The Berlin Wall and its impact on personnel at the Berliner Ensemble

With hindsight, it might seem that the GDR authorities had telegraphed the building of the Berlin Wall to the cultural sector. In the field of the performing arts, the Ministry of Culture surveyed theatres, opera houses and other institutions for the number of staff who were living in West Berlin in May 1961, three months before construction started on 13 August.1 According to the responses, the Berliner Ensemble submitted its twenty-seven names sometime in June. Today it is clear that the Ministry was pre-emptively assessing the impact that the closure of the border would have on the GDR's ability to keep its venues open. Yet it is difficult to ascertain who knew the ends to which the information was to be used. Kurt Bork was aware that something significant was afoot because the document to which I have referred notes concern about how the Staatsoper and the Komische Oper were to play on, considering the large numbers of West-dwelling staff at those institutions. However, such surveys were not unusual in themselves. For example, the Ministry had asked the BE for details of its West Berlin members ahead of its tour to Halle in 1959.2 The theatres and opera houses probably thought that this was just another bureaucratic hoop through which they were required to jump. What the survey did not identify was the potential for additional East German staff either to defect or to remain in the West because they were already working there as guests. This was the case for Peter Palitzsch and Carl Weber, who were directing Brecht plays in Ulm and Lübeck, respectively. It would seem from the evidence that the authorities and the BE were not that concerned about Weber's decision; instead they focused on the loss Palitzsch represented practically as a director and symbolically as a Brecht Schüler.

Initially, Manfred Wekwerth proceeded as if the Wall had had no impact on Palitzsch and his work at the BE. In a letter written barely two weeks after the border was closed, Wekwerth told Palitzsch that they needed to sort out the Fabel for the next major BE project, Brecht's Coriolan. He also noted that the BE would not be publicly protesting against the rumoured Brecht boycott in the FRG: ‘after all, why should we be surprised that, in a revolutionary situation, counterrevolutionaries behave in a counterrevolutionary manner?’3 Wekwerth's blasé tone may surprise us today, but for many committed socialists, the Wall was not in itself a bad thing. Hilmar Thate, who would leave the GDR to work in the West in the wake of the Biermann affair of 1976 (see pp. 295–6, Chapter 9), believed that the Wall would actually allow greater freedom and democracy in the GDR because the state could now proceed with its own business without the pressure exerted by an open border.4 Such illusions were sometimes slow to fade. The banning, straight after its premiere on 30 September 1961, of Heiner Müller's Die Umsiedlerin (The Resettler), for its critical stance on elements of GDR society, did little to puncture optimism: the BE's ‘Parteileitung’ (‘local party leadership’) sent a letter denouncing the play and its production to the Ministry.5

By early September, the BE still hoped to convince Palitzsch to return. A memorandum of a meeting with Minister Hans Bentzien records that the GDR press should be instructed to refrain from making any mention of Palitzsch, lest it prevent him from reconsidering his position.6 A plan was hatched to have Wekwerth meet his directing partner in Austria or Scandinavia, that is, not on German soil.7 Wekwerth had initially turned his back on Palitzsch ‘definitively’, but he then sought to convince him to return ‘with his very best efforts’.8 (This information is to be found in Wekwerth's Stasi file, and I will return to the Stasi's connection with the BE in the following chapter. Here it is worth noting that Stasi intervention may have changed Wekwerth's attitude towards his colleague in the interests of the BE and the GDR. Yet by November, Wekwerth was referring to Palitzsch's decision as treachery.)9

Palitzsch was in no mood to compromise and rejected an offer to meet in Oslo by arguing that the Wall was not a measure designed to combat the West, but the GDR's own workers.10 The BE's response to his final decision was a vitriolic open letter, published in Neues Deutschland, that reproached him for leaving the country in which the ‘[Arturo] Uis’ had been politically and economically disempowered and concluded in trenchant style: ‘we have suffered losses. We have made up for them’.11 The BE had not, however, made up for the loss. Despite the GDR press blackout and the BE's continued efforts, the West German Tagesspiegel reported that Palitzsch was not going to return to the GDR. The BE tried to get Kurt Palm, the head of the costume department at the GDR's State Workshops, to replace Palitzsch,12 but he did not want to return to the GDR either. And while the authorities insisted that actors living in West Berlin either move to the GDR or have their contracts cancelled, a ‘special arrangement set up by the Ministry’13 allowed Erich Engel to remain in the West while directing at the BE. Exceptions were made where necessary, it seems.

Head of Administration at the BE, Hans Giersch, painted a picture of the effects of the Wall on the BE's personnel in November. While he acknowledged that he had not yet discussed contracts with all West Berliners, he could establish that the company had lost nineteen staff, including four instances of ‘Republikflucht’ (‘flight from the Republic’), which included Palitzsch14 and Weber, and two actors. Eight West Berliners decided to stay at the BE. The company was planning to employ four new actors in the 1962/63 season, including Gisela May, who went on to enjoy an international reputation as a chanteuse singing Brecht's songs, and Renate Richter, who would marry Wekwerth and become one the BE's leading actors later that decade and again when her husband was appointed Intendant in 1977.15 Despite the relatively modest damage done in terms of lost ensemble members, the repertoire was nonetheless in trouble: the company needed to rehearse new actors to replace those who stayed in the West, and deal with bouts of illness. However, the BE took pains to avoid the Western media attributing the disruption to the Wall, something that could be ‘interpreted maliciously’.16

The events of 13 August 1961 did have a negative effect on the BE's ability to realize its plans. The triumvirate of young directors who looked like they would lead the company after 1956 was no more, and Manfred Wekwerth was without a directing partner. The East German audience had to wait over a year for the BE's next major production; the audience in the West had to wait considerably longer.

