Book contents

- The Cambridge History of Communism

- The Cambridge History of Communism

- Endgames? Late Communism in Global Perspective, 1968 to the Present

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Plates

- Figures

- Contributors to Volume III

- Introduction to Volume III

- Part I Globalism and Crisis

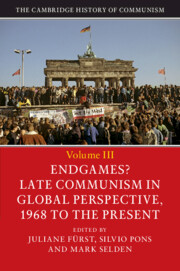

- Part II Everyday Socialism and Lived Experiences

- Part III Transformations and Legacies

- Index

- Plate Section

- References

Part II - Everyday Socialism and Lived Experiences

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 September 2017

- The Cambridge History of Communism

- The Cambridge History of Communism

- Endgames? Late Communism in Global Perspective, 1968 to the Present

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Plates

- Figures

- Contributors to Volume III

- Introduction to Volume III

- Part I Globalism and Crisis

- Part II Everyday Socialism and Lived Experiences

- Part III Transformations and Legacies

- Index

- Plate Section

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge History of Communism , pp. 279 - 446Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017

References

Bibliographical Essay

In recent years, historical scholarship on post-Stalinist society has been in full bloom. Compared to the Stalin years, however, it is still underresearched and relies heavily on memoirs and autobiographies.

The era began with one of Khrushchev’s cardinal achievements: the emptying of the Gulag, which is the topic of Dobson, Miriam’s Khrushchev’s Cold Summer: Gulag Returnees, Crime, and the Fate of Reform after Stalin (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009). Barenberg, Alan describes the transformation of Vorkuta from camp to factory town after Stalin’s death in Gulag Town, Company Town: Forced Labor and Its Legacy in Vorkuta (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), highlighting one of the many structural consequences of the end of terror. Perhaps no topic in the 1950s and 1960s has received more attention than the intelligentsia and the Thaw, particularly official and popular efforts to make sense of Stalinism. Kozlov, Denis’s The Readers of Novyi Mir: Coming to Terms with the Stalinist Past (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), Bittner, Stephen V.’s The Many Lives of Khrushchev’s Thaw: Experience and Memory in Moscow’s Arbat (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008), Jones, Polly’s Myth, Memory, Trauma: Rethinking the Stalinist Past in the Soviet Union, 1953–1970 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013) and many of the essays in Kozlov, Denis and Gilburd, Eleonory’s The Thaw: Soviet Society and Culture in the 1950s and 1960s (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013) deal with important aspects of this question. An interesting exploration of the world of the 1960s intellectual from within can be found in Vail, Petr’ and Genis, Aleksandr, Mir sovetskogo cheloveka 60-e [The World of the Soviet Man of the 1960s] (Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2001). Khakhordin, Oleg’s The Collective and the Individual in Russia: A Study in Practices (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999) asks similar questions and forms part of a number of scholarly attempts to draw parallels between the pre- and post-Stalinist periods. Official efforts after Stalin’s death to bolster living standards and consumption in the context of the Cold War, and popular responses to them, are the topic of a number of seminal essays by Reid, Susan E.. Especially notable is “Cold War in the Kitchen: Gender and the De-Stalinization of Consumer Taste in the Soviet Union Under Khrushchev,” Slavic Review 61, 2 (Summer 2001), 212–52. Housing, the focus of the greatest investment and arguably the most life-changing project for the average Soviet citizen, is the central concern in Harris, Steven E.’s Communism on Tomorrow Street: Mass Housing and Everyday Life After Stalin (Washington, DC, and Baltimore: Woodrow Wilson Center Press and Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012) and Varga-Harris, Christine’s Stories of House and Home: Soviet Apartment Life During the Khrushchev Years (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015).

