1. Introduction

In our globalized world, the ability to communicate effectively with people from different cultures is vital, meaning that second language (L2) learners need to acquire appropriate intercultural communication skills. Byram (Reference Byram1997) advocates for including intercultural communicative competence (ICC) within formal foreign language instruction, as learners need to be not only linguistically competent but also able to negotiate for meaning in different sociocultural contexts.

This study aims to fill research gaps in the field of telecollaboration regarding interactions between EFL adolescent learners from different countries. We chose this age as the period of transition from childhood to adulthood, when adolescents form their opinions and philosophy of life and prepare to face future challenges such as employment and social integration. The students who are the focus of this study are in Spain and Bulgaria, countries where the potential of telecollaboration for language learning purposes is clear because, outside cities like Barcelona or touristic sites, EFL learners hardly ever have the opportunity to practice English in everyday life unless via internet surfing or video gaming. Consequently, students often have trouble communicating in English, even after several years of study, and, as one of our participating teachers said, it is essential “to create opportunities for learners to communicate with native speakers or other speakers of the language in order to acquire real-life experience of using English.” Telecollaboration facilitates such opportunities and so our interest in this study is to explore the interactions among secondary school learners of English during telecollaborative interactions for educational purposes. Section 2 presents a review of literature on telecollaborative interactions, interactional strategies, and empirical research, as well as the research questions. The design and methods used to investigate the issues in question are described in Section 3. The results of the study are presented in Section 4 and discussed in Section 5 and, finally, conclusions are offered in Section 6.

2. Literature review: Telecollaborative interactions and interactional strategies in intercultural learning projects

In the past decades, there has been a rise in research that has examined telecollaboration for educational purposes (Clavel-Arroitia & Pennock-Speck, Reference Clavel-Arroitia and Pennock-Speck2015; Helm, Reference Helm2015; O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2003; van der Zwaard & Bannink, Reference van der Zwaard and Bannink2019; Ware, Reference Ware2013; Ware & Kessler, Reference Ware and Kessler2016). These studies have investigated different aspects of telecollaboration, focusing on student and teacher satisfaction, task design, negotiation of meaning, challenges and factors for successful collaborations, among many others. As for the most recent research, Jakonen, Dooly and Balaman (Reference Jakonen, Dooly and Balaman2022) present studies exploring social interaction in L2 educational environments mediated by technology (Balaman & Sert, Reference Balaman and Sert2017; Jakonen & Jauni, Reference Jakonen and Jauni2021; Rusk, Reference Rusk2019; Tudini & Dooly, Reference Tudini and Dooly2021). Dooly (Reference Dooly, Masats and Nussbaum2021) looked into young learners’ awareness and use of interactional “repertoires” in a telecollaborative exchange, demonstrating that teachers can use computer mediated communication (CMC) to stimulate engagement or to ensure repetition of formulaic language. She found that CMC allows for opportunities to learn and practice mediation strategies during interactional breakdowns. Balaman (Reference Balaman2021) explored the interactional organization of collaborative writing, revealing that repair organization is fundamental for this practice and shedding light on the complex environment of video-mediated interactions in L2 writing.

Numerous studies have also documented the complexities and challenges in the organization and implementation of such educational telecollaborative projects (Balaman & Doehler, Reference Balaman and Doehler2021; Hauck & Youngs, Reference Hauck and Youngs2008; Helm, Reference Helm2015; O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd, Belz and Thorne2006, Reference O’Dowd2013; O’Dowd & Ritter, Reference O’Dowd and Ritter2006). In a recent study, Nishio and Nakatsugawa (Reference Nishio and Nakatsugawa2020) analyzed tensions that emerged during a six-week telecollaborative project between American learners of Japanese and Japanese learners of English through their understandings of successful participation. The authors revealed that the concept of successful participation is context dependent and learners have different definitions of it, which can lead to tension in the manner of participation and also affect other aspects of the interaction.

Ghazal, Al-Samarraie and Wright (Reference Ghazal, Al-Samarraie and Wright2020) identified the main factors influencing students’ knowledge in online collaborative environments: interaction and participation, task, student variables, and support. Paulsen and McCormick (Reference Paulsen and McCormick2020) investigated the link between online learning and student engagement in higher education, claiming that student engagement can be crucial for the learning process and improve learning outcomes. Similarly, Muzammil, Sutawijaya and Harsasi (Reference Muzammil, Sutawijaya and Harsasi2020) analyzed student satisfaction and engagement in online learning, revealing that interaction among students, between students and teacher, and between students and content can all have a positive effect on student engagement, which in turn improves student satisfaction.

