Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Contents

- Ancient Mathematics

- Foreword

- Sherlock Holmes in Babylon

- Words and Pictures: New Light on Plimpton 322

- Mathematics, 600 B.C.–600 A.D.

- Diophantus of Alexandria

- Hypatia of Alexandria

- Hypatia and Her Mathematics

- The Evolution of Mathematics in Ancient China

- Liu Hui and the First Golden Age of Chinese Mathematics

- Number Systems of the North American Indians

- The Number System of the Mayas

- Before The Conquest

- Afterword

- Medieval and Renaissance Mathematics

- The Seventeenth Century

- The Eighteenth Century

- Index

- About the Editors

Mathematics, 600 B.C.–600 A.D.

from Ancient Mathematics

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Contents

- Ancient Mathematics

- Foreword

- Sherlock Holmes in Babylon

- Words and Pictures: New Light on Plimpton 322

- Mathematics, 600 B.C.–600 A.D.

- Diophantus of Alexandria

- Hypatia of Alexandria

- Hypatia and Her Mathematics

- The Evolution of Mathematics in Ancient China

- Liu Hui and the First Golden Age of Chinese Mathematics

- Number Systems of the North American Indians

- The Number System of the Mayas

- Before The Conquest

- Afterword

- Medieval and Renaissance Mathematics

- The Seventeenth Century

- The Eighteenth Century

- Index

- About the Editors

Summary

600 B.C.–400 B.C.

Introduction

Isolated arithmetical and geometrical facts were, without doubt, known in prehistoric times much as such facts are now known among the most primitive tribes. Rather advanced mathematical knowledge appears in ancient Egyptianpapyri (for instance in the Rhind Papyrus of the 14th century B.C.) and on numerous Babylonian cuneiform texts dating from 2000 B.C. onwards. Certainly the Greeks learned many of the algebraic methods and the techniques of geometric measurements from these ancient peoples through the lively commerce of the Eastern Mediterranean. Our reports begin with Greek mathematics after 600 B.C.

Sources

The sources for the history of mathematics in Greece during the period from 600 B.C. to 400 B.C. are very scarceand unreliable. We have a fragment of mathematical history by Eudemus (ca. 320 B.C.) in an excerpt of thesixth century A.D. This fragment itself is in a bad state, corrupted by later changes. There are, however, scattered among the works of Greek authors, enough passages concerned with the mathematics and mathematicians of Ancient Greece, for us to derive a fairly clear idea of this early period.

Early Greeks

While there is no mathematician known from ancient Egypt or Babylon, we do know the names of famous Greek mathematicians.

Thales (ca. 600 B.C.) of Miletus (see map), who was probably of Phoenician origin, is known as the fatherof Greek mathematics. He had many disciples. It may be that there is a direct connection between him and Pythagoras (ca. 550 B.C.) from Samos.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

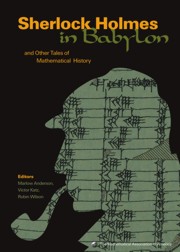

- Sherlock Holmes in BabylonAnd Other Tales of Mathematical History, pp. 27 - 40Publisher: Mathematical Association of AmericaPrint publication year: 2003