In April 1819, the writer Hester Lynch Piozzi (1740–1821) penned a letter to a friend encouraging him to acquire a copy of a newly published exploration narrative. She enthused: ‘But you should really get Ross’s Narrative of the Arctic Expedition. One view of the Crimson Cliffs and new-discovered natives in the fine Plates annexed to that Volume; give you far better and more distinct Notions of what they saw than any words which can be put together.’1 Piozzi was referring to the fold-out colour plates in John Ross’s Voyage of Discovery (1819), one of the first nineteenth-century narratives of Arctic exploration. Her recognition of the superior power of the visual to convey the appearance of little-known environments lends weight to the importance of interrogating illustrations as essential components of text, acknowledging the great influence they held over the nineteenth-century eye. In Piozzi’s words, ‘what they saw’ reveals the power of such narratives, particularly in their illustrations, to be regarded as eyewitness accounts. It also reflects the wide audience for Arctic exploration literature, as attractive to an elderly woman as it was to a naval captain.

Only ten such narratives were to be published in the first half of the nineteenth century, but the intensity of the search for Franklin saw an explosion in Arctic accounts; between 1850 and 1860, at least twenty-four Arctic exploration and travel narratives were published in book form by members of Franklin search expeditions.2 This represented a sudden increase in books about Arctic travel, fuelled by the large number of expeditions (thirty-six) that took part in the search and the public interest in Franklin’s mysterious disappearance. This chapter deals with the representation of the Arctic in these books, specifically with those produced by maritime (as opposed to overland) voyages, and with the mediation of both pictures and texts through their publication. The majority of these Arctic narratives are illustrated, ranging from a single tinted frontispiece in Robert Goodsir’s An Arctic Voyage to Baffin’s Bay (1850) to over three hundred monochrome prints in Elisha Kent Kane’s Arctic Explorations (1856). The importance of the ‘dialogue between word and image’ in illustrated books requires the use of both ‘visual and verbal interpretation, in order to show how the interaction between pictures and words produces meanings’.3 The ‘visualising’ of the Arctic, in both senses – through actual printed plates and through descriptions in words that invoke images, or phantasmata, in the mind of the reader – is of key importance here, demonstrating how a very visual Arctic was created for readers. The representation of the Arctic was heavily dependent on factors such as the success and duration of the voyage, the way in which an author wished to portray himself,4 and the visual culture of the nineteenth century.

The authors and illustrators of narratives drew on popular visual culture to aid their representation of the Arctic. The influences of panoramas, paintings, exhibitions such as tableaux, and magic-lantern shows can be discerned in the choice of language and illustration. As well as this, the technique of virtual witnessing, Romantic poetry, and referencing experiential memories all served to make the Arctic more visible for readers. The illustrations themselves can often be seen to display a triadic canon of motifs that became associated with Arctic exploration, ensuring that the main themes of the story are evident by merely glancing at the illustrations: masculinity signified by hunting; peril signified by the ship trapped in the ice; and exploration signified by new horizons and headlands.

First-time visitors to the Arctic, particularly those on ill-prepared expeditions, employed aesthetic language to describe the environment they encountered. The ‘man versus nature’ trope, so often used in the narratives of polar exploration, appears with regularity throughout texts. Integral to this was the setting of the narrative and the stark geology and ice of the Arctic that can be seen to resent or ‘frown’ upon the intruders who dared to approach its ‘dread shores’.5 By contrast, the narratives of repeat visitors to the Arctic, and those who spent consecutive winters there successfully, show a decrease in their use of aesthetic language as they become embedded in the environment as a local place, in practical terms or in its emotional resonance acquired through memory. This was particularly facilitated by the act of wintering over, a method of securing a home in the ice that was possible on ship-based maritime expeditions. In this way, some narrators of the Franklin search expeditions differ in their mode of looking from British explorers described by Mary Louise Pratt, who search for the source of the Nile with the ‘monarch-of-all-I-survey’6 mode of looking. For these long-term visitors to the Arctic, the environment was viewed in more practical, less aesthetic terms and the surrounds of winter quarters became their locality, causing them to lean towards behaving more like ‘inhabitants’ for whom the same spaces are ‘lived as intensely humanized, saturated with local history and meaning’.7 Indeed, the establishment of winter quarters enabled the creation of places, or ‘spaces people are attached to in one way or another … a meaningful location’.8 Yi-Fu Tuan equates space with movement and place with pauses,9 reminding us that the immobility of the Arctic search ship in winter is distinct from the ship that moves through the environment.

However, the printed visual depictions in such narratives often jar with the verbal picture, showing only the Arctic in winter and failing to display the unthreatening greenery and foliage of the Arctic summer that is described in the text. Such representations display the influence of the publisher’s commercial interests and the hand of the metropolitan artist. This mirrors visual representation of the region today where an over-emphasis on winter has led to the general perception of the Arctic as a frozen icescape; twenty-first-century narratives, such as that surrounding the Greenland ice-core drillings, reproduce the Arctic as an ‘empty, frozen space, waiting to be conquered by scientists’.10 This attitude continues to configure the Arctic as the testing ground for white masculinity, an image that is not compatible with flora and greenery. In contrast, the Inuit climate change, cultural, and human rights advocate Sheila Watt-Cloutier references the ‘preconceived notions of the Arctic and Inuit that many people hold’ when she tells us as clearly as possible: ‘The Arctic is not a frozen wasteland.’11

Although critics such as Jen Hill have pointed out that in the nineteenth-century popular imagination the Arctic was empty,12 narratives written by members of search expeditions can be full of Indigenous presences when they wintered near local settlements. Furthermore, the ways in which Inuit, Chukchi, and Iñupiat were represented in the narratives by those who had long-term contact with them suggest that certain individuals and groups were held in higher regard than the lowest rank on board ship, that of the seaman. After all, expeditions used them for navigation, clothing production, hunting, and social interaction, often benefiting from an astounding level of hospitality and goodwill on the part of Indigenous families. However, it can be said of both seamen and Indigenous Arctic peoples that the attitudes of the higher-ranking British expedition members towards them were paternalistic, perhaps in many ways similar to the approach of Danish colonialism in Greenland, which Nanna Katrine Lüders Kaalund identifies in the narrative of Carl Petersen, whose ‘approach to asserting his superiority to the Inuit’ was ‘shrouded in paternalistic rhetoric’.13

Between 1850 and 1852, seven travel narratives by members of Franklin search expeditions were published. In 1853, a further five Arctic travel narratives of the search appeared in print. Unlike the Arctic exploration narratives from 1818 to 1848, which were (largely) published by John Murray and controlled by John Barrow (First Secretary to the Admiralty),14 the narratives of the mid-nineteenth century were made available by a wide range of companies, including the firm of Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, which published four Arctic narratives between 1851 and 1852. The cost of narratives varied dramatically during the period, from one shilling and sixpence for a small single volume to thirty-six shillings for a heavily illustrated two-volume narrative.15 As Adriana Craciun points out, the death of John Murray II in 1843 and of John Barrow in 1848 ended the ‘polar print nexus’ and ‘made possible the explosion in popular Victorian writings on the Arctic’.16 Of course, this new explosion in writing was also made possible by the large number of expeditions participating in the search for Franklin.

This chapter looks at the representation of the Arctic in a broad range of maritime narratives from the search expeditions, including those of Robert Goodsir, William Parker Snow, and Edward Augustus Inglefield, who are all distinguished by writing narratives of summer voyages. In contrast, I also look at the narratives of those who spent winter in the Arctic, like Sherard Osborn. Given the prominence of Osborn in the history of exploration literature of the Arctic, not least as the editor of two on-board periodicals, I pay a significant amount of attention to his published narrative.17 Furthermore, repeat visitors like Francis Leopold McClintock, who voyaged to the Arctic four times before (reluctantly) publishing a narrative, and George Frederick McDougall, who wrote a narrative of his second expedition to the Arctic, are important in showing how the Arctic became familiar. Another type of representation is evident in that of the long-term visitor like William Hulme Hooper, who spent several consecutive winters in the Arctic. The narratives of Isaac Israel Hayes and Elisha Kent Kane, who were on the ill-equipped Grinnell expeditions, represent the disastrous voyages for which the Arctic has become renowned.

