A defining feature of Margaret Archer’s sociological project since the late 1980s has been the centrality she gives to the relationships between ‘structure’ and ‘agency’. While this is not in itself an original claim, only Archer has arguably devoted a trilogy to advance a systematic understanding of ‘culture’ (Archer Reference Archer1988), ‘social structures’ (Archer Reference Archer1995) and ‘agency’ (Archer Reference Archer2000). In these books, she offers not only a positive account of each of these domains in its own right but also, and equally importantly, she discusses their interrelationships.

When contemporary sociologists emphasise the importance of structure and agency as the discipline’s key dichotomy, the argument is usually made on cognitive grounds. They are all more or less agreed on the idea that at stake here are the conceptual, epistemological, methodological and even ontological implications that this tension poses to social theorising and to empirical research (Elder-Vass Reference Elder-Vass2010, Mascareño Reference Mascareño2008, Mouzelis Reference Mouzelis1995). The problem of structure and agency then becomes one particular way in which contemporary sociological theorists refer to the tensional relationships between, say, sociology’s older debate on action and system theory (Parsons Reference Parsons, Parsons, Shills, Naegele and Pitt1961), social and system integration (Habermas 1984a, Lockwood Reference Lockwood and Lockwood1992) or indeed micro vs macro (Alexander et al. Reference Alexander, Giesen, Münch and Smelser1987).Footnote 1 None of these debates coincides exactly with the one between structure and agency, but the main reason that explains why it resonates within the discipline, it seems to me, is because it simultaneously touches on such perennial dilemmas as objectivism and subjectivism, positivism and historicism or hermeneutics, and indeed the ‘external’ perspective of the scientific observer and the ‘internal’ perspective of lay actors themselves (see also Chapters 5 and 8).

In her well-known discussion of ‘upward’, ‘downward’ and ‘central’ conflation, Archer (Reference Archer1995) also unpacks some of these issues. As she reasons on the imitations of approaches that favour one side of this dualism over the other, a key point for Archer is to reject the offers of recent approaches in social theory which, rather than emphasising one side in detriment of the other, suggest that the solution is to be found at that ‘middle ground’ or ‘intersection’ between structure and agency. Theories that thus emphasise the ‘co-constitution’ of structure and agency can claim to have transcended previous dichotomies but are instead found guilty of committing to a theoretical strategy that is unable to account for the emergence, i.e. the autonomy and causal efficaciousness, of agency, social structures and culture. Thus, individualist positions which are committed to upward conflation range from J. S. Mills’s nineteenth-century utilitarianism to the rational choice theorists via modern ‘scientific’ psychology; collectivist standpoints that favour downward conflation are represented by a variety of writers that range from Rom Harré to Richard Rorty via Michael Foucault and several variants of structuralism and, finally, central conflationist include such figures as G. H. Mead, Anthony Giddens and Pierre Bourdieu.Footnote 2

It is not my intention to revise here the various arguments and counterarguments on the structure and agency debate, but I should like to step back and revisit some of the reasons that make it such a central topic of discussion. For the purposes of the project of a philosophical sociology that is interested in looking at our preconceptions of the human, there are two arguments in Archer’s work that have proved key. First, conflationist solutions are to be avoided because they by definition reject the autonomy of the human I am interrogating here. Second, behind all the work that has been done on theoretical critique, Archer contends, there is a main justification for the relevance of structure and agency in sociology that is not of conceptual nature: the sociological centrality of structure and agency is sustained by the fact that it is constitutive of the human condition itself. Structure and agency matter because this is a way in which sociology is able to capture one of the most fundamentally human way of experiencing life in society. Partly free, autonomous and enabled by structural circumstances, but also partly restricted, constrained and even conditioned by them, this tension mirrors the ways in which human beings themselves experience most aspects of their everyday lives. Thus, in the opening chapter of Realist Social Theory, Archer contends that this is a key phenomenological dimension of human existence and speaks of the undeniable ‘authenticity’ in ‘the human experience that we are both free and constrained’; an experience, moreover, that derives ‘from what we are as people and how we tacitly understand our social context’ (Reference Archer1995: 29). In seeking to come to grips with this challenge, the sociologist has no immediate cognitive privilege over what lay members of society may be able to claim on how society works. What makes sociological explanations adequate is to be assessed not only by such scientific criteria as conceptual integrity and empirical purchase but also by the way in which they resonate with this ultimate ambivalence that makes up most of our human experiences. It is above all the ability to offer causal explanations that also makes sense to people that becomes the ultimate ‘touchstone of adequate social theorizing’ (Reference Archer1995: 29). The argument is in effect that the fundamental theoretical predicament of the sociologist is directly dependent on the fundamentally human experience of society:

The vexatious task of understanding the linkage between ‘structure and agency’ will always retain this centrality because it derives from what society intrinsically is. Nor is the problem confined to those explicitly studying society, for each human being is confronted by it every day of their social life … such ambivalence in the daily experience of ordinary people is fully authentic.

A similar argument is also introduced as one of the key conclusions to her following volume Being Human. Given that the focus in that book is precisely on unpacking a conception of agency, it is fitting that the argument is now explicitly introduced in terms that speak of a universalistic principle of humanity:

[T]hree of our major problems in social theory are in fact interrelated. These are the “problem of structure and agency”, the “problem of subjectivism and objectivism”, and the “problem of agency”. All hinge, in various ways, upon the causal powers of people, their nature, emergence and efficacy … it will only be the re-emergence of humanity, meaning that due acknowledgement is given to the properties and powers of real people forged in the real world, which overcomes the present poverty of social theory.

This offer of an explicit articulation of a universalistic principle of humanity remains extremely rare in contemporary sociology and social theory (see, however, Chapter 8). Indeed, following our discussion on humanism in the Introduction, the argument can be made that it has taken sociology nearly half a century to re-engage with this problem. Archer is interested in making explicit a principle of humanity because this is a necessary step if we are going to succeed in raising the fundamental sociological questions about the relationships between structure and agency. A principle of humanity effectively makes social life possible – in her own formulation ‘no people: no society’ – and she also contends that our humanity remains autonomous from and is therefore irreducible to social and cultural forces. In turn, this has led her to explore, both empirically and theoretically, our human powers of reflexivity and internal conversation as they become the unique and specific contributions of our humanity to life in society (Reference Archer2003, Reference Archer2007, Reference Archer2012). Building on Archer, we can say that an explicit argument about the human is an integral part of a sociological understanding of social life.

