Many commentators of The Gift have found the objectives that Mauss sought to accomplish with this publication hard to fathom. In fact, to understand the constellation of meanings surrounding this obscure text, we have to situate it in its proper sociopolitical context: the author was Marcel Mauss; the publication outlet was a sociology journal called L’Année sociologique; the year of publication was 1925; and the city in which it was published was Paris. All of these four markers are important to better understand which goals Mauss sought to accomplish with this publication.

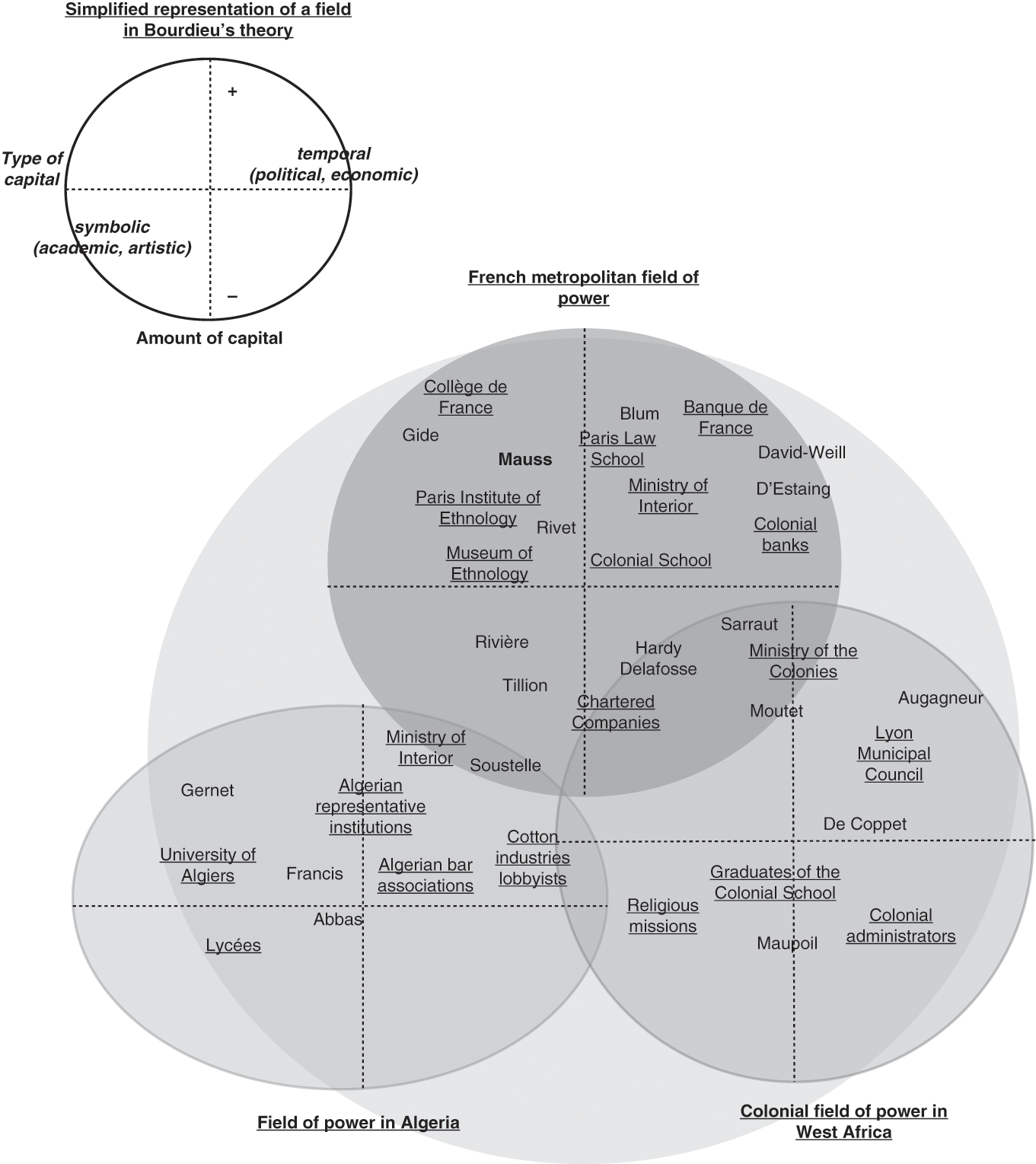

This chapter thus first reviews the situation of Mauss relative to his immediate circles of interpersonal relations at the time he published The Gift, before taking a higher-level perspective, by describing the logics of the French fields of power in the interwar period. Indeed, this chapter shows that, although a classical Bourdieuan field-theoretical approach to intellectual fields is useful to characterize how Mauss and his peers situated themselves in the French field of power, it is also key to situate them at the intersection of the colonial and the metropolitan fields, whose tensions and conflicts determined how The Gift was later received.1

1 Situating The Gift in Its Immediate Context of Reception

The Gift was the product of an accomplished and still rising institution-builder, Marcel Mauss, who benefited, in the words of Pierre Bourdieu,2 from the right type of social capital – economic capital recycled into academic and intellectual capital thanks to his uncle’s mentorship. In 1925, his centrality in the academic field was no longer contested either inside or outside France, especially in the Anglo-American academic worlds. His discipline was in a period of exceptional growth, which resulted both from external political factors – the expansion of the French Empire as a result of the 1919 peace of Versailles – and more local factors – the infatuation of Parisian art collectors for “primitive” fetishes. Mauss was part of these multiple circles which overlapped and accumulated over the years (see Figure 1): the worlds of socialists that agitated the Latin Quarter during the time of the Dreyfus affair, the policymakers and industrial planners during the war, the elites from high finance who were involved in international financial negotiation during the German reparations debate, as well as the colonial administrators and beneficiaries of the colonial expansion who gathered important artistic collections in the interwar period. These partially overlapping circles constituted the readership that Mauss targeted with his polemical essay on the nature of the gift.

Figure 1 Marcel Mauss’s circles of friends and collaborators

In order to better understand the goals that Mauss sought to accomplish with the publication of The Gift, let us start with the first marker: the author. Marcel Mauss was born on May 10, 1872 to a Jewish family which had lived in Alsace-Lorraine, the most eastern part of France, until his father moved to the small town of Epinal (situated in Moselle, France) in order to keep his family French, as Alsace and Lorraine had been annexed by the German Reich after the defeat of the Second Empire of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte in early 1871. Marcel’s father died at an early age, leaving the young Mauss to become a “rich young man,”3 as his uncle, the sociologist Emile Durkheim (1858–1917), wrote to Mauss (his elder sister’s child).

To sum up Mauss’s education and academic career very succinctly: at 21, he came to Bordeaux to prepare the agrégation of philosophy under the tutelage of his uncle, Emile Durkheim – who, being his elder by only fourteen years, was halfway between an uncle and an older brother – and he successfully passed this competitive exam in 1895. Then, in contrast to some of his friends, like Paul Fauconnet (1874–1938), who became a professor of philosophy in a French lycée, Mauss enrolled in PhD studies with Sylvain Lévi (1863–1938), an eminent Indologist and philologist who was a professor at the École Pratique des Hautes Etudes (EPHE) and then at the Collège de France, and who developed a particular fondness for his student Marcel Mauss.4 Although he did not complete his dissertation on prayer, thanks to Lévi, Mauss found a lecturing position at the EPHE in 1901 to teach “The history of religion among non-civilized peoples.” With the interruption of the Great War, which he spent as a translator in the British army, Mauss continued to teach at the EPHE, but also became the Director of the Institute of Ethnology (created in 1926) at the Sorbonne, and in 1931, after several unsuccessful bids, he finally obtained the “chair of sociology” – the first one ever created – at the Collège de France. He taught there until 1940, when he was put into retirement two years early as a result of the anti-Jewish laws passed by the Vichy regime. He spent the war in Paris, with his wife (whom he married in 1934, but with whom he had no children), and died in 1950.

The second part of the equation is also important: the journal in which The Gift was published, L’Année sociologique (L’Année). Indeed, L’Année gives an indication of the first circle of scholars and intellectuals with whom Mauss interacted (see Figure 1), whom he impacted throughout the course of his life. Emile Durkheim was teaching in Bordeaux in 1898 when he founded L’Année, a biannual review which published mostly book reviews surveying the most recent works in German, American, British, and French sociology, history, and anthropology, as well as a few long essays – like the one Mauss wrote with his friend Henri Hubert titled “The Nature and Function of Sacrifice,”5 or The Gift. The scarcity of the essays published in L’Année, coupled with the international diversity of the books that were reviewed, certainly played a key role in the wide reception granted to The Gift in the Anglophone world. Indeed, many prestigious authors, like James Frazer (1854–1941), the famous author of The Golden Bough,6 whom Mauss had met and befriended in Oxford in 1898,7 eagerly expected to receive their copy of L’Année to read their own book’s review: what author would not want to have his book reviewed by young talented Frenchmen who also fought for progressive intellectual causes? As they focused their editorial efforts on producing many book reviews – long before the London or New York Review of Books obtained the recognition they have today – Durkheim and Mauss not only turned L’Année into a formidable vitrine for Anglo-American intellectual production in France, but they were also able to present the French “school of sociology” to the outside world – especially the Anglo-American worlds.

