I Introduction

Cotton has a long history in Benin’s development strategies and it continues to play a majorFootnote 1 economic role today, accounting for about 50 per cent of export revenue (excluding re-exports) and 45 per cent of tax revenue (excluding customs revenue).Footnote 2 It contributes to the livelihoods of about one-third of the populationFootnote 3 and it constitutes 60 per cent of physical capital in Benin’s industrial sector (nineteen ginning factories, four textile factories, and two agro-food factories for vegetable oil extraction) where it generates about 3,500 paid jobs (Ministère de l’Agriculture de l’Elevage et de la Pêche, 2008). In addition, cotton contributes to activities in the services sector (e.g. transport and construction), and also plays a socio-politicalFootnote 4 role in rural development in Benin (see, e.g. Kpadé, Reference Kpadé2011).

Several indicators have been proposed to assess the economic performance of the cotton sectors in African countries (e.g. Tschirley et al., Reference Tschirley, Poulton and Labaste2009), but data limitation forces us to focus this analysis on three main indicators: production, yield, and acreage. In some cases, we discuss performance related to two additional indicators: the producer price of seed cotton; and Benin’s market share of cotton lint in the international market. We derive data on the first key three indicators from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT), allowing us to make a consistent comparative analysis with other countries over a long time period (1961–2017).Footnote 5 Data from three other sources (Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Economique, INSAE; Association Interprofessionnelle de Coton au Bénin, AIC; and Programme Regional de Production Intégrée du Coton en Afrique, PR/PICA) are used to discuss the performance of the sector over the recent period (2016–2018).

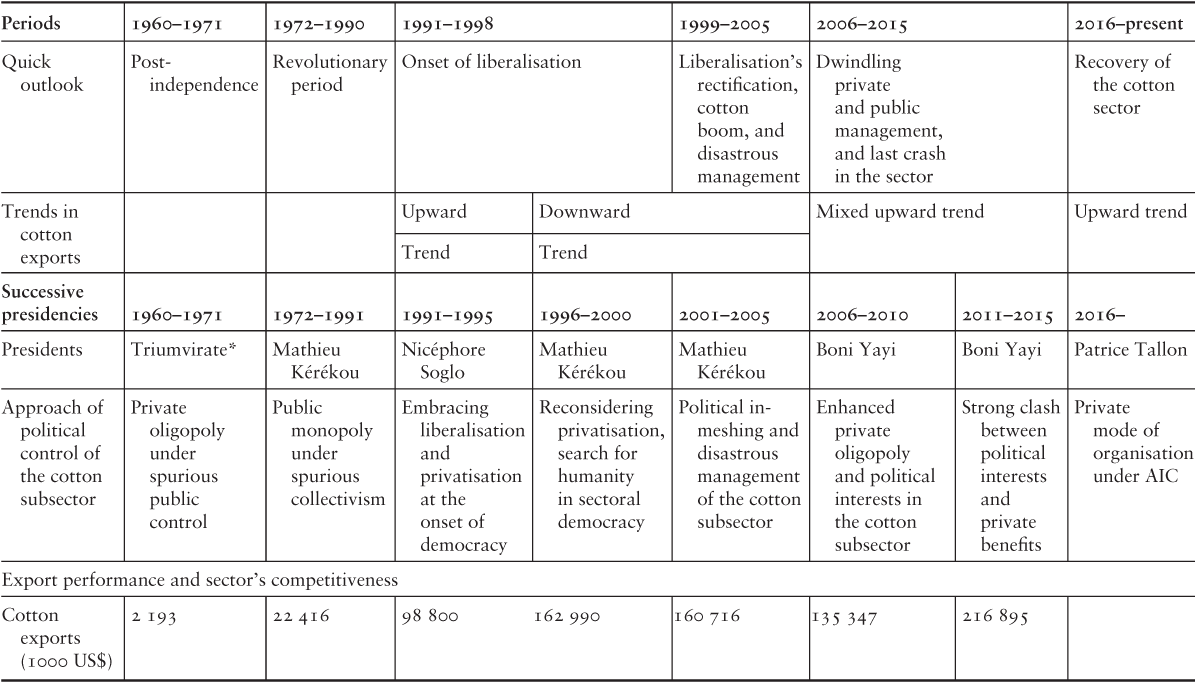

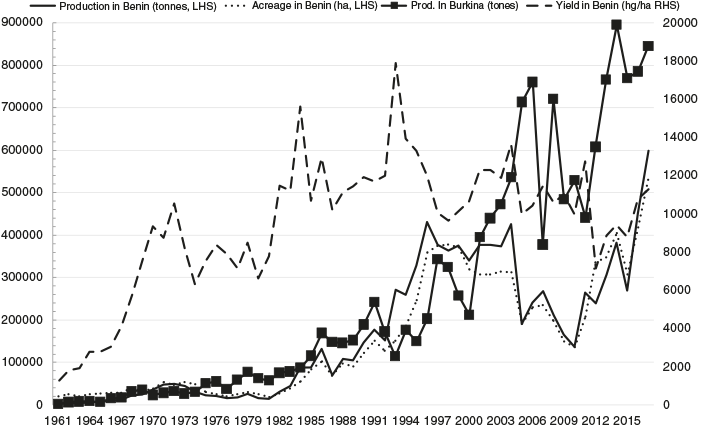

Figures 5.1a and 5.1b report the performance of the cotton sector in Benin and in Burkina Faso, a neighbouring francophone country; they give the production of seed cotton, yields, and cultivated area over the 1961–2017 period.Footnote 6 Figure 5.1a presents the performance in Benin and Burkina Faso in levels, whereas Figure 5.1b displays the performance of Benin relative to Burkina Faso (1961=100). The data in Figure 5.1b show a relatively poor performance in Benin’s production in 1962–1969, 1974–1992, and since the early 2000s. In 1961–1969, this was primarily caused by a more rapid expansion of acreage in Burkina Faso, since Benin was doing relatively well in terms of productivity per land unit. In the period 1974–1992, Benin lagged behind both in terms of yields and acreage.

Figure 5.1a Performance of the cotton sector in Benin and Burkina Faso

Figure 5.1b Performance of the cotton sector in Benin relative to Burkina Faso (1960=100)

In contrast, Benin outperformed Burkina Faso in 1970–1973 and 1993–1997. In the first subperiod, Benin’s performance was due to a spectacular improvement in yields, whereas in the second subperiod the result mostly stemmed from a more rapid extension in the area allocated to cotton. Figure 5.1a shows that, up until 1993 and except for the subperiod 1970–1973, the output of cotton in Benin moved roughly hand in hand with the cultivated land area, suggesting that improvement in yields did not play a significant role. In Benin, yields thus appear to be volatile and, more worryingly, in recent years they have come down to the level where they were in the early 1970s.

What are the causes of the performance in the cotton sector in Benin? This chapter aims to provide a diagnostic of the cotton sector in Benin. In particular, it reviews the underlying factors of the sector’s performance, with an emphasis on the role played by institutional factors. Over the years the sector has operated under different modes of organisation, between public and private types, each of which has been reversed over time. We aim to elaborate on the underlying causes of these changes and their implications for the performance of the sector. For this purpose, we make use of academic and grey literature. Moreover, we obtained information from key informants within the sector.

Section II introduces the framework of the analysis. Section III summarises the historical background. Section IV reviews the performance of the cotton sector in the period 1961–2016. It seems too early to provide an analysis of the sector after 2016, particularly because we lack crucial information on the current functioning of the AIC. We therefore do not provide an in-depth analysis on the performance of the recent period, but we leave such an analysis for future research. Section V presents the synthesis of the diagnostic.

II Analytical Framework

A Organisation of the Cotton Sector

There are nine main inter-related functions in the cotton sector:

1. Input supply and distribution.

2. Research (seed variety development).

3. Technical and extension services.

4. Production – seed cotton.

5. Primary marketing.

6. Processing – cotton lint, cotton seed, oil, etc.

7. Final marketing (of cotton lint, including export).

8. Quality control.

9. Price setting.

In this setting the performance of the sector depends on both domestic and external factors (e.g. Ahohounkpanzon and Allou, Reference Ahohounkpanzon and Allou2010; Baffes, Reference Baffes2004; Bourdet, Reference Bourdet2004; Cabinet Afrique Décision Optimale, 2010; Gergely, Reference Gergely2009; Kpadé, Reference Kpadé2011; Saizonou, Reference Saizonou2008; Yérima, Reference Yérima2005). We discuss the specific role of both of these sets of factors in what follows.