Techniques of Making the Arctic Visible

From the late eighteenth century to the 1850s, ‘geographical exploration and travel tales captivated public audiences and journalistic commentators alike. Everywhere, it seemed, was coming under the explorer’s gaze.’18 Explorers’ accounts often achieved bestseller status, providing excitement for readers with the authenticity of a real adventure.19 Texts like Constantine Phipps’s A Voyage towards the North Pole (1774) and Samuel Hearne’s Journey … to the Northern Ocean (1795) provided later authors of both literary and exploration narratives with models on which to construct their Arctic imagery. Early nineteenth-century Arctic exploration, which had resulted in numerous publications and exhibitions, meant that the Arctic was firmly established in the public imagination when Franklin set out on his final voyage in 1845.20 Narratives dealing with Arctic exploration, like William Edward Parry’s Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage (1821) and Ross’s Voyage of Discovery (1819), were presumably well read on board the search vessels. We are fortunate in having access to a library catalogue21 that was printed aboard the Assistance during the Belcher expedition of 1852 to 1854. This records at least sixty travel and exploration narratives in the collection, including Parry’s and Franklin’s from the 1820s, Edward Belcher’s Pacific narratives, and Two Years before the Mast (1840), a memoir describing life as a common seaman by the American Richard Henry Dana, which had been published in Britain in 1845.22 This presence of travel and exploration narratives, representing at least 9 percent of the library’s total,23 meant that expedition members were well aware of the genre and attuned to the publication potential of their own experience. Books on geography, history, travel, and biography made up 40 percent of the library’s collection.

Through their use of language and illustrations, the authors and illustrators of narratives drew on popular visual culture (particularly the nineteenth-century culture of exhibition) and memory (both personal and collective) to render the Arctic visible for readers. Visual media also strongly affected the way in which a first-time expedition member, like William Parker Snow, witnessed the Arctic. With illustrations, poems, and vivid verbal descriptions all leading towards creating a visual Arctic for the reader, the technique of ‘virtual witnessing’ was also incorporated into the narrative, whereby authors generated naturalistic images in the minds of readers through the use of language and by their choice of illustrations.24 These visualisations help to form memories and phantasmata, or images in the mind.25

In Osborn’s Stray Leaves, the third plate, Winter Quarters, is placed beside the corresponding text on the facing page.26 The illustration is peaceful, with the four ships represented against a lightening sky and bright icescape. The horizontal lines of the ice and the topography create a calm atmosphere and our eye is drawn to all the interesting details in the lower third of the picture, under an immense Arctic dawn. The scene connects with Osborn’s invitation to the reader to enter into his virtual panorama, reminiscent of the experience of viewing a panorama in London. Initially, Osborn described the environment as the expedition members experienced it: ‘a full, silvery moon … threw a poetry over every thing, which reached and glowed in the heart, in spite of intense frost and biting breeze. At such a time we were wont to pull on our warm jackets and seal-skin caps.’27 This ‘striding out upon the floe … under so bracing a climate’28 and looking down on the ‘squadron’ from the ‘heights of Griffith’s Island’29 reveals the experiential element of the sojourners’ stay in winter quarters. The practicalities described – clothing, physical movement through the environment, and emotions – are in contrast to the panorama that Osborn then revisited over forty-four lines, like a guide, for the benefit of the reader:

Imagine yourself, dear reader, on the edge of a lofty table-land … fancy a vast plain of ice and snow, diversified by snow-wreaths, which, glistening on the one side, reflected back the moonlight with an exceeding brilliancy, whilst the strong shadow on the farther side of the masses threw them out in strong relief. Four lone barks, atoms in the extensive landscape, – the observers’ home, – and beyond them, on the horizon, sweeping in many a bay, valley, and headland, the coast of Cornwallis Island, now bursting upon the eye in startling distinctness, then receding into shadow and gloom, and then anon diversified with flickering shades, like an autumnal landscape in our own dear land, as the fleecy clouds sailed slowly across the moon, – she the while riding through a heaven of deepest blue … and say if the North has not its charms for him who can appreciate such novel aspects of nature.30

Osborn directs the reader where to look and what to look at, like a tour guide in a virtual landscape. In this way, the reader is encircled by an imaginary fixed panorama, but one that includes ‘home’ for these particular observers. It is probable that Osborn is here playing on his readers’ familiarity with Robert Burford’s popular fixed panorama, Summer and Winter Views of the Polar Regions (discussed in Chapter 4), which was exhibited in London in 1850 and was based on sketches by Lieutenant William Henry Browne from the Ross expedition of 1848 to 1849.

William Hulme Hooper, in Ten Months among the Tents of the Tuski (1853), also invited the reader into his book to share ‘one of the most exhilarating incidents one can experience’: ‘We have just arrived at the head of a bad rapid, and are preparing to “run” it: will you take a seat with us in the boat, reader, and share the striking episode? Come then.’31 Hooper addresses the individual reader directly in the present tense with a sense of immediacy; he invites us to sit beside him in the canoe in the Mackenzie River district with the ‘water bubbling and foaming and roaring around us, spray dashing into our faces’.32 Hooper keeps the reader in the action by periodically urging us to observe: ‘but see, see!’; ‘But look, look!’33 Hooper has gone further than Osborn; his use of the imperative heightens the sense of the occasion as he instructs the reader. Osborn wanted us to imagine a visual experience without the impracticalities of Arctic life; Hooper asked us to take a seat and, over the course of four pages, littered with exclamation marks, the reader imagines feeling physically wet. Osborn’s is visual; Hooper’s requires imagined participation.

In essence, these mid-nineteenth-century authors go further than just picturing the landscape; they exhibit it and invite the reader into an imagined experience. While the authors of these narratives employ visuality, beyond mere landscape description, to engage their readers, first-time visitors and summer visitors to the Arctic often referenced popular visual culture directly to describe sights. Isaac Israel Hayes, in his narrative An Arctic Boat Journey in the Autumn of 1854 (1867), invited the reader into the explorer’s world, via a scene presented as an instructional and ethnological exhibit: ‘If the reader will follow me into the hut he will see there a succession of tableaux which may be novel to him. The two above-mentioned hunters sit facing each other, and facing the lump of frozen beef, which lies upon the ground.’34 When William Parker Snow witnessed Port Leopold, where the Ross expedition had spent the winter of 1848 to 1849, he drew direct parallels with his experience of viewing the panorama Summer and Winter Views of the Polar Regions in London earlier that year:

As we neared the shore, the whole features of the place came fresh upon me, so truthful is the representation given of them by Lieut. Browne in Burford’s panorama. I could not mistake; and, I, almost, fancied that I was again in London viewing the artistic sketch, but for certain undeniable facts in the temperature and aspect of the ice which banished such an idea.35

The interplay here between the represented landscape and the experience of being in the Arctic suggests that the author has been conditioned by visual culture in such a way that he does not privilege the authentic experience. While viewers of the panorama in London could imagine themselves in the Arctic, here, Snow reversed that dynamic, re-imagining himself back in London at the panorama. The panorama was Snow’s primary source, and he projected the Arctic of Burford onto the world he encountered, proving that travellers sometimes see what they expect.36 Humboldt recognised this phenomenon when he noted that spectators of panoramas were immersed in the experience: ‘Impressions are thus produced which in some cases mingle years afterwards by a wonderful illusion with the remembrances of natural scenes actually beheld.’37

As well as presenting the Arctic and its people as an exhibit, authors also regularly turned to Romantic poetry to describe the nature they encountered, and texts were embedded in a web of literary references. Here, Osborn was not content with conveying an exciting scene with crisp active verbs and breathless punctuation for the reader. He felt it necessary to romanticise the novelty of the ice by using the words from Coleridge’s ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ to communicate his own personal experience:

June 24th, Baffin’s Bay. – The squadron was flying north, in an open sea, over which bergs of every size and shape floated in wild magnificence. The excitement, as we dashed through the storm, in steering clear of them, was delightful from its novelty. Hard a starboard! Steady! Port! Port! you may! – and we flew past some huge mass, over which the green seas were fruitlessly trying to dash themselves. Coleridge describes the scene around us too well for me to degrade it with my prose. I will give his version: –