The Wall and the problem of touring

One of the BE's great attractions to the SED was that the company was regularly invited to tour politically important countries, including those in which the GDR was not diplomatically recognized. The many countries making invitations wanted to see innovative and high-quality theatre, something that made the BE the GDR's most prestigious cultural export. The construction of the Wall had a direct effect on the BE's ability to tour the West, and the problems lasted for years, rather than months. With the exception of a one-night performance of the first Brecht-Abend (see below) in Helsinki in 1962, the BE did not travel beyond the Warsaw Pact countries again until 1965, when it returned to London to be welcomed back like the prodigal son. The effects of the Wall were felt almost immediately. In what looks like a text for a press release, the BE noted that its performances at the Venice Biennale scheduled for September 1961 had been cancelled. The Italian authorities had withdrawn entry visas at the last minute ‘to our great astonishment’.17 Weigel received personal apologies from the Biennale's head, who asked whether a postponement, rather than a cancellation would be possible.18 The BE did not return to Venice until 1966.

The BE, and indeed any GDR theatre, had to negotiate two hurdles in order to tour non-communist Europe: the West Berlin ‘Travel Board’, the gateway to the West administered by the three remaining allies, and the host country's own immigration departments. The BE failed to clear both of these for a planned tour of Denmark in 1963. Danish coalition politics played its part here: the Minister of Justice reportedly turned down the visa application in September although the Prime Minister was said to have supported the tour.19 In any case, the Travel Board refused visas at the West German end.20

The story of the BE's prolonged absence from the UK in the early 1960s shows how pressure came both from within and without the British government. James Smith, whose assiduous work on the subject looks back to how the UK authorities sought to frustrate the tour of 1956 as well, writes that the Foreign Secretary blocked the issue of travel visas to the BE for a trip to the Edinburgh Festival without the Prime Minister's knowledge. The news of the refusal began to leak around the time of the Profumo affair in 1963, and the government found itself overwhelmed by ‘a wave of negative publicity’.21 Prime Minister Harold Macmillan felt that decisions that should have been taken by the UK were instead being ‘bullied’ out of them by the FRG.22 Against the backdrop of this pressure, the National Theatre invited the BE to London in January 1964. Kenneth Tynan, who was the literary manager at the National Theatre, reported that Laurence Olivier was delighted at the prospect of a tour in August.23 By this time, the issue of visas for GDR artists had become so contentious that it was debated in the House of Commons on 3 and 25 February 1964,24 and the government decided to relax travel regulations in March.25 However, this plan to tour the West was also scuppered by the Travel Board.26

An interesting footnote to the proposed 1964 tour of London concerns the role of the SED in the business of another Warsaw Pact country's cultural affairs. Tynan had warned Weigel that a Polish troupe would be bringing a production of Arturo Ui to London in May. This plan was in fact already known to the Ministry of Culture; Kurt Bork feared that a Polish Ui would make the need for a home-grown GDR production superfluous and thus undermine the GDR's struggle against travel restrictions.27 Weigel was also aware of the tour and wrote to the Viennese-born director of the Polish Ui, Erwin Axer, someone whom she and Brecht had met on a trip to Poland in 1952.28 She noted both that he had not sought permission to take the production to London and, more importantly, that it was tactical for London to develop a hunger for Brecht which only the BE could satisfy. This blatant statement of self-interest was concluded with a plea for Axer's solidarity with the GDR.29 The director replied that he had applied for the rights and that he considered he was very much acting in Brecht's interests.30 In addition, GDR Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs, Herbert Krolikowski, reported that the Polish Foreign Minister was also in favour of the tour.31 Yet despite the Polish support, Bork told Weigel later that year that it was the Ministry of Culture's intervention that prevented the tour.32 Axer's response was never to direct Brecht again.

The incident shows that the BE could align its position with that of the GDR authorities when it served its interest, how resolute the GDR authorities were in fighting the travel ban, and how far they were prepared to go in negotiations to secure the primacy of the BE as a GDR theatre company. It is hard to overlook the irony that the same party that imposed widespread travel restrictions on almost all its populace expended so much time and energy to ensure the travel privileges of a single theatre company. Ultimately, the SED got its way, and the BE was much fêted when the boycott was finally lifted and it returned to London in 1965.

The Brecht-Abende and other shorter productions

In response to its own low productivity and the attendant problems this created, the BE hit upon a format that could enliven the fatigued ensemble and the samey repertoire. It began to work on pieces with shorter rehearsal periods and less orthodox Brechtian material that did not demand the deference accorded to the ‘great’ plays.

The Brecht-Abende (Brecht Evenings) actually emerged from a practical necessity. A performance of Galileo had to be cancelled at very short notice, and the BE was not able to inform theatre-goers in good time. Ernst Busch together with other actors sang or recited their favourite songs and poems by Brecht, and, according to Wekwerth: ‘the success was astounding’.33 The impromptu event led to the compilation of the first Brecht-Abend, simply subtitled ‘Lieder und Gedichte 1914–1956’ (‘Song and Poems 1914–1956’). It had its first performance on 26 April 1962. The evening included roughly forty items, with the programme nonetheless indicating a degree of flexibility in the note ‘subject to change’. The choice of material was certainly partisan, although it was not exclusively composed of rousingly militant pieces. Indeed, a selection from the Buckower Elegien (Buckow Elegies), the poems written in the wake of 17 June 1953, was included, although the performers did not recite the ones famously critical of the SED, like ‘Der Radwechsel’ or ‘Die Lösung’ (‘Changing the Wheel’ or ‘The Solution’). The GDR press, which seems to have been the main body covering the show, was uniformly enthusiastic. One reviewer observed the relaxed atmosphere that accompanied the evening and regretted that the performance had to take place on stage, preferring closer communion with the actors.34 Another reported the twenty-minute applause that followed the Abend.35 The review in Neues Deutschland was also very favourable and noted that the programme indicated that this was just ‘Brecht-Abend Nr. 1’.36