Mauss’s essays were given particular attention as he played a leading role in the editorial team. First, although his uncle was critical of Mauss’s versatility, which had prevented him from writing a single-authored monograph before the First World War, Mauss wrote about 2,500 pages out of the 11,000 pages that were published in L’Année before the war – almost a fourth of the contributions.8 Second, Durkheim relied on his nephew to recruit young progressive Parisian intellectuals attracted by sociology to write for L’Année. Young French academic talent could be found, then as well as now, at the École Normale Supérieure (ENS), and although not a graduate of the ENS himself, Mauss befriended most of the young ENS students during the Dreyfus affair (see Figure 1). The students had publicly asked for the revision of the trial of Captain Dreyfus: a Jewish officer from the same eastern part of France as Mauss, who was declared a traitor and sent to a labor camp by a military tribunal with almost no evidence (and which eventually turned out to be based on forgeries). Although Mauss was on a study trip abroad – first in Oxford and then in the Netherlands, before he returned to take (and then teach) classes at the EPHE in Paris – when the Dreyfus affair broke out,9 when he came back, he met most of the most ardent Dreyfusard intellectuals; he participated in many of their initiatives10 and he enrolled most of them in L’Année.11

Among these Dreyfusard intellectuals whose writings or personal papers I have surveyed to research this book, we can cite: Albert Thomas (1878–1932), a star student of the ENS who was convinced by the famous librarian of the ENS, Lucien Herr (1864–1926, whom Durkheim had befriended in 1883),12 to join the Dreyfusards, and who would later have a strong influence on the group, in particular during the First World War when he became Minister of the Armament and enrolled the whole editorial team of L’Année to work on the war preparation effort. François Simiand (1873–1935) was a philosophy student at the ENS who turned to the analysis of law, society, and economics under the influence of Durkheim and who soon joined the editorial team of L’Année in charge of socioeconomic questions, before becoming, according to Mauss, the “intellectual master”13 of his Minister Albert Thomas during the Great War.14

Henri Hubert (1872–1927) was another ENS graduate and laureate of the agrégation of history, whom Mauss met when the two attended Sylvain Lévi’s class at the EPHE,15 and whose common fight for Dreyfus led Durkheim to call him a “family member”16 – he would later become first the assistant to, and then the curator of, the Museum of Archeology of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Like Simiand, Hubert spent the war planning industrial defense preparedness, with a specialization on the production of tanks, and later remained in close contact with Thomas, establishing connections and exchanging ideas between the latter and Mauss.17

Not all the ENS students who worked for L’Année were close to Mauss: some kept their distance from his overbearing presence, like Célestin Bouglé (1870–1940), who first conceived the project of creating L’Année18 and who founded and directed the Center of social documentation at the library of the ENS. From there, he had a strong influence on the next generation of anthropologists, like Claude Lévi-Strauss, and sociologists, like Mauss’s younger cousin Raymond Aron (1905–83), who worked for Bouglé in the 1930s. Maurice Halbwachs (1877–1945) was another ENS student who had fallen into Durkheim’s orbit, but not under Mauss’s influence. Halbwachs defended a dissertation on housing expropriation practices in Paris, at the same time as he developed a Durkheimian sociology of the working class – before entering the Ministry of Armament under Albert Thomas from 1915 to 1917.19 During the interwar period he turned to topics involving collective memory20 while teaching in the newly liberated University of Strasbourg (in Alsace).21 Hubert Bourgin (1874–1955) was yet another ENS student who had met Thomas and Mauss when they fought for Dreyfus, and also spent the war in the Ministry of Armament.22 These were the men who worked to establish L’Année.

During the Dreyfus affair, this group of politicians, professors, and students multiplied initiatives in the field of publishing and continued education for workers of the Latin Quarter where they studied and taught: they created the Société nouvelle de librairie Bellais where they diffused many tracts on socialism and socialist cooperatives; they created the École Socialiste in the Latin Quarter23 and the Bourse du travail des cours sur le mouvement syndical, which they put in motion from 1898 to 1910. Mauss even attempted to develop joint actions with socialist and non-socialist cooperatives, the latter led by the legal scholar and political economist Charles Gide (1847–1932) – the uncle of André Gide (1869–1951), the famous gay novelist and leading editor who received the Nobel Prize in literature in 1947. Charles Gide was a lawyer by training but also a professor of political economy who would be elected in 1923 to the first chair in cooperative studies created at the Collège de France – and who would later help Mauss get elected to the same prestigious institution. Before the Great War, Charles Gide helped non-socialist cooperatives successfully merge at the European level with the socialist cooperatives coordinated by Mauss,24 and after the Great War, Mauss and Charles Gide crossed paths again, when Gide acted as France’s representative to the Reparations Commission, while Mauss was an editor of the socialist journal Le Populaire, who wrote on the issue of German reparations, as I will explain in the next chapter.25

For a short period, the famous poet, editorialist, and pamphleteer Charles Péguy (1873–1914) joined these young progressive intellectuals, but he soon left the Librairie Bellais after a political and personal disagreement with Mauss and Herr – other sentimental reasons might have been at play, as Péguy later regretted that he could no longer see the young Mauss, whose “elegance and carnation were the dream of [his] sleepless nights, the image of [his] feverish desires.”26 The fashionably dressed dandy whose dissolute life was seriously judged by his uncle Durkheim,27 Mauss made quite an impression on his fellow comrades. In addition to being a young professor at EPHE, he was thus what we would call today an energetic “community organizer,” although one who preferred to coordinate cooperatives across regions and even countries from his base in the Latin Quarter, rather than one who spent time in the South Side of Chicago.

Now, and third, the year of publication of The Gift is also important: 1925. In the small intellectual Parisian milieu, 1925 differed from the prewar years in important respects. By that time, the Great War had taken its toll on Mauss’s generation, and the Third International had split the international socialist movement in two, leaving on one side those who believed in a reformist strategy whereby social change would be accomplished within the existing constitutional framework (thanks to elections); and on the other side, those who followed Lenin and wanted to export the Soviet Revolution to the whole world.

Before the war, Mauss had been a fellow traveler of the French socialist party founded by Durkheim’s friend, Jean Jaurès (1859–1914), whom Durkheim had met when Jaurès was a student at the ENS, where Durkheim prepared for the agrégation in philosophy. Mauss had met Jaurès first in Bordeaux, thanks to Durkheim, and then again during the Dreyfus affair.28 The two men met with a former student of the ENS, Léon Blum (1872–1950), by then a young rapporteur at the Conseil d’Etat (the highest court in administrative law) who wrote the legal defense of Emile Zola when the latter was attacked for libel after publishing his famous Dreyfusard article “J’accuse … !”29 Mauss later contributed (with Jaurès) to the creation of the journal L’Humanité, and from the beginning sat on its board of trustees as one of two representatives of the new political party, the “Section Française de l’Internationale Ouvrière” (SFIO), created by Jaurès in 1905 (see Figure 1).30 These socialists had deep ties to the ENS,31 leading French historians of the socialist movement in France to call their form of socialism “socialisme normalien”:32 even Blum had been admitted to the ENS before being expelled for poor attendance, distracted by his high school best friend André Gide, with whom Blum conducted his poetic and literary endeavors before turning to politics.33

If effervescence characterized the early years of the twentieth century for these young French socialists, the early 1920s were very different from the prewar decade: when Mauss published The Gift in 1925, he was 53, no longer a young man. In fact, the war had turned him into the dean of the Durkheimian school of sociology, as most of the prewar collaborators of L’Année sociologique had died or had left academia. Jean Jaurès was the first French casualty of the war: he was assassinated by a young nationalist a few days before the war broke out, as he was on his way to write an op-ed in L’Humanité in which he planned to defend the cause of peace and call on European socialist parties to unite against the coming war. To cite just a few others, we can mention Mauss’s cousin and Emile Durkheim’s son, André Durkheim (1892–1915), in whom the elder Durkheim had placed his hopes for an intellectual heir, and who was soon joined in death by his father who died of grief in 1917; or Robert Hertz (1881–1915), who was one of Mauss’s best friends among the collaborators of L’Année, and was killed in Verdun. Hertz had been one of the ardent figures of socialisme normalien and like Mauss before him,34 he had gone to study the anthropological school in the United Kingdom – the British later recognized him, through the voice of Edward Evans-Pritchard (1902–73), as the next Durkheim.35 He was gone too.

