Peacebuilding became a signature undertaking of the international community in the post-Cold War era. As the number of United Nations-led peace operations proliferated globally, so, too, did study of these interventions, which developed along three major avenues of analysis. First, there are numerous case study-based assessments of specific peacebuilding attempts. These are extremely rich in empirical detail, many penned by peacebuilding scholar-practitioners reflecting on their experiences in different countries.Footnote 1 The best of these accounts provide fascinating narratives of how domestic elites interacted with peacebuilders during implementation of particular interventions; however, they do not typically attempt to reach any broader generalizations about the patterns of peacebuilding. A second body of work focuses more on the machinery and mechanisms of peacebuilding approaches themselves, offering detailed interpretation of operational mandates that focus on how the specifics of intervention – such as mission scope, size, multidimensionality, mechanisms of implementation, and so on – affect outcomes.Footnote 2 These studies tend to be geared toward identifying the technocratic challenges associated with peacebuilding and thereby generating targeted and informed measures for improving practice. The third body of scholarly work on peacebuilding has focused on more theoretically motivated analyses of international interventions. Within this strand of writing, both case-oriented and quantitative empirical studies have aimed to offer generalized insights on the way in which specific components of interventions – such as the degree and scope of the mandate, often termed the “footprint” – and some consideration of the broader conditions under which they are implemented affect the relative success of peacebuilding interventions. The standard analytical approach is thus evaluative and variable-centered, based on a probabilistic logic – delving into what mission parameters and contextual factors condition the likelihood of success.Footnote 3

Collectively, the scholarship treats peacebuilding interventions, in effect, as exogenous processes that are applied in post-conflict countries and thus measures governance outcomes in these countries against the yardstick of the modern political order that is sought through peacebuilding. The UN's transitional governance approach to transformative peacebuilding structures the pursuit of rule-bound, effective, and legitimate governance by guiding domestic political elites through a series of choices about institutional architecture. This process, as it is designed, results in new administrative structures and constitutional arrangements that are tailored to local contexts and aspire to the highest international standards of democratic governance. Accordingly, peace operations are extolled as relative successes if they end with some degree of effective and legitimate governance being successfully transplanted into their host countries via this method of institutional engineering.

Yet, in one post-conflict country after another, initial euphoria at the successful holding of elections and design of the formal institutions for democratic governance has turned over time into relative dismay at the poor governance outcomes that arise in the aftermath of intervention. The transitional governance approach achieves some important successes in establishing the formal institutional infrastructure of legitimate and effective governance. The part of the story that has been missing is that the domestic political dynamics set in motion by the peace operation itself hamper the meaningful longer-term consolidation of governance outcomes in specific patterns. This chapter, like other work before it, focuses squarely on the peacebuilding interventions implemented by the United Nations in tandem with domestic counterparts. It does so, however, through a historical institutionalist lens that identifies the patterns in how domestic political elites interact with peacebuilding interventions to iteratively reshape the transitional governance process and actively engage in building neopatrimonial instead of modern political order. The case-centered, conjunctural logic helps to better identify the causal mechanisms that contribute to longer term governance outcomes.

Moreover, this chapter's focus on the transitional governance experiences of the three countries demonstrates the significance of temporal sequence. The manner in which peacebuilding contributes to the building of political order is shown to be path-dependent. The phenomenon of increasing returns is clearly on display, such that previously available options and strategies – for both domestic elites and international actors – recede once certain choices are made. In turn, political actors can be seen to be reorganizing their strategies around the path taken. The fact that temporal location – when certain things occur or choices are made, relative to others – matters is also made especially clear in terms of the significance of the early selection of specific counterparts for the transitional governance process.Footnote 4 In short, this chapter highlights how decisions made for the sake of expedience and practicality have long-term political consequences. Foregone alternatives that may have been more desirable become increasingly difficult to reach as time passes and countries move along the peacebuilding pathway.

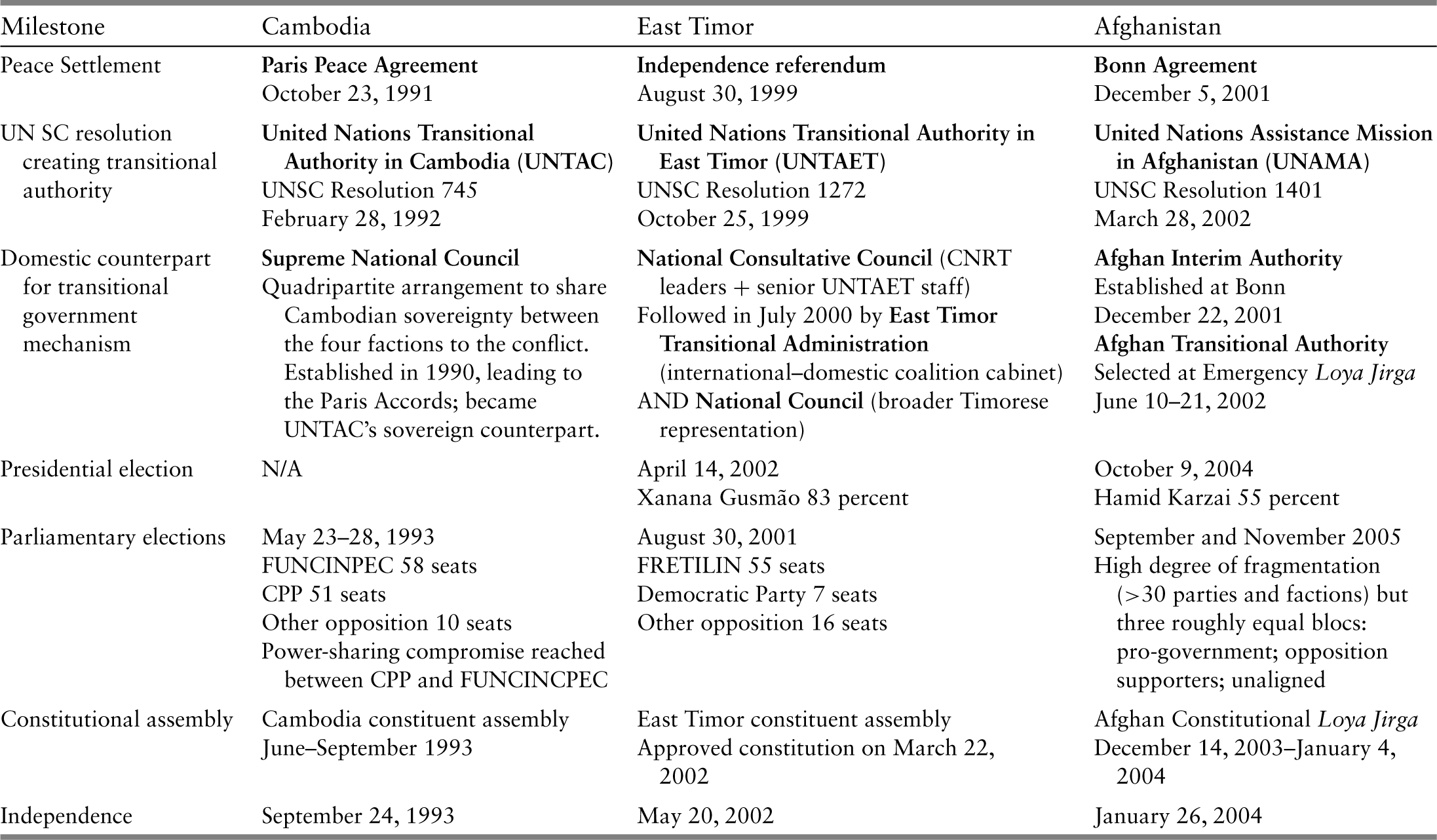

Peacebuilding through transitional governance rests upon two distinct characteristics that contribute to unintended governance consequences in post-conflict countries. Underpinning the transformative model, first, is the implicit assumption that statebuilding and democracy-building are mutually reinforcing processes that can be advanced fruitfully in post-conflict countries through external peace operations. Second, the transitional element of the intervention, by which the United Nations takes on some degree of executive state function for a two-to-three-year period to ensure basic governance needs are met, requires the identification of a domestic counterpart with which the UN can govern in tandem. This chapter demonstrates, through an examination of the interventions in Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan, how the interplay between these two hallmarks of the transitional governance approach undermine the basic objective of transformative peacebuilding, which is establishing the basis for rule-bound, effective, and legitimate political order. The three cases illustrate how the transitional governance experience itself empowers specific domestic elites, conferring legitimate authority upon them and offering them financial resources and sources of patronage. The elections that mark the end point of international interventions, in turn, empower these elites to occupy the legitimate political space even as they offer a focal point for the consolidation of hierarchical patron–client networks.