The GDR audience certainly had to wait for the next instalment, which built on the success of the format and the positive responses to it by expanding both the scope and ambition of the second Evening. There was no formal plan for how the BE was going to follow up its initial success; the company merely believed it was an idea worth developing. Young directors Manfred Karge and Matthias Langhoff, one of Wolfgang Langhoff's sons, set the second Evening in motion when they asked Weigel whether they could work with actors who were not involved in Erich Engel's production of Brecht's major play Schweyk im Zweiten Weltkrieg (Schweyk in the Second World War). The new Evening, entitled ‘Über die großen Städte’ (‘On the Great Cities’), came in two halves. The first echoed the previous Brecht Evening in that it consisted of recitations and songs, here related to the Evening's theme. The second half presented a novelty, the reconstitution of Brecht's Das kleine Mahagonny (The Little Mahagonny), that is, the Songspiel version of Brecht and Kurt Weill's opera Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny). This is a stripped-down version which only includes songs and linking texts written by Brecht, rather than dialogue. Weill scholar David Drew had already unearthed the six songs and four intermezzos that form its musical heart. The problem with the plan was that there was no extant script for the linking texts, something Karge and Langhoff discovered upon visiting the Brecht Archive. They thus decided to write their own in a ‘Brechtian’ style, based on the reminiscences of Weigel and Elizabeth Hauptmann, who saw the original production in 1927. The directors cheekily went back to Weigel claiming that they had discovered the texts themselves. Weigel reportedly said they looked familiar.37

The evening premiered on what would have been Brecht's 65th birthday, 10 February 1962, a day that opened with the ceremonial renaming of the area in front of the BE as ‘Bertolt-Brecht-Platz’.38 This evening, like the first, was warmly received, and reviewers were again impressed by the relaxed manner in which it was conducted.39 The only dissenting voice was Rainer Kerndl at Neues Deutschland.40 Karge and Langhoff paraphrased his critique at a party meeting in the BE on 15 February as ‘formalist ideas and their realization’.41 The indignation did not end in the BE. Former Minister Alexander Abusch publicly criticized Kerndl in Neues Deutschland and asserted that the show ‘turns content and form into an inextricable dialectical unity’.42 Such a high-ranking intervention suggests the hand of Weigel, who had good connections with the upper echelons of the SED. On the other hand, the counter-comment may have come directly from the SED, as it, after all, was basking in the reflected glory of the celebration around Brecht's anniversary, too.

Both Evenings were popular and were performed over fifty times in runs of roughly four years. The third Evening was the most ambitious yet, and also, as will become evident, the BE's most personal. Werner Hecht, who was editing a new collection of Brecht's theoretical writings, suggested performing the Messingkauf. As John J. White puts it:

the nature of this grandiose project and Brecht's failure to complete it go hand in hand…Der Messingkauf attempts to expound, illustrate and perform theory by means of an ingenious presentational strategy largely dictated by the theatrical medium that is at the same time the work's subject matter.43

Hecht had his work cut out: Brecht took up and went back to the Messingkauf project at various times from 1939 to 1955, and the many fragments fill over 170 pages in the standard edition.44 The project did not merely stop with the production of a workable and playable script, however. The BE included three ‘demonstrations’ of practice, taken from its own repertoire, and five exercises for actors, three that appear in the Messingkauf itself and two devised by the BE.45 This was a complex and ambitious project, which was also, in part, a response to audience demand as recorded in earlier post-show discussions.46

The decision was taken to stage the project in September 1963 in the belief that it would have a very short run.47 The BE was of the opinion that this would be a show for a more specialist audience, and Weigel wanted Wekwerth and his team of young directors to present it on the Probebühne (‘rehearsal stage’), which had a capacity of 100. Wekwerth, however, rehearsed on the main stage behind Weigel's back and provoked her ire when she found out. She was only placated by the positive reviews.48 It turned out that she would have much of which to be proud. The show ran for 100 performances between its premiere on 12 October 1963 and its last night on 17 June 1970. Over this time, the script was continually reviewed and revised, and the project represented the BE's attempt to communicate its own ‘secrets’ by performing theory to enthusiastic audiences.

The engagement with the fragment and its development over time betokened the special relationship between the BE and Brecht's performance philosophies. Kenneth Tynan had asked whether an English-language Messingkauf would be performable. Elisabeth Hauptmann argued against the plan, writing that the show could not be easily transferred because it was the result of the BE's own experiences.49 This sentiment was echoed shortly after the Messingkauf left the repertoire. The great director of Brecht's plays in the West, Harry Buckwitz, asked whether he could use the BE's version in Zurich and received a similar reply to Tynan from Joachim Tenschert.50 The BE was convinced that the Evening was a product of its own unique response to experiences garnered from years of hard work.

The BE's audience had to wait over four years for the next Brecht Evening. Karge and Langhoff directed another fragment, Der Brotladen (The Bread Shop), a world premiere that opened on 13 April 1967 and enjoyed similar success and a similar run to that of the Messingkauf. The fifth and final Evening was conversely a very damp squib and reflects the malaise at the company in the late 1960s. Designed to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the GDR, Das Manifest (The Manifesto) featured Brecht's versification of Marx's Communist Manifesto together with a selection of poems, prose, songs and scenes. It premiered on 1 October 1969 and ran for the next four days playing evening and afternoon slots. Critics were mainly underwhelmed; one wrote that the show lacked ‘dynamism, passion, originality’.51 It was perhaps this lacklustre treatment of a tired format that led to its demise.

However, before moving on from this more compact and flexible form, I will linger briefly on a variation developed in the mid 1960s, which was intended to be the first of a series, but which was not to be continued. The first ‘Nachtschicht’ (‘Night Shift’) was named after a popular song of the early post-war years, ‘Also wissen Se nee’ (‘Don'tcha know’) by Bully Buhlan, and this period provided the backdrop for a loose collection of songs and sketches. The emphasis was on entertainment, and a compère linked the different items. There was a definite lightness to the evening, and the compère stressed that the audience was in for a Brecht-free evening. He humorously offered spectators their money back if they detected a Verfremdung or a free ticket for anyone who uncovered a Gestus.52 The evening was the brainchild of Peter Sodann, who would become a successful Intendant himself in the GDR of the 1980s. At the time, however, Weigel had taken him under her wing; he had been arrested and imprisoned for nine months for his part in a satirical cabaret group in 1961. He began rehearsals, but Wekwerth took them over, as Sodann reports: ‘they feared the worst; at the end of the day, the BE wasn't a bourgeois pleasure palace’.53 Indeed, the positive reviews from East and West still noted a didactic tone amongst the jollity: ‘forgetting [the privations of the post-war period] with a smile, so as not to forget – that was the evening's dialectic. We were in the BE after all’.54

