Cold War Freud addresses the uneasy encounters of Freudian theories about desire, anxiety, aggression, guilt, trauma, and pleasure – and the very nature of the human self and its motivations – with the calamitous events of World War II and beyond. While psychoanalysis is often taken to be ahistorical in its view of human nature, the opposite is the case. The impact of epochal historical transformations on psychoanalytic premises and practices is particularly evident in the postwar decades. This was precisely when psychoanalysis gained the greatest traction, across the West, within medicine and mainstream belief alike. For in the course of the second half of the twentieth century, psychoanalytic thinking came consequentially to inflect virtually all other thought-systems – from the major religious traditions to the social science disciplines and from conventional advice literature to radical political protest movements. Psychoanalysis, in all its unruly complexity, became an integral part of twentieth-century social and intellectual history.

The heyday of intellectual and popular preoccupation with psychoanalysis reached from the 1940s to the 1980s – from postwar conservative consolidation to delayed-reaction engagement with the legacies of Nazism and the Holocaust, from the anti-Vietnam War movement and the concomitant inversion of generational and moral alignments to the confrontation with new Cold War dictatorships, and from the sexual revolution and the rise of women’s and gay rights to an intensified interest in learning from formerly colonized peoples in an – only unevenly – postcolonial world. The battles within and around psychoanalysis provided a language for thinking about the changes in what counted as truth about how human beings are, and what could and should be done about it. But the possible relationships between psychoanalysis and politics were fraught, and a permanent source of ambivalence.

Sigmund Freud died in 1939 in his London exile. Ever the self-reviser, he had tacked frequently between issues of clinical technique, anthropological speculation, and political opinion. For him, psychoanalysis was, at once, a therapeutic modality, a theory of human nature, and a toolbox for cultural criticism. In the years that followed, however, the irresolvable tensions between the therapeutic and the cultural-diagnostic potentials of psychoanalysis would be argued over not just by Freud’s detractors but also by his disciples. And the stakes had changed, drastically. The conflicts between the various possible uses of psychoanalytic thinking were especially intense in the wake of the rupture in civilization constituted by the wild success of Nazism in the 1930s and the unprecedented enormity of mass murder in the 1940s. This was not just because of the ensuing dispersion of the analytic community, but above all because of the stark questions posed by the historical events themselves. Psychoanalysis, it turned out, could have both normative-conservative and socially critical implications. And while its practitioners and promoters careened often between seeking to explain dynamics in the most intimate crevices of fantasies and bodies and venturing to pronounce on culture and politics in the broadest senses of those terms, there was never a self-evident relationship between the possible political implications of psychoanalytic precepts, left, middle, or right, on the one hand, and the niceties of psychotherapeutic method or theoretical formulation, on the other. And neither of these matters matched up easily with the declarations of rupture or of fealty to Freud made on all sides.

In 1949, the first post-World War II meeting of the International Psychoanalytical Association was held in Zurich. World events had kept the IPA from meeting for more than a decade. In Zurich, the Welsh-born, London-based neurologist and psychoanalyst Ernest Jones – President of the IPA, one of the most respected exponents of psychoanalysis in Britain, longtime editor of the International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, and soon to be Freud’s official biographer – addressed the audience with a plea to stay away not just from anything that could be construed as politically subversive. In fact, he urged them to stay away from discussion of extrapsychic factors of any kind.