B External Factors

External factors include international forces that cause fluctuations in the global cotton price. Figure 5.2 displays monthly data on world cotton prices in US$ and CFA Francs (CFA), together with the CFA Franc/US$ nominal exchange rate over the period 1980–2017. The figure also displays the real producer price, which we obtain by dividing the nominal price by the consumer price index (CPI). The co-movement between the nominal and real price series is strong (0.65). Therefore, the rest of the discussion will be focused on the nominal series.

Figure 5.2 World cotton price and the CFA Franc/US$ exchange rate (1996=100)

The data show that variations in both the nominal exchange rateFootnote 7 and the US$ value of world cotton prices have caused great fluctuations in the CFA Franc value of the cotton price. In the second half of the 1980s, in 2001–2002, and in 2004–2009, for instance, the US$ value of cotton prices exhibits a declining trend, amplified by a persistent appreciation of the CFA Franc. We briefly discuss the causes of these fluctuations in the world US$ cotton prices. Thereafter, we elaborate on their impact on domestic cotton supply and the welfare of producers.

1 Understanding the Fluctuations in World Cotton Prices

Fluctuations in the world US$ price of cotton are caused by both demand and supply forces (see, e.g. Janzen et al., Reference Janzen, Smith and Carter2018). The impact of world supply operates through the action of subsidies in some leading cotton-producing countries, the USA in particular. For instance, FAO (2004) argues that world cotton prices would have been 10–15 percentage points higher in the absence of the subsidies to cotton producers in big producing countries. In value terms, the effect of subsidies amounts to a loss of about US$150 million in the export earnings of West African cotton-producing countries (Tschirley et al., Reference Tschirley, Poulton and Labaste2009). In 2003, a number of these African countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, and Mali) submitted a case to the World Trade Organization (WTO) to request the elimination of such subsidies by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and financial compensation. Following discussions at the WTO, the USA removed around 15 per cent of its subsidies to the cotton sector, but did not provide any direct compensation.

On the demand side, fluctuations in world cotton prices are explained by variations in global demand and by the development of substitutes in the form of synthetic fibres. The role of synthetic fibres in the global market has grown considerably over the past decades (see Baffes, Reference Baffes2004; Krifa and Stevens, Reference Krifa and Stevens2016). In particular, the share of cotton fibres in the world market of textile fibres shrank considerably from 70 per cent to below 30 per cent between 1960 and 2014, due to the marked decrease in the relative price of synthetic fibres (see Figure 5.3b below). For Benin and other West African countries, this new factor calls into question the sustainability of any long-term development strategy grounded primarily in the cotton sector. However, in absolute terms there is no decline in cotton fibre. We come back to this issue in Section V.

2 Welfare Impact of Cotton Price Fluctuation

Farmers are sensitive to the price of cotton, especially because cotton requires more labour effort and other inputs than other crops.Footnote 8 A number of studies find a positive response of the supply of seed cotton to production price and a positive effect of higher prices on producers’ welfare in Benin (e.g. Alia et al., Reference Alia, Floquet and Adjovi2017; Gergely, Reference Gergely2009; Hugon and Mayeyenda, Reference Hugon and Mayeyenda2003; Minot and Daniels, Reference Minot and Daniels2005; World Bank, 2004). For instance, Alia et al. (Reference Alia, Floquet and Adjovi2017) report price elasticities of the cotton supply ranging from 1.3 to 2.6.Footnote 9 In a related study, Minot and Daniels (2002) find that a 40 per cent reduction in the producer price of cotton results in a 6–8 per cent increase in rural poverty.Footnote 10 Moreover, they estimate the multiplier effect of cotton: national income would be reduced by US$2.96 for each US$1 decrease in the income of cotton farmers.

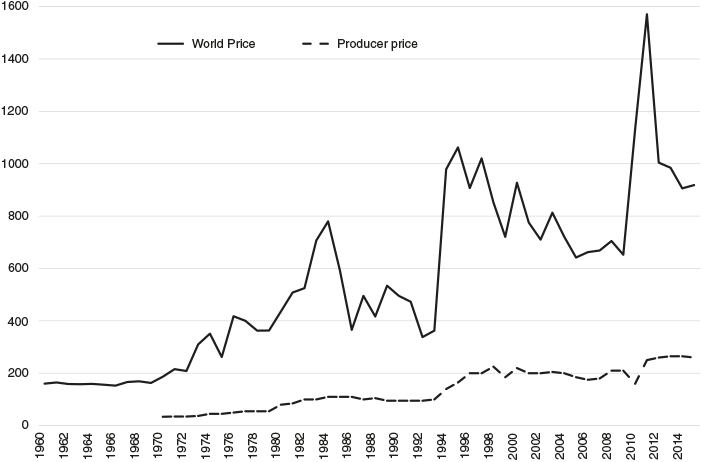

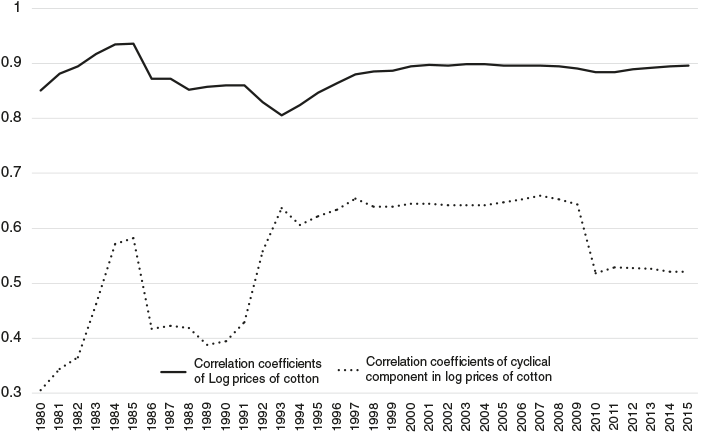

These micro-economic findings are in line with the aggregate data reported in Figures 5.3a and 5.3b. First, Figure 5.3a shows a strong co-movement between the world price and the producer price, although the strength of the correlation is less pronounced before 1992 when the statistics are based on the cyclical component of the two prices. We elaborate later, in Section III, the producer price-setting rules. Second, following the drop in cotton prices observed during the years 2001–2009, both the output and the surface of land planted in cotton have declined significantly in Benin and Burkina Faso. However, Benin displayed a much larger negative response, suggesting that country-specific factors may also explain the behaviour of cotton supply.Footnote 11 Conversely, cotton supply increased sharply in the same countries following a strong increase in the US$ price and the devaluation of the CFA Franc in 1994.

Figure 5.3a World and Benin producer prices of cotton (CFA/kg) and rolling correlation coefficients of the prices

Figure 5.3b World and producer prices of cotton (CFA/kg) and rolling correlation coefficients of the prices

C Domestic Factors

There are three main domestic factors affecting the performance of cotton: climatic risks, technical skills, and the quality of institutions. Climatic risks are exogenous and cannot be directly acted upon. Cotton supply depends on specific climatic conditions across the growing cycle: the length of the rainy season, dry spells, flooding periods, temperature, and solar radiation (e.g. Blanc et al., Reference Blanc, Quirion and Strobl2008). The role of climatic risks is not systematically discussed in this chapter. Technical skills depend on training and experience and will also not be discussed further here. But the role of institutions is of special interest to us. These include the type of coordination of the different functions in the supply chain and the specific rules and regulations that are involved.

There are two views regarding the required type of coordination in the cotton value chain: the French view and the World Bank view. The French view is based on the strategy developed by the Compagnie Française pour le Développement des Fibres Textiles (CFDT), a French parastatal company that modernised the cotton sector in the former French colonies of Africa. It advocates a vertical integration of the value chain through a single channel (a monopoly/monopsony) from farmers to ginnery companies and input suppliers. Moreover, the chain controls research activities for variety development, which are linked to extension services. In addition, it is in charge of promoting stable producer prices. After independence, the CFDT entered into joint ventures with African governments and the single channel was maintained. In the mid-1980s, when world cotton prices collapsed, subsidies from governments and money from donors were used to rescue the African cotton companies.

The World Bank view assumes that (state) monopoly is less efficient because of excessive public employment and political interference (e.g. Baffes, Reference Baffes2007). Such a monopoly can also be blamed for excessively taxing farmers who receive a rather small share of the world cotton price. Hence, allowing competition should decrease this tax and stimulate the supply of cotton. The view of the World Bank, also supported by the IMF, was dominant in the 1980s and was enforced through the structural adjustment programmes in many African countries in the 1980s and 1990s.