Hooper, too, recalled the ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ when their journey was halted by ice: ‘We had a full view of the impossibility of a present advance, – “The ice was here, the ice was there, / The ice was all around.”’39 In fact, Coleridge had based his visualisation of ice on earlier narratives of exploration and the perils they could entail.40 In particular, the influence of James Cook’s second voyage, in which the Resolution was the first ship to cross the Antarctic Circle in 1773, on Coleridge’s poem was highly likely, as William Wales, the expedition astronomer and meteorologist, taught at Christ’s Hospital School during the time in which Coleridge was there.41

Finally, referencing their own memories of England to aid their description of landscapes was not an uncommon feature of Arctic narratives. It has been argued that the appropriation of the English landscape into the Arctic by British naval officers in the nineteenth century betrayed a lack of comprehension of the Arctic environment, which could even lead to disaster.42 Osborn was no exception, and he did indeed use the English countryside to describe the scene to his readers. Near Melville’s Monument, on the west coast of northern Greenland, he used the English landscape as a simile: ‘a firm unbroken sheet of ice extended to the land, some fifteen miles distant. Across it, in various directions, like hedge-rows in an English landscape, ran long lines of piled-up hummocks, formed during the winter by some great pressure.’43 However, it is equally possible that, in this case, Osborn did so for the benefit of a readership that would never travel to the Arctic, rather than to aid his own comprehension of the landscape. Ann Radcliffe defended her use of this technique in her account A Journey Made in the Summer of 1794, when she clarified that ‘one of the best modes of describing to any class of readers what they may not know, is by comparing it with what they do’.44

Other environmental and experiential memories that appear repeatedly in British Arctic narratives, perhaps surprisingly, are those of exotic places far from the shores of both Britain and the Arctic. The tropics, where many of the Arctic officers had recently served on surveying missions, provided a surprisingly useful, often contrasting, reference point.45 In Ten Months among the Tents of the Tuski, Hooper realised that Arctic nights can be as ‘charming’, although very different, as those in hot climes:

The harbour is freezing over fast, with the water as smooth as glass: a bright moon and cloudless starlit sky render the scene one of the most perfect for tranquil beauty I can remember ever to have witnessed; yet here are no trees, no woods, no foliage to enliven the view; – all is snow-clad; mountains and rugged hills frowning in their majesty where thrown into deep shade, and assuming with the headlands and slopes strange fantastic shadows, jutting out in bold relief on the silent water. So, after all, there may be other than tropic nights charming.46

Like other narrators who had been employed in the Pacific, Osborn used the Arctic to imagine its antithesis, by connecting memory and sentiment. While observing the geology of the limestone cliffs of Devon Island with their ‘numerous fossil shells, Crustacea, and corallines’, he and his companions were sentimentally transported ‘back to the sun-blest climes, where the blue Pacific lashes the coral-guarded isles of sweet Otaheite, and I must plead guilty to a recreant sigh for past recollections and dear friends, all summoned up by the contemplation of a fragment of fossil-coral’.47

The Environment Made Visible: Icescapes and Landscapes

The Arctic environment ‘placed on view’ prompted a wide variety of published aesthetic responses from the expedition members in the years of the Franklin searches. These reactions, transmitted through the descriptive passages and illustrations, were tailored for their expected readership. The language employed and illustrations printed made the Arctic visible for readers of the narratives. Never before had so many areas of the Arctic, from the Chukchi Peninsula to the southern tip of Greenland, been described, denounced, or admired. Not all regions of the Arctic were aesthetically pleasing to the nineteenth-century eye or deemed suitable for illustration. A lack of visual novelty was associated with the western reaches of the passage, for example. Although there is considerable climatic and topographical variation, the public perception of the Arctic was as ‘a dangerous zone where visitors risked their lives’.48 The map (Figure 3.1) shows the geographical spread of the regions described in the narratives. Some voyages produced narratives by two authors, and it can be seen that 70 percent of all published narratives during this decade covered the Atlantic approach to the archipelago via Baffin Bay and Greenland, which corresponds to the approximately 70 percent of search ships that approached from the Atlantic.

The immense icebergs of Baffin Bay, in particular, calved from Greenlandic glaciers,49 elicited wide ranges of responses varying from disgust to delight. Despite the fact that numerous whaling ships visited Baffin Bay during summers in the nineteenth century, this region is visualised almost as another world in the search narratives. Robert Goodsir, who sailed to the Arctic on a summer whaling cruise with Captain William Penny in 1847, alluded to Edmund Spenser’s late sixteenth-century poem The Faerie Queene when he enthused: ‘it is impossible to describe the beauties of these ice islands … The imagination of Poet or Painter never fancied grotto fitter for a Fairy Queen than these would be, could but the beauties of the Floral world be associated with them.’50 Goodsir saw a landscape both picturesque and medieval, his ice grottos replacing the ruined castles so popular in the picturesque mode.

For William Parker Snow, on the first Arctic voyage of the Prince Albert in 1850, a delicate icescape unfurled like a panoramic fairy tale. His published narrative, Voyage of the Prince Albert (1851), based on a summer search, was illustrated with four soft, delicate colour lithographs. The ‘Prince Albert’ Surrounded by Icebergs (Figure 3.2) resounds with the more positive and fairy-tale qualities of Snow’s text and shows a dream-like icescape, likely based on an image constructed after the voyage and incorporating a large proportion of his imagination. The closely clustered ice of the background, although pointed and sharp, is rendered in soft, pastel tones, creating a nebulous appearance that jars with the potentially dangerous situation. This softness reflects the author’s delight in the Arctic icescapes as expressed in the textual description. However, the seductive appearance of the ice could be seen to have parallels with fairy tales in which danger and supernatural power is disguised as something ambiguous, like the gingerbread house in the woods.51

Figure 3.2 William Parker Snow, The ‘Prince Albert’ Surrounded by Icebergs, Voyage of the Prince Albert, 1851. Colour lithograph, 12.5 × 20 cm. Frontispiece of Snow, Voyage of the Prince Albert in Search of Sir John Franklin: A Narrative of Every-Day Life in the Arctic Seas (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1851).

In contrast, Commander Edward Augustus Inglefield, whose narrative related a summer in the Arctic on the small screw schooner52 the Isabel in 1852, described the icebergs of Baffin Bay as ‘rude and grotesque’.53 Indeed, they become personified, ‘like “grim watchmen” of the bay, scowling on the adventurous stranger who would tempt these dread shores’ in the sea off Cape York, on the west coast of Greenland.54 This negative personification of the Arctic landscape repeatedly occurs in some narratives, leading to an image of Arctic geology as a harsh entity that eternally ‘frowns’ at readers.55 This kind of anthropomorphising of rock occurs in gothic novels like Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), when the female protagonist, Emily, sees the villain Montoni’s castle for the first time: ‘Silent, lonely, and sublime, it seemed to stand the sovereign of the scene, and to frown defiance on all who dared to invade its solitary reign.’56 Inglefield’s terse descriptions of the Arctic are presented to the reader with the implication that his summer voyage was in fact as perilous as expeditions that spent longer periods in the Arctic. His emphasis on new discoveries, on-the-spot sketching, and inaccuracies in previous charting suggests his need to justify his endeavour and this publication.57 Keeping his narrative formal and stressing scientific accuracy, Inglefield cannot resist the language of the negative sublime, creating a malevolent visual image of the Arctic that both attracted and repelled. Ultimately, he writes himself as the heroic explorer against the ‘dread’ Arctic, aligning himself with a polar sublime and ‘partaking of the sublimity against which he matched himself’.58

Although the narrative contains only five illustrations, the pictures chosen for print tell an independent story by using the triadic canon of motifs to highlight both danger and discovery. The illustrations Killing a Bear off Cape York and Dangerous Position of the ‘Isabel’ Caught in the Lee Pack serve to emphasise the masculine activity and danger associated with Arctic voyages; the visual image of a leaning ship caught in pack ice is a ubiquitous motif in Arctic publications, signifying peril and the possibility of disaster.59 However, the calm and tranquil fold-out panoramic print that illustrates Inglefield’s apparent discovery of the entrance to the ‘Open Polar Sea’, Midnight Aug 26th 1852, as well as the frontispiece, ‘Isabel’ Entering the Polar Sea through Smith’s Sound, Midnight, show a benign Arctic, suggesting an entrance to a hidden paradise:60 ‘We were entering the Polar Sea … plying onward in the unfreezing Polar Basin.’61 Inglefield was, of course, completely mistaken, and the theory of an unfrozen sea surrounding the North Pole was later invalidated.

