On ancient evidence, Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Cnidos is widely thought to have been the first free-standing female nude,Footnote 1 and, as such, she enters the art-historical canon as a site of aesthetic and erotic significance. The female nude comes to play an important role in classical art, and, within the classical tradition, she is to become so pervasive and instantly recognizable that she can be claimed as emblematic of art itself.Footnote 2 And yet this Aphrodite was conceived as a cult statue. She thus possessed a religious significance in a context where sacred and secular, personal and political – and gendered – ways of viewing merge for the making of artistic meaning.

Within the history of Western art, nudity and femininity come to be effectively equated, yet, as we have seen in the example of the Doryphoros, this was not always the case. In the sixth century BC it is the male body that is characteristically nude, while the kore, the female counterpart to the kouros, is heavily draped. In fifth-century sculpture, hints of the female body emerge beneath diaphanous drapery as specific enhancements of meaning. In the Centaur and Lapith metopes from the Parthenon (c. 440 BC: British Museum), the bare breasts of Lapith women struggling to escape from pursuing centaurs indicate the pathos and vulnerability of their plight. The slightly later ‘Sandal-Binder’ relief from the south balustrade of the Temple of Athena Nike (c. 420: Acropolis Museum, Athens) depicts the female personification of Victory bending to tie her sandal. Catenary loops of diaphanous drapery follow the outline of her form without showing the body itself. Her nudity is hinted at but not completely revealed, just as military victory is desirable but elusive.Footnote 3 By the beginning of the fourth century, sea nymphs from the Nereid Monument in Xanthos (c. 390–380: British Museum) are sporting wet-look drapery that reveals the navel, breasts and genitals. By the middle of the fourth century a woman’s body is gradually unclothed, and, from now on, the female nude comes to occupy a leading place in ancient monumental art.

In 1956 Clark’s The Nude sets up a distinction between nudity and nakedness in terms of aesthetic classification versus material reality. Two decades later, influential studies by Berger and by Mulvey cast doubt on Clark’s distinct categories and interrogate the viewer/viewed dynamic whereby the female body becomes objectified by the male gaze.Footnote 4 Since then, feminist art historians and film theorists have persistently challenged and redefined Mulvey’s premise, but, in spite of this, the Berger/Mulvey model is often applied to the Aphrodite sculpture unproblematically, on the premise that this female body is the site of heterosexual male desire.Footnote 5 While that approach has certainly yielded important information on gender dynamics in late-Classical Greece, it tends to overlook the fact that though this Aphrodite is female, she is also divine.Footnote 6 By invoking the now-established cultural-studies premise that it is viewers who make meanings, we are in a position to ask how a Greek woman might have looked at the Cnidia in a temple setting. Perhaps she saw the female nude not as a sexual object at all but as a positive celebration of feminine divinity?

Pliny the Elder, writing almost three centuries after her production, describes the Cnidia’s provenance, location and reception:

Praxiteles … made two statues and put them up for sale at the same time. One of them showed the body draped, and for this reason, even though he had put the same price on both, it was preferred by the people of Cos, who had an option on the sale, because they judged it to be the sober and proper thing to do. The people of Cnidos bought the rejected statue, the fame of which became vastly greater.Footnote 7

Whether or not the details of this story are historically accurate, Pliny’s description highlights the fact that an explanation is needed for the statue’s conception and, in particular, her nudity.Footnote 8 But assuming the story can be trusted, it would seem that Praxiteles did not receive a commission but produced cult statues for the open market, while the statue’s nudity proves to be a site of controversy anticipated by the sculptor, who made two statues, confident that, even if his innovative nude was rejected, a clothed Aphrodite would find a buyer.

The Cnidia’s nudity is customarily explained by a bathing motif. Her cult title at Cnidos was Aphrodite Euploia (Aphrodite ‘of the fair voyage’).Footnote 9 This is usually seen as a reference to the mythical journey of the goddess across the Mediterranean after her birth, during which she stops to wash the sea foam (aphros in Greek) from her body. In the fourth century BC, the city of Cnidos was rebuilt on the tip of a peninsula joined to the mainland by a causeway, with two deep harbours on either side. The temple looked down over both harbours, as if to affirm the cult title by which the goddess was worshipped there. Stewart argues plausibly that the Euploia title identifies Aphrodite as a sailor’s goddess and emphasizes her role in ensuring safe journeys across the sea rather than the narrative of her birth.Footnote 10 And the bathing motif, rather than a reference to the supposed sea-foam incident, might instead look to mythological descriptions of Aphrodite’s baths before and after sex, and, in particular, her pre-nuptial bath before her marriage to Hephaestus.Footnote 11 Yet even with the support of a more convincing narrative, the bath ritual still functions as an excuse for Aphrodite’s nudity, something that is not required of the Doryphoros or of other male nudes.Footnote 12