Since telecollaborative studies are based on interactions between learners from different backgrounds, it is very common that they investigate the intercultural component, usually based on Byram’s (Reference Byram1997) model for understanding the knowledge, attitudes, and skills required for ICC. He proposes two sets of skills: (a) interpreting and relating, and (b) discovery and interaction. The first set of skills refers to the ability to identify the fundamental values and viewpoints; the second set, which is the specific focus of our study, concerns the abilities to obtain new information about the target culture and communicate successfully with members of that culture under the constraints of real-time interaction. In order to explore this component of Byram’s model of ICC, we traced the type of questions the participants posed, emotive words, expressions of alignment, wishes and desire, and audio-visual resources.

Such interactional skills have interested telecollaboration researchers. Lenkaitis, Calo and Escobar (Reference Lenkaitis, Calo and Escobar2019), for instance, investigated students from a Mexican and a US university and how their intercultural competence was affected by a five-week telecollaborative exchange. This study demonstrated the value of integrating telecollaboration into L2 learning and teaching, as it gave learners an opportunity to explore the intersection of language and culture. In another study, Balaman and Doehler (Reference Balaman and Doehler2021) examined an L2 adult speaker over the course of four years and showed that learners adjusted their grammar for interaction while adapting to new situations, languages, or media. However, research in secondary school settings, the focus of our study, is less prolific.

In 2013, Ware analyzed the interactions of 102 adolescents in Spain and the US in a classroom-based, international online exchange focusing on the skills of discovery and interaction within a model of ICC. The findings show that the participants displayed a range of interactional features that have been previously documented as interculturally strategic in similar educational contexts. The following year, Ware and Kessler (Reference Ware and Kessler2016) used a case study design to analyze the patterns of interaction emerging in the literacy practices of adolescents as well as the pedagogical issues that arose when introducing telecollaboration into the L2 learning environment. The participants were 38 students and two teachers from Spain and the US. Learners exchanged text-based messages, hyperlinks, and embedded videos through private blogs. The researchers found that adolescents posed more information-seeking questions than interpretation questions, and that the more successful groups used a higher number of markers of openness. This strategy helped them build personal relationships and provided greater depth to the responses.

Despite these studies, however, the bulk of existing research on telecollaboration still concerns, primarily, higher education institutions. This is why the present study addresses the insufficient research of strategies evidencing interactional skills in secondary school telecollaboration settings. Moreover, studies have mostly focused on student and teacher satisfaction, task design, negotiation of meaning, and challenges and factors for successful ICC. As a novelty, we address the exploration of variation in strategies depending on the interlocutor.

Our research questions are:

-

1. What interactional strategies do secondary school learners of English as a foreign language use during intercultural telecollaborative interactions?

-

2. Does the frequency of use of different interactional strategies depend on the interlocutor?

-

3. If so, what factors influence strategy choice in relation to the interlocutor?

3. Design and methodology

3.1 Context and participants

In the present paper, we use a case study exploratory approach (Ware & Kessler, Reference Ware and Kessler2016) and analyze the EFL interactions between secondary school students in Spain and Bulgaria during two videoconferencing intercultural projects. Three schools participated: a Bulgarian school, a Spanish public school, and a Spanish private language school. A total of 28 students from the three schools, aged between 10 and 15 years old, participated.

Since all the participants were under the age of 18, their parents signed a consent form allowing their children to participate in the videoconferencing intercultural exchange and for the sessions to be video-recorded (see Supplementary Material A).

Data were collected from all telecollaborative interactions between the 10 Bulgarian students and their 18 partners in the two Spanish schools – 12 in the Spanish public school and six in the Spanish private language school (Section 3.3) – who volunteered for the research. For the present article, three Bulgarian students, Daniel, Maria Jana, and Tania, have been selected out of the group as case study participants in order to provide in-depth analyses as well as representative illustrations of the strategies under investigation (Section 3.2).