Conceptually, it is hard to say a priori which of the two modes of coordination would generate a better performance for the cotton sector, because each of the approaches has its advantages and disadvantages. For instance, while competition can boost producer prices, it typically implies higher coordination costs in a weak institutional environment characterised by imperfect credit markets, asymmetrical information, and weak contract enforcement. In a system where ginneries provide input credit to farmers, competition will encourage side-sellingFootnote 12 to cotton-buying competitors, discouraging credit supply by final buyers, thus causing inefficiencies in the input segment of the supply chain. By contrast, whereas a monopoly maintains a lower producer price, it will achieve a higher degree of coordination and better limit the side-selling problem. Hence, it is shown that the organisation of the value chain implies a trade-off between competition and coordination (e.g. Tschirley et al., Reference Tschirley, Poulton and Labaste2009). A recent empirical analysis by Delpeuch and Leblois (2014) confirms this trade-off. They find that African cotton producers in a competitive system achieve higher yields but lower acreage and production, whereas in a regulated system of the CFDT type lower yields but higher acreage and production are observed. On a related point, Baffes (Reference Baffes2007) argues that taxation of farmers has been reduced as a result of the liberalisation and privatisation of the cotton sector in Benin and many other African countries.Footnote 13, Footnote 14 Figure 5.3a also shows that the world price of cotton is much higher than the producer price, but we currently lack relevant and consistent information to discuss the underlying factors behind the difference.

Finally, there is also a debate about the mode of coordination among producers. For instance, should access to technical and agricultural services be organised at the individual or the farmer group level? Should production and input decisions be taken at the individual or the famer group level? Related to access to input and credit, a joint liability approach is used in the cotton sector of Benin and other West African countries. The joint liability approach may create, however, free-riding problems, which will generate inefficiencies in a weak contract enforcement environment. Farmers often report this free-riding problem in West African countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, and Mali), as evidenced by Thériault and Serra (Reference Thériault and Serra2014). Theoretically, it is difficult to predict the efficiency of the farmers who report the problem. For instance, inefficient farmers may report the problem more if they are afraid that their relatively low level of production will not make it enough to cover credit at reimbursement time. In this case, their assets may have to be seized in order to repay the loan. In the same way, efficient farmers may also report the free-riding problem because they have to pay for those who fail to repay their loans. Thériault and Serra (Reference Thériault and Serra2014) argue that producers who report more problems with the joint liability feature are more inefficient in a sample of West African countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, and Mali).

III Historical Background of Cotton in Benin: 1641–1960

A Pre-colonial Period to 1949: Private Mode of Organisation

The origin of cotton in Benin dates back to the pre-colonial period. Cotton was produced in the northern (Atacora–Donga and Alibori–Borgou departments) and central (Zou–Collines departments) regions of the country, and the raw cotton was entirely processed by the local artisanal textile sector (D’Almeida-Topor, Reference D’Almeida-Topor1995; Manning, Reference Manning1980, Reference Manning1982).Footnote 15 Map 5.1 shows that the Alibori–Borgou departments easily dominated cotton production. Moreover, the data reported in Figure 5.4 show that the central region, which was the second most important contributor to cotton production in the 1970s and 1980s, has declined considerably over time. In fact, the level of cotton production (not reported) has increased in the northern region, while it has decreased in the central region.

Map 5.1 Share of the main cotton-producing areas, 2016 (per cent)

Figure 5.4 Share of the main cotton-producing areas, 1979–2016 (per cent)

The northern region has a dry climate whereas the central region has a humid climate. A humid climate is less favourable to cotton production and this partly explains the decline in cotton production in the central region (e.g. Ton, Reference Ton2004). In particular, the producer cost of cotton is relatively high in that region, for example because farmers would need to consume relatively more pesticide to protect cotton from diseases. As a result, farmers switch more frequently to alternative crops when the relative producer price of cotton decreases (and/or the relative cost of cotton increases, or when the quality of input deteriorates). On the other hand, the support of development aid projects is one possible explanation for the increase in the production in the northern region.Footnote 16 We will elaborate on these points later (Figure 5.4).

During the colonial period (1894–1959), French entrepreneurs encouraged the production of cotton with the purpose of supplying cotton to their textile industries in France.Footnote 17 They developed two main strategies, which seem to be still relevant today (Kpadé and Boinon, Reference Kpadé and Boinon2011 and Manning, Reference Manning1982): (1) introduction of new varieties of the Barbadense family of cotton to improve productivity; and (2) promotion of small-sized farming (in order to limit labour movement).Footnote 18 In this context, ginneries were built in the central area (in Savalou and Bohicon) in order to process raw cotton.Footnote 19

The market structure of the cotton industry in this period was thus decentralised and potentially competitive, with the private sector in charge of the main activities, including marketing and processing. Following these efforts cotton production improved and exports to France began around 1904Footnote 20 (Manning, Reference Manning1982). The two ginneries were upgraded in 1924 (Savalou) and 1924 (Bohicon). However, the sector’s development was still marginal around 1926Footnote 21 (Figure 5.5). One problem was the low producer price compared to other crops (coffee, cacao) that were subsidised by the colonial authorities. Moreover, due to several market imperfections that characterise Africa’s rural areas, the market-based mode of coordination did not ensure efficient provision of inputs and agri-services to farmers (Kpadé and Boinon, Reference Kpadé and Boinon2011).

Figure 5.5 Cotton exports, 1903–1960 (tonnes)

B 1949–1960: Private Mode of Organisation but Regulated by the French Government

The modern development of the cotton industry came after the CFDTFootnote 22 was created in 1949 to take over the management of the cotton industry in the colonial territories. A research body, the Institut de Recherche du Coton et des Textiles Exotiques (IRCT), was established with the aim of developing higher yield varieties of seed cotton in support of CFDT activities. These changes occurred in the context of a new strategy initiated by France to develop its colonies after the Brazzaville conference. The strategy was based on development plans that were designed for each territory and financed by a French organisation, Fonds d’Investissement pour le Développement Économique et Social (FIDES). In Benin, FIDES financed two development plans in 1946–1952 and 1953–1960 (Manning, Reference Manning1982; Sotindjo, Reference Sotindjo2017).Footnote 23

In terms of organisation of the cotton industry, the CFDT promoted a single chain running from farming to exporting activities. In particular, the CFDT wielded monopsony power for the purchase of seed cotton from farmers and monopoly power for the supply of inputs, primary processing of seed cotton, and marketing of cotton lint. Typically, farmers would obtain inputs on credit before sowing, and they would pay this back in the form of seed cotton after production was realised. The CFDT also supported the acquisition of equipment by farmers and it provided them with technical and extension services. In addition, it encouraged the production of high-quality seed cotton by offering a price premium. The producer prices were set on a pan-territorial basis and announced before the sowing season. The CFDT bought the whole harvest from the producers at the announced price. In order to process the growing production, two new ginnery factories were built in 1955 in Borgou (Kandi) and in Atacora (Djougou).Footnote 24 Exports also improved, as can be seen from Figure 5.5.

IV Understanding the Performance of the Cotton Sector in Benin: 1961–2016

A 1961–1970: A Private Mode of Organisation but Regulated by the Newly Independent State

This period immediately following independence (in 1960) was characterised by political instability.Footnote 25 In line with the economic policy of the previous period, two development plans were implemented, covering the periods 1961–1965 and 1966–1970. These plans were largely financed by the French government through its development fund Fonds d’Aide à la Coopération (FAC), which replaced FIDES in 1959. The European Commission’s special fund for development, Fonds Européen de Développement (FED), also contributed to the financing of the development plans in Benin.

After independence, many rules and decisions were enacted to organise the agriculture sector.Footnote 26 As the political context was characterised by a growing nationalist movement that had started during the colonial period, the new government started to promote parastatal companies and national players in various activities of the economy. For instance, a registration card was introduced to regulate the primary marketing of seed cotton.Footnote 27 In the same way, there was a rule limiting exports of raw cotton, so that it could be processed inside the country.Footnote 28 A national stabilisation fund, the Fonds de Soutien des Produits à l’Exportation (FS),Footnote 29 was established in 1961 to protect agricultural exports when world prices became lower than the operating costs (producer price, processing costs, and transportation cost). FS was financed by export revenue and subsidies. Taxes were charged on all export products.Footnote 30

The IRCT introduced a new high-yielding variety of cotton (Hirsutum) to replace the existing one (Barbadense). This was done in the northern region in 1962 and later, in 1965, in the central region (World Bank, 1972, 1978). While the two varieties were still produced in the country, the government issued a provision (August 1965) to regulate their distribution. More specifically, the rule imposed that the two varieties should be commercialised separately and on different days in pre-defined local markets. In addition, two qualities of seed cotton were explicitly defined: high-quality cotton (1er choix), obtained from the current agricultural season and possessing attributes of homogeneity, whiteness, cleanness, and dryness; and low-quality cotton (2ème choix). Appointed controllers were charged with the task of identifying the quality of cotton offered for sale by any operator in the local market.