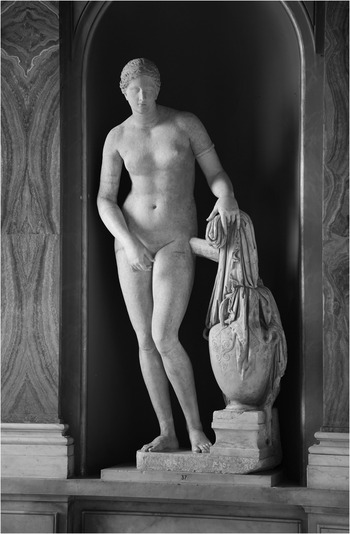

While Praxiteles’ original has not survived, copies, including the Colonna type in the Vatican Museum (Figure 5), show an elegant nude.Footnote 13 Like the Doryphoros, she has an ideal rather than an actual body, something underscored by her height: standing at around six and a half feet, the Cnidia is much bigger than the usual Greek woman of the fourth century. But while the male body is defined by muscles, the female is much softer, and the Cnidia has small, high breasts, along with rounded stomach and hips, accentuated by the contrapposto curve of her body.Footnote 14

Contemporary art-historical discussions of the female nude reject or reread Clark’s category of ‘aesthetic’ nudity, insisting that in any such representation the body is heavily invested with cultural meaning.Footnote 15 Nead sees the aestheticized nude as ‘a way of controlling the unruly female body’,Footnote 16 made up of an undisciplined mass of flesh, fat and orifices which can be disciplined and contained by an idealized and inviolable artistic transformation. But while the Cnidia’s aesthetic body proclaims her as an art object rather than a real woman, it also underscores Aphrodite’s divine nature by differentiating her from mortal women. The Greek view of divinity assumes that gods and goddesses only reluctantly show themselves to mortals.Footnote 17 This assumption is made explicit in a series of (largely) Hellenistic epigrams relating to the Cnidia in the Greek Anthology which foreground Aphrodite’s reaction to Praxiteles’ violation of the rules of viewing.Footnote 18 In one of the series, ascribed (in arbitrary later-antique fashion) to Plato, the goddess is astonished by the veracity of the statue:

Strikingly, some of the epigrams link the sculptor’s gaze with mythological precedents – Paris, Anchises, Adonis – and suggest that he grants the viewer a look that is forbidden in Greek myth.

In classical Greece, the statue of a divine figure celebrates, acclaims and, in an obvious sense, helps to localize the worship of that divinity; but does it in itself imply the actual presence of the god or goddess? Around 500 BC, the philosopher Heraclitus expresses his scorn for those who ‘pray to those statues, like people having a conversation with a house’ – rather, that is, than with the house’s owner.Footnote 20 Half a century later, conversely, Aeschylus’ Orestes comes to Athena’s temple, prays to the goddess and takes hold of her image, but has no difficulty distinguishing the two, any more than Athena herself, when she arrives to speak to ‘this stranger, sitting by my image’.Footnote 21 What do the Hellenistic epigrams about the Cnidia tell us about the relationship between statue and deity? Platt suggests that they blur the boundaries between the two and imply that the viewer has an actual epiphany of the goddess.Footnote 22 Morales argues that the poems belie anxieties surrounding viewership of the divine, but that, in order to assuage such concerns, the artistic process of picturing divinity must involve not just mimēsis (‘imitation’) but also phantasia (‘imagination’).Footnote 23 In any event, the poems seem to indicate that, so great is Praxiteles’ skill and creativity, the impression is given of a true likeness of divinity, so that, on one level or another, the viewer can believe that his statue is an actual realization of the goddess’s appearance.

