With the defeat of the Shang, the Zhou royal house positioned itself at the ideological center of a network held together by personal relationships with the early kings. To maintain this central position in the new post-Shang hierarchy, and to pursue their project of state-building through delegation of authority, the Zhou kings drew on one of their primary cultural advantages: their familiarity with Shang-style ancestral ritual. In doing so, the royal family faced the challenge of retooling the well-established Shang ritual system, centered on a supreme lineage tracing its ancestry back more than twenty generations, to meet the needs of a recently forged coalition of elite populations.

The following analysis explores the political details of this Western Zhou adaptation of Shang ancestral ritual. Through a close look at the records of individual ritual techniques, it shows that royal ancestral ceremonies reinforced the king’s role as arbiter of prestige in Zhou elite society and inculcated principles of Zhou social organization. High-ranking elites attended these ceremonies, took part in them, and duplicated them within their own domains, in some cases at the king’s express recommendation. They cast inscribed bronzes commemorating their attendance and used them in their own ancestral cults and burial practices, appropriating the memories of these ceremonies as tools for building personal and lineage identities. The Zhou take on Shang ancestral ritual thus made its way across, and indeed helped form, the Zhou cultural sphere. Over time, however, some ancestral-ritual techniques that offered substantial benefit to practitioners of varied status continued, while others, the lion’s share, faded from the inscriptional record. This process culminated in a break between the ritual practices of the royal house and those of nonroyal Zhou elites as portrayed in bronze inscriptions. Terms that came into vogue after this break would heavily influence later characterizations of Western Zhou ritual.

Since its goal is to understand how different Western Zhou elites used rites to mediate controversies over group formation, identity, and membership, this analysis focuses whenever possible on the people involved in rites and their relationships to each other both during and outside the context of the rite.Footnote 1 It distinguishes between ritual techniques that appear in inscriptions as having been performed by both kings and nonroyal elites; those for which only royal performances are recorded; and those that, in the inscriptions, show no connection to the royal house.

Shared Ritual Techniques

Most ancestral-ritual techniques in Western Zhou bronze inscriptions are attributed at some point to both kings and lesser aristocrats. Certain techniques became quite widespread, making up a basic rubric of Zhou ancestral ritual that endured throughout most of the period. The following discussion explores how three such techniques – hui-entreaty, zheng-offering, and zhu-invocation – operated as foci of Western Zhou politics and identity.

Hui  (Entreaty)

(Entreaty)

The activity known as hui ![]() , “entreaty,” was one of the most ubiquitous devotional practices of the Western Zhou.Footnote 2 Several inscriptions declare hui-entreaty as an intended purpose of the vessels that bear them. Like the corresponding Shang technique, the Western Zhou practice of hui entailed requesting favors of supernatural forces.Footnote 3 Parallel use of similar verbs in a number of inscriptions confirms this; for example, in that of the Bo Hu gui 伯椃簋 (4073) (an early-middle Western Zhou vessel), hui acts as a compound verb with qi 祈, “to pray for,” in a request for longevity.Footnote 4 Uses of hui in this manner are well distributed chronologically across the corpus of Western Zhou inscriptions (

in the Appendix). Most such bronzes with established provenance stem from the Zhou heartland in Shaanxi.Footnote 5

, “entreaty,” was one of the most ubiquitous devotional practices of the Western Zhou.Footnote 2 Several inscriptions declare hui-entreaty as an intended purpose of the vessels that bear them. Like the corresponding Shang technique, the Western Zhou practice of hui entailed requesting favors of supernatural forces.Footnote 3 Parallel use of similar verbs in a number of inscriptions confirms this; for example, in that of the Bo Hu gui 伯椃簋 (4073) (an early-middle Western Zhou vessel), hui acts as a compound verb with qi 祈, “to pray for,” in a request for longevity.Footnote 4 Uses of hui in this manner are well distributed chronologically across the corpus of Western Zhou inscriptions (

in the Appendix). Most such bronzes with established provenance stem from the Zhou heartland in Shaanxi.Footnote 5

Commissioners of vessels for hui occupied a variety of state and lineage positions. Several bore the epithet bo, “Elder,” suggesting that they were first sons or lineage heads; the name of the commissioner of the Ji Xin zun 季![]() 尊 (05940), however, suggests that he ranked low in the sequence of his siblings.Footnote 6 The preeminent commissioner of such a bronze was King Li, normally identified as commissioning the Hu gui.Footnote 7 Xing, of the Xing zhong 𤼈鐘 (246), seems also to have been of high status, given that several of his ancestors, including his father, carried the title gong 公.Footnote 8 Determining the political status of the remaining commissioners is difficult, but Shi Chen 事晨, for example, seems based on his title to have been someone’s subordinate; that the Shi Chen ding 事晨鼎 (2575) inscription uses the actions of a lineage head, “Elder Father Yin” (Bo Yinfu 伯殷父), as a dating reference suggests that Shi Chen occupied a subordinate position within his line. By the late Western Zhou and the Spring and Autumn period, gender entered the picture as well. The X Chefu gui 車父簋 (3881–3886), the Bo Shi Si Shi ding 伯氏姒氏鼎 (2643), and the Qi Bo Mei Wang pan 杞伯每亡盆 (10334) were all commissioned by their namesakes on behalf of figures whose names suggest that they were female; all also declare hui-entreaty as a purpose.Footnote 9

尊 (05940), however, suggests that he ranked low in the sequence of his siblings.Footnote 6 The preeminent commissioner of such a bronze was King Li, normally identified as commissioning the Hu gui.Footnote 7 Xing, of the Xing zhong 𤼈鐘 (246), seems also to have been of high status, given that several of his ancestors, including his father, carried the title gong 公.Footnote 8 Determining the political status of the remaining commissioners is difficult, but Shi Chen 事晨, for example, seems based on his title to have been someone’s subordinate; that the Shi Chen ding 事晨鼎 (2575) inscription uses the actions of a lineage head, “Elder Father Yin” (Bo Yinfu 伯殷父), as a dating reference suggests that Shi Chen occupied a subordinate position within his line. By the late Western Zhou and the Spring and Autumn period, gender entered the picture as well. The X Chefu gui 車父簋 (3881–3886), the Bo Shi Si Shi ding 伯氏姒氏鼎 (2643), and the Qi Bo Mei Wang pan 杞伯每亡盆 (10334) were all commissioned by their namesakes on behalf of figures whose names suggest that they were female; all also declare hui-entreaty as a purpose.Footnote 9

The concept of hui-entreaty was thus widespread among Western Zhou elites who could possess inscribed bronzes. Vessels that declare hui as a purpose rarely specify the entreaty’s intended target directly.Footnote 10 When targets are obliquely specified, they are patrilineal ancestors of the vessel commissioners rather than living figures or other supernatural entities.Footnote 11 Overall, the inscriptions portray hui-entreaty as a standard ancestral-ritual technique, solidly entrenched within Zhou society and closely tied to the production of bronzes, which endured throughout the period.

Hui as Vehicle of Political Patronage: The Ze Ling Vessels

Hui apparently described one of the primary motivations for creating inscribed bronzes, and as such, most of its appearances in nonroyal inscriptions are formulaic. The inscriptions of the Ze Ling fangzun 夨令方尊 (6016) and Ze Ling fangyi 夨令方彝 (9901), however, furnish more detail about the political context of hui than any other source.Footnote 12

The Ze Ling inscriptions begin with an account of honors granted to the vessel commissioner’s superior –Ming Bao 明保, the Duke of Zhou’s son – at a royal audience.Footnote 13 After receiving a broad-ranging appointment from the king, Ming Bao (also called “Duke Ming” [Minggong 明公] in the inscription) undertook a mission to the eastern capital Chengzhou, where he issued orders to a variety of officials.Footnote 14 Based on the word order, it appears that Ze Ling, the vessel commissioner, was present and was ordered to accompany Ming Bao to Chengzhou to work with the Ministry (qingshiliao) there.Footnote 15 Ming Bao completed his business with a series of sacrificial offerings at important venues in the Chengzhou area: the Jing Temple (Jinggong 京宮);Footnote 16 the Kang Temple (Kanggong 康宮);Footnote 17 and a location called wang, “royal,” likely identifiable with the wangcheng 王城, or “King’s City,” on which much debate about the early structure of Chengzhou/Luoyang centers.Footnote 18 After the third leg of his tour, Duke Ming issued a set of rewards:

明公易(賜)亢師鬯、金、小牛,曰:用![]() 。易(賜)令鬯、金、小牛,曰:用

。易(賜)令鬯、金、小牛,曰:用![]() 。廼令曰:今我唯令女(汝)二人,亢眔夨,奭

。廼令曰:今我唯令女(汝)二人,亢眔夨,奭![]() Footnote 19(左)右于乃寮

Footnote 19(左)右于乃寮![]() (以)乃友事。乍(作)冊令(命)敢揚明公尹氒(厥)

(以)乃友事。乍(作)冊令(命)敢揚明公尹氒(厥)![]() ,用乍(作)父丁寶

,用乍(作)父丁寶![]() 彝,敢追明公賞于父丁,用光父丁。〔

彝,敢追明公賞于父丁,用光父丁。〔![]() 冊〕

冊〕

Duke Ming awarded Kang Shi dark wine, metal, and a young ox, saying, “Use these for hui-entreaty.” [The Duke] awarded Ling dark wine, metal, and a small ox, saying, “Use these for hui-entreaty.” [He] then commanded, “Now I am commanding you two men, Kang and Ze, to fervently assist each other with your Ministry’s and your associates’ business.”Footnote 20 Document Maker Ling dares to extol the beneficence of ChiefFootnote 21 Duke Ming, thereby making a precious offering vessel for Father Ding, daring to carry Duke Ming’s reward on to Father Ding,Footnote 22 thereby to glorify Father Ding.