Or perhaps it was more of an order than a plea. Jones directed his listeners to focus strictly on “the primitive forces of the mind” and to steer clear of “the influence of sociological factors.”1 In Jones’ view, the lesson to be drawn from the recent past – particularly in view of National Socialism’s conquest of much of the European continent along with the resultant acceleration of the psychoanalytic diaspora, as well as from the fact that, at the then-present moment, in countries on the other side of the Iron Curtain, psychoanalytic associations that had been shut down during the war were not being permitted to reconstitute themselves – was that politics of any kind was something best kept at arm’s length. Jones’ official justification for apoliticism, in short, lay in political events. (This justification was all the more peculiar, as it suppressed the fact that actually quite a bit of writing about such topics as war, aggression, and prejudice had been produced, also by British psychoanalysts, including Jones, in the 1930s and 1940s.)2 Or, as he framed his argument: “We have to resist the temptation to be carried away, to adopt emotional short cuts in our thinking, to follow the way of politicians, who, after all, have not been notably successful in adding to the happiness of the world.” But his was a multifunctional directive. For avoiding discussion of politics and of extrapsychic dynamics had the added benefit of erasing from view Jones’ own collusion with Sigmund and Anna Freud, during the war, in the exclusion of the Marxist psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich from the rescue operations extended to most other refugee analysts (due to Reich’s perceived political toxicity). And it had the further advantage of providing a formal repudiation of more sociologically oriented “neo-Freudian” trends that had come to prominence especially in the United States during the war years (and that Jones was interested in seeing shunted). Jones was adamant. While “the temptation is understandably great to add socio-political factors to those that are our special concern, and to re-read our findings in terms of sociology,” this was, he admonished – in a description that was actually a prescription – “a temptation which, one is proud to observe, has, with very few exceptions, been stoutly resisted.”3 Many psychoanalysts – in the USA, in Western and Central Europe and in Latin America – would come to heed Jones’ counsel, whether out of personal predilection or institutional pressures, or some combination of the two.

More than two decades and ten biennial meetings later, however, at the IPA congress in Vienna in 1971 – a meeting which Anna Freud, two years earlier, had agreed could be dedicated to studying the topic of aggression (the proposal to do so had been put forward by the Pakistani British psychoanalyst Masud Khan, the American Martin Wangh, and the Argentinean Arnaldo Rascovsky) – the eminent West German psychoanalyst Alexander Mitscherlich stood before his peers and demanded that they take sociological and political matters seriously. “All our theories are going to be carried away by history,” Mitscherlich told his colleagues, speaking on the topic of “Psychoanalysis and the Aggression of Large Groups” – “unless,” as newspapers from the Kansas City Times to the Herald Tribune in Paris summarized his argument, “psychoanalysis is applied to social problems.”4 One evident context for Mitscherlich’s remark was the war ongoing at that very moment in Vietnam. Indeed Mitscherlich went on to provoke his fellow analysts with warnings of how irrelevant their models and concepts of human nature would soon become with a fairly direct reference to that particular conflict: “I fear that nobody is going to take us very seriously if we continue to suggest that war comes about because fathers hate their sons and want to kill them, that war is filicide. We must, instead, aim at finding a theory that explains group behavior, a theory that traces this behavior to the conflicts in society that actuate the individual drives.”5 Mitscherlich also did not hesitate to invoke his own nation’s history, noting that “collective phenomena demand a different sort of understanding than can be acquired by treating neuroses. The behaviour of the German people during the Nazi rule and its aftermath showed how preshaped character structure and universal aggressive propaganda could dovetail into each other in a quite specific manner to allow the unthinkable to become reality.”6 Moreover, and pointing to such texts as Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921) and Civilization and its Discontents (1930), Mitscherlich reminded the audience that Sigmund Freud himself had been highly interested in political and cultural phenomena – and thus that concern with extrapsychic conditions and forces would in no way imply a departure from the master’s path. Nonetheless, and as the newspapers also reported, “Mitscherlich’s suggestion that destructive aggressive behavior is provoked by social factors runs counter to current Freudian orthodoxy – that aggression derives from internal psychic sources that are instinctual.”7 And while Mitscherlich’s politically engaged comments “evoked a burst of applause from younger participants [,][…] some of their elders sat in stony silence.”8 An emergent intergenerational, geographical, and ideological divide within the IPA had become unmistakable.

At the turn from the 1960s to the 1970s, the IPA was dominated by a handful of its British, but above all by its American members, many of whom Mitscherlich knew well from numerous travels and research stays in both countries.9 Why did Mitscherlich’s message not find a welcome resonance among his senior confreres? Mitscherlich’s barb – “all our theories are going to be carried away by history” – could sting his older American colleagues, and garner notice in the international press, not least because psychoanalysis in the USA was, in fact, at this moment, in a serious predicament. The “golden age” of American psychoanalysis that had run from roughly 1949 to 1969 was about to be brought to an end by the combined impact of: the feminist and gay rights movements with their numerous, highly valid complaints about the misogyny and homophobia endemic in postwar analysis; the rise of shorter-term and more behaviorally oriented therapies, but above all the explosion of pop self-help, much of which would expressly style itself in opposition to the expense and purported futility of years on the couch; and the antiauthoritarian climate in general. The turn inward and the emphasis on intrapsychic, or at most on intrafamilial, dynamics that had been so remarkably successful in the first two postwar decades had, in short, run aground.

