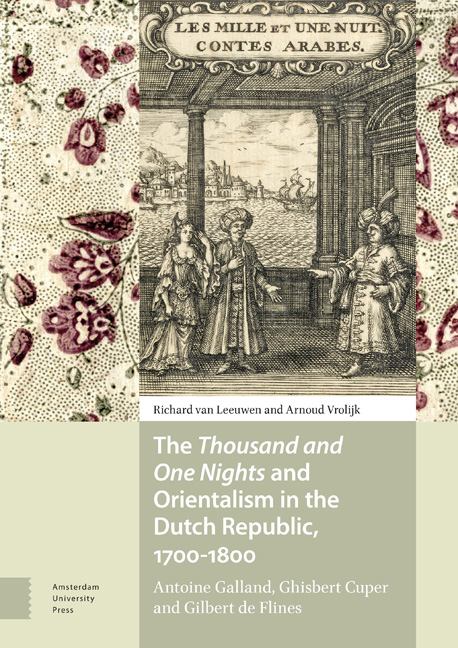

Thousand and One Nights and Orientalism in the Dutch Republic, 1700–1800

Thousand and One Nights and Orientalism in the Dutch Republic, 1700–1800 Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 The Thousand and one nights and literary Orientalism in Europe

- 2 Dutch Orientalism before 1700

- 3 Antoine Galland and Ghisbert Cuper

- 4 The early editions of the Nights

- 5 Gilbert de Flines

- 6 Later editions in the eighteenth century

- 7 Dutch Orientalism in the eighteenth century

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 Bibliographic survey of Dutch editions, 1705-1807

- Appendix 2 The David Coster engravings

- Appendix 3 Text samples of the Dutch Nights

- Appendix 4 French and Dutch quotations

- Illustration credits

- Bibliography

- Index

2 - Dutch Orientalism before 1700

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 The Thousand and one nights and literary Orientalism in Europe

- 2 Dutch Orientalism before 1700

- 3 Antoine Galland and Ghisbert Cuper

- 4 The early editions of the Nights

- 5 Gilbert de Flines

- 6 Later editions in the eighteenth century

- 7 Dutch Orientalism in the eighteenth century

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 Bibliographic survey of Dutch editions, 1705-1807

- Appendix 2 The David Coster engravings

- Appendix 3 Text samples of the Dutch Nights

- Appendix 4 French and Dutch quotations

- Illustration credits

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Although he found some difficulty in obtaining a scholarly position, later in life Antoine Galland established himself as a well-respected academic in his position as professor of Arabic at the Collège Royal and as a numismatist. He regarded his translation of the Nights as a leisure activity and had mixed feelings about the fact that the French aristocratic public was much more impressed by his fairytales than by his learned tomes on antique coins and inscriptions. In the Dutch Republic, too, the history of Orientalism as a cultural phenomenon is closely linked to the development of academic institutions. In the seventeenth century universities had a well-defined role in Dutch society. The sons of respectable families followed a core curriculum mainly based on Classical literature and philosophy, followed by a training for a career in one of the free professions: the Protestant ministry, medicine or the law. Teaching, tuition and publishing were exclusively in Latin. Modern languages did not come into the equation until the very end of the eighteenth century, when chairs were founded for Dutch; chairs for French and English would follow suit only in the nineteenth century.

In Oriental studies slightly different rules applied. From the sixteenth century onwards, Hebrew was taught almost exclusively in connection with theology, but Arabic held its own as part of the humanist canon until the dawn of the eighteenth century. During the seventeenth century the University of Leiden played a leading role in the field of Arabic and Oriental studies in the Dutch Republic. In 1613 a chair in Arabic studies was established at Leiden, the fourth in Europe after Catholic Rome and Paris and Protestant Heidelberg. The first incumbent was Thomas Erpenius (1584-1624), who acquired fame particularly for his Arabic grammar (1613), which became the standard work in Europe for learning and studying Arabic and which remained in print until well into the nineteenth century. His pupil and successor Jacobus Golius (1596-1667) not only edited Arabic texts and published an Arabic dictionary (1653) but also acquired more than two hundred Arabic manuscripts for the library of Leiden University. In addition, he assembled a private collection of equal size which is now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. In 1638 the German student Levinus Warner (c.1618-1665) arrived in Leiden to study Oriental languages under Golius.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Thousand and One Nights and Orientalism in the Dutch Republic, 1700–1800Antoine Galland, Ghisbert Cuper and Gilbert de Flines, pp. 29 - 44Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019