Soviet society in the Brezhnev years is less well documented, even though it should be noted that there is an extraordinary amount of work in progress. Raleigh, Donald’s Soviet Baby Boomers: An Oral History of Russia’s Cold War Generation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011) follows a cohort of so-called shestidesiatniki into the “stagnation” of the Brezhnev years. The epitaph “stagnation” finds itself under fire, yet not replaced by a more suitable paradigm, by a number of authors who are published in Fainberg, Dina and Kalinovsky, Artemy (eds.), Reconsidering Stagnation in the Brezhnev Era: Ideology and Exchange (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2016). The most influential analysis of the late Soviet citizen comes from Yurchak, Alexei’s Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006). Yurchak’s concentration on those who lived in the liminal space that was part of the Soviet system, as well as outside it, suggests that Soviet “normality” became a highly complex and subjective concept in this period. The thesis of the disintegration of the Soviet “norm” is borne out in works as diverse as Ward, Chris’s study of the Baikal–Amur Mainline railway, Brezhnev’s Folly: The Building of BAM and Late Soviet Socialism (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009) and Jackson, Michael Jesse’s study of the Moscow conceptual group, The Experimental Group: Ilya Kabakov, Moscow Conceptualism, Soviet Avant-Gardes (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010). The borders of late Soviet normality are also investigated in Kozlov, V. A.’s Massovye besporiadki v SSSR pri Khrushcheve i Brezhneve [Mass Riots in the USSR Under Khrushchev and Brezhnev] (Moscow: ROSSPEN, 1999), which explores the state’s response to social unrest after Stalin’s death, as well as in the essays presented in Fürst, Juliane and McLellan, Josie (eds.), Dropping Out of Socialism: The Creation of Alternative Spheres in the Soviet Bloc (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2016), which looks at subcultural and marginal phenomena across the Soviet bloc. There has been a certain reluctance by scholars of this period to draw conclusions about the peculiarities of late Soviet society and its ultimate demise, as noted by Platt, Kevin and Nathans, Benjamin in “Socialist in Form, Indeterminate in Content: The Ins and Outs of Late Soviet Culture,” Ab Imperio 2 (2011), 301–24. Whether it is methodologically improper to interpret late Soviet history backwards, from the vantage point of its collapse in 1991, or whether the historian of this period has indeed a duty to explain as well as chronicle this collapse, remains an open question among scholars of late Soviet society.

Bibliographical Essay

Since the fall of communism there has been an outpouring of writing on the Russian Orthodox Church in the communist period, but most of it is in Russian, and most is cast within the framework of relations between church and state. The works of Pospielovsky, Dimitry are still useful: A History of Marxist-Leninist Atheism and Soviet Antireligious Policies (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1987) and Soviet Antireligious Campaigns and Persecutions (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1988). Post-Soviet studies that seek to look at religion as it was practiced and experienced on the ground have developed apace, but mainly for the 1920s. They include Husband, William, “Godless Communists”: Atheism and Society in Soviet Russia, 1917–1932 (De Kalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2000); Young, Glennys, Power and the Sacred in Revolutionary Russia: Religious Activists in the Village (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997); Coleman, Heather J., Russian Baptists and Spiritual Revolution, 1905–1929 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005); Roslof, Edward E., Red Priests: Renovationism, Russian Orthodoxy and Revolution, 1905–1946 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002); and Peris, Daniel, Storming the Heavens: The Soviet League of the Militant Godless (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998). There is a lively collection of essays in Wanner, Catherine (ed.), State Secularism and Lived Religion in Russia and Ukraine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). Freeze, Gregory L., the leading historian of Russian religion in the West, ranges over the centuries; for the Soviet period see, in particular, his “The Stalinist Assault on the Parish, 1929–1941,” in Hildermeier, Manfred (ed.), Stalinismus vor dem Zweiten Weltkrieg: Neue Wege der Forschung (Munich: Oldenbourg, 1998), 209–32. The postwar period is covered by Chumachenko, T. A., Church and State in Soviet Russia: Russian Orthodoxy from World War II to the Khrushchev Years (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2002), and Anderson, John, Religion, State and Politics in the Soviet Union and the Successor States (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

