Disrupted parenting behaviors, including affective communication errors, role/boundary confusion, fearful/disoriented, intrusive/negativity, and withdrawal, affect children's development. Disrupted parenting behaviors increase the likelihood of children becoming dysregulated physiologically (Bernard, Butzin-Dozier, Rittenhouse, & Dozier, Reference Bernard, Butzin-Dozier, Rittenhouse and Dozier2010; Bruce, Fisher, Pears, & Levine, Reference Bruce, Fisher, Pears and Levine2009; Gunnar & Vazquez, Reference Gunnar and Vazquez2001) and of developing disorganized attachments with their parents (Abrams, Rifkin, & Hesse, Reference Abrams, Rifkin and Hesse2006; Madigan, Moran, & Pederson, Reference Madigan, Moran and Pederson2006), yet research is mixed with regard to which forms of disrupted parenting behaviors are most detrimental to children's development (e.g., Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bureau, Easterbrooks, Obsuth, Hennighausen and Vulliez-Coady2013; Main & Hesse, Reference Main, Hesse, Greenberg, Cicchetti and Cummings1990). Further, identifying the mediators of change within interventions aimed at decreasing attachment disorganization is a necessary step in advancing our understanding of how interventions work. Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC; Dozier, Bick, & Bernard, Reference Dozier, Bick, Bernard and Osofsky2011) is an evidence-based intervention that has been shown to improve parenting quality (i.e., increasing parental sensitivity and positive regard, and decreasing parental intrusiveness). However, research to date has not explored whether ABC is successful at decreasing more problematic forms of disrupted parenting behavior (i.e., affective communication errors, role/boundary confusion, fearful/disoriented, intrusive/negativity, and withdrawal). Therefore, the aims of the current study were twofold. First, we aimed to assess whether ABC was effective at decreasing specific types of disrupted parenting behavior when compared to a control condition. Second, we aimed to determine whether disrupted parenting behavior mediated associations between intervention group and disorganized attachment.

Parent–Child Attachment Quality

Attachment quality in infancy represents the expectations that infants have regarding their parents’ responsiveness and availability, and is differentiated by the strategy or lack of strategy children utilize with a parent in stressful situations (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978). Children with organized attachments (i.e., secure, insecure-avoidant, or insecure-resistant) exhibit consistent strategies with their parents during times of stress. Securely attached children use their parents as a source of comfort during stressful situations and are easily soothed. Insecure attachments are marked by behaviors of ignoring parents during distress (i.e., avoidant) or by an inability to be soothed by their parents (i.e., resistant). In some cases, children exhibit a lack of or lapse of use of a strategy in response to distress, which is known as a disorganized attachment (Main & Solomon, Reference Main and Solomon1990).

Organized attachments, especially secure attachments, have long been considered to protect against several maladaptive outcomes, including the development of behavior problems (Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van Ijzendoorn, Lapsley, & Roisman, Reference Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van Ijzendoorn, Lapsley and Roisman2010). Disorganized attachments are identified consistently as a risk factor for later behavior dysregulation above and beyond risk of insecure attachments (Carlson, Reference Carlson1998; Fearon et al., Reference Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van Ijzendoorn, Lapsley and Roisman2010; Lyons-Ruth, Alpern, & Repacholi, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Alpern and Repacholi1993; Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, Reference Lyons-Ruth and Jacobvitz2008; Milan, Zona, & Snow, Reference Milan, Zona and Snow2013).

