“So, I think it was a sort of choice: to be part of the solution or to be part of the problem. And my option was to be part of the solution.”

Noémie was born in the south of Rwanda in the early 1960s (Interview #18, July 2009). She attended the National University of Rwanda and majored in sociology, got married, and became a teacher. When the genocide broke out in 1994, her husband was killed. As she described it:

I was married to a successful man. [I thought] he will give me anything, do everything for me. But after the genocide it was different because my husband was dead. And I was the head of the house. So, I had to do everything that was the same for the kids as when their dad was around. They must have [the same things] when only I am around.

Noémie recounted how she joined a widows’ organization in the aftermath. For three years, she worked very hard for that organization, and as she put it, “people were really getting to know me.” Soon, people in her community approached her and encouraged her to join politics. She described how she “used to really hate politics, because I thought politics was just a bunch of lies.” But after the death of her husband, she felt motivated to make a difference:

So, I thought about it and was like, alright! Why can’t I join politics and even help out my country? So, I joined politics and was appointed to be the [head of a sector]. By that time I was the head for three years … And then I went to elections for the mayor … I was the mayor for three years, and then I left the mayorship to join [Parliament].

Noémie’s transition from being a teacher to a member of parliament (MP) exemplifies the way that war can serve as a period of rapid transformation in ordinary women’s lives. With her level of education and status as a widow, Noémie was biographically well positioned to take a leadership role in a grassroots organization; from there, she had the network and visibility necessary to run for political office.

While Noémie ended up in Rwanda’s highest legislative body, hundreds of thousands of other Rwandan women also experienced shifts in their political engagement that manifested in less formal political spaces during and after the violence. In what follows, I examine the impact of the violence in Rwanda on women’s informal and formal political participation. As explained in the introductory chapter, I conceptualize informal political participation as occurring in neighborhoods and communities, through nonhierarchical forms of organization and without substantial resources. Women’s informal political activities often revolve around practical gender interests and everyday struggles. While not political actions in and of themselves, as more women engage in such activities they can accumulate, leading to the formation of community organizations that can eventually have an impact on formal political processes. In contrast, the formal political realm is centralized, highly institutionalized, and resource-intensive; it consists of interactions with the state and its appendages. The boundaries between the two realms are not always clear, however, as informal political participation can culminate in formal political change. Here I analyze both, as well as their intersections.

The violence in Rwanda brought about women’s mobilization in many social arenas, from the grassroots to the national political realm. Before long, women’s ordinary activities in new social roles reflected a “politics of practice,” whereby women’s everyday efforts to establish normalcy in conditions of chaos ultimately manifested in political change (Bayat 2010). I understand these new activities as political because they represent the first stage in the broader process of political engagement. For Noémie, these everyday efforts included that she “had to do everything that was the same for the kids as when their dad was around.” As I show in what follows, and in parallel to Bosnian women’s experiences, millions of Rwandan women found themselves taking on new roles to improve their lives and the lives of their family members, and in the process broke cultural taboos. Testifying in local or international courts about rape and sexualized violence they had experienced was also part of this shift. These everyday actions challenged the gendered division of labor and social expectations about women’s place in Rwandan society.

Next, I describe how these shifts facilitated the rapid formation of grassroots community-based organizations (CBOs) in the country. Women took the lead in establishing and running these organizations. While many organizations were “feminine” in nature and concerned primarily with advancing practical gender interests associated with day-to-day life, they also catalyzed women’s increased presence in public spaces and represented new arenas for women’s collective action. For Noémie, participating in a grassroots widows’ organization gave her the network and visibility she needed to run for political office. Soon, many of these groups shifted from working on emergency relief to advocating for women’s legal and political rights. As INGOs and government institutions attempted to reach Rwandans, they partnered with these grassroots organizations to implement programs, disperse funds, and mobilize citizens. This initiated a process of “institutional isomorphism” (DiMaggio and Powell Reference DiMaggio and Powell.1983), whereby fledgling CBOs mimicked the set-up and structure of the larger and more formal NGOs and INGOs they sought funding from – a process that also occurred in Bosnia, as I discuss in Chapter 7. As their missions expanded, these organizations institutionalized a system of female leadership at the local level and eventually provided a platform for some women to launch careers in formal politics.

Finally, I conclude this case study by illustrating how the violence precipitated women’s participation in formal political capacities. Unlike Bosnia, Rwanda experienced a wholesale political transformation after the war and genocide. The regime responsible for perpetrating the most egregious forms of violence was on the run, which left thousands of political offices vacant at all levels of power. The new political elite, led by Paul Kagame and the Rwanda Patriotic Front, welcomed women into the political fold. Women who came to lead community organizations and NGOs increasingly interacted with more formal institutions of power, and some – like Noémie – eventually ran for political office. Others entered formal political realms because of their close ties to the RPF party. As I described in the previous chapter, the government was supportive of women’s inclusion in the political process in part because women represented a neutral, less violent type of political actor – although a more cynical explanation is that the RPF supported women’s political advancement because it distracted the international community from the regime’s use of extralegal violence and consolidation of ethnic power. As I explain later, this frame helped facilitate the ascent of Rwandan women in formal political roles.