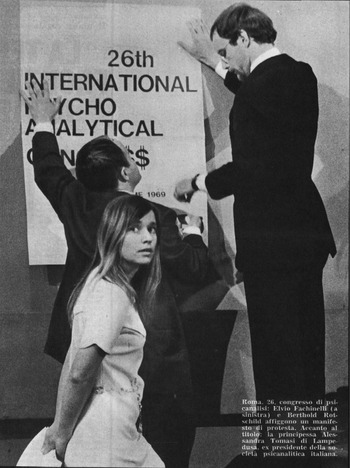

Already two years earlier, at the occasion of the IPA congress meeting in Rome in 1969, younger West German, Swiss, Italian, and French analysts and analysts-in-training had organized a “counter-congress” to register their dissent from what they perceived as the authoritarianism and inadequate engagement with social issues of the day among the leaders of the international psychoanalytic community. More than 100 participants showed up for several days of engaged discussion (at a restaurant within a fifth of a mile of the Cavalieri Hilton, where the registered congress participants were housed in upscale splendor). The IPA was accused – as the dollar signs replacing the final letters in the poster criticizing the main “Congre$$” made all too clear – of caring more about lucrative professional self-protection than about excellence in clinical practice, to say nothing of pressing political matters (see Figure 1).10 Mitscherlich – together with the Swiss psychoanalysts Paul Parin and Fritz Morgenthaler – had been among only a tiny handful of prominent senior members of the IPA who had shown support for the counter-congress (although Jacques Lacan had flown in from Paris when he learned how much excitement and media coverage the counter-congress was engendering).11 And Mitscherlich had also delivered a speech at the main congress in which he expressed sympathy for youth “protest and revolution.”12 In Rome, the young European dissidents, joined by several Latin American, especially Argentinean, analysts (notably also more senior Latin American psychoanalysts had been irritated by their inadequate representation among those regularly chosen to be IPA presenters), launched a network called “Plataforma.”13 This network would link radicals in Latin America and Europe for the duration of the next two decades – a linkage which was deeply to shape the subsequent clinical and conceptual work of the participants.14

Figure 1 Marianna Bolko, Elvio Fachinelli, and Berthold Rothschild – coorganizers of the “counter-congress” in Rome, July–August 1969 – hanging a poster critical of the International Psychoanalytical Association congress’ program and professional priorities. The accompanying article in the Italian magazine L’Espresso covered both the congress and the counter-congress, but was clearly most fascinated by what it described as the counter-congress’ claims that American psychoanalysts were “seeking hegemony over the unconscious.”

For, as it happened, psychoanalysis globally was not in decline. On the contrary, what was really going on was that the geographical and generational loci of creativity and influence were shifting. Psychoanalysis was about to enjoy a second “golden age,” this one within Western and Central Europe, and (although complicated both by brutal repressions and by self-interested complicities under several dictatorial regimes) also in Latin America.15 This second golden age, from the late 1960s through the late 1980s, was sustained not least by the New Left generation of 1968 and by those among their elders, Mitscherlich, Parin, and Morgenthaler among them, who were in sympathy with New Left concerns. The New Left was, simply, the major motor for the restoration and cultural consolidation of psychoanalysis in Western and Central Europe and for the further development of psychoanalysis in Latin America as well.16 But it was a distinctly different Freud that these rebels resurrected. Or rather: one could say that there was not one Freud circulating in the course of the Cold War era, and not even only a dozen, but rather hundreds.