First-time visitors who overwintered on ill-prepared expeditions also created extreme visualisations of the Arctic environment, attributing an almost supernatural quality to a geographical region. As Craciun shows, with regard to Franklin’s account of his disastrous Arctic land expedition, Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea (1823), distressing ordeals had the potential to become narratives and then commodities.62 A narrative that included ‘starvation, murder, cannibalism, and madness was tailored to please an audience already schooled in Gothic romances, captivity narratives, shipwreck accounts, early ethnography, and travel writings.’63 The American Grinnell expeditions, unprepared and badly planned,64 were already best-selling narratives waiting to happen. Elisha Kent Kane’s Arctic Explorations (1856) was praised by a reviewer as a demonstration of human endurance; the ‘terrible record of suffering’ was ‘almost too horrible to read’.65 Isaac Israel Hayes, on that second Grinnell expedition led by Kane, imagined his ‘home-world’ when trying to escape the Arctic, suggesting that for him the Arctic was another world: ‘Far behind that dreary mist lay our home-world, gladdened by a genial sun – glowing in the gold and crimson of its autumn. The pictures which our fancy drew made such contrast with the realities of our situation, that we fell to scheming again for our deliverance.’66 Hayes’s imprisonment in the Arctic, unable to escape, echoes the captive trope of Gothic novels, lending the appeal of excitement to the respectability of an expedition narrative, all the more thrilling for its basis in reality. Although Hayes used the term ‘home’ to refer to their temporary hut throughout the text, his ‘home-world’ is the place to which he yearned to return. His use of the term ‘dreary’ is typical of Arctic narratives; it was a common adjective that had become associated with landscape and particularly with the landscape of the North since the eighteenth century, for example, in James Beattie’s The Minstrel (1771), ‘the chill Lapponian’s dreary land’ connects the adjective to winter in Lapland.67 The strong connection of the word ‘dreary’ with the Arctic was compounded by the Romantic poet and political commentator Robert Southey, whose Life of Nelson (1813) was included in the library of the Assistance during the Belcher expedition.68 As a young boy, Nelson had participated in Phipps’s Arctic voyage to Spitsbergen (now Svalbard), and, although Southey drew on Phipps’s narrative for his description of the environment, the former introduced descriptors such as ‘dreary’ to describe the Arctic in the Life of Nelson. This influential and imperialist book was ‘one of the texts by which Romanticism educated the British in an ideology of empire’.69 However, it is notable that the term ‘dreary’ is not one that is used in Phipps’s original book.70

By contrast, authors who participated in relatively well-organised expeditions and spent several winters in the Arctic became inured to it and felt more at ease in the environment.71 Their winter ‘imprisonment’ in the ice-bound ship reads more like a retreat from civilisation, in fact they often use the word ‘sojourn’,72 implying a restful stay and aligning with the idea of travel as an escape from civilisation.73 Lengthy descriptions of landscapes lessen when the explorer is embedded in the environment. For example, McClintock participated in four northern voyages between 1848 and 1859, experiencing a total of six winters in Baffin Bay and the Canadian archipelago.74 For this reluctant author, aided by Osborn who ‘[saw] it through the press’, ‘lofty’ is the only term in his book that approaches a romantic aesthetic when the mountains of Greenland or Baffin Island appear.75 This stock romantic adjective produces images of high mountain peaks, wreathed in mist in the mind of the reader. It is likely that the cause of McClintock’s apparent lack of ‘aesthetic interest in nature’76 was his familiarity with the region, having spent much of the 1850s between Greenland and the Canadian archipelago.

Furthermore, the knowledge of the topography of local areas where ships had wintered caused the landscape to be experienced with new meaning and even with affection by those returning to the region. McDougall, returning to the Arctic for the second time on the Kellett arm of Belcher’s squadron in 1852, noted how the landscape became familiar and now held new significance:

The sight of Griffith’s Island, as may be supposed, afforded a peculiar interest to those who, forming a part of the expedition under Captain Austin, had spent eleven months, frozen up in its immediate neighbourhood. Every point, hill, and ravine, was connected with some little incident, during our rambles over its desolate, and uninteresting surface.77

McDougall here eschews the popular term ‘imprisonment’ for the phrase ‘frozen up’, also favouring ‘neighbourhood’, a word describing a local, familiar area, a place with meaning as opposed to a landscape. Here, the landscape has become a locality. It is no longer described in pictorial terms. No textual description leads the eye from the foreground towards the horizon. Instead the island is a local place, infused with personal memories triggered by its sight. ‘Every point’ is connected with ‘some little incident’, suggesting the many small occurrences that made up the life of the expedition in winter, and the choice of the noun ‘rambles’ evokes a leisurely walk undertaken for pleasure, associated with a sense of freedom and childhood adventure. The place, despite its ‘desolate, and uninteresting surface’, is now of ‘peculiar interest’ because of the emotional attachment that McDougall and his fellow former members of the Austin expedition feel. The members of Horatio Austin’s expedition are also bound to each other by their links to the island, marking them out as a distinct group, separate from those who were new to the neighbourhood. McDougall’s inclusion of the phrase ‘as may be supposed’, which connects with what he imagines are his readers’ suppositions regarding the sight of the island, implies that he assumed his readers would understand this intimacy with the environment.

Although places like Griffith Island may have seemed topographically ‘uninteresting’, published narratives needed to include eye-catching illustrations. These incorporated clear visual prompts that could transport readers pictorially to the polar regions. Inevitably, these include ice and snow in abundance. Even summer visitors focused on the more dramatic nature of the ice to seduce readers, while greenery was rarely depicted in the published illustrations. This is despite the fact that most outdoor sketching on these voyages was done between May and September, during the Arctic summer, when vegetation appeared. The visual preoccupation with ice and snow no doubt accounts for the misconception, prevalent today, that Arctic regions are perpetually snow-clad.

Elisha Kent Kane’s first Arctic narrative took this to an extreme with the Inspector’s House – Lievely depicted as covered in snow, unlikely on the west coast of Greenland in late June when Kane visited and indeed not mentioned in the text that describes his impressions of Lievely (Qeqertarsuaq) and his description of the house on subsequent pages.78 In the picture, the snow falls heavily, and icicles hang from an adjacent structure. While the brief and undated caption leaves much to the imagination, the associated text of the chapter unsettles the illustration. Although ‘snow, as usual, covered the lower slopes [of the hills]’, Kane found a profusion of flowers and berries like ‘a carpet pattern of rich colours’ behind the settlement. He declared: ‘The Arctic turf is unequalled: nothing in the tropics approaches it for specific variety’.79 Despite the extensive use of prints in Kane’s books, not one depicts Arctic flora, for example, preferring instead to highlight sharp peaks, ships leaning at acute angles, and immense icebergs, suggesting the terror associated with the sublime. The exclusively monochrome illustrations in his narrative leach any colour from the Arctic and show a landscape only in terms of dark and light. A note at the beginning of Kane’s narrative explains that the author was unable to revise the book before it was published, as he departed on his second Arctic expedition in May 1853,80 which may account for some of the jarring disconnection between text and picture.

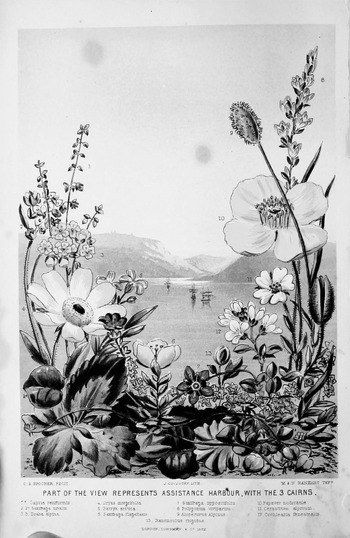

An unusual visual representation of flora exists in the Arctic narratives of this period. It must have surprised the reader used to being presented with icebergs and snow or desolate hills. Peter Sutherland, the surgeon on the Penny expedition of 1850 to 1851, included a colour representation of Arctic flora in his narrative.81 Although the expedition wintered near present-day Resolute, deep in the Canadian Arctic archipelago, the collection of flora is set against the backdrop of an ice-free Assistance Harbour. This comparatively expensive book (twenty-seven shillings), in two volumes, was aimed at a more scientific audience.82 A Group of Thirteen of the Flowers most Commonly Found around Assistance Bay (Figure 3.3) is one of six colour lithographs used to illustrate the narrative. Although the flowers are included as ‘specimens’, the inclusion of their environmental context in the background associates them clearly with the Arctic.83 The bright and fresh species of Arctic flora in bloom takes up most of the picture, while also acting as a frame for the ships, which become small and insignificant in the distance.