Coming out with guns blazing: Die Tage der Kommune as a defence of the Wall

The first Brecht Evening was not only a useful gambit to help expand and enhance the BE's repertoire, it also represented the first new piece of work after the erection of the Wall. Its commitment to Brecht and his politics was a rousing, but not uncritical statement of solidarity with the state in which he had chosen to settle. In this sense, the Evening echoed Brecht's full letter to Ulbricht on 17 June 1953. Yet the BE could not survive on new evenings of songs and poems alone, however well performed and well received they were. The company's first major post-Wall production was to present a resolute front and necessitated a change of production plan. Wekwerth's letter to Palitzsch of late August 1961, quoted above, noted that the BE was busy preparing Brecht's unfinished Coriolan. By November planning had begun on Die Tage der Kommune (The Days of the Commune), the play about which the SED had had grave doubts in 1951. Wekwerth and Besson had co-directed the play in Karl-Marx-Stadt in 1956, although it had not been terribly successful. By 1958 at the latest, the SED considered the play fully rehabilitated and suggested it, together with Saint Joan of the Stockyards, as a replacement for The Threepenny Opera and Man Equals Man in the BE's proposed production plan.55 The decision to switch from Coriolan to Commune did not receive any objections in 1961.

Wekwerth's experience of Karl-Marx-Stadt led him to the conclusion that the BE would have to adapt Brecht's text because he believed that he and Besson had not worked on a bad production, but on a bad play.56 One of the major additions to the Berlin production was the inclusion of documentary material taken from the protocols of the Paris Commune itself. Here the Fabel was not to change; the additional text was there to bolster it. Manfred Karge reported Wekwerth's basis for the production: ‘we can't think we know better. We shouldn't talk of the characters’ mistakes, nor overly emphasize them; our criticism must be objective: these are mistakes made in a non-revolutionary situation’.57 The production's Fabel becomes clear if one analyses the quotation's final point first: all the action takes place ‘in a non-revolutionary situation’, a time at which history was not ‘ripe’ for revolution, in Marxist parlance. In other words, the material situation of the Communards drove them to insurrection, but the absence of an organized communist party meant that they were doomed to failure: history was not ready for a popular revolution in 1871. Consequently, their actions, unbeknownst to them, could never succeed, yet, as the quotation shows, it was their valiant efforts, rather than their political naïvety that was to be the focus of the production.

Wekwerth, who thrived in directing partnerships, teamed up with head dramaturge Joachim Tenschert, and they proceeded to work on the performance implications of the Fabel. These were evident to critic Dieter Kranz: the directors ‘had managed to pull off a remarkable feat by combining a demonstrative didactic acting style with the methods of Stanislavsky’.58 Such a combination may remind the reader of Brecht's 1951 production of The Mother in its careful manipulation of audience sympathies. The production of Commune strategically deployed empathy to attach the spectators to the flawed revolutionaries in order to guide them away from undue criticism and towards admiration for the Communards. As Laura Bradley notes: ‘Wekwerth sought to win his spectators’ sympathy for the Communards in Brecht's play, on the assumption that if the spectators wanted the Commune to continue, they would accept the means necessary to achieve that end’.59 The critical aspect retained by the production invited the audience to understand the reasons why the uprising failed.

Rehearsal was due to start on 1 January 1962 for a premiere in mid March.60 After a not inconsiderable 212 rehearsals, the production finally went up on 7 October 1962. The BE was not concerned with delivering its response to the Wall that quickly; instead, as had become the ‘tradition’ over the years, it strove to craft a production that would endure and reward the exertion of the creative team and the actors. Commune ran for almost nine years. The production certainly had a Brechtian edge in that it emphasized action, deeds and contradictory situations over local colour. What almost every review noted was the production's relationship to very recent history. GDR critics viewed the show as a defence of the ‘the protective measures of 13 August 1961’ and understood that the Communards failed due to ‘indecision and naïvety’ – they used force too late (unlike, by extension, the GDR).61 Another East German reviewer noted the optimistic thrust: the Paris Commune as ‘the first battle on the way to victory’.62 The ultimate seal of approval was delivered by no less a politician than Walter Ulbricht who enthused about the production to Weigel.63

A Western reviewer, on the other hand, pointed to the way in which the aesthetics helped to carry the production's pro-Wall stance: ‘you are transported by the perfection, by the sober brilliance of the production; you are concerned about the amount of agitation that this brilliance supports’.64 Again one observes the ways in which well-rehearsed artistic perfection was used not to open up a dialectic but, on the contrary, to narrow it and make it serve political ends. However, it was not only the East that had a propagandist agenda. Many Western papers were quick to point out that Wolfgang Langhoff had started playing the role of Langevin in Commune almost a year after the premiere. The SED had stripped Langhoff of the DT Intendanz earlier in 1963 after it banned Peter Hacks’ play Die Sorgen und die Macht (Worries and Power). The title of one article indicates the general thrust of the inter-German sniping: ‘Intendant Langhoff Now Simple Actor’.65

Shakespeare at the Berliner Ensemble: Coriolan as an unqualified success?

After the premieres of Commune and Schweyk in the Second World War in the autumn of 1962, the BE's audience had to wait almost two years for the next major production, Coriolan. Indeed, the wait for this particular play was a considerable one; Brecht began adapting Shakespeare's Coriolanus in 1951, but a combination of official disapprobation in the same year66 and a dearth of suitable actors to play the title role led him indefinitely to postpone the project.67 By the 1960s both problems had been resolved. The Ministry actually praised the plan to stage Coriolan68 as an engagement with the Erbe69 and the BE had a viable Coriolan in the star of Ui, Ekkehard Schall. What the company lacked was a viable text.

Wekwerth was not satisfied with Brecht's unfinished adaptation and felt that the BE could improve on what he considered to be some of Brecht's false emphases. I do not wish to examine the adaptation process here and will instead point out some of the problems that the adaptation wanted to address. Wekwerth, who had seen the unsuccessful world premiere of Brecht's adaptation in Frankfurt am Main in 1962, noted a ‘tendency to idealize the people that should counterbalance Shakespeare's idealization of the nobility’.70 The BE did not want to show the people as ‘Revoluzzer’ (an untranslatable German term, usually used disparagingly towards revolutionaries who do not have the wherewithal to conduct a revolution), nor as Brecht's own ‘revolutionaries’, but a group that had ‘a revolutionary Haltung’.71 The representatives of the common people were thus to show that they could develop productive political behaviour, but that this was neither given nor inevitable.