A “Politics of Practice”: Everyday Politics

As we have seen, women took on new roles in their households and communities as a result of displacement, the loss or absence of their husbands, and the economic devastation of the violence. With approximately 36 percent of households lacking an adult male, women assumed tasks that were previously considered “men’s work,” from milking cows to repairing houses. They maintained traditional caregiving roles – such as finding food, caring for children, carrying water, and gathering fuel – but now had to venture outside of their homes to care for their dependents, since many could no longer subsist on their own plots of land. One parliamentarian described how:

During this reconstruction process, women themselves got very much involved. In the reconstruction process, physically, socially, they were there everywhere. So that’s when I think men came to realize that also women can perform! … Because formerly it was believed that the man would head the family; but after this, women came in and they did even jobs which we formerly believed were jobs for men.

If only a few women had assumed these new roles, such activities would not in themselves have indicated a broader political transformation. Instead, as thousands of women assumed new roles and challenged conventional gender norms, their activities accumulated and had a broader social impact.

Before long, such activities shifted conventional social expectations for women and showed men that “women can perform” (Interview #11, MP, July 2009). Rose Kabuye, who served as mayor of Kigali immediately after the genocide, described one example of how this process unfolded:

Construction is the biggest industry [in Rwanda]. Well at first the women were shy, and at first they even just did cleaning, sweeping, giving out something. But then they started climbing. And putting stone on, and doing painting, and I remember the President was surprised and he said, “the women, they put on shorts!” – when usually they wear, you know, the skirts. So that is how it started. And then later they started going into business, they took over the tiny businesses … I mean genocide, yes, but the women became hardened, and they wanted to live, and so they have survived. And they took over roles they never had done. They became managers, they became builders, they cut grass, they did everything.

Rose describes how women took on men’s roles, made cash income, and even shifted their type of dress away from traditional cultural expectations. The significance of women wearing shorts or pants arose in many of my interviews; by wearing pants, women could climb, which allowed them to repair their houses and roofs.1 Before long, some women owned and managed their own businesses, leading many in their community to understand them as capable.

Other political elites I interviewed also suggested that women’s participation in tasks previously considered “men’s work” eventually culminated in political shifts. Since housing was a primary concern for millions of Rwandans, women’s involvement in rebuilding houses meant that they were directly participating in the country’s recovery and rebuilding project. The same parliamentarian mentioned previously also described:

[People] had to participate themselves, to contribute, maybe making bricks, providing labor. So women got involved, and you would see a woman starting to construct a house! You know? They had never done it before. And I think when the people were involved in the government, when they saw that also women can do it, that’s when they said, also these women should have a share.

As this MP described, ordinary activities like making bricks or repairing a house reflected an initial step in transforming social expectations about women’s status in society. Women went from being farmers and housewives to being perceived by the state and the whole population as crucial for the country’s recovery. As hundreds of thousands of women participated in such activities, other forms of political action began to materialize.

New Activities through Civil Society Organizations

“Civil society itself was just a band of women who organized themselves. No one gave them the positions; it was just women who showed up”

In villages and neighborhoods across the country, women began to form informal self-help groups to distribute the burden of these new responsibilities.2 Despite restrictions on political space in the aftermath of the violence,3 the organization sector in Rwanda grew rapidly as widespread demographic and economic shifts created urgent needs among the population. These needs were particularly acute for women, who often found themselves assuming new roles, caring for expanded families, and controlling household income for the first time in the absence of their spouses. Organizations ranged broadly in structure and mission. Some were small, informal groups of women that lacked funding or an articulated mission to help women meet their basic material needs. Other, more formal organizations eventually helped women lobby local officials for land rights or trained women to run for political office.

Before the civil war began, merely a handful of organizations existed in Rwanda, and most were tightly linked to the Habyarimana regime; by 1997, women had formed perhaps 15,400 new organizations across the country (Newbury and Baldwin Reference Newbury and Baldwin.2000; Powley Reference Powley2003). By 1999, a study by Réseau des Femmes found 120 women’s organizations operating at the prefectural level, 1,540 at the commune level, 11,560 at the sector level, and 86,290 at the cell level (USAID 2000: 19). As a report put it at the time, these “grassroots civil society associations tend to be small, locally based with few ties to national-level organizations, and formed by neighbors and kin living on the same colline (hill) who know each other” (USAID 2000). In what follows, I describe some of the different types of organizations women formed.