Figure 3.3 Peter C. Sutherland, A Group of Thirteen of the Flowers most Commonly Found around Assistance Bay, 1852. Colour lithograph, 17.8 × 11.6 cm. Plate 4, vol. 2 of Sutherland, Journal of a Voyage in Baffin’s Bay and Barrow Straits … in Search of the Missing Crews of H.M. Ships Erebus and Terror, 2 vols. (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1852).

This unique representation of an Arctic summer, and its pockets of verdant lushness, has little illustrative parallel among the body of narratives of the Franklin search expeditions. Although textually we find references to such scenes, prints of flora, small and feminine, presumably were not wholly compatible with the masculine image of the search. In his introduction, Sutherland thanked ‘the artists employed upon the illustrations’. He furthermore trusted that ‘the public will appreciate the arrangement and skill of the lady who has, from dried specimens, presented them with a plate, exhibiting the most abundant species of the thinly-scattered flora of Cornwallis Island’.84 That the ‘lady’ is separated from the ‘artists’ who worked on the other illustrations corresponds to the separation of the flora from the more typical Arctic scenes in narratives and its association with femininity.

Although many authors commented on the plant life found in the Arctic, such scenes were not generally illustrated in the narratives. McClintock noted that on the west side of Baffin Bay, near the entrance to the Northwest Passage: ‘Upon many well-sheltered slopes we found much rich grass. All the little plants were in full flower; some of them familiar to us at home, such as the buttercup, sorrel, and dandelion.’85 Osborn’s written descriptions also include the Arctic summer, when in July of 1850 he amused himself on the Duck Islands near Devil’s Thumb by ‘picking some pretty Arctic flowers, such as anemones, poppies, and saxifrage, which grew in sheltered nooks amongst the rocks’.86 This briefly glimpsed floral vision was wholly incompatible with the icy wastes that had become associated with the polar regions in the early nineteenth century, through texts like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) and Radcliffe’s poem ‘The Snow-Fiend’, published in 1826, in which a ‘vengeful’ being rules the North with a ‘savage eye’:

Summer visitors tended to have the most polarised reactions to the environment, as the scenery for a fairy tale or as an openly hostile landscape. These authors conveyed the most other-worldly images for their readers. Those on unsuccessful expeditions, like Hayes, were anxious to convey their perceived harshness of the environment and presented a negative Arctic sublime, heavily coded and pictorialised for the reader. Conversely, authors who spent more time in the Arctic, especially some who had relatively successful winter sojourns, portrayed it in more practical terms, and sometimes with comfortable familiarity, suggesting that they no longer viewed it as a formal landscape presented for view (or a series of pictures), but became embedded in their locality. For those authors who wintered in the Arctic repeatedly, the landscapes ceased to be framed pictorially and became localities imbued with emotional resonance through personal and experiential knowledge of the region.

Representing Indigenous Peoples

The depictions of the Arctic did not feature the physical environment alone but also, on occasion, Indigenous peoples who lived there. A major visual feature of all maritime Arctic travel narratives during the Franklin search is the image of the Northern inhabitant that was transmitted to the ‘civilised’ world. Travel literature helped to shape conventions of the representation of various ‘races’, both by the showmen who exhibited actual people in popular, and accessible, displays during the nineteenth century and by the public who interpreted the shows; travel literature provided a resource of descriptive information used to contextualise such exhibitions.88 Ethnologists were also reliant on travel narratives for information on ‘races of the world’.89 This picturing was committed to the published record safe in the assumption that the Indigenous person would never read the book in which they were described. By the 1840s, ethnology had emerged as a discipline that used ‘physical, social, and linguistic features’ to study human variation.90 James Cowles Prichard, who wrote the chapter ‘Ethnology’ in the Manual of Scientific Enquiry (1849),91 recommended that the traveller study ‘all that relates to human beings’ in ‘remote nations’,92 with attention to physical characteristics, society, and language, poetry, and literature. Inuit had been sensitively represented by the ethnologist, surgeon, and Arctic explorer Richard King, who published a series of three articles on their ‘industrial arts’, ‘intellectual character’, and ‘physical characters’ in 1848.93 As Ellen Boucher observes, expeditions had no problem in appropriating Inuit survival techniques, but their debt to Inuit was ‘easily obscured and forgotten’.94

Attitudes to the local populations are starkly representative of their time. In the mid-nineteenth century, the view of the Indigenous person as a ‘noble savage’ was still popular; in this context, ‘savages’ were often viewed in a sentimental manner.95 In the published narratives, the representation of Indigenous peoples in the Arctic, or the characters they often become, is clearly influenced by merging filters of aesthetics, gender, ethnicity, and unequal power relations. While their visibility is sometimes clear, lower ranks of the expedition itself, such as seamen, are shadowy figures in the narratives, known collectively but rarely individually. Attitudes towards seamen, or ‘Jack’ as they were commonly known, even suggest that, in terms of class, some Indigenous individuals were held in higher regard.

There are two major regions in the Franklin maritime search area that can be thought of in terms of Mary Louise Pratt’s ‘contact zones’, which are ‘social spaces where disparate cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination’.96 These are the Inuit communities around Baffin Bay, with which expeditions had passing contact, and the Chukchi, Yup’ik, and Iñupiat areas around the Bering Strait, where expeditions that wintered over had prolonged contact with Indigenous communities. Other areas include the North American mainland and the southern part of the archipelago where expeditions had contact with Inuvialuit and Inuinnait (Copper Inuit). For the search expeditions that approached the Northwest Passage via Greenland and Baffin Bay, their first contact occurred at one of the harbour villages on the west coast of Greenland. The appearance of the settlements, whose residents were sometimes a mixture of Danish and Inuit parentage, often aroused disgust in the first-time visitor due to what was perceived as being squalid living conditions. McClintock, on his fourth Arctic expedition, was more respectful in his descriptions, although admitting that when they employed a young man as their dog-driver he was ‘cleansed and cropped … soap and scissors being novelties to an Esquimaux’.97 Further north along the west coast of Greenland, McDougall recorded his impression of the appearance of two Inughuit men and three boys near Cape York (Perlernerit): ‘they outvied all we had previously seen in want of cleanliness, and were, without exception, the most disgustingly filthy race of human beings it has been my lot to encounter’.98 Such statements often carry an underlying tone of delight as if their judgement confirms their own superiority.

Terms like ‘specimen’ and ‘race’ were common in ethnological discourse at the time. ‘Race’ referred to human variation, though increasingly during the 1850s and 1860s a ‘new tide of Victorian racism’ meant that the conceptualisation of the term became associated with fixed, inherited traits that could not be changed.99 Prichard variously used the terms ‘race’, ‘type’, and ‘tribe’ in his chapter, although he also referred to nomadic peoples as ‘savages’; the term ‘specimen’ was used with reference to collecting human skulls, if it was possible to acquire any.100 Visual assessment by Goodsir, a surgeon, describing the people encountered at the Whale Fish Islands (Imerigsoq), tends to take the form of natural history description, to which ethnology was closely related: ‘the large head, with narrow retreating forehead, strong coarse black hair, flat nose, and full lips, with almost beardless chin’.101 This analytical description of the Inuk as a specimen distances the reader, and indeed the author, from any personal engagement with the people. Goodsir homogenised Inuit, separating his ethnological portrait from the narrative, a technique that is noted by Mary Louise Pratt.102 These descriptions were designed to focus on difference and fed into the hierarchical categories of racist ideology.