We have been living through a contemporary moment of renewed interest in Freud and in the evolution of psychoanalysis. Already in 2006, the American historian John C. Burnham detected the emergence of a “historiographical shift” that he dubbed “The New Freud Studies.” Burnham observed that the opening to scholars of a massive archive of primary sources that had long been sealed from public access – especially the collection at the Sigmund Freud Archives at the US Library of Congress – would inevitably stimulate an efflorescence of fresh work. (Much of the material in that collection, which was begun in 1951 and includes a wealth of correspondence from the first half of the twentieth century as well as extensive interviews conducted in the early 1950s with dozens of individuals who knew Freud personally, has indeed, between 2000 and 2015, finally been derestricted.)17 Burnham surmised that because the history of psychoanalysis had for so long been written by insider-practitioners rather than historians, and that these insiders were unabashedly “using the history of psychoanalysis as a weapon in their struggles to control the medical, psychological, and philosophical understandings of Freud and the Freudians” – and hence tended to produce writing that “had its origin in whiggish justifications of later versions of theory and clinical practice” – the involvement of outsiders would change how the history of the field was told.18 And so it has been – although it remains critical to add that insider-practitioners have written superb histories as well, and may often have been better positioned to explicate such matters as the evolution of clinical technique (and, of course, there are individuals who are both analysts and historians and bring that double vision creatively to bear).19

One of the earliest results of fresh perspectives coming from outside, already in evidence in the midst of the so-called “Freud Wars” of the mid-1990s – wars over scholarly access to the archive but also over the meaning of Freud’s legacy – was a far deepened understanding of Freud’s own historical contextualization.20 Sander Gilman’s Freud, Race, and Gender (1994) signaled a move toward placing Freud more firmly in the antisemitic atmosphere of fin-de-siècle Vienna and the consequences of the “feminization” of male Jews for Freud’s theories of women; numerous scholars have since followed Gilman’s lead.21 Mari Jo Buhle’s marvelously lucid Feminism and Its Discontents: A Century of Struggle with Psychoanalysis (1998) and Eli Zaretsky’s pioneering Secrets of the Soul: A Social and Cultural History of Psychoanalysis (2004) took the story of the psychoanalytic movement forward, with both paying particular attention to the vicissitudes of its recurrent encounters with feminism and with both offering especially important insights into the development of psychoanalysis in the USA.22 But Burnham proved correct that additional access to theretofore unseen primary sources would allow a repositioning of Freud’s work in a yet richer matrix of alliances, rivalries, and mutual influencings.23 A stellar example of the insights gained was George Makari’s magisterial Revolution in Mind: The Creation of Psychoanalysis (2008).24 And in 2012 Burnham published an anthology, After Freud Left: A Century of Psychoanalysis in America, which brought together literary critics and historians to consider the place of psychoanalysis in key phases of US history.25

Since then, ever new areas of inquiry have opened up. Among other things, the increasing internationalization of historical research has complicated what we thought we knew about the early diffusion of psychoanalytic ideas. As the British historian John Forrester noted as recently as 2014: “Much of the history of psychoanalysis really is lost from sight – because we have been looking for too long in the wrong places.” In particular, Forrester continued – here echoing Burnham – “we have been taking on trust not only the official histories of psychoanalysis, suffering from all the distortions that winners’ history always introduces, … but also the presumption that key figures in later history were also central to the earlier phases of its history.”26 But another broad trend has been to redirect attention beyond Freud, toward post-Freudian actors and the by now nearly infinite permutations of Freudian concepts that have circulated, and been recirculated – and thereby repeatedly modified – and the many uses to which these concepts have been put. As Matt ffytche, Forrester’s successor as editor of the journal Psychoanalysis and History, noted in 2016:

Psychoanalytic history may begin with Freud and his colleagues, or thereabouts, but that was simply the opening chapter. What has become increasingly fascinating, for historians and psychoanalysts alike, are the multiple sequels beyond Vienna – in the 1930s, the 1950s, the 1980s and now the 2000s – during which psychoanalysis has reached across various geographical and cultural boundaries, and embedded itself in many other fields, including modern psychology, philosophy, literature, politics and the social sciences and humanities more broadly.27

