If Tanagras project an ideal of a mature woman, that woman is certainly not old. But this is not to say that old age is excluded from visual imagery in the Greek and Roman worlds; and Hellenistic art, in particular, develops a form of realism that includes studies of the ageing body. As with Tanagras themselves, such imagery finds expression less in the mythological world of gods and heroes than in genre subjects of everyday life: a trend that begins to be fully evident in Alexandria (in poetry as in art) in the third century BC.Footnote 1

But why would a woman’s ageing body be depicted at all? Smith credits such images with a votive function, citing the sanctuary of Asclepius, as described in Herodas’ Fourth Mime, as evidence of an eclectic approach to temple dedications.Footnote 2 Among the sculptures on display in Herodas’ temple, visitors see an image of Hygieia (‘Health’), along with a girl looking up at an apple, an old man, a boy strangling a goose (this last, familiar from the repertoire of Roman copies that now survive) and a local woman, so realistically portrayed that ‘looking at this likeness, no-one would need the real thing’.Footnote 3 What were such likenesses and accompanying genre pieces for?

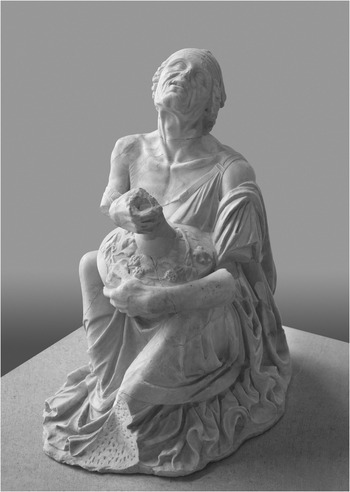

Belonging as she does to a category of realistic depictions that includes socially disadvantaged figures of peasants and fishermen,Footnote 4 our old woman’s original purpose – and her provenance, too – remain unclear. Two Roman versions of the statue exist, one in the Capitoline Museum, Rome, and another, illustrated here (Figure 9a), in Munich. Hugging an ivy-decorated wine jar, seated on the ground, the woman is evidently intoxicated. She sways; her wrinkled face is raised; her open mouth reveals missing teeth (Figure 9b). Her drapery slips from her body to expose bony shoulders and sagging breasts. The figure of a drunken old woman (anus ebria) by the celebrated sculptor Myron is mentioned by Pliny,Footnote 5 but there is no secure connection between that statue and the Capitoline or Munich sculptures. Sande suggests that she belongs to a Roman rather than a Greek tradition,Footnote 6 and Ridgway proposes that the drunken old woman statue type might be Augustan.Footnote 7 Conversely, Pfisterer-Haas and Wrede identify the statue as Hellenistic Greek on the strength of an old-woman motif on the vases, terracottas and grave reliefs of Classical Greek art.Footnote 8 Pollitt and Smith place the sculpture in the Hellenistic period,Footnote 9 and today most scholars at least agree that its original belongs to the third or second century BC.

If there is now a scholarly consensus regarding the old woman’s date, her function still remains elusive. Was she perhaps a private sculpture? Beard and Henderson suggest that she might have been produced for a private commission, but wonder why a member of the Hellenistic elite would want to adorn their palace or villa with such an ‘unlovely specimen’.Footnote 10 For them her meaning resides in a comic reflection on the nature of feminine beauty and desirability. Certainly, the old woman might be a humorous creation, but a more plausible reading, I suggest, involves, not a negative slur on female ageing, but a Bakhtinian celebration of the non-idealized body.

Mikhail Bakhtin famously located the carnivalesque in various periods and genres of the Western world, including the ‘serio-comic’ literature of antiquity, from the Socratic dialogue to the Menippean satire,Footnote 11 as well as such ‘novels’ as The Golden Ass and the Satyricon;Footnote 12 and the Bakhtinian ‘carnival’ has been variously incorporated into the study of classical literature more generally.Footnote 13 But of particular relevance to an understanding of Greek sculpture is Bakhtin’s concept of ‘embodiment’, central to his presentation of the carnivalesque, whereby ‘festive laughter’ is associated with the intentional subverting of ideal body categories and conventions (and thus with the most unglamorous bodily functions), along with the body’s gender, status and age. In Rabelais and His World, Bakhtin does indeed look to Roman terracotta statuettes of old women laughing in (as he argues) the jubilant and unruly spirit of carnival,Footnote 14 and it is his interpretation of these terracottas of the ageing female body that promises to illuminate our statue.