Support Groups

Linda (Interview #48, July 2012) grew up in a rural part of Rwanda, but in 1988 moved to Kigali with her husband. She was thirty-one when the genocide broke out. Because she was Tutsi, Linda fled the city; but her husband – also Tutsi – was killed. Trying to survive, Linda stayed in the bush for several weeks. There, her muscles atrophied because she was too scared to move and lacked food and water; she became too weak to walk. Génocidaires killed her family and many of her friends and neighbors. She survived, but suffers from serious physical disabilities and found herself alone after the violence. As she put it, “When you lose hope, and lose all your loved ones, you have no one to talk to.” But she began to notice people in her area – mostly widows – who “came together to console themselves.” As she grew a bit stronger, she began to join them, “so [I] could have people to talk to, friends.” These groups were incredibly important for Linda and they helped her emotionally and financially recover. Today, Linda is a member of an income and loan savings cooperative, in addition to several larger survivors’ organizations. She credits all of them with helping her survive and reclaim her life after the violence.

Linda’s experience suggests that emotional support organizations drew women out of the private, domestic sphere and into a more public one, eventually linking individual women’s pain with larger social networks and support structures. Many emotional support groups formed organically, as women met in line to collect food from relief organizations, or in IDP or refugee camps. Women with some education or skills often took the lead and helped others in their communities to care for their kids, attain food, repair or build homes, and find schools and medical care. Like I discuss in Chapter 7 in the context of Bosnia, having tangible, immediate goals allowed women to organize around concrete problems affecting their lives. Without the social networks they had before the violence, women used organizations to make connections. In short, organizations formed because women “all had the same problem” (Interview #25, July 2012) – and they needed to survive and improve their lives.

Avega-Agahozo, Rwanda’s largest widows’ association, exemplified an organization that initially formed to provide women emotional support. The director of Avega described how after the genocide, a group of widows from Kigali would run into other women and say, “‘Oh, you survived too!’ So they took an opportunity to meet … Women came together just to cry” (Interview #23, July 2012). According to a former director of the organization:

The first thing that we wanted to take care of and “repair” was ourselves, because everything had been destroyed. We had lost our families. We ourselves were torn apart, so we needed to take care of each other, so that was the first priority, to be able to take care of each other. The first need was emergency relief; then it was taking care of people’s rights, especially the rights of women with inheritance.

Over the next few years, as this woman suggests, the mission expanded; the founding widows decided to help other women and children in their community obtain access to health care, trauma counseling, and eventually legal resources to secure their property. As the group secured funding from donor organizations, it grew rapidly. By 1999, more than 1,500 women had turned to Avega for emotional and social support.

Avega, like the majority of grassroots women’s self-help organizations in Rwanda, does not identify as a feminist organization. Such organizations do not explicitly aim to challenge traditional patriarchal society or dismantle the gendered status quo; instead, they often essentialize women’s roles as nurturers or as peacemakers because they are rooted in the understanding that women’s primary responsibility is to preserve life (Kaplan Reference Kaplan1982; Taylor and Rupp Reference Taylor and Rupp.1993; Stephen Reference Stephen1997). Regardless, these organizations reflected an emerging “female consciousness” (Kaplan Reference Kaplan1982) centered on the shared sense of struggle to survive in the aftermath of atrocity. Further, they offered a space for the development of collective solidarity. Many women who participated in emotional support groups reported that they started to realize that their own suffering paled in comparison to the suffering of others in the group. Because of this, many indicated they were inspired to help other women, children, and their country move forward.

Income-Generating Groups

Chantal (Interview #45, July 2012) grew up as a member of Rwanda’s diaspora in DR Congo. She was poor and had little access to education while abroad. She returned to Rwanda in 1996 after the war, but knew few people beyond her husband, who worked as a primary schoolteacher. She described how she would just stay at home all day with no friends. Soon, however, she noticed small groups of women meeting regularly in her area and decided to join them. By joining, she regained her faith in God, since she heard stories from survivors about what they had lived through during the genocide and war. She was so relieved that she had not experienced such suffering herself and became motivated to make a new life in Rwanda. The group soon began to collect small amounts of money from members each week in order to loan larger chunks of money to members for various projects. Soon, the group loaned Chantal enough money to buy an assortment of fabrics. Chantal enjoyed selling the fabric, so she started a business. After several additional loans from the organization, Chantal had a reasonably successful fabric business in place. Combined with her husband’s income, she has been able to send all six of her children to primary school, and most of them to secondary school when money allows. Chantal is extremely proud of this, especially since she had little formal education herself. Her experience reveals how participating in a community organization allowed women to engage in wage labor outside of the domestic realm. It also illustrates how savings cooperatives offered women control of surplus income for the first time.

Organizations that were initially “for discussing … [women’s] sadness, [the] hard situation they were facing after losing their husbands,” soon transitioned into income generators (Interview #35, MP, February 2013). INGOs frequently funded microcredit projects, which encouraged some women’s groups to shift from self-help and emotional support to vocational-training and profit-marking activities. Women soon realized that by joining together and establishing a formal organization, they could become eligible to receive economic benefits from INGOs, larger domestic NGOs, or the government. For women to receive small grants, they usually had to be members of a community organization; and, for a CBO to be given funds, it needed to register with local authorities and develop a leadership structure. This required members to elect a president and vice president, draft a mission statement, prepare a budget, and so on. Like in Bosnia, this process of “institutional isomorphism” (DiMaggio and Powell Reference DiMaggio and Powell.1983) led emergent grassroots organizations to mimic the structure of the larger NGOs they sought funding from and thereby formalized women’s leadership.