There will be two main arguments in this chapter. The first seeks to explain and then assess the reasons – theoretical, methodological and indeed normative – that led Archer to contend that the unpacking of a universalistic principle of humanity is a necessary task for sociological research. While this is not a task that sociology can fulfil on its own, she equally contends that understanding humanity’s specific contribution to social life is not a marginal philosophical question that is to be added onto proper sociological enquiry; rather, it is integral to sociology itself.Footnote 3 My second task shall be to explore in some detail what are the main substantive elements that define Archer’s principle of humanity. Here, we will encounter such issues as a universal and continuous sense of self, human beings’ pre-social powers whose actualisation is only efficacious in society, and our human relationships with the practical order. Her more recent work on reflexivity and the internal conversation shall then emerge as the leading dimensions that account for what is unique about human beings.

I

The full elaboration of a principle of humanity in Archer’s work will make use of developments in various scientific disciplines and philosophical traditions – from qualitative interviews to neuroscience via, among others, Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology and Charles Pierce’s pragmatism. But we can start with an argument that works mostly within sociology. In Realist Social Theory, one main reason she offers for this project is methodological: a universalistic principle of humanity is the condition of possibility of what is arguably one of the most traditional areas of sociological investigation: historical–comparative sociology. The need for a principle of humanity arises out of sociology’s interest in ‘understanding those of other times and places who live by other institutions’. Without such a sense of continuity in what makes us humans, Archer contends, the very possibility of keeping some ‘thread of intelligibility’ will simply fall apart (Reference Archer1995: 281). The argument is that the very possibility of understanding other historical and cultural contexts as historically and culturally different from our own depends on the fact that those who lived and experienced them are the same kind of beings as we are: humans who create cultural artefacts and then experience and handle them in the ways that only humans do. A different but related methodological argument is that a universalistic principle of humanity alone can provide us with stable and continuous parameters so that sociology can go out and explore cultural variability and social change: ‘[h]umanity, as a natural kind, defies transmutation into another and different kind. It is this which sustains the thread of intelligibility between people of different times and places, and without it the thread would break’ (Reference Archer2000: 17).

In other words, the successful study of events in other times, places and cultural contexts is predicated on the fact that all members of the human species share some autonomous properties so that past, present and indeed future humans may develop a sense of transhistorical empathy that overrides, or rather underpins, their enormous sociocultural differences.Footnote 4 Sociological research devotes its primary attention to those collectives we call social agents and actors, but the projects that they hold dear and the ways in which they go about carrying them out cannot be dissociated from implicit notions of humanity: on the contrary, they remain the ‘a prioristic anchorage for the understanding of both … The human being thus remains the alpha and omega of Agents and Actors (whose genesis can never lead to exodus from humankind)’ (Reference Archer1995: 281). However thin and tentative, and regardless of whatever may get lost in the process, as social scientists we act as if human experiences can be understood, shared and then communicated. Our empirical propositions in the social sciences require us to presuppose that the subjects of our studies, and us researchers, share some attributes as part of the same species. We seek to understand experiences of change, variability and conflict by looking at the different ways in which social life can be organised. But we only recognise different social forms because we are able to trace them back to our shared human belonging: in any of the stories sociology tells, the subjects out there could well have been us.Footnote 5

Up to now, this methodological justification for a principle of humanity has focused on the requirements of historical–comparative research. But an additional argument is now added; one that does not operate in the long-term coordinates of macro historical processes but on the much shorter time-span of an individual’s biography. Archer contends that any sense of personal identity and degree of continuity about experiencing my life as my own becomes impossible ‘unless there is self-awareness that it is the same self who has interests upon which constraints and enablements impinge and that how they react today will affect what interests they will have tomorrow’ (Reference Archer1995: 282). From such practical skills as swimming or roller-skating to the specifics of our professional roles, from learning how to speak a new language to our irrational allegiance to a particular football team, human action is built on this self who knows about its own past and is able to devise fallible projects for the future: ‘processes like self and social monitoring, goal formation and articulation, or strategic reflection on means–ends relations … are themselves dependent upon more primitive properties of person’s (Reference Archer1995: 281). The sense of self we are talking about here is ‘prior to, and primitive to, our sociality’ (Reference Archer1995: 284).Footnote 6 At this methodological level, then, the key argument is the need for an ultimate human grounding of all sociological explanations: ‘the arguments presented here about what kinds of social beings people become are all anchored in the fact that it is human beings who do the becoming’ (Reference Archer1995: 281). The social sciences operate within a strict immanent framework – human behaviour is to be explained exclusively by recourse to items that are themselves understandable by humans – and this notion is implicitly built on a universalistic principle of humanity.

But Archer’s interest in the positive articulation of a universalistic principle of humanity does not end with the methodological quest for the production of social knowledge that can be used in various socio-historical contexts. Indeed, a major insight of the realist tradition is that methodological arguments are neither self-contained nor do they stand in a substantive vacuum; rather, they are fundamentally intertwined with conceptual and ultimately ontological propositions (Reference Archer1995: 1–30). There is a specifically theoretical need for the positive determination of those substantive properties of human beings that allow for the creation of recreation of social life. Below we will comment on the role of human reflexivity in that context, but before we do so we need to discuss the fundamental philosophical underpinning of that argument on reflexivity: human beings are emergent, i.e. independent, autonomous and causally efficacious, in relation to cultural and social forces.

Archer’s argument here is that human beings possess uninterrupted consciousness so that a continuous ‘sense of self’ becomes ‘the indispensable contribution which our humanity makes to our social life’ (Reference Archer1995: 282). As she expands on this argument, Archer takes up Marcel Mauss’s distinction between a concept of the self, which is socially construed and thus historically and culturally variable, and a sense of self that is pre-social and universal: all human beings in all cultures have a sense of ‘I’ (Reference Archer1995: 283).Footnote 7 If this partial withdrawal of social conditioning sounds counterintuitive for a sociological audience, she contends that this results from the ‘persistent tendency … to absorb the sense into the concept, and thus to credit a human universal to the effects of culture’ (Reference Archer2000: 125). This sense of self will require conceptual articulation but, as we shall also see below, its main feature is the fact that it is embodied and private rather than discursive and public (Reference Archer2000: 125). Indeed, her very idea of continuity of consciousness is predicated on the twin facts of our bodily constitution and its natural needs: ‘the bodies of the members of the human species and the genetic characteristics of this “species being” […] are necessarily pre-social at any given point in time’ (Reference Archer1995: 286). The transhistorical character of these human properties speaks for their independence from society: they are of course exercised in pre-structured social and cultural contexts, but as properties they remain fundamentally independent from social life.