Coriolan himself presented a great problem, primarily due to the perceived status of protagonists in general in the works of Shakespeare. Matthias Langhoff identified an unchangeability in the character that ‘demands a mode of acting unknown to our theatre’.72 The point of view persisted into rehearsals where an anonymous Notat-taker wrote that Coriolan ‘is of a fixity that pervades his diction and his gestures, he's become a montage of this fixity, constructed from naïve and contradictory behaviour’.73 Thus the BE's solution was to present the unchangeable figure in all possible contradictory richness, although this is a peculiar point to have reached in the first place for a company with the BE's intellectual heritage. Nancy C. Michael writes: ‘neither Shakespeare's Coriolanus nor Brecht's Coriolan has a place in society, Coriolanus because he will not condescend, Coriolan because he will not adapt’.74 This position, not an uncommon one in Western Brecht criticism, imputes to Coriolan an intransigence that borders on existentialism, in which human subjects have complete freedom of choice over all their decisions. In this reading, Coriolan has the power to choose whether he changes or not, something that contradicts the very nature of the dialectical process. The dialectic does not work exclusively on the conscious mind, and adaptability in human beings is a prerequisite for dialectical movement: its advance cannot simply be held up because a particular character chooses not to be subject to a mechanism that is historically irresistible. It is not, then, that Coriolan is unable to adapt; he, by definition, adapts to every change of circumstance that runs through the play. His problem is that he continually makes the wrong choices in a society that indulges his individualism. In this understanding of the dialectic, individualism is the tragic component of the play, in that the hero only views it positively, while society takes a far more pragmatic approach to it. That the BE chose to follow an undialectical reading of Coriolan's character is surprising, and its decision merely to offer a contradictory kaleidoscope is ahistorical at best.

One attempt to contextualize the Roman Coriolan was to re-emphasize the rivalry with Aufidius, the leader of the Volscians. Wekwerth believed that this helped to undermine Coriolan as a singular hero by framing his need for victories socially.75 The victories were not in some way abstract, but concrete means of achieving greatness in Rome over a named opponent. After all, the character gains the honorary title ‘Coriolan’ from his defeat of Aufidius at the Battle of Corioli, and this offered the production another opportunity to engage in materialist analysis.

Brecht had not rewritten the battle scenes, preferring to consider them on stage, in rehearsals that were never to take place. Wekwerth and Tenschert observed that some productions did not stage the battle scenes in the belief that one should simply take Coriolan's martial mastery in good faith. They continued that the BE did not share this view and wanted the spectator to reach that opinion having seen him ‘at work’.76 The Brechtian emphasis on exposing the ceremonial as social code allowed a dialectical view of the battle to emerge: ‘we show the savagery [of the battle] as ceremony, the chaos as order, that is only to be created by experts in warfare’.77 Action as social process helped to undermine a mythologizing reading of Coriolan in favour of one firmly rooted in his expertise.

Wekwerth and Tenschert entrusted the battle scenes to an assistant director, Ruth Berghaus. Berghaus scholarship has long considered this to be her first work at the BE, but she was in fact responsible for the crowd scenes in Commune beforehand.78 She had trained as a dancer and had been an intern at the BE between 1951 and 1953.79 She thus combined a sense of physicality with Brecht's performance principles. This is evident in a direction she gave to the actors of these scenes, who were mostly acting students gaining experience at the BE: ‘we're supposed to be showing how barbaric the fight was and how the different warriors behave differently, not how savage or barbarous our actors can be’.80 The emphasis on showing action and not characters was a priority, as was a Brechtian impulse to historicize, as Berghaus noted: ‘a battle is not taking place, on the contrary we are showing how a particular battle took place’.81 The difference between the immediacy of the former and the careful artistry of the latter denotes the care Berghaus took to stage action sequences that were not to be mistaken for a real battle, but to demonstrate its workings.

Composer Paul Dessau, Berghaus's husband and erstwhile Brecht collaborator, wrote the music for the battle scenes, which was percussive and raucous. At this time, the BE, which was always interested in making use of the latest technology in its productions, tested a stereo system to heighten the impact of Dessau's non-illustrative soundtrack.82 It should not be forgotten that in October 1963 the Beatles had recorded their first ever stereo record, ‘I want to hold your hand’, at the cutting-edge Abbey Road studios.83 The BE was only ten months behind the capitalist West. However, the price of the stereo unit from Switzerland was prohibitive and the BE's engineers suggested they build their own.

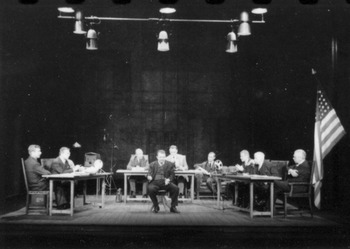

The production finally premiered on 25 September 1964. Its centrepiece was a tower, mounted on the BE's revolving stage: one side was a white stone portal, the other dark wooden gate. Much of the action played out against this central set item. The sparseness of the otherwise white cyclorama allowed the actors to set out the carefully staged Arrangements, with the battle scenes in particular unfolding as a series of tightly choreographed yet energetic set pieces (see Fig. 6.1). The physicality of the action complemented the gestic performances to lend the production a controlled muscularity that, again, allowed Schall to shine. His Coriolan articulated the pride of the character, as spectators would have expected, but the strength of the interpretation contextualized the quality squarely in the Rome of the play. The general was anchored in his society as a figure who had overplayed his hand, unable to appreciate that the majority of the people only valued him for one particular talent. The precision of the work applied to the interaction between individual and society, a hallmark of the BE, allowed audiences to view the play with fresh eyes: no longer were characters the focus as individuals, but their complex place in the antagonistic city states that populated the ancient world. The show was not only of historical interest; the clarity of the relationships also created a window onto the present, as the theme of self-assumed indispensability resonated with spectators. In a world of burgeoning individuality, what was considered a strength in the West was subjected to critique on the BE's stage.

