solicitors. As one seventeenth-century observer acknowledged, ‘those military solicitors are driven by the hope of a large and secure profit’ (Boxhorn Reference Boxhorn1674, pp. 63–4). The captains had to pay the solicitors a salary out of the money they received from the provinces, and above this sum the solicitors received interest over the money they advanced. Especially in times of war, the interest payments could far surpass the salaries paid to the agent. Not only for troop payments, but also for the handling of many other types of contract (such as deliveries of bread, oats, and wagons), the state relied heavily on the private credit networks of the military solicitors. By the end of the seventeenth century, most soliciting contracts were concentrated in the hands of about 30 financial specialists with strong contacts with banking families (Brandon Reference Brandon, Conway and Torres2011). The solicitors provided an essential network for transactions and loans on the ground, reaching from Amsterdam to the cities near the frontlines in the Southern Netherlands.

Assisting in money transfers that far exceeded the modest means of the military solicitors themselves implied direct personal relationships with both state officials and bankers. This can be seen from the records left by Paulus Gebhardt, who entered the service of Willem van Schuylenburg, accountant of the Nassau Domain Council and one of the central financial officials within the stadtholder's Dutch entourage, just before or just after the Glorious Revolution (Onnekink Reference Onnekink2007, pp. 88 and 101). At that time van Schuylenburg was involved in financing the recruitment of troops from Brandenburg, Cell and Wolffenbüttel, Hessen-Kassel, and Würtemberg for William's 1688 campaign, transferring some 800,000 guilders from the treasury of Receiver-General van Ellemeet to the German allies.Footnote 14 After William of Orange's accession to the English throne, these troops became jointly financed by the Dutch and English treasuries. Between 1689 and 1692, van Schuylenburg acted as paymaster of the British troops in the Southern Netherlands, and after that he continued to play an important role in securing loans for the British Crown on the Dutch capital markets. As van Schuylenburg's clerk, Gebhardt was given responsibility for paying a large number of regiments. From 1689 onwards he fulfilled all the functions of a military solicitor, executing his tasks essentially as an independent business for his own profit. He continued to do so in the service of van Schuylenburg until the mid 1690s.Footnote 15 On 22 March 1695 he was granted permission to act as a solicitor in his own right for the province of Groningen.Footnote 16 Admission as a solicitor by the Holland provincial government followed a year later.Footnote 17 His employment by Willem van Schuylenburg allowed Gebhardt to enter the business of solicitor on a grand scale. By 1689 he already served 30 companies.Footnote 18 By 1695 the number had grown to ten complete regiments and 23 companies. In total, Gebhardt had to supply these troops with an annual salary totalling almost 1.5 million guilders.Footnote 19

Only with strong creditor networks of their own could military solicitors execute financial tasks on this scale. Central to Gebhardt's financial connections were a number of very large financiers. The most prominent during the first years was Willem van Schuylenburg himself, who not only acted as Gebhardt's employer and as paymaster to the subsidy troops of the British Crown but also provided Gebhardt with large amounts of credit. But van Schuylenburg's ability to do so was not limitless. There is some evidence that around the mid 1690s the serious strains on the finances of the British Crown had detrimental effects on van Schuylenburg's own financial position. In January 1697 the Duke of Portland warned the British paymaster Richard Hill, who was then in Brussels in order to supervise troop payments, that he should not expect to receive ready money from van Schuylenburg, who ‘has suffered such a great failure of his credit and such large losses that I believe that he will have great trouble to remit [his bills of exchange – PB] for a long time’.Footnote 20

Although van Schuylenburg remained one of Gebhardt's principal creditors until the early years of the War of the Spanish Succession, his central place in Gebhardt's financial network was gradually assumed by the Amsterdam merchants and bankers George and Isaac Clifford. By the mid 1690s, they were negotiating over 900,000 guilders for Gebhardt in a single year. The choice of Clifford seems logical. At this time Clifford & Co. was gradually establishing itself as one of the major Dutch merchant banking houses (Jonker and Sluyterman Reference Jonker and Sluyterman2000, pp. 94–5). Its prominence was mostly due to its strong connections across the Channel. In 1695 George Clifford helped to transfer 2 million guilders from the Bank of England to the Netherlands for troop payments. A substantial part of this sum, amounting to 1,265,300 guilders in the short period between 30 August and 25 October 1696, went through Gebhardt's account.Footnote 21