Because both arguments are fundamentally intertwined – bodily constitution and continuous sense of self – Archer can now pre-empt the charge of being found guilty of physicalist reductionism. The continuity of consciousness in a human body is central for the constitution of full personhood so that, although the body ‘does not constitute the person, it defines who can be persons and also constrains what such people can do … human beings must have a particular physical constitution for them to be consistently socially influenced’ (Reference Archer1995: 287–8). In other words, our ability to have concepts of the self and of the social is already dependent upon the fact that we are ‘the kind of (human) being who can master social concepts … the distinguishing of social objects cannot be a predicate but only a derivative of a general human capacity to make distinctions’ (Reference Archer1995: 286). However central social life is in the ultimate actualisation of our human potentials, society is neither the only source of these potentials nor the only domain with which humans interact:

it is precisely because of our interaction with the natural, practical and transcendental orders that humanity has prior, autonomous and efficacious powers which it brings to society itself – and which intertwine with those properties of society which make us social beings, without which, it is true, we would certainly not be recognisably human. (Archer Reference Archer2000: 17–18)Footnote 8

At this conceptual level, Archer’s understanding of the human has so far included continuity of consciousness and bodily constitution as core to the human ability to distinguish and interact with different orders of reality (more on this below). The final dimension that needs to be mentioned also connects the pre-social features of homo sapiens as a unique species with the fact that these potentials are fundamentally (though never exclusively) realised in society. Archer describes it as the ability to imagine new social forms:

homo sapiens has an imagination which can succeed in over-reaching their animal status … human beings have the unique potential to conceive of new social forms. Because of this, society can never be held to shape them entirely since the very shaping of society itself is due to them being the kind of beings who can envisage their own social forms.

Archer’s formulation of the principle of humanity comes to completion, then, as she includes the ability to imagine and devise new social forms. This is a critical agential mechanism of social change, what she refers to as morphogenesis, because new social situations also change the conditions within which autonomous human powers are to be exercised. This is the basis for the key process of dual morphogenesis: it is not only the fact that agents can (imperfectly and only to a degree) modify social structures but that agents themselves change as part of that same morphogenetic process (Reference Archer2000: 258–67, 283–7).

If this is the case, we can now unpack the normative consequences that are built into these conceptual and methodological arguments for a universalistic principle of humanity. This is of course not new; it has been my contention throughout this book that a universalistic principle of humanity is not only a cognitive requirement for sociology to work but that it also has normative implications. To be sure, whether and how we decide to unpack these, and then integrate them into our social scientific work, is an open question that can only be answered by practitioners themselves. Depending on how social scientists understand their tasks as social scientists, they may or may not seek to spell out the normative consequences of their work. But this does not change the fact that, to the extent that social scientific propositions operate within an implicit principle of humanity, there are normative implications that do follow from our conceptual and methodological commitments: these planes need to be clearly distinguished but we cannot, I contend, fully or definitively separate them out. Even if we decide not to engage with them, there are normative implications that simply do not go away. Archer does spell out the normative implications of her methodological and conceptual commitments and, given that she seeks to establish the autonomy of humanity vis-à-vis society, this normative dimension is an integral part of her sociological programme:

since it is our membership of human species which endows us with various potentials, whose development is indeed socially contingent, it is therefore their very pre-existence which allows us to judge whether social conditions are dehumanizing or not. Without this reference point in basic human needs … then justification could be found for any and all political arrangements, including ones which place some groups beyond the pale of “humanity”. Instead, what is distinctively human about our potentialities impose certain constraints on what we can become in society, that is, without detriment to our personhood.

The task of promoting or indeed working politically towards the realisation of institutions that favour this type principle is not one that is only or indeed specifically incumbent on the sociologist on her expert role: its appeal surely falls outside of what defines the practices of the social scientist as a social scientist. And yet the argument that I am making through Archer’s reflections is that there are direct normative implications of carrying out sociological work. On the grounds of its universalistic principle of humanity, sociology is in a position to explain the rise of various social institutions and then unpack its humanising or dehumanising effects on the development of integral human personhood. The normative grounds on which judgements are being made depend directly on whether or not the pre-social contributions of our shared humanity to social life are being protected, promoted, affected or irreparably damaged.Footnote 9

Archer rehearses a similar argument in different ways, but one that is particularly illustrative focuses on the consequences of withdrawing all autonomy to humanity and conceiving it instead as a gift of society. The main problem with this position, which is shared by a wide range of sociological imperialists, postmodernists and indeed social constructionists, is that it leaves us with no solid ground on which to defend or criticise different social institutions: ‘[t]here can be no inalienable rights to human status where humanity is held to be a derivative social gift’ (Reference Archer2000: 124). This is not altogether different from the argument that, in the Introduction, I raised against some versions of posthumanism: they cannot develop a critical theory that cares deeply about social injustices but then makes that caring creature fully dependent on society itself: ‘if resistance is to have a locus, then it needs to be predicated upon a self which has been violated, knows it and can do something about it’ (Reference Archer2000: 32). In a formulation that may partly resonate with those of Boltanski in Chapter 8, the consequences of being unable to capture conceptually the autonomy of our humanity vis-à-vis sociality may be felt most clearly at a normative level; that is, it is expressed in the ways we justify the obligations towards those who, for whatever reason, are in weaker or more vulnerable positions in society:

there is something very worrying about a social approach to personhood which serves to withhold the title until later in life by making it dependent upon the acquisition of social skills. This fundamentally throws into question our moral obligations towards those who never achieve speech (or lose it) or who can never relate socially, because, having failed to qualify as persons, what precludes the presumption that they lack consciousness of how they are treated (thus justifying the nullification of our obligations towards them)?

Archer’s universalistic principle of humanity works as the key counterfactual that makes possible our understanding of life in society: social life presupposes the fundamental equality of human beings, who are all equally equipped for the creation and recreation of social life. It is this fundamental equality that gives normative purchase to the claim that it matters so much that we do not choose, nor can we alter at will, the highly unequal social conditions under which we exercise our human capabilities. But for this argument to work, it remains central that we see how this universalistic orientation works simultaneously in three planes: conceptually, all human beings are equally able to create and recreate social life; methodologically, social scientific knowledge is susceptible of translation across different cultural and historical contexts, and; normatively, we are able to assess different social and institutional practices as either favouring or undermining those fundamental qualities that are constitutive of our shared humanity. The principle of humanity is the condition of possibility of sociological knowledge – it is sociology’s own regulative idea (Chernilo Reference Chernilo2007a).