The illustrations in the narratives of some visitors to the Arctic mirror this visualisation of the Indigenous person as a type, and depictions of unnamed individuals like that of Inglefield’s narrative are common, stripping the person of their individuality. Such images foreshadow the later dehumanising photography of Indigenous peoples, such as that of the 1860s taken in South Africa according to the instructions of Thomas Huxley. Huxley complained that many photographs, which had been taken by travellers, were useless for discerning their physical characteristics and advocated photography of models unclothed with a measuring stick, facing forward and in profile.103 The female Inuk illustrated in Inglefield’s narrative is a servant, unnamed and anonymous.104 Here, clothing and physical appearance dominate, emphasising features that are characteristic of a group and not of an individual. Her docile appearance is further domesticated by the tray she carries, complete with the European trappings of wine glass and bottle, in place of traditional Inuit artefacts.

For Atlantic-approaching expeditions that overwintered in the Arctic (such as the large Austin and Belcher expeditions), their winter sojourn, commonly in the Parry Channel, was far removed from the possibility of extended interaction with local populations over long periods. This was because the nearest Inuit populations resided to the east, on the coast of Greenland, and on the more southerly islands of the Canadian archipelago. As Cavell notes, the northern half of the Canadian archipelago was abandoned by Inuit in the early part of the Little Ice Age (c. 1300–1870);105 thus the narratives’ assessment of the Indigenous people usually ends on the west coast of Greenland, and the empty environments thereafter represented were indeed largely devoid of a local population for much of the year.

Expeditions that approached the Northwest Passage from the west via the Pacific Ocean and Bering Strait had more prolonged contact with Indigenous peoples. The expeditions often wintered near Chukchi and Iñupiat settlements, where prolonged interaction took place over the winter or even successive winters.106 Such interactions are evident in Hooper’s Ten Months among the Tents of the Tuski,107 written by the lieutenant of the Plover who was in the Arctic from 1848 to 1852. The bulk of his narrative concentrates on the time the expedition spent with the Chukchi and is clearly reflective of the extensive hospitality he experienced. Hooper’s written descriptions of individual Chukchi are character sketches as well as being physically descriptive. Furthermore, the inclusion of Ahmoleen’s Map of Behring’s Straits signals the extent to which expeditions benefited from Indigenous knowledge.108 The plates show an Arctic environment that includes Chukchi and expedition members, while the value of the social interaction with the Chukchi is evident both in the language used and the illustrations.109 For Hooper, the environment and people’s ‘many points of striking interest had become familiar’, but a ‘new and delightful spectacle’ was provided when ‘to crown it all, the new arrivals, with their reindeer, filled up the picture which needed nothing more to complete its picturesque and peculiar beauty’.110 The use of the term ‘picturesque’ here equates to the unthreatening novelty and pleasing irregularity associated with Uvedale Price’s interpretation of the aesthetic.111

Although the scene was described as a ‘tableau’ featuring these new arrivals, this is a scene that includes ‘the crew, clad in all varieties of costume, from the semi-military to a close proximity with the dresses of our friends, mingling with the Tuski in their curious habiliments’.112 These figures in Winter Quarters, Emma’s Harbour (10.5 × 17.5 cm) are solid and at ease in their environment, showing none of the struggle we associate with some of the expedition figures in other prints. This heavily populated landscape is starkly different to the empty landscapes that Pratt suggests were produced by ‘the European improving eye’ of late eighteenth-century writers in Africa.113 It is also distinguished by the inclusion of expedition members as part of the ‘tableau’, marking it out as different from the tableaux of purely Indigenous people that were popular metropolitan exhibitions at the time. Furthermore, the ship, covered in for winter, is shown in the background. Unlike representations of the Arctic in summer, which often show land viewed from the ship’s deck, here a view of the ship is seen from land, as the residents would have seen it, albeit from a raised perspective.

This depiction of visitors and residents mingling is also in sharp contrast to an illustration of officers much later in the narrative when a more difficult period in the voyage was experienced – Hooper’s stay at New Fort Franklin, when a small party of men wintered in relative isolation in the continental interior. The illustration is small and cramped, the depiction of the officers at one of the log cabins in the interior showing tiny figures, dwarfed by dark fir trees, indicative of the difficult period in Hooper’s voyage that this picture represents.114 Unusually, the book includes an engraving of a drawing done by Enoch, another Chukchi friend, of Hooper himself, providing a rare example of the lens turned on the author (10.5 × 17.5 cm).115 This is the most intriguing illustration in Hooper’s narrative, the portrait of the ‘explorer’ himself, appearing as helpless and small as an infant and in need of care and assistance, perhaps reflecting the Chukchi view of the outsiders.116

Interaction with Indigenous peoples provided relief from the purely homosocial environment of the ship, and Indigenous women were subjected to additional aesthetic and sexual appraisal. The appeal, or otherwise, of their appearance was commented upon, and they are sharply divided into categories based on age. Goodsir, who describes Inuit men in Greenland in scientific, objective terms (his focus on their physical characteristics belies his medical background), shifted his attention when it came to Inuit women, who were rather judged in terms of their visual appeal, or lack thereof: ‘A number of Esquimaux women were standing on the rocks when we landed. Some of the oldest of them were certainly the most hideous-looking creatures I ever saw, although one or two half-caste girls amongst them were almost comely.’117 McDougall, too, commented on the older women unfavourably at Cape York (Perlernerit) in the north of Greenland:

The inhabitants consisted of two old women, who might have been belles in their younger days; if so, their present personal appearance would tend to prove beyond a doubt that beauty is but fleeting. Three younger and more comely women, each with a child at her back, were presumed to be the wives of the only three men we observed.118

This is a common way of looking in the narratives, in that there are two types of gaze cast upon Inuit. The first gaze judges whether the Inuit man can be transformed into a ‘civilised’ member of society; it compares the Inuit man to oneself. The second gaze is aesthetic or sexual. While young women are often described as ‘comely’ in the narratives, older Indigenous women tend to be regarded as ‘hideous’, a term that does not generally attach itself to descriptions of older men. The use of the word comely, a common nineteenth-century term indicating a person of pleasing and pretty appearance, describes a more picturesque appearance that is quite different to beauty, but nonetheless pleasant to look at, much in the same way that an irregular landscape might be picturesque but not beautiful. In the nineteenth century, the term ‘comely’ was applied to men as well as women.119

Hooper veered close to the supernatural in his description of an old woman when he described a traditional dance where ‘an aged woman with shrivelled limbs, and hideous puckered visage, essayed a feeble exhibition, crooning out also in a thin and shaking tone, and concluding her deed of might with a grin of horror’.120 This ‘exhibition’ inspired a range of emotions, including pity, although Hooper’s old woman was ridiculed in the end: ‘we laughed loudly and long, at which … [she] cackled to herself in high glee’.121 The description of the cackling old woman – ‘hideous’, with her ‘grin of horror’ – aligns itself to the witch archetype of fairy tales.

Although Hooper continued to judge women by appearances, he also considered the character of individual Chukchi women. He considered that his ‘friend’ Yaneenga was ‘one of the best and worthiest specimens of her tribe’, although other, younger women might ‘dispute with her the palm of beauty … but, who, like Yaneenga, bore so unvaried a countenance of good-humour? – who, like her, was always amiable, always thoughtful for the wants or comforts of those around her?’122 While Hooper referred to her as a ‘specimen’ of her ‘tribe’, using the language of ethnology, he praised her character above appearance and thought of her as a ‘faithful friend’.123 She and her family appear throughout the relevant portion of the narrative as important and respected figures. These connections with the Chukchi were held in high regard by Hooper, who quotes an early entry from his ‘private note-book’ in his narrative, to show how his impressions of the Chukchi were rooted in what he referred to as friendship: ‘Really we are becoming quite domesticated with these people; they visit our mess-room, and go from cabin to cabin, eat with us, drink with us, and are exceedingly good friends.’124 The use of the term ‘domesticated’ suggests Hooper’s association of the Chukchi with wildness and savagery, and yet his descriptions of Yaneenga hint at the possibility of something rare in the contact zone: a ‘genuine interpersonal relationship’.125

The character of Yaneenga and others in the Bering Strait area make it all the more noticeable that the lower orders on the ship itself do not merit as much attention in the narratives. The seamen on the ships were the lowest rank on a vessel and appear only as shadowy figures in the background of texts. This group, spending far more time with other ranks during an Arctic winter than on a normal voyage, are an often juvenilised generic mass. We might even think of winter quarters as another type of contact zone, where officers and seamen came into deeper contact with each other. Elusive to the modern reader, they are known to us only through general comments. Osborn, for example, juvenilised the sailors when he described a lieutenant relating the voyages of Parry to them during the winter of 1850 to 1851: ‘In an adjoining place, an observer might notice a tier of attentive, upturned faces, listening, like children to some nursery-tale.’126 Indeed, certain Indigenous individuals, in some cases, can be treated with more respect than seamen on the expedition, for their ability to survive in the Arctic as well as for personal characteristics. Seamen, on the other hand, so integral to the expedition, are sometimes portrayed as children, finding fun when they can by sliding down icebergs and praised when they labour in the sledge harness.