This dynamic becomes evident over the course of transitional governance, as the series of facilitated decisions it embodies alter the post-conflict political order in subtle, yet lasting ways. This chapter illustrates how the principles underpinning transformative peacebuilding are more deeply flawed because they also fail to take into account how domestic political elites will use the resources bestowed by the international community in their pursuit of forging neopatrimonial political order. It focuses on the international peacebuilding interventions in Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan, splitting the analysis of each case into two sections. First, the transitional governance period is portrayed as, at heart, a process of institutional engineering, where the interaction between domestic elites and international peacebuilders takes place, in many respects, as a series of negotiations around these institutions. Second, the first post-conflict election in each country is discussed. Serving as the end point of intervention, these elections are crucial, externally imposed moments of open political contestation – and their results confer lasting political advantages to those elites who claim victory in them.Footnote 5

The historical institutionalist lens offers a fruitful perspective to help make sense of what occurs over the course of these interventions. James Mahoney and Kathleen Thelen advance a theory of institutional change whereby actors motivated to change outcomes use different strategies to exploit the ambiguity in the interpretation of rules to their advantage by redeploying the rules to suit their own purposes or changing those rules outright.Footnote 6 “Insurrectionaries” take the most obvious and visible route to change institutions, actively mobilizing against them. But three other sets of strategies offer fine characterizations of the myriad more subtle and yet equally effective ways in which elites can and do operate within the neopatrimonial hybrid between patrimonial and legal-rational forms of authority. “Subversive” actors conform in the short run to the current system, while biding their time to achieve their longer-term change goals. “Parasitic” actors exploit the current set of institutions even as they depend on those institutions to achieve gain. “Opportunistic” actors thrive in conditions of institutional ambiguity, successfully exploiting the numerous possibilities within the prevailing system to advance their goals. This chapter illustrates how the winning elites in the three cases considered here have used all of these institutional change agent strategies in obtaining their preferred form of political order.

Transitional Governance in Cambodia

The Cambodian transitional governance experience was the first of its kind, with the UN being responsible for holding a national election as well as governing the country in collaboration with counterparts.Footnote 7 With an outlay of $2.3 billion over five years and 22,000 people deployed to the mission, it dwarfed spending on any previous UN peace operation.Footnote 8 Two issues are evident when analyzing the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC). First, the principle of power-sharing among the four Cambodian factions that was embodied in the Paris Peace Agreement and re-emphasized in UNTAC's mandate proved a red herring, since the various Cambodian factions were not truly reconciled to the agreement and refused to cooperate with UNTAC's attempts to implement its principles. Second, as a result, one particular faction – the State of Cambodia (SOC) governing regime, led by Hun Sen – was allowed to maintain its grip on the state apparatus. Thus entrenched, even defeat in the first election was not enough to dislodge this regime's hold on power. The UNTAC experience illustrates vividly the basic tension between statebuilding and democratization embodied in the transitional governance approach. The need to continue governing the country meant the UN had to rely on the SOC. The SOC, in turn, was able to parlay its control over the state into a set of political resources that enabled it to perform better than expected in the election and its immediate aftermath.

The Paris Peace Agreement signed by the four Cambodian factions in October 1991 established the two major features of the peace settlement. First, the agreement was the genesis of UNTAC, the peacebuilding operation mandated several months later to implement the peace settlement.Footnote 9 UNTAC's wide-ranging mandate gave the UN a brand new role and scope of action in a peacebuilding intervention. Second, the Paris accords also mandated a particular role for the Supreme National Council (SNC). This quadripartite body was created in the run-up to the final peace agreement to achieve binding consensus among the four Cambodian parties. With the peace settlement concluded, the SNC became the ongoing institutional manifestation of that temporary consensus. It comprised a membership of 13 individuals representing each of the four parties, with Prince Sihanouk named as the supposedly neutral president of the group; the six SOC delegates were loyal to Hun Sen's clique within the regime.Footnote 10 It was endowed with Cambodian sovereignty and authority and it would govern the country as UNTAC's parallel domestic counterpart, acting as an advisory body in the transitional governance period before elections were held. Doyle notes that the Security Council's endorsement of the SNC helped, in turn, to legitimize its delegation of authority for administrative and electoral affairs to UNTAC.Footnote 11

UNTAC represented a new, transformative approach to peacebuilding. It was the first UN peace operation to be mandated with the organization and supervision of an electoral process from start to finish. Its roles on this front included promulgating electoral laws, organizing the polling and monitoring, educating Cambodians about their new electoral rights, and certifying the elections as free and fair. Along with its other responsibilities – including the civil administration component, discussed below; a military component monitoring the ceasefire and demobilization of the factions’ armed wings; a civilian police component; a refugee repatriation component; and a human rights component – the electoral component made UNTAC larger than any previous peacekeeping operation and the most intrusive operation yet in the internal affairs of a member state.Footnote 12

UNTAC also assumed an unprecedented degree of transitional administrative authority in Cambodia, granted with the formal consent of the four factions in the Paris Agreement in an attempt to ensure a neutral political environment for the conduct of the first elections. UNTAC's central mandate was to help control the governance of Cambodia in the transitional period. The large Civil Administration Component of the operation handled this dimension of the peacebuilding strategy by monitoring and supervising existing bureaucratic structures in five designated key areas of civil administration – defense, public security, finance, information, and foreign affairs.Footnote 13 This combination of administrative and electoral organization functions makes Cambodia the first post-conflict country in which the UN implemented a strategy of peacebuilding through transitional governance.

As UNTAC worked to implement its mandate, it became clear that the peacebuilding process was compromised by the competing conceptions among the four Cambodian parties as to the nature of the intervention. The true consent from each of those parties to the peace settlement and the intervention was tenuous at best. Those inconsistent commitments translated directly into problems for the institutional mechanisms of transitional governance in Cambodia. Each of the parties to peace, for example, viewed the relationship between UNTAC and the SNC in a different way.Footnote 14 A major point of contention was the role envisioned for Hun Sen's State of Cambodia (SOC) and how it would interact with UNTAC and the SNC in which it represented just one of the four distinct sets of Cambodian preferences. The SOC itself, relying on its control over the apparatus of both central and subnational government, essentially continued to emphasize its own domestic governing authority. By treaty, however, it was the SNC that officially embodied Cambodian sovereignty. For the Khmer Rouge, the KPNLF, and FUNCINPEC, the SNC – with their participation – was the only legitimate source of political power in Cambodia. In their conception, UNTAC would act on behalf of the SNC, thereby rendering Hun Sen's SOC relatively powerless. Prince Sihanouk was given special authority in the SNC under the peace accords in the hope that he could bolster UNTAC's stance and help push the factions toward compliance. Yet he turned out to be mostly detrimental to the process, hesitating to break deadlocks but insisting that the UN defer to him. UNTAC, in line with the Permanent Five's initial design of the arrangement, envisioned the SNC as an important reconciliation body that would help it make and implement important decisions. When it was proven wrong on that front, UNTAC had to assume more of the responsibility itself.