Whether epiphany or imagination can explain the process of viewing the Cnidia, the epigrams certainly point to a problem involving any mortal seeing a naked goddess: a problem that is specifically centred on male viewership. The issue of gendered viewing comes most sharply into focus with interpretations of the statue’s gesture of moving the right hand in front of the genitals: the so-called pudica or modesty pose. For Blundell and Salomon, the pose assumes a narrative of female sexual vulnerability whereby the viewer is automatically positioned as voyeur,Footnote 24 while Osborne, concluding that she has nothing to say to women, also reads the Cnidia specifically in terms of male desire.Footnote 25 The three agree in interpreting the Aphrodite in terms of the Berger/Mulvey model of viewership: a figure of ultimate passivity, aware of being seen and attempting to conceal herself from the male gaze. Conversely, Stewart sees the protective hand as placed casually and ineffectively, thus prompting a reading not of submission but of invitation and inclusion.Footnote 26 Intriguingly, he also suggests that the statue’s sideways glance off to the right is directed at a notional viewer (possibly one of her named lovers and, if so, most probably Ares), with the arm gesture indeed protective, but only protective against us, her unknown viewers, rather than the known lover.Footnote 27 Even here, though, the familiar dynamic of viewing male and viewed female is invoked. If Aphrodite is revealing rather than concealing her genitals, she is still responding to the male ‘look’.

In all these interpretations, a woman’s reaction is ignored. In the wake of Mulvey’s argument that women take on the male role as viewers of themselves (and along with it, the objectifying and voyeuristic male gaze), film scholars have sought rather to identify an active female gaze in which women are able to see positive images of themselves when looking at other women. Stacey proposes that differently gendered spectator positions are liable to contradict the masculine model of viewership and that, even where a woman is displayed as sexual spectacle, a female viewer’s reaction ‘can vary across a wide spectrum between outright acceptance and refusal’.Footnote 28 Likewise, feminist art historians have re-examined the ways that women can look at images of other women. Pollock’s response to the works of van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec is to refuse to align her viewing experience with those of a male artist or a male voyeur, and instead to find her own feminist vantage point.Footnote 29 Women viewers, in fact, are well able to negotiate the complexities of gendered viewing and glean positive female meanings from male texts.

In the case of the Cnidia, we need to scrutinize the meaning of the goddess’s genitals – and the pudica pose that either points towards or shields them – if we are to explore further her meaning to the women, and indeed the men, who originally looked at her. Various scholars have argued convincingly that in antiquity the female genitals were understood (like their male equivalent) not only as sexual but also as apotropaic. Bonfante suggests that the sight of female breasts or genitals in divine iconography signifies fertility and power.Footnote 30 Johns notes that, although female genitals are rarely represented in plastic form in Greek culture, when the vulva is depicted, it can, like the phallus, connote power and good luck.Footnote 31 Textual sources give us the example of Baubo, the woman who causes apotropaic laughter when she exposes her vagina to the grieving Demeter.Footnote 32 Hellenistic and Roman terracotta statuettes of Baubo (Figure 6) show a squat woman with rounded breasts and belly; seated, she splays her legs to reveal her genitalia.Footnote 33 The exposure of female genitals can be traced to Assyrian imagery, where it is a sign of majesty and divinity.Footnote 34 Significantly, Baubo terracottas are smiling figures, flaunting an exuberant attitude to female sex and sexuality, and certainly apotropaic.

The Cnidia’s pudica pose derives, like Aphrodite herself, from the Near East – from the Levant or Cyprus,Footnote 35 or, in particular, from images of the Mesopotamian goddesses Ishtar or Inanna, who point to or caress their breasts or genitals. From the Neolithic to the Hellenistic periods, Mesopotamian female statuettes offer a shared iconography. Bahrani proposes that the images, often identified as fertility symbols, not only mark female sexuality as a source of procreation, but also acclaim it in terms of empowering desire.Footnote 36 These images and their feminist interpretations acquire a special relevance once we realize that the Cnidian Aphrodite has clear Near Eastern associations. The city of Cnidos, founded in the twelfth century by Dorian Greeks, is sited in the southern part of Caria in Asia Minor, where encounters with Near Eastern practices and iconography would have been prevalent. Stewart has drawn attention to the presence of miniature terracotta protomes of a goddess holding her breasts in the tholos terrace at Cnidos, thereby establishing that the Cnidia’s nudity and pose are most probably determined by Praxiteles’ referencing of non-Western models.Footnote 37