The historiography on communism and religion in the Eastern bloc has mainly focused on state repression, on the official promotion of “scientific atheism,” on the collaboration of the churches with the state, on the role of religion in fostering political resistance and on the emergence of civil society in Eastern Europe. See Berglund, B. and Porter-Szucs, B. (eds.), Christianity and Modernity in Eastern Europe (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2010); Ramet, Sabrina P., Nihil Obstat: Religion, Politics and Social Change in East-Central Europe and Russia (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998); Weigel, George, The Final Revolution: The Resistance Church and the Collapse of Communism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003); von der Heydt, B., Candles Behind the Wall: Heroes of the Peaceful Revolution That Shattered Communism (London: Mowbray, 1993). Relatively little work has been done on the lived experience of believers, although that is now changing. See Betts, Paul and Smith, S. A. (eds.) Science, Religion and Communism in Cold War Europe (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

There has been interesting recent work on the nature of religion in modern China, represented in Palmer, David A. and Goossaert, Vincent, The Religious Question in Modern China (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), and Katz, Paul R., Religion in China and Its Modern Fate (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2014) (dealing with the period up to 1949). Excellent on the republican period is Nedostup, Rebecca, Superstitious Regimes: Religion and the Politics of Chinese Modernity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010). There is very little work on religion in the Mao era, but some of the many studies of the resurgence of religion in the post-Mao era look backwards. For wide-ranging collections on religion in the reform era, see Ashiwa, Yoshiko and Wank, David. L. (eds.), Making Religion, Making the State: The Politics of Religion in Modern China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), and Yang, Mayfair Mei-Hui (ed.), Chinese Religiosities: Afflictions of Modernity and State Formation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008). For local studies that touch on the Mao era, see DuBois, Thomas D., The Sacred Village: Social Change and Religious Life in North China (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005); Chau, Adam Yuet, Miraculous Response: Doing Popular Religion in Contemporary China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016); Harrison, Henrietta, The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Chinese Catholic Village (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013). A general study of Catholics is Madsen, Richard, China’s Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998); and on new religious movements see Palmer, David A., Qigong Fever: Body, Science and Utopia in China, 1949–1999 (London: Hurst & Co., 2007).

Recent comparative treatments of religion under communism are few, but see Marsh, Christopher, Religion and the State in Russia and China: Suppression, Survival, and Renewal (New York: Continuum International, 2011); Madsen, Richard, “Religion Under Communism,” in Smith, S. A. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Communism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 588–604; and Smith, S. A., “On Not Learning from the Soviet Union: Religious Policy in China, 1949–1965,” Modern China Studies 22, 1 (2015), 70–97.

Bibliographical Essay

Research into the art history and wider visual culture of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union since the 1960s has flourished in recent decades, with a raft of publications dealing with the careers of particular artists and movements, comparative accounts of the region as a whole, as well as research focusing on particular themes that cut across geographical boundaries. The most influential survey of the region remains Piotrowski, Piotr’s In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant-Garde in Eastern Europe, 1945–1989 (London: Reaktion Books, 2009), while the artist-led project East Art Map: Contemporary Art and Eastern Europe (London: Afterall, 2006), initiated by Slovenian group IRWIN, was another wide-ranging attempt to insert the “missing” history of East European art into Western-oriented accounts. Among the many exhibitions that have contributed to the self-definition of East European art of the period, particular mention could be made of those that by focusing on particular issues challenged the predisposition to overpoliticize accounts of the art of the socialist era. These include the pioneering “Body and the East: From 1960s to the Present,” curated by Zdenka Badovinac at Moderna Galeria, Ljubljana, in 1999, and ten years later, the self-reflective “Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe,” curated by Bojana Peijić at MUMOK in Vienna. Recent monographs that likewise deal with neglected aspects of the art history of the period include Welch, Klara Kemp’s Antipolitics in Central European Art: Reticence as Dissidence Under Post-Totalitarian Rule 1956–1989 (London: I. B. Tauris, 2014), Morganová, Pavliná’s Czech Action Art: Happenings, Actions, Events, Land Art, Body Art and Performance Art Behind the Iron Curtain (Prague: Charles University Press, 2014) and Fowkes, Maja’s The Green Bloc: Neo-Avant-Garde Art and Ecology Under Socialism (New York and Budapest: Central European University Press, 2015). Another notable tendency has been to question the starkness of the divide between “official” and “unofficial” art, both by treating Socialist Realism as an artistic movement in its own right rather than as mere propaganda, such as in Bown, Matthew Cullerne’s Socialist Realist Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), and by examining the complex relationship of artists, curators and art historians to the socialist art system, which is the focus of a special issue of Third Text edited by Reuben Fowkes on “Contested Spheres: Actually Existing Artworlds Under Socialism” (forthcoming 2017). The particularities of the mass culture of the Soviet 1980s have been analyzed by Yurchak, Alexei in Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), an account that brings to light both points of convergence and disjuncture with the lived experience of socialism in the rest of the Eastern bloc. Research on the history of Soviet and East European design, architecture, urbanism, fashion and cinema also informs interdisciplinary approaches to the visual culture of socialism, such as Crowley, David and Pavitt, Jane (eds.), Cold War Modern: Design 1945–1970 (London: V&A Publishing, 2008), as well as, with its focus on the modern architecture of non-Russian soviet republics, Ritter, Katharina et al. (eds.), Soviet Modernism 1955–1991 (Vienna: Architekturzentrum Wien, 2012), while Ronduda, Łukasz and Zeyfang, Florian (eds.), 1,2,3 … Avant-Gardes: Film/Art Between Experiment and Archive (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2007), have investigated the overlaps between experimental film and the visual arts.