From Grassroots Organizations to Local Politics

Cherise was twenty-seven and living in Western Province when violence erupted in 1994 (Interview #6, June 2009). Just before the genocide, she had gotten married and had a child. During the violence, however, her husband, parents, and most of her siblings were killed. She found herself caring for fourteen children, only one of which was biologically hers. Most were the children of her siblings who had been killed. With a degree from the National University of Rwanda obtained before the violence, Cherise found herself in a better position than many other widows. As she saw it, all women faced difficult circumstances after the war, and “found themselves in the same situation of having to fulfill responsibilities that they never thought that they would have.” Cherise used her education and social network to bring together a group of other widows. Some of these women had lost husbands in the genocide, while others “found themselves alone because their husbands had participated in the genocide and found themselves in jail.” Others still had husbands who were off fighting with the RPF. They began meeting regularly. Cherise described how:

The first activity was to help those who were sick. In the beginning, when we first started to organize ourselves, we were immediately needed on an emergency level to help … and so there was emergency relief, but also trying to reunite families together, mothers and children. Those were our first activities.

Cherise helped reunite families, a task that put her in direct contact with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the UNHCR. Through these activities, her social network expanded. The group of women she worked with also grew, and they began working with other women’s organizations to “organize around the rights of women” and eventually fight to reform the legal code that prevented women from inheriting land. As Cherise described, before long women in her community realized that “we have more in common than we had differences, and we were facing the same challenges, and we needed to get together to move forward.” Working for the women’s organization helped Cherise build confidence and motivated her to seek broader influence. In 1995, she started working full-time at Pro Femmes/Twese Hamwe, an umbrella organization for women’s groups. She attended several INGO trainings that aimed to teach women about their political rights and how to run for political office. Several years later, Cherise was elected mayor of a large district. As she put it:

For every bad thing that happens, there can always be one good consequence. One of the positive effects of the genocide was that we could not see what was happening and just stay there, so we were faced with an incredible choice, and we had to make the decision to do something … I entered politics, because I wanted to do something to help women.

Cherise continued describing how women were uniquely victimized during the violence, as they had watched their loved ones killed in front of them. As she explained, “we found ourselves with the heaviest burden.” This motivated her to do something to help women, because, “when you help a woman, you also help a family, because most times women are less selfish than men … I believe that I can make a difference.”

Cherise’s experience reveals the impact of several of the shifts discussed in the previous chapter. She found herself as the sole income earner in her household, which had inherited fourteen orphans. The suffering she saw around her motivated her to help others. Moreover, she saw women as suffering in a unique way due to their status as mothers and as caretakers of their families. Her early actions in community organizations connected her to larger and more well-connected organizations and INGOs. Eventually, she successfully pursued a career in government.

Who Joined? Who Led? Why?

While no comprehensive data exist that can shed light on the women who founded and led these grassroots organizations, my data suggest that most were Tutsi with secondary or university education. Women with some education or skills (e.g., ability to read and write, nursing, weaving) were particularly influential in helping to establish and formalize income-generating organizations (Zraly, Rubin-Smith, and Betancourt Reference Zraly, Rubin-Smith and Betancourt.2011: 260). At the membership level, however, organizations included women of a wide range of backgrounds – including Hutu and Batwa women. At any level, participating in these newly forming institutions brought women into public and community spaces, increasingly their visibility and linking them with new social networks, government officials, and even international actors. The women who led these organizations became well known; one study found that 50 percent of the members of two large widows’ associations held leadership positions in their communities (Zraly and Nyirazinyoye Reference Zraly and Nyirazinyoye.2010). Women’s participation in these organizations increased the visibility of women in public spaces and leadership roles.

International Organizations Incentivize Grassroots Organizations to Formalize

While the earliest women’s organizations were informal and provided solidarity and support to those affected by the genocide and war, some then shifted to income-generating activities, and before long, some began to focus on advocacy issues at the local, regional, or national levels. Land rights were the most urgent issue at hand. This more overtly political type of organization was often developed in consultation with larger organizations, INGOs, or humanitarian organizations, which provided a vocabulary and framework for speaking about women’s empowerment and gender rights. For example, after 1995, INGOs often referenced the Beijing Platform of Action, which established a global agenda for women’s empowerment.4 In my interviews, Rwandan women who had founded grassroots organizations referred to these international legal frameworks as “tools” they could use to justify their activities to spouses and community members, or in conversations with members of government.