With the Great War not only did many collaborators of L’Année disappear, but some dreams associated with their cooperativist utopia also died. The utopia they had pursued before the war was strongly influenced by the ideology of “solidarism,” which was developed by a nebula of jurists and legal scholars interested in the notions of solidarity, debt and contract, in which, indeed, one could count Durkheim and Charles Gide,36 but in which Léon Bourgeois (1851–1925) was the most prominent and influential intellectual at the time: Bourgeois was a lawyer by training, an essayist, and the founder of the “Radical Socialist” Party, who became the head of the French government in 1895 – a position he kept only for a short period of time, due to parliamentary opposition to his attempt to pass a progressive income tax (finally created during the Great War). Bourgeois was influential in late nineteenth-century France for diffusing the notion that every individual was born with a “social debt” which they needed to pay back in order to maintain the existence of the social bonds (or solidarity) between individuals of the same nation. Such a moral and social philosophy, expressed in simple terms, asked those who had received more to give back more to society than those who had received less. This principle may seem self-evident now, but it was not so at the time: remember that Bourgeois’s government fell after parliamentary opposition against his proposal to introduce progressive income tax – something that is widely accepted today. After the war, Bourgeois was nominated to be the first President of the League of Nations in 1919 after a long-lasting effort in favor of obligatory arbitration of interstate conflicts in the Hague conferences, an activity for which he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1920, even though some could have argued that the Great War had precisely proven that arbitration was not binding enough to stop conflicts from escalating.

As Mauss was involved in the socialist party created by Durkheim’s friend Jean Jaurès rather than in Bourgeois’s radical party, claims that his intellectual agenda reflected a solidarist inspiration may look like an oddity. But solidarism worked as a loose ideology before the Great War,37 and as Marcel Prélot writes, Jaurès’ socialism, and that of the generation he inspired, was a “quasi-solidarism”38 – just as the solidarist position of Charles Gide was “quasi-socialism,” if socialism, as envisioned by Emile Durkheim, was a “tendency to organize” relations between individuals, firms, contractual partners, and other forms of modern beings associated with the industrial life under the democratic rule of law.39

Furthermore, the socialists and solidarists argued ardently that the cause of peace in Europe was their main priority: they planned to avert a war in Europe by uniting workers across borders and by calling for a general transborder strike of workers in case of an imminent risk of war in Europe. For instance, the French socialists sent a delegation of the Parliamentary Group for Arbitration to Bern, Switzerland, in May 1913 for a conference on Franco-German entente,40 which included important socialist figures like Jean Jaurès and Marcel Sembat (1862–1922) – a close friend of Marcel Mauss and Bronislaw Malinowski,41 who wrote on international affairs for L’Humanité before becoming the Minister of Public Work during the war with Léon Blum as his chief of staff.42 For them, international solidarity between European nations was of higher value than a global communist revolution: at least, that is what French socialists believed until Jaurès’s assassination, which, on the eve of the war, was the electroshock that woke them up from their dogmatic dreams.

Mauss’s prewar actions as a public intellectual had been in fact characteristic of this broad solidarist philosophy. For a decade before the Great War, Mauss defended the cause of European solidarity by intervening in the European “cooperativist” movement, which mushroomed outside the party system and outside the state’s purview to challenge a strict understanding of market operations. These cooperatives abided by a notion of solidarity which was conceived in terms very close to Léon Bourgeois’s normative (and utterly positive) understanding of social solidarity and anchored on such legal notions as the “quasi-contract”:43 solidarity was made manifest by an active mutualization of wealth, contracts, and duties in the sphere of exchange (rather than that of production) by the social groups themselves.44 By forming cooperatives in independence from their state’s diktats, individuals found a way to express their solidarity against the disaggregating forces of contemporary markets. As Bouglé later wrote, in this conception of solidarity, individuals consider that “the State stops being the lawgiver who brings the tables of the law from some distant Sinaï: it is in the river of everyday life, in the current of private law, that the State finds its reason to intervene.”45

The primary purpose of the cooperativists whom Mauss represented was thus not to appropriate the means of production and challenge the state’s authority, which is why Marxists and socialists like Mauss clashed on the value of cooperation for the workers’ cause. The Marxist parties – one of which was headed by Karl Marx’s son-in-law, Paul Lafargue (1842–1911), whom Mauss confronted directly46 – prioritized the goal of bringing down the capitalist system in France, and Germany over all other objectives. Whereas Mauss defended the multiplication of consumer cooperatives, or wholesales, the orthodox Marxists condemned these cooperatives for delaying the coming revolution by allowing workers to collectively bargain cheaper prices.47 Mauss defended wholesales and cooperatives of workers for exactly the same reason: workers benefited from higher living standards by reducing their costs of living and mutualizing resources against the risks of modern life (work accidents, early death due to poor health in urban centers, unemployment, etc.). Furthermore, by participating in cooperatives, workers developed international ties with other cooperatives in Europe, which helped them create solidarities across national boundaries and in relative autonomy from their state’s purview.48

But even if Marxists and non-Marxist socialists clashed before the war, the SFIO had managed to keep various socialist families together before 1914. With the proof that pan-European workers’ movements had failed to stop the war, and with the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the split between Marxists and non-Marxists in the French socialist movement was made official and irreversible – at least until the mid 1970s. In 1920, the prewar SFIO was split as a direct result of the Bolshevik Revolution, and more than half of the socialist party left to form the French Communist party and took with them Jaurès and Mauss’s old journal L’Humanité in their suitcases. Thus, the leading post-1920 intellectuals of the remaining SFIO, Blum and Mauss, kept the keys of the old SFIO and took over another much smaller socialist journal, Le Populaire, to express their minority views on international politics and the need to counter the Soviet Revolution: this journal was partially funded by Blum, Belgian cooperatives, and private donors, and issued 2,225 copies a day when it was first published in April 1921, in contrast to L’Humanité, which issued 200,000 copies a day in 1920.49 As far as Mauss was concerned, he still believed in the solidarist notions of solidarity, quasi-contracts or tacit contracts, which not only found their way into his scientific essays, like The Gift, but also infiltrated his political writings, as in Mauss’s 1924 essay on Bolshevism, in which he criticized the lack of Soviet recognition for the existence of “tacit international contracts”50 between nations bound by debt relations, but he no longer represented the majority view in the left wing of the political spectrum. Thus, the year 1925 marked a time of maturity for Mauss, if maturity can be signaled by the proliferation of younger intellectuals expressing views more radical than one’s own on the main problems of the time.

Fourth, and last, Paris was the place of publication of The Gift. Paris had recently been the center of the world, as the diplomatic negotiations that settled the Great War had taken place there for more than a year. In the mid 1920s, it remained a city of contrasts: it was the capital of an ailing nation, which depended on German reparations to reconstruct the villages and industrial plants destroyed by the war in the former fighting zone; but it was also the capital of booming empire, with newly gained colonies from the Germans – in Togoland and Cameroon – and a new zeal for large-scale ethnographic explorations of the ethnically diverse populations living in its colonies. Paris was becoming the city of the Colonial Exhibitions, of the new artistic movements, with the excitement for the new “Negro art,” which first attracted the small group of artists, collectors, anthropologists, and curators gathered around Mauss and Paul Rivet (1876–1958) – a doctor and ethnographer who specialized in South America, Rivet was assistant curator at the Museum of Natural History in 1925, but was soon selected to be the director of the Museum of Ethnology of the Trocadero in 1928 (which became the Musée de l’Homme in 1937).

Mauss was a direct witness, if not a player, in this artistic revolution. The bridge between the academic and artistic worlds and the world of collectors was facilitated by Rivet’s assistant at the Museum of Ethnology: Georges-Henri Rivière (1897–1985). Rivière, on top of his job at the Museum of Ethnology,51 was also the private adviser of David David-Weill (1872–1951), the director and heir of the Lazard Frères bank in Paris, whose immense wealth was put to the service of art collection, which he donated generously to many Parisian museums (like the Museum Guimet on South Asian art).52 Thanks to these political, academic, and aesthetic transformations in Parisian life, Mauss’s reflections on gift exchange inspired intellectuals and politicians beyond the first circle of socialist and Dreyfusard thinkers with whom he crossed paths before the war. In the mid 1920s, Mauss became actively involved in the institutionalization of ethnology in Paris, at the nexus between academia and French colonial administration. The young ethnologists who worked at the Museum of Ethnology were formed at Mauss’s newly founded Institute of Ethnology in Paris, which finally came into being in 1926 with Mauss and Rivet as its two secretary-generals (see Figure 1).