The outpouring of new work within which Cold War Freud is situated has developed along two main axes. One encompasses histories locating post-Freudian actors either in national cultures or in transnational political conflicts – including explorations of the role of psychoanalytic ideas in colonial and postcolonial contexts. Among the most significant recent ones are Camille Robcis’ The Law of Kinship: Anthropology, Psychoanalysis, and the Family in France (2013), Michal Shapira’s The War Inside: Psychoanalysis, Total War and the Making of the Democratic Self in Postwar Britain (2013), Elizabeth Lunbeck’s The Americanization of Narcissism (2014), and Erik Linstrum’s Ruling Minds: Psychology in the British Empire (2016), as well as the anthologies edited by Mariano Ben Plotkin and Joy Damousi, Psychoanalysis and Politics: Histories of Psychoanalysis Under Conditions of Restricted Political Freedom (2012), and by Warwick Anderson, Deborah Jenson, and Richard C. Keller, Unconscious Dominions: Psychoanalysis, Colonial Trauma, and Global Sovereignties (2011).28 Also relevant here is the work-in-progress of Omnia El Shakry on “The Arabic Freud: The Unconscious and the Modern Subject.”29 Several books within this cluster are specifically concerned to recover politically committed versions of psychoanalysis. The most noteworthy of these are A Psychotherapy for the People: Toward a Progressive Psychoanalysis (2012), co-written by the psychoanalysts Lewis Aron and Karen Starr, and historian Eli Zaretsky’s Political Freud: A History (2015); among Zaretsky’s foci are the historical uses made of psychoanalysis by African American activists.30 The other cluster of scholarship, at times overlapping with the first, and following on a prior wave of preoccupation with feminist challenges to the psychoanalytic movement, involves the efflorescence of histories pursuing “queerer” readings of psychoanalysis and seeking to make sense of the depth and doggedness of the homophobia that became practically endemic to the psychoanalytic movement, despite Freud’s own repudiation of it. This group could be said to have its roots in a special issue of GLQ published in 1995: Pink Freud, edited by the literary critic Diana Fuss.31 Since then, it has been growing steadily, although it has tended to draw in psychoanalysts and cultural studies scholars more than historians.32

Cold War Freud adds to these studies in multiple ways. Each of the six chapters takes up a different set of at once ethically and politically intense and long-perplexing, even stubbornly refractory, issues. They include: the relation of psychoanalysis to organized religion at the very onset of the Cold War; the tenaciously flexible hold of hostility to homosexuality; the striking time lag in acknowledging the existence of massive psychic trauma in the wake of the Holocaust; the unique trajectory of conflicts over whether aggression might be an innate feature in the human animal as these evolved in intergenerational battles in the aftermath of Nazism; the limits of an Oedipalized model of selfhood for understanding the workings of politics in conditions of globalizing capitalism; and the possibilities of acquiring a critical vantage on the cultures of the former colonizers by engaging the perspectives of the formerly colonized. As this brief list already suggests, the recurrent themes all somehow involve desire, violence, and relations of power. Or, to invoke the words of the venerable conservative sociologist and critic (and Freud expert) Philip Rieff, they each involve humans’ struggle to “mediat[e] between culture and the instinct.”33 What is noteworthy as well is that they all demonstrate just how impracticable it was for postwar psychoanalysts to pretend they could be politically abstemious. Ambivalence and caution about politics made sense; thoughtful analysts recurrently declared that it would be absurd to extrapolate from models of human nature developed by studying individuals to groups and nations.34 And needless to say, there were numerous analysts whose genius lay in their clinical technique and who had nothing much to say about politics, nor should they have been expected to; the extraordinarily gifted Donald Winnicott is perhaps the consummate – most prominent and most enduringly influential – example of this type.35 On the other hand, however, too strong a renunciation of the world outside the consulting-room caused many analysts to miss – or deny – the inescapable reality of continual mutual imbrication of selves and societies. And what the historical episodes in the chapters that follow reveal as well is that the world kept coming back of its own accord, pressuring all the players in the unfolding controversies to engage in moral-political and not just clinical reasoning, no matter which side of which issue they found themselves on.36