As grassroots organizations began to apply for funding from the government and from INGOs, some gradually formalized. Women who were formally self-subsistence agriculturalists or teachers or housewives found themselves with official titles like president or secretary of the organization. These formal leadership positions had profound implications for their community status, self-esteem, and ability to enter politics. For example, Odette, a genocide widow, was living in Eastern Province after the genocide (Interview #23, July 2012). She “saw so much need … widows were really suffering; they needed houses, food, health care.” In 1995, she organized a group of several other widows from her area who had lost their homes during the genocide. Together, they approached a representative of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and requested iron sheets that would allow them to rebuild the roofs of their homes. The representatives at the UNDP listened and eventually provided them with the requested materials. Encouraged by their success, Odette and the group of women decided to officially form their own organization and apply for additional funding from international sources. They named their organization, wrote a mission statement, and elected Odette as president. This title granted Odette a formal leadership position in her community and gave her a credential she eventually leveraged to join a prominent national NGO.

In sum, many women realized that, in order to fully benefit from the humanitarian aid pouring into the country, they needed to be members of an organization. As I discuss in Chapter 7, a similar process occurred in Bosnia. Foreign funding helped women in Rwanda formalize local organizations and gain a voice in public spaces and leadership. INGOs prioritized housing, health care, and income-generating projects for widows and orphans, as well as organized “trainings” and paid locals to participate.5 Through this process, many ordinary Rwandan women served as interlocutors between their communities, local government, and international funding organizations.

From Informal Organizations to Overt Political Action

Like in other countries around the globe, community organizations became the primary mechanism through which women in Rwanda could stake political claims and participate in public life. There are many examples of how organizations facilitated formal political action. Here I highlight the work of Pro Femmes/Twese Hamwe, a prominent umbrella organization for an array of women’s groups, as it serves as the foremost example of an organization that bridged informal and formal political spaces.

A group of women formed Pro Femmes in 1992 in reaction to the civil war, because they felt that they were:

caught in the tide of the war, and we realized that the primary burden of it was laying on our shoulders, because it was our children who would go to war. It was our husbands who were going to war, and it was us who were left to care and deal with the consequences of that war.

Drawing inspiration from other women’s peace movements around the world, Pro Femmes’ leadership attempted to organize a public march for peace in Kigali in 1992. However, the Habyarimana government shut it down, fearing the march would add to the country’s ongoing insecurity. Not to be deterred, the organizers cut out pieces of paper shaped like feet to symbolize marching women. They wrote, “We want Peace – We want this to end” on the paper feet and posted them all over the city (Interview #5, July 2009).

This early example of women asserting their political voice through the structure of an organization suggests the powerful ability of war to mobilize women’s interests. Unlike Avega, which was primarily focused on social support, Pro Femmes was focused on changing women’s legal rights and substantive government presence. In the aftermath of the genocide, Pro Femmes expanded rapidly, growing from thirteen member organizations in 1992 to more than forty several years later (Powley Reference Powley and Anderlini2004: 157). As it grew, Pro Femmes gained funding from international agencies and frequently hosted consultants from the UNHCR, the UN Development Fund for Women, and other international organizations that provided inspiration and technical training to the organization’s membership (Republic of Rwanda 1999; Burnet Reference Burnet2008; Interview #5, July 2009). In this way, Pro Femmes built capacity to serve as a broker between large international entities and rural Rwandan women’s associations in its network. Through the coordinated efforts of local women’s associations and well-connected NGOs like Pro Femmes, locally initiated campaigns to increase literacy, develop leadership skills, and practice family planning techniques were implemented across the country, all of which were shaped by the international community’s priorities.

Pro Femmes relaunched its Campaign for Peace in 1996. As the explicit project of the burgeoning women’s movement in Rwanda, the Campaign aimed to promote a culture of peace in the country amid ongoing instability (USAID 2000: 20; Burnet Reference Burnet2008: 374). In doing so, the Campaign reflected a shift among women’s groups from emergency relief to a political agenda. The late Judith Kanakuze, one of the women involved with this effort, described how the campaign “was a novel program in which we were discussing how to rebuild society, how to rehabilitate our nation, what is the role of women, and what capacity [do] women need to be part of the solution” (Interview #13, June 2009). The program aimed to insert women’s voices into national conversations about housing, refugees, and justice (USAID 2000: 20). Through the Campaign for Peace, Pro Femmes began working closely with the few women in the transitional government, as well as with the Ministry of Gender and Women in Development in the executive branch. While the campaign reinforced the association between women and peace, it also serves as an example of how women leveraged their “peaceful” identity to serve political ends.

Many of the organizations within the Pro Femmes network next turned their efforts toward land rights. Without legal rights to land or a formalized system of land certification, disputes about ownership were pervasive after the violence. Disputes escalated as hundreds of thousands of “old caseload” and “new caseload” refugees returned from neighboring countries in the mid-1990s. With more than 90 percent of Rwandans dependent on agriculture for their livelihood, access to land was vital (Gervais Reference Gervais2003: 546; Ansoms Reference Ansoms2008: 2). Many returning “old caseload” refugees and landless women – both of whom were predominantly Tutsi – petitioned local authorities for access to communal land, land abandoned by its owners, or less-desirable marshland that was still considered part of the commons (Gervais Reference Gervais2003).