II

Archer’s opening claim in Being Human is precisely the defensive statement that we ought to ‘reclaim Humanity which is indeed at risk’ (Reference Archer2000: 2). Building on her critique of upward, downward and central conflation, a primary goal of that project was to resist equally wholly individualistic definitions that reduce our humanity to hedonistic motives and constructivist positions that define humanity exclusively through our symbolic interactions with the social world. Her positive starting point is, as we have seen, the claim on the bodily grounding of our continuous sense of self as this offers a pre-social justification for the autonomy of our humanity. We also briefly mentioned that she sees humans as living in a world that is differentiated in three main orders: the natural, the practical and the social orders. If we now briefly explain each one of them, we see that our physical well-being depends on our relationships with the natural order; our performative achievements depend on our mastery of objects in the practical order and our notions of self-worth are constituted through interactions in the social order (Reference Archer2000: 9).Footnote 10 Archer contends that, as humans, we require all three orders and, crucially, that there is no automatic or necessary harmony in the ways in which we interact with them. The predicament of the human condition requires us to pay attention to all orders simultaneously, to realise that there is continuous intercommunication between them, but also to accept that there can be no guarantee that they shall ‘dovetail harmoniously’ (Reference Archer2000: 220). The notion of modus vivendi on which our personal identity coheres refers to our simultaneous yet complicated relationships with all three orders.Footnote 11

In relation to the natural world, the key human challenge lies of course in our physical adaptation to it, which includes also our human attempts at its modification. Archer connects this dimension to Marx’s critical insight of the human need for ‘continuous practical activity in a material world’ (Reference Archer2000: 122).Footnote 12 Crucially, the partial independence between human powers and social structures is another expression of the fact that meeting our physical and organic requirements in our relations with the natural world may well depend on society’s institutions but is not something for society alone: physical ‘survival cannot delay practical action in the environment until the linguistic concept of the self (as “I”) has been acquired’ (Reference Archer2000: 123).

The second domain of practice is in fact the central in Archer’s argument. Here, the primary dimension is that of our interactions with objects that then constitute the platform for our performative achievements. Thus understood, practice is primarily non-discursive and, even more importantly, she contends that practice has ‘primacy’ and is indeed ‘pivotal to all our knowledge’ (Reference Archer2000: 152). As members of the human species, practical accomplishments in our relations with objects and non-human creatures are the ones that fundamentally shape who we become: ‘our human relations with things (animate and inanimate, natural and artificial), help us to make us what we are as persons’ (Reference Archer2000: 161). In this domain, moreover, our human uniqueness vis-à-vis animals remains more a matter of degree than of quality, and this includes also ‘our tendency to enhance or extend our embodied knowledge by the invention and use of artefacts’ (Reference Archer2000: 161). Not only that, the critical dimension that humans share with animals is that of being able to anticipate the impact that external facts may have on our bodies (Reference Archer2000: 202). One of Archer’s most fundamental arguments is also found here, as she contends that these accomplishments in the practical order are ‘intrinsically non-linguistic’ (Reference Archer2000: 160). Recurrent usage of such expressions as the need to develop ‘a feel for the game’ is, in her view, a way of accepting the fact that practical accomplishments cannot be ‘easily or fully expressed in words’ (Reference Archer2000: 160). Practical consciousness and above all performative accomplishments in our bodily relationships with the elements (swimming in the case of water, jumping in the case of gravitational pull), with objects (aptly using a sharp knife, driving a car at speed) and with non-human beings (our relationships with animals and indeed technology) all fall within this category. The fact that most of them can only be performed within a wholly social setting does not for her alter the fact that these are non-discursive practices and accomplishments: ‘practical consciousness represents that inarticulate but fundamental attunement to things, which is our being-in-the-world’ (Reference Archer2000: 132). To affirm the primacy of practice over language is another argument against the notion that the latter offers an adequate definition of the human. In turn, this offers additional grounds to her rejection of the conventional proposition that, in modern science, epistemology is prior to ontology. Archer reverses this relationship precisely on the grounds of the primacy of practice over the social bonds of language:

the argument that “practice is pivotal” has, as its basic implication, that what is central to human beings are not “meanings” but “doings” … it is in and through practice that many of our human potentia are realised, potentials whose realisation are themselves indispensable to the subsequent emergence of those “higher” strata, the individual with strict personal identity … it has been argued here that a human being who is capable of hermeneutics has first to learn a good deal about himself, about the world, and about the relations between them, all of which is accomplished through praxis. In short, the human being is both logically and ontologically prior to the social being, whose subsequent properties and powers need to be built upon human ones.

Archer’s argument on the final domain, the social world, includes human interactions between people, people’s ability to create and interpret various cultural artefacts, and the results of aggregated action that give rise to social agents and actors (Reference Archer1995: 247–93; Reference Archer2012: 173). It is on this basis that Archer makes the case that our personal identity is wider than our strictly social identity, on the one hand, and that the positions we occupy as social actors involve an active commitment to the achievement of certain goals, on the other. This kind of active interest is lacking in the more passive social positions we occupy as agents (Reference Archer2000: 253–4).Footnote 13

Although they are never mentioned explicitly, we recognise here some of the foundational themes of early philosophical anthropology; crucially, the notion that the human body is both a physical presence in the world and the condition of possibility of our experiencing the world: ‘[o]bjects are before me in the world, but the body is constantly with me, and it is my self-manipulation, through mobility and change of point of view, which can disclose more of the object world to me’ (Reference Archer2000: 130). The natural and the practical orders are therefore both fundamentally related to the bodily constitution of our humanity: the satisfaction of our needs, on the one hand, and our mastery of various subject/object relations, on the other. These two may of course overlap, but need to be distinguished. This is again an argument in support of the claim that our ability to treat other humans as members of our species, and then understand social facts as ultimately the result of human interaction, is already built into our shared humanity: ‘our practical work in the world does not and cannot await social instruction, but depends upon a learning process through which the continuous sense of self emerges’ (Reference Archer2000: 122). Human fundamentals such as the intuitive grasp of causal action and the basic laws of logic are dependent upon this same universal sense of embodiment: ‘[t]he basic laws of logic are learned through relations with natural objects: they cannot be taught in social relations, since the linguistic medium of socialisation presupposes them’ (Reference Archer2000: 126, my italics). The fundamental distinction between social and non-social objects is in itself one contribution of our humanity to society:

Each one of us has to follow the same personal trajectory of discovering, through private practice and by virtue of our common human embodiment, the distinction between self and otherness and then that between subject and object, before finally arriving at the distinction between the self and other people – which only then can begin to be expressed in language. These discoveries are made by each and every human being and their disclosure is independent of our sociality: on the contrary, our becoming social beings depends upon these discoveries having been made.