The creation of the Institute of Ethnology in 1926 allowed ethnologists to serve as a bridge between the aging generation of colonial administrators and reformers to the newcomers in the field of colonial administration. The management of the Institute gathered many eminent scientists, most of whom were well doted in colonial capital: it was codirected by Marcel Mauss, with Paul Rivet and Lucien Levy-Bruhl (1857–1939), a cousin of Alfred Dreyfus, who had befriended both Durkheim and Jaurès at the ENS. But it also comprised colonial administrators, especially in the Council of the Institute, which included prestigious professors at the Collège de France, like Louis Finot (1864–1935), a close friend of Sylvain Lévi, who directed the French School of the Far East (EFEO), one of the most important institutions for the colonial administration of Indochina, and Colonial Governors, like Maurice Delafosse (1870–1926), who also taught at the Colonial School.53

At the Institute of Ethnology, and then at the Museum, Mauss’s students learned how to collect, identify, date, classify, and display the artifacts and fetishes they brought back from their ethnological missions, and they mingled with the art collectors of the worlds of high finance, like the Rothschilds and Lazards, who funded their missions abroad. Rivière, whose sister later conducted ethnographies in Algeria54 with Mauss’s doctoral student Germaine Tillion (1907–2008), organized more than 60 exhibitions at the Museum in less than a decade, some with Mauss’s students, like the South Americanist Alfred Métraux (1902–63), or the Maya specialist Jacques Soustelle (1912–90) – who replaced Rivière as assistant to Rivet in 1937 when Rivière became the director of the Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions. Soustelle was also a graduate of the ENS and among the most talented of Mauss’s PhD students.

This Parisian collaboration, which was based on the exchange of gifts between art collectors, ethnologists, and curators, was fruitful for all. Without it, Mauss’s famous essay might never have been published, as it was thanks to a generous gift by David David-Weill that Mauss published the 1925 volume of L’Année sociologique – the first one published since the end of the war – in which The Gift was printed. David-Weill and other art collectors also funded many of the big ethnographic missions pushed forward by Mauss, like the Dakar-Djibouti Mission (1931–33) led by Marcel Griaule (1898–1956), another of Mauss’s PhD students who toured French Africa from West to East in search of all the artifacts he could put his hands on.55 For Mauss, this was a new world, well suited with his Parisian dandyism, full of energy and optimism for the possibilities offered to French ethnology by the French imperial expansion.

2 Mauss’s Relative Marginality in the French Metropolitan Field of Power

To move beyond the immediate circle of colleagues and friends whom Mauss targeted with the publication of The Gift, and to view the development of their ideas from a higher viewpoint, it makes the most sense to draw on the field-theoretical approach first developed by Christophe Charle and Pierre Bourdieu in the sociology of intellectuals and intellectual fields. Armed with their concepts, we can study how such a publication as The Gift helped Mauss redraw social boundaries between disciplines in the French academic field; and which resources and forms of capital circulated in the academic field at the critical time when the disciplines of anthropology and ethnology were becoming institutionalized under Mauss’s leadership.56

It is remarkable how much the anthropologists, economists and international law scholars who developed Mauss’s ideas on gift exchange and who were part of the overlapping circles already described looked alike in terms of their social capital: most of them were men – until Mauss’s students, indeed all of them were men – often from a bourgeois or at least urban background, and they graduated from the top French public schools like the ENS. Furthermore, they most often represented a subcategory of elites whom Pierre Bourdieu, drawing on the sociology of religion, has called the “heresiarchs”:57 those elites with enough social capital to reach the top echelons of state power, but still not quite to the top, as one key dimension of their identity kept them in a situation of vulnerability.

Most of Mauss’s peers (as cited in Figure 1) were indeed religious minorities, like the Gides (uncle and nephew, both Protestant), or Durkheim, Blum, Lazard, and Mauss, who were all well assimilated Jews or “Juif d’Etat”58 as Pierre Birnbaum has called these “secularized Jews devoted to the public service of their country who … identified completely with the laic universalism of the modern French state,”59 and who attained positions as high civil servants. Their sense of attachment to the elite was fragile, as they knew their standing in the circles of state insiders could be subject to the moods and whims of the long-established Catholic or aristocratic elites who sometimes allied with the mobs to threaten these newcomers. When they did rise to the top, as Léon Blum did in 1936, when he became the head of the French government as the leader of the Front populaire party coalition, they were still vulnerable to the attacks of both mobs and political–administrative elites: in February 1936, Blum survived a lynching when his car got stuck in a nationalist protest, and immediately after his election, he was attacked in the French Parliament by right-wing parliamentarians for being the first Jew elected as the leader of the French government. In 1940, the Vichy government arrested him and put him on trial for treason, before turning him over to the Nazi authorities at the end of the war – which he miraculously also survived, when his group of political hostages deported to Buchenwald was freed by the Allies.60

To give another illustration, one can cite Mauss’s friend, Max Lazard (1875–1953), whom he also thanked for a generous gift toward publication in the volume of L’Année sociologique in which The Gift was published.61 As in the case of Mauss’s trajectory, it is clear that Max Lazard’s career was largely determined by the quantity and quality of social capital he received at birth: he was the son of Simon Lazard, one of the founders of the Paris bank Lazard Frères, and the cousin of David David-Weill, who managed the affairs of the Paris branch during the interwar period (see Figure 1). Marcel Mauss and Max Lazard’s professional development ran along parallel courses, accounted for by a common social background. Both came from Jewish families from Alsace-Lorraine; they were deeply patriotic and attached to the French Republic at the same time as they were very much open to the British and US academic worlds (something not taken for granted at a time when German academia entertained a strong attraction among French colleagues); they fought for Dreyfus’s rehabilitation and conceived it to be their duty to intervene in public debates as experts with knowledge grounded in their discipline; they had key access to insider knowledge thanks to their network of peers as well as their social and family relations. Still, Mauss and Lazard made different choices, and their endowment in terms of economic, social, and cultural capital may account for such differences. Max Lazard did not follow an ambitious uncle in Bordeaux, but found his way to New York thanks to the generous help of his father and uncle’s business partners, where he completed a PhD on economic cycles causing unemployment at Columbia University.62 Later, like many of Mauss’s friends and peers, he entered Albert Thomas’s cabinet at the Ministry of Armament and then followed Thomas to Geneva when Thomas became the head of the newly created International Labor Organization (ILO).

One of Marcel Mauss’s PhD students, Jacques Soustelle, aptly expressed the feeling of vulnerability – or fragile legitimacy – which many of these men felt based on their religious, or rather ethnic, affiliation (as religion was also ethnicity in France): as a Protestant growing up near Lyon, Soustelle read the history of the Reformation when he was 10 and thus learned very early on “that [he] belonged to a minority, that France was his nation [patrie] and that French was his language, but that the French state had often been their enemy.”63 Very few among Mauss’s close circle of friends did not have dramatic firsthand experience of this enmity of the French state during the course of their life. For Mauss’s generation, first came the Dreyfus affair, when anti-Semitism was ardently fought for in the nationalist press and in the courtrooms. Then came the Vichy regime, which first downgraded the civic rights of Jews, and then actively participated in organizing their extermination during the Nazi occupation. The Second World War in particular took a strong toll within Mauss’s circle of colleagues for the precise reason that many of them belonged to religious minorities, especially Jews: most importantly, ten anthropologists who were members of the Musée de l’Homme group, one of the first Resistance groups created in occupied France in 1940, were arrested and executed by the Nazis in 1942: Anatole Lewitsky, Boris Vildé, Léon-Maurice Nordmann, Georges Ithier, Jules Andrieu, René Sénéchal, and Pierre Walter; only Yvonne Odon and Georges-Henri Rivière survived. For her part, Germaine Tillion, another of Mauss’s PhD students, joined the group upon her return from Algeria to Paris in 1940 – she was arrested with her mother in 1942 and deported to Ravensbruck (where her mother died),64 and from where she survived to publish the first ethnographic analysis of the concentration camp system. Paul Rivet, who, as director of the Musée de l’Homme, shared responsibilities in the group, survived the chase by the Nazis thanks to his exile in Colombia and then Mexico, where his former assistant Jacques Soustelle brought him to participate in the activities of the Free France until his return to Paris in 1945.65 Although not Jewish himself, Maurice Halbwachs was killed by the Nazis in the Buchenwald concentration camp in March 1945, after being arrested for harboring his son (who committed acts of resistance and was Jewish according to the Nazis, since his mother was).