Part i of this book discusses the overdetermined trend toward sexual conservatism in the forms taken by psychoanalysis in the postwar USA – manifest in its florid misogyny and homophobia. It accounts for the turn inward, away from critical engagement with politics with the exception of sexual politics. Chapter 1 explores the complex combination of a deliberate desexualization of post-Freudian psychoanalytic theory with the maintenance of Freudianism’s titillating reputation, and positions this within an active rapprochement with mainstream Christianity, Catholic as well as Protestant, a Christianity that was itself at that historical moment in the process of being transformed. Psychoanalysis, I argue, so often shorthanded as “the Jewish science,” might in fact better be described as undergoing a kind of “Christianization” – even as Christianity, like Judaism, was at that moment also becoming more “psychologized.” But this chapter additionally makes an argument for recovering the work of the psychoanalyst Karen Horney – not in the terms in which she is usually understood, especially her feminist challenges to Freud, but for her innovative reflections on how one might better conceptualize the relationship between sex and other realms of life – and then shows how rivalrous irritation at Horney’s popularity constrained her successors’ maneuvering room in the face of attacks from religious leaders. Chapter 2, in turn, has at its center the problem of psychoanalytic homophobia while also examining the impact of loosening sexual mores and the ascent of competing sexological research – from Alfred Kinsey to William Masters and Virginia Johnson – as heretofore underestimated but key factors in the stages leading up to the eventual abrupt decline of psychoanalysis’ prestige in the later 1960s and 1970s, within psychiatry and within US culture as a whole. In addition, the chapter assesses the attempted self-renovation of American psychoanalysis in its tactical shift of focus to theories of narcissism, deficient selves, and character disorders – as it also traces the beginnings of efforts to revitalize psychoanalysis for anti-heteronormative and pro-sex feminist purposes, with particular attention to the ingenious and inspired arguments of Robert Stoller and Kenneth Lewes.

Part ii documents the quite unforeseen but profound consequences of the return to political relevance of the Nazi past on both sides of the Atlantic. Chapter 3 charts the clashes that ensued between pro- as well as anti-psychoanalytic psychiatrists in the USA, Europe, and Israel over the often delayed-reaction post-catastrophic emotional damages evinced by survivors of Nazi persecutions and the grotesque violence and sadism pervasive in concentration and death camps. Emphasizing the resurgence of antisemitism and resentment against survivors within West Germany, the chapter examines both the startling appropriation of Freudian concepts by physicians antagonistic to the survivors as well as the eventual creation, by sympathetic psychoanalysts and psychiatrists – through the contingent but crucial conjoining of survivors’ concerns with those of Vietnam War veterans and antiwar activists – of the syndrome now known as PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). It introduces the distinctive contributions into this debate of Kurt Eissler, more usually known to historians as the founding director of the aforementioned Freud Archives.37 Yet the chapter traces as well the inherent limits in the diagnostic category of PTSD as it was ultimately formulated, not least as the category was put to the test in Latin American psychotherapists’ efforts to provide care for survivors of torture.

Chapter 4 looks at the complicated process involved in returning psychoanalysis to cultural prestige in post-Nazi Germany. The chapter is centered on recovering and reinterpreting the work of Alexander Mitscherlich, the leading protagonist in the project of bringing psychoanalysis back to a land in which it had been denigrated as “Jewish” and “filthy,” and it is concerned to bring into view Mitscherlich’s particular strategic mix of ego psychological concepts with left-liberal recommendations for tolerance and social engagement. Yet the chapter makes an argument that considerable credit needs to be given to animal behavior expert Konrad Lorenz’s bestselling book On Aggression for setting in motion an unusually heated nationwide debate not only over whether human aggression was simply natural and inevitable and even a positive (i.e., not a German specialty and nothing Germans needed to be particularly ashamed of) but also, and specifically, over what exactly Freud had initially meant when he suggested that aggression might be a drive comparable in strength and form to libido. In a final section, this chapter explicates the long-delayed but then enthusiastic reception in Central Europe of British analyst Melanie Klein’s ideas about innate aggression.