Archer is advancing what she calls a ‘stratified view of humanity’, where the different strata are emergent and irreducible to one another. Thus seen, she says, it is not only that social structures, culture and humans are strata, but human beings themselves are ‘constituted by a variety of strata … schematically, mind is emergent from neurological matter, consciousness from mind, selfhood from consciousness, personal identity from selfhood, and social agency from personal identity’ (Reference Archer2000: 87). For our purposes, there are four main strata that matter the most: self, person, agent and actor. The argument again reinforces her proposition that an idea of the self is the key dimensions of our humanity that remain pre-social: ‘[a]s adult human beings, we are three-in-one – persons, agents and actors – but we never lose our genesis in the continuous sense of self which is formed non-discursively through our practical action in the world’ (Reference Archer2000: 153). Personal identity is complete in adulthood because only then have people developed a fuller and more stable set of relations with the three orders of reality we have discussed so far: the natural, the practical, and the social. It thus follows that these will determine where our ‘ultimate concerns lay and how others were to be accommodated to them’ (Reference Archer2000: 257). The emergence of full personal identity is a social accomplishment in a way that our sense of self is not. Yet because it entails the simultaneous incorporation of the three orders, personal identity remains wider and deeper than any notion of social identity: ‘[S]ocial identity is only assumed in society: personal identity regulates the subject’s relations with reality as a whole. Therefore, of the two emergent human properties, the self stands as the alpha of social life, whilst the person is its omega’ (Reference Archer2000: 257). Agents and actors are then exclusively social in a way that the self and the person are not and, because of that, agents and actors are themselves dependent on self and personhood. Agents and actors are collective instantiations of our humanity, but their main difference is that the former connotes the passive position people occupy in society (gender, age, nationality, for instance), whereas the latter involves active engagement and setting of goals to be achieved (we are students, football fans, union members, etc.).

A major theoretical implication is to be drawn from our discussion thus far: for all her concerns with what is specific about our humanity, Archer’s argument is explicitly built as a critique of anthropocentrism. Let me unpack this argument in the following three steps:

1. The human reliance on the body for the realm of practice brings us closer to rather than further away from animals: this basic domain of human experience is not specifically human and thus allows the whole argument to take a critical distance from anthropocentrism. As we saw already, animal species cannot enhance their experience through the use of tools to the extent that humans do, but this is ultimately a matter of degree (Reference Archer2000: 111).

2. Ontogenetically, we have seen that the ability to distinguish the social world as an autonomous domain, and to manipulate social objects within it, is not concomitant with birth; it instead only appears in early childhood. As we learn, for instance, that the laws of nature apply in general and are not subject to our control, we also learn that an adequate understanding of the social world equally implies the rejection of an anthropocentric outlook: neither everything that occurs in society centres on my needs, desires and feelings nor can I fully control the actions of others. This, Archer calls the very ‘foundations of nonanthropocentric thought’ (Reference Archer2000: 146). She expands on it as follows:

it is only as embodied human beings that we experience the world and ourselves … and thus can never be set apart from the way the world is and the way we are … Those who only accentuate us in our necessarily limited, because embodied, nature then endorse anthropocentrism – a world made in our image and thus bounded by our human limitations, as in pragmatism or critical empiricism …. Yet, the affordances of human experience describe our point of contact with reality; but they neither exhaust reality itself, nor what can be discovered about it. Our “Copernican” discoveries exceed and often run counter to the information supplied by our embodied senses.

3. Through its critique of both religion and traditional metaphysics, the modern scientific and philosophical imagination gives a new lease of life to an anthropocentric perspective: anthropocentrism reappears ‘with a vengeance’ when humans replace god in its self-determining and apparently omniscient powers (Reference Archer2000: 21–3). Archer then contends that little has in fact been gained here because what started as a critique of foundationalism ends up in an unacceptable kind of perspectivism: it all depends on how humans claim things to be (Reference Archer2000: 45). The ‘charitable humanism’ that underpins this position is mistaken because what the world is does not depend on how humans think it to be (Reference Archer2000: 21).Footnote 16 An additional normative consequence of this inflated anthropocentrism is that it creates the condition for social constructionism and its view that humanity is a social product and it is, above all, linguistically formed. As we have seen, Archer rejects any anthropology that builds on the idea of homo significans because no autonomous idea of humanity can be built on its premises. (Reference Archer2000: 24–5)

Archer’s rejection of anthropocentrism then offers two different lines of argument. In the first, her ideas on the importance of the natural and practical orders are referred back to the development of the natural sciences in the modern world. It is true that modern science affords humans with a sense of wonder about our own omnipotence – we can play god if we so wish – but the more salient implication in her view is that, because human life depends on domains that it neither produces nor fully controls, the scientific imagination remains, first and foremost, a rejection of any strong anthropocentrism.Footnote 17 The second argument against anthropocentrism also goes back to the ontological fallacy of mistaking our representations of the world for what the world actually is: ‘[c]onflating worth with being can only result in anthropocentrism because it elevates our epistemic judgements over the ontological worth of their objects’ (Reference Archer2000: 225). Archer’s realism is a critique of anthropocentrism because the latter, instead of actually helping in making a persuasive claim on the fact that ‘people matter’, ultimately depends on the ‘strident doctrine that nothing matters at all except in so far as it matters to man’ (Reference Archer2000: 23). In its ultimate subjectivism, we may even say that nothing matters at all unless it matters to me. The wider implications of her critique are worth looking at in detail. In Archer’s own words:

Anthropocentrism binds us intransigently to indexicals even though it wants these to be as big as the human race. But often it is not the case that humanity shares a universal language which is accepted as necessary in order to make sense of experience, and even if we do we might be wrong because the game we are playing might be that of global actualism. Thus knowledge from a universal human perspective may only represent globalised fallibility. After all this is what Enlightenment thinkers held the pervasive religious language of the antecedent period to be: it is also how postmodernism reflects upon the generalisation of the Enlightenment project itself in the language of Modernity.

