Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 1 Popular politics and resistance movements in South Africa, 1970–2008

- 2 The Durban strikes of 1973: Political identities and the management of protest

- 3 ‘There's more to it than slurp and burp’: The Fatti's & Moni's strike and the use of boycotts in mass resistance in Cape Town

- 4 The role of the African National Congress in popular protest during the township uprisings, 1984–1989

- 5 Strategies of struggle: The Nelson Mandela campaign

- 6 From removals to reform: Land struggles in Weenen in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

- 7 From popular resistance to populist politics in the Transkei

- 8 ‘It's a beautiful struggle’: Siyayinqoba/Beat it! and the HIV/AIDS treatment struggle on South African television

- 9 The Nelson Mandela Museum and the tyranny of political symbols

- 10 Black nurses’ strikes at Baragwanath Hospital, Soweto, 1948–2007

- 11 The ‘New Struggle’: Resources, networks and the formation of the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) 1994–1998

- 12 New social movements as civil society: The case of past and present Soweto

- 13 ‘Phansi Privatisation! Phansi!’: The Anti-Privatisation Forum and ideology in social movements

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

7 - From popular resistance to populist politics in the Transkei

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 1 Popular politics and resistance movements in South Africa, 1970–2008

- 2 The Durban strikes of 1973: Political identities and the management of protest

- 3 ‘There's more to it than slurp and burp’: The Fatti's & Moni's strike and the use of boycotts in mass resistance in Cape Town

- 4 The role of the African National Congress in popular protest during the township uprisings, 1984–1989

- 5 Strategies of struggle: The Nelson Mandela campaign

- 6 From removals to reform: Land struggles in Weenen in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

- 7 From popular resistance to populist politics in the Transkei

- 8 ‘It's a beautiful struggle’: Siyayinqoba/Beat it! and the HIV/AIDS treatment struggle on South African television

- 9 The Nelson Mandela Museum and the tyranny of political symbols

- 10 Black nurses’ strikes at Baragwanath Hospital, Soweto, 1948–2007

- 11 The ‘New Struggle’: Resources, networks and the formation of the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) 1994–1998

- 12 New social movements as civil society: The case of past and present Soweto

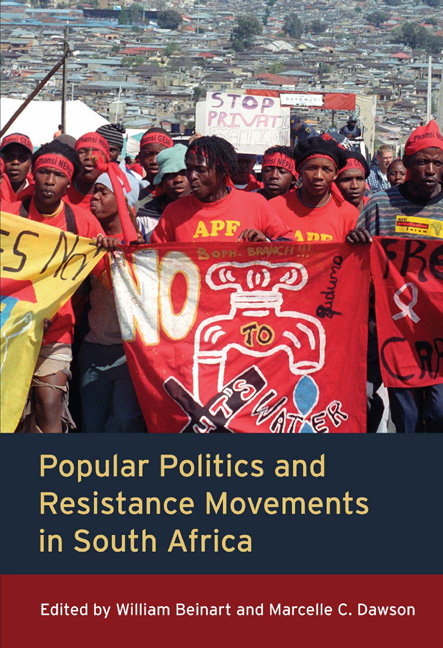

- 13 ‘Phansi Privatisation! Phansi!’: The Anti-Privatisation Forum and ideology in social movements

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Introduction

Of all the rural rebellions that broke out in South Africa in the middle of the twentieth century, the 1960 Pondoland revolt was the largest and most celebrated. Like the Sekhukhuneland rebellion, it was in part a ‘last ditch defence of land and cattle’ – arguably the end of a sequence of popular struggles by rurally based peasants and migrants against state intervention into their land and livelihoods. The revolts had been provoked by the apartheid government's so-called Betterment or Rehabilitation policies of the 1940s and 1950s that attempted to induce economic development by forcibly reordering rural society. Equally contentious were the state's attempts to reshape and control chieftaincy in the Bantu authorities system. Historians have recognised that traditional authorities did not die in twentieth-century South Africa, despite the long history of colonisation. Rural resistance reflected the still ‘pulsating remains of African kingdoms’. In some contexts there were direct connections between rural revolts and nationalist movements. But there were also tensions: rural resistance could be mobilised around local interests and ethnic identities that were uncomfortable for more modernising nationalists.

The historiography on the rebellions is growing. Yet the question remains: what happened afterwards, when rural communities were more fully incorporated into the state, as peasant production eroded and the grasp of government extended over rural regions? The overwhelming answer by historians has been that the homeland governments in South Africa were essentially dependent on Pretoria, which devolved power to reactionary, government-appointed chiefs as the basis for the fiction of homeland independence. Furthermore, the growth of the homeland state crystallised class divisions – the fault line lying between increasingly impoverished rural communities and the corrupt, comprador elite, centred round the chieftaincy, who enjoyed access to the goods of government. The 1980s saw anomic, runaway youth revolts in rural areas against the collaborating chiefs and Bantustan establishment, but the African National Congress (ANC) leadership negotiated with the pillars of the old, corrupted regimes in the 1990s. This account resonates with Mamdani's analysis of the legacy of late colonialism in Africa. In an argument that draws on Ranger's ideas about the ‘invention of tribalism’, Mamdani suggests that the authority of the colonial/ apartheid state was extended through its alliance with the local chieftaincy. This left a legacy of decentralised despotism – a mode of rule that has remained unbroken, despite the best attempts of post-colonial governments.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Popular Politics and Resistance Movements in South Africa , pp. 141 - 160Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2010