Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Note on Transliteration

- Note on Sources and Conventions

- Introduction: A Portrait of the Artist

- 1 In God’s Image

- 2 The ‘Great Thing’ and the ‘Small Thing’: Mishneh Torah as Microcosm

- 3 Emanation

- 4 Return

- 5 From Theory to History, via Midrash: A Commentary on ‘Laws of the Foundations of the Torah’, 6: 9 and 7: 3

- 6 Conclusion: Mishneh Torah as Parable

- Appendix I The Books and Sections of Mishneh Torah

- Appendix II The Philosophical Background

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index of Citations

- Index of Subjects

Appendix II - The Philosophical Background

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Note on Transliteration

- Note on Sources and Conventions

- Introduction: A Portrait of the Artist

- 1 In God’s Image

- 2 The ‘Great Thing’ and the ‘Small Thing’: Mishneh Torah as Microcosm

- 3 Emanation

- 4 Return

- 5 From Theory to History, via Midrash: A Commentary on ‘Laws of the Foundations of the Torah’, 6: 9 and 7: 3

- 6 Conclusion: Mishneh Torah as Parable

- Appendix I The Books and Sections of Mishneh Torah

- Appendix II The Philosophical Background

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index of Citations

- Index of Subjects

Summary

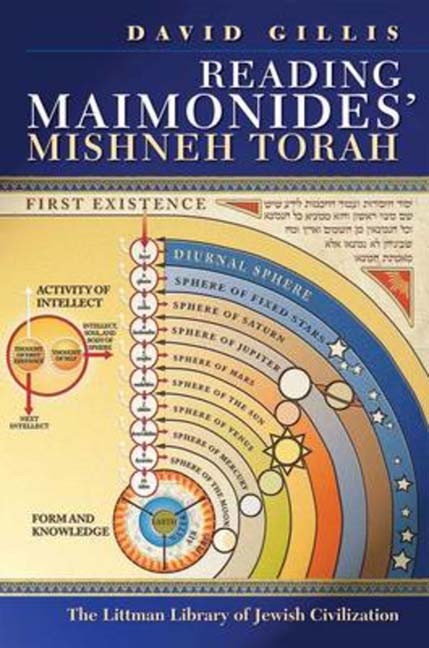

Outline of Neoplatonism

The school of thought known as Neoplatonism arose in Rome in the third century ce. It is so called because it represents a return, with modifications, to the doctrines of Plato after his pupil Aristotle's rejection of them. Plotinus, who studied philosophy in Alexandria and arrived in Rome in about 244, is generally considered to be the first and foremost figure of the school. His pupil Porphyry collected and edited his writings, and between 300 and 305 published them as the Enneads. Aristotle, it is worth recalling, died in 322 bce, so that the interval between him and Plotinus is five and a half centuries.

In the Islamic world Plotinus was hardly known by name. Parts of the Enneads circulated in Arabic paraphrases, such as The Theology of Aristotle.The medieval Islamic philosophers attributed this and other versions of Plotinus’ works to Aristotle, and tend to amalgamate the thought of both of them in their metaphysics. Whether or not Maimonides read The Theology of Aristotle or any similar work is not known for sure. Herbert Davidson detects no reference or allusion to such works in the Guide. Alfred Ivry, on the other hand, states forthrightly, on the basis of a comparison of some of the teachings of the Guide with those of the Enneads, that ‘The striking parallels that emerge offer persuasive evidence that this text, originally in Greek, had considerable influence in its Arabic versions upon Maimonides’ thinking, directly as well as indirectly, and that it is a major source of Maimonides’ philosophy.’ At any rate, familiarity with Neoplatonic ideas was guaranteed by Maimonides’ reading of Alfarabi and Avicenna, whose writings contain a noted Neoplatonic strain, and also through his knowledge of Ismaili writings.

Aristotle differed from Plato on the status of universals, that is, properties such as ‘chair-ness’, ‘humanity’, ‘right-angled triangle’. Plato was a realist, holding that universals really exist as ideal Forms, and that the chairs, human beings, and right-angled triangles we see are but imperfect copies of the Forms. Aristotle held form to be immanent in matter, inseparable from it but distinguishable in the mind. Both these philosophers considered knowledge to be the perception of form, but whereas for Plato this ultimately meant seeing beyond material existence to the realm of the Forms, for Aristotle it meant extracting form from matter;

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Reading Maimonides' Mishneh Torah , pp. 391 - 402Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2015