The age of the woman in our sculpture distinguishes her from all the other objects discussed so far in this book. Classical bodies are mostly idealized and ageless, but, by the fourth century BC, artists had begun to experiment more fully with depictions of the older male body in free-standing honorific portraits and funerary relief sculptures. Old men are distinguishable from their younger mature counterparts by their receding hairlines, long beards and physiognomic details of furrows, crow’s feet, hollow cheeks, frown lines and naso-labial folds.Footnote 15 Philosopher portraits, in particular, project a new type of masculinity that celebrates the mind rather than the body. Old age is signified by posture (stooping shoulders and sagging chest), as well as head and face (age lines and sombre expression), in honour of venerable aged men.

There is no female equivalent to the philosopher type, nor do women’s portraits in general include the physiognomic variety of their male counterparts. For women, beauty is ‘the primary signifier’,Footnote 16 and women’s portraits remain generalized, youthful and idealized until the late Hellenistic period, when signs of age and individuality begin to emerge under the influence of the Roman veristic style.Footnote 17 Visualizations of older women do occur in Archaic and Classical vase paintings in representations of mythological narratives: Pfisterer-Haas identifies Geropso (Heracles’ nurse), Aithra (Theseus’ mother), Eurycleia (Odysseus’ nurse) and Phaia (keeper of the Crommynian sow that Theseus will slay) as recurrent figures.Footnote 18 But the old woman only materializes as large-scale sculpture in genre subjects of the Hellenistic period. A male counterpart is the old fisherman, known through Roman copies. A notable black marble example in the Louvre (formerly known as the Dying Seneca) shows a careworn and weather-beaten face, a painfully thin torso, and sinewy arms and dilated veins.Footnote 19 Wearing only a loincloth and shown wading in shallow water, he is presumably casting nets, still working even in a decrepit old age. The drunken old woman is often paired with the old fisherman. But in her the realism of age is not complete: her forehead remains remarkably smooth and her eyebrows arched,Footnote 20 even though crow’s feet are prominent around her eyes, and the rest of the face, below, crumples with the deep creases of old age.

Although the identity and occupation of the fisherman is straightforward, the old woman’s is more difficult to gauge. Pollitt gives her a Dionysiac attribution, connecting her directly with Alexandrian festivals by identifying the ivy-decorated wine jar that she clutches as a lagunos used in the Lagunophoria, a rustic drinking festival in honour of the Bacchic god.Footnote 21 Ridgway rejects this association and sees the vessel as a less specific wine jar,Footnote 22 but in two comparable statues a festival connection is likely. Another old woman type is illustrated in a standing statue in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; she carries a basket of chickens and fruit and wears a garland of ivy leaves, as if on her way to sell her goods or offer them to the gods at a religious festival. A fisherman type also exists in New York (with a more complete version in the Conservatori Museum, Rome); he holds a basket of fish in one hand and wears a long cloak unsuited to work, suggesting that (like the standing old woman) he may be on his way to market or to a festival. The drunken old woman might well be offering her wine at a Dionysiac festival, and all three figures could plausibly be credited with a meta-votive function as ritual offerings that themselves show dedicants making offerings at a communal religious event.Footnote 23