3.2 Selection of case study participants

To select three case study participants from our focus classroom in Bulgaria, first a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) method was applied to ensure that they were representative of the whole group of volunteers (Supplementary Material B). After counting the relative frequencies of use of each interactional strategy per participant (Supplementary Material C, D, and E), the HCA (using “pvclust” package) revealed three statistically significant clusters, each representing a group of students who used the interactional strategies with similar frequency. We therefore chose one student from each cluster based on two additional criteria: they had participated in both projects, and had the highest total time of telecollaborative communication in their respective cluster. This greatest time of participation offered the potential for more variety and occurrences of strategies within the data, increasing the representativity of the findings. Thus Daniel, Maria Jana, and Tania were identified as the case study participants for this paper.

3.3 The telecollaborative projects and data collection procedures

All participants were involved in one-to-one dyadic telecollaborative sessions using Zoom software as an extracurricular activity embedded in two pedagogical projects. Sessions lasted approximately half an hour each. Each project included five sessions in which, previously, students discussed topics selected from a list of possible familiar or curriculum-related subjects that pre-project questionnaires and interviews had revealed as interesting and appealing to participants. To motivate and stimulate participants, the teachers selected five final discussion topics from this list (Supplementary Material F and G). Before and after each project, students answered questionnaires and participated in semi-structured individual interviews (Supplementary Material H to K). These two instruments helped us gather basic information on students’ interests and hobbies, expectations regarding the project, attitudes towards the target culture, as well as learners’ experiences during the session, technology effectiveness, session objectives, and suggestions for potential improvements.

The first project lasted for five weeks. During sessions, one researcher was present in the Spanish school room in order to make observations and take field notes, monitor the activity, and provide technical support if necessary. Before every session, the EFL teacher provided participants with task sheets with sample content questions related to the discussion topic and which students could use to facilitate their conversation. This sheet had been devised by the teacher at the participating Spanish school who wanted to provide additional support and make sure that the experience was comfortable and enjoyable for the learners. The teacher at the Bulgarian school, however, decided not to do so. Each teacher provided his/her own students with instructions as to how to accomplish the telecollaborative task.

The second project also lasted for five weeks, and learners from the Bulgarian school who participated in the first project were paired in one-to-one dyads for the second project with students from the Spanish private language school. Students also met once a week for half-hour videoconferencing sessions, and the procedures for choosing topics were the same as in the first project.

All project sessions were recorded via Zoom, which yielded the main dataset of 19 hours of recording from all 28 participants. The audio-visual data was complemented with field notes taken by one of the researchers during in-class observation of students’ behaviors before, during, and after the sessions. Field notes were taken as unobtrusively as possible, and after-session logs were created. These notes were used to track the researchers’ perspective on students’ interactional strategies as well as to clarify ambiguities in the recordings where necessary. The researcher and the class teachers agreed to minimize the impact of their presence in the room as much as possible and just provided technological support if needed.

In sum, the data analyzed came from video recordings of project sessions, classroom fieldnotes, pre- and post-project questionnaires, and pre- and post-project interviews.

3.4 Data analysis

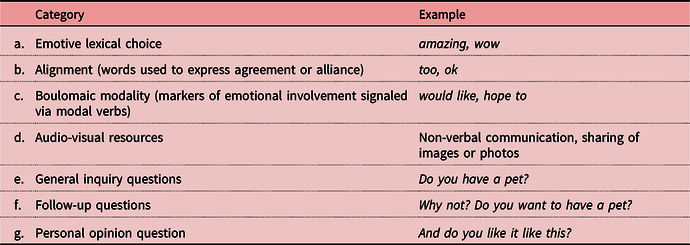

After transcription, we coded the telecollaborative exchanges for strategy use. To categorize the interactional strategies used by the participants, we applied analytical categories from previous studies in secondary school contexts (Ware, Reference Ware2013; Ware & Kessler, Reference Ware and Kessler2016) (Section 2). To assign codes to the video recordings, we used MAXQDA data analysis software, which allowed us to transcribe, mark, codify, and quantify segments of the file. MAXQDA also helped us compare documents, visualize connections in the data and, importantly, incorporate quantification. Drawing on grounded theory (Hadley, Reference Hadley2017), we reread the transcripts iteratively and refined categories until saturation, finishing with seven categories of strategy shown in Table 1. The two researchers recursively replicated the coding and discussed it until agreement was reached. Finally, we counted the frequency of strategy use by participants. Our quantitative analysis was thus based on the comparison of participants’ frequencies of strategy use (Table 2).