These competing visions of how transitional governance would unfold meant that the concerned parties never reached agreement on how to implement the peacebuilding process as envisioned by the Paris Peace Agreement. Frederick Brown and David Timberman observe that UNTAC had essentially been “charged with the task of enforcing an extraordinarily complex, time-phased scenario predicated on an environment of conciliation and compromise among the Khmer parties that did not, in fact, exist.”Footnote 15 Many have argued, in addition, that the Permanent Five did not give UNTAC the necessary teeth to achieve its objectives, especially in the realm of day-to-day administration. UNTAC was supposed to ensure a neutral political environment by supervising the five designated key areas of civil administration and thereby preventing any of the factions – particularly the SOC – from using government resources to influence the elections. The mandate was to “control” Cambodia and the four factions through supervision, rather than actually govern the country. Yet the framers of the Paris Peace Agreement and the UNTAC mandate did not specify how this should be done, leaving it to the discretion of UNTAC's command, led by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG), Yasushi Akashi. Many in the United Nations felt that pushing the incumbent SOC regime too far on the issue of political neutrality would derail the peace process. In turn, the SOC refused to relinquish its control of the state – in practice, it “simply administered around UNTAC.”Footnote 16 An UNTAC progress report found, for example, that high-ranking SOC officials gave the ministries and provincial administrations instructions in how not to cooperate with UNTAC.Footnote 17 This failure to pry away the SOC's grip on the state apparatus later fed into today's relatively poor governance outcomes in Cambodia. It became apparent closer to the elections that UNTAC's control over the other three factions was negligible as well.

The Cambodian Elections of 1993

In the face of these challenges with regard to transitional governance, UNTAC essentially abandoned its attempts to implement the comprehensive Paris peace settlement. Midway through the peace operation toward the end of 1992, supported by a series of UN Security Council resolutions, it reformulated its mandate to focus on the election and create a legitimate Cambodian government. UNTAC did indeed successfully hold Cambodia's first democratic national election in May 1993. Analysts assessing UNTAC close to the end of its tenure in 1993 concluded that of all its various dimensions its Electoral Component was probably the most successful.Footnote 18 Today it is clearer that while this may have been true in a technical sense – in terms of registering voters and holding a relatively conflict-free, high-turnout election, even in the face of a high degree of voter intimidation and harassment by the SOC and the Khmer Rouge – UNTAC failed, to a large degree, in reaching the objective of creating legitimate government as a central component of modern political order.

Subsequent problems of statebuilding and democratic consolidation can be traced back to conditions at the time of the first election and the fact that the effort dedicated to the electoral process masked the deep antagonisms in the Cambodian polity. In early 1993, the Khmer Rouge withdrew entirely from the electoral and peacebuilding process, leaving the capital city, refusing to disarm and demobilize as agreed, and preventing UNTAC from entering the zones of the country it controlled.Footnote 19 It mounted a campaign of obstruction against the other Cambodian parties and UNTAC and succeeded in generating an atmosphere of instability and violence around the electoral process. Perversely, the SOC's political fortunes rose as there was an increase in Khmer Rouge-perpetrated electoral violence – in a context of political instability, it was seen as the only party with the armed forces capable of containing the Khmer Rouge and maintaining political order. Indeed, it used this reason to delay demobilizing its own armed forces. At the same time, however, popular resentment about the SOC's corrupt practices was brewing.Footnote 20 The Khmer Rouge's suspicion of the SOC – their expressed reason for reneging on the Paris Peace Agreement – was not entirely unreasonable, considering the trajectory taken by the CPP and Hun Sen to their later levels of political hegemony. At the time, however, UNTAC, and particularly Akashi, viewed the Khmer Rouge as the one true threat to the peace process, and proceeded to systematically marginalize the radical party from the elections to prevent it from derailing the entire peace.Footnote 21

A successful election became Akashi's single-minded priority in the desire to be able to claim the UNTAC mandate had been achieved, especially in light of the relative failure to demobilize and adequately supervise the Cambodian factions.Footnote 22 Despite warnings from UNTAC officials and others, Akashi did not perceive the SOC as a potential spoiler and he was therefore caught entirely off-guard when it explicitly began undermining the peace process immediately after the first elections.Footnote 23 The SOC's participation in the elections was crucial to UNTAC's success as Akashi came to define it. Yet that meant that he failed to use the leverage granted to UNTAC in the Paris Peace Agreement to reduce the SOC's grip on the administrative organs of state, in retrospect the most intractable future impediment to legitimate governance in the country. The head of UNTAC's administration, Gerald Porcell, lamented as he resigned in protest in February 1993 that as long as UNTAC lacked “the political will to apply the peace accords, its control cannot but be ineffective.”Footnote 24

In effect, Akashi's strategy for dealing with the Khmer Rouge strengthened the hand of the SOC, making it by far the strongest faction on the Cambodian political scene, militarily, politically, and administratively. As the UNTAC Commander John Sanderson observed, “it was not the Khmer Rouge, but rather the SOC, which had the capacity to undermine the election or to overturn the verdict of the people.”Footnote 25 Even before the 1993 election, the SOC had manipulated the terms of the peace agreement to its own advantage: the separation of the State of Cambodia (SOC) and its political party, the Cambodian People's Party (CPP), was in name only and hardly enforceable. During this period, the SOC made continuous efforts to interfere with the campaigning of other parties and practiced widespread voter intimidation and buyoffs, as well as violence in the run-up to the elections that included the killing of political activists from the other parties.Footnote 26 UNTAC found it impossible to separate the government's resources, in the hands of the SOC, from the funds used by the Cambodian People's Party (CPP), the political party that the governing regime formed in 1991 just before the peace accords were signed. UNTAC investigations found that the SOC state apparatus was often used to campaign on behalf of the CPP, for example.Footnote 27 To those who controlled the State of Cambodia and the apparatus of government, defeat in the country's first election was unimaginable and they did everything they could to ensure victory.

The elections, held from May 23–28, 1993, although hardly held in a “neutral political environment,” were successful in terms of the 90 percent voter turnout and were declared free and fair by UNTAC and other international observers.Footnote 28 The results were surprising and unambiguous: FUNCINPEC won 45 percent of the vote and the CPP came second with 38 percent, translating into 58 and 51 seats, respectively, in the 120-member constituent assembly that was to draft and adopt a new constitution before evolving into the national legislature. FUNCINPEC's leader, Prince Norodom Ranariddh, was Sihanouk's son and the heir to his political power base, and many observers attributed FUNCINPEC's victory to a nostalgic, nationalist vote for the monarchy. What followed immediately after the elections was extraordinary and yet a characteristic marker of the future direction of the Cambodian political scene – as well as a fascinating illustration of what happens when there is an imbalance between the formal writ of power and its informal, or actual, exercise. The CPP simply refused to acknowledge FUNCINPEC's electoral victory and actively subverted it. It took an elaborate series of steps to instead entrench itself in power, including accusing the UN of massive fraud, roping in Sihanouk, and blackmailing the opposition with a short-lived secession and increased violence. As Ranariddh realized that the CPP would never hand over full administrative power FUNCINPEC was forced to compromise and agreed, in a deal brokered by Sihanouk, to share power equally with the CPP in the new interim government. UNTAC was left a bystander in these domestic political maneuverings and, subsequently, the CPP's heightened power made UNTAC helpless to block its bid for hegemony. Akashi supported the power-sharing solution, believing at the time that failure to compromise would undermine the triumph of having held the election. Indeed, he believed the “practical wisdom” combined FUNCINPEC's political power and victory with the administrative power and experience of the CPP.Footnote 29

While many, Cambodians and international officials alike, were dismayed that the final arrangement did not truly reflect FUNCINPEC's electoral victory, there was little question that “the compromise aptly reflected the administrative, military, and even financial muscle of the CPP.”Footnote 30 Sihanouk and Ranariddh even agreed to the CPP's stipulation that all votes in the new Assembly be passed by a two-thirds majority, which ensured that the CPP's consent would be needed in any legislation and hence enabled it to continue to dominate the business of government. In practice, moreover, the CPP retained control of all the provinces, even those it had lost in the election. In many central ministries, the personnel and policies remained unchanged from those of the SOC. Although the process of army consolidation began, the CPP retained control over the police. The SOC/CPP regime thus maintained its stranglehold on the state apparatus and would soon leverage this essential arena of strength into an outright power grab. The Khmer Rouge, by this point completely marginalized in the political process, refused to accept the new government. Cambodia's new combined army attacked Khmer Rouge positions all over the country and the government appealed to Khmer Rouge soldiers to lay down their arms, which many did. Although a rump Khmer Rouge insurgency continued for a few more years, its campaign for power was effectively ended with the 1993 electoral process.