Fig. 6.1. Exposing the general's expertise: the choreography of the battle scenes sets out Coriolan's mastery of the art of war. Coriolan, September 1964.

It is also worth noting that this production was ‘transplanted’ to the National Theatre in London in the early 1970s, where the same directing team staged the play with an English cast. One reviewer noted: ‘Wek-werth's and Tenschert's creation fits neither the text it's been given [Shakespeare's original, not Brecht's adaptation] nor the company which has been strait-jacketed into it’.84 This not uncommon response from the British press underlines just how well the direction suited the ensemble at the BE. Its traditions of gestic acting helped to dovetail a socially based interpretation with a set of performative abilities, crafted to realize it.

For the most part, the production was very well received in Berlin. Elvira Mollenschott wrote in her review for Neues Deutschland that ‘rarely…were expectations so high’:85 the BE's first Shakespeare had been a long time coming, but had not disappointed. FRG critic Urs Jenny noted a total absence of ‘a purely mechanical application of the Brechtian method’, indeed he registered his surprise at how critically Brecht's own adaptation had been treated.86 The main point of critique was the casting of a guest from the Volksbühne, Manja Behrens, as Coriolan's mother, Volumnia. Helene Weigel took over the role for the London tour because, despite her dislike for the character, she appreciated that the BE could not afford to make mistakes, especially when offering its own Shakespeare to the English.87 This was Weigel's last major new role and one for which she was much celebrated.

The immediate adulation aside, there were two more critical voices who, independently of each other, touched on similar points. In the East, Friedrich Dieckmann accused the set design, which literally revolved around the revolving tower, of running the risk of representing nothing due to its multipurpose ubiquity.88 In effect, he was referring back to the older criticism, levelled at Engel's Threepenny Opera, that (in Coriolan visual) perfection could blind spectators to an absence.89 He went on to criticize what he perceived to be a considerable shift in the BE's ethos: it had changed from being a radical workshop in the 1950s to ‘a representative institution whose fame has become something legendary across the whole of Europe’.90 Klaus Völker in the West raised the ‘accusation of artistic dogmatism and of mechanical perfectionism in the practical work’.91 He also criticized the company's lack of productivity as a disadvantage for the actors and noted that in Brecht's lifetime the productions were much debated, whereas now artistic brilliance meant that everybody seemed to like them. Völker is the first person to coin a term that would haunt the BE later that decade, that the company could become a ‘Brecht Museum’.

What the two critics describe is difficult to reconcile with the glowing reviews of the production. However, they had seen many BE productions and were in a good position to raise these reservations. My account of the realization process shows that much time and effort was spent on both the adaptation and rehearsals,92 and there is little trace of a mechanical process at all. However, the two critics both point to issues that certainly revisited the BE, and so perhaps they were able to detect failings, present at the time, that would only increase and multiply in the future. They may have taken the shine off the production, but it proved to be another great hit, given 276 times over fourteen and a half years, and toured extensively abroad. Indeed, this was perhaps the BE's final production that drew renown from around the world until Heiner Müller's Arturo Ui in the mid 1990s.

Exclusivity and orthodoxy: the Berliner Ensemble's ‘divine right’ to Brecht

Dieckmann's criticism pointed to something of a lethal process for lively theatre-making: fame had turned the BE from a radical institution into a ‘representative’ one. One can certainly discern such a shift in certain sentiments in the BE's correspondence of late 1963. Weigel had written to Wolfgang Heinz, who succeeded Langhoff as Intendant at the DT, telling him that he would be welcome to play Puntila at the BE, but not at the DT: ‘and that on principle’.93 It is worth considering why the BE felt itself uniquely charged with the task of exclusively staging Brecht's plays.

Hans-Rainer John, the head dramaturge at the DT, had written to the BE asking whether the DT could perform the plays by Brecht that the BE did not intend to stage. The BE's head dramaturge, Joachim Tenschert, wrote an extensive reply explaining why the BE would not be granting other East Berlin theatres the rights to stage Brecht. His opening position was that the BE was interested in Brecht's complete dramatic output, which was curious in the first place, because the BE had neither planned nor shown any interest in the work that preceded The Threepenny Opera (1928) at that time. Tenschert then made the argument that their policy was not predicated on eliminating competition:

to us, it's not a question of having productions based on a different approach to Brecht's plays running alongside the BE's in Berlin, but of embedding our approach, primarily with our audience.94

He supported this position by telling John that the BE was carefully exploring Brecht's method, which was not ‘simple to adopt’, but required time and training both in the ensemble itself and in the spectators who were learning how to view Brecht's plays.

Tenschert's positions betray some interesting contradictions. While no one would begrudge the BE its desire to develop its understanding of ‘Brecht's method’, he, like Weigel did to Heinz, treated the BE's approach as if it were the only legitimate exegesis. Consequently, his denial of a fear of competition becomes debatable: if the BE were successfully working through Brecht's method as an unambiguous system, then other Berlin theatres would present either pale imitations or productions which could not be considered ‘Brechtian’. If, on the other hand, the BE were only pursuing one possible avenue, however effective it had proven, then its implicit claims to authority (and concomitant prestige) would be undermined by success from other Berlin theatres. This exclusivity was based on a belief that the BE was the true heir to Brecht's theory and practice, something that the DT was to call into question (see pp. 199–201, Chapter 7).

The BE's pious veneration of the Brechtian method was satirized by the GDR writer Peter Hacks in a story written in 1961–2 and 1966, ‘Ekbal, oder: Eine Theaterreise nach Babylon’ (‘Ekbal, or: A Theatre Trip to Babylon’). Hacks’ comic allegory, where Babylon stands for Berlin, contains an episode that recounts the death of the Eurasian saint, Bebe95 (Brecht), whose last will and testament decreed the preservation of four qualities in his theatre: ‘greatness, revolutionary power, vitality, and care’.96 The will was distributed to his heirs, but the parchment got lost over time. High Priest Wewe (Wekwerth) retained the exhortation to ‘care’ and had the other three qualities declared heretical. Hacks’ allegory saw Brechtianism as a religion at the BE, the company that dictated its precepts by ‘divine right’. The tendency towards orthodoxy found its confirmation in Tenschert and Wekwerth's reply to John, who had proposed that Theater der Zeit publish their correspondence. They told him in no uncertain terms that they wrote articles and essays when they needed to, and did not publish letters: ‘in any case, the arguments we've presented are nothing new; you can read up on them in Brecht's published writings’.97 Again, a tone of arrogance in communications from the BE is notable, which here masked its own debatable positions.