The dynamic of Duke Ming’s relationship with his various subordinates is of note. Given the scope of his commands from the king, Duke Ming was effectively the royal representative at Chengzhou. He either could not or did not, however, command the personal presence of the full range of elites over whom he had been granted temporary authority. Rather than summoning the officials and regional rulers in question, he is said to have “sent out” (![]() [chu 出]) orders.Footnote 23 In fact, after his commands were finished, Duke Ming paid personal visits to several important local venues, notably including the royal compound, to make offerings. It seems that this sacrificial tour gave Ming Bao the opportunity to shore up local support from both powerful Chengzhou-area lineages and the personnel of the royal holdings there. The eastern capital was still fairly new at this point, and Duke Ming must have needed the support of local elites in order to function well as a royal emissary.Footnote 24

[chu 出]) orders.Footnote 23 In fact, after his commands were finished, Duke Ming paid personal visits to several important local venues, notably including the royal compound, to make offerings. It seems that this sacrificial tour gave Ming Bao the opportunity to shore up local support from both powerful Chengzhou-area lineages and the personnel of the royal holdings there. The eastern capital was still fairly new at this point, and Duke Ming must have needed the support of local elites in order to function well as a royal emissary.Footnote 24

The rewards that Duke Ming issued after the sacrificial tour, and the hui-entreaties they were meant to support, helped channel prestige from the royal house, through the organization of the central government, into the social context of individual lineages. While commanding their help with the Chengzhou branch of the Ministry, Ming Bao rewarded Ze Ling and Kang Shi with the basic resources for an offering event: liquor for drinking, livestock animals for feasting, and metal for producing bronzes. This created a direct relationship between Ze Ling’s and Kang Shi’s service to Duke Ming in his governmental activities and their ability to provide for their lineage cults. Ze Ling then made the provenance of these resources, and hence the details of this relationship, known during his cult activities. The bronze produced thus let Ze Ling maximize the impact of his accomplishments within the social context of his lineage cult by drawing an indirect connection to the Zhou royal house.

Royal Performances of Hui

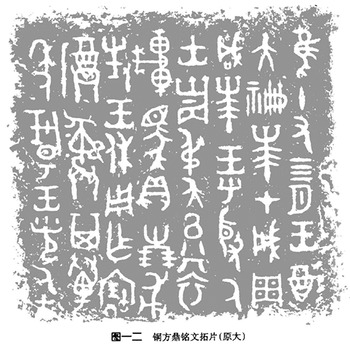

In the early Western Zhou period, royal ritual events that included hui-entreaties provided a context for managing relations with elites of the very highest ranks. A recently excavated bronze, the Shu Ze fangding (NA0915) (Figures 1.1 and 1.2), describes an instance of hui tied to major political events of the early Western Zhou period:

隹 (唯) 十又四月,王 ![]() 大

大![]()

![]() 在成周。咸

在成周。咸![]() ,王乎殷厥士,齊叔夨以

,王乎殷厥士,齊叔夨以![]() 、衣、車、馬、貝卅朋。敢對王休,用乍(作)寶尊彝,其萬年揚王光厥士。Footnote 25

、衣、車、馬、貝卅朋。敢對王休,用乍(作)寶尊彝,其萬年揚王光厥士。Footnote 25

In the fourteenth month, the king performed a ![]() rite and greatly used documents to perform entreaty at Chengzhou. When the entreaty was finished, the king called an audience of his retainers,Footnote 26 [rewarding?] Shu Ze with a skirt, a jacket, a chariot and horses, and thirty strings of cowries.Footnote 27 [Shu Ze] dares to respond to the king’s beneficence, therewith making a precious offering vessel. May [it] praise the king’s honoring of his retainers for ten thousand years.

rite and greatly used documents to perform entreaty at Chengzhou. When the entreaty was finished, the king called an audience of his retainers,Footnote 26 [rewarding?] Shu Ze with a skirt, a jacket, a chariot and horses, and thirty strings of cowries.Footnote 27 [Shu Ze] dares to respond to the king’s beneficence, therewith making a precious offering vessel. May [it] praise the king’s honoring of his retainers for ten thousand years.

The Shu Ze fangding comes from the cemetery of the Jin state rulers, in the Fen River valley of Shanxi.Footnote 28 Li Boqian has plausibly suggested that it dates to the reign of King Cheng, based partly on the Shang-style use of a fourteenth, intercalary month; certainly, the reference to Chengzhou in the inscription means that it postdates the establishment of that polity.Footnote 29 Based on a paleographical analysis of the character ze 夨, Li further suggests that the vessel was probably produced by the figure known in historical records as Tangshu Yu 唐叔虞, the first ruler of the Jin state and younger brother of King Cheng, whom the Bamboo Annals record King Cheng installed during the tenth year of his reign.Footnote 30 Whether or not this was so, the circumstances of the vessel’s discovery virtually require that it belonged to an early member of the Jin ruling line.

Figure 1.1 The Shu Ze fangding.

The case describes a pattern common in the inscriptions: The king conducts a major ritual event involving ancestral offerings; during or after the ceremonies, he then publicly rewards a subordinate, who casts an inscribed bronze to commemorate the event. The Shu Ze fangding inscription records no recounting of merits, assistance with the rite, report of a successful campaign, or other justification for the commissioner’s presence beyond the assumption that he numbered among the “retainers” (shi 士) the king summoned. The vessel commissioner’s status itself was apparently sufficient justification for both his presence at the rite and the reward.

I strongly suspect that Li Boqian is correct in attributing the vessel to Tangshu Yu, or that his son, at the latest, produced it. The inscription calls its commissioner by the seniority term shu in combination with a personal name, suggesting that, in the context described in the inscription, the commissioner’s seniority status within his generation needed more emphasis than the specific lineage to which he belonged. This would surely have held true for a scion of the royal house.Footnote 31 The Shu Ze fangding inscription thus exemplifies the utility of ancestral rites for managing relationships in the political context of the early Western Zhou. The occasion of the entreaty and associated devotions helped motivate Shu Ze, likely a member of the Jin ruling line and descendant of the Zhou royal line, to attend the king at Chengzhou. This in turn let the king reinforce bonds with his kinsman through gifts of prestige goods, while situating those bonds within the hierarchical relations between king and retainer.

Another bronze shows that King Cheng conducted hui in the Zhou heartland as well:

唯成王大![]() ,才(在)宗周,商(賞)獻侯囂Footnote 32貝,用乍(作)丁侯

,才(在)宗周,商(賞)獻侯囂Footnote 32貝,用乍(作)丁侯![]() 彝。〔

彝。〔![]() 〕。

〕。

When King Cheng conducted a great entreaty at Zongzhou, [he] awarded cowries from Xiao to the Lord of Xian.Footnote 33 [The Lord] therewith makes an offering vessel for Lord Ding.

Unfortunately, the identity of Xianhou (translated here as “the Lord of Xian”) and the location of the state Xian 獻, if indeed it existed, are unclear.Footnote 35 Xianhou appears to have been of Shang cultural affiliation, judging from the use of the clan mark ![]() , common on Shang bronzes, and the ganzhi designation ding 丁 referring to the vessel dedicatee.Footnote 36 The format of the dedicatee’s name, Dinghou, affords the possibility that the Xian in Xianhou might not indicate the location of the bearer’s state, as was usual for an “X hou”-format name. Without further information on a potential state of Xian, it is hard to understand the relationship between Xianhou and the Zhou king. However, Xianhou’s apparent Shang heritage, combined with the fact that Xian is absent from the Zuozhuan’s list of Ji-surnamed regional states founded during the early Western Zhou, suggests that the two did not share patrilineal blood ties.Footnote 37 Xianhou was probably an important ally of the royal house, since his title, hou 侯, was carried by certain regional lords. Here again, then, in the context of an entreaty to royal ancestors, the king awards largesse to an aristocrat of high rank. The inscription again records no specific service rendered to the king, implying an assumed right to the king’s patronage.

, common on Shang bronzes, and the ganzhi designation ding 丁 referring to the vessel dedicatee.Footnote 36 The format of the dedicatee’s name, Dinghou, affords the possibility that the Xian in Xianhou might not indicate the location of the bearer’s state, as was usual for an “X hou”-format name. Without further information on a potential state of Xian, it is hard to understand the relationship between Xianhou and the Zhou king. However, Xianhou’s apparent Shang heritage, combined with the fact that Xian is absent from the Zuozhuan’s list of Ji-surnamed regional states founded during the early Western Zhou, suggests that the two did not share patrilineal blood ties.Footnote 37 Xianhou was probably an important ally of the royal house, since his title, hou 侯, was carried by certain regional lords. Here again, then, in the context of an entreaty to royal ancestors, the king awards largesse to an aristocrat of high rank. The inscription again records no specific service rendered to the king, implying an assumed right to the king’s patronage.