While I follow Archer in her commitment to the universalistic underpinnings of a principle of humanity, I take a more positive stance towards the possibilities that are opened by this ‘global actualism’: this is precisely what current globalisation processes open up with the possibilities of a more cosmopolitan outlook (Chernilo Reference Chernilo, Krossa and Robertson2012b). Here, however, it is important to make it clear that this is not to do with possible Eurocentric implications or presuppositions of her argument.Footnote 18 In fact, Archer (Reference Archer1991) had early on made a convincing programmatic statement on these questions in the context of her presidential address to the International Sociological Association. On the one hand, and this is a statement whose strictly empirical validity is surely a matter of contention, she has recently argued that the conditions of accelerated social change that she described as the rise of the morphogenetic society have not fully reached ‘the south’ (Reference Archer2012: 17). The argument is plausible, it seems to me, if it means that there are pockets of people who feel the effects but are not in a position to actively engage with the contemporary conditions of global modernity: otherwise, in terms of the sheer number of people being affected by globalisation, poorer parts of the world have arguably witnessed more rather than less changes than wealthier regions. More importantly, on the other hand, Archer herself had offered a more nuanced account of the relationships between a universalistic principle of humanity and current global modernity: ‘[f]or the first time ever, there are pressures upon everyone to become increasingly reflexive, to deliberate about themselves in relation to their circumstances; not freely, because unequal resource distribution, life chances and access to information have intensified dramatically on a world scale, but nevertheless self-consciously, given the demise of collective agencies shouldering the burden for them’ (Reference Archer2007: 53).

We need to ask, however, whether the strong rejection of anthropocentrism that has been put forward – as condition of possibility of our practical occupancy in the world – comes with a concession to a soft version of it: human embodiment as a restriction to the ability of self-transcendence that we discussed in Chapter 2. To a large extent, some of the main themes in the posthumanist literature depend on some version of this argument: humanism and anthropocentricism are built on the pretence that humans can never step outside their embodiment. But this is a chain of thought that Archer explicitly rejects because for posthumanists human embodiment is all that there is. The more pressing question then becomes whether we are able to use this embodiment as a resource that also works towards its transcendence. Archer’s argument on human reflexivity, it seems to me, allows her precisely to do this.

III

The proposition that reflexivity defines how humans exercise their autonomous powers in society was first introduced in Being Human; for instance in reference to Marcel Mauss’s argument on the concept of the self. More recently, in The Reflexive Imperative in Late Modernity, Archer looks back at this initial interest in reflexivity as something that was not intrinsically related to the study of ‘human subjectivity’, but which rather ‘began from seeking to answer the theoretical question about how structure and culture got in our personal acts’ (Reference Archer2012: 294). Understanding reflexivity has then to do with the delimitation of those defining powers of agency that are irreducible to cultural and structural properties. Thus conceived, reflexivity becomes ‘a personal property of human subjects, which is prior to, relatively autonomous from and possesses causal efficacy in relation to structural or cultural properties … “reflexivity” is put forward as the answer to how “the causal power of social forms is mediated through human agency”’ (Reference Archer2007: 15).

Self-sufficient, autonomous and causally efficacious, reflexivity is expressed in our internal conversations: ‘[r]eflexivity is exercised through people holding internal conversations’ (Reference Archer2007: 63). Reflexivity is fundamentally exploratory and transforms, reorients and prioritises our personal concerns into the projects that we seek to realise in society. Reflexivity usually adopts the form of question and answers that take place inside our heads and, because it is oriented to objects (including our own physical embodiment) it has a fundamentally practical intent: ‘reflexivity is the regular exercise of the mental ability, shared by all normal people, to consider themselves in relation to their (social) contexts and vice versa’ (Reference Archer2007: 4). Reflexivity is internal but refers to things that take place in the world; only external objects and events can trigger the autonomous exercise of human reflexivity. This connection with the world also allows Archer to contend that the internal conversation is not a form of solipsism or mere introspection: ‘human interaction with the world constitutes the transcendental condition of human development’ (Reference Archer2000: 17; see also Reference Archer2000: 315; Reference Archer2012: 11). Language plays a major role in the way this is actually achieved as language becomes the interface between ‘the inner’ and ‘the outer’:

the private and innovative use made of the public linguistic medium is just as significant as the fact that natural language is an indispensable tool for the emergence of the private inner world in the first place. As the home of the internal conversation, the inner world is a domain of privacy fabricated from public materials; as a “plastic theatre” of inner drama, it is dependent upon my imaginative construction and use and is thus a first-person world; as the bearer of causal powers, its exercise can modify both us ourselves and our social environment.

For reflexivity to be treated as a genuine emergent property, it can be determined by neither our personality structure nor social class (Reference Archer2012: 16; Reference Archer2007: 96–7). If not an idea of human nature as such, Archer accepts that at stake here is the definition of our major anthropological markers as a species: reflexivity is to be found throughout all human cultures (Reference Archer2012: 2) and she goes as far as to define it the ‘transcendental condition of the possibility of any society and one for which empirical evidence can be adduced’ (Reference Archer2007: 29). Equally importantly, from the point of view of its practical purchase for social research, Archer contends that our human abilities and skills work through the medium of reflexivity: it is through the practical deployment of various kinds of reflexivity that humans make their way through the world. Reflexivity matters because none of the big ‘questions about the nature of human action in society is answerable without serious reference being made to people’s reflexivity … Human beings are distinctive not as the bearer of projects, which is a characteristic people share with every animal, but because of their reflexive ability to design (and redesign) many of the projects they pursue’ (Reference Archer2007: 5 and 7, my italics).

