Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Author's Preface

- Acronyms

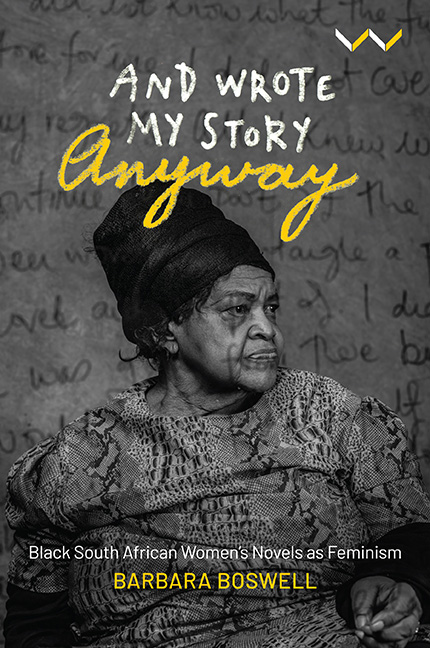

- Introduction: ‘And Wrote My Story Anyway’: Black South African Women's Novels as Feminism

- 1 Writing as Activism: A History of Black South African Women's Writing

- 2 Rewriting the Apartheid Nation: Miriam Tlali and Lauretta Ngcobo

- 3 Dissenting Daughters: Girlhood and Nation in the Fiction of Farida Karodia and Agnes Sam

- 4 Interrogating ‘Truth’ in the Post-Apartheid Nation: Zoë Wicomb and Sindiwe Magona

- 5 Making Personhood: Remaking History in Yvette Christiansë and Rayda Jacobs's Neo-Slave Narratives

- 6 Black Women Writing ‘New’ South African Masculinities: Kagiso Lesego Molope and Zukiswa Wanner

- Conclusion: Towards a Black South African Feminist Criticism

- Select Bibliography

- Index

4 - Interrogating ‘Truth’ in the Post-Apartheid Nation: Zoë Wicomb and Sindiwe Magona

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 June 2021

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Author's Preface

- Acronyms

- Introduction: ‘And Wrote My Story Anyway’: Black South African Women's Novels as Feminism

- 1 Writing as Activism: A History of Black South African Women's Writing

- 2 Rewriting the Apartheid Nation: Miriam Tlali and Lauretta Ngcobo

- 3 Dissenting Daughters: Girlhood and Nation in the Fiction of Farida Karodia and Agnes Sam

- 4 Interrogating ‘Truth’ in the Post-Apartheid Nation: Zoë Wicomb and Sindiwe Magona

- 5 Making Personhood: Remaking History in Yvette Christiansë and Rayda Jacobs's Neo-Slave Narratives

- 6 Black Women Writing ‘New’ South African Masculinities: Kagiso Lesego Molope and Zukiswa Wanner

- Conclusion: Towards a Black South African Feminist Criticism

- Select Bibliography

- Index

Summary

The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) has, arguably, been this country's most ambitious post-apartheid nation-building project. As a nationalist apparatus in an emerging democracy, the Commission was conceived of to unify a fractured people and construct the ‘Rainbow Nation’ conceived of by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the anti-apartheid cleric who eventually came to serve as TRC chairperson. In an attempt to uncover the ‘truth’ of the gross human rights abuses committed during apartheid, it started to hear testimony in 1997, soon after the birth of democracy in 1994. It also strove to foster national reconciliation and forge unity after decades of division and violence. But how did the practices of, and the discourses generated by, the TRC as a nation-building project situate women in this new nation?

Feminist theorists have long noted the contested relationship between nationalisms and women. In seeking to forge the united ‘imagined political communities’ (Anderson 1991, 6) that constitute national formations, nationalisms gender women as always different to male subjects in relation to the state (Yuval-Davis and Anthias 1989; Boehmer 1991; McClintock 1995; Kaplan, Alarcon and Moallem 1999; Layoun 2001). In nation-building processes, the concept ‘woman’ is often deployed as a sign of the nation (Ray 2000), allowing male subjects to position themselves in relation to their country in the same way as they stand in relation to women (McClintock 1995). Thus, male critics figure the nation as feminine, often in need of protection, or in the case of war, open to invasion in the same way women's bodies are protected or invaded. Feminist critics (Boehmer 1991; Jayawardena 1986; McClintock 1995) have likewise theorised nationalism as inherently patriarchal and dangerous, especially in the ways it positions women as different to men by institutionalising gender difference. Thus, while key nation-building moments such as those produced by the staging of the TRC may hold liberatory potential for women, they may also be perilous in the ways that they discursively produce women citizens.

Zoë Wicomb's David's Story (2000) and Sindiwe Magona's Mother to Mother (1998) exemplify a black literary feminism which interrupts and interrogates a number of nation-building discourses that position women in precarious ways in relation to the new South African nation.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- And Wrote My Story AnywayBlack South African Women's Novels as Feminism, pp. 115 - 144Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2021