Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Solidarity, Social Norms, and Uncle Tom

- 2 Uncle Tom: 1865–1959

- 3 The Unwitting Pioneers

- 4 Uncle Tom: 1960–1975

- 5 No Man Was Safe

- 6 Uncle Tom Today: 1976–Present

- 7 So What About Clarence?

- 8 The Curious Case of Uncle Tom

- 9 What Now, Uncle Tom?

- Final Address

- Index

- References

3 - The Unwitting Pioneers

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 May 2015

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Solidarity, Social Norms, and Uncle Tom

- 2 Uncle Tom: 1865–1959

- 3 The Unwitting Pioneers

- 4 Uncle Tom: 1960–1975

- 5 No Man Was Safe

- 6 Uncle Tom Today: 1976–Present

- 7 So What About Clarence?

- 8 The Curious Case of Uncle Tom

- 9 What Now, Uncle Tom?

- Final Address

- Index

- References

Summary

Uncle Tom and the Negro Leader

Racial treachery must be uncovered and punished. This gospel flowed through the veins of the black community. Blacks, therefore, intently monitored the race’s most visible – the famous. Many take their cues from, or at least are influenced by, the most acclaimed and prominent members of their group. If black elites, so to speak, violated racial loyalty norms with impunity, the masses were increasingly likely to stray too. Their heightened prominence, moreover, amplified the damage of betrayal. If a renowned black figure publically endorsed Jim Crow, for instance, those frightful words could crush blacks’ morale. And foes of racial progress would appropriate the comments to defend the empire that white supremacy built. The racial treachery of famous blacks, in short, could imperil the race’s interests in exaggerated ways. Thus, policing racial loyalty carried obvious benefits. By proscribing certain behaviors and actions, blacks helped prod the group’s most visible persons into being productive racial agents and stop the spread of the disease that all Uncle Toms carry. Perhaps this explains why famous blacks during this period were victimized more by destructive norms than the black masses. Indeed, this chapter contains more unwarranted Uncle Tom denunciations than the previous. The over-vigilance is understandable, but must be rejected. Studying the mistakes of yesteryear can guide subsequent generations.

The famous blacks who most needed monitoring were black leaders. Here, a black leader refers to someone whose voice has special influence in dialogues, whether national or local, concerning racial uplift. A leader who violated constructive norms imperiled the race’s legal interests and ability to influence the debates that drove public policy. Blacks, consequently, had to ensure their absolute dedication to the cause of racial progress.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

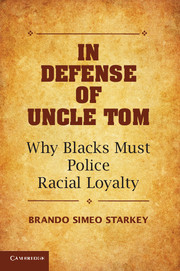

- In Defense of Uncle TomWhy Blacks Must Police Racial Loyalty, pp. 106 - 157Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015