Although the fishermen are seen as poor men trying to eke out a living while they still have the strength, the women are far from destitute: they wear fine garments and sport elaborate hairstyles and finger rings. A seated position, like our old woman’s on the ground, is characteristic of beggars and suppliants,Footnote 24 but any such identity is precluded by her appearance. She is wearing earrings and has two rings on her left hand; her dress is elegantly hemmed; and a head cloth protects her neat coiffure.Footnote 25 Might she be an old prostitute, still flaunting her finery and clutching a phallic wine jar as a reminder of her past occupation?Footnote 26 An argument in favour of that interpretation is the literary precedent of the courtesan’s fear of old age, a familiar trope in Latin love elegy and its Greek precursors.Footnote 27 At the same time, it is the woman’s dishabille that encourages this line of thought. An off-the-shoulder effect had been used in earlier sculpture to signal sexual availability (‘Aphrodite’ from the East Pediment of the Parthenon), though it could also mean vulnerability (Lapith women from the West Pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia) or indeed female otherness (Wounded Amazon). In this woman it might be interpreted in terms of comic eroticization and disregard for female propriety: Beard and Henderson propose that she is actually a witty parody of the Aphrodite of Cnidos, ‘now long past her prime and collapsed over a version of the vessel (here a wine jar) that used to stand at her feet’.Footnote 28 But, if so, is she merely a figure of fun, or does the incongruity of bare flesh and ageing body have a deeper significance? Perhaps this old woman’s disregard for personal modesty, combined with her inebriation, suggests not the helplessness of an old lush but a bold disregard for social and sexual convention.

Despite increasing academic attention to body studies in recent years, the ageing body, and the ageing female body in particular, remains marginalized. Woodward has analysed the absence of old women from today’s popular culture and notes that ‘with the exception of disability studies and work on illness narratives, our implicit and unexamined assumption when we make reference to the [female] body as a category of cultural criticism is that the body is a youthful, healthy body’.Footnote 29 She goes on to examine the work of the few contemporary artists who have re-inserted the ageing female body into contemporary visual culture. One example is Canadian photographer Donigan Cumming: his photographs of seventy-six-year-old Nettie Harris, entitled Pretty Ribbons, confront the viewer with images of Harris undressed.Footnote 30 There is a recognizable affinity between the Hellenistic drunken old woman and Cumming’s photograph of Nettie Harris sleeping (Nettie Harris, July 7, 1989), glass in hand and fur wrap exposing a naked breast. In both images, the display of the female body – drunk, exposed, old – challenges the viewer to reconsider relationships between age and gender. A few other contemporary artists have drawn attention to the invisibility of older women in today’s visual culture by reintroducing the ageing female nude as a subject for art. In Ella Dreyfus’s photographic exhibition, Age and Consent (1999), close-to-life-size nudes challenge the negativity associated with the perceived loss of beauty and desirability.Footnote 31 More recently, and in a different artistic sphere, Mexican performance artist Rocío Boliver has staged ‘Between Menopause and Old Age’ (2012), tackling sexism and ageism through a subversive mockery of media-driven anti-ageing agendas.

If old women are marginalized in contemporary Western culture, this was doubly so in patriarchal ancient Greece. In Greek literature, old age is often represented as negative, and Bremmer and Falkner paint an uncompromising picture of post-menopausal women, who, if referred to at all, are subject to derision and abuse.Footnote 32 However, Henderson’s analyses of relevant aspects of fifth-century Attic comedy have uncovered a more complex characterization: the old woman is a significant character in a number of plays and the main character in two lost comedies, Pherecrates’ Old Women and Aristophanes’ Old Age.Footnote 33 In these examples, negative stereotypes of the argumentative and troublesome old crone co-exist with images of women upon whom age has conferred authority.Footnote 34 In Greek tragedy, too, the nurse figure, in particular, emerges as an intelligent and authoritative older woman.Footnote 35 And the real old women of ancient Greece no doubt took on a variety of roles, including social functions centred around religious, domestic and pedagogical work.Footnote 36

That said, Bremmer and Falkner’s negative stereotypes are not unfounded, and old women are the target of a particular type of misogynistic invective in textual sources from Archilochus to the Greek Anthology, where comic portrayals of an old woman centre on her sexual appetite but her lack of sexual charm.Footnote 37 In Aristophanes’ Plutus, a rich old widow rejected by her gigolo is the object of ridicule and her ageing body the target for abusive insults.Footnote 38 Similarly, at the end of the Ecclesiazusae, three old women – each older and uglier than the last – compete with one another over their legal right to sleep with a hapless young man.Footnote 39 Epigrams in the Greek Anthology contrast former beauty with present decay, focusing on wrinkled faces that were once flawless, and grey hair that was once natural, disguised with dye or a wig.Footnote 40