Table 1. Categories with examples

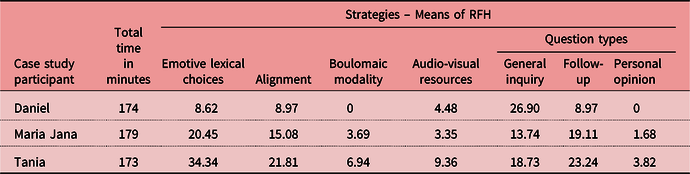

Table 2. Relative frequency per hour (RFH) means of the case study participants’ use of the strategies

The qualitative dimension consisted of content analysis of the video-recorded data, questionnaire, and interview answers as a “systematic, replicable technique for compressing many words of text into fewer content categories based on explicit rules of coding” (Stemler Reference Stemler2001: 1). The qualitative analysis provided explanations for differences in interactional behavior. New categories and subcategories started to emerge when coding, and the final list is as follows:

4. Results

Overall, the most frequently used interactional strategy was general inquiry questions about personal background, followed by emotionally tagged lexical choices, follow-up questions, and alignment. The least frequently used strategies were audio-visual resources, boulomaic modality, and personal opinion questions (see Supplementary Material C, D, and E where we present a numerical overview of how frequently each participant used each strategy).

As explained in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, Daniel, Maria Jana, and Tania from the Bulgarian school were selected as case study participants for the present study in order to provide representative illustrations of strategy use that could be linked to interactional success. For an initial overall grasp of how differently each participant made use of strategies, in Table 2 we present the relative frequency per hour (RFH) of use for each codified strategy.

As Table 2 shows, similar general patterns of strategy use emerged. Daniel used general inquiry questions most often but neither personal opinion questions nor boulomaic modality. Interestingly, Maria Jana and Tania followed similar patterns, often utilizing emotive lexical choices, follow-up questions, and alignment, but rarely personal opinion questions. Despite these overall similarities, the numerical data on their use of interactional strategies revealed differences related to interlocutor, which merit further investigation. In the following, we focus on each of the three students in turn to explore the strategies predominantly used with each interlocutor and some of the factors that appear to influence those choices.

4.1 Daniel, or the use of interactional strategies to fulfill one’s own intercultural learning agenda

During the first project, Daniel, 11 years old, B1/B2 English level, attended the Bulgarian language school twice a week. In this project, Daniel interacted with Noah, Hana, and Eric from the Spanish public school for a total time of 108 minutes. In the second project, his partner was Pablo, from the Spanish private language school, with whom he collaborated for 66 minutes. In the interview, Daniel said he was very interested in speaking in English with children from a different culture and took the telecollaborative exchanges seriously: “I prepared the topic we would discuss, words I might need. I even practiced with my mom.” This comment suggests Daniel’s awareness of the importance of his language skills, and perhaps consideration for his partner.

As may be seen in Table 3, Daniel’s frequency of use of some strategies changed from one interlocutor to another (see his use of emotive lexical choices or follow-up questions), although his use of other strategies remained stable throughout the two projects: he used neither boulomaic modality nor personal opinion questions while making extensive use of general inquiry questions.

Table 3. Relative frequency per hour (RFH) means of Daniel’s use of the strategies with each partner

In Daniel’s partnership with Hana, we noticed that communication was probably hindered by her apparent low English proficiency level, as she seemed not to comprehend Daniel’s basic questions. Actually, we cannot be sure whether she did not understand the questions or lacked sufficient vocabulary to provide a response. Whenever she did provide an answer, it was brief and without any details. Daniel appeared to be somewhat confused by her replies as he himself explained when, on one occasion, he turned to the boy sitting next to him and commented in Bulgarian, “I ask her what’s her favorite food and she says she doesn’t know … she says I don’t know to everything.” Despite his puzzlement, he turned out to be very persistent in this telecollaboration and carried on asking general inquiry questions, repeating the question or paraphrasing it to make it easier for Hana to understand.

Such active engagement was missing in his interactions with Pablo, a student with a higher command of English, whose detailed descriptions were often not followed up by Daniel. In one such instance, Pablo’s wish to provide in-depth information about the typical drinks of his country leads him to describe, first, what “sangria” is: a refreshing drink made of red wine with pieces of cut fruit. Then, he goes on to explain “vermut,” a typical Spanish aperitif. Daniel’s response was just a brief “Ohhh … ok,” which seemed to leave Pablo perplexed.

Extract 1.

Pablo: If I could change something in the educational system, it will be that don’t do exams. Do a lot of work but don’t do exams because if you are a very good student but you get nervous at an exam and you fail the exam ….