Bibliographical Essay

The best all-round study of the Soviet media industry is Roth-Ey, Kristin, Moscow Prime Time: How the Soviet Union Built the Media Empire That Lost the Cultural Cold War (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011). The important story of Soviet TV in its heyday is told in Evans, Christine, Between Truth and Time: A History of Soviet Central Television (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016). On the earlier medium of broadcasting, see Lovell, Stephen, Russia in the Microphone Age: A History of Soviet Radio, 1919–1970 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). Another branch of the post-Stalin culture industry forms the subject of Wolfe, Thomas C., Governing Soviet Journalism: The Press and the Socialist Person After Stalin (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005).

Useful studies of other media systems in communist Eastern Europe include Goban-Klas, Tomasz, The Orchestration of the Media: The Politics of Mass Communications in Communist Poland and the Aftermath (Boulder: Westview Press, 1994), Curry, Jane Leftwich, Poland’s Journalists: Professionalism and Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), Robinson, Gertrude Joch, Tito’s Maverick Media: The Politics of Mass Communications in Yugoslavia (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977), Gumbert, Heather L., Envisioning Socialism: Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2014), Fiedler, Anke, Medienlenkung in der DDR (Cologne: Böhlau, 2014), and Bren, Paulina, The Greengrocer and His TV: The Culture of Communism After the 1968 Prague Spring (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010).

The international perspective on communist media and culture is explored in a number of chapters in Gorsuch, Anne E. and Koenker, Diane P. (eds.), The Socialist Sixties: Crossing Borders in the Second World (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013). On the challenge from abroad to communist broadcasting, see Nelson, Michael, War of the Black Heavens: The Battles of Western Broadcasting in the Cold War (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1997). For a more detailed collection, see Johnson, A. Ross and Parta, R. Eugene (eds.), Cold War Broadcasting: Impact on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2010).

On China, Volland, Nicolai offers an excellent historical study of the CCP’s “media concept’” in his Ph.D. dissertation, “The Control of the Media in the People’s Republic of China” (University of Heidelberg, 2003). Schoenhals, Michael, Doing Things with Words in Chinese Politics: Five Studies (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), is an illuminating study of the discursive rules of the game in communist China. The best place to start on more recent developments is Brady, Anne-Marie, Marketing Dictatorship: Propaganda and Thought Work in Contemporary China (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008).

Bibliographical Essay

On the institutionalization of Socialist Realism, see Clark, Katerina, The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), and Dobrenko, Evgenii, Political Economy of Socialist Realism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007). Archive-based studies of the Soviet “Thaw” include: Jones, Polly, Myth, Memory, Trauma: Rethinking the Stalinist Past in the Soviet Union, 1953–1970 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013); Kozlov, Denis, The Readers of Novyi Mir: Coming to Terms with the Stalinist Past (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013); Kozlov, Denis and Gilburd, Eleonory (eds.), The Thaw: Soviet Society and Culture During the 1950s and 1960s (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013). On comparisons of Eastern bloc “Thaws,” see Segel, Harold B., The Columbia Guide to the Literatures of Eastern Europe Since 1945 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003); Cornis-Pope, Marcel and Neubauer, John (eds.), History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2004).