Mauss himself survived the Nazi occupation, even living in the occupied zone, without experiencing deportation, which in itself was an oddity: Marcel Fournier, Mauss’s biographer, believes that Mauss benefited from the active protection of either German anthropologists, who appreciated his work on the Germanic tribes and the Celts, or that of the Minister of Labor and Cooperation in the Vichy government, Marcel Déat (1894–1955), who had worked with Lucien Herr and Célestin Bouglé at the library of the ENS before adhering to Blum’s SFIO, before creating a new party representing “neo-socialists,” with the active support of Mauss.66 Still, although Mauss was neither assassinated nor deported by the Nazis, he suffered tremendously from the war years, as did his close entourage: with the first decrees passed by the Vichy government and the Nazis in the occupied zone, he was forbidden from teaching either at the Collège de France or at the Institute of Ethnology, and had to resign from all his functions; later he even had to leave his apartment when it was requisitioned by the Nazis.

As the following chapters will detail, a concern for the perils and dangers looming over the head of Mauss and his immediate circle of friends was never absent from Mauss’s mind, and manifested itself in more minor publications at the time he wrote The Gift: although anti-Semitism was not explicitly mentioned in Mauss’s essay, and contemporary readers would be hard pressed to find any suggestions that the selection of cases of gift exchanges that he surveyed in his essay betrayed a worry for the revival of anti-Semitism in the interwar context, the next chapter shows that such a concern was made clear in his other political and academic essays which he published right before the publication of The Gift. To find an explicit rebuke of the anti-Semitic representation of Jews as greedy individuals unable to give, which Mauss found in social science essays and “political apologies of the most vulgar type,”67 one had to read Mauss’s book reviews in the same volume of L’Année sociologique in which The Gift was published – something that the new edition of The Gift prepared by Jane Guyer will make easier for English-speaking readers68 – in which he denounced the anti-Semitism of German scholars who distinguished “between the societies and classes in which altruistic exchanges are common, and the societies and classes which are parasites of the exchange systems (aristocracies, plutocracies, Jews).”69 Mauss’s editorial choice explains why contemporary readers, most of whom will not read The Gift in the large volume of L’Année sociologique in which it was published, are not conscious that, indeed, these anti-Semitic writings on gift exchange were very much present in Mauss’s mind, and he made a point of attacking them throughout his life.

3 Mauss’s Centrality in the Colonial Fields

Although a classical Bourdieuan field-theoretical approach is useful to characterize how Mauss and his network of peers situated themselves in the French field of power in the interwar period,70 it is also important to move beyond this purely national perspective, as the specific discipline – anthropology – and the specific group of intellectuals – Mauss’s circles – on which it focuses requires us to pay attention not only to the purely metropolitan French academic and political fields, but also to the transnational ties existing between the colonial and the international fields.71 Indeed, as George Steinmetz writes in his post-Bourdieuan history of the German colonial field, any historian of intellectual fields should avoid “the dangers of error due to a nation-state-based approach which are exacerbated in the case of imperial sociologists, many of whom spend a great deal of time overseas in research sites or historical archives, interacting with scholars and laypeople from the colonized population and from other metropolitan nations.”72

In this regard, the creation of the Institute of Ethnology in 1926 not only gave Mauss a way to increase visibility of his approach to ethnography in the French metropolitan academic field, but it was also supposed to give a rightful place to ethnology in the colonial field, from which it had been absent until then. Ethnology had not been a priority for the French Republic before the war.73 Since the establishment of the Third Republic in the early 1880s, the Paris-based Colonial School had been the main center of training for colonial administrators.74 As William Cohen writes, in 1914, “the administrative section of the Colonial School was the first functioning program specifically established to train men [of the metropolis] for civil service positions,”75 who were required to gain at least one year of formal training from the Colonial School. Students were trained in a purely formal and universalist manner, with no attention paid to the local context into which these men would be sent.

Before the war, students in the Colonial School learned accounting, history of French colonization, and Roman law,76 as their professors in the School assumed that “there cannot be ten different ways to organize a family, to conceive of property or of a contract.”77 The emphasis was on legal knowledge: students had to enroll in a Bachelor of Arts in law in parallel to their training at the Colonial School.78 Language requirements were particularly limited (Arabic being the dominant language taught in the School), and sometimes oriented toward languages of little value in the colonial territories. Maurice Delafosse, a former bush administrator was one of the only teachers of African customs, language and history at the Colonial School.79 Furthermore, most of the trainees were metropolitan citizens, as the administration of the School had bowed to the recriminations of the sociologist Gustave Le Bon (1841–1931), who claimed that training colonial subjects in Paris (as the British had done in London) would only excite their passion for national independence and their desire for a modern lifestyle far from their material conditions of life.80 Thus, it was an understatement to say that the Colonial School had little use or regard for the kind of knowledge that ethnography could bring to its curriculum. In the early 1920s, Robert Delavignette, who took over the direction of the Colonial School after the departure of Georges Hardy (1884–1972), a former colonial officer in Morocco, still lamented the fact that “ethnographic reports were considered taboo [by most colonial administrators in the field] and buried away in the administrative files.”81

As far as the field of power in Algeria was concerned, strong resistance also prevented ethnologists from gaining a say in the training of French administrators in Algeria, although the sources of blockage were different in Algeria and in West Africa, as Algeria was a settler colony with a large presence of citizens of the French Republic. Until after the Second World War, the University of Algiers, which provided a large contingent of French administrators in Algeria (judges, lawyers, law clerks, etc.) was strongly segregated between those students who studied French administrative, criminal or civil law in Algeria and who were mostly of European descent; and those students of Arab or Berber descent who remained concentrated in sub-tracks specialized in the study of customary law – Muslim law in the case of Algeria, but also local codes from Kabylia.82 In none of the curricula did ethnology appear as legitimate. Muslim law students from Algiers – where the only school of law in Algeria was created in 1879 – were expected to confine themselves to the study of Muslim law in order to become oukils authorized to plead a case before a cadi in a Muslim court, and students in French law who studied in Algiers did not take an ethnology test.83 As a result, in 1910, only seven out of the 300 lawyers located in Algeria were of Muslim descent (representing a mere 4 percent),84 and forty-five years later, in 1955, that proportion had hardly improved, with fewer than twenty lawyers of Muslim descent out of 400 registered lawyers in Algeria.85

In Algeria, the segregation of the state officials was thus not grounded on any legal discrimination, but on the self-perpetrating prejudices of the educational system and the professional organizations that controlled entry into the legal profession in the colonial field in Algeria: namely, the bar associations of the main cities of Algeria (Algiers, Oran, and Constantine), which maintained a strong boundary between the study of both systems of law: French and customary law. In fact, the Algiers bar association systematically ignored the jurisprudence of the Court of Algiers,86 which, in 1882, had decided that admission to the bar was not dependent upon acquisition of French citizenship by Algerian Muslims: as obtaining the latter required Algerian Muslims to renounce their observance of Muslim laws, the Court had reasoned that it amounted to forced conversion (or at least, a turn toward secularism) unwelcome to most.87 But in the 1920s and 1930s, the Paris or Algiers bars still denied the right to exercise to law graduates from Madagascar, Algeria, and Indochina, who were not full citizens of the French Republic.88 And the situation worsened in the 1930s, in the context of an increasingly competitive legal market, marked by the economic downturn and the naturalization of many European Jewish refugees who practiced law in their country of origin. By then, the bar associations in both metropolis and overseas territories lobbied for even more restrictive conditions on access to legal professions, thus further strengthening the boundary between the serious study of French law and the less interesting study of local legal systems, which they left to the colonial subjects, and to ethnologists indeed in the Institute of Ethnology.89

Confronted with such lack of interest in the contribution that ethnology could bring to the training of French administrators and lawyers in Algeria or West Africa, Mauss started writing letters to the Ministry of the Colonies in the early 1900s, when he lamented “the paucity of interest for ethnography on the part of the state, the public and the learned societies,” which explained why the “entirety of ethnographic work is done by the British and the Americans”90 – but to no avail. Already in 1902 and 1907, after his trips to the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, Marcel Mauss had written memorandums addressed to the Minister of the Colonies in which he appealed (in vain) to the patriotism of the minister to create a “Bureau of French Ethnology similar to the American Bureau created at the Smithsonian.”91 For Mauss, the terrible state of ethnological knowledge in France explained the “multitude of mistakes found in the French literature on the supposed barbarism of the Negroes of Congo,” which stood in “sharp contrast with the work done in Germany by [Adolf] Bastian (who died in the field).”92

In the absence of a national home for ethnology, Mauss feared that French anthropologists and colonial administrators would have to continue to rely on the German institutes to find ethnographic facts, as the latter “not only collect data among populations of German colonies, but also in other parts of the world, including in the French colonies”93 – a fact he underlined to alarm the French Ministry that German ethnography may have ambitioned to administer the local populations under French tutelage. As Mauss added in his prewar letters, “there is an abysmal difference between our negligence and the model organization of the Germans and Americans,”94 which could not be blamed on financial constraints, “as the Institutions created in Berlin are only those of Prussia, a country much smaller than France.”95