Evoking meaning as well as form, the Aphrodite of Cnidos’ genitals, like those of her Near Eastern ancestors, can be seen as a site of pleasure and power. Kousser rightly insists that the religious nature of the Cnidia needs to be taken into account when analysing her pudica gesture.Footnote 38 She argues that it is implausible that a cult statue calculated to inspire religious awe should invoke embarrassment and shame. Instead, the statue’s focus on her genitals must be drawing attention to the goddess’s authority over sex and sexuality. For a woman worshipper, then, the statue’s pudica pose can surely be read as showing the goddess of sexuality protecting her power. Seen in this light, the statue has a commanding rather than a submissive presence. Indeed, Stansbury-O’Donnell cites a Cnidia copy in the Munich Glyptothek as a figure that negates any thought of submissiveness by not looking down like the Vatican copy, but directly at the spectator.Footnote 39 He connects this pose with the language used by the Pseudo-Lucian, who characterizes the original Cnidia’s facial expression with the word huperēphanon, meaning ‘arrogant’ or ‘haughty’ but also ‘magnificent’.Footnote 40 The Aphrodite’s pudica pose, then, can certainly be credited with positive connotations of female eroticism.

But it is not just Aphrodite’s genitals that can claim an erotic focus. The circular tholos structure of the temple at Cnidos allowed the visitor to the shrine to admire the statue from the front and the back.Footnote 41 Buttocks as well as breasts and genitals were on display. The Pseudo-Lucian extols the beauty of the statue from all angles. In the course of a dialogue on the merits of woman-love versus boy-love, two friends – Charicles, a Corinthian who prefers women, and Callicratidas, an Athenian whose preference is for boys – visit the shrine at Cnidos. Callicratidas is left unmoved by the front view, but then:

he exclaimed with even greater enthusiasm than that of Charicles, ‘By Heracles, what a harmonious back. What rounded thighs, that beg to be caressed with both hands! How well the lines of her cheeks flow, neither too skinny, showing the bones, nor so voluminous as to droop! How inexpressible the tenderness of that smile pressed into her dimpled loins! How precise that line running from thigh, to leg, to foot!’Footnote 42

The two men notice a stain on the statue’s thigh, high up between the back of her legs, and are told by a temple attendant about a young man, who, enamoured of the Aphrodite, contrived to be locked into the temple at night and tried to have sex with the statue. The anecdote echoes (and very possibly derives from) a story told by Pliny in which ‘a certain man was overcome with love for the statue and, after hiding [in the shrine] during the night, he embraced it, and it bears a stain, as testimony to his lust’.Footnote 43 In a similar vein, Athenaeus records a story about a man who tries to penetrate another statue of Aphrodite, at Samos; he too fails – and resorts to a piece of meat.Footnote 44

In these anecdotes a man overcome with sexual desire attempts to consummate his love but fails.Footnote 45 The statue arouses human desire, but the men in question embrace not a woman but a nude. Recalling Nead’s contrast between the leaking, fleshy woman and the sealed and contained aesthetic nude, Creed stresses the undisciplined nature of the real female body, which, unlike its aesthetic counterpart, ‘is penetrable’ and also ‘changes shape, swells, gives birth, contracts, lactates, bleeds’.Footnote 46 Mahon’s examination of eroticism and art likewise insists on the gulf between woman and her representation: idealized form produces a ‘contained erotic tradition’ whereby sexual desire is a ‘staged’ encounter between object and viewer.Footnote 47

Although the Cnidia is desired as if she were a woman, she is in fact a nude. In such a case, sexual longing can never be satisfied, as vividly illustrated by the anecdotes of the men who tried to have sex with her. And it is relevant to note that Praxiteles’ statue, like other Greek nudes, is literally impenetrable because she has no vagina. The point has been made by classical art historians from Smith onwards. In his words:

It was a basic principle of Greek art that it records all the visible essentials of the human body. The smooth, unparted genital surface of the Aphrodites is a real and presumably highly significant departure from this principle. One may contrast the very detailed treatment of genitals on male statues. Indian sculpture, for example, has goddesses with finely carved sex-parts which rule out any bogus aesthetic argument for the Aphrodites. Accurate female genitals on statues, we can only surmise, might have been deemed too immodest, or have been felt unconsciously to be sexually too aggressive.Footnote 48