One further early Western Zhou inscription, duplicated on the Yu gui 圉簋 (3824–3825), the Yu yan 圉甗 (00935), and the Yu you 圉卣 (5374), records the king’s rewarding of an elite in the context of a hui-entreaty with no additional context:Footnote 38

王![]() 于成周,王易(賜)圉貝,用乍(作)寶

于成周,王易(賜)圉貝,用乍(作)寶![]() 彝。

彝。

The king conducted an entreaty at Chengzhou. The king awarded Yu cowries. [Yu] therewith makes a precious offering vessel.

The Yu vessels were recovered in the 1970s from tomb M253 in the Yan 燕 state cemetery at Liulihe, Fangshan, Beijing (with the exception of Yu gui no. 1 [3824], which had reputedly found its way to a tomb at Kazuo county, Liaoning province).Footnote 40 Given the size of tomb M253 and the richness of its grave goods, we can surmise that Yu wielded substantial influence in the early Western Zhou political world – probably as a scion of the Yan state’s ruling line.Footnote 41 Again, the Yu inscriptions record the bare fact of an influential figure attending a royal entreaty – potentially the same one recorded on the Shu Ze fangding – without additional justification. In this case, since the state of Yan lay in the far northeast of the Zhou sphere of influence, the attendee would have had to travel across most of north China to take part.Footnote 42

Hui-entreaties provided political opportunities and responsibilities for elites of lesser status as well. The indirect nature of the rewards they produced spurred greater elaboration in two early Western Zhou inscriptions – the Yu jue 盂爵 (9104) and the Shu gui 叔簋 (4132). The Yu jue, a bronze liquor cup probably dating to the reign of King Kang, records that the Zhou king dispatched a representative to the state of Deng, probably in modern Henan:Footnote 43

隹(唯)王初![]() 于成周,王令盂寧

于成周,王令盂寧![]() (鄧)白(伯),賓(儐)貝,用乍(作)父寶

(鄧)白(伯),賓(儐)貝,用乍(作)父寶![]() 彝。

彝。

When the king first conducted an entreaty at Chengzhou, the king ordered Yu to pacify the Elder of Deng. [Yu] received a guest-gift of cowries. [Yu] therewith makes a precious offering vessel for [his] father[s].

In this case, the initial contact between the vessel commissioner and the king took place in the context of the entreaty event, while the party to whose service the commissioner was assigned later granted an award. Yu, it would seem, did not receive a royal gift directly at the entreaty. However, the occasion precipitated the king assigning Yu to a lucrative position and so was duly recorded in the inscription.

Another two bronzes of probable early Western Zhou date, the two Shu gui 叔簋 (4132–4133), record the queen’s involvement in an interaction between elites on the occasion of a hui rite.Footnote 44 During a royal entreaty at Zongzhou, Shu received the queen’s command to attend the Grand Protector, whose vital role in the early Western Zhou state is well known.Footnote 45 The generous reward that Shu subsequently received came from the Grand Protector rather than directly from the queen; by thanking the Grand Protector in the vessel’s dedication, Shu makes that clear. However, the inscription still records the royal hui rite as the origin point of the interaction.

During the early Western Zhou, then, the Zhou royal house conducted high-profile hui-entreaties that served as venues for negotiating and maintaining political relationships with individuals of varying status. These took place at the key centers of Zhou power – Zongzhou; the capitals of Feng/Hao in the Zhou heartland; and Chengzhou, the recently founded eastern capital.Footnote 46 High-ranking Zhou aristocrats such as Shu Ze 叔夨, the Lord of Xian 獻侯, and Yu 圉 traveled substantial distances to attend. Powerful elites received largesse directly from the king, with no justification given in relevant inscriptions. Their right to attend the royal hui-entreaties was apparently implicit, although the rewards they received still warranted producing inscribed bronzes. Royal hui-entreaty also created opportunities for lesser elites such as Yu 盂 and Shu 叔 to earn recognition and rewards, which they then recorded on inscribed bronzes, leveraging them for status and prestige in the context of their individual lineage cults. The practice of hui-entreaty during the early Western Zhou thus helped the kings shore up the infrastructure of their recently formed state.

After the early Western Zhou, the Zhou kings seem to have performed hui-entreaty less, or at least under less high-profile conditions. Only the inscriptions of the Hu gui and the Bu Zhi fangding attest to royal hui after that point. Based on this, Liu Yu has characterized the early Western Zhou as the “golden age” of hui-entreaty among the Zhou.Footnote 47 If we account for inscriptions recording concern with hui among nonroyal elites, however, the custom seems to have enjoyed its heyday during the middle Western Zhou period and survived throughout the Western Zhou era. Hui is virtually absent from received texts, however, as well as from bronze inscriptions dating to the middle Spring and Autumn period and later. Given the centralized distribution of bronzes that claim it as a purpose, it is likely that the term hui, if not the custom it described, was conceptually associated with the political influence of the Zhou kings. As their importance as arbiters of prestige faded, the term hui likewise receded from the historical record.

Zheng 烝/蒸 (Deng 登)

The bronze inscriptions contain several instances of the approximate character form ![]() , alternately transcribed as zheng 烝, zheng 蒸, deng 登, and deng 鄧 depending on the transcribers’ sense of its meaning.Footnote 48 Like most of the terms considered here, zheng/deng came to the Zhou from the Shang, among whom it designated a practice that included offering either foodstuffs or liquor to ancestors, but may also have involved mustering troops or large groups of personnel.Footnote 49

, alternately transcribed as zheng 烝, zheng 蒸, deng 登, and deng 鄧 depending on the transcribers’ sense of its meaning.Footnote 48 Like most of the terms considered here, zheng/deng came to the Zhou from the Shang, among whom it designated a practice that included offering either foodstuffs or liquor to ancestors, but may also have involved mustering troops or large groups of personnel.Footnote 49

Royal Performances of zheng

Records of the Zhou king performing a ritual act referred to as zheng 蒸 survive from throughout the period. The earliest – putatively, at least – appears in the inscription of the Da Yu ding 大盂鼎 (2837), one of the longest and most detailed from the early Western Zhou period.Footnote 50 Most of its length records a royal speech given when the king appointed a figure named Yu, who had helped educate the king, to a new office and granted him lavish rewards.Footnote 51 As a lead-in to this speech, the king assessed the accomplishments of Kings Wen and Wu. Among the latter’s good points, we are told, was his temperance when performing actions called 髭 and ![]() ; the latter is certainly zheng 蒸.Footnote 52 The account offers no further details, but it is notable that (1) the current king held that King Wu had performed zheng, and (2) zheng was, when this inscription was composed, seen as a process in which consumption, and perhaps over-consumption, of liquor might be expected.Footnote 53

; the latter is certainly zheng 蒸.Footnote 52 The account offers no further details, but it is notable that (1) the current king held that King Wu had performed zheng, and (2) zheng was, when this inscription was composed, seen as a process in which consumption, and perhaps over-consumption, of liquor might be expected.Footnote 53

The most concrete example of royal zheng from the early Western Zhou appears in the inscription of the Gao you (5431) (Figure 1.3), known only from Song dynasty collections:Footnote 54

〔亞〕。隹(唯)十又二月,王初![]() 旁,唯還在周,辰才(在)庚申,王酓(飲)西宮,

旁,唯還在周,辰才(在)庚申,王酓(飲)西宮, ![]() (蒸)。咸,釐尹易(賜)臣雀僰 Footnote 55揚尹休,高對乍(作)父丙寶

(蒸)。咸,釐尹易(賜)臣雀僰 Footnote 55揚尹休,高對乍(作)父丙寶![]() 彝,尹其亙萬年受氒(厥)永魯,亡競才(在)服,

彝,尹其亙萬年受氒(厥)永魯,亡競才(在)服, ![]() 長𠤕其子子孫孫寶用。

長𠤕其子子孫孫寶用。

(Ya.) It was the twelfth month, when the king first feasted at Pang. When he returned to Zhou, on the gengshen day, the king hosted drinking at the Western Palace and performed zheng. When it was finished, Chief Li gave his servant a spotted(?) canopy.Footnote 56 Praising the Chief’s beneficence, Gao, in response, makes a precious offering vessel for Father Bing. May the Chief continue for ten thousand years to confer his eternal brilliance, without peer in service. May the descendants of Zhi, the head of the Ji, treasure and use [it].Footnote 57

The prestation relationships recorded here were complex. The Zhou king held a drinking event and associated zheng-offering that occasioned a gift to Gao. The king did not, however, give this gift; instead, it came from a figure called “the Chief” (yin 尹). Gao then praised the Chief’s beneficence, designating him as the significant patron for purposes of the gift. Gao went on to cast the Gao you for Father Bing, commemorating the reward in the context of his ancestral cult and referring to the Chief near the end of its inscription. The final clause, however, commits the vessel to the use of the descendants of “Zhi, the head of the Ji” (Ji zhang Zhi ![]() 長𠤕). Based on the location of its appearance, this phrase probably refers to Gao himself, but that is not certain.Footnote 58