Daniel: Aaaa. … Do you watch news on the TV?

Pablo: Sometimes.

Daniel: Does your TV have something news for Bulgaria sometimes?

Pablo: Ahhhh no! I’ve never seen the news of Bulgaria.

Extract 1 displays Daniel’s lack of alignment after Pablo’s exposition of his idea of a better educational system when asking an unrelated question, “Do you watch news on the TV?” This behavior, however, was coherent with what we found in his interactions with Hana: Daniel very frequently expressed his curiosity about the knowledge his partners had regarding his country, which led him to often ask general inquiry questions. With such questions, he managed not only to make up for Hana’s low command of English but also, as with Pablo, to lead the conversation to areas of his own interest. Thus, Daniel’s questions in Extract 1 were followed by others on what the capital of Bulgaria is, how many people live in Bulgaria, or if the partner had tried Bulgarian yogurt.

In general, then, Daniel posed many general inquiry and much less follow-up and personal opinion questions. Nonetheless, he voiced his motivation and eagerness to request additional information, often revealing curiosity towards the Spanish culture and habits, through questions such as, “Do you like bullfight?”, “How long is one lesson?”, and “What is typical Spanish food?”

Extract 2.

Daniel: Do you play football?

Eric: Yes … and I play hockey and play the piano.

Daniel: Ohhh … hockey is very strange for Bulgaria. We don’t have hockey team.

In Extract 2, the statement that caught Daniel’s attention is the one related to hockey, as he is genuinely surprised and reveals his astonishment right away. In his questionnaire, Daniel mentioned that he was surprised to discover that “Spanish children play hockey,” since both partners Eric and Hana practiced that sport. Another participant from his class mentioned that Daniel “was very surprised that Spanish children play hockey. He told us after the session, in class and we were also surprised. Hockey! Football yes, but hockey!”

Overall, Daniel seemed to be committed to interactions that would allow him to learn about the other culture. To do so, he strove to maintain the conversation, even when interacting with Hana and Eric with low language proficiency. However, this clear goal also made him align less and show far less emotion with Pablo, who was able to elaborate on topics that had not been chosen by or were of no interest to Daniel. We could, therefore, argue that Daniel had interactional goals concerning who selects and maintains the topics, and that, ultimately, he wanted to be in charge of the communication.

4.2 Maria Jana, or the making of intercultural personal connections and the co-construction of meaning

Thirteen-year-old Maria Jana, B2/C1 English level, just like Daniel, attended the Bulgarian language school twice a week. In her first project with participants from the Spanish public school, Maria Jana communicated with three students – Manuel, Carla, and Malek – for a total of 64 minutes. In the second project, her partner was Patricia from the Spanish private language school with whom she collaborated for a total of 115 minutes and formed a strong bond. As Maria Jana stated, “I learned a lot from the project” and “it was a very pleasant experience.” Actually, she proved to be very motivated and interested in the telecollaboration and, despite her personal claim of her being quite shy and nervous, she showed a high level of self-confidence during the sessions.

As may be seen in Table 4, Maria Jana’s frequency of use of strategies also changed from one interlocutor to another. Interestingly, she used most of the strategies more often with her partner in the second project, Patricia, and used general inquiry and follow-up questions a lot less frequently than with the other participants.

Table 4. Relative frequency per hour (RFH) of Maria Jana’s use of strategies with each partner

Extract 3 is an illustrative example of the alignment moves that she used in her interactions with Patricia: Maria Jana did not simply express her feelings or opinions but used longer and evaluative comments, adding details or reasons to justify her views.

Extract 3.

Patricia: I used to do some sport but I didn’t lose any weight so then they recommended me to increase the level of sport and now the effect is very visible.

Maria Jana: Yes, I agree with you. The sport is more important, not diets. Actually, I also started doing more sport by myself and I notice it too.

As noted, the use of boulomaic modality is a marker of emotional involvement or rapport through which the speaker tends to make personal connections with partners. In her first project, Maria Jana did not use any boulomaic modality (Table 4), whereas in her interaction with Patricia in the second project, she utilized it often. In Extract 4, she does it for different purposes: to reveal her hopes and desires, to align with her partner’s interests, and to indicate similarity of opinions.

Extract 4.

Maria Jana: My parents haven’t traveled a lot, I would like to travel more than them.

Patricia: Yes, I love traveling a lot.