Female genitals could have been rendered in anatomically correct likeness in Greek statuary, but they are not.Footnote 49 The vagina is not entirely absent from Greek imagery: Baubo terracottas are, of course, one example, while another is provided by some votive models of body parts, which were a common feature of cult practice in fifth- and fourth-century mainland Greece. It is generally assumed that such models were dedicated in anticipation of, or in gratitude for, healing; and several votive vulvae have been found at the fourth-century sanctuary to Aphrodite along the Sacred Way between Athens and Eleusis, including one (dedicated by Philoumene) with the inscription, ‘Passers by, praise [the goddess]’.Footnote 50 Again (but in a different medium), in fifth-century vase painting, a tradition of representing naked prostitutes on symposium vases allows for a defined female anatomy. In sex scenes, the demarcation of labia is often apparent, while female genitals also become the focus of voyeuristic images detailing intimate bodily functions and grooming rituals. In a fifth-century kylix in the style of the Foundry Painter (Antikensammlung, Berlin), a squatting woman urinates into a basin; with legs extended, her pubic area is emphasized – and demarcated. Similarly, with legs splayed a woman singes her pubic hair in a red-figure kylix attributed to Onesimos (c. 500 BC: University of Mississippi Museum).Footnote 51

Smith tentatively suggests that anatomical detail on a public statue may have been excluded out of propriety, but he does not consider the divine status of the representation of a goddess. Stewart and Hales instead look to her religious significance and more plausibly propose that the Cnidia’s lack of genitalia denotes divinity.Footnote 52 In Greek myth, sexual unions between Aphrodite and mortal men are ultimately unsuccessful: Adonis is killed on a wild boar hunt, and Anchises is blinded or made lame by Zeus’ thunderbolt. In the case of the Aphrodite of Cnidos, any possibility of intercourse, along with its attendant dangers, is removed. Vernant has argued incisively that divine images were born out of the tension between a need to connect with the gods and an acknowledgement of the impossibility of such a connection:

The idea is to establish real contact with the world beyond, to actualize it, to make it present, and thereby to participate intimately in the divine; yet by the same move, it must also emphasize what is inaccessible and mysterious in divinity, its alien quality, its otherness.Footnote 53

In the case of the Cnidia, it is her believable and desirable nudity that makes her seem accessible, but her impenetrability that underscores her unreachable divinity.

According to Havelock, notwithstanding the later preoccupation with sexual responses aroused by the statue in the Hellenistic epigrammatists, Pliny and the Pseudo-Lucian, the Aphrodite’s original rationale was probably not to invite human lust at all but simply ‘to inspire religious awe’.Footnote 54 The Cnidia is, after all, a cult statue, an object in which there is profound sacred investment. Tanner points out that cult viewing took place on special occasions such as festivals or marriages. He identifies a characteristic reading of an Aphrodite cult statue on the occasion of a marriage, where the image has significance for both bride and groom.Footnote 55 The bride could feel herself the embodiment of the goddess’s sexual charm (kharis), while the groom might be aware of the erotic desire aroused by the goddess and his new wife. Tanner dismisses Osborne’s and Stewart’s identifications of the classical female nude as ‘high-class pornography’, and his own interpretation of the Aphrodite cult statue is more credibly informed by notions of the oppositional gaze. He concludes, convincingly, that the Aphrodite statue might elicit empathy from the female viewer or worshipper just as readily as desire from the male.

In a temple setting the Aphrodite’s divine nature was emphasized, but if a cult statue was desirable but impenetrable to men, this does not mean that she was also inaccessible to women. In the Greek Anthology, an epigram by the woman poet Nossis invites an all-female audience to visit Aphrodite’s temple in order to see a gold statue of the goddess dedicated by the hetaira Polyarchis.Footnote 56 The precious metal and sparkling surface might seem to distance the goddess from her mortal viewers, but the eagerness with which Nossis shares her invitation suggests that the image of the goddess still has a special meaning for them. That a statue of Aphrodite should be dedicated by a hetaira is not surprising given the cultic links between Aphrodite and Greek prostitution.Footnote 57 Praxiteles is even said to have claimed that he modelled the Cnidia on his lover, the hetaira Phryne,Footnote 58 and Phryne herself dedicated her own portrait and other statues at religious sanctuaries throughout Greece.Footnote 59