長𠤕). Based on the location of its appearance, this phrase probably refers to Gao himself, but that is not certain.Footnote 58

It is difficult to decipher the relative status of the various parties mentioned based on the Gao you inscription alone. In all likelihood, the Chief was a subordinate of the king who took part in the drinking event and the zheng-offering, and perhaps the preceding feast as well.Footnote 59 The “servant” (chen 臣) whom the Chief rewarded, presumably the vessel commissioner Gao, may have been the Chief’s subordinate or, alternatively, a royal functionary whom the king tasked the Chief to reward. He may have played a role in the drinking event and the zheng-offering, or simply have been present at the time and reaped the benefits. This may or may not have been a redistribution of a corresponding reward given by the king to the Chief. We can state with certainty only that the king hosted a drinking event that included an instance of zheng, and that occasion created a context for the Chief to reward a subordinate who commissioned an inscription to commemorate the occasion. It is perhaps also notable that the king’s event was a drinking party, hinting at a connection between zheng and liquor. That the vessel bearing this inscription, according to Bogu, was of a type normally used to hold alcoholic beverages may be obliquely relevant.Footnote 60

This royal performance of zheng was part of a prestation event instantiating multidirectional bonds of patronage. Gao owed thanks to the Chief for his gift, but that gift came, if not from the king himself, at least due to the Chief’s service to the royal house. In his inscription, Gao recorded the royal activities that formed the context of the gift and entreated the Chief’s continued service, locating the Chief within the state hierarchy and emphasizing his own connection to the king through the Chief. The gift thus further bound the Chief to the royal house, since his subordinate recognized the Zhou king as the source of the Chief’s ability to confer gifts.

The inscription of the Duan gui 段簋 (4208), an unprovenanced middle Western Zhou vessel held by the Shanghai Museum, records another zheng performed by the Zhou king.Footnote 61 The offering in the Gao you inscription took place on the king’s home ground at Zongzhou. Here, by contrast, the king conducted a zheng-offering at Bi – a location important to the royal house, but apparently also the territory of another lineage.Footnote 62 The multiday event of the king’s visit included both the zheng-offering and a recounting of merits for Duan, the vessel’s commissioner. During the latter process, the king recalled the lineage of a figure named Bi Zhong, presumably an ancestor of Duan’s, suggesting that Duan was related to an elite lineage with authority over the area.Footnote 63 The king then ordered another figure called Long Ge 龏𢦚 to make a great apportionment of land to Duan.Footnote 64 As no further details are offered on Long Ge, it is unclear whether he was local or traveled to Bi along with the king. However, since Duan thanked the king, rather than Long Ge, for the honors conveyed, it appears that Long Ge was a functionary rather than an active agent in the transaction.

Here, as in the Gao you case, the royal performance of zheng formed part of a wider ritual event that included rewarding subordinate elites. In this case, however, it took place on the home ground of the recipients. The king’s visit, zheng ceremony, recounting of merits, and accompanying reward thus comprised a direct royal intervention in the local hierarchy through the medium of ritual.Footnote 65

Nonroyal Vessels Cast for Zheng-Offering

Two vessels commissioned by nonroyal elites and dating to the second half of the Western Zhou – the Taishi Cuo dou 大師虘豆 (4692) and the Ji ding 姬鼎 (2681) (Figure 1.4) – declare zheng as the purpose of their creation.Footnote 66 Both are food vessels, contrasting with the admittedly weak association of zheng with liquor in early inscriptions. Both also indicate that the zheng in question would be devotions to patrilineal ancestors; though this likely held for the early, royal cases as well, the relevant inscriptions lack evidence to that effect.Footnote 67 The Ji ding was almost certainly made to support the ritual activities of a married woman on behalf of her husband’s patriline.Footnote 68 The combination of the terms zheng and chang in its inscription, in the phrase 用![]() (烝)用嘗 yong zheng yong chang (“therewith to perform zheng-offering and chang-offering”), is the first occurrence of a formula that sees use in later inscriptions, and of an association that recurs in the later ritual texts.Footnote 69

(烝)用嘗 yong zheng yong chang (“therewith to perform zheng-offering and chang-offering”), is the first occurrence of a formula that sees use in later inscriptions, and of an association that recurs in the later ritual texts.Footnote 69

Figure 1.4 The Ji ding.

By the late Western Zhou, then, a model of zheng had emerged among nonroyal elites that involved offering foodstuffs to patrilineal ancestors in search of longevity and other blessings. Providing for these lineage cult activities was itself apparently sufficient justification for creating an inscribed bronze.

Zheng in Received Texts

Zheng is relatively common in received texts of possible Western Zhou date. As a term for an offering, it appears in two Shijing songs, “Feng nian” and “Zai shan,” classified as “Zhou Hymns.”Footnote 70 Both describe agricultural activities and their relationship with the envisioned Zhou social order, with ancestral devotions as an organizing principle. As befits its name, “Feng nian” covers only the harvest side of the equation. “Zai shan” is much longer; it gives a full and idealized account of the agricultural process, celebrating the rustic virility of the cultivators and arguing for the antiquity of the agricultural cycle and concomitant devotional activities. The part of the poem describing the harvest, however, is almost identical to the corresponding lines in “Feng nian”:

Making liquor, making sweet wine, for zheng and giving to ancestors and ancestresses, in accordance with the hundred rites … (Zai shan)Footnote 71

The poems specify quite clearly that the grains of the harvest will produce alcoholic beverages, which will then support the performance of zheng rites to patrilineal ancestors and ancestresses.Footnote 72 The designation of liquor for zheng is of note, echoing the association between the two in relevant early Western Zhou inscriptions.Footnote 73 The poems describe zheng as, if not a harvest rite, at least one that took place after the fruits of the harvest had been processed into spirits. They mention no special association with the royal house; there is no reason these poems might not have been performed in any Zhou elite household.

A relevant passage from the Shangshu offers less detail on zheng per se but more on its use in a royal ritual event. The “Luo gao” chapter narrates the ceremonies surrounding the establishment of the eastern Zhou capital at Chengzhou. The question of the appropriate role of the king – direct governor or ritual head of state – permeates the passage, thanks to its concern with King Cheng and the Duke of Zhou.Footnote 74 As such, the narrative contains several significant terms relating to Zhou ritual. One portion describes a series of offerings conducted when King Cheng assigned the Duke of Zhou to handle affairs at Chengzhou:Footnote 75

On the wuchen day, at the New City (Xinyi), the king performed zheng-sacrifice.Footnote 76 He presented one red ox to King Wen and one red ox to King Wu in sui-offering. The king ordered Document Maker Yi to perform an invocation with documents, announcing that the Duke of Zhou would remain behind.Footnote 77 The king acted as [ritual] guest; he killed (the sacrificial victim). When the offering was complete, he entered.Footnote 78 The king entered the Great Hall (Taishi 太室) and performed guan-libation. The king commanded the Duke of Zhou to remain behind; Document Maker Yi made the announcement. It was the twelfth month, when Dan, the Duke of Zhou, preserved the command received by Kings Wen and Wu; it was the seventh year.Footnote 79

The king’s zheng accompanied but was not equivalent to his sui-offering 歲, in which he offered one red ox each to his father and grandfather. These acts, as well as an offering called yin 禋, took place outside the complex containing the Great Hall (Taishi 太室) – presumably because, as the passage specifies, the sequence involved the king killing the sacrificial victims. Along with them, an official with the title “Document Maker” (Zuoce 作冊) performed an invocation at the king’s behest, perhaps relating to the king’s upcoming command to the Duke of Zhou.Footnote 80 When finished, the king proceeded inside to perform guan-libation and issue the official announcement, through the intermediary Document Maker Yi, that the Duke of Zhou would remain behind in Chengzhou. The individual offering zheng here is just one component of an extended ritual sequence. Many of the surviving accounts of early Western Zhou royal ritual are like this; Chapter 4 of this work explores the implications of this fact in greater detail.

Zhu 祝 (Invocation)

Inscriptions from throughout the Western Zhou contain zhu 祝, a term with precedent in the Shang oracle bones, which the Han-era Shuowen jiezi – a much later source – defines as “when the master of a ritual speaks words of praise” (ji zhu zan ci zhe 祭主贊詞者), and which is sometimes translated as “Invoker” or “Invocator.”Footnote 81 Two points from received texts support understanding zhu in this sense in the Western Zhou sources. The “Luo gao” chapter of the Shangshu records that King Cheng, as part of a series of offerings, orders Document Maker Yi (Zuoce Yi 作冊逸) to perform a zhu 祝 with documents relating to the Duke of Zhou’s subsequent assignment.Footnote 82 In the “Ke Yin” chapter of the Yizhoushu, the term serves as part of the title “Temple Invoker” (zongzhu 宗祝), a figure whom the leader of the Zhou orders to honor important guests and conduct prayers among the Zhou troops after the conquest of Shang.Footnote 83 Together, these texts offer intriguing though inconclusive evidence that the relevant Western Zhou inscriptions might have meant by zhu something close to “invocation” or “Invoker.”