On the post-Stalinist intelligentsia, see Zubok, Vladislav, Zhivago’s Children: The Last Russian Intelligentsia (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009); Kagarlitsky, Boris, The Thinking Reed: Intellectuals and the Soviet State 1917 to the Present (London: Verso, 1989). Late Soviet cultural politics is currently analyzed mostly in memoirs and Russian-language scholarship, of which the most systematic is Kretzschmar, Dirk, Politika i kulʹtura pri Brezhneve, Andropove i Chernenko, 1970–1985 [Politics and Culture Under Brezhnev, Andropov and Chernenko, 1970–1985] (Moscow: AIRO-XX, 1997). Older studies of Soviet literary institutions (Garrard, John Gordon and Garrard, Carol, Inside the Soviet Writers’ Union [London: I. B. Tauris, 1990]; Dewhirst, Martin and Farrell, Robert [eds.], The Soviet Censorship [Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1973]) still contain valuable insights for the period. Useful overviews of Czechoslovak literary politics include Holý, Jiří, Writers Under Siege: Czech Literature Since 1945 (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2008), and Šimečka, Milan, The Restoration of Order: The Normalization of Czechoslovakia 1969–1976 (London: Verso, 1984), while the normalization-era intelligentsia is analyzed in Bolton, Jonathan, Worlds of Dissent: Charter 77, the Plastic People of the Universe, and Czech Culture Under Communism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), and Bren, Paulina, The Greengrocer and His TV: The Culture of Communism After the 1968 Prague Spring (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010). Writers’ polemics against official culture include Solzhenitsyn, Alexander, The Oak and the Calf (London: Collins and Harvill, 1980), and Haraszti, Miklós, The Velvet Prison (New York: Basic Books, 1988).

Much valuable analysis of “official” literature appeared during and just after the period. On Soviet literature, see Brown, Deming’s Soviet Russian Literature Since Stalin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978) and The Last Years of Soviet Russian Literature: Prose Fiction, 1975–1991 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), as well as Shneidman, Nicholas, Soviet Literature in the 1970s: Artistic Diversity and Ideological Conformity (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1979), and Hosking, Geoffrey, Beyond Socialist Realism: Soviet Fiction Since Ivan Denisovich (London: Granada, 1980). The only book-length study of “Aesopian” language remains Losev, Lev, On the Beneficence of Censorship: Aesopian Language in Modern Russian Literature (Munich: O. Sagner in Kommission, 1984). In addition to Segel, Holý and Cornis-Pope, wide-ranging accounts of Czechoslovak literature include Chitnis, Rajendra, Literature in Post-Communist Russia and Eastern Europe: The Russian, Czech and Slovak Fiction of the Changes, 1988–1998 (London: Routledge Curzon, 2005), and Pynsent, Robert, “Social Criticism in Czech Literature of 1970s and 1980s Czechoslovakia,” Bohemia 27, 1 (1986), 1–36.

Samizdat is an area of burgeoning interest, thanks to access to documents and interest in alternative public spheres: Behrends, Jan C. and Lindenberger, Thomas (eds.), Underground Publishing and the Public Sphere: Transnational Perspectives (Vienna: Lit, 2014), Komaromi, Ann, Uncensored: Samizdat Novels and the Quest for Autonomy in Soviet Dissidence (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2015), and two special issues of Poetics Today, edited by Vladislav Todorov, “Publish & Perish: Samizdat and Underground Cultural Practices in the Soviet Bloc,” 29, 4 (2008) and 30, 1 (2009). Tamizdat has received less attention, with the exception of the ground-breaking volumes Kind-Kovács, Friederike, Written Here, Published There: How Underground Literature Crossed the Iron Curtain (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2014); and Kind-Kovács, Friederike and Labov, Jessie (eds.), Samizdat, Tamizdat, and Beyond: Transnational Media During and After Socialism (New York: Berghahn Books, 2013).

