Book contents

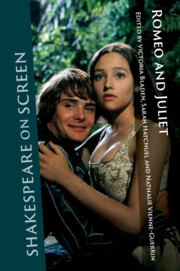

- Shakespeare on Screen: Romeo and Juliet

- Series page

- Shakespeare on Screen: Romeo and Juliet

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Introduction – From Canon to Queer: Romeo and Juliet on Screen

- Part I Revisiting the Canon

- Part II Extending Genre

- Part III Serial and Queer Romeo and Juliets

- Index

- References

Part II - Extending Genre

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 October 2023

- Shakespeare on Screen: Romeo and Juliet

- Series page

- Shakespeare on Screen: Romeo and Juliet

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Introduction – From Canon to Queer: Romeo and Juliet on Screen

- Part I Revisiting the Canon

- Part II Extending Genre

- Part III Serial and Queer Romeo and Juliets

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Shakespeare on Screen: Romeo and Juliet , pp. 93 - 168Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023