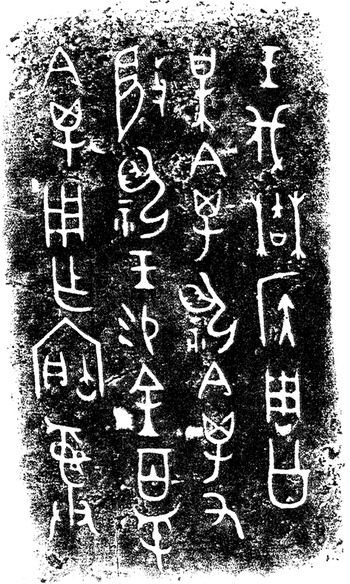

Only two Western Zhou inscriptions use the term zhu for actual occurrences of a ritual technique. Chapter 4 discusses one of these, the Xiao Yu ding inscription, in detail; here we may simply note its claim that the king personally performed an invocation as part of a series of ritual events.Footnote 84 The second is the Qin gui 禽簋 (4041) inscription (Figures 1.5 and 1.6), dating probably to the reign of King Cheng and famed for mentioning the Duke of Zhou and his eldest son, Qin:Footnote 85

王伐![]() (蓋)侯,周公某(謀),禽祝,禽又(有)敐祝,王 易(賜)金百

(蓋)侯,周公某(謀),禽祝,禽又(有)敐祝,王 易(賜)金百![]() (鋝),禽用乍(作)寶彝。

(鋝),禽用乍(作)寶彝。

The king attacked the Marquis of Gai. The Duke of Zhou did the planning. Qin performed an invocation (zhu). Qin had a full-vessel invocation.Footnote 86 The king presented [Qin] with one hundred lüe of metal. Qin thereby makes a precious vessel.

Qin’s invocation is part of the preparations for the king’s campaign, the ritual counterpart to his father’s planning. It is tempting to see the division of responsibilities between the Duke of Zhou and his son Qin as part of the Duke’s controversial domination of the Western Zhou government during King Cheng’s earlier years, stipulated in the classic historical narratives of the time.Footnote 87 Indeed, Qin held the official title of “Grand Invoker” (Dazhu 大祝), as we know from the inscription of the Dazhu Qin ding 大祝禽鼎 (1937–1938).Footnote 88

Figure 1.6 The inscription of the Qin gui.

Three more inscriptions commemorate the appointment of Zhou elites as either “Invokers” (zhu 祝) – an official position that persisted, in various locations and at various levels, throughout the Western Zhou period – or as aides to such.Footnote 89 The Shen guigai (4267), a middle Western Zhou vessel, records Shen’s appointment to assist the “Grand Invoker” (da zhu 祝 ). Since his responsibilities included supervising a group known as the “Invokers of the Nine Xi” (jiu xi zhu 九![]() 祝), one can reasonably assume that Shen carried the title of Invoker as well.Footnote 90 Notably, the inscription specifies that Shen is succeeding his father and grandfathers in this role, suggesting that his lineage had a family tradition of service as Invokers. The inscription of the Chang Xin he (9455), another middle Western Zhou vessel, describes a Grand Invoker’s participation in a formal archery competition; since this Grand Invoker shot in a pair with the influential Elder of Jing (Jingbo), it stands to reason that his status at court was quite high.Footnote 91 Finally, the Qian gui (4296–4297), a late Western Zhou vessel, commemorates the king extending its commissioner’s appointment as Invoker for the Five Cities, and the beginning portion of the inscription specifically refers to Qian as “Invoker Qian.”Footnote 92 By the middle to late Western Zhou at the latest, it seems, the office of Invoker had developed both an internal hierarchy of ranks and hereditary associations with particular lineages.

祝), one can reasonably assume that Shen carried the title of Invoker as well.Footnote 90 Notably, the inscription specifies that Shen is succeeding his father and grandfathers in this role, suggesting that his lineage had a family tradition of service as Invokers. The inscription of the Chang Xin he (9455), another middle Western Zhou vessel, describes a Grand Invoker’s participation in a formal archery competition; since this Grand Invoker shot in a pair with the influential Elder of Jing (Jingbo), it stands to reason that his status at court was quite high.Footnote 91 Finally, the Qian gui (4296–4297), a late Western Zhou vessel, commemorates the king extending its commissioner’s appointment as Invoker for the Five Cities, and the beginning portion of the inscription specifically refers to Qian as “Invoker Qian.”Footnote 92 By the middle to late Western Zhou at the latest, it seems, the office of Invoker had developed both an internal hierarchy of ranks and hereditary associations with particular lineages.

In the early Western Zhou, then, the king could perform zhu-invocation but could also appoint official personnel to do so. Middle and late Western Zhou inscriptions attest to an expansion of such personnel. The title of Grand Invoker, once held by Qin, survived into the middle Western Zhou at least, and lesser offices were created as well. Some were known simply as “Invoker,” while others, such as “Invoker of the Five Cities” and “the Invokers of the Nine Military Camps,” were identified with specific locations, extending the royal ritual model across the Zhou cultural sphere.

Invocations place the performer at the center of attention during important public events. At a time when state-level public appearances required an enormous investment in time and resources, an official appointment to make them regularly would have offered substantial prestige. It is unsurprising, then, that the institutional underpinnings of zhu-invocation expanded over the course of the period. Pressure on the royal house to afford powerful elites and their scions the prestige and public visibility of invocation must have been great. At the same time, selecting invokers would have been a powerful tool for soliciting the loyalty of lesser elites, developing them as resources with recognition and connections among the community, and establishing an alternative to the context of military endeavor that supported much of early Western Zhou patronage.Footnote 93

Post–early Western Zhou inscriptions contain no references to specific performances of zhu. Judging, however, from the detailed references in received texts from the Eastern Zhou and Han periods, we can safely say that the practice of zhu-invocation achieved traction throughout the Zhou cultural sphere and survived throughout the pre-Qin period.Footnote 94 Probably, then, the expansion of officially designated Invokers was accompanied by continued practice of invocation throughout the Western Zhou state, and the lack of references to specific invocations in middle and late inscriptions reflects not an overall waning of the practice, but changes in the royal practice of ritual and its relationship to the casting of inscribed bronzes.

Livestock Offerings and Royal Patronage

Sacrifice of livestock animals was a central feature of early Chinese ritual from the earliest reaches of recorded history down through the creation of the ritual canon. Indeed, inquiries about the proper type, number, and timing of livestock sacrifices loom large in the Shang oracle bones, the earliest extant written records in China.Footnote 95 Sacrificial offerings were among the aspects of Shang ritual that the Zhou kings continued, and traces of their use made their way into the inscriptions of bronzes. These accounts offer little detail on the technical aspects of sacrifice, but they have much to say about the social relations that sacrificial offerings helped to create, maintain, and modify.

In the Western Zhou inscriptions, the two ritual techniques di/chi 禘/啻 and lao 牢/da lao 大牢 both involved livestock offerings. A close look at their records in the inscriptions will shed some light on how the Zhou kings’ investment in livestock sacrifice, as both performers and patrons, helped tie together the Zhou elite community.

Chi 啻 (Di 禘?)

The Western Zhou bronze inscriptions record four instances of a ritual action designated chi 啻 – that is, the base character di 帝 over a mouth radical or other square object 口. Analyses of this term sometimes approach it as an intermediary stage between di 帝, used by the Shang for both the greatest known spirit and a rite performed for a variety of ancestor spirits and natural phenomena;Footnote 96 and di 禘, characterized in the Liji as a seasonal rite exclusive to the Zhou royal house.Footnote 97 Judging from bronze inscriptions, however, the Western Zhou rite that this character designated shared little with either the Shang di 帝 rite that preceded it or the di 禘 rites described in Eastern Zhou and Han sources.Footnote 98 Instead, the inscriptions depict a nonexclusive livestock rite that made up a key part of Western Zhou elite patronage.

The earliest case, appearing in the Xiao Yu ding 小盂鼎 (2839) inscription, formed part of an elaborate, multiday ritual event. In the wake of a great military victory, the vessel commissioner Yu attended the king – probably King Kang – at the Zhou Temple (Zhou miao 周廟) together with some of the most powerful individuals in the Zhou state.Footnote 99 As part of the recognition of his accomplishments, Yu witnessed a di/chi 啻 offering that the king performed, targeting the previous kings Wu and Cheng as well as a figure called “the Zhou King”; the latter presumably referred to King Wen as founder of the Zhou state.Footnote 100 The offering involved a livestock sacrifice (sheng 牲) and was connected with a number of libations (guan 祼) exchanged between the aristocratic participants, as well as a crack-divination (bu 卜) and an invocation (zhu 祝) performed by the king himself. The king presented Yu with several gifts on this occasion.Footnote 101

Further occurrences of the di/chi offering appear in several brief inscriptions dating to the middle Western Zhou period. Read together, they offer an intriguing network of data on the circumstances of the rite and its role in elite relations. The Xian gui (10166), for example, also records the king’s formal acknowledgment of a subordinate in conjunction with a di/chi offering to a prior king – in this case, King Zhao.Footnote 102 Liquor and liquor vessels figured importantly in the process; not only did the honoree Xian take part in guan-libations, but the king also awarded him jade tools for conducting them. This also recalls the Xiao Yu ding inscription narrative, which, though incomplete, describes even more elaborate exchanges of libations between honoree, king, and attendees.

