Book contents

- Women, Crime and Punishment in Ireland

- Women, Crime and Punishment in Ireland

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures, Maps and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: ‘Another generation of jail-birds’

- Case Study 1 ‘The terrible temptation’

- Case Study 2 ‘A gang of coiners’

- Case Study 3 ‘The workhouse girls’

- Case Study 4 ‘A person of very superior attainments’

- Case Study 5 ‘A most remote part of the country’

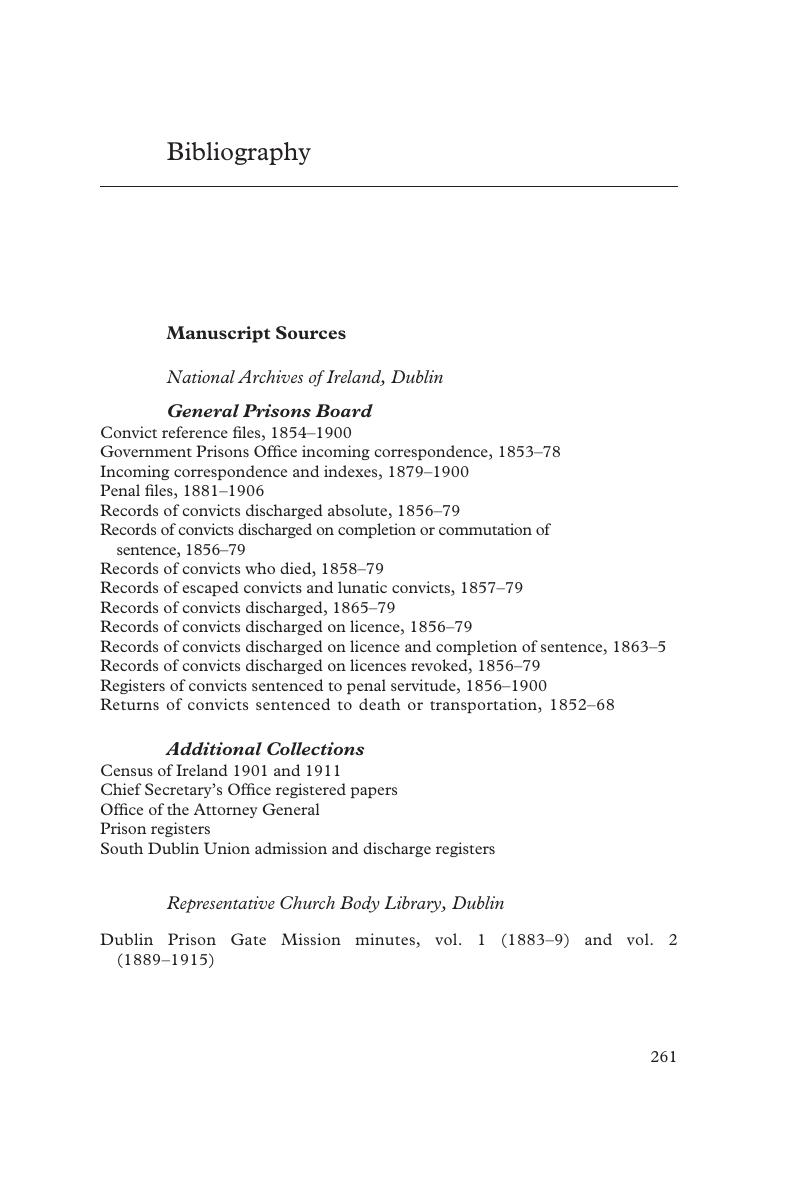

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 September 2020

- Women, Crime and Punishment in Ireland

- Women, Crime and Punishment in Ireland

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures, Maps and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: ‘Another generation of jail-birds’

- Case Study 1 ‘The terrible temptation’

- Case Study 2 ‘A gang of coiners’

- Case Study 3 ‘The workhouse girls’

- Case Study 4 ‘A person of very superior attainments’

- Case Study 5 ‘A most remote part of the country’

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Women, Crime and Punishment in IrelandLife in the Nineteenth-Century Convict Prison, pp. 261 - 286Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020