The price of high-quality seed cotton was determined on the basis of the processing price of cotton lint from the past year. A forecast was then made regarding the processing cost for the next cotton season, but the quality of these estimations was only indicative. As for the price of low-quality seed cotton, following a proposition by FS, it was fixed by the government at a given ratio to the price of the high-quality product. This price-setting rule was thus not based on any consideration related to the growers’ production costs. Each year, FS transferred this price information to the government for announcement to the public.

In the meantime, the Société d’Aide Technique et de Cooperation (SATEC) and the Bureau pour le Développement de la Production Agricole (BDPA – created in 1950), two other French parastatals,Footnote 31 were established in central Benin (in the Zou and Collines departments) and the north-western area (in the Atacora and Donga departments), respectively, to take over the extension and technical services and the marketing of seed cotton (Sotindjo, Reference Sotindjo2017; World Bank, 1969). If the CFDT concentrated on the north-eastern area (in the Alibori and Borgou departments) for the realisation of these activities, it continued to be the main organisation for the processing and exporting of all the cotton produced in Benin.

To expand its cotton sector, Benin received support from the FAC and the FED during the period 1963–1970. However, most of the funding was directly handled by the French agencies. The CFDT concentrated its efforts on the Borgou–Alibori department and SATEC concentrated on the central region. The project financed one government ginnery factory in Parakou in the Borgou department in 1968. Furthermore, the IRCT continued its research activities in relation to high-yielding varieties in the stations of Mono and Parakou. As a result, between 1961 and 1969, production and acreage increased from 2,482 tonnes and 20,608 ha to 23,959 tonnes and 31,884 ha, respectively.Footnote 32 Concurrently, yields increased from 1,204 hectogram per hectare (hg/ha) to 7,514 hg/ha over the same period.

Six cotton-processing factories, representing a total capacity of 60,000 tonnes, operated in Benin around the end of the 1960s (World Bank, 1972). This points to a serious problem of over-capacity, since total production in the country was about 24,000 tonnes of seed cotton in 1969. The CFDT owned four of these factories, two of which were located in the central region (Bohicon and Savalou) and two in the northern region (in Kandi and DjougouFootnote 33). The government owned the two remaining factories: one in the south-west (Mono) and the other in the north (Parakou). Through an agreement with the government, the CFDT managed the ginnery in Parakou, in addition to the four factories under its ownership. SONADER operated the second government ginnery in Mono. Formally, the agreement with the government stipulated that the CFDT was not allowed to purchase seed cotton from producers in the Mono region. However, it remained in charge of the export of all cotton lint processed in Benin, including the product processed by SONADER in the Mono region. In 1969, however, the responsibility for cotton exports was shifted from the CFDT to OCAD.

B 1971–1981: A Public Mode of Organisation Regulated by the Marxist–Leninist Government

The positive impulse of the 1960s continued its effect till 1972, when seed cotton reached a peak of 49,590 tonnes (Figure 5.1a). Thereafter, production started declining, from 1973, and reached a low level of 14,134 tonnes in 1981. We now detail a number of events that coincided with this poor performance of Benin’s cotton sector in 1973–1981.

While the French parastatals (CFDT, SATEC, IRCT) contributed significantly to the development of the cotton sector in 1963–1972, their mode of operation was criticised on a number of points (World Bank, 1970). For instance, the parastatals were blamed for their high operational costs, and for their single-crop development strategy, which ignored food crops and did not apply an integrated rural development approach in the areas of intervention. Moreover, the nationalist movement continued to grow, with the consequence that there was rising pressure to reduce foreign influence. In particular, the revolutionary government that took power in October 1972 promoted the ideas of ‘self-reliance’ and food self-sufficiency. Consequently, Beninese rural regional development agencies, known as the Centres d’Action Régional pour le Développement Rural (CARDERs), were promoted in the years 1969–1975, with a view to developing each department. This decision was taken in parallel to the creation in January 1971 of a national cotton agency, the Société Nationale Agricole pour le Coton (SONACO), charged with the development of the entire cotton sector in the country.

In order to further expand the cotton sector, however, foreign assistance was necessary because the country lacked technical skills and financial resources. In this context, a new project was implemented from 1972 onwards, jointly financed by the government (24.5 per cent), a grant from the FAC (27.5 per cent), and credit from the International Development Association (IDA) for the remaining 48 per cent. A primary objective of this project was to develop the activities of the newly created agency (SONACO), which was intended to progressively take over the management from the CFDT and SATEC of all activities in the cotton sector: technical and extension services, supply and distribution of inputs, processing, and marketing.Footnote 34

An important condition imposed on SONACO was that it should work in collaboration with the three French parastatals already operating in the cotton sector: SATEC, IRCT, and CFDT. In a first phase, it was expected that SONACO would concentrate on the management of the procurement of inputs and the agricultural fund. In addition, SONACO would contract with the CFDT and SATEC (the former for the north and the latter for the central region) to manage the project at the regional level (distribution of inputs, technical and extension services, transport, marketing). Moreover, through a joint venture with the government, the CFDT would manage all the cotton ginneries in the country. A similar joint venture between the CFDT and government cotton agency was successfully created in other francophone West African cotton-producing countries. Finally, it was expected that the IRCT would pursue its research and development activities in relation to higher-yielding seed varieties.

The project should have started in 1970, but serious institutional problems caused delays so that it was implemented only from January 1972.Footnote 35 In the beginning (1972), funds came from the FAC and the Government of Benin. As for IDA, it delayed its intervention until April 1973 because of institutional hurdles. In particular, SONACO unilaterally decided to take over direct control of the extension services in the field, in violation of the initial agreement to contract those activities to CFDT and SATEC. Furthermore, skills shortages and management problems at the top level of SONACO were a hindrance to the project’s smooth unfolding. Also, with a new government coming to power (on 26 October 1972) there came big changes in the staffing of the government agencies. All these unforeseen changes increased uncertainty; hence the decision by IDA to postpone the disbursement of its funds. In the end, IDA’s decision was proved to be the right one because the cotton sector performed very poorly from that time onwards (see Figure 5.1a).

There are many reasons for the collapse of the cotton sector. First, SONACO was unable to adequately develop field activities, especially input supply and distribution. In particular, procurement problems (problems with the licensing of suppliers and non-transparent competitive bidding) caused delays in the delivery of inputs to farmers. Moreover, inputs were left unprotected in the port of Cotonou and their quality deteriorated after they had been exposed to the rain. There were also problems in the delivery of ploughs. Furthermore, there were issues between producers and extension staff of SONACO, who were collectors of seed cotton at the village level. In particular, taking advantage of the illiteracy of the growers, some collectors tampered with the amount of cotton submitted by growers. All these problems were amplified when the CFDT and SATEC were forced to leave the country in 1974, when the regime adopted a Marxist–Leninist ideology and put more emphasis on food crops. This is where Benin differs fundamentally from other francophone West African countries. As a consequence of these problems, farmers turned away from cotton, especially in the central region of Zou–Collines, and they started to produce more maize for the Nigerian market, where demand noticeably increased following the first oil shock. This period marked the decline of cotton production in the central region that we highlighted earlier.

Changes in the other segments of the supply chain also compromised the performance of the sector. For instance, the fact that OCAD took over export activities from CFDT had the effect of reducing the quality of cotton lint exported by Benin. The Société de Commercialisation et Crédit Agricole du Dahomey (SOCAD) replaced OCAD in 1972, and it also took over management of the stabilisation fund FS. The change did not, however, improve the situation and the agencies continued to suffer from weak management problems. All these issues led the government and the donor to prematurely end the project around 1975.

There were, however, three main positive outcomes from the project, which also affected the sector later on. First, one additional government ginnery (with a capacity of 18,000 tonnes) was constructed in 1972 in the central region (Glazoué). Second, the research unit IRCT developed new high-yielding varieties (although in 1973–1980 their effects on cotton yield were nullified by the disruption of inputs and extension services): BJA SM 67 and 444–2–70. Third, and most fundamentally, village groups of farmers known as Groupements Villageois (GVs) were promoted in 1971 to take on some responsibilities in the cotton supply chain. GVs do not use collective asset ownership (land and equipment), and neither do they practise common production; instead, they merely coordinate within their group the distribution of inputs and the primary marketing of seed cotton. For inputs, a joint liability system known as caution solidaire was introduced whereby farmers in each GV are jointly responsible for input credit to be recovered at the time of the primary marketing of cotton. As regards primary marketing, village collection centres were created where each GV sells its seed cotton jointly to the collector. The project introduced this change in order to counter the tampering with the amount of seed cotton by some collectors. For this purpose, the project initiated a training programme to develop GVs’ skills in cotton weighing, as well as their literacy skills. GVs were paid for their involvement in the primary marketing, and revenue generated from that activity (ristournes) was invested in rural infrastructure, such as schools, wells, and health centres.