Maria Jana: I would love to go to Finland.

Patricia: I want to go too. (She explains that she wants to become a teacher and Finland is known to have the best educational system.)

Maria Jana: Yeeees, that would be good. I have always envied their system.

Extract 5 illustrates Maria Jana’s desire to broaden the conversation, persistence in gathering more information about her partner Manuel from the Spanish public school, and demonstrate attentiveness and interest to him. Despite his one-word answers, we notice that she maintains her intention to carry on with the interaction by posing follow-up questions in subsequent turns.

Extract 5.

Maria Jana: Do you like your school?

Manuel: Mmm … no!

Maria Jana: Why? You don’t like studying?

Manuel: Yes.

Maria Jana: Is there something you want to change in your school?

Manuel: Yes. … What’s your favorite subject?

Maria Jana: I like P.E. and drawing classes. Do you like Maths?

Manuel: Nooo.

Maria Jana: Is it difficult?

Manuel: Yes.

The quantitative results show that Maria Jana used more general inquiry and follow-up questions with the participants in the first project compared to those she used with her partner in the second project. Even so, despite this persistence, she was not able to trigger the same reaction from her partners in the first project. A likely explanation could be found in their lower English proficiency. On the contrary, in the second project, although Maria Jana posed fewer such questions, the interaction with Patricia was much more collaborative and prolific. They aimed at partnership and co-construction of meaning, which deepened the relationship between them. Also, Maria Jana asked more opinion questions of Patricia than of participants from the Spanish public school.

This, once again, as Extract 6 shows, demonstrates her attention to Patricia and her desire to build a personal relationship through engaging in more profound and thought-provoking conversations.

Extract 6.

(Patricia explains that there are different regions in Spain, that she lives in Catalonia, and that some people think that Catalonia needs to be independent.)

Maria Jana: And do you want it to be independent country?

Patricia: I don’t mind. I know that there are some points that I am in favor but there are some points that I am against ….

As Maria Jana explained in her interview, “this project helped me a lot to improve my self-esteem. I like very much to learn about other cultures and countries. And not to forget, I met one incredible girl.” On the contrary, during the first project, Maria Jana did not establish a close connection with any of the participants from the Spanish public school, most likely because of the limited time of interaction and the fact that she had to communicate with a different person in each session. This probably led to the very low use of emotionally tagged words, boulomaic modality, audio-visual resources, and personal opinion questions.

4.3 Tania, or how more stable relationships trigger more strategies and more successful interactions

Twelve-year-old Tania had a B2/C1 English level. In the first project, she communicated with Malek, Hugo, and Berta for a total of 75 minutes; in the second project, she had a stable partner, Matias, with whom she collaborated for 98 minutes. Tania was always diligently prepared for the topics to be discussed and frequently brought examples of typical foods or objects, such as a typical Bulgarian salad that she had especially prepared for the meeting. She seemed dedicated and inquisitive and was very eager to learn about the Spanish culture and traditions, frequently requesting details and clarifications: “I would like to discuss more profound topics and learn more about the people and what they do … and culture of course, this is clear. … You are always curious to know and you ask them about their culture and food.”

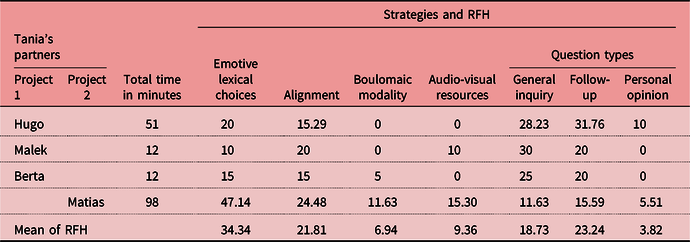

As may be seen in Table 5, Tania preferred the use of questions of different kinds during the first project, whereas she used other interactional features more frequently with Matias, her partner in the second project.

Table 5. Relative frequency per hour (RFH) of Tania’s use of strategies with each partner

Extract 7, in which Tania and Matias discuss preferences of music, is representative of Tania’s use of emotionally tagged words and expressions throughout her sessions with Matias. She expresses not only alignment with him but also interest. After Matias’s interpretation of the “Despacito” lyrics, her response “Oh, wow! How interesting!” demonstrates her receptiveness towards objects or events that are different from her own culture (Byram, Reference Byram1997). Tania was also ready to reveal her emotions, confessing that she cries whenever she hears this song. Sharing her feelings with her partner is a possible sign of her wish to establish a close personal bond with him.

