Book contents

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Disability

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Disability

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies

- 1 Introduction

- Part I Across Literatures

- Part II Across Critical Methods

- Recommended Reading

- Index

- Cambridge Companions to …

- References

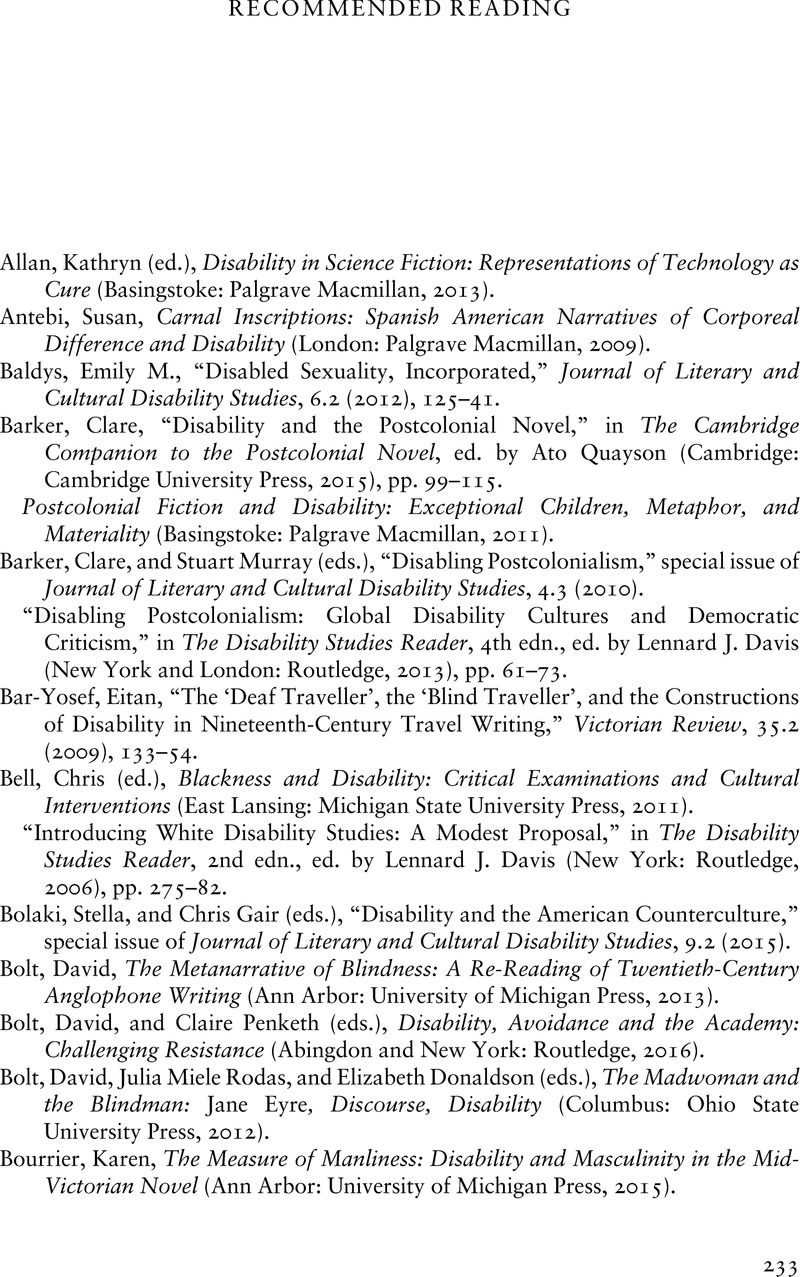

Recommended Reading

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 December 2017

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Disability

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Disability

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies

- 1 Introduction

- Part I Across Literatures

- Part II Across Critical Methods

- Recommended Reading

- Index

- Cambridge Companions to …

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Disability , pp. 233 - 242Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017