After having adopted a Marxist–Leninist ideology in 1974, in 1977 the government initiated two new types of farmers’ groups. One was the Groupement Révolutionnaire à Vocation Coopérative (GRVC), which is similar to the GV in terms of asset ownership and production organisation, but it produces food crops in addition to cotton. Moreover, GRVCs promote production en bloc of the members’ plots and a high degree of centralisation of extension services. Second, the government promoted collectivist cooperatives known as Coopératives Agricoles Expérimentales de Type Socialiste (CAETS) and Coopératives Agricoles de Type Socialiste (CATS).Footnote 36 Over time, however, CAETS and CATS did not succeed because they were not able to attract the most efficient producers (see, e.g. Yérima and Affo, Reference Yérima and Affo2009). Moreover, there were mismanagement problems.

The Marxist–Leninist government also introduced institutional changes in the other steps of the supply chain of cotton. In 1976 SONACO was replaced by a new parastatal, Société Nationale d’Agriculture (SONAGRI), and the responsibilities of the latter also included the management of inputs for food crops. In particular, SONAGRI was assigned the activities related to processing and input supply in the cotton chain. In contrast, extension services were from then on transferred to the development agencies, CARDERs. In the same period SOCAD was renamed Société Nationale pour la Commercialisation et l’Exportation du Bénin (SONACEB) in 1976 and a new stabilisation fund, the Fonds Autonome de Stabilisation et de Soutien des Prix des Produits Agricoles (FAS), was created in the same year. Following these additional changes, cotton production deteriorated further, from 30,654 tonnes in 1974 to a very low level of 14,134 tonnes in 1981. Moreover, the financial accounts of the government agencies (CARDERs, SONAGRI, and SONACEB) continued to be problematic.

Around the end of 1977, however, the government took a renewed interest in cotton and called upon the support of donors. As such, a technical assistance programme was implemented in 1977–1981 to prepare new development projects. The assistance programme was financed by IDA (50 per cent), FAC (31.25 per cent), and the government (18.75 per cent).

C 1981–1991: Public Mode of Organisation – Government Agencies Restructured and Reorganised

In 1981–1991 the cotton sector recovered strongly, as can be seen from Figure 5.1a: seed cotton increased almost eightfold over the period. This outcome was the result of four new projects that were developed by the government in collaboration with five donors (IDA, Banque Ouest-Africaine de Développement (BOAD), Caisse Centrale de Coopération Economique (CCCE),Footnote 37 the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)).

The projects strengthened the capacity of the cotton sector at both the national and regional levels. At the national level, they helped in restructuring and reorganising the existing government agencies in the cotton sector. As such, in 1983, FAS, SONACEB, and SONAGRI were replaced by a single new organisation, Société Nationale pour la Production Agricole (SONAPRA), which became responsible for the management of input supplyFootnote 38 as well as the final marketing of cotton. In addition to these institutional reforms, the government increased producer prices from around CFA Francs 80 in 1981 to CFA Francs 100 in 1982–1984, and to CFA Francs 110 in 1985–1986.Footnote 39

At the regional level the projects helped in strengthening the capacities of the CARDERs and the producer groups. In this respect, the first project concentrated on the Borgou region (1981–1988), the second targeted the Zou region, and the third focused on the Atacora region (1983–1988). Finally, the fourth project was a follow-up of the first project in the Borgou region (1988–1991). Hence, the most productive Borgou region received more support, which contributed further to the development of the region.

In 1981, the government transferred to the CARDERs all activities related to the transport and processing of cotton, although these functions were formerly under the responsibility of SONAGRI and should therefore have been passed on to SONAPRA. In addition, the CARDERs continued to manage extension services and the primary marketing of cotton, in collaboration with the GVs. Women’s groups were also promoted for the first time during this project. For extension services, a training and visit (TVFootnote 40) system was introduced in the fields. The projects supported the training of the CARDERs’ staff and the GV members, which facilitated input delivery and the provision of extension services to farmers. Moreover, the projects supported the acquisition of equipment by farmers and the construction of rural roads.

Following these institutional changes and the producer price incentive that was provided during the period, cotton production increased substantially from 14,134 to 88,098 tonnes in 1984, surpassing for the first time the ginnery capacity of 72,000 tonnes. From then, production further increased to 132,762 tonnes in 1986. In 1987, however, the sector experienced a crisis that caused production to regress to 70,203 tonnes. The crisis had to do with three main issues. First, Figure 5.2 shows a strong decrease in the US$ value of the world cotton price and a deep depreciation of the US$ in 1984–1986. As a result, the CFA Franc value of export revenue of the cotton sector depressed. Second, weak financial management by SONAPRA and the CARDERs combined with the continued support of the producer price value of CFA Franc 110 led to a depletion of resources of the stabilisation fund in 1985. In this context, the further decrease in world cotton prices that occurred in 1986 could no longer be absorbed by the stabilisation fund without external funding, because the government itself was also experiencing financial problems. The misallocation of the stabilisation fund included excessive pre-financing of the working capital of CARDERs, and transport and other logistics by SONAPRA to manage the excess production of cotton. Moreover, the debt of SONAPRA and the CARDERs with respect to the banking sector and external suppliers stood at about CFA Franc 7.6 billion. The cotton sector was therefore bankrupt in 1986.

In order to resolve this situation, a restructuring programme for the cotton sector was implemented in 1987–1991. The programme was executed by the government in collaboration with four donors (IDA, CFA, IFAD, and BOAD) within the framework of the second Borgou project, where money was provided to absorb the debt of SONAPRA and the CARDERs. An important condition imposed by the donors on the government in this restructuring programme was that external technical assistance should be mobilised to assist in the management of cotton agencies. The CFDT was thus called to provide technical and managerial assistance to SONAPRA and the CARDERs. The programme included three main reforms. First, the management of ginnery factories was transferred from the CARDERs to SONAPRA. As such, SONAPRA gained control of the main activities of the cotton sector and the CARDERs were left with the status of SONAPRA subcontractors, to manage field activities. From then on, the cotton sector became integrated around the monopoly SONAPRA, as was the case with the CFDT before 1972. A similar change occurred in other former francophone exporters of cotton, but Benin was different because unlike those countries the CFDT had no ownership share in SONAPRA. This was the case because the CFDT was forced by the Marxist–Leninist regime to leave the country in 1974.

Second, the stabilisation fund became the Fonds de Stabilisation et de Soutien des Prix des Produits Agricoles (FSS) and was passed on to an independent management committee. Moreover, the producer price-setting rule was reformed to include a price floor, which was announced by the government before the sowing season around April. The determination of the price floor was based on an opaque rule that took into account the financial viability of the whole cotton sector. If the export price exceeded the cost (producer price and other costs of the cotton sector) in a given year, the margin was distributed in the next year among producers, SONAPRA, the FSS, and the government, according to a pre-defined sharing rule. There were, however, some problems with the implementation of this new rule. In particular, the determination of the price floor was not transparent. Moreover, the price floor was not directly related to the world cotton price, such that the FSS was not always able to stabilise strong adverse price shocks. In any case, the government reduced the producer price from CFA Franc 110 to CFA Franc 100 in 1987 in order to contribute to the financial viability of the system. Moreover, input and seed distribution were limited to the high-yielding regions in 1987. As a consequence of these two measures, seed cotton production reduced considerably in 1987.

Third, various reforms were initiated to strengthen the administrative and financial procedures of SONAPRA and the CARDERs. For instance, internal audit units were established in these agencies in order to regularly check their financial viability. In the same way, administrative and accounting procedures were put in place to manage their invoicing systems. Furthermore, working capital was provided to SONAPRA and the CARDERs.

Following these reforms, the sector’s performance improved significantly. For instance, the reorganisation of the government agencies helped in reducing operating costs and the export marketing procedure (World Bank, 1995). Cotton production surged from 70,203 tonnes in 1987 to 177,123 tonnes in 1991.Footnote 41 In the same way, the GVs’ revenue increased from their participation in primary marketing, which they used to further finance local infrastructure. The promotion of women’s groups may also have increased their voice in matters related to rural development in the cotton-producing areas. One of the first careful micro-economic analyses of the ‘impact’ of these reforms in the Borgou region claims that women gained the most from these changes, because they were previously less involved in the cotton value chain (Brüntrup, Reference Brüntrup1997).

The sector realised this performance despite the fact that world cotton prices continued to decline over the period. However, it was not clear whether without the second Borgou project the sector would be able survive a similar crisis in the future. Hence discussions started between the government and the main donors to privatise and liberalise the cotton sector. The context was also characterised by a structural adjustment programme that began in 1989 and the political transition towards a democratic regime with the national conference in February 1990. A new constitution was adopted in the same year and a market economy was re-established. Hence, a new institutional framework for the agriculture sector was elaborated in the Lettre de déclaration de politique de développement rural (LDPDR) by the government in June 1991, after Soglo won the first presidential election in April 1991.Footnote 42 The LDPDR stipulated that the government should transfer the main functions of the supply chain to the private sector (primary and final marketing, supply and distribution of inputs, and processing).