Part iii turns to two case studies in what can only be called radical Freudianism. Both chapters are concerned with inventive appropriations of psychoanalytic concepts initially developed by tendentially nonpolitical analysts in earlier decades – but on the basis of thoroughly distinct psychoanalytic models, with one protagonist working from a model of the self as in tumultuous disarray, while the others relied on an assessment of selves as integrated albeit profoundly culturally inflected, and/or as sometimes damaged but potentially reparable. Chapter 5 turns to France to revisit philosopher Gilles Deleuze and psychoanalyst Félix Guattari’s countercultural classic Anti-Oedipus (1972) – with its giddy but simultaneously earnest splicing of ideas taken not only from the work of such overtly political psychoanalysts as Reich and Frantz Fanon, but also from Klein and Lacan – as well as an array of Guattari’s earlier and subsequent writings. The chapter makes a case for Guattari as not just a critic of stultifying existing forms of psychoanalysis – and especially of its much-mythologized icon, Oedipus, and the narrowly familialist framework of interpretation of psychic difficulties for which that icon stood – but also as a resourceful revitalizer of the psychoanalytic enterprise. This enterprise was, under the impact not least of the sexual revolution, feminism, and gay rights as well as anticolonial and antiwar activism, undergoing substantial transformation, and Guattari – reviving but respinning for his present older psychoanalytic theories of the appeals of fascism – also brought his experience working in alternative-experimental psychiatric institutions to his observations of Cold War politics. Chapter 6 reconsiders the pioneering fieldwork of the Swiss ethnographer-psychoanalysts Paul Parin, Fritz Morgenthaler, and Goldy Parin-Matthèy in Mali, Ivory Coast, and Papua New Guinea against the backstory of decades of merger and mutual borrowing as well as disputation between psychoanalysis and anthropology. It discusses the trio’s attempts to adapt psychoanalytic ideas about psychosexual stages, ego structure, Oedipal conflicts, defenses, and resistances to study non-Western selves in order to explore the enduring enigma of the relationships between nature and culture and the ways social contexts enter into and shape the innermost recesses of individual psyches. And finally, the chapter recounts the rise of the Parins and Morgenthaler to countercultural fame as it also explores how their cross-cultural experiments in the so-called Third World came to inform the stands they took on the politics of the First (including, notably, the sexual politics).

In its reconstruction of the dialectical and recursive interaction between these older radicals and the many young leftists they would inspire, this last chapter brings forward explicitly a larger argument that is only implicit in the earlier parts of the book. The history of psychoanalysis in general, it seems, has been one of countless delayed-reaction receptions, unplanned repurposings, and an ever-evolving reshaping of the meanings of texts and concepts. In the history of psychoanalysis, what a particular reading, a particular understanding, has facilitated – emotionally, politically, intellectually – has often been more important than what was said in the first place. There has never been an essential, self-evident content to the ideas that traveled into new contexts. Far from offering unchanging truths (or, for that matter, unchanging falsehoods), psychoanalysis has turned out to be only and always iridescent.

Meanwhile, another theme that recurs throughout the book has to do with the history of sexuality. There is no question that psychoanalysis as a twentieth-century phenomenon was utterly enmeshed with cultural conflicts over the status and meaning of sex. After all, the birth of psychoanalysis as a thought-system at the turn from the nineteenth to the twentieth century had been itself a symptom, and by no means just a cause, of an at least partial liberalization of sexual mores in Central Europe – and indeed psychoanalysis was just one of many in a welter of competing and overlapping thought-systems arising at the turn of the century to grapple with issues of gender and desire. Sexologists and other medical professionals, feminists, and homosexual rights activists, as well as moral reformers across the ideological spectrum, fought vehemently over such matters as prostitution and marriage, contraception and satisfaction, perversion and orientation. The emergence of psychoanalysis cannot be understood apart from this wider context; Freud and his first followers, as well as defectors and adapters, were in continual conversation with the trends of the era. Moreover, the subsequent evolution of the psychoanalytic theoretical edifice would be deeply shaped by the oscillation, in later decades – and differently in every country – between sexually conservative backlashes and efforts at renewed liberalization.38