The La ding 剌鼎 (2776), another probable King Mu vessel,Footnote 103 suggests that its dedicatee played an active role in the king’s di/chi rite:

唯五月王才(在)衣, 辰才(在)丁卯,王啻(禘),用牡于大室,啻(禘)卲(昭) 王,剌![]() (御), 王易(賜)剌貝卅朋, 天子邁(萬)年,剌對揚王休, 用乍(作)黃公

(御), 王易(賜)剌貝卅朋, 天子邁(萬)年,剌對揚王休, 用乍(作)黃公![]() 彝,

彝, ![]() (其)孫孫子子永寶用。

(其)孫孫子子永寶用。

It was the fifth month; the king was at Yi. On the day dingmao, the king conducted the di-rite. He employed a sacrifice in the Great Hall and performed the di-rite for King Zhao; La attended [on the king]. The king presented La with thirty strings of cowries. Ten thousand years to the Son of Heaven! La praises the king’s beneficence in response, thereby making a precious jiang-vessel for Huanggong. May [his] grandsons’ grandsons and sons’ sons long treasure and use [it].

In fact, the La ding inscription is the only example in which the di/chi rite does not coincide with a ceremonial acknowledgment of merit. It is of course possible that no such acknowledgment occurred in this case. However, the term yu 御, rendered here as “to attend on,” indicates that La was not a passive guest, but played a supporting role in the rite.Footnote 104 This suggests that the gift La received was meant to reward his help with the rite itself. If an acknowledgment of merit did occur, La may have omitted it as irrelevant to his case; alternatively, the cowries may simply have been meant as a hospitality gift for La.

The aforementioned inscriptions comprise all cases in which the king is said to have performed a di/chi rite. Other Zhou aristocrats did so as well, however. The inscription of the Fan you 繁卣 (5430), dated by the AS database to the middle Western Zhou, provides an example:Footnote 105

隹(唯)九月初吉癸丑,公![]() 祀,

祀,![]() 旬又一日辛亥,公啻(禘)

旬又一日辛亥,公啻(禘)![]() 辛公祀,卒事亡

辛公祀,卒事亡![]() ,公

,公![]() (蔑)繁𤯍,易(賜)宗彝一

(蔑)繁𤯍,易(賜)宗彝一![]() (肆)、車、馬兩。繁拜手

(肆)、車、馬兩。繁拜手![]() 首,對揚公休,用乍(作)文考辛公寶

首,對揚公休,用乍(作)文考辛公寶![]() 彝,其邁(萬)年寶。〔或〕。

彝,其邁(萬)年寶。〔或〕。

It was the ninth month, the chuji moon phase, the guichou day. The Duke performed ![]() -offerings. Eleven days later, on the xinhai day,Footnote 106 the Duke performed a di/chi offering and a

-offerings. Eleven days later, on the xinhai day,Footnote 106 the Duke performed a di/chi offering and a ![]() -offering to Duke Xin. The business was completed without harm. The Duke recounted Fan’s merits, giving [him] a vessel for the ancestral hall,Footnote 107 a chariot, and two horses. Fan bows and strikes his head, praising the Duke’s beneficence in response, therewith making a precious offering vessel for [his] cultured deceased father Duke Xin. May [he] treasure [it] for ten thousand years. [Emblem]

-offering to Duke Xin. The business was completed without harm. The Duke recounted Fan’s merits, giving [him] a vessel for the ancestral hall,Footnote 107 a chariot, and two horses. Fan bows and strikes his head, praising the Duke’s beneficence in response, therewith making a precious offering vessel for [his] cultured deceased father Duke Xin. May [he] treasure [it] for ten thousand years. [Emblem]

Here again, the vessel commissioner, Fan, receives the mieli acknowledgment in conjunction with a di/chi rite. In this case, however, the performer was not the king, but a person known by the title gong 公. Given that the rite in question targeted a certain Xingong 辛公 and that Fan dedicated his vessel to the same figure, it is likely that Fan was a blood relative of the dedicatee, perhaps a younger brother or member of a branch lineage connected with the main lineage through Duke Xin. The Duke awarding an ancestral vessel (zongyi 宗彝) to Fan exemplifies the direct promulgation of ancestral ritual. The Duke rewards Fan for playing the appropriate role in the former’s ancestral cult, while also providing him with the tools to conduct his own cult activities. Here, then, is a case of the active structuring of the lineage hierarchy through ritual participation.

Based on later texts, one might imagine that the Duke, by performing di/chi, co-opted a royal prerogative.Footnote 108 The inscription of the Da gui大簋 (4165) (Figures 1.7 and 1.8), however, shows that the royal house intended for others to perform the rite:

唯六月初吉丁巳,王才(在)奠Footnote 109(鄭),𥣫(蔑)大𤯍,易(賜)芻![]() (騂)

(騂)![]() (犅),曰:用啻于乃考。大拜𩒨首,對揚王休,用乍(作)𦨶(朕)皇考大中(仲)

(犅),曰:用啻于乃考。大拜𩒨首,對揚王休,用乍(作)𦨶(朕)皇考大中(仲)![]()

![]() 。

。

It was the sixth month, the chuji moon phase, the dingsi day; the King was at Zheng and recounted Da’s merits, awarding him red, grain-fed livestock and saying, “Use this in di/chi-offering to your deceased father.” Da bowed and struck his head, praising the king’s beneficence in response, therewith making a gui-tureen for offerings for my august deceased father Da Zhong.Footnote 110

In this case, the king is in Zheng, outside the normal sphere of his ritual activities; he is probably on the home ground of the Da lineage.Footnote 111 He conducts the recounting of merits for Da and arranges an award of cattle raised on fodder, stipulating their use as offerings in a di/chi rite to Da’s patrilineal ancestors. Although the king himself does not perform an offering, he does take pains to associate the acknowledgment of Da’s merits with ancestral ritual by ensuring that Da is equipped to carry on the rite on his own time.

Royal support of di/chi seen here reinforced the association of the patrilineal ancestral cult with the prestige derived from connections with the Zhou royal house. Da could conduct the di/chi rite with auspicious offerings thanks to the largesse he received in conjunction with his official acknowledgment of merits. Performing the offerings within his own ancestral cult would then recall his relationship with the king. The Zhou kings thus tethered the internal relationships of Da’s lineage to external relationships (i.e., Da’s standing with the Zhou royal house).Footnote 112 The fact that the kings had themselves performed the di/chi rite that Da was to perform would have reinforced this connection, as would Da commissioning an inscribed bronze commemorating his receipt of the livestock for the offering. The normative force of these connections would, of course, have been contingent on Da’s actual performance of the rite as requested. It is possible that Da simply accepted the king’s gift with good grace and went about his business. Still, the example of the Fan you indicates that at least some Zhou aristocrats found the di/chi rite relevant enough to carry out independent of the king’s immediate supervision; and Da recording the sequence on an inscribed bronze suggests that he introduced at least the idea of royally sponsored di/chi into the context of his lineage cult.

The Bamboo Annals and the Chronology of Di/Chi

These examples comprise all direct references to di/chi 啻 as a rite in the Western Zhou inscriptions. However, the “New Text” section of the Bamboo Annals contains two references to a rite under the name di 禘. One, dated to King Cheng’s reign, notes that representatives of the state of Lu 魯 performed it at the Temple of the Duke of Zhou after a successful campaign with the king.Footnote 113 The other targeted “the former kings” (xian wang 先王) and is attributed to King Kang.Footnote 114 As public ancestral rites, recorded as major events and performed by both the Zhou king and the representatives of a powerful branch lineage, these are compatible with the image of chi 啻 presented in the bronze inscriptions. The Bamboo Annals account, if one takes it seriously, thus offers some oblique evidence that early authors saw the term di/chi 啻 in the Western Zhou bronzes as related to the term di 禘.Footnote 115

Di/Chi and Zhou Politics

The ritual technique di/chi 啻 was used during the early and middle Western Zhou periods; three inscriptions mentioning it probably date to the reign of King Mu. The Zhou kings performed it occasionally as part of major ceremonial events, but other powerful Zhou elites used it as well, with the blessing of the Zhou royal house.Footnote 116 It involved, or at least admitted, a livestock sacrifice and frequently took place in conjunction with guan-libations. The Zhou kings performed it in multiple locations at different times. Typically, however, it went along with an official recounting of a subordinate’s merit, providing an opportunity to instantiate hierarchical bonds between superior and subordinate in the context of patrilineal ancestral ritual.