Bibliographical Essay

An excellent introduction is provided in Harsch, Donna, “Communism and Women,” in Smith, Stephen A. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Communism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 488–504; Penn, Shana and Massino, Jill (eds.), Gender Politics and Everyday Life in State Socialist Eastern and Central Europe (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Fodor, Éva, Working Difference: Women’s Working Lives in Austria and Hungary, 1945–1995 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003); Havelková, Hana and Oates-Indruchová, Libora (eds.), The Politics of Gender Culture Under State Socialism: An Expropriated Voice (London: Routledge, 2014); Christian, Michel and Heiniger, Alix (eds.), “Dossier: femmes, genre, et communisme,” Vingtième Siècle. Revue d’Histoire 2 (2015) (special issue); Kott, Sandrine and Thébaud, Françoise (eds.), “Le ‘socialisme reel’ à l’épreuve du genre,” Clio: Femmes, Genre, Histoire 41 (2015) (special issue). On the postwar period, see Fidelis, Malgorzata, Women, Communism and Industrialization in Postwar Poland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), and Harsch, Donna, The Revenge of the Domestic: Women, the Family and Communism in the German Democratic Republic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), while the sexual revolution in East Germany is explored in McLellan, Josie, Love in the Time of Communism: Intimacy and Sexuality in the GDR (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011). On the gendered nature of dissent and resistance, see Kenney, Padraic, “The Gender of Resistance in Communist Poland,” American Historical Review 104 (1999), 399–425.

State feminism in Eastern Europe and China is debated in de Haan, Francisca (ed.), ‘Ten Years After: Communism and Feminism Revisited,” Aspasia 10 (2016), 102–68; Bonfiglioli, Chiara, “Cold War Internationalisms, Nationalisms and the Yugoslav–Soviet Split: The Union of Italian Women and the Antifascist Women’s Front of Yugoslavia,” in de Haan, Francisca et al. (eds.), Women’s Activism: Global Perspectives from the 1890s to the Present (London: Routledge, 2013), 59–76; Nowak, Basia, “Constant Conversations: Agitators in the League of Women in Poland During the Stalinist Period,” Feminist Studies 31 (2005), 488–518; Zheng, Wang, Finding Women in the State: A Socialist Feminist Revolution in the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1964 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016); de Haan, Francisca, “Continuing Cold War Paradigms in the Western Historiography of Transnational Women’s Organisations: The Case of the Women’s International Democratic Federation (WIDF),” Women’s History Review 19, 4 (Sep. 2010), 547–73; Donert, Celia, “Women’s Rights in Cold War Europe: Disentangling Feminist Histories,” Past & Present 218, supplement 8 (2013), 180–202.

Contemporary studies by émigré scholars, or observers of communist regimes during the Cold War, include Heitlinger, Alena, Women and State Socialism: Sex Inequality in the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1979); Scott, Hilda, Does Socialism Liberate Women? Experiences from Eastern Europe (Boston: Beacon Press, 1974); Molyneux, Maxine, Women’s Emancipation Under Socialism: A Model for the Third World? (Brighton: IDS Publications, 1981); Kruks, Sonia, Rapp, Rayna and Young, Marilyn B., Promissory Notes: Women and the Transition to Socialism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1989).

East–West transnational connections between female activists after 1968 are explored in Wu, Judy, Radicals on the Road: Internationalism, Orientalism, and Feminism During the Vietnam Era (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013); Lóránd, Zsófia, “‘A Politically Non-Dangerous Revolution Is Not a Revolution’: Critical Readings of the Concept of Sexual Revolution by Yugoslav Feminists in the 1970s,” European Review of History – Revue européenne d’histoire 22, 1 (2015), 120–37.