Extract 7.

Matias: I hate this song.

Tania: Ohhh gooood! I don’t like it, too. … I love Shawn Mendes. (Matias plays a song by Shawn Mendes on his phone.)

Tania: This song is so emotional that I cry every time I hear it.

Matias: I like this song.

Tania: Ohh, you love it? How cool!

……

Tania: Because you are Spanish I wanted to ask you something. Can you explain the meaning of “Despacito” song to me? (Matias provides his interpretation.)

Tania: Oh wow! How interesting! …

Tania’s alignment moves show that she used these interactional devices to express her understanding of Matias’s previous turns. Nonetheless, her most frequently used expressions of acknowledgement found in data from the first project were tagged as a low degree of alignment (Extract 8).

Extract 8.

Berta: My favorite food is pizza.

Tania: I like pizza, too.

Berta: I play gymnastic.

Tania: I go to gymnastics, too.

With Matias from the second project, she indicated a much greater level of involvement in comparison to that with learners from the Spanish public school, who had a lower language level than hers. As an example, see her reply to Matias saying that he wanted to work as a reporter – “Yeah, I know. Last time you told me and if you want some advice I can ask my sister to give you.” – or her prompting for more elaboration – “Do you like it? I am going there soon with my family so can you give me some advice on what to do there?” – when Matias said that he had been to Italy.

In her interview after the first project, Tania stated that she was passionate about exploring different cultures and traditions and that in the second project she “would like to discuss more profound topics and learn more about the people and what they do.” However, we need to consider that the first project turned out to be less strictly organized and, as a result, Tania communicated with three partners, whereas in the second project she had one stable partner for the four sessions. In sum, Tania used more interactional strategies in this more stable partnership and displayed the skills of information discovery and interaction more successfully when collaborating with Matias with whom she was able to establish a longer and, thus, more stable relationship.

5. Discussion

As noted in Section 2, the skills of information discovery and interaction (Byram’s, Reference Byram1997, ICC model) form a component of the larger ICC construct, and, by focusing on them, we can understand how EFL learners may or may not build successful intercultural relationships with telecollaborative partners.

By analyzing our participants’ interactional strategies, we found that, in general, they tended to use emotive words and phrases and very often displayed alignment with partners. Besides, the study has shown that participants posed a large number of general inquiry questions rather than follow-up and personal opinion questions, results that are coherent with those of Ware and Kessler (Reference Ware and Kessler2016). Also, in both Ware and Kessler’s and our study, the more successful dyads – which were also the most stable ones – tended to signal their engagement with partners through the tools of modality, lexical choices, and alignment markers.

It has been demonstrated that the use of such strategies is linked to interactional success (Balaman, Reference Balaman2021; Dooly, Reference Dooly, Masats and Nussbaum2021; Ware, Reference Ware2013; Ware & Kessler, Reference Ware and Kessler2016). What we found was that learners chose and utilized the interactional strategies with varying frequency depending on who their interlocutor was, which, in turn, was also related to the specific classroom or school context the students belonged to. Daniel used more interactional strategies with his three partners in the first project than with his partner in the second one, regardless of their command of the English language. Maria Jana and Tania, on the contrary, used the strategies more frequently with their partners in the second project, who had a better command of the language than their partners in the first one. Paulsen and McCormick (Reference Paulsen and McCormick2020) demonstrated that there is a link between online learning and student engagement, stating that student engagement can be vital for the learning process and successful outcome of the collaboration. In general, as Ware (Reference Ware2013) documents, students tend to signal their engagement with certain partners through the tools of lexical choices, alignment markers, and modality. However, in our study, we found that participants would employ fewer such markers of openness with some of their interlocutors. In fact, participants’ behavior seemed to be affected by numerous, complex factors; we discuss some crucial ones that we uncovered in our data as follows.

A first factor would be the stability of project partners. Here, in the first telecollaborative project, participants communicated with several partners, whereas in the second project they had one single stable partner. The interactions within these stable dyads proved to be more collaborative and prolific, as we saw in Maria Jana and Tania’s collaborations. Stable participants tended to use more follow-up and personal opinion questions compared to less stable dyads. We interpret the use of such questions as signaling the desire to widen the conversation, gather more information, and demonstrate interest. In their study, Ghazal et al. (Reference Ghazal, Al-Samarraie and Wright2020) claim that some key factors influencing students’ knowledge building in an online collaborative environment are related to interaction and participation, task, student, and support, specifying that the continuity of the contribution received from individual students is one such crucial factor.