But in 1926, the situation had changed. The selection of the name “Ethnology” rather than “Anthropology” for Mauss’s new Institute was indicative of the division of labor between the two disciplines in the French metropolitan academic field at the time. For years, Mauss fought against the state funding of scientific chairs in raciology and somatology, which was the only chair created in France for anthropology before the creation of the Institute of Ethnology. Anthropology was less important to Mauss than ethnology, as the former was based on the observation of “racial traits that can endure a long time after a civilization has lost its mental, social and national singularity,”96 so its development, and particularly that of somatology, was not urgent. In contrast, cultural ethnography and museographic sciences were eminently pressing tasks for Mauss, as cultural practices and artifacts could disappear in one generation after the French occupation of new territories, which is why Mauss, Rivet, and others took to heart the mission to revive the Museum of Ethnology of the Trocadero at the same time as they created the Institute of Ethnology, as Alice Conklin and other historians have showed.97 At the same time, Mauss pushed for the creation of a French science of “ethnography,” which he defined “as the science which describes and classifies races, peoples, civilizations, or rather, that part of the science which focuses on the races, peoples and civilizations of an inferior rank, which differs from that other part called ‘history’ or ‘folklore,’ which describes the peoples of the East and of ancient Europe.”98

This last sentence should have any contemporary anthropologist who declares to be a Maussian think twice before taking at face value Mauss’s definition of the discipline. Of course, our Maussian colleagues in anthropology today do not think of themselves as being involved in the study of “the races, peoples and civilizations of an inferior rank,” and Mauss retains a definitive attraction among anthropologists because of his universal erudition and his attention to complex linguistic phenomena.99 But, for Mauss, the reasons for the development of “descriptive sociology” (or “ethnology”) in the colonies or in Algeria were not only scientific but also (and maybe more importantly for the minister) practical ones. Ethnology had practical implications for the art of colonial government that anthropology lacked: the measurement of crania may be of interest to racist criminologists interested in the science of eugenics but it does not tell you how to extract taxes from local populations without breaking implicit or secret sacred obligations for which tax collectors can be sanctioned by death. Mauss took considerable pains to convince the Ministry of the Colonies of the practical benefits that could derive from the development of ethnology in France.100 Even though, as Mauss wrote to the minister in 1913, “the utilitarian consequences” stemming from the creation of a “purely scientific Bureau or Institute of ethnology will be indirect, they will be considerable.”101 Indeed, as Mauss emphasized time and again in his memorandums on the topic, “nowhere is it truer that in colonial policy that ‘knowledge is power.’”102 As Mauss wrote:

it is of utmost political importance that we be informed of the state of mind of the millions and millions of Negroes whom we pretend to administer without knowing them, either in the Congo, Guinea, Sudan, Madagascar, as well as the salvage tribes of Annam, Laos and Tonkin, who are understood only by a few zealous military men, who nonetheless lack the time and resources to produce adequate descriptions of their mores.103

It was thus a major breakthrough for Mauss to obtain the creation of an Institute of Ethnology in Paris in 1926, and that the Institute of Ethnology later managed to obtain an important say on the knowledge deemed legitimate by the political and administrative authorities for the selection of future administrators in the French colonial field. At the Institute, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Mauss thus gave for instance a class titled “Ethnological Lessons for the Use of Colonial Administrators, Missionaries and Explorers,”104 and in 1927, Mauss even obtained the opportunity to teach a twenty-four-week class on ethnology at the Colonial School.105 Mauss’s multipositionality, and the interlocking of advisory boards in the various training centers of colonial administrators, certainly helped him build the legitimacy of the newly founded Institute of Ethnology in the eyes of the Ministry of the Colonies and the Colonial School. Even if ethnographic training at the Colonial School did not always translate into its use in the field,106 the role of ethnology in the curriculum of the Colonial School changed with the collaboration Georges Hardy started with Mauss and his Institute of Ethnology. Hardy greatly raised the prestige of his school by strengthening the academic content of its curriculum and by organizing preparatory classes in the “grands lycées,” which previously only trained students to the grandes écoles like the ENS and the École Polytechnique.107 Thus, entry into the Colonial School became a valued alternative for the smart young students who had failed the competitive exam for either of these alternatives, and who did not want to go in French law schools straight out of high schools. These smart students were likely to be attracted by Mauss’s charismatic erudition: at the Colonial School, thanks to the fact that Mauss himself, and later his most brilliant students (like Jacques Soustelle and Marcel Griaule) taught classes in ethnography, trainees could engage with the most interesting research in anthropology, sociology, and ethnography. Maussian ethnology had moved to the center of the orthodoxy in colonial sciences, along with French law and colonial economics.

As George Steinmetz writes, “the socio-spatial contours of imperial socio-scientific fields,” such as the one under study here “are shaped by the analytic object itself – by the empires being studied.”108 Thus, George Steinmetz’s reflections on the necessity for historical sociologists interested in the study of empires to not only contextualize the struggles of important thinkers in the metropolitan field of power, but also in the colonial fields, rings particularly pertinent, as the men and women who studied under Mauss’s supervision the past, present, and future of colonial relations in the French context not only drew upon the social capital they accumulated in the metropolis to move on with their career in the metropolitan field of power, but also on what Steinmetz has called “colonial capital”109 (a form of capital valued in the state structures outside the metropolis, whose certification was grounded on the demonstrated knowledge of the mores of colonial subjects) to ground the legitimacy of their claims to colonial administration.

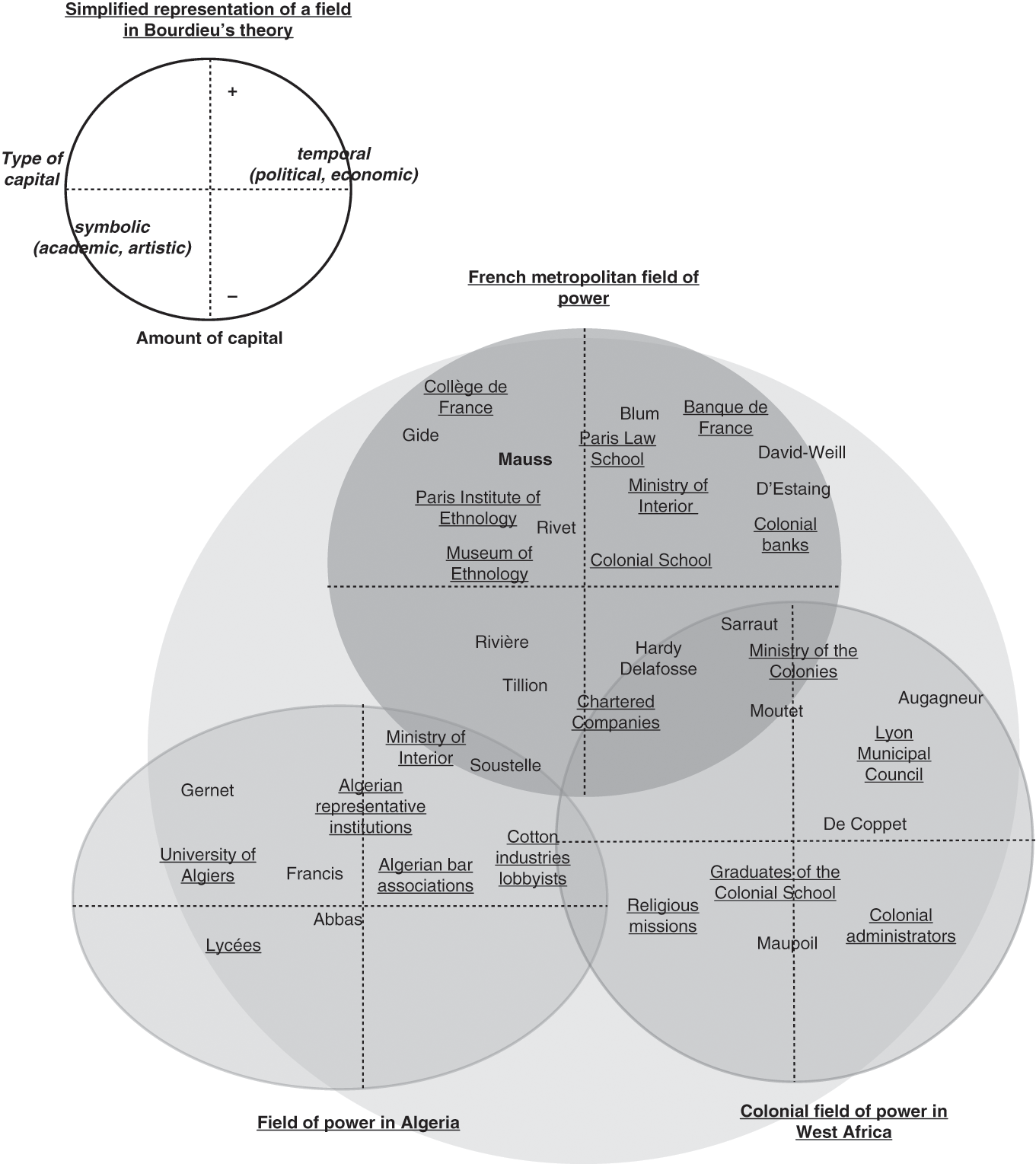

Rather than studying the circulation of social capital in one field only, we historical sociologists interested in the relation between the academic and political fields should then study the intersection between institutional logics in multiple fields: in the Algerian and West African colonial fields for instance (see Figure 2), various ministries (like the Ministry of Interior or the Ministry of Colonies), various private interests (like colonial banks and chartered companies that operated in the Congo for instance), as well as various institutions of higher learning (like the Colonial School or the Institute of Ethnology) had gained a stake in the colonial game, and the study of their interactions should be located in the specific fields in which these institutions operated.