D 1992–1999: Public Mode of Organisation under Liberalisation of Inputs and Ginnery Functions

Following the LDPDR, Benin began the liberalisation of the cotton sector in 1992 under the Soglo regime, which ruled the country till 3 April 1996. A gradual approach was taken. First, the input function was gradually liberalised in 1992–1995. Second, the private sector was licensed to operate in the processing component, starting from 1995. Third, the government initiated a broader agricultural restructuring project, the Projet de Restructuration des Services Agricoles (PRSA), in 1992–1999. PRSA aimed to promote a better quality of agricultural services by the private sector in the context of structural adjustment programmes that prescribed the reduction of government in various sectors of the economy. In the framework of PRSA many extension agents of the CARDERs were fired. In order to strengthen the capacity of the producers to take over new responsibilities in the sector, the Fédération des Producteurs du Bénin (FUPRO-Benin) was created in 1994 as the national professional trade union of the GV (Wennink et al., Reference Wennink, Meenink and Djihoun2013). The project was supported by seven donors: the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), FED, AFD, the German Technical Cooperation Agency (GTZ), IFAD, the United Nations Development Programme, and BOAD.

The liberalisation of the input component proceeded gradually from 20 per cent in 1992 to 100 per cent in 1995. In 1992–1994 SONAPRA was responsible for the residual shares of input supply. The details of the liberalisation were as follows:

1 In 1992 20 per cent of input supply and distribution was attributed to the private firm Société de Distribution Internationale (SDI), of which Talon was a major shareholder.

2 In 1993 the share of SDI increased to 40 per cent.

3 In 1994 60 per cent was attributed to the private sector, now to be shared among two firms:

• SDI obtained 50 per cent; and

• a new firm, Société Africaine de Management, d’Affrètement et de Commerce (SAMAAC), entered with 10 per cent, but it seems that it collaborated with SDI.

4 In 1995 100 per cent of input supply was transferred to the private sector, as follows:

• SDI (46 per cent), SAMAAC (15 per cent), Société des Industries Cotonnières du Bénin (SODICOT; 15 per cent); Société Générale pour l’Industrie et le Commerce (SOGICOM; 8 per cent); and Fruits et Textiles (FRUITEX) Industries (16 per cent).

The selection procedure of these firms for the input supply was done by SONAPRA according to its procurement system, which was limited to Beninese firms in the liberalisation process.Footnote 43 Why did the government not allow foreign firms to compete directly with domestic firms? There are suggestive indications that the procurement and licensing procedures were not totally transparent. For instance, in a recent open letter in 2018, the then president Soglo argued that he took the cotton activities from the CFDT and assigned the input supply activities to a group of ten entrepreneurs, including Benin’s current president Talon.Footnote 44 Moreover, in 1992, SDI received the inputs from SONAPRA directly and it only reimbursed SONAPRA for them afterwards (Yérima and Affo, Reference Yérima and Affo2009). It is also interesting to see that the number of firms increased greatly in 1995. We do not yet have a clear understanding of why this happened. However, 1995 was the year of the second parliamentary election in Benin and it is possible that the competition to win that election could be related to the one to enter the input market.

In addition to these reforms, the CFA Franc value of the world cotton price improved following the rise of the US$ value of the world cotton price and the CFA Franc’s 50 per cent devaluation in 1994 (Figure 5.2). Figure 5.2 shows that the producer price also increased over the period, but the gap between the two series became wider over the second half of the 1990s.Footnote 45 Following these changes, cotton production continued its increase further after 1991 and reached a high value of 430,398 tonnes in 1996. The improvement in cotton production was such that Benin outperformed Burkina Faso in 1993–1996, and there was an under-capacity ginnery problem in 1994.

Note, however, that this improvement in cotton production was primarily driven by land extension. In particular, while yields increased in 1993, they declined in 1994 and followed a declining trend till 1998. Several explanations can be provided for declining yields in that period. First, the result could be due to the price effect of imported inputs following the CFA Franc devaluation. As the price of inputs increased, producers were likely to reduce their input consumption and this could have potentially caused yield to decrease. Second, this outcome could relate to liberalisation having reached more farmers and hence the observed increase in land area. If the newcomer farmers were less efficient in cotton production or if they applied the cotton input for other crops, average cotton yields would have decreased. Third, the new private input suppliers could have been less efficient in managing and distributing inputs, causing delays in supply inputs or supplying a lower quality of inputs.

After President Kérékou took power on 4 April 1996, the number of private firms that obtained a licence to distribute inputs in the cotton sector further increased to eleven in 1996 and twelve in 1998. It is possible that this increase was related to the competition for the presidential election of 1996, in the sense that the Kérékou regime wanted to compensate some entrepreneurs for their support in winning that election. In the absence of clear evidence, this remains speculative, however. In any case, the quality of inputs deteriorated after the number of private firms increased in 1997–1998. Part of the explanation is that some of the newcomers were less efficient. We further elaborate on other institutional causes in what follows. We first discuss the liberalisation of the processing component.

In order to address the under-capacity problem of the processing factories, the Soglo regime initiated a liberalisation in 1995, when three new private ginnery factories of 25,000 tonnes capacity each obtained their licence to operate in Benin: ICB at Pehunco (Atacora), CCB in Kandi (Borgou), and SOCOBE in Bohicon (Zou). These three private factories are known as first-generation (of the liberalisation period) ginneries.Footnote 46 They were granted preferential treatments by the government in a number of areas. First, they obtained a preferential investment code regime (régime C), which grants 100 per cent tax exoneration on profit and an exoneration of duty on imported equipment and intermediate inputs for about seven years. Second, according to a regulation SONAPRA buys seed cotton from farmers and sells it to the private ginneries. This implies that SONAPRA supported part of the risk that should normally be taken by the producers and the private ginneries. Third, the amount of seed cotton to be allocated to the private firms should be proportional to their ginnery capacity and the total seed cotton production. Fourth, SONAPRA contributed 35 per cent to the capital of each of these three private ginneries. Applying this preferential treatment created problems in the future when the number of gin factories increased.

In 1997–1998, the Kérékou regime granted licences to the second generation of ginnery factories. Their total capacity ranged from 40,000 to 60,000 tonnes. These included three new factories for SONAPRA (one ginnery in Bohicon in the Zou department and two ginneries in ParakouFootnote 47 in the Borgou department) and five new private factories: Industrie Béninoise d’Egrenage et des Dérivés du Coton (IBECO) in Kétou (Patteau); Label Coton du Bénin (LCB) in Pouipnan (Zou); Société d’Egrenage Industriel de Coton du Bénin (SEICB) in Savalou (Collines), Marlan’s Cotton Industry (MCI) in Nikki; and SODICOT in Ndali (Borgou). This gives a total of eighteen gin factories, of which ten were owned by SONAPRA and the remaining eight were owned by the private sector. With these new gin factories in business, there was again over-capacity, with a total capacity of 442,500 tonnes compared to a production of 377,370 tonnes. In 1998 the gin capacity further increased to 587,500. The management of this over-capacity problem has been a major issue facing the Benin cotton sector.Footnote 48

Following these changes, production started on a declining trend from 1997 onwards. The decrease in 1996 and 1997 was not systematically related to the producer price, which did not decline. The producer price even increased from 1997 to 1998, despite the fact that the world price marginally decreased (Figures 5.2 and 5.3a, b). This implies that an alternative factor was responsible for the decrease in cotton production. A number of governance problems coincided with this poor performance. We first briefly discuss the change in producer prices and later elaborate on the factors behind the decline in cotton production. In April 1996 the FSS was replaced by the Office Nationale de Stabilization et de Soutien des Prix aux Producteurs (ONS) and a new price-setting rule came into effect. The new rule took into account the world price of cotton and also explicitly defined a margin for each of the main actors along the supply chain: producer; input supply and distribution, and ginnery factories.

As regards governance issues, the cotton sector experienced two conflicts in 1996–1997. The first conflict involved the government and the first generation of gin factories. In 1995 the private ginnery factories accumulated a lot of profit given the high production of cotton processed, but also because the CFA Franc devaluation implied a high value of the world cotton price in CFA Franc, but producer prices only marginally increased.Footnote 49 Given, however, that the firms were granted a preferential tax regime, an agreement was reached between the government and the firms that the latter would exceptionally contribute to government revenue in that year in the amount of CFA Franc 35 per kg of cotton processed. In compensation for this contribution, the agreement stated a decrease in the share of the government in the capital of those firms from 35 to 10 per cent. When the Kérékou regime came in 1996, the preferential tax treatment for these firms was reversed and the government wanted firms to continue to make the CFA Franc 35 per kg contribution. The firms contested this in the judicial court (as well as the Constitutional and Supreme Courts) and when they won the Kérékou government’s action was reversed.