What makes probing the history of psychoanalysis such an interesting problem also for historians of sexuality, then, is the fact that psychoanalysis, like the many schools of thought which borrowed from it, did not only theorize sex per se, but continually wrestled with the riddle of the relationships between sexual desire and other aspects of human motivation – from anaclitic, nonsexual longings for interpersonal connection to anxiety, aggression, and ambition. For some psychoanalytic commentators, sex – desires or troubles – explained just about everything. For others, the causation was completely reversed: sex was about everything but itself; nonsexual issues – including, precisely, ambition, aggression, and anxiety – were continually being worked through in the realm of sex. The puzzle of how to make sense of such matters as the sexualization of nonsexual impulses exercised analysts who were otherwise politically divergent. The question of what exactly people sought in sex – much of which may not, in its origins, have been sexual at all – helped some analysts to develop entirely new frames for analytic thinking. The insistence that the sexual and the economic realms were simply not categorically distinct provided grounds for others for retheorizing the emotional pulls by which all politics functioned. And a fascination with how hetero- and homosexuals alike reworked early traumas in order to turn them into sexual excitement helped yet others to facilitate empathy with sexual minorities and make a mockery of those of their peers who persisted in clinging to prejudicial views.

There is much that we still need to mull about the possible impact of the sexual revolution as a factor in the decline of psychoanalysis’ cachet in the USA in the later 1960s and 1970s – exactly the years when psychoanalysis’ fortunes were rising again in Western and Central Europe, as well as Latin America. Especially where and when sexual mores relaxed, increasing numbers of commentators claimed that it no longer made sense to assume that sexual repression was a key source of human problems.39 And yet over and over, in culture after culture, as conflicts over sexuality returned in new forms, perceptive observers and impassioned activists alike found that psychoanalytic concepts, however necessarily adapted, remained indispensable for making sense of human dreams and difficulties at the intersections of sexuality and the rest of life. To be sure, “repression” might long since no longer be the best way to think about the relationship between “the sexual” and other realms of existence. But psychoanalytic concepts would continue to be crucial references for grappling with matters as diverse as: the utter inextricability of social context and psychic interiority; the place of ambivalence and the meaning of conflict in intimate relationships; the apparent complexity – even inscrutability – of the relationships between excitement and satisfaction; and the extraordinary power of the unconscious in fantasies and behaviors alike.

All of this, in turn, raises intriguing questions about the opacity of historical causation in the realm of battles over meaning. Almost all the chapters engage the puzzle of major paradigm shifts in areas consequential for law, policy, and/or cultural commonsense – as well as some of the frequent unintended side-effects of such shifts. How do some ideas triumph and take enduring hold, while others are defeated or lost from view? And how might we explain the fact that very similar, even identical, concepts could be put to use for quite opposite agendas? How was it that a passionate investment in the notion of drives, for instance, could coexist with culturally conservative, tolerantly liberal, or subversive-transgressive political visions?40 How could a belief in inner chaos animate avowedly apolitical and ardently anarcho-politically engaged projects alike? Simultaneously, and conversely, how was it that individuals working from utterly irreconcilable models of human motivation – for example, analysts convinced of the universality of the Oedipus complex and analysts who found the notion beyond preposterous – could nonetheless find themselves on the same side of a contested political divide? My aim throughout has been to relocate each eventual paradigm shift in the complexity of its originating historical context, to show how terms got set and why – and with what often counterintuitive results. But another aim has been to explore what happens when theories travel and when concepts float loose from their original moorings.

In sum, a reading of several decades of psychoanalytic texts can provide a history of the vicissitudes of human nature, culture, politics, and sexuality not least because psychoanalysis has been not only a (variously proud, defensive, banal, insightful, bizarre, and influential) movement-sect-guild-profession-faith-discipline as well as an interactive treatment technique for emotional troubles. Rather, the practitioners and proponents of psychoanalysis have also, in the movement’s long and strange career, generated a set of conceptual tools that remain potentially quite useful for critical political and cultural analysis. Twenty-first-century pharmaceutical and neuroscientific research – often bent on ignoring social context and interpersonal relations and intent on refiguring selfhood as a matter mostly of chemical reactions and/or encoding in the genes – has had very little to say, for example, about such crucial features of human existence as conflicting desires, the instabilities of meanings, or the ever-mysterious relationships between psychic interiority and social context. Psychoanalysis, in all its contradictions, absurdities, and self-revisions, can contribute a great deal on precisely these matters.