Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- Dedication

- Introduction: Sounding Liverpool

- 1 George Garrett, Merseyside Labour and the Influence of the United States

- 2 ‘No Struggle but the Home’: James Hanley's The Furys

- 3 Paradise Street Blues: Malcolm Lowry's Liverpool

- 4 ‘Unhomely Moments’: The Fictions of Beryl Bainbridge

- 5 A Man from Elsewhere: The Liminal Presence of Liverpool in the Fiction of J.G. Farrell

- 6 The Figure in the Carpet: An Interview with Terence Davies

- 7 ‘Every Time a Thing Is Possessed, It Vanishes’: The Poetry of Brian Patten

- 8 Finding a Rhyme for Alphabet Soup: An Interview with Roger McGough

- 9 Rewriting the Narrative: Liverpool Women Writers

- 10 Jumping Off: An Interview with Linda Grant

- 11 Ramsey Campbell's Haunted Liverpool

- 12 ‘We Are a City That Just Likes to Talk’: An Interview with Alan Bleasdale

- 13 ‘Culture Is Ordinary’: The Legacy of the Scottie Road and Liverpool 8 Writers

- 14 ‘I've Got a Theory about Scousers’: Jimmy McGovern and Lynda La Plante

- 15 Manners, Mores and Musicality: An Interview with Willy Russell

- 16 Subversive Dreamers: Liverpool Songwriting from the Beatles to the Zutons

- 17 Putting Down Roots: An Interview with Levi Tafari

- 18 ‘Out of Transformations’: Liverpool Poetry in the Twenty-first Century

Introduction: Sounding Liverpool

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- Dedication

- Introduction: Sounding Liverpool

- 1 George Garrett, Merseyside Labour and the Influence of the United States

- 2 ‘No Struggle but the Home’: James Hanley's The Furys

- 3 Paradise Street Blues: Malcolm Lowry's Liverpool

- 4 ‘Unhomely Moments’: The Fictions of Beryl Bainbridge

- 5 A Man from Elsewhere: The Liminal Presence of Liverpool in the Fiction of J.G. Farrell

- 6 The Figure in the Carpet: An Interview with Terence Davies

- 7 ‘Every Time a Thing Is Possessed, It Vanishes’: The Poetry of Brian Patten

- 8 Finding a Rhyme for Alphabet Soup: An Interview with Roger McGough

- 9 Rewriting the Narrative: Liverpool Women Writers

- 10 Jumping Off: An Interview with Linda Grant

- 11 Ramsey Campbell's Haunted Liverpool

- 12 ‘We Are a City That Just Likes to Talk’: An Interview with Alan Bleasdale

- 13 ‘Culture Is Ordinary’: The Legacy of the Scottie Road and Liverpool 8 Writers

- 14 ‘I've Got a Theory about Scousers’: Jimmy McGovern and Lynda La Plante

- 15 Manners, Mores and Musicality: An Interview with Willy Russell

- 16 Subversive Dreamers: Liverpool Songwriting from the Beatles to the Zutons

- 17 Putting Down Roots: An Interview with Levi Tafari

- 18 ‘Out of Transformations’: Liverpool Poetry in the Twenty-first Century

Summary

In the year that the city celebrates its 800th birthday, followed in 2008 by its designation as ‘European Capital of Culture’, the question is not whether there needs to be a book that examines the history and identity of literature from Liverpool but why that book should choose to concentrate on writing from the last eighty years. The latter is easier to address. Though notable writers such as William Roscoe (1753–1881), Felicia Hemans (1793–1835) and Arthur Clough (1819–61) were born in Liverpool, the city was from the late seventeenth to the early twentieth century more associated with trade than art. The origins of this reputation make for uncomfortable reading. In 1699, the same year as its first slave ship, the Liverpool Merchant, set sail for Africa, where it picked up a ‘cargo’ of 220 Africans who were later ‘deposited’ in Barbados, Liverpool was afforded parish status by an Act of Parliament. Significantly, one of the movers behind the separation of Liverpool from the parish of Walton-on-the-Hilll, Sir Thomas Johnson, one of the partowners of the Liverpool Merchant, became known in his own lifetime as ‘the founder of modern Liverpool’. The slave trade was to provide the financial impetus that allowed the city not only to cement its position within Britain but to grow in international influence and prestige. By the close of the eighteenth century, Liverpool controlled over 41 per cent of European and 80 per cent of Britain's slave commerce.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

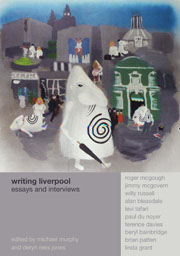

- Writing LiverpoolEssays and Interviews, pp. 1 - 28Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2007