Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I THE ROMAN PRINCEPS

- PART II THE ROMAN THEORY AND THE FORMATION OF THE RENAISSANCE PRINCEPS

- PART III THE HUMANIST PRINCEPS IN THE TRECENTO

- PART IV THE HUMANIST PRINCEPS FROM THE QUATTROCENTO TO THE HIGH RENAISSANCE

- PART V THE MACHIAVELLIAN ATTACK

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- IDEAS IN CONTEXT

- References

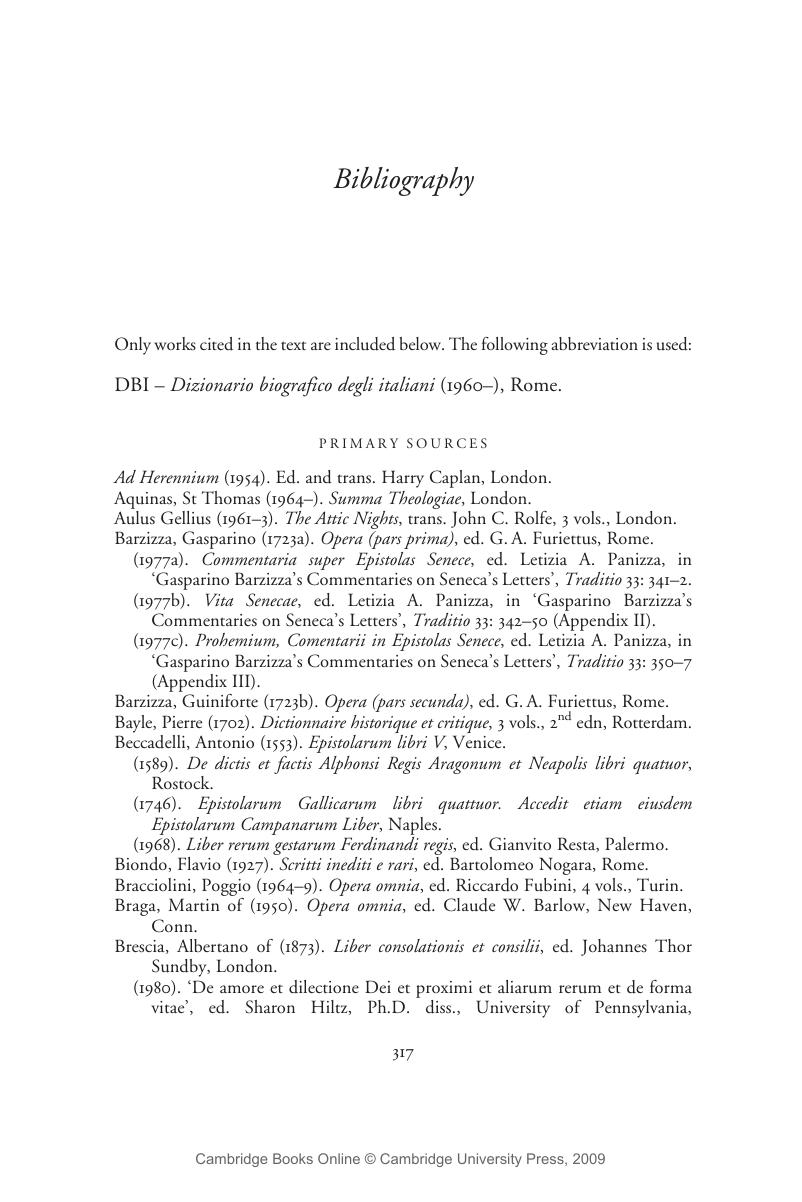

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 September 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I THE ROMAN PRINCEPS

- PART II THE ROMAN THEORY AND THE FORMATION OF THE RENAISSANCE PRINCEPS

- PART III THE HUMANIST PRINCEPS IN THE TRECENTO

- PART IV THE HUMANIST PRINCEPS FROM THE QUATTROCENTO TO THE HIGH RENAISSANCE

- PART V THE MACHIAVELLIAN ATTACK

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- IDEAS IN CONTEXT

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Roman Monarchy and the Renaissance Prince , pp. 317 - 331Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2007