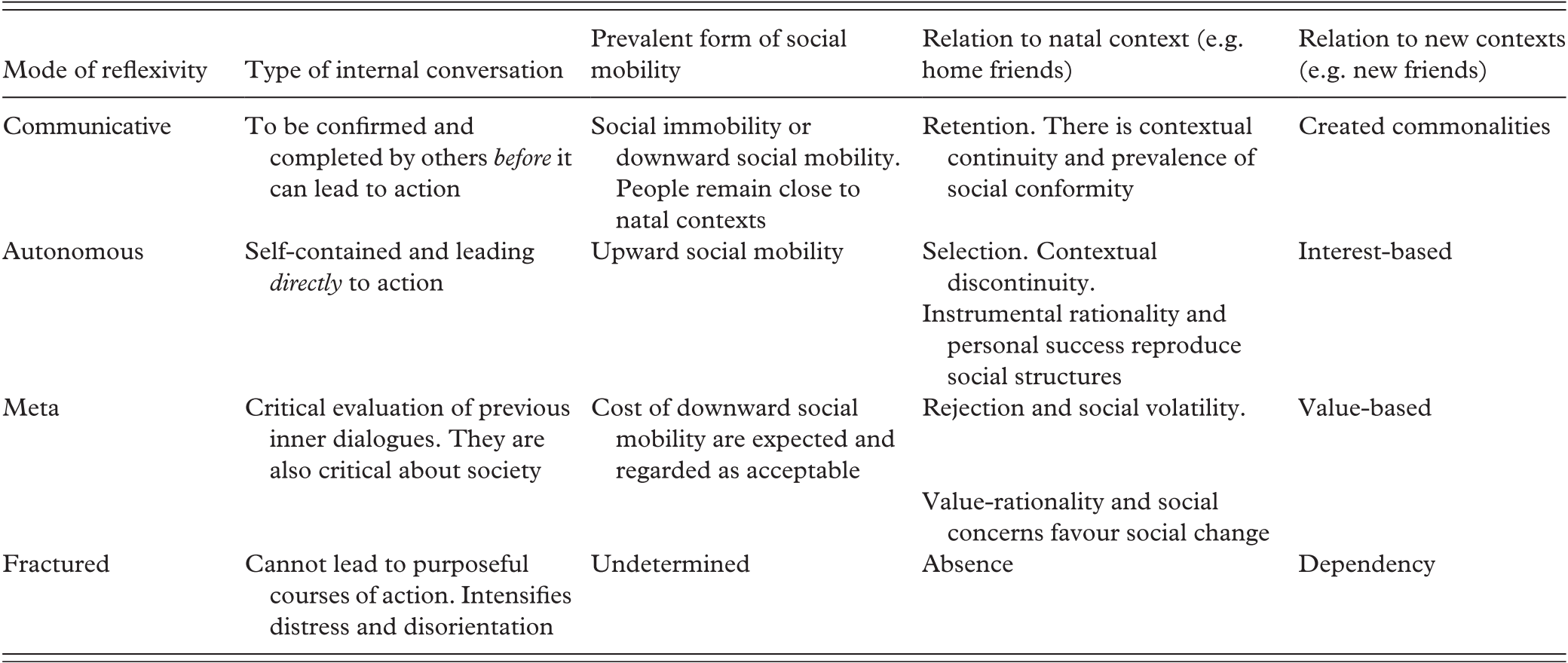

Sociologists have so far not paid enough attention to the workings of reflexivity and yet, when they have, they mistake it for a property of social systems. Sociology, Archer contends, has failed to give an account of one of the most fundamental mechanisms through which life in society takes place: ‘no reflexivity: no society’ (Reference Archer2007: 15; Reference Archer2012: 2). In the case of contemporary sociology, the two main writers against which she makes this case of the neglect of reflexivity are Pierre Bourdieu and Ulrich Beck. In relation to Bourdieu, Archer argues that the idea of habitus is a paradigmatic case of central conflation; that is, structure and agency are elided rather than remain analytically distinct. At the same time, as habitus emphasises our pre-conscious and habitual routines of action, it remains fundamentally at odds with the ability of people to take control over their own actions. This static feature of habitus makes Bourdieu unable to explain social change and this goes against the general morphogenetic impetus of Archer’s work (Reference Archer2007: 38–55).Footnote 19 In relation to Beck, Archer accepts his thesis that there is a decline in traditional actions and routines but she then criticises him on two different grounds. First, because Beck sees reflexivity only as a societal process rather than as the property of agents; even Beck’s notion of individualisation is something that occurs, to a large extent, at the back of individuals themselves. Second, Archer’s reflexivity involves the reconfiguration rather than the weakening of social structures (Reference Archer2007: 3–4, 29–37, 55). Increasingly, however, reflexivity has become itself an epochal diagnosis in Archer’s work. Modern societies as such are marked by contextual discontinuity; structural changes and lack of synchronicity between structural and cultural transformations make for enhanced reflexivity a key marker of modernity itself (Reference Archer2012: 23–6). What we witness over the past three or so decades is, therefore, that ‘the extensiveness with which reflexivity is practised by social subjects increases proportionate to the degree to which both structural and cultural morphogenesis (as opposed to morphostasis) impinge upon them’ (Reference Archer2012: 7). As we see in Table 7.1, in contexts of accelerated social change autonomous reflexivity becomes the most distinctive one in global modernity. The key fact that social scientists are missing here is that human reflexivity is not applied homogeneously throughout society. There is no one single way of being reflexive but, on the contrary, different modes ‘that are differently dependent upon internal conversation being shared in external conversation’ (Reference Archer2007: 84). Archer develops a fourfold typology of communicative, autonomous, meta- and fractured reflexivity, which obtains from the qualitative and quantitative empirical studies that make up the bulk of her writing of the past fifteen years (Reference Archer2003, Reference Archer2007, Reference Archer2012).

| Mode of reflexivity | Type of internal conversation | Prevalent form of social mobility | Relation to natal context (e.g. home friends) | Relation to new contexts (e.g. new friends) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicative | To be confirmed and completed by others before it can lead to action | Social immobility or downward social mobility. People remain close to natal contexts | Retention. There is contextual continuity and prevalence of social conformity | Created commonalities |

| Autonomous | Self-contained and leading directly to action | Upward social mobility | Selection. Contextual discontinuity. | Interest-based |

| Instrumental rationality and personal success reproduce social structures | ||||

| Meta | Critical evaluation of previous inner dialogues. They are also critical about society | Costs of downward social mobility are expected and regarded as acceptable | Rejection and social volatility. | Value-based |

| Value-rationality and social concerns favour social change | ||||

| Fractured | Cannot lead to purposeful courses of action. Intensifies distress and disorientation | Undetermined | Absence | Dependency |

See also Caetano (Reference Caetano2015) for further discussion.