According to many women I interviewed, lobbying local officials through the institutional structure of an organization became one of the only ways women could gain formal access to land (see also Gervais Reference Gervais2003: 547). Centralized organizations like Pro Femmes helped coordinate many of these efforts: it convened meetings with grassroots women’s organizations in order to assess women’s needs and concerns in different parts of the country, and it also worked with the newly formed Forum for Female Parliamentarians (FFRP) and the Ministry of Gender to ensure policymakers heard women’s concerns. Women’s efforts to obtain land rights eventually manifested in a campaign run by Hagaruka, the legal advocacy organization within the Pro Femmes network. In conjunction with women in government, Hagaruka, Pro Femmes, and other civil society organizations lobbied to amend the legal code to allow women to inherit land from deceased family members, as well as to change laws on divorce, property rights, and gender-based violence (see also Mageza-Barthel Reference Mageza-Barthel2015).

One of the key achievements of these efforts was a detailed report recommending that the Government of Rwanda include specific provisions protecting women in the constitutional referendum (Powley Reference Powley and Anderlini2004: 157–158). In 1999, the Organic Land Law and the Succession Law were passed, granting women the right to inherit land and property for the first time (Republic of Rwanda 1999).6 This major accomplishment of women’s mobilization in Rwanda set the stage for subsequent legislation that established children’s rights and protected against gender-based violence (Powley Reference Powley2006; Powley and Pearson Reference Powley and Pearson.2007), although there were major shortcomings of the law.7

For individual women, involvement in these NGO campaigns for peace, land rights, or other goals expanded their social networks by granting them access to government actors or institutions and connecting them to the new regime elite, and equipped them with the vocabulary necessary to speak about gender-specific issues. Some who emerged as leaders in these organizations – like Noémie and Cherise – were actively encouraged to run for political office, and others were hired by INGOs to run various development programs.8 Indeed, participating in informal and formal civil society organizations was the most common “pathway to power” among the forty elite women in government that I interviewed. Of these women, 77.5 percent were involved in a grassroots organization before entering politics; 67.5 percent worked with a more formal NGO or INGO (see Berry Reference Berry2015a). Many MPs credited their exposure to certain social issues while working in these organizations with driving their motivation to influence people at a higher level through government service.

National Women’s Council

The postwar government also contributed to this process of formalizing women’s mobilization. For example, the regime initiated the National Women’s Council (NWC), a system of government-affiliated women’s groups at all levels of government (Interview #2, Inyumba, July 2009). These councils were patterned on a similar program in Uganda, as well as on international women’s councils that emerged in the 1970s. Led by the late Aloisea Inyumba, the NWC was designed as a pipeline through which women’s voices at the base would be heard by the political leadership at the top. To implement the program, Inyumba dispatched a network of party officials to meet with representatives from women’s organizations in each district in the country. These party officials encouraged women to organize into neighborhood councils. Each neighborhood council was then asked to elect representatives to the sector level, where further elections were held to send representatives to the district, provincial, and, eventually, national levels.

According to Inyumba, the structure of the NWC emerged in response to the bottom-up organizing efforts occurring across the country. Eventually, it served as another mechanism for connecting ordinary women to the national governing structure. Women elected to NWC leadership positions gained a formal credential, which they could leverage to launch a political career. For example, after the war, one woman became involved with Réseau des Femmes Oeuvrant pour le Développement Rural (Network of Women Working for Rural Development) and several small organizations in the Pro Femme network, and then decided to participate in the NWC. She described the importance of the NWC to her subsequent activities:

I started at the most local level [of the NWC]; I started at the cell and then I went to the sector, then I went to the district, then I went to the Parliament and so I came here. I was still living in the rural area, so when I joined the National Council of Women it pushed me to move up.

This MP’s experience captures how women’s participation in community organizations gave them the network and credentials needed to later run for leadership positions. At the same time, the NWC was modeled after the hierarchically structured Rwandan state – and thereby served to embed the state into ordinary citizens’ lives.

Formal Politics

While the mobilization of women in the informal capacities discussed earlier was primarily initiated by the war and genocide, another factor enabled this informal political mobilization to translate into formal political spaces. In short, in Rwanda, unlike in Bosnia, the former regime was totally displaced after the violence. Those closely tied to Habyarimana were eliminated – killed, arrested, or forced into exile. The new, RPF-led regime overhauled existing laws and institutions and implemented a political system based on the Arusha Accords. The resulting personnel vacancies at all levels of power offered opportunities for new political actors to enter formal political offices. During the nine-year transition period between 1994 and 2003, the Rwandan government – specifically the Ministry of Gender and the FFRP – worked with civil society leaders to find ways to best incorporate women into politics. At the forefront of this effort was a quota, enshrined in the 2003 constitution, mandating that women hold 30 percent of all decision-making positions. Before long, the regime looked to leaders in communities across the country to fill vacant offices at all levels.