As a result of such differentiation between various fields of power in the French colonial age, the “colonial capital” with which aspiring colonial administrators and anthropologists started their careers was spent with varying effects depending on whether they used it to fight ideological and administrative battles in the fields of power in the metropolis, in Algeria, or in the colonial field in West Africa, for instance. These men and women who circulated around Mauss not only institutionalized ethnology in the French metropolis, they also moved in an environment that is best described as a colonial field: it can neither be reduced to the purely French metropolitan field, nor to an international anonymous space. And this colonial field can in fact be subdivided in various sub-fields: the colonial field in West Africa, where careers of colonial administrators typically started at the Paris-based Colonial School, where Mauss started to teach ethnology in the late 1920s; and the Algerian field of power, where many more passageways existed with the metropolitan field, thus enabling an intense circulation between academic, political, economic, and administrative elites from the metropolis and Algeria. The Algerian field itself was not reducible to the other colonial fields, as its administrative elements fell under the authority of the Ministry of Interior and other Ministries in charge of deciding essential questions in the three Algerian departments that France claimed to belong to the French Republic itself. Representing where various institutions are situated in these various fields in the interwar period, Figure 2 can help sociologists and historians, although only schematically, highlight the existence of institutional forces beyond the immediate level of Mauss’s circle of interpersonal relations.

Rejecting the metropolis-centered view of fields is key to explain some critical discontinuities in the lives and careers of ethnologists who were trained by Mauss and carried on with his thoughts on gift exchange, as their lives moved beyond the colonial and metropolitan fields. In particular, George Steinmetz’s perspective of fields can help us explain why these intellectuals and administrators could accumulate high levels of social capital in the colonial fields – including Algeria, West Africa, East Africa and Madagascar, and Indochina – that could later be translated in the metropolitan field, at least during specific periods, and why their colonial capital suddenly became irrelevant after decolonization.

Here, the career of Jacques Soustelle not only illustrates how ethnographic knowledge was used to accumulate political and social capital in the colonial and metropolitan fields, but also why the sudden destruction of the colonial field after the Second World War so dramatically affected the life opportunities of these ethnologists/colonial administrators who drew on Mauss to think about international and colonial relations in terms of gift exchange. During the Second World War, it was first thanks to his connections from the ENS and the Musée de l’Homme and the ethnographic fieldwork that he had conducted in Mexico (whose indigenous populations from Yucatan Soustelle had long observed) that Jacques Soustelle “converted” his anthropological/academic capital into political cash: in 1939, when the war with Germany started, Soustelle was nominated in Mexico to become the head of propaganda services for the Central American region, a post he then used to raise funds for the Free France after General de Gaulle’s June 18 call.110 In 1942 Soustelle entered de Gaulle’s government in exile in London as Head of Information, before becoming the head of the intelligence service in November 1943, after the government moved from London to Algiers; then Minister of Information in May 1944, and Minister of the Colonies in November 1945. His career, judged from that point of view, was strongly embedded in the French metropolitan field of power, at least until he started accumulating, due to the specific circumstances of the Second World War, some capital in the Algerian field.

Soustelle’s political career extended far beyond the boundaries of the metropolitan state: for more than thirty years, he consistently transferred the academic capital he accumulated in the metropolitan field into political capital valued in the colonial and Algerian fields of power; and vice versa. For instance, when the Gaullists lost the 1946 elections, Soustelle convinced de Gaulle to form a broader trans-party movement (the Rassemblement du Peuple Français (RPF) in 1947), which he led as secretary general and director of the parliamentary group for the next eight years, until Pierre Mendès France named him governor general in Algeria in January 1955. Soustelle’s recognition as a skilled politician and an eminent anthropologist certainly intervened in Mendès France’s decision to appoint him as the highest civilian authority in Algeria, just two months after the beginning of the insurrection launched by the Algerian Front de libération nationale (FLN) on November 1, 1954.111 Then, Soustelle helped de Gaulle by fomenting a coup in Algiers in May 1958, which brought the Fourth Republic to its knees and de Gaulle back to power (and Soustelle back to the government as Minister of the Sahara and Atomic Energy).

But after de Gaulle dramatically shifted gears on the issue of Algerian independence, Soustelle left the government, and, after 1961, spent eight years in clandestine exile and permanent movement to hide from de Gaulle’s private intelligence officers-killers (the so-called barbouzes), as the war between Gaullists and pro-French Algeria supporters raged within the French intelligence circles – until the events of May 1968 diminished the authority of de Gaulle. Back from his exile in 1968, Soustelle could still count on the active support of Parisian academics, like Claude Lévi-Strauss, to land a job back in academia and at the French Academy,112 but he was no longer able to influence either national or international politics.

4 The Competition between Disciplines in the Colonial Fields of Power

By situating the development of anthropology and international law in relation to both the French colonial fields of power and the metropolitan field of power, the next chapters will explain how anthropologists, who specialized in knowing the mores of the colonial subjects whose lives their state or concessionary companies administered, used their specific knowledge and their accumulated colonial capital to push for specific arrangements between the metropolis and its overseas territories, sometimes in alliance with, at other times in opposition to, other professionals such as jurists (specialists of international and/or colonial law), economists (specialists of colonial trade and finance) and the bureaucrats and policymakers involved in colonial affairs.113 Indeed, the colonial fields in which Maussian ethnologists gained a stake were not empty, but already populated by different experts, who fiercely defended their jurisdiction over colonial policy. Once they gained entry into the colonial fields, ethnologists needed to form alliances not only with colonial administrators who were politically close to them, like Léon Blum, or his Minister Marius Moutet, or some governor generals like Marcel de Coppet, but also with other experts coming from other disciplines like international law, colonial law, or public finance.

The notion of a colonial field is thus helpful to situate the space in which these debates and conflicts between disciplines took place, for instance, between ethnologists and economists as well as high civil servants in charge of the colonial trade policy, like Edmond Giscard d’Estaing (1894–1982) who had long opposed the socialist views defended by Léon Blum or Maurice Viollette on the necessity for France to engage a “generous” colonial policy based on gift exchange between the metropolis and its overseas territories.114 Men like Edmond Giscard d’Estaing had very different trajectories from Mauss’s students: for instance, he was an inspector of finance who was the High Commissioner of the Rhineland under French occupation during the early 1920s before becoming the administrator of French banks in Indochina, and then the father of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (1926–), who preceded François Mitterrand (1916–96) as President of the French Republic. His views on colonial trade were quite typical of the opinions and expertise found in the French Treasury.115 Edmond Giscard d’Estaing often found himself arguing against the logic of the gift exchange and the integration of colonial subjects (Algerian subjects in particular) in the body politic of the French Republic, which was defended by some of Mauss’s students, like Jacques Soustelle. For Giscard father, if the metropolis wanted to be generous, it had to find the best investment opportunities for its capital rather than prioritize sending it to Algeria, where investments could be wasted.

When they intervened in the debates on colonial policy, high civil servants who had a training in finance, like François Bloch Lainé (1912–2002), an economist who became France’s Treasury Director in 1947, and whose great uncle was none other than Léon Blum, did not look at the ethnographic facts collected by ethnologists or colonial administrators, but at instruments of macroeconomic policy, such as France’s balance of payments. On this basis, they often came in direct conflict with Mauss’s students, as they argued that the logic of continued gift exchange between the metropolis and its colonies turned “the logic of the Colonial Pact upside down” as “France provided the metropolitan francs which allowed its colonies to keep a dramatically unbalanced balance of payments,”116 as a result of their imports of industrial goods produced in the French metropolis. To understand the shifting meanings of the notion of gift exchange, it is thus essential to contextualize the debates in which ethnology positioned itself in the range of disciplines that claimed a stake in the colonial field.

