Conclusion: Saddening the Green

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 October 2019

Summary

Sweet smiling village, loveliest of the lawn,

Thy sports are fled and all thy charms withdrawn;

Amidst thy bowers the tyrant's hand is seen

And desolation saddens all thy green …

— Oliver Goldsmith, ‘The Deserted Village’What does the lawn want?

At the end of this book it is appropriate to return to a theoretical proposition that has been central to it: W. J. T. Mitchell's proposal that landscape should be considered a verb. I have argued that this notion holds promise for studying the landscape, especially as Mitchell has revised the verb concept in the second edition of Landscape and Power (2002) and What Do Pictures Want? (2005).

First, implicit in the shift from landscape-as-noun to landscapeas- verb is a move from meaning to doing. This book has asked not what the lawn – or, for that matter, the mine dump, the suburban swimming pool, the safari sunset, the hills of Marikana – means, or what it is, but rather what it does; what that doing does, what possibilities it opens up or closes down. Along these lines, the book has been asking what the lawn makes possible. Clearly, the lawn often forms the grounds of possibility for making certain claims on a respectable subjectivity. Put another way, the lawn is one of the grounds for the constitution of civilised human and non-human subjects. What the lawn does not provide grounds for is political annunciation. It reduces the political problem of land to the aesthetic question of landscape, thereby obscuring issues of ownership, labour, belonging and redress. The lawn is an ‘anti-politics machine’ (Ferguson 1990), distributing modernity but denying its own politics.

One key aspect of the lawn's modernity is the creation of regularity – the production of standardised, internationally (and especially nationally) recognised landscapes with historically established rules, by which it is possible to assess their conformity to norms. Here we are required to ask: what other kinds of diversity are denied, disallowed and misrecognised by this attempt at structural regularity? The lawn attempts to dematerialise itself, or deny its own materiality – as if it were not made out of living matter, as if there is no labour and no consequences to lawning a space – which is evident in how often it is described as clean, sanitary, flat, neat.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

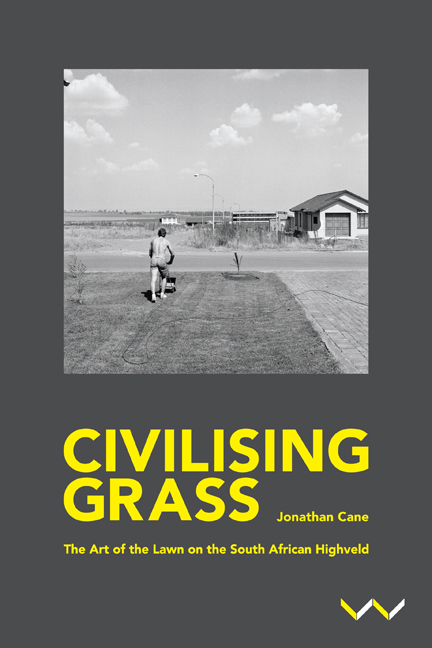

- Civilising GrassThe Art of the Lawn on the South African Highveld, pp. 173 - 182Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2019