Rewarding elites who assisted with the ritual event, as in the La ding inscription, extended patronage opportunities beyond the individual relationship celebrated in the recounting of merit. This in turn would have encouraged a sense of cooperative well-being, as the ancestral rituals associated with the honoring of one created opportunities for others to distinguish themselves and receive rewards. Di/chi events thus encouraged elites to develop interdependent assignations of status within the rubric of Zhou elite interaction. To use Callon’s term, they strove to establish interessement, to engage different elites in forming the pearl of Zhou elite identity around the grain of sand that was ritual.Footnote 117

Lao 牢/Da Lao 大牢

As implied by its form, the character lao 牢 is generally understood in Shang and Western Zhou inscriptions to indicate pen-raised livestock animals or the sacrificial offering of such.Footnote 118 Only two inscriptions offer any potential evidence that the Zhou kings personally performed offerings called by that name. One, the Zi zun 子尊 (6000), may be of Shang rather than Western Zhou date; in its inscription, the term effectively functions as a measure word – albeit for animals to be used as victims in a specified rite.Footnote 119 In the second, that of the Haozi you 貉子卣 (5409) (Figures 1.9 and 1.10), lao probably means simply “to pen up [game],” as on a hunt.Footnote 120

Figure 1.9 The Haozi you. Unknown artist, China, 11th c. BCE, bronze. Minneapolis Institute of Art: bequest of Alfred F. Pillsbury, 50.46.94a, b.

Figure 1.10 The inscription of the Haozi you. Unknown artist, China. 11th c. BCE, bronze. Minneapolis Institute of Art: Bequest of Alfred F. Pillsbury, 50.46.94a, b.

Nonroyal elites certainly employed a sacrifice called lao, however, and higher-ranking or even royal patrons occasionally supported their efforts. Three more instances of the term lao occur among the inscriptions. All appear in the compound phrase da lao 大牢, “great penned livestock [offering],” seen commonly in both Shang oracle bones and later received texts.Footnote 121 The inscription of the Lübo gui (3979) offers some evidence that this phrase could describe an offering:

吕(呂)白(伯)乍(作)氒(厥)宮室寶![]() 彝

彝![]() ,大牢, 其萬年祀氒(厥)祖考。

,大牢, 其萬年祀氒(厥)祖考。

The Elder of Lü makes a precious sacrificial gui-tureen for his palace hall and [performs] a great lao-offering. May he make offerings (si 祀) to his grandfathers and deceased father for ten thousand years.

The Lübo gui is no longer extant; we know it from its line drawing and rubbing in Xiqing.Footnote 122 Duandai dates it to King Kang.Footnote 123 Judging from the apparent depth of the vessel, its facing-bird decorations, and its cover, however, the AS database is probably right to assign it to the middle Western Zhou.Footnote 124 The syntax of the inscription leaves little room for doubt that the da lao it records was an ancestral offering.Footnote 125

The remaining two vessels have both entered the corpus relatively recently. The Rong Zhong ding 榮仲鼎 (NA1567), probably dating to the early Western Zhou, was recently acquired by the Poly Museum.Footnote 126 It records that a party called Zi 子 conferred an honorary gift on Rong Zhong after the king created a structure for Rong Zhong that AS renders as gong 宮, “palace, office,” and Li identifies as xu 序, “school.”Footnote 127 This Zi may have been a royal scion; the son or sons of the Elder and the Lord of Hu; or perhaps even a powerful former Shang noble, as Liu Yu proposed for the Zi of the Zi zun inscription. After the gift, Rong Zhong issued invitations to the sons of the Elder of Rui (Ruibo 芮伯) and the Lord of Hu (Huhou 胡侯).Footnote 128 What brings the event to our attention here is that Zi’s gifts to Rong Zhong included sheng da lao 牲大牢, “a great lao for sacrifice.”

The sequence of this inscription suggests that the Zhou royal house set up physical infrastructure to support patronage, royal or otherwise, of Rong Zhong’s ancestral cult activities. After the king furnished a facility, Rong Zhong hosted elites from the lineages of Rui and Hu, drawing on the resources received from Zi to forge bonds with other powerful Zhou affiliates.Footnote 129 The da lao, the offering animals, in question let Rong leverage the facility built for him by the king to make inter-lineage connections, at once winning status for himself and strengthening the network of relations around which the Zhou state was organized. Zi then rewarded Rong Zhong yet again, providing him with metal to cast a bronze commemorating the event.

If Zi’s role in the Rong Zhong ding inscription raises questions about the connection of the royal house to the activities described therein, the inscription of the Ren ding 壬鼎 (NA1554), recently acquired by the Chinese National Museum, presents no such ambiguities.Footnote 130 It records that Ren’s merits were officially recounted by a representative of the king after a series of unusual circumstances.Footnote 131 Gifts, which again included a da lao meant expressly for sacrifice (the phrase used is ting sheng tai lao 脡牲太牢, “a great lao for meat-sacrifice”) accompanied the recounting.Footnote 132 In both of these inscriptions, then, an intermediary, rather than the king himself, conveyed gifts that included livestock offerings. We might attribute this to the convenience of delegating the management of animals to specialists, or to someone whose own herds were closer to the site of the gift; but the inscription of the Da gui, wherein the king personally conveys a reward of cattle for sacrifice, offers a counter-example.

No extant material confirms that any Western Zhou king performed an offering called lao. Most instances of the term describe gifts of livestock meant to support ancestral cult activities of other elites. The problematic Zi zun case, if we accept it as a Western Zhou vessel, describes the gift of livestock victims by an elite of potential Shang royal extraction to the king, for which he was well rewarded with a zan-jade – an important piece in the context of Western Zhou elite ornamentation – and a large volume of cowries. Through his support of royal sacrificial activities, he converted his agricultural wealth into a form denoting status within the Western Zhou sphere of elite interaction.Footnote 133 The Rong Zhong ding and Ren ding inscriptions, in contrast, record royal patronage of ancestral offerings performed by lesser elites. In the former inscription, Zi’s gift helps integrate Rong Zhong into a network of ranking Zhou elites, while also tying him directly to the king through royal patronage of his ancestral cult. The Ren ding inscription records a similar situation, though Ren seems already to have rendered the king special service. Both of these inscriptions bear clan marks and dedications employing tiangan funerary names, raising the possibility that lao or da lao, as of the middle Western Zhou, was seen as relating to Shang heritage; however, the Lübo gui inscription contains neither.

Whether or not the Zhou kings ever performed lao as understood under the Shang, they did recognize how useful sacrificial livestock victims could be as a vehicle of patronage, allowing them to exert influence through the ancestral cults of local elite lineages. The redistribution mechanism of feasting ensured that those bonds would reach throughout patronized lineages and potentially, as in the Rong Zhong ding case, horizontally to other powerful Zhou elites.

Early Western Zhou Ritual Techniques

Certain Shang-style techniques carried over into the early Western Zhou period but failed to achieve lasting traction as part of the basic toolkit of Zhou elite ritual. A close look at the inscriptional records of three such techniques offers a glimpse of how political and practical concerns affected the scope of ancestral-ritual practice.

Liao 燎 (Burnt Offering)

The practice of burning offerings is attested in prehistoric China, particularly near the east coast.Footnote 134 Chen Mengjia connected this to a proposed western migration of the Shang population.Footnote 135 Whether or not it had been brought from the east, a ritual technique known as liao 燎 was common in the Shang oracle bone inscriptions (OBI) and, judging from the form of its character, probably involved burning.Footnote 136 Initially, it was offered to a wide range of natural entities and ancestral spirits, but it underwent phases of greater or lesser popularity, and its range of targets eventually decreased.Footnote 137 The Zhou acquired the custom of liao and probably performed it in the pre-conquest period, judging from its appearance in the Zhouyuan oracle bones. Their stipulated targets for the rite were limited to an entity which may or may not be the River (He 河), as well as the Marshals (Shishi 師氏), real figures known from bronze inscriptions. The involvement of the latter suggests that the rite was already developing an association with military affairs by the time the Zhouyuan bones were produced.Footnote 138

The AS database inscriptions contain only one instance of the character liao 燎, plus a second case, written 尞, that was probably meant to indicate the same thing. Both refer to ceremonies held in the wake of successful military campaigns.Footnote 139 In the inscription of the Xiao Yu ding, as part of a great victory celebration at the Zhou Temple (Zhoumiao 周廟), Yu formally presents ears severed from his foes. This is accompanied by a liao-offering:

王乎(呼) … 令 … 氒(厥)![]() (聝)入門,獻西旅,

(聝)入門,獻西旅, ![]() (以) … 入燎周廟,盂 … 入三門,即立中廷,北鄉(嚮),盂告。

(以) … 入燎周廟,盂 … 入三門,即立中廷,北鄉(嚮),盂告。

The king called on … to order … their ears in through the gate and present them in the western part of the facility taking [the ears] and submitting [them as] a liao-offering at the Zhou Temple. Yu … entered the three gates and took up position in the center of the hall facing north; Yu reported.Footnote 140

The poor condition of the inscription makes it hard to determine who conducted the liao in question. Provided that the term ling 令, “to order, to command,” is read as a verb, however, it is unlikely that the king carried it out himself. Perhaps Yu, as leader of the successful military campaign, enjoyed the honor of performing a liao-offering in the king’s presence. Here, the liao was only one part of an extended ritual event that brought together military officials, local potentates, and the king for drinking, libations, a dress parade, reporting of a successful campaign, invocations, divinations, offerings to the royal ancestors, and rewards.

