Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 May 2017

Summary

Historical Overview

A gifted raconteur, Hans J. Massaquoi has lived an adventurous life. Born in 1926 as the son of a Liberian father and a German mother, he grew up in Hamburg, where he survived the war despite several close calls. Afterwards he emigrated briefly to Liberia and then to the U.S., where he made a career for himself as editor of the black magazine Ebony. His 1999 memoir, Destined to Witness, is being marketed by Harper Collins in the U.S. under the rubric of “Holocaust Studies.” The publicity flyer announces the story of “a young black child growing up in Nazi Germany” and hails Massaquoi's “account of surviving the Holocaust.” Massaquoi's book was also a bestseller in its German translation, which appeared as “Neger, Neger, Schornsteinfeger!” The German title literally translates as “Nigger, Nigger, Chimneysweep!” and sounds like a childhood taunt that Massaquoi likely endured. While the English title emphasizes Massaquoi's survival of the Nazi period, the German title points up his isolation as a black child in supposedly “Aryan” Germany. The larger question here is where Massaquoi's story belongs. Is it a Holocaust narrative, or does it belong to the growing body of literature produced by Afro-Germans? While both readings are possible, Massaquoi's story shows how Afro-German experience itself is ambiguous and open to multiple interpretations.

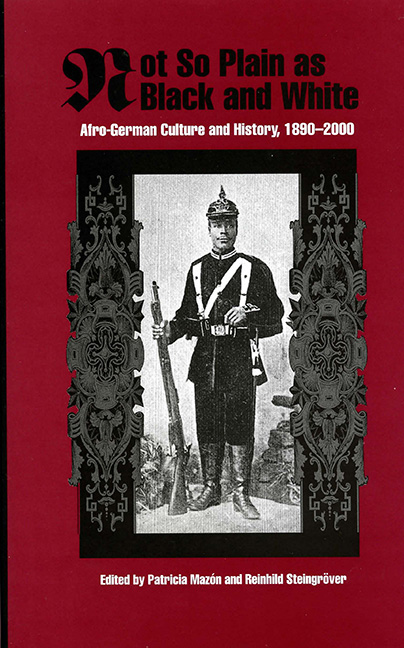

Contact between Germans and Africans goes back not decades but centuries. Africans were first brought to Europe beginning in the 1400s as living curiosities. In Germany they were mostly slaves, court servants, and military band drummers. Best known among these early African Germans was the eighteenth-century philosopher Wilhelm Anton Amo, who taught at the University of Halle and was brought from Ghana as a small boy. Usually blacks lived scattered across Germany, but in the eighteenth century there was at least one German village with exclusively black inhabitants, the “Mohrenkolonie Mulang” near Kassel. After Germany became a unified nation in 1871, it acquired the colonies of German Southwest Africa, German East Africa, Togo, and Cameroon in 1884–85 but lost them at the end of World War I.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Not So Plain as Black and WhiteAfro-German Culture and History, 1890–2000, pp. 1 - 24Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2005