Book contents

- Author and Audience in Vitruvius’ De architectura

- Greek Culture in the Roman World

- Frontispiece

- Author and Audience in Vitruvius’ De architectura

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Plates

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Greek Knowledge and the Roman World

- 2 The Self-Fashioning of Scribes

- 3 House and Man

- 4 Art Display and Strategies of Persuasion

- 5 The Vermilion Walls of Faberius Scriba

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index Locorum

- General Index

- References

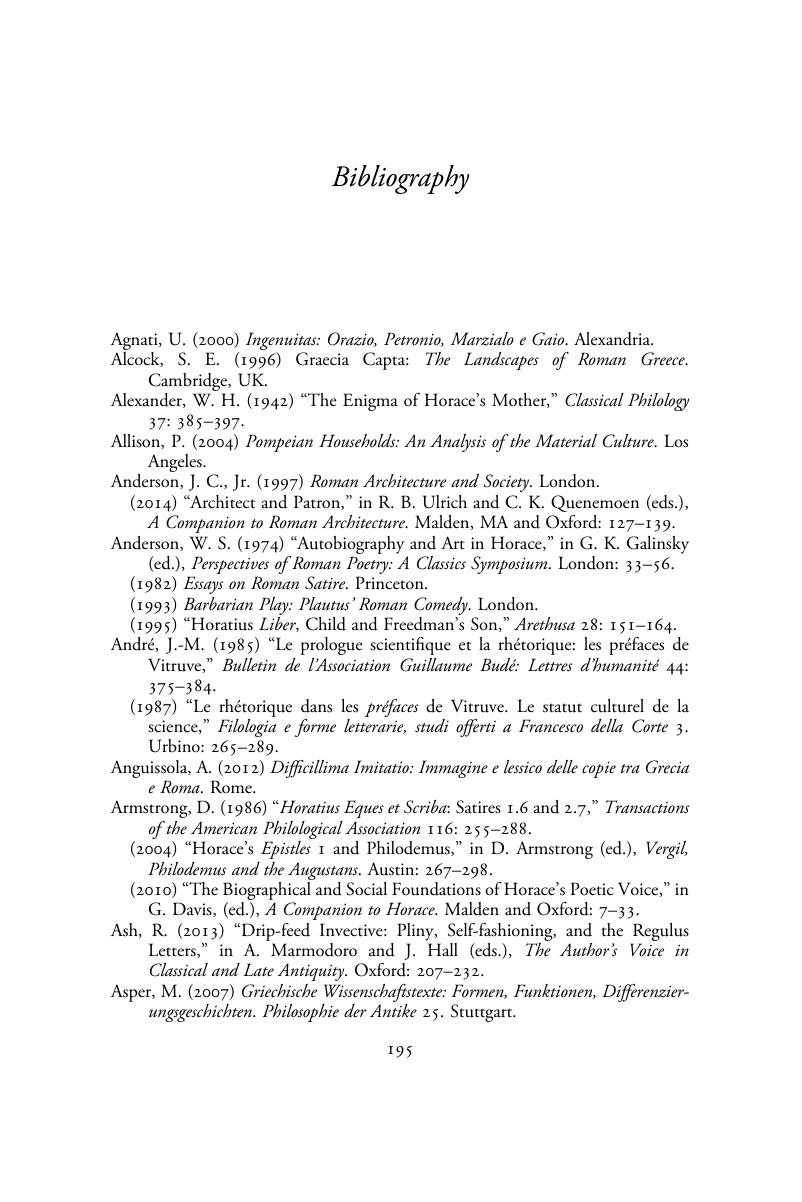

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 November 2017

- Author and Audience in Vitruvius’ De architectura

- Greek Culture in the Roman World

- Frontispiece

- Author and Audience in Vitruvius’ De architectura

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Plates

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Greek Knowledge and the Roman World

- 2 The Self-Fashioning of Scribes

- 3 House and Man

- 4 Art Display and Strategies of Persuasion

- 5 The Vermilion Walls of Faberius Scriba

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index Locorum

- General Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Author and Audience in Vitruvius' De architectura , pp. 195 - 223Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017