Introduction

The Woman Veteran as a World War II Memoirist

Summary

“Mother, I cannot explain it to you,” Tania said, “but…if, they assign me to a hospital behind the lines I will ask them to send me to the front.…I am not afraid of the front.…When I was in the resistance, I lived with an elderly woman who also was a doctor: she and I would go to sleep at night but could not sleep, so we would lie and not sleep and I would tell her: ‘Sofia Leonidovna, what would I not give right now in order to be at the front?! What happiness it is to work at some frontline medical station among your own!’ We talked about the front like about happiness, do you understand? Because we lived among the Germans who could take us away every minute.”

Tania Ovchinnikova's monologue from The Living and the Dead – Part Two, by Konstantin Simonov, Soviet wartime journalist, poet, writer“If she is here, let her come in,” I heard the [lieutenant's] voice. “Listen,” the company commander began, “we have decided that you will stay temporarily here, at the headquarters, together with medical instructor Mariia.” The blood rushed to my face: “Comrade Lieutenant, allow me!…I cannot be a medical orderly. I do not know how to attend to the wounds. I was trained to fire from the machine gun.…I am a woman machine gunner, comrade Lieutenant!”

The Youth Burned by Fire (Military Memoirs), by Zoia Medvedeva, Soviet machine gunner, senior lieutenant, female commander of a male machine-gun company during World War II- Type

- Chapter

- Information

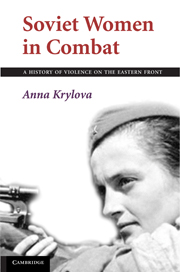

- Soviet Women in CombatA History of Violence on the Eastern Front, pp. 1 - 32Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2010