Interest from home and abroad: confirmation of the Berliner Ensemble's reputation

East Berlin may well have had a special status when it came to staging Brecht, but other theatres in the GDR regularly received BE directors as guests who disseminated Brecht's practice without the sustained preparation upon which Tenschert insisted. The Ministry of Culture had been happy to endorse Brecht's tradition of sending BE directors out to the provinces, and indeed beyond. In 1957, it requested that a BE director stage Mother Courage in Bulgaria.98 A similar invitation for Wekwerth to direct the same play in Moscow arrived the following year.99 Wolfgang Pintzka was dispatched to Görlitz, where the BE was promoting a more regularized relationship with the theatre there in 1960, and three years later, while he was still at that theatre, the Ministry promoted him to Intendant at the theatre in Gera.100 The authorities had found that the BE and its programme of developing young directors could be most useful in a small country with a lot of theatres. Regardless of old ideological disputes, the BE offered qualified, competent directors who could be relied upon to deliver.

GDR theatres did not only demand well-trained staff from the BE. The Modellbücher were also much sought after. This was a very different situation from that which had confronted Brecht on the publication of the Antigonemodell in 1949: he sold fewer than 500 copies.101 This dispiriting statistic probably cooled Brecht's ardour and led to the fact that the Courage and Galileo Modellbücher were only published after his death. The BE's unpublished in-house Modellbücher were certainly in demand in the late 1950s, on the back of both the BE's international success and the surge of interest following Brecht's death. Statistics compiled by the BE show that in the years from 1964 to 1967, the company sent the Modellbücher of twenty-three different productions to 165 theatres. Sixty-three remained within the GDR, twenty-nine went over the border to the FRG, and seventy-three were sent further afield to Europe and beyond, to Cuba, Argentina, the USA, Turkey, Ceylon (as was), Israel, and Egypt.102 The BE also received 729 visitors to its archive from 1964 to 1969, just under half of whom came from the FRG and the rest of the world. The company found it difficult, however, to deal with so many people, and this was noted as early as 1961 when the need to create an ‘Overseas Section’ was mooted to relieve pressure on the BE's dramaturgy department.103 The Ministry of Culture was so keen to cultivate foreign interest in the BE that it proposed the idea of a ‘Brecht Scholarship’ to support theatre people from abroad to work at the BE for 1–2 years. Two to three places were to be offered each year, although the Ministry actually wanted to sponsor more. The BE was cautious about overstretching its own resources and suggested the lower figure.104

High-profile and innovative theatre-makers also wanted to direct at or bring shows to the BE. The archive shows that Jean Vilar offered to stage Brecht's Turandot in 1963, Peter Brook registered his interest in directing something from the English canon through Kenneth Tynan in 1966, and Luigi Nono proposed staging his Floresta in 1967.105 Weigel wanted to invite the Living Theatre in 1964, on the back of their winning a prize at the Théâtre des Nations in 1961 for their production of Brecht's Im Dickicht der Städte (In the Jungle of the Cities).106 The Ministry later reported that it had nothing against the experimental company playing at the BE,107 although Bork also handwrote a simple ‘nein!’ next to the proposal for a production by Brook.108 As it turned out, none of these guests actually worked with or at the theatre, and one can only speculate that either the expense of buying hard foreign currency to pay the guests, official politico-aesthetic objections and/or problems with schedules led to the failure of realizing these ambitions.

The explosion of domestic and international interest in one of the world's most exciting theatre companies was based on its concrete achievements, as demonstrated by its productions in the GDR and on tour. However, this work had to be sustained in order for its reputation to remain tangible rather than to slip into theatre lore. One solution to this was to produce more regularly and to diversify beyond the limits of Brecht's dramas while retaining the Brechtian method.

Documentary drama, Heinar Kipphardt, and the GDR: Oppenheimer and the XI Plenum

The reaction to the elephantine gestation period of Coriolan was a new production that spent a relatively short period in rehearsal, a mere three months. Yet Heinar Kipphardt's In der Sache J. Robert Oppenheimer (In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer) was a play that presented the SED with two different, yet unintentionally related problems. The play was one of the major harbingers of a resurgent wave of documentary drama in Germany that sought to approach the complexities of modern life by capturing its contours in factual sources. In this case, Kipphardt drew on the official record of a hearing to determine whether Oppenheimer, the physicist who had managed the US atomic bomb programme from 1942 to 1945, should retain his security clearance in 1954. The problem for the SED was the documentary mode itself: Kipphardt's attempt to render the situation without bias lacked by definition a partisan stance on atomic weapons, the US state and its security apparatus.

Wekwerth consulted the Ministry of Culture for permission both to stage the play and to stage it ahead of the Volksbühne, which had also signalled an interest. He first connected the play to Brecht's Galileo by noting the common theme of the social responsibilities of scientists. He then argued that the experience of the Messingkauf meant that the BE now possessed the techniques to stage conversations, the main mode of communication in the play, as engaging interactions. His final point was that the BE had registered its interest first.109 The Ministry wrote in a memorandum that the play could indeed be produced in the GDR if it was thoroughly historicized.110 That is, the play was written in the West for Western audiences and was more about Oppenheimer's morals than the political context that brought about the hearing and the decision it reached. In short, the Ministry, internally at that time, was in favour of a thoroughly Brechtian approach to the material. An anonymous report in the Central Committee's archive unequivocally favoured the BE as the theatre best prepared to stage the play ‘with the necessary distance and criticism’.111 Even Walter Ulbricht backed the BE over the Volksbühne on this production, which says something about how certain aspects of the Brechtian tradition had bedded down in the circles of power by the mid 1960s.112