The Paris Peace Agreement and the transitional process they initiated themselves shaped the consolidated governance outcomes to ensue in Cambodia. From the beginning, the international community seemed resigned to allowing the State of Cambodia regime to retain its control of the country. In the words of Brown and Timberman: “The implicit quid pro quo of the Paris Accords in 1991…had been that the incumbent CPP would have a fair shot at political dominance if it would go along with the rules of the game of UNTAC and abide by the results of the election.”Footnote 31 Even when the CPP did not win, however, its lukewarm and inconsistent participation in the UN transitional governance process was enough to convey upon it the stamp of legitimacy it had lacked during its previous period of rule. In turn, as the next chapter demonstrates, the convoluted power-sharing arrangement that resulted from the election created two separate governments led by Ranariddh and Hun Sen who had been named first and second prime ministers.

The CPP's push to restore its political dominance and subvert the unstable power-sharing arrangement became the defining characteristic of political jockeying in Cambodia over the next decade. Several Cambodia experts warned in the mid-1990s of the CPP's and Hun Sen's “creeping coup,”Footnote 32 which later proved prescient. Brown and Timberman blame the international community for “retreat[ing] from its commitment to establishing a genuinely legitimate government when it acquiesced to Hun Sen's demands for power sharing” after the 1993 election.Footnote 33 They go on to observe that by effectively allowing Hun Sen, with Sihanouk's complicity, to override the electoral results, the international community became party to an act that broadcasted the message that power politics would continue to prevail in Cambodia over the rule of law and the electoral process. Yet, at the time, the CPP–FUNCINPEC coalition seemed to many to be the only option in an environment in which FUNCINPEC had electoral legitimacy but the CPP had institutional and military strength.

A Constituent Assembly committee drafted a constitution in almost total secrecy, with barely any consultation with either UNTAC or Cambodian civil society groups, resulting in a document that was written and favored by the CPP, albeit one that was liberal in spirit.Footnote 34 The new permanent government would include two co-prime ministers and the two-thirds voting majority was also retained, both at the demand of the CPP and against FUNCINPEC's wishes. Ministerial posts and governorships were divided among the two parties. In reality, however, the CPP's continued control over the bureaucracy, army, and police was a locus of political power that simply outweighed FUNCINPEC's electoral victory. In terms of democratic consolidation and how power was distributed across the political system, the elite bargaining over the interim and then permanent arrangements was far more important than the elections themselves. The CPP, having used its leverage to get a power-sharing compromise and stack the institutional architecture in its favor, waited for its chance to seize power outright.

Transitional Governance in East Timor

The United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) represents the high-water mark of the transitional governance approach and its transformative peacebuilding aspirations. The international community spent $2 billion on the first five years of the Timorese peace operation and deployed more than 10,000 military and civilian personnel there; extraordinary figures for a country of fewer than one million people.Footnote 35 UNTAET was designated as the repository of East Timorese sovereignty until the country was made fully independent, in a mandate that represents the greatest degree of executive, legislative, and judicial authority a UN mission has exercised in a post-conflict nation to date.Footnote 36 The Cambodian experience represented the dire difficulties associated with pursuing effective and legitimate governance in a country where the parties were not truly reconciled. East Timor represents the more subtle and yet equally real complexities of attempting to transplant modern political order in a context of apparent elite consensus and a relative alignment with the objectives of the international community.

The Security Council mandate for UNTAET instructed the peace operation to guide East Timor to a state ready for independence.Footnote 37 Yet it provided no roadmap – along the lines of the Paris Peace Agreement for Cambodia, for example – for how to proceed or how to incorporate East Timorese participation during the process. UNTAET first addressed the governance of East Timor by directly assuming the bulk of administrative and executive functions, moving only in mid-2000 to begin the process of sharing and passing on authority to its Timorese counterparts.Footnote 38 UNTAET defenders have argued in retrospect that the transitional governance exercise adopted gradually increasing levels of East Timorese participation in decision-making processes over time. Yet the Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG), Sergio Vieira de Mello, himself acknowledged that increasing Timorese participation in the governance of the country was a process of “false starts and hard-won political accommodations.”Footnote 39

UNTAET's strategy was to emphasize regular consultations with a small group of core leaders from the National Council for Timorese Resistance (CNRT) – including, in particular, Xanana Gusmão, Bishop Carlos Belo, José Ramos-Horta, Mari Alkatiri (the leader of the FRETILIN cadre returned from exile in Mozambique), and Mario Carrascalão (a leading Timorese businessman who had served as governor of East Timor under the Indonesian authorities but was widely seen to have worked on behalf of the Timorese population during his governorship). These CNRT leaders were viewed by the UN as the authentic representatives of the people of East Timor and Gusmão was the undisputed first among equals. The head of the earlier UN Mission in East Timor (UNAMET), Ian Martin, wrote that the UN believed that Gusmão's direct participation was crucial: UN representatives saw that progress in the negotiations before the referendum was made only when Gusmão was present and the UN itself took big steps forward only after consulting him in his Jakarta prison cell.Footnote 40 Vieira de Mello later acknowledged that this elite consultation system, albeit well intentioned, did not go far enough and that its Timorese partners should have been brought on board earlier and should have been consulted more thoroughly and substantively on matters of policy formulation and implementation.Footnote 41 In contrast, for example, the World Bank was seen as rather more successful at including Timorese in both needs assessment and policy formulation, most notably in the Joint Assessment Mission that took place in October and November 1999 immediately after the referendum violence was ended in order to identify reconstruction and development priorities.Footnote 42

The timing and sequencing of the transitional governance process created some immediate challenges for future statebuilding and democratization prospects. Most observers agree that the slow pace of incorporating Timorese views and participation in government – a process that came to be called “Timorization” – was the most problematic aspect of the experiment, proving extremely troublesome for UNTAET's ability to govern and orchestrate a transition.Footnote 43 Here I contend, furthermore, that UNTAET's handling of the problem – especially the manner in which it chose its main counterparts – allowed the entrenchment of particular institutions and a certain pattern of political behavior that subsequently had adverse effects on democratic consolidation and governability in East Timor. Sue Ingram makes a similar argument, going so far as to contend that, in its lack of attention to forging a political settlement among Timorese elites, “UNTAET built the wrong peace.”Footnote 44 From this perspective, two things went wrong: not enough Timorese participation in government; and, when Timorization occurred, too much emphasis on just the CNRT and its elites, which prejudiced the political process in favor of FRETILIN leaders. Furthermore, a third dynamic emerged that is at the core of the tension between state- and democracy-building: the East Timorese elites’ near obsession with participation in the political arena meant that both they and UNTAET failed to emphasize the Timorization and renewal of the eviscerated state and administrative infrastructure.