An incident related by Goodsir early in his narrative reminds the modern reader of the status of sailors and class divisions on board when two unnamed sailors are lost overboard during an Atlantic storm. The event, while regrettable, does not warrant more than a few lines, and Goodsir purported that the other men soon forgot the incident: ‘sailor-like, in a few days all was forgotten’.127 In common with many other authors of Arctic travel narratives, the sailors here are referred to as ‘Jack’, it not being necessary to name them individually.128 Their individual invisibility suggests that the common seaman was sometimes regarded as an expendable item. In Osborn’s narrative, we see none of the ‘red-faced mortals, grinning, … the men labouring and laughing; – a wilder or more spirit-stirring scene cannot be imagined’.129 Neither is the ‘bustle and merriment’ or ‘gambols of divers dogs … with small sledges attached to them … amidst shouts of laughter’ shown in the plate Sledge Travelling.130 Pictorially, the seamen are only represented as a labouring group, their individual faces invisible to the reader. These men have become representatives of the difficult labour of searching for Franklin.

While first encounters with Indigenous populations were often made visible using descriptors like ‘filth’, they were also viewed in a more scientific way, aligning to the tradition of natural history and the new discipline of ethnology. Indigenous women were made visible in terms of age and appearance; however, long-term contact led to increased interaction in the contact zone. The Plover, for example, was stationed in the Bering Strait region, with some expedition members spending six years in the Arctic. In contrast, the common sailor of the expeditions is almost invisible in the Arctic narratives of exploration, appearing as a group rather than as individuals in their own right, suggesting that some Indigenous individuals were held in higher regard than British seamen.

Intertextuality, Transformation, and Pictorial Commodification of the Landscape

Representations of landscapes change as they move through space and time; the depictions of the Arctic are not fixed, but continuously fluctuating. Sketches were remediated by engravers, lithographers, and publishers. Sometimes, illustrations were created from the author’s textual description, and the original sketch was not necessarily made during the expedition.131 As Qureshi notes (with respect to representations of people), picture and context could easily become divorced from each other in the nineteenth-century circulation of pictures; furthermore, one of an illustrator’s priorities was ‘the creation of a memorable image employing symbols commonly associated with their subject, even if it was at the expense of obvious factual accuracy’.132 The same holds true for the depiction of Arctic environments in print, with the symbols of polar bears, ice, shipwreck (or possible shipwreck), and man-hauled sledge travel occurring repeatedly. As Keighren, Withers, and Bell show, there was a sense among exploration authors in the 1850s that the reading public was ‘saturated with sublime imagery’, ‘indifferent to faithful representation’, and that ‘lithographers had become accustomed to exaggeration’.133 Publishers, for their part, were keen to make a profit and may have directed lithographers and engravers to heighten the impact of a picture.134

The development of new printing techniques and the increased production of illustrated books and periodicals in the nineteenth century is central to contextualising the production of Arctic travel narratives. In keeping with natural history books published in the period, Arctic narratives utilised tinted lithographs, colour lithographs, woodcuts, wood engravings, and mezzotints. Several printing methods are sometimes used in the one book, for example in Kane’s first Arctic narrative, which contained mezzotints, lithographs, and wood engravings.135 Mezzotints facilitated a wide tonal range, making the rendering of contrasts subtle and atmospheric. When comparing publications that are a decade apart, we need to be mindful of such matters as printing costs, the number of colours used, and factors governing the production of the prints. For example, while it was common for professional artists like J. M. W. Turner to have their paintings converted into prints, they would have personally overseen this transformation. A naval lieutenant and amateur artist did not have the same power over his artwork once the expedition returned, particularly when he was not the book’s author, as was often the case. Thus, prints, in their varying forms, do not necessarily represent expedition members’ visual perceptions of the Arctic but were mediated by engravers, lithographers, and publishers.

In Osborn’s Stray Leaves from an Arctic Journal (1852), which went through several editions, the first edition had a folding map, four colour lithographs, and five monochrome engravings.136 The inclusion of a map was seen as a ‘warrant of authenticity and of accomplishment’ by the explorer.137 In the preface, Osborn acknowledged the work of two other officers who were on the voyage, thereby also conferring authenticity on the illustrations: ‘To Lieutenant W. May and Mr. McDougall, I am much indebted for their faithful sketches.’138 The illustrations were printed by the well-known lithographic printing firm, M & N Hanhart, who specialised in natural history plates, landscape scenery, and pictorial covers of sheet music for popular songs in the Victorian period.139 Should the Victorian reader only choose to look at the plates in this book, they would already gain a good understanding of some of the themes of a maritime Arctic voyage. Many of the crucial signifiers are here: exploration, as represented by landmarks; possibility of shipwreck, depicted by ships breaking through sea-ice; and masculinity, represented by sledge-hauling in a snowstorm.

The frontispiece, Cape Hotham (9.3 × 15 cm), depicts a topographical landmark on Cornwallis Island, Barrow Strait, deep in the Canadian Arctic. The short caption is likely aimed at the ‘general reader’140 to whom Osborn referred in his preface. At the same time, naming the location lends it authenticity. Although the scene is relatively tranquil, there is a significant quantity of sea-ice evident. The sky is tinged with evening hues of yellow and pink while the black smoke, connecting to the overall narrative that emphasises the use of the screw steamer, is clearly seen rising from the tender’s funnel. It is likely this picture represents an occasion in August or September 1850 when the ships were in the area.141

There are several points of intertextuality when we examine the subject matter (places and events) of the plates. This frontispiece, Cape Hotham, has a parallel representation in the Illustrated Arctic News, one of the newspapers of the same expedition, in which the picture U.S. Brigs – Advance & Rescue, Passing Cape Hotham142 (6.7 × 13.5 cm) illustrates the ships of the American expedition financed by Henry Grinnell, a wealthy American businessman who funded several private Arctic expeditions. The caption on the latter picture is more specific and refers to events within the environment, not only a notable landmark. The presence of the American expedition is also referred to in Osborn’s narrative: ‘Commander De Haven’s gallant vessels, who, under a press of canvas, were just hauling round Cape Hotham’.143 The two pictures are strikingly similar and represent events that took place within days in September of 1850. However, some obvious differences are evident. The illustration from Osborn’s narrative shows a greater quantity of sea-ice. Additionally, the steam tender and its smoke catch the viewer’s eye in the narrative. Cape Hotham itself is shown from a slightly different angle, an angle that emphasises its distinctiveness as a landmark and makes it appear higher. The transformations are fairly subtle, however, and a link to scientific recording and a commitment to topographical accuracy show the strong tradition of naval surveying in Britain.

Reiterations of other landmarks such as the Devil’s Thumb and what would become well-known sights like the three graves at Franklin’s first winter quarters, in various narratives and in other illustrative formats, give us a sense of the fluctuating visualities of the Arctic during this period. For example, the graves at Beechey Island, the first location of a clue to the mystery of the Franklin disappearance, became a key site in the story of the Franklin searches.144 The graves with their wooden headboards were first discovered in 1850 and during that summer became a macabre tourist spot with no less than ten manned search ships, including over three hundred expedition members, in the area.145 This site was the location of the winter quarters of Franklin’s expedition in the winter of 1845 to 1846 and, as well as the graves of three of Franklin’s men, presented traces of a workshop and garden.146 Whether depicted dramatically, playing to the darker aspect of the Franklin search, or sketched as a naval record, the pictures of this site tell us much about the processes of transformation underway in Arctic imagery at this time.