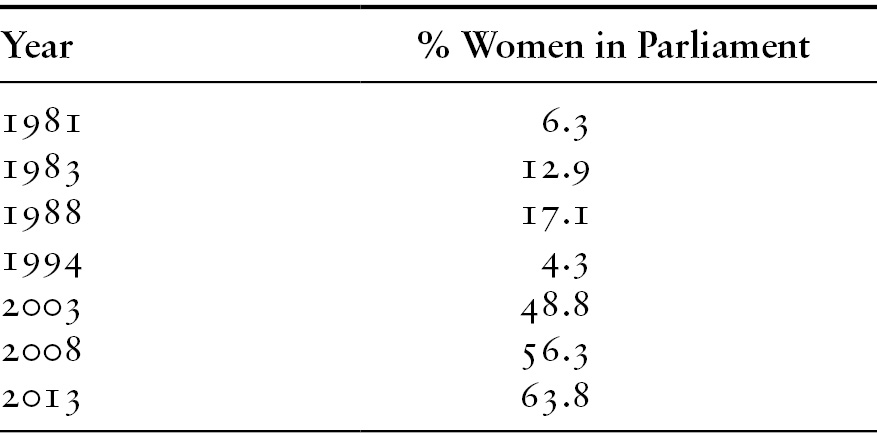

Table 4.1 Women in Parliament in Rwanda

| Year | % Women in Parliament |

|---|---|

| 1981 | 6.3 |

| 1983 | 12.9 |

| 1988 | 17.1 |

| 1994 | 4.3 |

| 2003 | 48.8 |

| 2008 | 56.3 |

| 2013 | 63.8 |

But why was the government of Rwanda so supportive of recruiting women for leadership positions? The reasons for this are debated, but a few are particularly plausible. Most critically, despite the RPF’s success at bringing the genocide to an end, in 1994 most Rwandans distrusted it and considered it the enemy because it was dominated by Anglophone Tutsi who had grown up in Uganda. Many Rwandan Hutu feared RPF revenge attacks, even if they had not participated in genocide crimes. Thus, as the RPF attempted to secure and legitimize its control, women emerged as a large political constituency that the party could safely mobilize in its ranks (see Longman Reference Longman, Bauer and Britton2006; Straus and Waldorf Reference Straus and Waldorf.2011; Thomson Reference Thomson2013; Berry Reference Berry2015a). As discussed in Chapter 3, women were widely seen as less complicit in the genocide and therefore less “ethnic,” in part because Rwandan society is patrilineal, meaning that ethnicity is passed down through male lineage. Thus the RPF could more easily appoint both Hutu and Tutsi women to leadership roles. In this political context, Kagame and the RPF began to vocally encourage women to join politics, often prioritizing the women who were emerging as leaders of local grassroots organizations.

While this promotion of women in government certainly was – and is – part of a broader strategy of consolidating political control, it also reflects the valued place that women held in the RPF movement since its origins in the mid-1980s in Uganda (Interviews, Rose Kabuye, February 2013; Aloisea Inyumba, July 2009). President Kagame in particular has been a champion of women’s rights, describing how “the politics of women’s empowerment is part of the politics of liberation more generally” (Kagame Reference Kagame2014). This “political will” is widely cited by politicians today as a reason for Rwandan women’s advancement in leadership positions. Of course, women candidates who have challenged Kagame’s leadership – such as Victoire Ingabire and Diane Rwigara – have found themselves arrested and imprisoned.

For these reasons, many Rwandan women who supported the RPF’s agenda encountered opportunities to participate in political capacities that would not have been feasible before the violence; yet these women tended to be more educated than average and were disproportionately Tutsi. Of the forty women political elites I interviewed for this project, I estimate that twenty-nine were Tutsi (both survivors and returning refugees), while only eleven made no mention of their victimization during the genocide, and thus were likely Hutu. As I mentioned previously, these figures are estimates; ethnicity is illegal to discuss in Rwanda today, and therefore I was unable to directly ask my interviewees about it and did not seek to verify ethnicity through other avenues.

NGOs played a critical role in facilitating this process of incorporating women in formal political positions. For example, one MP survived the genocide and lost most of her family in the process. In the aftermath, she was desperate to join the RPF, which she saw as saving her and her older sister from a gruesome fate. This MP attended several trainings hosted by Pro Femmes that taught her how to run for office, how to be confident, and how “to know that you are able and you can do whatever you want to do, when you want to do it, as a woman.” She soon ran for a position at the local government level, and won. Motivated by her success, she then described how “when I reached that position I was like I need to go higher up, to where I am now” (Interview #12, July 2009).