If prostitutes might have a good reason to worship the goddess of sexual love, she was important to other women as well. Addressing the possibility that women’s responses to the Cnidia might have been different from men’s, Kampen focuses on the reality of women as worshippers in sanctuaries throughout Greece and Greek Asia Minor from the fourth to the second century BC.Footnote 60 The evidence of a familial focus in dedicatory inscriptions to Aphrodite, mostly statue bases, by women for their husbands, children and parents, shows that these women are not prostitutes and that in worshipping the goddess they identify themselves as brides, wives, mothers and daughters. It is noteworthy that women are sometimes patrons of major art objects. A comparison can be drawn with later examples of female patronage. In nineteenth-century France, as Ockman has revealed, Ingres’s Grande Odalisque, often regarded as a textbook case of a passive female nude, was actually commissioned by a woman.Footnote 61 Around the same time, Canova’s statue, ‘Paolina Borghese as Venus Victrix’, a reclining semi-nude, was both commissioned and posed for by the same woman.Footnote 62 In such cases, images of the eroticized nude must obviously be read in terms of female patronage, viewership and taste. Likewise, in late-Classical Greece, women’s art patronage is testament to a female gaze that approaches the female nude in ways other than objectification. Just like the Doryphoros, the Cnidia too could surely evoke self-identification and desire in her female viewers.

Whether the nude is role model or sexually enticing image, the fact that Aphrodite appears on objects designed for female personal use in the private sphere is also significant. The goddess was evidently meaningful to the owners of perfume and cosmetic containers, jewellery and mirrors, adorned with her image. In a bronze repoussé mirror case from Paramythia (British Museum, London), roughly contemporary with Praxiteles’ Aphrodite, the goddess reclines next to her mortal lover Anchises. While the Trojan prince is dressed in full Eastern costume covering head, legs and arms, the goddess allows drapery to fall from her body, revealing her breasts and navel. In a society where marriage was a key female goal, Aphrodite represents a model of attractiveness. But this image is not just a patriarchal tool telling women how to conform to ideals of femininity: Aphrodite is a powerful goddess, of whom Anchises (leaning slightly away from her) is in visible awe.

As a goddess notorious for her love affairs, Aphrodite offers lessons in the art of seduction. It is she, after all, who lends Hera her girdle in order to seduce Zeus in the Iliad.Footnote 63 And yet, despite her own philandering behaviour, Aphrodite is worshipped as a protector of marriage: Athenian vase paintings show her as a member of a bridal party and even depict young brides sitting on her lap as she counsels them with maternal concern.Footnote 64 Aphrodite, then, assumes multiple roles: she is bridal mentor and love goddess and eroticized object of desire. To a modern viewer, these may seem contradictory parts to play, but our sensibility is, of course, very different from that of her original viewers. When we look at images on vases, we are inclined to differentiate between a clothed female as a representation of a ‘respectable’ married woman and an unclothed woman as a courtesan (hetaira) or a low prostitute (pornē), but, as scholars have come to realize, the identification of female status based on clothing or nudity alone is problematic.Footnote 65 A scene of a woman spinning might seem to be the commemorative image of an industrious wife, but if the woman has fine jewellery and an elaborate hairstyle, might she be a hetaira? In terms of self-recognition and emulation, the given activity and appearance in this scenario could make a hetaira respectable or a wife beautiful – depending on who is doing the looking. And if women viewers routinely negotiated the representation of status in vase painting, then differences and similarities in the depiction of human and divine, and, indeed, between art and life, were surely decoded likewise. Thus a woman looking at an image of a nude goddess would no doubt recognize the distinctions between herself and a divinity, and herself and an art object, but might also have found meaningful points of comparison.

Discussing cult statues (and with an eye on the Cnidia herself), Elsner pertinently observes that instead of one mode of viewing, these sculptures must have been subject to a whole spectrum of changing and interchanging viewings, which co-existed with one another.Footnote 66 For both women and men, the Aphrodite cult statue was venerated as an aesthetic embodiment of the deity, but she also offered alternative gendered meanings. Her nudity might seem to designate her as passive object of the male gaze, but her role in male fantasy did not preclude her from female fantasies as well.Footnote 67 The Pseudo-Lucian suggests that her rounded buttocks might even stimulate homoerotic desire. In her pudica pose, rather than shamefully concealing her sexuality, she may in fact be protecting the source of her power. And for a woman looking at the statue, such authority over an exposed body may well have offered a powerful emblem of female ego-identification.