Summary

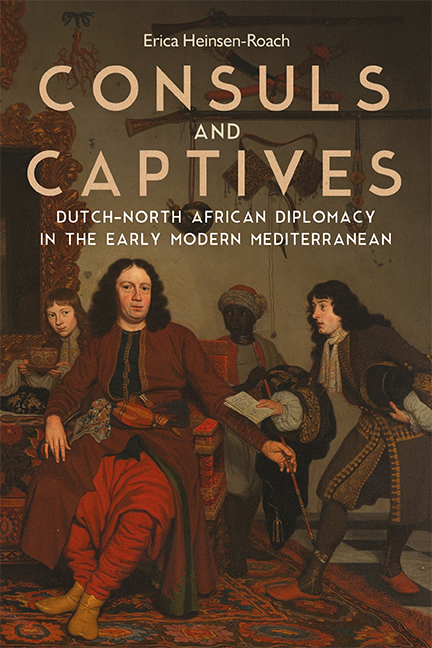

In 1687, the Dutch artist Michiel van Musscher painted a portrait of fiftytwo- year-old Thomas Hees in his capacity as extraordinary ambassador to North Africa. The painting belongs to a genre known as the commemorative portrait, a seventeenth-century form in which high-ranking European officials, travelers, and merchants commissioned artists to immortalize their travels abroad. Between 1675 and 1685, Hees completed several missions to the Maghrib, where he concluded treaties with Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli and ransomed almost two hundred Dutch crew members held in captivity. While Hees was negotiating the liberation of the Dutch captives in the Maghrib, Abraham de Wicquefort, a fellow Dutch diplomat residing at different European courts, wrote L’Ambassadeur et ses Fonctions, first published in 1681. “The right of embassy,” de Wicquefort posited, “is the most illustrious mark of sovereignty.” Only an ambassador, he reasoned, had the status and authority to represent a sovereign power and negotiate the political affairs of the state. Hees seemed to embody de Wicquefort's view of the ambassador’s significance in sustaining international relations. Even though he was unable to free all the captives, on his return to the Dutch Republic he commissioned Musscher to visualize his experience as ambassador to the Maghrib.

At first sight, de Wicquefort's remarks—and, seemingly, the painting— exemplify traditional historical interpretations that envisioned resident ambassadors at the center of Europe's political machinery, a concept that would eventually become the model for establishing a worldwide diplomatic international order. Hees, seated with stretched legs at a table in the center and holding a pipe, fashions himself as the patriarch of the family. His nephews, twenty-four-year-old Andries Hees and sixteen-year-old Jan Hees, hand him his appointment letter and tobacco jar, respectively. Behind the chair stands seventeen-year-old Thomas, a black servant. On the table at the ambassador's right, an atlas open to a map of Barbary illustrates where his mission has taken him. A globe, an ink set, and on the wall behind him, the coat of arms of the States General depicting a lion with sword, complete the image of the ambassador as a man of the world and a patriarch representing the interests of the Dutch Republic.

Yet Hees's portrait and others that belong to the commemorative portrait genre also challenge the traditional categories used to define diplomacy.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Consuls and CaptivesDutch-North African Diplomacy in the Early Modern Mediterranean, pp. 1 - 14Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019