Drunkenness is another negative stereotype applied to the older woman, reflecting the fact (or prejudice) that widows in particular (lacking the control of a husband) had no restraints on their access to wine.Footnote 41 According to an allusive claim in Aristophanes’ Clouds,Footnote 42 the stereotypical old woman – coarse and drunk – figured prominently in Eupolis’ Maricas (performed at the 421 BC Lenaea), where the demagogue Hyperbolus’ mother is ‘an old crone’ who drunkenly dances the kordax.Footnote 43 By the time of Aristophanes’ Ecclesiazusae (c. 392 BC), a liking for unmixed wine is one of the comic stereotypes of female behaviour,Footnote 44 and, much later, a poem in the Greek Anthology even describes an old woman whose drunken behaviour gets her drowned in a wine vat.Footnote 45 The same stereotyping is found in visual sources. An Attic red-figure skyphos (c. 470–460 BC: Getty Villa, Malibu) depicts a woman secretly drinking wine while transporting it from a storeroom. One side of the vase shows a storeroom filled with wine paraphernalia and the other a woman hurriedly drinking from a huge skyphos. Behind her a slave girl carries a wineskin, suggesting that the wine is unmixed. The drinking woman herself wears a long dress and neat coiffure, indicating that this may well be a wife whose only opportunity to drink is to do so on the sly.Footnote 46 Although not old, this woman is far from the feminine ideal often depicted on vases: she has a double chin, accentuated by her gulping motion.

While excessive drinking in women was habitually censured as a weakness, opportunities to participate in the drinking culture were abundant for women taking part in symposia, wedding celebrations, public festivals and private rituals,Footnote 47 and the drunkenness of the old-woman statue may seem more appropriate if her context is indeed a Dionysiac festival. But in any case, this woman’s inebriation seems at odds with her seemingly high status, perhaps in the comic tradition of the drunken Heracles type known from Roman statuettes, where heroic reputation is undercut by drunken incapacity.Footnote 48 And it does seem a likely conclusion that, like the Roman Hercules statuette, the drunken old woman is a comic creation. She elicits an ambivalent response from today’s viewers, who often imbue her with a pathos probably unintended by her creator. Zanker, for instance, connects her with Callimachus’ ‘Hecale’, the poor old woman who generates an emotional bond with the reader when she recounts the sorry story of her life.Footnote 49 Conversely, Smith cautions against reading this sculpture from a modern perspective: rather than a pitiable creature, she is ‘a laughing figure, in the care of the wine god. She bares her teeth like trouble-free satyrs and maenads: she is hilara – merry or exhilarated.’Footnote 50 Masséglia too sees the woman as either laughing or singing,Footnote 51 perhaps in a ritual context; Wrede suggests that the comic aspects of Dionysiac worship are directly relevant to the woman’s merry attitude;Footnote 52 and O’Higgins connects ritual and humour most comprehensively, proposing that laughter was a central aspect of female religious behaviour in which women exchanged verbal jokes within the rituals of Demeter and, indeed, Dionysus.Footnote 53

Women predominated in the cult of Dionysus, where traditional behaviours of domestic work and child-rearing were abandoned,Footnote 54 at least temporarily. In the Greek imaginary, the most respectable wife and mother could be transformed through Dionysiac ecstasy into a frenzied maenad: witness Pentheus’ mother Agave, who, in Euripides’ Bacchae, even participates in the dismemberment of her own son. Within more ordinary experience, though, drinking wine was central to Dionysiac rituals and must in itself have facilitated a lack of inhibition and a flouting of everyday rules of behaviour. Csapo describes the worship of Dionysus as involving ‘liminal rituals’ which transgressed class boundaries and other social hierarchies.Footnote 55 And it is just such a subversion of social norms within a collective celebratory environment that recalls the Bakhtinian concept of the carnivalesque.