On the gendered dimensions of socialist internationalism, see Hong, Young-Sun, Cold War Germany, the Third World, and the Global Humanitarian Regime (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015); see also Slobodian, Quinn (ed.), Comrades of Color: East Germany in the Cold War World (New York: Berghahn, 2015); Alamgir, Alena, “Recalcitrant Women: Internationalism and the Redefinition of Welfare Limits in the Czechoslovak–Vietnamese Labor Exchange Program,” Slavic Review 73, 1 (2014), 133–55; Donert, Celia, “From Communist Internationalism to Human Rights: The Women’s International Democratic Federation Mission to North Korea, 1951,” Contemporary European History 25, 2 (2016), 313–33.

Cold War conflicts over women’s rights at the UN are explored in Baldez, Lisa, Defying Convention: US Resistance to the UN Treaty on Women’s Rights (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), especially chs. 2 and 3. More broadly, see Boris, Eileen and Zimmermann, Susan (eds.), Women’s ILO: Transnational Networks, Global Labour Standards and Gender Equity, 1919 to the present (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming), and Jain, Devaki, Women, Development, and the UN: A Sixty-Year Quest for Equality and Justice (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005). For a state-socialist perspective, see Ghodsee, Kristen, “Rethinking State Socialist Mass Women’s Organisations: The Committee of the Bulgarian Women’s Movement and the United Nations Decade for Women, 1975–1985,” Journal of Women’s History 24, 4 (2012), 49–73; Donert, Celia, “Whose Utopia? Gender, Ideology and Human Rights at the 1975 World Congress of Women in East Berlin,” in Eckel, Jan and Moyn, Samuel (eds.), The Breakthrough: Human Rights in the 1970s (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), 68–87; Raluca Popa, “Translating Equality Between Women and Men Across Cold War Divides: Women Activists from Hungary and Romania and the Creation of International Women’s Year,” in Penn and Massino (eds.), Gender Politics and Everyday Life, 59–73.

On feminism and postsocialism, see Sperling, Valerie, Organizing Women in Contemporary Russia: Engendering Transition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999); Fábián, Katalin (ed.), Domestic Violence in Postcommunist States: Local Activism, National Policies, and Global Forces (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010); Hemment, Julie, Empowering Women in Russia: Activism, Aid, and NGOs (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007); Helms, Elissa, Innocence and Victimhood: Gender, Nation, and Women’s Activism in Postwar Bosnia-Herzegovina (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2013); Suchland, Jennifer, Economies of Violence: Transnational Feminism, Postsocialism and the Politics of Sex Trafficking (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015); Zheng, Wang and Zhang, Ying, “Global Concepts, Local Practices: Chinese Feminism Since the Fourth UN Conference on Women,” Feminist Studies 36 (2010), 40–70; Guenther, Katja, Making Their Place: Feminism After Socialism in Eastern Germany (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010); Ferree, Myra Marx, Varieties of Feminism: German Gender Politics in Global Perspective (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012).

Suggested Readings

Bibliographical Essay

The fields of women’s studies and critical studies on men and masculinities have had an uneven trajectory. While scholarship on the position of women in the USSR and the PRC traces its roots to the late 1960s and early 1970s, critical studies on Chinese and Russo-Soviet masculinities did not emerge until the late 1990s. While women’s studies constitute a fundamental part of both communist and postcommunist studies, the scholarship on the masculinity side of the gender equation remains in a relatively nascent phase.

For the evolution of Russian and Soviet women’s history, see Alpern, Barbara Engel, “New Directions in Russian and Soviet Women’s History,” in Nadell, Pamela S. and Haulman, Kate (eds.), Making Women’s Histories: Beyond National Perspectives (New York: New York University Press, 2013), 38–60. For the development of scholarly studies on Chinese women in both China and the West, see Hershatter, Gail and Zheng, Wang, “Chinese History: A Useful Category of Gender Analysis,” American Historical Review 113, 5 (2008), 1404–21. The position of women under communism is analyzed in Harsch, Donna, “Communism and Women,” in Smith, Stephen A. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Communism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 488–504.