No formal structures were built into UNTAET for East Timorese official or civil society participation – either in the electoral component or on the administrative side of the mission itself. The paradox surrounding participation was built into the very mandate of UNTAET.Footnote 45 Resolution 1272 stressed the need for UNTAET to “consult and cooperate closely with the East Timorese people”;Footnote 46 yet only after first vesting full sovereign powers in UNTAET and the Transitional Administrator, who was “empowered to exercise all legislative and executive authority; including the administration of justice.”Footnote 47 This formal contradiction could certainly have been resolved in practice, if Vieira de Mello and UNTAET had moved to build channels of participation into the mission – the mandate itself had given the Transitional Administrator the freedom to develop whatever necessary mechanisms for political consultation and even to move toward a dual-structure government. But Caroline Hughes notes that UNTAET's actions spoke for themselves when it acted first to organize itself and only then “reluctantly conceded the need to admit the Timorese elite to the circle of power,” much later moving to incorporate political actors from the grassroots.Footnote 48

UNTAET was thus originally extremely reluctant to incorporate East Timorese participation.Footnote 49 On the one hand, many UN and other expatriates working in East Timor came to the country believing the political system was a tabula rasa, and managed their dealings with the Timorese accordingly. This perception hardly did justice to the nuanced and freighted contemporary Timorese political landscape. On the other hand, there was a pervasive fear among UNTAET officials that by working too closely with specific Timorese political actors, they would prejudice the results of the all-important first election by privileging a particular group over others. In part due to the guiding principles and institutional culture of the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, UNTAET emphasized impartiality with respect to local contending factions over building local participation. On the ground, this translated into a great deal of ambivalence on UNTAET's part over its relationship with the CNRT and how deeply to include its participation in governing the country – in some instances UNTAET treated the CNRT as a political faction, in others as a vehicle for inclusive Timorese political participation.Footnote 50

The UN Department of Political Affairs, which had originally managed the Timorese peace process, had planned to include more specific provisions for Timorese participation by giving the Timorese political authority while the UN assumed legal and administrative authority and served in an advisory role.Footnote 51 This system would have matched more closely the relationship between UNTAC and the Supreme National Council in Cambodia. The Department of Political Affairs even proposed a fully dual-structure administration along with a specific electoral timetable to emphasize the transitional nature of the administration. But the final Department of Peacekeeping Operations proposal sent to the UN Security Council included neither the dual-state structure nor the timetable; instead, only consultative principles with unspecified mechanisms made it into the UNTAET mandate.

The mission was hence launched as a fully UN-staffed operation with no formal counterpart. Yet UNTAET found, upon its arrival, a natural group to act as its local counterpart. The CNRT had acted as the umbrella pro-independence organization during the course of the decades-long resistance, enjoyed considerable legitimacy from its symbolic role at the head of a popular and successful national resistance front, and had been the organizational driving force behind the pro-independence victory in the referendum. Xanana Gusmão continued to lead the CNRT, endowing it with his charisma and popular support – although FRETILIN leaders within the organization increasingly challenged his claim to speak for a unified CNRT. It also benefited from the extensive non-military network that was developed throughout the towns and villages of East Timor during the course of the resistance. The survival of CNRT and FRETILIN had depended on this network, which now translated into a formidable organizational presence that reached throughout the country. UNTAET could not hope to meet this de facto control in the field, even though it had de jure authority at the center. After Indonesian provincial administrators left East Timor in the wake of the referendum, the CNRT was the one organization with nationwide political reach in an eviscerated institutional state structure and acted in many areas as a de facto governmental authority over the country.Footnote 52

Furthermore, there was a natural political affinity between UNTAET and a major wing of the CNRT, in that both favored a “national unity” approach to politics and government that reflected their nervousness about open political competition.Footnote 53 CNRT elites, in particular, opposed political party development, fearing a return to the brief but violent civil war of 1975, which followed a period of nascent party development in East Timor and provided a pretext for Indonesia's invasion. Karol Soltan, the Deputy Director of UNTAET's Department of Political, Constitutional, and Electoral Affairs, remarked that he came to think of the fear of 1975 “as the greatest enemy of democracy in East Timor.”Footnote 54 The CNRT was predisposed toward a transitional arrangement before full independence: in the mid-1990s it had proposed as a political compromise a UN-supervised transition to independence as long as 11–13 years. Even in the wake of the August 1999 referendum, some CNRT leaders, including Gusmão himself, were still in favor of a relatively long, five-year UN-assisted transition to independence, and other East Timorese leaders were amenable to the final two- to three-year solution as designed.Footnote 55 Yet while the CNRT did become UNTAET's de facto interlocutor in a number of different ways, the relationship was a complicated one and was never formalized. My interpretation is that UNTAET in fact did rely heavily on the CNRT for Timorese political participation. It proved such an attractive initial counterpart precisely because it was an umbrella Timorese organization that was explicitly not a political party; in other words, the fear of unduly influencing political outcomes led UNTAET to rely on the CNRT. In the longer run, however, this reliance on an umbrella organization masked the lack of consensus about what the institutional arrangements of the new country should look like.Footnote 56 It also had precisely the effect UNTAET feared, both by empowering FRETILIN leaders within the CNRT and by compounding the resistance-era, elitist nature of Timorese politics.

From the start, nevertheless, UNTAET attempted to avoid the politicization of the administration. Collaboration came initially through the newly created National Consultative Council, a small body with an East Timorese majority and a handful of senior UNTAET staff. In response to complaints about the delay in consulting the Timorese about political options for transition to self-governance, this morphed in July 2000 into the larger and entirely Timorese National Council, which comprised members of the CNRT as well as the Catholic Church and other civil society organizations. The National Council was intended to operate as a national legislature but it was appointed rather than elected, its members received little support in the way of financial or human resources, and Vieira de Mello retained absolute executive powers, including a veto.Footnote 57 At the same time, a coalition cabinet of transitional government was created, the East Timor Transitional Administration (ETTA). ETTA introduced Timorese proto-ministerial counterparts for the core UNTAET executive staff and the eight main cabinet posts were split – with four posts assigned to Timorese elites (Internal Administration, Infrastructure, Economic Affairs, and Social Affairs) and four to international staff (Police and Emergency Services, Political Affairs, Justice, and Finance).Footnote 58 Many believed that Gusmão himself chose the four Timorese cabinet members – two from FRETILIN, one from the more conservative Timorese Democratic Union (UDT), and one from the Catholic Church – reflecting UNTAET's reliance on CNRT in general and on Gusmão in particular, as well as the continued importance of Timorese political allegiances dating to 1975.Footnote 59 Together, the coalition government and the National Council were intended to provide “democratic institutions before democracy that could be the setting of democratic learning-by-doing at the national level.”Footnote 60

Yet these compromises on Timorization were too little and too late. By this time, Timorese elites were unsatisfied with even the National Council and ETTA co-governmental arrangements. The flawed relationship between UNTAET and ETTA was indicative of a fundamental transitional governance problem: the tension inherent in the UN's dual role as both government and transitional peace operation. ETTA, which was to assume the responsibility to deliver essential public services from UNTAET, was resource-starved in comparison. International cabinet members enjoyed a great deal of infrastructural support and much higher salaries, for example, than their East Timorese colleagues. Richard Caplan notes that the result of such inequities was “resentment and compromised effectiveness on the part of East Timorese administrators, who were already executing their responsibilities with serious handicaps.”Footnote 61 The UN's role as government compromised the institutional and human capacity-building necessary to construct an effective state infrastructure to take over at transition.

By 2001 Timorese elites had reached the consensus that the relationship with UNTAET was counterproductive and should be ended as soon as possible. In December 2000, the Timorese Cabinet members threatened to resign, using one of the few measures actually available to them in the absence of genuine political power, as Simon Chesterman observes, in “an attempt to challenge UNTAET's legitimacy by threatening its consultative mechanisms.”Footnote 62 They expressed their frustration in a letter to Vieira de Mello: “The East Timorese Cabinet ministers are caricatures of ministers in a government of a banana republic. They have no power, no duties, nor resources to function adequately.”Footnote 63 Xanana Gusmão expressed his and the CNRT's disappointments with UNTAET in his New Year address of December 31, 2000, echoing, in particular, the East Timorese leadership's irritation over their lack of political participation. In turn, the Timorese leadership's frustration over their exclusion from decision-making in the political arena meant that they fixated on political participation, rather than broadening their desire to govern into also calling for Timorization of the state apparatus and emphasizing capacity-building in that arena. Indeed, when offered the choice by UNTAET in mid-2000 between a “technocratic” solution that would accelerate Timorization of the state administration and a “political” solution to more quickly transfer political power to the Timorese, the country's leaders opted for the latter.Footnote 64 This had the effect, parallel to the dynamic in Cambodia, of failing to bolster the state as a countervailing center of governing authority.