Vacancies at the top administrative level of the country also allowed women with long-standing ties to the RPF to assume positions of power. For example, Lt. Colonel Rose Kabuye became the mayor of Kigali City and the late Aloisea Inyumba became the minister in charge of Family and Women Promotion. As I discussed in previous chapters, both women had held prominent roles in the military and fundraising arm of the RPF during its early days and served as visible examples of women’s legitimate presence in politics. Connie Bwiza Sekemana (Interview #9, July 2009) was another early member of the RPF who grew up in Uganda as a refugee. In the early stages of the RPF, she was responsible for working with unaccompanied children and others who were displaced. When the RPF took power, she rose in the party ranks and became a key part of the transition team. Through her position with the party, she worked with multinational organizations like UNICEF on reunifying families after the violence. Eventually, her work with UNICEF was integrated into a government ministry charged with reunification and resettlement, and ultimately this position was folded into the Ministry of Internal Affairs. In the late 1990s, she was transferred again to the Ministry of Land, and then in 1999 was nominated by the RPF to join the transitional parliament. Her experience, like that of many other women in parliament, suggests that closeness to the ruling party is an additional asset in linking individual women to formal political roles.

Several other women became involved in formal politics after holding high-level positions in women’s organizations. Judith Kanakuze, for example, was a pioneer of women’s issues even before the war and became one of the first women to transition from civil society into politics (Interview #13, June 2009). She was an early member of the transitional government and represented the NGO sector as one of three women on the Constitutional Commission. There, she lobbied for the government to incorporate the platform established at the 1995 Beijing Conference into its domestic political framework. Kanakuze became a well-respected gender advisor to several government ministries and her work to mainstream gender-sensitive protocols was key in advocating for the adoption of the reserved-seat gender quota for women in parliament.

Cooption of the Civil Sector

The transition of some women – like Judith Kanakuze – from the civil sector to government, however, was not necessarily motivated by the regime’s desire to empower women. Rather, it appears that it may have been part of a broader political strategy to undermine the strongest voices outside of politics – what Jennie Burnet (Reference Burnet2008: 378) calls an effort to “emasculate” the burgeoning women’s movement. Without a strong civil society – the regime reasoned – there would be little opposition to continued RPF control, and the vibrant women’s movement was among the regime’s first “targets” (Rombouts Reference Rombouts and Rubio-Marin2006). For example, the leaders of Réseau des Femmes, one of the oldest and strongest women’s organizations in Rwanda, resigned their positions in the organization to join the government after 2003. Their departure left the organization poorly managed and it eventually fell deep in debt (Burnet Reference Burnet2008: 379; multiple interviews).

The regime’s strategy of coopting civil society reflects its desire to deeply embed its power infrastructure and ensure its continued control over the country (Mann and Berry Reference Mann and Berry.2016). Moreover, it reflects the growing gulf between the RPF, which is mostly comprised of returnee Tutsi (i.e., those who had grown up abroad, such as in Uganda), and Rwandan Tutsi (i.e., those who had survived the genocide). Rwandan Tutsi were the founders and members of survivor associations, which comprised the most active and dynamic part of the civil sector. The regime’s repression of these associations – and of the civic sector more generally – increased after 2000. Human Rights Watch reported several assassinations of leaders of survivor associations, which were likely politically motivated (Human Rights Watch 2000, 2007).9 The government has also shut down the most independent organizations in civil society, often accusing them of “genocide ideology.” Outspoken human rights activities and champions, including women who were early leaders in the women’s movement, have fled into exile. In short, the rapid formation of community associations and NGOs in Rwanda ultimately did not manifest in a robust civil society that could serve as an effective counterweight to the power of the state.

Conclusion

In this chapter, I illustrated the variety of ways that women engaged in new political roles in the aftermath of violence in Rwanda. Women became involved in various forms of “everyday politics” as they took on new roles and responsibilities in their households and communities. Such ordinary actions began to accumulate, shifting expectations about women’s roles in Rwandan society. As a result of these new roles, community organizations proliferated and became an important space for women to engage with others in their communities. In doing so, these organizations instituted a system of women’s leadership at the local level and furthermore connected ordinary Rwandan women with more formal NGOs, foreign donors, and government institutions. Many women who came to lead these organizations found themselves well positioned to run for political office. With the overhaul of the former regime and the arrival of a new regime committed to advancing women’s leadership, today Rwanda has the highest percentage of women in parliament of any country in the world.

Yet a key question remains: was women’s increased participation in informal and formal politics sustained? Moreover, have the strides women have made at the national political level fundamentally transformed ordinary women’s lives? While the political class of elite women has seen rapid wealth accumulation and the extension of myriad rights, “ordinary” Rwandan women’s stories illustrate a depressing paradox: despite the world’s highest percentage of women in parliament, some of the strongest state-led efforts to promote women, and an entire government apparatus designed with gender equality in mind, profound impediments to women’s equality and liberation are deeply entrenched and appear unlikely to dissipate any time soon (Berry Reference Berry2015b). As I explain in Chapter 8, many of the gains women have made are undermined by the authoritarian nature of the state, in addition to the problematic implementation strategies of foreign NGOs. Further, as suggested earlier, while women have made important strides in many areas, wealthy, foreign-born Tutsi women have disproportionately ascended the national political ladder. As such, new forms of inequality are developing in Rwanda, constraining much of the impressive progress women made in the immediate aftermath of the violence.