The second conflict started in 1997 and related to issues between SONAPRA and the first private input providers (SDI and SAMAAC). The issues led SONAPRA to exclude these two companies from the input procurement in 1997. Following this decision SDI and SAMAAC brought the case to the judicial court (and the Supreme Court), where they won. In addition, SONAPRA had to pay fines to these firms, but an agreement was reached between the two parties. The agreement stipulated that SDI and SAMAAC would take 50 per cent of the input supply. This decision was applied from 1998 onwards and it contributed to further conflict, because the other suppliers were left with a lower amount of input to be supplied; they contested this rule. This situation led to increased problems in the input component: higher price of input, lower quality of input, and delays in the distribution of inputs (e.g. Bidaux and Soulé, Reference Bidaux and Soulé2005).

In order to resolve the problems, a number of actions were taken to privatise the management of the cotton sector. In 1998, for instance, the producer organisation FUPRO created the Coopérative d’Approvisionnement et de Gestion des Intrants Agricoles (CAGIA) for the management of input quotas between private firms, to which the government transferred the management of input supply and distribution in 1999. Other professional associations were created in 1999: the Association Professionnelle des Egraineurs du Bénin (APEB) for ginners, and AIC for the management of the whole supply chain.

E 2000–2007: Private Mode of Organisation by AIC

The important rules of privatisation were decided at a national workshop in May 2000, which saw the participation of the sector’s representatives. The seminar decided between two modes of private governance for cotton: (1) a unique private and vertically integrated mode of organisation at the country level; and (2) a private integrated mode of organisation at the regional level. Stakeholders decided in favour of the first mode. Moreover, a number of rules were put in place, such as fixed prices for inputs and cotton seeds across the whole country.

In June 2000 the government suspended the monopoly of SONAPRA on primary marketing, but the latter continued to manage its ten ginneries. Primary marketing was thus passed on to the Centrale de Sécurisation des Paiements et de Recouvrement (CSPR), which played a key institutional regulatory role in achieving the recovery of input loans to farmers and the payment of cotton seeds purchased by ginners. A development project funded by the World Bank, the Projet d’Appui à la Réforme de la Filière Coton (PARFC), was implemented in 2002–2007 by the inter-professional cotton association (AIC) to strengthen its capacity. One important change in this period was the fact that AIC started to manage the criticalFootnote 50 functions of the cotton’s sector, including technical and extension services that were previously under the responsibility of the CARDERs. It was also in this context where the CARDERs had to fire many workers as required by the PRSA. As a result, AIC had to recruit private extension agents, which had to join forces with the remaining CARDERs’ technical staff to do the extension work.

It is striking that this period of intense organisational change did not have any effect on cotton production. Moreover, conflicts emerged among the actors starting from 2002–2003. For instance, farmers complained about expensive input prices. In the same way, a number of private firms contested the outcomes of the input procurement procedure, whereas some ginneries found fault with the quotas of cotton seeds. As a result, they boycotted the AIC–CSPR–CAGIA system and started parallel activities. For instance, the dissident distributors attracted some farmers by proposing lower prices than those the official system was offering. However, the quality of the output delivered was not properly monitored. Likewise, the quality of privately supplied inputs could not be guaranteed and producers frequently complained that they were cheated in this regard. The ground was laid for a genuine crisis in the cotton sector. In particular, a lot of confusion was generated by the plurality of input sources and output outlets, and a number of farmers and ginners became severely indebted as the CSPR could no longer track their activities. The cotton sector in Benin thus experienced the side-selling problem discussed in Section II. As a consequence, the system encountered delays in payments, which discouraged farmers. Many of them turned away from cotton production, which was depressed in 2005. The GV also experienced conflicts. The joint liability performed poorly and farmers also complained about poor financial management by their leaders. Another issue experienced by the sector was poor extension services, because there were coordination problems between the private extension agents recruited by AIC and the ones that used to work in the CARDERs. The private agents also lacked technical skills. In fact, all the critical functions faced serious problems during that period.

The government’s reaction consisted of stepping in to finance the debt shortfall. Moreover, it introduced in 2006 institutional reforms to strengthen the professional associations. The producer organisation became the Conseil National des Producteurs de Coton (CNPC) and was limited to cotton producers, in contrast to the old FUPRO; the association of the input distributors became the Conseil National des Importateurs et Distributeurs d’Intrants Coton (CNIDIC); CAGIA was replaced by the Centrale d’Achat des Intrants Agricoles (CAI); and, finally, the organisation of gin factories was replaced by the Conseil National des Égreneurs (CNEC). Furthermore, the government adopted a framework agreement (accord-cadre) in 2006 with AIC, but with no significant effect on the sector’s performance.

In April 2007 the newly elected president (Boni Yayi) dissolved the agreement with AIC and an ad hoc Commission Nationale was established to manage cotton inputs. Moreover, the government allowed SONAPRA in that year to compete for input supply with private firms. This decision was surprising given that SONAPRA was already excluded from these activities.

F 2008–2012: Private Mode of Organisation and Privatisation of SONAPRA

In 2008, the industrial assets of SONAPRA were privatised and a new group, known as the Société de Développement du Coton (SODECO), was created to take over these assets after several problems in procurement management became manifest in 2006–2007. A first attempt to privatise the assets of SONAPRA failed in 2004–2005. The second also failed in 2007 due to problems involving a violation of the regularity procedure. SODECO was created as a joint venture between the government, accounting for a share of 66.5 per cent, and a private company led by Talon, accounting for the remaining share of 33.5 per cent.

In 2008 the government granted another licence for a new ginnery factory, SCN, in N’dali (Borgou), adding a capacity of 40,000 tonnes, despite the fact that the processing component was already experiencing an over-capacity problem. In 2009, a new framework agreement was signed between the government and AIC.

Overall, the domination by Talon’s group further increased in the sector because it merged with the majority of gin factories to create the ICA group. Consequently, the sector came under the control of a private monopoly. The government continued, however, to intervene in the sector. Moreover, the new organisational changes failed to improve the situation in Benin’s cotton sector. Yields and the cultivated area remained low.

G 2012–2016: Public Mode of Organisation Is Back

In April 2012 an international commission reported serious management problems by AIC. The problems included an over-estimation of the value of input supplied in the field, under-estimation of seed cotton submitted at gin factories, and mismanagement of government subsidies. Hence, the government cancelled the agreement signed in 2009 with AIC and a public mode of organisation took over its management. An inter-ministerial commission assumed the responsibilities of AIC, and SONAPRA and ONS were the main operational organisations. This new public management remained in place till April 2016, when President Boni Yayi finished his term. During this period the cotton sector continued to suffer, however. One positive change perhaps was a strategy introduced to check input consumption in the field. The national statistics institute went into the field with GPS to check accurately the size of land area of cotton in order to verify the input consumption requested. Several times discrepancies were found, and the additional money was recovered. This system continues to be implemented today.

H 2016–Present: Private Mode of Organisation Remains

In May 2016 President Talon re-established AIC after he was voted into office in April. An audit requested by the Talon government reported several mismanagement problems in the public governance of the cotton sector in 2012–2016. The new regime abolished around ten agricultural government agencies, including SONAPRA, ONS, and the CARDERs. Moreover, it initiated a broader reform agenda in the agricultural sector, where nine new regional development agencies were created. In addition, the government abolished subsidies to the cotton sector.

During the institutional survey developed for Chapter 3, the experts were not enthusiastic about these reforms.Footnote 51 Since 2016, however, seed cotton production has been increasing, according to data published by Benin’s GovernmentFootnote 52 (451,124 tonnes in 2016, 597,397 tonnes in 2017, 678,000 tonnes in 2018, 714,714 tonnes in 2019, and 728,000 tonnes in 2020). These figures suggest that the sector has been improving since 2016. The data presented in reports by PR/PICA also confirm this improvement in 2016–2018. The available information from AIC and INSAE indicates that the recent improvement can be explained by increases in both yields and acreage. Other this period (2016–2018) the producer price has not changed. As a result, this recent improvement in production, yields, and acreage could be related to changes in the organisation and the management of the sector by AIC and the government.