A useful overview of scholarship on Russian and Soviet masculinities emerges in Clements, Barbara Evans, Friedman, Rebecca and Healey, Dan (eds.), Russian Masculinities in History and Culture (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002). A theoretical and longue durée approach to Chinese masculinity receives coverage in Louie, Kam, Theorising Chinese Masculinity: Society and Gender in China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Two works that delineate the Soviet and Chinese Communist Parties’ paradoxical attitude toward women, as simultaneously sociopolitically regressive elements and embodiments of historical progress and social change, see Wood, Elizabeth A., The Baba and the Comrade: Gender and Politics in Revolutionary Russia (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997); and Chen, Tina Mai, “Female Icons, Feminist Iconography? Socialist Rhetoric and Women’s Agency in 1950s China,” Gender and History 15, 2 (2003), 268–95.

Evaluations of Soviet women’s contribution to Stalin’s industrial revolution and of their World War II combat roles are presented, respectively, in Goldman, Wendy, Women at the Gates: Gender and Industry in Stalin’s Russia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), and Krylova, Anna, Soviet Women in Combat: A History of Violence on the Eastern Front (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011). The transformation of women’s sociopolitical roles under Mao receives scrutiny in Honig, Emily, “Socialist Sex: The Cultural Revolution Revisited,” Modern China 29, 2 (2003), 143–75, and Honig, Emily, “Iron Girls Revisited: Gender and the Politics of Work in the Cultural Revolution,” in Entwisle, Barbara and Henderson, Gail E. (eds.), Re-Drawing Boundaries: Work, Households, and Gender in China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 97–110.

For the fundamental transformation the masculinity ideal underwent during the first three decades of Soviet rule, see both Borenstein, Eliot, Men Without Women: Masculinity and Revolution in Russian Fiction, 1917–1929 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001), and Kaganovsky, Lilya, How the Soviet Man Was Unmade: Cultural Fantasy and Male Subjectivity Under Stalin (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2008). For the Chinese revolutionary project’s impact on the social construct of masculinity, see Hinsch, Bret, Masculinities in Chinese History (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013), 151–70.

The various elements of the late socialist Soviet masculinity crisis are featured in Zdravomyslova, Elena and Temkina, Anna, “The Crisis of Masculinity in Late Soviet Discourse,” Russian Social Science Review 54, 1 (2013), 40–61. Two studies that identify the rapidly changing gender politics after Mao’s death include Baranovitch, Nimrod, China’s New Voices: Popular Music, Ethnicity, Gender, and Politics, 1978–1997 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), as well as Zheng, Wang, “From Xianglin’s Wife to the Iron Girls: The Politics of Gender Representation,” in Goodman, David S. G. (ed.), Handbook of the Politics of China (Northampton, MA: Edward Edgar, 2015).

For an overview of how men’s domestic roles changed after the fall of the Soviet Union, see Ashwin, Sarah and Lytkina, Tatyana, “Men in Crisis in Russia: The Role of Domestic Marginalization,” Gender and Society 18, 2 (2004), 189–206. The emergence of the neoliberal entrepreneurial ethos and its impact on gender relations are covered in Mazzarino, Andrea, “Entrepreneurial Women and the Business of Self-Development in Global Russia,” Signs 38, 3 (2013), 623–45, and Yurchak, Alexei, “Russian Neoliberal: The Entrepreneurial Ethic and the Spirit of ‘True Careerism,’” Russian Review 62, 1 (2003), 72–90. The hypermasculine and ethnoexclusivist politics of the Putin era is examined in Riabov, Oleg and Riabova, Tatiana, “The Remasculinization of Russia? Gender, Nationalism, and the Legitimation of Power Under Vladimir Putin,” Problems of Post-Communism 61, 2, (2014), 23–35.

The realities of female entrepreneurs in China receive treatment in Chen, Minglu, Tiger Girls: Women and Enterprise in the People’s Republic of China (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011). Monographs on women factory workers include Ngai, Pun, Made in China: Women Factory Workers in a Global Workplace (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), and Jacka, Tamara, Rural Women in Urban China: Gender, Migration, and Social Change (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2006). For a comprehensive treatment of contemporary Chinese masculinities, see Song, Geng and Hird, Derek, Men and Masculinities in Contemporary China (Leiden: Brill, 2014).