A second factor that seemed to lead to more successful telecollaborative interactions was the similarity of linguistic skills between partners. Overall, if the dyad had similar English proficiency, participants like Maria Jana and Tania utilized the interactional strategies more frequently, which resulted in more in-depth conversations. In contrast, if there was a considerable gap between their language skills, learners faced understanding problems and struggled to find topics to discuss, which led to frustration and a decrease in motivation to maintain the conversation, as we observed in Daniel’s interaction with Pablo. These findings are in line with O’Dowd and Ritter’s (Reference O’Dowd and Ritter2006) and Hauck’s (Reference Hauck2007), who have identified language proficiency level as one of the crucial factors for the successful outcome of telecollaboration. Muzammil et al. (Reference Muzammil, Sutawijaya and Harsasi2020) also demonstrated that interaction among students, between students and teacher, and between students and content have a positive effect on student engagement, and then on student satisfaction. The results derived from our recordings were confirmed by participants’ viewpoints expressed in the questionnaires, as they also considered the difference in linguistic proficiency as the major drawback in the sessions.

A third crucial factor is the student’s personality and learning style since, as we have seen here, some learners may mark their speech with expressiveness or feelings and others may scarcely do so. Despite the fact that the study did not specifically investigate these factors, we saw clearly that certain participants were more nervous than others, which affected communication. Daniel, for instance, demonstrated interest, although he focused on a kind of intercultural learning agenda of his own. Likewise, Tania and Maria Jana demonstrated willingness to interact, which led to a successful telecollaborative partnership. According to Dewaele (Reference Dewaele, Loewen and Sato2017), such individual differences also influence interaction. In line with his claims, the results of our study showed how differently participants in the intercultural tellecollaborative projects may express motivation and interest in the interactions. In their recent study, Nishio and Nakatsugawa (Reference Nishio and Nakatsugawa2020) suggested that the concept of successful collaboration is context dependent, and participants may have different definitions and understandings of successful participation, which could cause tension with respect to participation patterns and affect other aspects of the interaction.

6. Conclusions

Our study revealed that the participants in the telecollaborative educational projects demonstrate differences in interactional behavior and utilize interactional strategies with varying frequency depending on their interlocutor. The results also pinpoint some crucial factors in the design of such projects if learners are to implement skills of discovery and interaction successfully in real time.

Although these factors should certainly be taken into account when organizing a telecollaborative project, we believe that we cannot predict all potential hindrances that might appear during intercultural interactions. It is unrealistic to expect that intercultural partners always have similar motivation, linguistic skills, interests, or personalities, an issue that learners will one day have to face in real life and should be prepared to cope with. As Belz (Reference Belz2004) claims, “these contextually-shaped tensions are not to be viewed as problems that need to be eradicated in order to facilitate smoothly functioning partnerships […]. Structural differences frequently constitute precisely these cultural rich points that we want our students to explore” (p. 48–86 ). We believe that telecollaborative projects like the ones investigated here could prepare learners to deal with the nervousness that may arise when communicating interculturally in a foreign language. Such projects may function as opportunities to practice, helping learners to identify cultural differences and be aware of their own cultural specificities, as in the present study.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344023000228

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participating schools, teachers, and students for their collaboration and the funding received by one author during the final stages of this research (AEI/FEDER, UE-PGC2018-098815-B-I00 and PID2022-141945NB-I00).

Ethical statement and competing interests

Ethical procedures followed those of the Translinguam research project (FFI2014-52663-P), approved of and funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitivity. All participants were volunteers and since they were under the age of 18, we received written consent from their parent(s). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

About the authors

Yordanka Chimeva is working in the field of telecollaboration, ICT in foreign language acquisition, and intercultural communicative competence. She specializes in the use of synchronous internet videoconferencing to enhance interaction and intercultural competence in foreign language education.

Mireia Trenchs-Parera is a professor of applied linguistics and multilingualism. Her interests include the investigation of plurilingualism, transcultural competence, and language policies in higher education (the Translinguam-Uni Project), language attitudes, ideologies and practices in Catalonia, and foreign language education in multilingual and study abroad contexts.

Author ORCIDs

Yordanka Chimeva, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3461-4735

Mireia Trenchs-Parera, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1646-550X