It is too early to further elaborate on the recent performance, as we currently lack systematic and consistent information in this regard; we therefore leave this analysis for future research. Gérald Estur, an expert who is familiar with the issues Africa’s cotton industry is facing, argued in May 2019 that this recent improvement in Benin’s cotton performance is related to changes in the management of the sector since the new government took power over the last three years. According to the expert, the changes have helped to restore trust among the stakeholders in the sector. The changes include a vertically integrated coordination approach by the government, timely payment of cotton growers, and efficient delivery of inputs.Footnote 53

V Concluding Remarks

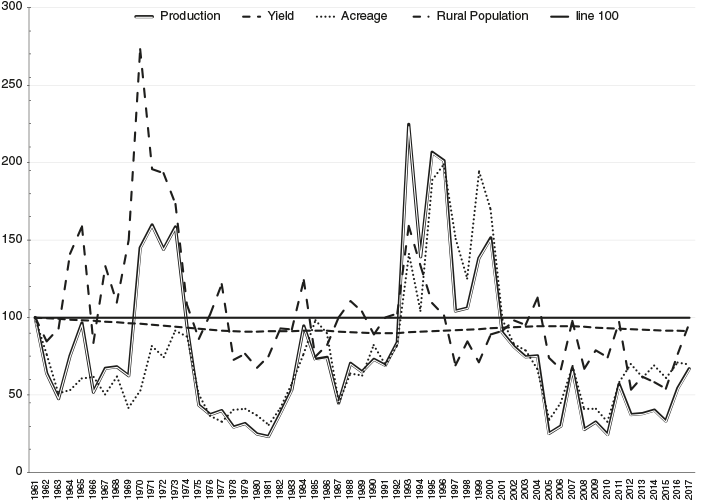

The cotton sector presents a unique opportunity to understand the causes and consequences of institutional changes in Benin over a long historical period. The sector has operated under different modes of organisation, oscillating between public and private monopolies over time, as summarised in Table 5.1. Initially, the cotton sector was managed by French entrepreneurs. From the end of the 1940s the sector came under the control of a French parastatal monopoly, the CFDT, which helped to modernise the sector with the support of development aid. In 1972, the Marxist–Leninist regime of Kérékou nationalised the CFDT, which was replaced by a number of government agencies. The system thus disintegrated, which increased coordination costs and resulted in poor performance. Thereafter, the sector entered a first restructuring period in the early 1980s and the government agencies were re-integrated into a single state agency, SONAPRA. Poor management problems and adverse world price shocks undermined the sector’s performance in 1986. After another restructuring plan the sector started a liberalisation period in 1992, after the country achieved a successful democratic transition in 1990. In particular, a liberalisation plan was implemented in 1992–1998 and private Beninese entrepreneurs started operating in the inputs and ginnery components of the sector. Thereafter, the sector experienced a crisis from the late 1990s and an inter-professional association of private entrepreneurs, AIC, became responsible for the management of the sector in 2000–2006, but the government continued to play an important role. In 2007 a new government suspended AIC. Thereafter, SONAPRA was privatised in 2008 and a dominant private group emerged. AIC became responsible again for the sector in 2009, but new problems in the sector led the government to suspend AIC from 2012 until 2016, when AIC was again given the management of the sector.

Table 5.1 Overview of mode of organisation of cotton across political regimes in Benin, 1960–present

| Periods | 1960–1971 | 1972–1990 | 1991–1998 | 1999–2005 | 2006–2015 | 2016–present | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quick outlook | Post-independence | Revolutionary period | Onset of liberalisation | Liberalisation’s rectification, cotton boom, and disastrous management | Dwindling private and public management, and last crash in the sector | Recovery of the cotton sector | ||

| Trends in cotton exports | Upward | Downward | Mixed upward trend | Upward trend | ||||

| Trend | Trend | |||||||

| Successive presidencies | 1960–1971 | 1972–1991 | 1991–1995 | 1996–2000 | 2001–2005 | 2006–2010 | 2011–2015 | 2016– |

| Presidents | Triumvirate* | Mathieu Kérékou | Nicéphore Soglo | Mathieu Kérékou | Mathieu Kérékou | Boni Yayi | Boni Yayi | Patrice Tallon |

| Approach of political control of the cotton subsector | Private oligopoly under spurious public control | Public monopoly under spurious collectivism | Embracing liberalisation and privatisation at the onset of democracy | Reconsidering privatisation, search for humanity in sectoral democracy | Political in-meshing and disastrous management of the cotton subsector | Enhanced private oligopoly and political interests in the cotton subsector | Strong clash between political interests and private benefits | Private mode of organisation under AIC |

| Export performance and sector’s competitiveness | ||||||||

| Cotton exports (1000 US$) | 2 193 | 22 416 | 98 800 162 990 | 160 716 | 135 347 | 216 895 | ||

* The triumvirate (Maga, Apithy, Ahomadégbé) was disturbed by many military coups d’états: Alley, Zinsou, Kouandété, etc.

What are the common causes of these institutional changes? What are the common institutional weaknesses in the cotton sector in Benin? What are their consequences for economic development in Benin? Can Benin develop a long-term development strategy based on cotton?

A Institutional Changes and Institutional Weaknesses: Causes and Consequences

There are a number of institutional weaknesses that can be derived from the foregoing analysis in the chapter: the discontinuity of regulations, reforms, policies, planned actions, or mandates of an organisation; the weak regulation of businesses (privatisation and liberalisation, licence management, financial management, accounting and auditing systems); weak capacity in public administration (including issues related to data management); vulnerability to world price shocks; excessive government and political interference; political appointments; overlapping responsibility; weak coordination; and imperfect credit markets, asymmetrical information, and weak contract enforcement. These weaknesses are potentially caused by rent-seeking; election and mass support; low technical and financial capacity; donors’ ideologies and their interests; poor management of conflict of interest; the ideology of political actors; colonisation and national anti-colonial revolution; culture; weak campaign financing; power concentration at the executive level; and distortions caused by subsidies in the dominant world cotton producers. We will now elaborate on a few of these institutional bottlenecks.

1 Discontinuity of Regulations, Reforms, Policies, Planned Actions, or Mandates of Cotton Organisations

This characterises a situation in which a government abruptly overturns existing regulations, reforms, policies, or planned actions by the previous government, or re-assigns the mandates of organisations in the cotton sector. This type of institutional weakness has been common over the whole historical period. In 1972, for instance, the military regime unexpectedly reversed the agreed decision between donors and the previous government that SONACO would contract with CFDT and SATEC to manage field activities (distribution of inputs, technical and extension services, transport, marketing). In the same way the governance of AIC was sharply interrupted several times by successive governments in the period 2006–2016. Furthermore, SONAPRA suddenly re-appeared in input supply and distribution in 2007 and 2012–2016, whereas a regulation already excluded it from participating in these activities in 1995.

Several factors may cause this type of institutional bottleneck: for instance, the Marxist–Leninist ideology of the revolutionary regime of the 1970s, the pronounced anti-colonial revolution at that time, and rent-seeking by supporters of the regime may explain why CFDT did not continue to play a dominant role in the cotton sector in Benin, but instead SONACO and other newly created government agencies suddenly took over the responsibilities. In the same way, rent-seeking, weak campaign financing, and electoral institutions, as well as the poor regulation of businesses, that characterise Benin may promote business–politics clientelist contracts, as elaborated in Chapter 4, and this could potentially explain the conflicts that emerged following the liberalisation and privatisation of the cotton sector in the 1990s. The dominant power of the new actors in the cotton sector, the excessive power of the executive, together with weak campaign financing and electoral institutions, could in turn explain the fluctuation between the public and private types of governance that we have witnessed since the 2000s.

This institutional weakness causes an increase in uncertainty in the cotton sector and increases the cost of agricultural services and the quality of input required by the farmers. As a result, it will discourage the production of cotton and/or induce low yields, which in turn will undermine the welfare of producers.

2 Weak Capacity in Public Administration, Colonisation, Donors’ Ideology and Their Interests

Donors, essentially France and the World Bank, have played a key role in the development of the cotton sector in Benin. The French colonisation and the interest of France in outsourcing its industries were the first explanatory causes of the development of the modern cotton industry in Benin. The French cotton institutions, such as the vertically integrated system of the value chain and the price stabilisation mechanism, initiated in the colonial period continue to persist today in Benin. Because the public administration of Benin has weak capacity, Benin requested the World Bank to join forces in developing the cotton sector further. The World Bank’s view of the organisation of the value chain is a bit different from that of France, in that it promotes a competitive-type system. The World Bank’s view has dominated in the institutional choices made for the management of Benin’s cotton sector, because the Marxist–Leninist government undermined the French interests in the 1970s given the anti-colonial sentiment that was observed at that time. Moreover, the pioneering role of Benin in its democratic transition and market economy in francophone Africa further contributed to making Benin different in the liberalisation and privatisation process in the cotton sector in West Africa.