However, Gebhardt's dealings with Clifford & Co. sharply declined after 1703. This reflected a more general decline in his business that can be observed from the distribution of Gebhardt's accounts in his ledgers. In 1695 and in 1703, Gebhardt dealt with over 40 clients, and with eight of those the volume of financial transactions exceeded 100,000 guilders annually. By 1704 these numbers had dropped to 24 and one, and by the end of the war in 1714 to eight and zero respectively.Footnote 22 The cause of Gebhardt's marginalisation just as the War of the Spanish Succession was taking off was, in all likelihood, political. The death of William III in the spring of 1702 created serious diplomatic fallout. On 17 May 1702, the King of Prussia laid claim to William's Dutch inheritance, leading to prolonged conflict between the States General and William's Dutch heirs (Bruggeman Reference Bruggeman2007, pp. 205–7). The resulting deterioration in relationships between the Republic and a number of German allies led to the termination or renegotiation of a large number of troop contracts. Gebhardt was kept out of all new contracts. By 29 July 1703 he had ended his engagement with most of his former clientele, remaining military solicitor on a much more modest scale. The ‘special relationship’ with one of William III's key financial officers seemed to have been both the root of his success and of its undoing.

Unfortunately, not much is known about the military solicitors with whom Brydges dealt during the later phase of the War of the Spanish Succession, such as Hallungius. However, many archival records exist for another solicitor who was heavily involved in providing financial services to the English troops as well as the Dutch, Hendrik van Heteren III. Van Heteren initially became a solicitor through his political connections. His father and grandfather (Hendrik I and Hendrik II) had slowly worked themselves up from initially low-ranking positions at the offices of the States of Holland and the Receiver-General (Knevel Reference Knevel2001, pp. 109–10). It was the War of the Spanish Succession that laid the foundation of Hendrik III's rise to prominence. He had already acted as financial agent for a select group of diplomats in the service of the Republic before the start of the war.Footnote 23 The outbreak of hostilities allowed him to expand his clientele. Among his newly acquired clients were Field Marshal Hendrik van Nassau-Ouwerkerk, Lieutenant General Tilly, Quartermaster General Pieter Mongeij and Wagon Master General Zuerius.Footnote 24 Many of these contracts carried over into continued financial services after the end of the war, and his strong network also allowed van Heteren to acquire new clients. Van Heteren became an important intermediary in handling contracts related to the maintenance of Dutch fortresses. For example, in 1727 he handled the finances for the acquisition of palisades for the upkeep of fortresses in the east of the Republic; the palisades were valued at 117,187 guilders.Footnote 25 He also ventured outside the confines of military-related financial intermediation, investing in VOC (Dutch East India Company, Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie) stock and a Suriname slave plantation as well as handling the financial affairs of several Dutch diplomats. From each of his contracts, van Heteren drew an income consisting sometimes of a salary, sometimes of interest on advances or charges on transactions, and often a combination of all three.

Van Heteren's largest contract by far was for the ‘soliciting’ of oats and hay. Between 1706 and 1711, van Heteren handled contracts worth over 4 million guilders.Footnote 26 These were divided among several subcontractors, of whom Zeger Gorisz, Jacques Meyers, Pieter Pangaert, Martinus Robijns and Henry Francois Heymans received the most substantial sums. These large-scale suppliers operated in the Southern Netherlands on behalf of both the States’ army and English subsidy troops, often working in partnership. Van Heteren handled their payment ordinances at a charge of 1 per cent, but he also advanced large sums to cover arrears. In the process, he dealt with dozens of other military solicitors and local financial agents. This large private network became all the more indispensable as the war dragged on into the 1710s. The last years of the War of the Spanish Succession left a legacy of an enormous pile of unpaid bills. On 17 July 1713, fodder contractor Robijns complained about the unwillingness of English regiments to pay for past supplies.Footnote 27 In a follow-up letter two weeks later, he even aired his suspicion that ‘deceit and conflict’ were behind the slowness in settling accounts, mentioning Hallungius – the military solicitor and client of James Brydges – as one of the culprits.Footnote 28

These payment problems were not confined to English regiments. Especially in the last phase of the war, the States General started to use a wide variety of short-term and long-term loans to pay their contractors, often at interest rates of 5 per cent or more. In doing so, they frequently reverted to the older practice of promising creditors a share in specific streams of tax revenue. Table 4 shows a list of bonds received by van Heteren to pay fodder contractor Zeger Gorisz which were drawn not only on the States General and the Holland Northern Quarter, but also on the income of the Southern Netherlands Post Office and the Southern Netherlands custom-collecting fortresses.