While a process of Timorization was at least attempted at the national political level, the development of parallel community empowerment through political institutions at the district level faltered. International staff continued to dominate governance at the subnational level: even as late as March 2001, only 2 of the country's 13 District Administrators were Timorese. Caplan argues that one reason UNTAET was so hesitant to devolve authority to the subnational units was because of the lesson from the Kosovo experience, brought to East Timor by Vieira de Mello and some of his deputies, that it was essential to establish unchallenged authority over the entire territory. Yet the circumstances were different in East Timor, where the local leadership was at first entirely supportive of the UN's aims and the mission itself, and could have been entrusted with more authority much sooner. The other issue was that District Administrators were constrained in performing their jobs because of excessive centralization in Dili. UNTAET's head of the Office of District Administration, Jarat Chopra, resigned very publicly in March 2000 and a month later all 13 District Administrators signed a memo to protest the centralizing tendencies of UNTAET.Footnote 65 The one exception to the lack of Timorization within UNTAET was the Division of Health Services, which had a dual international–Timorese authority structure from the beginning and was very successful in delivering essential public services as a result. This cooperation was made possible by the existence of an organized cadre of Timorese health professionals along with senior UN health officials who understood and believed in the importance of working together with their domestic counterparts.Footnote 66

Other international organizations operating in East Timor had a very different position on Timorization and state capacity-building. Suhrke argues that the United Nations Development Program approach was based on the alternative assumptions that there were East Timorese with valuable administrative skills to be mobilized from the outset and that transition to an independent government would require the incorporation of Timorese into important positions.Footnote 67 The World Bank, in contrast to UNTAET, had early in the process attempted to conduct a skills inventory to identify those Timorese who could be brought into the transitional process.Footnote 68 It included East Timorese from the start in its November 1999 Joint Assessment Mission, rejecting UNTAET's view of a skills vacuum in East Timor.

UNTAET's slow moves toward the Timorization of government at the national level were matched by its reluctance to foster political participation at the subnational level, a pattern that was reinforced by the view of politics held among the Timorese elite. The story of the Community Empowerment and Local Governance Project (CEP) is telling in this respect.Footnote 69 The CEP was the first joint project between the World Bank and UNTAET as the sovereign government of East Timor. It was intended to support the creation of elected village and subdistrict councils so that block grants could be provided to the subdistricts, which would then decide on development priorities by adjudicating among village proposals. The project was designed to promote local-level participation in development and reconstruction decisions, and was intended in part to be an introduction to democratic and accountable governance. Many have observed that although the CEP was ambitious, it fit within the decentralized design of district administration that UNTAET and the World Bank had planned for East Timor. Yet UNTAET balked at the basic concept of the project proposed by the World Bank, arguing that local participation and formal recognition of local authorities by UNTAET could come only after formal elections. The CEP thus confirmed “the worst suspicions of the East Timorese: that the UN has no inclination to share power with them during the transition, or to include them in any decision-making beyond perfunctory consultation.”Footnote 70 UNTAET officials’ opposition to the CEP in early 2000 placed a severe strain on their relations with senior Timorese leaders, including Gusmão, and even with other international organizations and NGOs. The inter-agency rivalry over the project also revealed the different approaches to Timorization during the process, highlighting that there were other possible avenues toward increasing political and administrative participation that UNTAET simply did not take.

UNTAET was not the only organization to have trouble broadening political consultation. The CNRT itself was criticized by elements of Timorese civil society for failing to be inclusive, relying too much on past political currencies and traditional elites, and not paying enough attention to the current landscape of East Timorese politics and society. Timorese NGOs, for example, were dismayed at Gusmão's December 2000 suggestion that the CNRT would prepare a draft of the constitution that the elected Constituent Assembly would only need to “fine-tune” before its passageFootnote 71 – this was hardly the genuine participatory constitution-writing process that the UN had promised. Gusmão later favored the idea of deeper popular consultation but the idea of a national constitutional commission was rejected by the National Council.

The East Timorese Elections of 2001

As UNTAET moved slowly toward further Timorization, the CNRT umbrella was beginning to fracture in the face of differing elite viewpoints and objectives and FRETILIN re-emerged as the dominant party on the Timorese political scene. This core element of the CNRT was dominated by members of the East Timorese diaspora who had remained active in the resistance movement from afar – from Mozambique, in particular. They decided after returning to East Timor in 1999 that they would seek to be the party of government on their own and FRETILIN began the dissolution of the CNRT when it withdrew in August 2000. It thereby freed itself from the agreement among the parties that formed the umbrella organization not to set up branches below the district level and immediately began rebuilding its formidable organizational structure at the village level, a feat the other parties simply could not match. Gusmão spoke bitterly against this political mobilization and the fracturing of the identity of national unity underpinning the CNRT.Footnote 72

Political fragmentation increased as all the parties began to gear up for the Constituent Assembly elections of August 2001 – what one donor official called the “checkered flag” for political parties to start forming.Footnote 73 The guerrilla resistance leaders of FRETILIN's armed faction FALINTIL saw themselves as marginalized by the FRETILIN leaders who had returned from exile, whom the FALINTIL forces viewed as having sat out the long and arduous guerrilla battle in relative comfort. Gusmão remained unaffiliated with a political party, projecting an image of himself as above factional politics. A handful of small political parties formed: some appealed to labels and affiliations from the era of party formation in 1975, such as the Timorese Democratic Union; and others channeled newer voices on the Timorese political scene, such as the Democratic Party representing Timorese youth, many of whom had studied abroad and had become increasingly resentful of the old-guard politicians and their resistance-era governing plans.

FRETILIN was indisputably the most powerful and best-resourced party and it advocated early elections in the knowledge that it would triumph handsomely. It had governed East Timor briefly in 1975 and established a deep bond with the Timorese people over the course of the Indonesian occupation and the guerrilla insurgency it led. It had served as the organizational backbone behind the CNRT's ability to step into the institutional vacuum created by the attenuation of political and institutional development under Indonesian rule, during which no political, administrative, or professional class was allowed to emerge in East Timor. FRETILIN, however inaccurately, self-consciously took on the CNRT's mantle as a political umbrella organization. As East Timorese independence drew near, it shared some characteristics with other independence movements that morphed into political parties, such as India's Congress Party or South Africa's African National Congress. Perhaps most significantly, these umbrella political fronts tend to begin their elected political careers by attempting to mediate national sociopolitical cleavages internally rather than allowing them to play out in an electoral arena.

Reflecting their concern not to bestow undue legitimacy on any one party, many UNTAET officials feared that FRETILIN would win an overwhelming majority of the vote in the first elections and lead the country toward becoming a one-party state. They encouraged the Timorese to adopt a mixed voting system – combining first-past-the-post district representation and national party-list proportional representation – hoping that this would give smaller parties more representation.Footnote 74 FRETILIN nevertheless scored a large victory in the Constituent Assembly elections of August 2001, winning 55 of the available 88 seats. Although it won 57 percent of the overall vote, it secured 63 percent representation in the assembly by also winning 12 of the 13 district seats. The Constituent Assembly replaced the National Council; and a new Transitional Government, with a fully Timorized cabinet, was chosen. Although this cabinet was selected to present an image of national unity, FRETILIN's victory was reflected unambiguously in its hold over the most important and powerful cabinet positions.Footnote 75