In the interwar period, ethnologists not only had to defend their legitimacy against economists and trade specialists, but also against international law scholars, some of whom were sympathetic to the Durkheimian ethnologists gathered around Mauss, while others paid little attention to the local legal contexts in which the French state imposed its legal norms and rules when it expanded its influence to Algeria or West Africa. As Martti Koskenniemi demonstrates, after the Great War, some international law scholars had been influenced by the Durkheimian sociological approach, like Georges Scelle (1878–1951),117 who was a collaborator of L’Année sociologique, and who taught both at the University of Paris and the Institut des Hautes Etudes Internationales, an institute founded in Geneva with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation118 to serve as an observatory for the study of the emerging world society – now the Graduate Institute, where I happen to find myself teaching and writing. Confident in the ability of the League of Nations to generate international solidarity through cultural, legal, and economic exchanges, Scelle taught that political–legal ties of a quasi-federal nature would almost naturally emerge among member states of the League of Nations if exchanges between a plurality of political societies proliferated – in ways that were reminiscent of the Maussian notion that political societies moved up the scale of integration as they practiced gift exchanges, as I will show later. Like Mauss’s students at the Institute of Ethnology, Durkheimian international law scholars did not oppose colonialism: they found in the League of Nations, and the mandates it granted to the French and British Empires in Africa and beyond, an opportunity to bring diverse political societies toward higher levels of civilization, so as to foster world peace and international solidarity.119

In contrast, the ethnological lessons that Mauss and his students could draw on gift exchanges by studying the interactions between legal norms in the colonial context, were much less appreciated, if recognized as legitimate at all, by international law scholars who worked in the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs before the Second World War. For many of those jurisconsults, international law was merely an instrument to be used in the service of European great powers: for them, paying attention to the legal norms recognized by colonial subjects amounted almost to an unpatriotic gesture aimed at hurting the absolute rights of the colonial power.120 For instance, Jules Basdevant (1877–1968), a professor of international public law at the University of Paris and Sciences-Po Paris, who worked for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a jurisconsult in the 1930s – a position he quit in 1940 when Pétain came to power – and a member of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) from 1946 to 1964, was quite typical of this generation of jurisconsults.121 Like Albert de la Pradelle (1871–1955), who taught at the University of Grenoble, before founding the Paris-based Institut des Hautes Etudes Internationales, and many other jurisconsults, Basdevant “made no secret of his distaste of the solidarists’ sweeping generalizations”122 about history’s progress toward a more integrated international society, and their unlimited hope in the power of economic interdependence to generate new quasi-constitutional legal norms between a plurality of political communities. In his work as jurisconsult, Basdevant was not only ardently in favor of France’s colonial mission, but he was also particularly oblivious of the legal and contractual obligations that colonial subjects had recognized (and had been recognized) as theirs: for instance, from 1918 to 1920, when he was charged with the official task of publishing the French Record of treaties and conventions, he excluded most of the treaties signed by the French state with African and Asian sovereigns (with the exception of those signed with Ethiopia and Liberia), even those signed by the representatives of the Third Republic with the Algerian emirs (like Abd El-Kader), Nigerian kings (like Samori Touré, the grandfather of Seku Touré, the first president of independent Guinea) or East Asian emperors, which had been ratified and even published in the Journal Officiel.123 Basdevant’s symbolic act of exclusion perfectly reflected the colonial mindset of some French jurists, for whom the only purpose of these conventions had been to secure the nonintervention of other European great powers when the French Republic claimed African territories as its own.124

To understand the reception of Mauss’s ideas in the colonial field, it is thus necessary to reconstruct the logics of these various fields during the times when Mauss was writing and publishing. Furthermore, if one wants to understand how the reception of his ideas on gift exchange evolved over time, it is important to describe the mechanisms of intergenerational struggle that worked these fields from within. Indeed, from the interwar period to the postwar era, these fields experienced dramatic changes. For instance, after the Second World War, the emergence of strong law schools outside Paris, in which new disciplines like political science, geography, or Weberian political sociology were combined with international law, changed how international law was being taught, and challenged the association between the study of international law and the defense of French colonialism. In this approach to international law, there was little use for the lessons that ethnologists could draw from their study of legal customs, but rather, the emphasis was placed on understanding the relations between legal rules, the life of domestic and international bureaucracies, and the agendas of political parties that pushed for the reform or conservation of existing legal rules.

The strength of this new approach to international law was evident for instance in the Law School of the University of Grenoble, in which Claude-Albert Colliard (1913–90) served as dean for a long time, and where Mohammed Bedjaoui came to study until he graduated in 1956, with a doctorate in international law. Colliard was, in the words of Bedjaoui, the “perfect example of the radical socialists of the Third Republic, who hated colonialism”125 – a subject he also taught at Sciences-Po Grenoble, from which Bedjaoui also graduated, and where he took Colliard’s course “Imperialism and the Economy.”126 In his realist approach to international law, ethnology, and the ethnographic study of cultural, social and economic exchanges between political societies, had no place – but this no longer meant that those who sponsored this approach adhered to a pro-colonial ideology, in contrast to interwar international law scholars like Jules Basdevant. Affirming the exclusive rights of states to author international law (against the pluralist Durkheimian precepts found in the study of law as practiced in the colonial field) stood in harmony with the goal of achieving recognition of statehood for independent colonies,127 and thus, with the study of the administrative and legal criteria that international legal scholars had so far used to define statehood. In this new postwar academic context, ethnology in general, and the ethnography of gift exchange, had to change to remain relevant to the political debates of the time and the pressing question of colonial reform.

5 The Imperial Invention of “Third World” Intellectuals

At last, this book hopes to convince sociologists and historians to adopt the neo-Bourdieuan view of fields in order to explain continuities that were masked by the sudden process of decolonization for the former colonial subjects: for instance, the French (second-class) citizens from the colonies (or Algeria) who experienced high social mobility in the French academic or colonial fields before decolonization, and who remained in positions that straddled two fields of power after national independence – both in the former metropolis, where they kept many ties, and in their newly independent states, where they often rose to the top tiers of power. For instance, the intellectual trajectory of Bedjaoui and those of his mentors Ferhat Abbas (1899–1985) and Ahmed Francis (1912–68) – a doctor who had studied medicine in Paris (obtaining a doctoral degree in 1939) and who had practiced in Setif, like Abbas – were deeply rooted within the French fields of international public law and colonial policy.

In other histories of international law in which such intellectuals figure prominently, such as in Balakrishnan Rajagopal’s International Law from Below,128 there is a tendency to treat such intellectual and political elites from “the Global South” as “Third World” elites, as if their trajectory was tied only to their newly independent nation-state and to the Third World more generally. Doing so may lead historians of international law to ignore the processes of capital transmission and accumulation that had started in the French metropolitan field of law before the beginning of national independence.

The historiography on the New International Economic Order (NIEO) provides a good example of how historians can forget that key notions associated with this broad program found their historical and intellectual origins in the French academic fields. After Algerian independence, the mid 1970s were an intense period of Algerian diplomatic activity, which in turn explains why no international lawyer from the Third World exercised a similar influence and role as Mohammed Bedjaoui on the definition of the NIEO program.129 For twenty years, and until hopes to reform the economic international system waned after Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister in the United Kingdom and Ronald Reagan President of the United States, Mohammed Bedjaoui indeed played a leading role in formulating the legal doctrine behind the economic program of the NIEO.130 As Special Rapporteur to the International Law Commission (ILC) he steered the work of eminent legal scholars who, through their participation in the ILC, reported to the UN General Assembly on points of law for which the General Assembly had sought clarification.131 For this reason, the publication of his acclaimed book Towards a New International Economic Order, published in 1978 by UNESCO,132 was not only the work of a learned scholar of international public law but also the platform on which a “Third World Lawyer tried to structure the struggle of the Group of 77,”133 as Balakrishnan Rajagopal writes.

But, in fact, Bedjaoui’s reach extended beyond the confines of international organizations and reached far into the Franco-Algerian bilateral relation: after serving as Algeria’s Minister of Justice until the late 1960s, he became the Algerian Ambassador to France (1970–9) when the nationalization of French oil interests in Algeria was undertaken, before he moved on to other prestigious postings, first as Ambassador to the UN in New York (1979–82), and then Judge at the ICJ for almost twenty years. Furthermore, it is impossible to understand his career and his intellectual trajectory without placing them in the history of the French metropolitan and colonial fields of law before and after Algeria’s independence. Indeed, the few Algerian lawyers and legal scholars who, like Bedjaoui, used their legal status, expertise, and skills to defend Algerian independence after the Second World War were all trained in the metropolis, and evolved in the metropolitan field of law, whether they were of European, Arab, or Caribbean descent.