In his quest to come to terms with the literary form of the novel and, in particular, its parodic and comic aspects, Bakhtin looks to the meaning of laughter in folkloric culture. In his introduction to Rabelais and His World, he identifies carnival folk culture in early modern society with ritual spectacle, comic verbal composition and marketplace oaths, curses and speeches, all of which he sees as embodying a spirit of openness and positive mockery. At its broadest, the Bakhtinian carnivalesque characterizes a worldview embracing festive laughter that is both subversive and liberating. A deliberate flouting of the conventional norms of status, age and gender undermines authority and seems to promise alternative modes of being. Embodiment is at the heart of carnivalesque meaning, and his emphasis on the human body makes Bakhtin’s ideas especially pertinent to a reading of the sculptural form. Understandings of human corporeality are central to Rabelais and His World, which proposes a distinctive reading of Gargantua and Pantagruel by the sixteenth-century French writer François Rabelais. In this comic novel that subverts the assumptions of dominant forms and styles through exuberant humour and celebratory chaos, corporeality belongs, not least, to ‘the grotesque body’. Rabelais’s writing emphasizes excess and the ‘lower bodily stratum’Footnote 56 of consumption, excretion and sex. For Bakhtin, emphasis on the body’s material dimension affirms the recurrent patterns of human life that belie social difference. The grotesque body, like the spirit of carnival, rebels against the conventional constraints of authority. ‘The primary reflex’ of Bakhtin’s grotesque body, ‘when it is not defecating or ingesting, is to laugh’.Footnote 57 And this laughter is never negative or judgmental but all-embracing and liberating. Indeed, in upturning hierarchies, mocking control and inverting norms, festive laughter ‘demolishes fear and piety’.Footnote 58 If the Bakhtinian carnivalesque is applied to a reading of our drunken old woman, then, she becomes, not a figure who is tentatively approached with apprehension or pity, but one who reaches out to embrace her viewers in a spirit of universal celebration.

Although not always directly associable with Bakhtin’s essentially literary category of the grotesque body, Greek terracottas, bronzes and vases likewise show ‘a chaotic farrago’Footnote 59 of all forms of physical and psychological otherness in opposition to modest and restrained idealism. Mostly represented in small scale, studies of individuals with disabilities and deformities make up a category that intersects with Hellenistic realism and has been labelled ‘grotesque’. As an art-historical term, ‘grotesque’ was first applied to the fantastical hybrid figures of Roman wall painting when rediscovered during the Renaissance, but it now refers to an indeterminate category at any site where ‘disgust mixes with laughter’.Footnote 60 Ancient grotesques might be derived from comic performance, whose masks, costumes and padding created caricatures that exaggerated physical appearance,Footnote 61 or equally from pre-dramatic performances that paraded physical otherness.Footnote 62 In either case, in performance as in visual art, the grotesque body is configured in terms of a broadly based humour that transgresses norms of representation.

Along with its seeming comic connotations, grotesque imagery also had a ritualistic function in Greece and Rome. Himmelmann has explored the archaeological context of grotesque figures in sanctuaries and burial sites and stresses their links with myth, ritual and religion.Footnote 63 Mitchell understands grotesque imagery as having apotropaic powers, noting the predominance of red paint (a colour associated with apotropaism) on grotesque terracottas.Footnote 64 A red-figure skyphos in Munich’s Antikensammlungen depicts a naked female dwarf, garlanded and drinking from a wine cup.Footnote 65 Dwarfs are usually depicted as male, but this woman’s gender and her nudity most probably have a ritual meaning. The reverse of the skyphos depicts a giant phallus with offerings of basket and wine cup, suggesting that both scenes are connected with the Eleusinian Haloa, a fertility festival dedicated to Demeter and Dionysus, in which female rites included the carrying of a giant phallus. The short, round body of the female dwarf would seem to be a caricature,Footnote 66 combining humour with ritual.