Partnering with a small like-minded party, FRETILIN had the votes necessary to push through its draft constitution for approval with no need for compromise. It had been working on the task since first coming to government in 1975, while the other parties had not even begun to tackle the issue; furthermore, FRETILIN paid minimal attention to the results of the popular consultation conducted.Footnote 76 An Asia Foundation survey in 2004 reported that the Timorese citizenry was divided over whether genuine public participation had taken place: 44 percent responded that it did compared to 41 percent who felt that it did not. The FRETILIN-controlled proto-legislature thus defined the scope of its own powers, particularly vis-à-vis the other organs of government. Although numerous CNRT leaders favoured a pure presidential system for East Timor, the Maputo clique within FRETILIN that oversaw the design of the constitution explicitly subordinated the president to the government in a move that observers believe was intended to marginalize Gusmão on the political scene.Footnote 77 The final constitutional arrangements essentially neutralized the non-affiliated Gusmão's overwhelming mandate, over 82 percent of the vote, in winning the presidency in April 2002.Footnote 78 Ingram observes that, in effect, two rival centers of power were created – with the prime minister and government empowered to make policy, while the president retained enormous moral authority with the population – thus setting the scene for “fierce political contest over the following years.”Footnote 79 Finally, at the end of the transitional period, FRETILIN was also instrumental in transforming the Constituent Assembly into the National Parliament on independence, obviating the intended second election that other parties had anticipated would increase their own showing in the legislature.Footnote 80 The clique of returned FRETILIN diaspora leaders formed the core of East Timor's first Council of Ministers. It was not long before the political dominance of this group, with its uncompromising governance style and unilateral set of political priorities, was challenged as the new political landscape of East Timor evolved and matured.

Transitional Governance in Afghanistan

The transitional governance challenge in Afghanistan was very different from both the lack of consent involved in the peace settlement in Cambodia and the increasingly heated demands for local participation in East Timor. In Afghanistan, a dilemma shaped the political landscape and dominated the immediate peacebuilding challenge. On the one hand, governing the country required, as it had for centuries, the centralization of authority in Kabul. On the other hand, stabilizing the country in the aftermath of the civil war and the rout of the Taliban required the distribution of power to regional strongmen.

The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) became operational in early 2002 to support the implementation of the peace framework as laid out in the Bonn Agreement.Footnote 81 Over the first five years, an estimated $8 billion was spent on the peacebuilding operation in Afghanistan, with almost 30,000 military and civilian personnel deployed to assist the effort.Footnote 82 UNAMA was similar to UNTAC in that it was established to assist with a peace settlement, but it is telling that UNAMA was not designated a transitional authority by the Security Council; rather, it is a “special political mission” and is led by the UN's Department of Political Affairs, in contrast to the more traditional peacebuilding operations led by the UN's Department of Peacekeeping Operations.Footnote 83 The Security Council mandate did not explicitly endow UNAMA with any dimension of the Afghan government's sovereignty or executive authority, as it had the UNTAC and UNTAET mandates in Cambodia and East Timor, respectively. Furthermore, the United States was heavily involved in the Afghan political transition, particularly through its influential ambassador, Zalmay Khalilzad, who had Hamid Karzai's ear and served as one of his most trusted advisors.

UNAMA, however, was the focal point of the international community's assistance in the process of peacebuilding through transitional governance in Afghanistan. Indeed, although the Bonn framework envisioned the international community playing an “assistance” role, UNAMA in practice took on much more of a “partnership” role in governing with counterparts in the Afghan Interim and Transitional Administrations.Footnote 84 Entrusted with the bulk of donor reconstruction funds, instead of the interim government, UNAMA effectively operated for some time as a parallel administration, hence it qualifies as a transitional governance vehicle as defined in this book. It was responsible for many of the same state- and democracy-building activities as were the more formal transitional authorities (such as UNTAC and UNTAET), including particularly capacity-building and governing assistance for the Afghan Interim and Transitional Administrations. It also assisted the process by which the Transitional Administration was selected, followed by a constitution-drafting process and the holding of elections at the end of the transitional governance period.

UNAMA was explicitly intended to be a swing of the pendulum away from the broadly expanded scope of the two immediately preceding UN peacebuilding missions in Kosovo and East Timor.Footnote 85 Lakhdar Brahimi, the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Afghanistan, was extremely influential in determining the mechanics and substance of the Afghan political transition. Indeed, the design of UNAMA was based on the recommendations of a review of UN peacekeeping operations that came to be known as “the Brahimi report” after its chair.Footnote 86 Brahimi articulated the need for a “light footprint” in Afghanistan in terms of the UN and international presence in order to emphasize Afghan ownership of the process.Footnote 87 In practice, however, UNAMA was “arguably the most institutionally and normatively advanced integrated mission fielded by the United Nations in one of its most high-profile interventions.”Footnote 88 The international community, led by UNAMA, was intimately involved in both the transitional political process and day-to-day governance and state functions. In turn, it is evident that the Afghan Interim and Transitional Administrations, and later the elected government, derived their legitimacy from the UN-led transitional governance process originating in the Bonn Agreement and culminating in elections.

The Bonn Agreement provided a roadmap, complete with milestones, for a process of further negotiations among Afghans about political transformation and state reconstruction in their country. The Interim Administration and the UN adhered to the timetable stipulated in the Bonn Agreement to hold an Emergency Loya Jirga in June 2002, within six months of the peace settlement. The use of the grand council meeting, a centuries-old, traditional Pashtun consensus-building and conflict resolution mechanism, was considered an effective way to incorporate traditional forms of governance and thereby build domestic legitimacy into the political process. Loya jirgas had in the past made key governance decisions during periods of turmoil when no legitimate ruler was recognized by all Afghans, and the Northern Alliance agreed to a UN-monitored Emergency Loya Jirga as “the legitimating device for the process of building a more representative government.”Footnote 89 The key output of the forum was to decide on “a broad-based transitional administration, to lead Afghanistan until such time as a fully representative government can be elected through free and fair elections to be held no later than two years from the date of the convening of the Emergency Loya Jirga.”Footnote 90 In a general atmosphere of optimism about the future of their country, the assembled leaders reached agreement on the Afghan Transitional Administration (ATA) that would lead the country and its reconstruction.

The realities of constructing political order in post-conflict Afghanistan became more apparent, however, as the process of determining the composition of the ATA began to reflect the political challenges ahead. In effect, the Loya Jirga was hampered in fulfilling its mandate seriously because of the many unresolved power struggles going into the conference – and its outcomes perpetuated these conflicts rather than tackling them directly. According to the Bonn Agreement, the central objective of the Emergency Loya Jirga was to approve the key personnel who would govern the country as part of the ATA. Hamid Karzai was named the Transitional President, as expected. The composition of the rest of the ATA was not debated within the Loya Jirga forum, however. It was decided upon by key power-brokers after intensive behind-the-scenes negotiations over key portfolios, in a contentious debate that kept the delegates waiting in Kabul beyond the planned timeframe. The ATA slate was finally presented to the delegates as a fait accompli on the last day of the meeting, when Karzai announced the names of key cabinet members without providing a written slate or opportunity for discussion, let alone asking for a formal vote. There had been a widespread expectation among the delegates that the Loya Jirga would provide the chance to correct the factional and ethnic imbalances created at the Bonn conference.Footnote 91 But the composition of the cabinet remained much the same as in the Interim Administration, continuing to reflect the exigencies of informal power-sharing in an ethnically fragmented and centrifugal country: Tajiks retained the most powerful portfolios, including defense and foreign affairs, while Pashtun representation was increased slightly.