Table 4 Bonds transferred by Hendrik van Heteren in lieu of payment to Zeger Gorisz, contractor for fodder magazines, 1707–11

Source: HaNA, van Heteren, 3.20.34/no. 118, Account Zeger Gorisz.

The accounts with fodder contractors were not settled until many years after the war, and in some cases only after many decades. For smaller contractors, this could lead to financial collapse. But for those with sufficient funds, the outstanding debts of the state, especially when renegotiated into longer-term and reliable bond portfolios, could also be a continued source of profit. Between 1719 and 1727, Hendrik van Heteren paid out over 150,000 guilders in interest to Martinus Robijns for his unpaid fodder contracts.Footnote 29 As long as the state eventually honoured its commitments, both large-scale contractors and the better placed among their intermediaries could financially weather the storm of peace.

Like these dealings by Gebhardt and van Heteren, the accounts and letters of Brydges during the War of the Spanish Succession testify to the fact that the large and concentrated streams of funds required by the troops were often pieced together by meticulous strings of bills drawing on existing credit or creating new debts left and right. The seemingly chaotic nature of these transactions, and the many opportunities for speculation on interest rates, the underhand buying and selling of discounted bills for their own account, and insider dealing by officials in close collusion with their intermediaries gave war finances the not unjustified reputation of being a cesspool of corruption and rent-seeking. However, the wide network of local intermediaries that existed in the Dutch Republic, and the great wealth they could draw on, also ensured that money continued to flow at interest rates or discounts that remained within bounds. In the summer of 1712, after years of mounting costs in the field, Walcot, a financial intermediary in The Hague, could assure Brydges that ‘there are people enough [to] solicit very earnestly for Paymts of Ext[traordinar]ys’.Footnote 30 Using the outstanding claims of English traders on the Dutch Republic, the financial networks of London and Amsterdam bankers, large and small Dutch merchant houses, and the on-the-ground intermediation of military solicitors, the English Paymaster-General could thus continue to transform commercial wealth into military might.

V

By the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, both English and Dutch state debt had grown to unprecedented levels. A quarter of a century of near uninterrupted warfare, in which at the peak both states maintained over 100,000 soldiers in the field in the Southern Netherlands and on the Iberian Peninsula, had laid great claims on their respective treasuries. The substantial literature on the financial revolution in England, going back to Dickson's classic work on the subject, shows how following the Glorious Revolution of 1688 the English state overcame its problems by a string of innovations that increased its ability to attract long-term loans. While outstanding short-term debt as a proportion of English state debt as a whole diminished as a result of the financial revolution, this article has shown how substantial amounts of short-term debt continued to be accrued in the form of unpaid bills to suppliers, payments advanced by officials and officers, temporary loans contracted by financial intermediaries, as well as drafts on commercial credit in the form of bills of exchange used to transfer funds. This was unavoidable, given that money raised by the treasury in England to pay for the troops still had to reach the soldiers fighting on distant front lines. During the Nine Years’ War, Charles Davenant, the same mercantilist thinker who argued that ‘the whole art of war is reduced to money’, also attested that ‘[n]othing dreins a Country so much as a Foreign War, where the Troops must be paid abroad’ (Davenant Reference Davenant1698, p. 101). Examining the day-to-day dependence of the English Paymaster-General James Brydges on financial intermediaries in the Dutch Republic for transferring the immense sums involved in payments to the troops in the Southern Netherlands, this article has shown how the ability to quickly raise short-term credit through the personal networks of traders, bankers and military solicitors, combined with the possibility to transfer funds already raised through the extensive use of commercial bills of exchange, helped to keep the costs of this potentially sprawling area of state expenditure in check. In doing so, James Brydges could make use of the same financial infrastructure that helped the Dutch Republic to pay for its troops at relatively low costs. While other states relied on similar means for the transfer of military funds, weaker commercial and financial connections than those existing between London and Amsterdam could drive up transaction costs to crippling levels. The fact that English and Dutch state officials and their intermediaries operated at the heart of international financial capitalism seems to have been more important to their day-to-day operations than a particular set of institutional arrangements.