Kipphardt himself brought an amount of ideological baggage to the discussion as well. He had previously been the head dramaturge at the DT, but illegally left the GDR in 1959 after SED interference in the DT's repertoire and adverse criticism of one of his plays. Kipphardt was, in the SED's language, a ‘Republikflüchtling’ (an ‘escapee from the Republic’), and Kurt Hager, the most powerful figure in cultural politics from the early 1960s until 1989, banned his entrance to the GDR in 1964.113 Kipphardt's status as persona non grata did not, however, automatically disqualify the play from performance, and sometime afterwards, Hager's decision must have been rescinded, as BE documentation shows that Kipphardt attended rehearsals on at least five occasions.114

The nature of the production process seemingly suggested that the BE and the SED were singing from the same songbook: the need to historicize and politicize the neutrality of documentary drama was key. Ruth Berghaus, who was one of the two directing assistants assigned to the process, noted: ‘the mode of delivering the speeches is to be derived from the Haltungen, not from the speeches. The words that are spoken are the product of thought processes’.115 Directors Wekwerth and Tenschert were thus interested in creating tensions between word and Haltung. They wanted to open up Kipphardt's documentary dramaturgy in order to reveal the political attitudes that underlay it. Wekwerth also wrote that the production as a whole was an experiment in which the BE had chosen a special form, that of the drawing room drama, in order to generate a lightness in the acting.116 The intention here was to contrast the apparent ease of speech encoded in the hearing's protocol with the hard facts at the heart of nuclear research and its practical consequences.

The production's historicizing approach only converged with the SED's up to a point, however. The team acknowledged that productions in the West had been criticized for how sympathetically Oppenheimer and, conversely, how negatively the FBI could be portrayed. In the interests of dialectical realism, the BE wanted to redress this balance by showing that the USA had ‘a certain right to the atom bomb’ and that that made the decision to deny Oppenheimer clearance all the more difficult.117 Such a reading, that sought to give the hearing realistic depth, simply did not condemn the USA clearly enough for the SED, and this would lead to problems after the East German premiere on 12 April 1965.

The BE nonetheless retained its critique of Oppenheimer, and reused the etched copper walls of the 1957 production of Galileo (see Fig. 6.2) to suggest a connection between the two scientists, an idea reportedly supplied by the celebrated Italian director of Brecht, Giorgio Strehler.118 Wekwerth wanted to portray Oppenheimer's scientific greatness and his historical limitations. The production was well received. In the East, a reviewer noted how the documentary aesthetic had not been punctured by the BE's approach, ‘but brought out in its sober poignancy’.119 Another praised how the BE avoided the temptation to make the production more sensuous or emotional, and enjoyed the ways in which the verbal relationships and the Haltungen did that work amply.120 Western critics were also positive. The title of one review, ‘Without an Anti-American Edge’, reflected the BE's insistence on the production's realism.121 Others noted how producing a play by a Republikflüchtling in the GDR went hand in hand with the permission to stage recent productions of potentially controversial work like Peter Weiss's Marat/Sade and Rolf Hochhuth's Der Stellvertreter (known as both The Deputy and The Representative in English).122 The West welcomed a cultural thaw. This, however, did not last long.

Fig. 6.2. Intertextual set design: copper walls from the 1957 production of Galileo implicitly criticize the nuclear physicists. In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer, April 1965.

Between 16 and 18 December 1965, the Central Committee of the SED held its eleventh Plenum, a meeting that was originally supposed to consider economic issues, but instead turned its attention to cultural politics. It has gone down in GDR cultural history as a significant turning point, a very public re-establishment of the SED's power in this field.123 Shortly before the Plenum, a lesser-known meeting took place, and it was there that Kurt Hager roundly criticized the BE's production of Oppenheimer. He asserted that it lacked ‘any real class perspective’ and was a play ‘that blurred any demarcation of fronts’ by viewing the USA and the USSR as equals, both seeking nuclear weapons.124 Kurt Bartel dovetailed the critique with his contention that the play was written by a traitor, something that the BE's Helmut Baierl disputed.125 Walter Ulbricht countered that Kipphardt's status was irrelevant; the problems were down to the BE's unwillingness to cut the play ‘correctly’.

While the main attacks in the Plenum itself affected the GDR's film industry, theatre was not entirely untouched. The two main targets were Peter Hacks’ Moritz Tassow and Heiner Müller's Der Bau (The Building Site). Ernst Schumacher notes that the mostly unreported third play was Volker Braun's Kipper Paul Bauch (Trucker Paul Bauch).126 This drama had been developed and rehearsed at the BE, but found its rehearsals halted in the wake of the Plenum on 12 January 1966. Attempts to revive the process later in 1966 and 1969 came to nothing.127 Two days after the Plenum ended, the Ministry of Culture set about formulating policy. It requested information on Bauch and asked which measures could be taken to remove ‘ideologically false positions’ in Oppenheimer.128 The BE, however, was given the right to reply and responded not to the Ministry, but to the Central Committee's Cultural Department. The BE's local party leadership concluded that the production did not generate ‘negative effects’ and should thus be neither changed nor cancelled.129 The arguments seem to have worked, and the production continued to be performed until mid 1969.

The Central Committee had played an important part in both the banning of Müller's The Resettler and the removal of Wolfgang Langhoff from the DT's leadership in the wake of 13 August 1961. Yet the unambiguous direction of the Plenum for cultural policy as a whole marked an apparent return to the ‘bad old days’ of the early 1950s, when central intervention was deemed necessary to ensure conformity. Minister Hans Bentzien lost his post in January 1966 and was replaced by Klaus Gysi in a bid to curb the liberal agenda that had briefly crept into GDR culture. However, despite the Plenum, the BE was nonetheless given the opportunity to account for itself, the Central Committee at least tolerated its arguments and did not cancel Oppenheimer. The more prominent presence of the Central Committee in late 1965 heralded its greater involvement in ‘difficult’ matters and decisions in the future, as Wolfgang Langhoff and the DT had already experienced to their cost earlier in the decade. It would thus present an additional layer of supervision to that of the Ministry when the BE entered its most serious and sustained crisis in the second half of the 1960s.