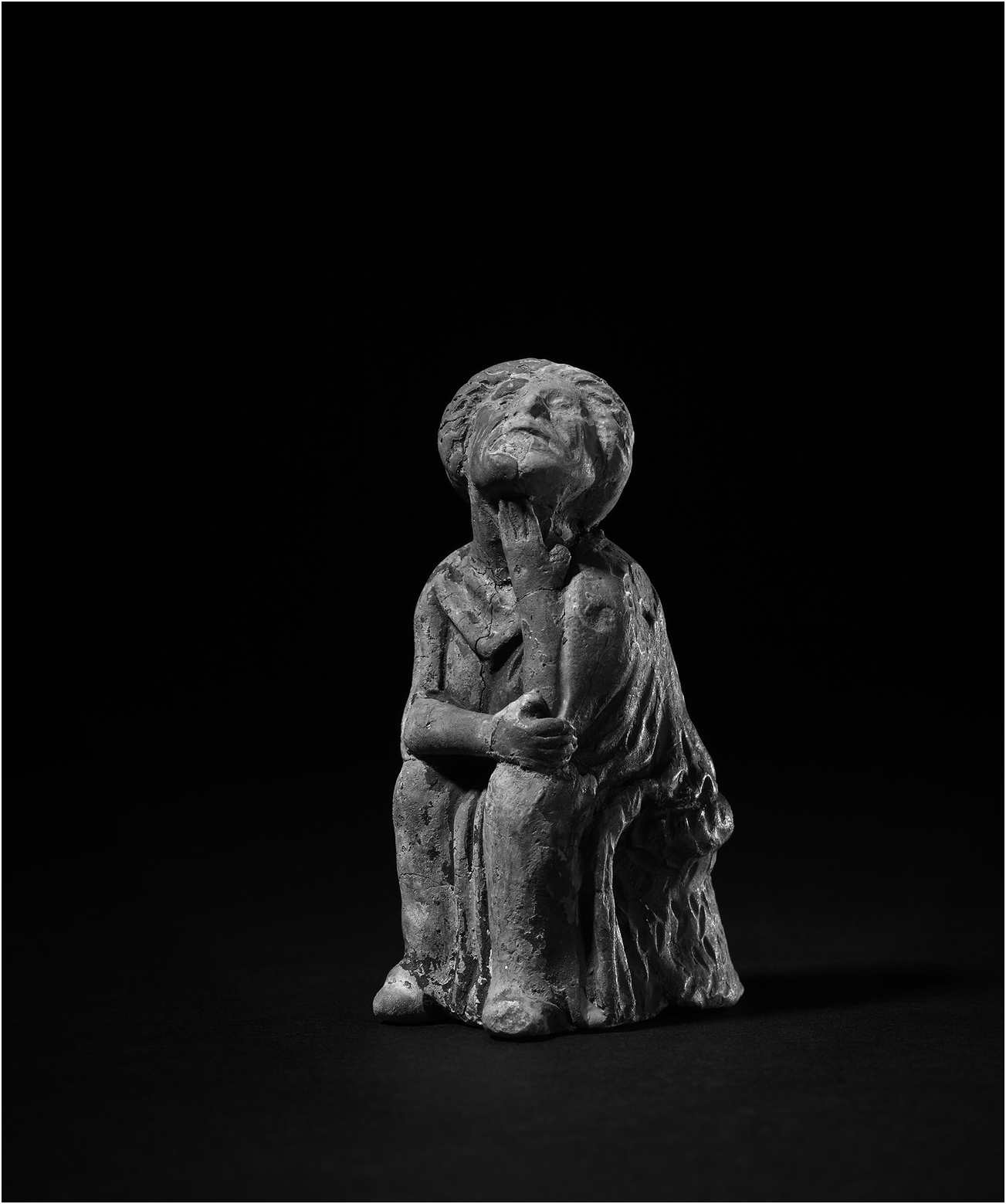

Alongside dwarfs and hunchbacks, old women are among the most common type of grotesque statuettes. Pfisterer-Haas identifies a cultic connection in certain representations of these women with baskets or piglets, or else shown naked and squatting.Footnote 67 But other terracottas too might be ritual objects – for example, statuettes showing drunken old women clutching wine jars much in the vein of our statue.Footnote 68 One related type of grotesque involves terracottas of naked old women with protruding bellies and sagging breasts, which are often thought to be caricatures deriving from comic performance in the form of a stock character of the ageing hetaira.Footnote 69 Yet these too might be open to cultic interpretation.Footnote 70 A Hellenistic terracotta statuette in the British Museum (Figure 10) is often identified as a comic actor in role. It shows a seated old woman lifting her face upwards with her hand supporting her chin. She is draped, but her arms are bare, and the folds of drapery clearly show the outline of parted legs and breasts. Her seated position, bare arms, upraised head, wrinkled face and grimacing mouth, all recall our drunken old woman. Another comparable terracotta is a naked torso in the Louvre of an elderly woman with concave chest and sagging breasts and stomach.Footnote 71 Sitting with her legs apart, she has her genitals exposed and her vulva clearly delineated, recalling imagery connected with Baubo.Footnote 72 Her posture indicates an apotropaic meaning for herself, for other old women grotesque statuettes and perhaps for large-scale statuary like the Munich old woman, too.

Modern critics emphasize the unstable nature of the grotesque: it is undetermined, changeable and boundless.Footnote 73 In representations of the female body, in particular, its open and evolving nature is at odds with the containment of the ideal nude in which the body is a closed and impenetrable image. The terracotta torso in the Louvre opens her legs to show vulva and vagina; she is not the sealed and impenetrable body so often associated with the female nude. As we have seen, terracottas of the old woman Baubo show her revealing her genitals to the grieving Demeter, provoking apotropaic laughter.Footnote 74 Russo’s study of the grotesque in Western art sees the female grotesque as transgressive: it subverts the male gaze and the traditional power dynamics of representation.Footnote 75 Taboos surrounding female imagery – pregnancy, irregularity and ageing – are embraced in the form of the grotesque body, where they serve to destabilize the ideals of feminine beauty.Footnote 76

