Foreword

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 May 2024

Summary

The sober and impartial investigation into the destruction of music carried out by the anti-Semitism of Nazi Germany began in the mid-1980s. It was a time when the last survivors, and those weighed down by complicity, or by the collaboration of parents or teachers, could be recalled as witnesses of time, place and situation, and yet none of the occupied countries – apart from Czechoslovakia (as it then was), with the discovery of the musical riches originating in the Theresienstadt (Terezín) Ghetto – moved forward in an attempt to recover local legacies that had been lost. I have in the past referred to this disinclination as the ‘Anne Frank Syndrome’: a belief that to acknowledge the losses during the Nazi occupation vicariously implicated locals, who for decades had prided themselves on their acts of resistance. Collaboration, or indeed complicity, were meant to remain buried beneath the floorboards, under a carpet of local mythology. To ask what happened to this composer, musician or singer would inevitably lead to uncomfortable questions, as indeed it had done in the story of Anne Frank. It is the main reason that few of the occupied countries have bothered to lift that carpet of mythology and look beneath the floorboards. What they would find would be too compromising, too embarrassing, and the tale of noble resistance to Nazi brutality would be exposed for all as a fairy tale.

Czechoslovakia began its own recovery of its lost musical legacy in the early 1990s, following similar initiatives by Germany begun in the mid-1980s. Even before Austria, it was the first of the Nazi-occupied countries to confront the loss of composers and musicians held in Theresienstadt, subsequently deported to Auschwitz and murdered. The Orpheus Trust and Exilarte Center in Austria joined the Leo Smit Foundation in the Netherlands in the mid-1990s. As this publication demonstrates, the findings of the Leo Smit Foundation have been astonishing, given the sheer number of important composers and other musicians lost during the years of German occupation. These findings have also been revelatory in their significance: those lost musicians were important voices who would have made a difference to the reputation of the Netherlands as a musical nation had they been allowed to live.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

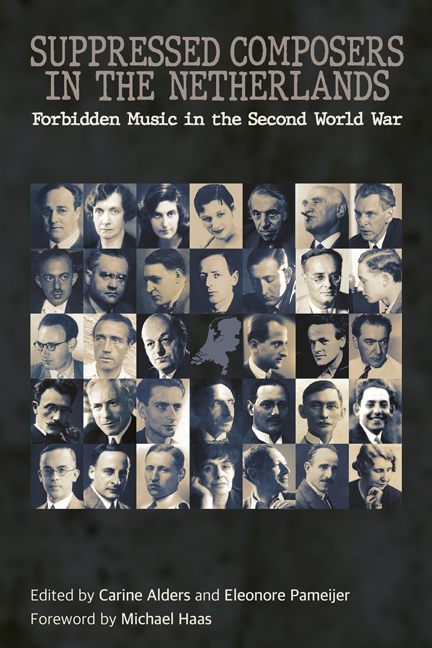

- Suppressed Composers in the NetherlandsForbidden Music in the Second World War, pp. 9 - 12Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2024