In short, many of the decisions made ostensibly by the Loya Jirga were reached behind the scenes in the interests of short-term stability and power considerations rather than for the longer-term purposes of strengthening the central state or boosting democratic participation and legitimacy and weakening traditional, unaccountable strongmen. Simon Chesterman observes: “Few people deluded themselves into thinking that the Loya Jirga was meaningful popular consultation – the aim was to encourage those who wielded power in Afghanistan to exercise it through politics rather than through the barrel of a gun.”Footnote 92 Critics of the Emergency Loya Jirga argued that it represented a missed opportunity to instill democratic practices in Afghan political culture, especially failing to assert civilian leadership and draw power away from the warlords.Footnote 93 Widespread reports surfaced immediately after the Loya Jirga of a series of backroom deals, outright intimidation, debate-stifling, and vote-packing on the floor that combined to prevent elected delegates from exercising their full authority and decision-making power as representatives of the people.Footnote 94 Many of the most notorious mujahideen leaders were treated with deference, sitting in the front row of the Loya Jirga and displaying full opportunistic behavior in exploiting the evolving political landscape to continue to suit their own ends. The most powerful were elevated into roles as vice presidents and provincial governors: Marshal Mohammed Qasim Fahim, who became leader of the Northern Alliance in September 2001 after Ahmed Shah Massoud was assassinated, served as Defense Minister and Vice President; Ismail Khan was made provincial governor of his stronghold of Herat; Haji Mohammed Mohaqeq, the former mujahideen leader of the Shia Hazaras became Minister of Planning; Gul Agha Shirzai, strongman in the south, was made governor of Kandahar. Karzai and his foreign backers thus demonstrated their intent to pursue a co-optation strategy that ignored past transgressions, a strategy that many human rights advocates criticized.

The tensions at the heart of constructing a workable political order in Afghanistan, so clearly on display in the outcomes of the Emergency Loya Jirga of 2002, continued to manifest themselves as UNAMA worked with the new ATA to implement a process of peacebuilding through transitional governance. Richard Ponzio describes how the international community struggled to reconcile divergent elements of authority in the country, observing that the need to incorporate traditionally legitimate sources of authority was often at odds with liberal democratization ideals.Footnote 95 At the heart of the peacebuilding challenge was “competing interpretations of what constitutes legitimate political authority.”Footnote 96 The clash of these distinct visions of political order is represented by Afghan warlords who, in continuing to assert their traditional forms of authority, have remained a serious obstacle to the consolidation of effective and legitimate government in Afghanistan. During the transitional governance period, large areas of the country remained dominated by private militias under the control of various anti-Taliban commanders, particularly those of the Northern Alliance. Many of the warlords and local strongmen assigned key posts in central and regional government resisted the demobilization of their personal forces and continued to enrich themselves with customs revenues and illegal financial flows. Karzai tried, from the Interim Administration period onward, to neutralize their independent power by incorporating them into his cabinet and provincial government structure, a strategy that worked with some (such as Ismail Khan and Mohammed Fahim) and less with others (such as Rashid Dostum and Gul Agha Shirzai).

Each of these strongmen pledged their allegiance to the government, but their willingness to submit to the authority of the central government was not truly tested during the transitional governance process.Footnote 97 These political realities met with mixed reactions from the Afghan people. Most understand that building post-conflict political order by co-opting some warlords was better than the instability that would be generated by excluding them – but these strongmen continued to be seen with blood on their hands. Ponzio's focus group of Afghan citizens revealed warlords and militia leaders to be among the least trusted groups in Afghan society, in contrast to tribal elders, who are viewed highly.Footnote 98 The political reality was simple, however: having accommodated and co-opted these regional power-holders into the new political order, it became increasingly difficult to diffuse the extent to which they were able to retain their political advantage and manipulate outcomes in their favor.

As with the other two cases, the transitional governance process in Afghanistan suffered from a mismatch between the realities of the domestic political scene and the international community's governance and statebuilding objectives. The milestones established by the Bonn process, as well as UNAMA's mandate and light footprint, meant that the international community was preoccupied mostly with the central government. This bias was exacerbated by the poor security situation outside Kabul, which hamstrung institution building activities, let alone any meaningful civic engagement, at the subnational level. The National Solidarity Program (NSP) is an exception that proves the rule: it was created by the ATA in 2003 as an integrated rural development and community empowerment program to improve development outcomes at the community level and thereby enhance the Afghan state's legitimacy across the country. Through the elected community development councils that are created to select and implement small-scale development projects, the NSP has proven perhaps the most successful way of building linkages between the government and Afghan society.Footnote 99 Ironically, it relies essentially on nongovernmental organizations for implementation.

The ATA faced its own problems in consolidating its authority outside Kabul. Alexander Thier points out both failures and relative successes on this front.Footnote 100 On the security side, the government remained a factional entity among other armed factions; it could not assert its monopoly over violence in the territory. On the executive front, by contrast, Karzai was quite successful, with the backing of UNAMA and the international community, at inserting into positions of authority in the ATA a group of technocrats who were few but relatively powerful. Ashraf Ghani, who became Afghanistan's president in 2014, was one of these key technocrats, serving as Karzai's Finance Minister in the ATA. One difficult yet effective strategy for demonstrating the authority of the central state as an alternative to traditional strongmen was an attempt to tie back to the center the cadres of provincial civil servants who were functioning in surviving subnational government bureaucracies and remained loyal to the concept of a central state.

Yet UNAMA's substantial international presence in Kabul and deep involvement with the business of the central government faded quickly outside the capital, as did the authority of the central government. During the transitional governance period, regional leaders continued to assert their own authority in the provinces, often with resources supplied to them by foreign patrons – aid agencies often carried out their own agendas in the provinces with little consultation with either central or provincial governments.Footnote 101 A World Bank survey team found in 2002–03 that subnational administrative structures were surprisingly robust and cautioned that the central government would have to act immediately to ensure that particular source of state strength was not quickly eroded.Footnote 102 Yet the ATA found it difficult to truly connect with the provinces – for example, it had trouble disbursing even meager funds and, in turn, subnational administrations received small budgetary allocations and remained extremely weak.Footnote 103

In short, while the political dimension of reconstruction was progressing along the Bonn milestones, state capacity-building was foundering in the absence of a robust, functioning Afghan administrative apparatus to guide reconstruction work.Footnote 104 On the statebuilding front, a telling dispute developed between the United Nations agencies coordinated through UNAMA on the one hand, and the Afghan Assistance Coordination Authority (AACA) – the government's coordinating representative to the donor community – on the other. The Interim Administration had created AACA by executive decree almost immediately after the Bonn Conference in order to orient international aid through a nationally owned program that prioritized direct assistance to the state. In parallel, the government wrote a National Development Framework (NDF) for the first donor conference to take place inside Afghanistan in April 2002, a comprehensive and integrated framework of development and reconstruction priorities. The NDF was widely viewed by donors as a strong statement of the government's vision as well as a structure to direct aid programming in the country. Yet many donors were skeptical that the government could effectively and cleanly execute direct budgetary support, with particular concerns being raised about the lack of functional administrative connection between the center and provinces. As a result, the international community continued to channel its financial assistance through the UN agencies and other external actors instead of directly to the government.Footnote 105 AACA officials, led by Ghani who oversaw the writing of the NDF, wanted a single channel of aid financing, through the government budget, and struggled against what they saw as the UN agencies’ attempts to undermine government ownership and streamlined statebuilding processes.Footnote 106

Responding to the increasingly contested transitional governance environment, UNAMA established an integrated coordination structure in mid-2002 to bring UN programs more in line with the government's capacity-building and reconstruction priorities. UN agencies were assigned to work as “secretariats” within ministries, providing personnel and technical assistance in support of the government's program, and UN programs became increasing embedded with those of the state.Footnote 107 For example, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) was the lead agency assigned to work with the Ministry of Finance and the Office of Administrative Affairs to manage the civil service payroll and establish new human resource management procedures; the UNDP then coordinated other donors’ work in this area. This more integrated system was beneficial in that it kept the Bonn process moving forward, especially facilitating the necessary dimension of international engagement in governance and capacity-building. The drawback, however, was that UNAMA became involved in internal debates over aid allocation authority and, as a result, coordination between UNAMA and the government was placed under constant strain. Alexander Costy observes that what became clear from such debates was that the UN had still not developed a strategy for incorporating greater national control over the management of aid resources as part of a peacebuilding operation.Footnote 108 This issue remained contentious in Afghanistan, resulting, after the transitional governance period, in the Afghanistan Compact, a renewed commitment to coordinated assistance under a government program negotiated between the Karzai administration and international donors in London in December 2006.

The Afghan Elections of 2004 and 2005