In Bakhtin’s carnivalesque, the grotesque body is in constant communication with the world it inhabits. It is a body ‘in the act of becoming. It is never finished, never completed; it is continually built, created, and builds and creates another body.’Footnote 77 The body interconnects with its world, and the old merges with the new in a continuous cycle of life. Bakhtin cites examples of Roman terracottas in the Ukrainian Kerch Museum depicting ‘senile pregnant hags’ as grotesque images that unite birth and death.Footnote 78 For him, the grotesque body celebrates, however subversively, the natural life cycle of birth and death, renewal and decay. Significantly, he notes that ‘the old hags are laughing’.Footnote 79 In the spirit of the joyful, exuberant and rebellious nature of carnival, laughter here can be connected with the apotropaic laughter of Baubo statuettes and perhaps the Louvre torso – and even our drunken old woman as well. Bodily openness is signalled by her orifices – nostrils, ears, mouth, anus – through which she merges with the world around her. The mouth has a special significance in that it both ingests food and produces words and, of course, festive laughter. The open laughing mouth of the drunken old woman symbolizes the connection of body and society; and, as with Bakhtin’s ‘senile pregnant hags’, the festive laughter that she emits presumes to challenge all fears, including the fear of death itself.

In a visual culture that privileges youthful female beauty, the old woman is not a staple subject in the repertoire of classical Greek art. In literature she is most obviously a comic stereotype that invites the audience or reader to laugh at the incongruity between an old woman’s libidinousness and the lack of desire that her ageing body provokes in potential sexual partners. Our Hellenistic drunken old woman certainly draws on such a comic tradition, and her dishabille is correspondingly at odds with her fragile body, just as her finery jars with her helplessly drunken condition. Nevertheless, she is not merely a figure of fun, and, in the spirit of the Bakhtinian carnivalesque, her open mouth seems to exude a loud, exuberant and communal noise which invites us to laugh, perhaps at her, but also with her. Transcending fear, pity and ridicule, she is a subversive figure who challenges expectations concerning sobriety, status, sexuality – and gender.