This differentiated exercise of reflexivity matters because it is constitutive of who we are as unique individuals. Moreover, while human relations to the natural and the practical environments may not be primarily reflexive, their continuation as a project, as a concern whose accomplishment matters to us, is informed by socially mediated reflexivity.Footnote 20 As elaborate commentary, emotions fundamentally regulate our relations with the world (Reference Archer2000: 204). Archer then expands on the idea of emotions in order to emphasise how humans relate to the the social, the practical and the social worlds. It is thanks to the internal conversation that ‘our first-order emotionality is reflexively transformed into second-order emotional commentary’ (Reference Archer2000: 221). As we mentioned them above, the key emotion for the natural world is that of physical well-being, for the practical order it refers to such experiences of frustration, boredom, satisfaction or even euphoria in the ways we accomplish things and, with regard to society, self-worth is our prime concern (Reference Archer2000: 212–15). If emotions have traditionally been seen as irrational, this is not because of some intrinsic feature that precludes them from systematic consideration but because they refer to things that concern us deeply: emotions are linguistically articulated and passionate accounts about what is going on in the world – and, to that extent, they are anthropocentric. But because we are fallible beings, this same anthropocentrism may backfire and become wholly counter-functional (Reference Archer2000: 207–8). Emotions refer to all domains of reality, so Archer rejects the idea that there is any such thing as a basic emotion: emotions come in clusters that require prioritisation and this is an active task that is only performed by humans themselves through their internal conversations (Reference Archer2000: 199–200).

Because it is conceptualised as independent vis-à-vis social and cultural structures, it is not always clear whether reflexivity applies only to human relationships to the social world or, instead, it applies also to human interactions with the natural and practical world. If the former, the argument emphasises the fact that no form of human activity takes place wholly outside a social environment: culture and society are the artificial environment that surrounds everything human. If the latter, however, the argument would have to be that even those activities that deal, for instance, with organic adaptation (breathing) may become the object of reflexive monitoring whether or not they have primary social causes (catching a cold). Our actions to change that organic state are indeed social (visiting a doctor, taking medicine, etc.) but need to have an adequate correlate with the intransitive properties of nature herself. Archer argues that emotions work through commentary about our concerns in the internal conversation and also that reflexivity refers primarily, indeed almost exclusively, to our relations with the social world. The methodological purchase of both arguments is clear, as it allows for greater precision in looking at emotions and reflexivity in a manner that is susceptible of empirical sociological research. This move appears to create complications for her argument on the autonomy and emergence of our humanity vis-à-vis society, however: if emotions are to be seen, fundamentally, as linguistic articulations of our concerns, then we can hardly have emotions that have not gone through some form of social shaping. Similarly, if reflexivity refers primarily to our concerns in the social world, then it is not clear how or why can reflexivity remain immune from social influences throughout one’s life and does not become derivative, say, from class socialisation or liminal experiences of success or failure. This matters because at stake here is the claim that reflexivity is the defining anthropological features of an autonomous idea of the human.

Archer’s idea of ultimate concerns is another way of advancing a critique of utilitarianism and instrumental rationality as the only or at least major drive of individual psychology (Archer and Tritter Reference Archer and Tritter2000). Rather than being primarily selfish, hedonistic or self-centred, humans have, on the contrary, a fundamental ‘capacity to transcend instrumental rationality and to have “ultimate concerns”’ (Reference Archer2000: 4). And it is through this focus on ultimate concerns that she elaborates further the positive content of her anthropology in terms of a substantive definition of what makes us human beings: ‘we are who we are because of what we care about: in delineating our ultimate concerns and accommodating our subordinate ones, we also define ourselves’ (Reference Archer2000: 10). For emotions to emerge, we have to care about the evaluations that are at stake: ‘[i]t is we human beings who determine our priorities and define our personal identities in terms of what we care about. Therefore we are quintessentially evaluative beings … the natural attitude of being human in the world is fundamentally evaluative’ (Reference Archer2000: 318–19). A human is a being who cares.Footnote 21

There is indeed a resemblance here to some of the ideas we discussed in Chapter 6 on Charles Taylor’s conception of strong evaluations and moral goods. Taylor’s argument on ‘transvaluation’ is of relevance to Archer because it makes clear that emotional complexity is in fact normal occurrence: we learn to deal with a constellation of emotions that only become apparent through our internally running commentaries: emotions are plural because ultimate concerns are themselves plural (Reference Archer2000: 226). Prioritisation and then accommodation of concerns gives rise to one’s modus vivendi that is, again, personal. This is what the internal conversation does: ‘the goal of defining and ordering our concerns, through what is effectively a life-long internal conversation, is to arrive at a satisfying and sustainable modus vivendi’ (Reference Archer2007: 87). But at the same time that she offers a similar argument to Taylor’s, Archer is too much of a sociologist to accept the normativism of Taylor’s position. She then speaks of relational goods and relational evils in a way that directly contravenes Taylor’s insistence on our attachment to the good: people engage in harmful and indeed self-destructive behaviour that becomes constitutive to what they are – there is not automatic association between self and good (Reference Archer2012: 99, 257–8).Footnote 22 A personal modus vivendi does offer a sense of unity and, to that extent at least, it may operate as the kind of hypergood that Taylor rejects – although in this case this is a practical accomplishment of people themselves rather than the imposition of professional philosophers. It is the fact that we become able to deal with the various and simultaneous challenges of life in a way that is satisfactory for us that constitutes the condition of possibility of the good life. This is, to be sure, too weak a normative argument for Taylor, for whom ultimate concerns are necessarily high and lofty rather than, say, looking after one’s allotment.Footnote 23

Archer sides with Taylor against the Kantian notion that proceduralism is the right approach to deal with normative questions. Modern proceduralism fails because it presupposes two notions that she rejects: first, that there is a unity or at least clearly a hierarchy of goods that can be univocally preferred and be turned into a meta-rule; second, sound moral reasoning is not dispassionate but emotional in relation to things we care deeply about (Reference Archer2012: 112–13). I have already argued that I give greater importance to moral proceduralism as a way of trying to make sense about the complexities of social life. Archer is surely right when she says that we experience conflicts among our various concerns in a way that does not accommodate to a standard model of trying to generalise one’s own maxims of action. But the fact that moral proceduralism is unable to solve all normative conflicts does not mean that it can be of little or no use as we make decisions about various domains of life – including, above all our fundamental moral intuitions about justice and fairness in society. I have argued above that, ever since Kant’s formulation of the categorical imperative of morality, there is a limitation in this mode of reasoning because it does not lend itself to making decisions among competing general claims: e.g., justice versus liberty. But, at the same time, it is this kind of categorical imperative that opens itself to the claim to universalism that underpins Archer’s own principle of humanity. Differently put, there can be no ultimate idea of relational goods and evils without the possibility of us linking our personal decisions and concerns to that which may be the right course of action for the species as a whole. Will this always and unequivocally offer sound moral guidance? Surely not, but even in this weakened sense it remains a key dimension of our normative imagination.