Starkly contrasting representations of this scene exist. Its first public appearance was in the Illustrated Arctic News where the monochrome print, Seamens Graves – Beechey Island focuses on the graves themselves and shows merely the slopes of Beechey Island in the background.147 It was originally hand-drawn by McDougall on the Austin expedition and was then entitled The 3 Graves – Beechey Is.d. The Winter Quarters 1845–6 of the Expedition under Sir John Franklin (8.8 × 14.8 cm);148 the pen-and-ink drawing shows his careful, characteristically neat, and finely delineated line, suggesting attention to detail, with the names of each man written below his respective grave on the picture.149 The picture is more a technical drawing and has no aesthetic aspirations, being a visual record of the graves rather than an emotive response.

The site took on a far more sinister and gothic appearance when it appeared in Kane’s bestselling romantic narrative that made him the ‘icon’ of the search.150 Over several years, Kane had been encouraged by his family to write up his escapades as a young doctor travelling the world, and by the time he went to the Arctic in 1850, he had become adept at turning any story into a thrilling adventure with a veneer of scientific authenticity.151 This plate (Figure 3.4) was one of those engraved by the notable mezzotint engraver John Sartain from drawings by James Hamilton. The subtitle is careful to include the words ‘after a sketch by Dr E K Kane’, conferring authority on the depiction. Entitled Beechey Island–Franklin’s First Winter Quarters, the caption fails to refer to the graves. However, the silhouetted grave markers are dramatically backlit and clearly are the focus of the picture, lending a ghostly atmosphere to the scene. The half-concealed moon adds a sense of mystery, and the peaks of an iceberg on the horizon recall gothic edifices.

Figure 3.4 James Hamilton, after Elisha Kent Kane, Beechey Island – Franklin’s First Winter Quarters, 1854. Mezzotint, 10.4 × 16.2 cm. Plate 4 of Kane, The U.S. Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin. A Personal Narrative (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1854).

The castellated iceberg is in fact quite out of place here; Beechey Island is located on the south-west tip of Devon Island, and the glaciers are all to the east. The icebergs they created were swept out eastwards by the current to Baffin Bay. Any icebergs that enter from Baffin Bay only move as far westward as approximately 85°W, whereas Beechey Island is located at 91.50°W.152 The slopes of Beechey Island are here represented as vertical cliffs, implying that the nature of the landscape is dark and unfriendly. Most curious of all is that the picture shows a night-time scene, although the location was visited in the bright Arctic summer. The choice to re-imagine the scene in darkness was a calculated one, prioritising sensationalism over science, presenting a far more romanticised, gothic, and obscure Arctic. At the same time, the rather haunting beauty of the scene is aesthetically appealing.

Although the graves are not mentioned in the caption, the eye is drawn to their dark silhouettes, adding a sense of mystery and even antiquity to the piece. The individuals buried do not seem important, unlike in McDougall’s sketch where they are named; rather it is the ghostly atmosphere created by graves that lures the viewer in. Although Kane included the grave inscriptions in the narrative, our first introduction to them is when a messenger comes to Captain Penny, who is with Kane on Beechey Island: ‘The news he brought was thrilling. “Graves, Captain Penny! graves! Franklin’s winter quarters!”’153 The lines coalesce with Lambert’s assessment of the narratives of the searches as retelling a ‘big boy’s adventure’.154

The Devil’s Thumb is a feature that appears represented differently in several narratives. Seen twice in Kane’s narrative, the Devil’s Thumb here is tall and sharp, dark and angular, and placed in the centre of the composition.155 In William Henry Browne’s lithograph The Devil’s Thumb, Ships Boring and Warping in the Pack (12 × 18.5 cm),156 the landmark is far in the background behind the main activity of the ships in the ice-pack; even accounting for perspective, it is far less dramatic and vertical than in Kane’s illustration. The caption on Browne’s version includes events within the Arctic environment, whereas Kane’s brief caption only references the landmark’s unusual name, emphasising its novelty. A prose description of the Devil’s Thumb also appeared in Jules Verne’s Captain Hatteras, the fictional account of an imagined Arctic voyage, first published in French in 1864. Referencing the voyages of both Kane and Snow (and by implication their narratives), Verne used the landmark to set a bleak, yet supernatural, stage: ‘The odd form of the Devil’s Thumb, the dreary deserts in its vicinity, the vast circus of icebergs … rendered the position of the Forward horribly dreary.’ Near the ‘ever-threatening Devil’s Thumb’, the ship is put in the ‘critical position’ so familiar to the readers of the Arctic exploration narratives. Here, the icebergs ‘drifted by in the fog like phantoms’. ‘Sometimes, under the action of the storm, the fog was torn asunder, and displayed towards the land, raised up like a spectre, the Devil’s Thumb.’ The chapter culminates with the reappearance of the captain’s menacing and seemingly supernatural dog, which some members of the crew had attempted to murder. This gave the ‘finishing touch to their mental faculties’.157 Verne’s Arctic narrative shows an acute awareness of the atmosphere evoked by the illustrations in Kane’s narratives, the ghostly, other-worldly space that challenged men psychologically as well as physically.

A more dramatic Arctic began to creep into the narratives as time went on, partially influenced by the success of Kane’s narratives but also perhaps by Arctic panoramas that were exhibited during the 1850s. McClintock’s Voyage of the ‘Fox’ (1859), which went through several editions, included illustrations by Walter May, who did not participate in the expedition. A third edition of Voyage of the ‘Fox’ (1869) contained additional illustrations, many of which are of a more dramatic nature than in the first edition. In this later edition, we find that one of the earlier plates has also been removed.158 Walter May’s Moonlight in the Arctic Regions,159 which showed a view of a tabular iceberg160 and a ship in the first edition of McClintock’s narrative, was replaced by an unattributed illustration captioned Moonlight – August 25 1857 in the later edition.161 Although the date within the caption now attempts to lend authority to the picture, the Arctic has been utterly transformed. The new, heightened contrasts of light and dark are unlikely to have been so extreme at high latitudes in August, and the more ordinary, horizontal icebergs have been replaced by a dramatic pinnacle iceberg, which appears as a vertical and gothic fortress of ice, one that bears a striking resemblance to the mass depicted in Melville Bay in Kane’s The U.S. Grinnell Expedition (1854) and is not dissimilar to the gothic iceberg in Beechey Island.162 The clear full moon of Moonlight in the Arctic Regions has become a semi-concealed body, adding an atmosphere of mystery to the Arctic and increasing the resemblance to the moon depicted in Kane’s Melville Bay.

This transformed environment, where dramatically lit Gothic fortresses hint at mystery, suggests new wonders beyond the horizon, and the vertiginous treatment of the ice is key to this gothicised Arctic. Kane’s illustrations are often untitled vignettes that lend the narrative a dream-like quality and place emphasis on the narrative as adventure story, aligning more with Verne’s Captain Hatteras than with an exploration narrative. The illustrations of Kane’s narratives were carefully planned and executed to maximise the sensational elements of the Arctic expedition. So, while British narratives took some liberty in depictions, including alterations from drawing to print, Kane’s narratives reconstructed the Arctic space completely, moving land masses to where they might be better suited (for example, shifting the sea cliffs found in Lancaster Sound closer to the graves), exaggerating heights, and adjusting the contrasts of light and dark to suit a more gothic mood, blurring the boundaries between fiction and ‘reality’.

Conclusion

McClintock’s mind was ‘busy with some sort of magic lantern representation of the past, the present, and the future’163 as he attempted to sleep during the frustrating summer of 1856, when his ship, the Fox, was delayed by pack-ice. The visual culture of the mid-nineteenth century permeated the writing of even the most pragmatic authors of Arctic exploration and travel narratives, affecting not only the ways in which they told their stories for readers but also their own experience of the Arctic. Other authors went to greater lengths, visually inviting readers to experience panoramas, exhibitions, and tableaux through their descriptive passages, as they drew on Romantic poetry and the power of memory to create an Arctic experience for readers.