The Yongbo X gui (4169) (Figures 1.11 and 1.12), on which the second occurrence appears, was reportedly found near Xi’an, Shaanxi, in the Zhou heartland.Footnote 141 Though the AS database dates it to the early Western Zhou, the shape and decoration of the vessel suggest a dating no earlier than the reign of King Zhao, and potentially that of King Mu.Footnote 142 The inscription commemorates a reward received by Yongbo X – based on his name, the head of a lineage called Yong – after the king’s return from a campaign against two troublesome populations:

隹(唯)王伐逨魚, ![]() 伐𣶃黑,至尞于宗周,易(賜)

伐𣶃黑,至尞于宗周,易(賜)![]() (庸)白(伯)

(庸)白(伯)![]() 貝十朋,敢對揚王休,用乍(作)𦨶(朕)文考寶

貝十朋,敢對揚王休,用乍(作)𦨶(朕)文考寶![]()

![]() ,其萬年子子孫孫其永寶用。

,其萬年子子孫孫其永寶用。

When the king attacked the Laiyu, came out, and attacked Zhuo?hei, [he] delivered a liao-offering at Zongzhou. [The king] presented Yongbo X with ten strings of cowries. [I, Yongbo X,] praise the king’s beneficence in response, thereby making a precious offering tureen (gui) for my deceased father. May [my] descendants eternally treasure and use it for ten thousand years.

The king led the campaign mentioned in the inscription personally, and it seems that he conducted the subsequent liao-offering as well. The inscription unfortunately does not provide grounds to tell how Yongbo was involved. Yongbo may have participated in the campaign with the king, assisted the king in performing the liao rite, or simply been present.Footnote 143 Whatever the logic behind his reward, however, he evidently received it along with the king’s liao rite.

Liao in the “Shi fu”

The Xiao Yu ding account describes a triumph in miniature, held under the watchful eye of the Zhou king. It contrasts intriguingly with a liao mentioned in the “Shi fu” chapter of the Yizhoushu, connected with King Wu’s victorious return to the Zhou homeland.Footnote 144 The latter account shares most of the previously mentioned elements, but its overall sequence is quite different; the king and his adherents conduct a formalized progress from outside the city walls to the Zhou temple, with offerings at each stage. The victory ceremonies described in the “Shi fu,” in fact, resemble remarkably the traditional model of the Roman triumph. The king’s ceremonial arrival, apparently distinct from his actual arrival, and the parading of the remaining captives through the city adorned in finery, progressing to the temple, have analogues in Roman examples.Footnote 145

The freedom of movement shown in the “Shi fu” account, I suspect, derives from the king’s personal performance of the rite and, by extension, his personal enjoyment of the benefits. Yu’s triumphal ceremonies took place in a fixed location under the close control of the king and royal representatives. The royal house seems to have understood the danger inherent in allowing Yu to perform liao and to have taken pains to integrate that performance into a framework dominated by the king’s hospitality activities and ancestral offerings. This framing helped maintain the royal house as an “obligatory passage point” for prestige and recognition in the wake of a major military victory, which, though auspicious, could potentially destabilize the budding Zhou hierarchy.Footnote 146

The  Offering

Offering

In the bronze inscriptions, the term ![]() is rare compared to such terms as di and hui. It is central to the short inscriptions of the Wu Yin Zuo Fu Ding fangding 戊寅作父丁方鼎 (2594) and the Fu Yi zun 父乙尊, two bronzes of likely Shang date.Footnote 147 In three Western Zhou inscriptions, it appears in conjunction with other rites.Footnote 148 The Shu Ze fangding inscription connects it with an entreaty (hui) that the Zhou king (probably King Cheng) conducts at Chengzhou prior to an audience with his retainers. The Mai fangzun 麦方尊 (6015) describes the visit of a regional lord to the center of Zhou power at Zongzhou, where an early Western Zhou king (probably King Kang) assigns him a new state.Footnote 149 Afterward, this new Lord of Xing travels to nearby Pangjing, where the king conducts an event that includes feasting, ancestral devotions, and gifts. Here,

is rare compared to such terms as di and hui. It is central to the short inscriptions of the Wu Yin Zuo Fu Ding fangding 戊寅作父丁方鼎 (2594) and the Fu Yi zun 父乙尊, two bronzes of likely Shang date.Footnote 147 In three Western Zhou inscriptions, it appears in conjunction with other rites.Footnote 148 The Shu Ze fangding inscription connects it with an entreaty (hui) that the Zhou king (probably King Cheng) conducts at Chengzhou prior to an audience with his retainers. The Mai fangzun 麦方尊 (6015) describes the visit of a regional lord to the center of Zhou power at Zongzhou, where an early Western Zhou king (probably King Kang) assigns him a new state.Footnote 149 Afterward, this new Lord of Xing travels to nearby Pangjing, where the king conducts an event that includes feasting, ancestral devotions, and gifts. Here, ![]() is part of the ritual program, occurring together with a feast near the beginning of the ritual sequence.

is part of the ritual program, occurring together with a feast near the beginning of the ritual sequence.

Both the Mai fangzun and the Shu Ze fangding are early Western Zhou vessels; they commemorate ritual events that kings conducted while establishing the political infrastructure of the Zhou state. The Fan you, in contrast, is a middle-Western-Zhou vessel commissioned by a subordinate (and likely kinsman) of a figure there called gong 公:

隹(唯)九月初吉癸丑,公![]() 祀,𩁹旬又一日辛亥,公啻(禘)

祀,𩁹旬又一日辛亥,公啻(禘)![]() 辛公祀,卒事亡

辛公祀,卒事亡![]() …

…

It was the ninth month, the chuji moon phase, the guichou day. The Duke performed ![]() -offerings. Eleven days later, on the xinhai day, the Duke performed a di/chi offering and a

-offerings. Eleven days later, on the xinhai day, the Duke performed a di/chi offering and a ![]() -offering to Duke Xin. The business was completed without harm.…

-offering to Duke Xin. The business was completed without harm.…

The Fan you inscription unambiguously describes two separate instances of ![]() , separated by a significant time gap.Footnote 150 No additional rite term is given for the first instance, as in the Shu Ze fangding inscription. Like the person conducting the rite, the target of the second

, separated by a significant time gap.Footnote 150 No additional rite term is given for the first instance, as in the Shu Ze fangding inscription. Like the person conducting the rite, the target of the second ![]() offering, at least, carried the title gong 公. We can reasonably assume that Duke Xin was a forebear of the contemporary Duke and that the

offering, at least, carried the title gong 公. We can reasonably assume that Duke Xin was a forebear of the contemporary Duke and that the ![]() rites in question should be understood as ancestral offerings.

rites in question should be understood as ancestral offerings.

As recorded in the Western Zhou inscriptions, ![]() occurred only together with other ritual techniques and only in contexts where political activities were conducted. Apparently,

occurred only together with other ritual techniques and only in contexts where political activities were conducted. Apparently, ![]() was not a personal rite, as hui and yu sometimes were; it appears only in cases in which multiple attendees are mentioned by name or title. The two early instances were part of major events at which the king sought to legitimize his authority in a ritual context and strengthen bonds between the royal house and the uppermost echelon of Zhou adherents.Footnote 151 The Fan you inscription, from the middle Western Zhou, records no associated inter-lineage political activities. It does, however, explicitly record that the performance of the

was not a personal rite, as hui and yu sometimes were; it appears only in cases in which multiple attendees are mentioned by name or title. The two early instances were part of major events at which the king sought to legitimize his authority in a ritual context and strengthen bonds between the royal house and the uppermost echelon of Zhou adherents.Footnote 151 The Fan you inscription, from the middle Western Zhou, records no associated inter-lineage political activities. It does, however, explicitly record that the performance of the ![]() and di rites created an opportunity for the Duke (gong 公) to reward a subordinate.

and di rites created an opportunity for the Duke (gong 公) to reward a subordinate.

The Fan you inscription contains the latest appearances of ![]() , not just in the bronze inscriptions, but in any source. It has been suggested that

, not just in the bronze inscriptions, but in any source. It has been suggested that ![]() was equivalent to rong 肜 and that both that term and the related yi 繹 served a similar purpose in later texts.Footnote 152 The case for this theory is weak, and the use of

was equivalent to rong 肜 and that both that term and the related yi 繹 served a similar purpose in later texts.Footnote 152 The case for this theory is weak, and the use of ![]() in the Western Zhou inscriptions does not support its identification as a “next-day” rite; rong 肜 is more likely a separate concept.

in the Western Zhou inscriptions does not support its identification as a “next-day” rite; rong 肜 is more likely a separate concept. ![]() , it would seem, did not become part of the overall shared milieu of Zhou ritual. Its association with major, multiday events likely contributed to its decline, as the royal house and other powerful elites shifted to different strategies of ritual legitimation.

, it would seem, did not become part of the overall shared milieu of Zhou ritual. Its association with major, multiday events likely contributed to its decline, as the royal house and other powerful elites shifted to different strategies of ritual legitimation.

Yu 禦 (Exorcism/Warding)

The bronze inscriptions contain a few examples of the term yu 禦, used by both the Shang and the Zhou to denote a negative entreaty – a plea to the spirits to prevent or repair some uncomfortable situation.Footnote 153 Chronologically, the occurrences of yu in the bronze inscriptions group neatly into two clusters: a few dating to the late Shang or early Western Zhou, all the work of nonroyal elites; and two appearing in the unusual late Western Zhou inscriptions associated with King Li.

Nonroyal Instances of Yu 禦 (Early Western Zhou)