Caregiving Quality as a Risk Factor for Disorganized Attachment

The quality of caregiving a child receives early in life influences both the development of attachment (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978; De Wolff & van Ijzendoorn, Reference De Wolff and van Ijzendoorn1997) and later social and emotional outcomes (e.g., Sulik, Blair, Mills-Koonce, Berry, & Greenberg, Reference Sulik, Blair, Mills-Koonce, Berry and Greenberg2015). Sensitive parenting has been identified as important for the development of normative regulatory abilities (Denham et al., Reference Denham, Bassett, Way, Mincic, Zinsser and Graling2012; Kopp, Reference Kopp1989) and attachment security (De Wolff & van Ijzendoorn, Reference De Wolff and van Ijzendoorn1997; Verhage et al., Reference Verhage, Schuengel, Madigan, Fearon, Oosterman, Cassibba and van Ijzendoorn2016), whereas insensitive parenting places children at risk for problems with regulatory abilities (Calkins & Johnson, Reference Calkins and Johnson1998; Halligan et al., Reference Halligan, Cooper, Fearon, Wheeler, Crosby and Murray2013). Insensitive parenting is operationalized in many ways within the field of developmental psychopathology and can include withdrawal, hostility, and intrusiveness (Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bureau, Easterbrooks, Obsuth, Hennighausen and Vulliez-Coady2013). However, parental frightening behavior may be even more detrimental to infants’ regulatory abilities than other forms of insensitive caregiving (e.g., Abrams et al., Reference Abrams, Rifkin and Hesse2006).

Main and Hesse (Reference Main, Hesse, Greenberg, Cicchetti and Cummings1990) identified several forms of parental behavior that may be frightening to an infant, which were captured using the frightening behavior (FR) coding system (Hesse & Main, Reference Hesse and Main2006). Specifically, the FR coding system included parents engaging in blatantly frightening behaviors (e.g., growling at the child), dissociating behavior (e.g., entering into a trance), exhibiting fear of the infant (e.g., backing away from the infant), role-reversing behavior, sexualized behavior toward the infant, and timid/deferential behavior toward the infant. These behaviors are believed to be detrimental to children's regulatory abilities because the parent becomes a source of both comfort and fear to the child, creating a “fright without solution” in the child (Hesse & Main, Reference Hesse and Main1999, p. 484).

Since Main and Hesse's (Reference Main, Hesse, Greenberg, Cicchetti and Cummings1990) initial hypotheses regarding parental frightening behavior and later dysregulation in infancy, Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman, and Parsons (Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman and Parsons1999) extended the forms of problematic caregiving that were theorized to affect child outcomes negatively, including attachment quality with their parent, by developing the Atypical Maternal Behavior Instrument for Assessment and Classification (AMBIANCE) coding system. AMBIANCE's coding system includes an overall assessment of parental disruption (both a categorical and a dimensional rating scale), as well as frequencies and dimensional rating scales of each type of disrupted parenting behavior. These include affective communication errors (e.g., failure to respond to infant distress), withdrawal (e.g., using physical or verbal means to distance self from the child), fearful/disoriented (e.g., being frightening to the child, dissociating in the presence of the child), intrusive/negativity (e.g., pulling the child by the wrist, mocking the infant), and role/boundary confusion (e.g., escalating distress of an infant, deferring to the infant for comfort, engaging in sexualized behavior). The AMBIANCE coding system includes the behaviors from the FR coding system, as well as the additional behaviors added by Lyons-Ruth et al. (Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman and Parsons1999). For further information regarding the types of behaviors coded using AMBIANCE, see Haltigan et al., Reference Haltigan, Madigan, Bronfman, Bailey, Borland-Kerr, Mills-Koonce and Lyons-Ruth2019.

A meta-analysis of studies investigating associations between disrupted parenting behavior and child attachment disorganization has reported effect sizes ranging from r = .32 to r = .35, as measured by either Main and Hesse's (Reference Main, Hesse, Greenberg, Cicchetti and Cummings1990) coding system or the AMBIANCE coding system, respectively (Madigan, Bakermans-Kranenburg, et al., Reference Madigan, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van Ijzendoorn, Moran, Pederson and Benoit2006). Yet, as discussed earlier, both the FR and the AMBIANCE coding systems include a wide range of possible parenting behaviors that may have led to attachment disorganization from parental withdrawal (e.g., failure to respond to child distress) to being physically intrusive to the child (e.g., physically pulling child by the wrist when upset), leading to uncertainty as to which forms of disrupted parenting behaviors are most detrimental to development.

Studies examining associations between the unique forms of disrupted parenting behavior and infant attachment disorganization have pointed to dissociation and threatening behavior when using the FR coding system (Abrams et al., Reference Abrams, Rifkin and Hesse2006) and withdrawal when using AMBIANCE (Goldberg, Benoit, Blokland, & Madigan, Reference Goldberg, Benoit, Blokland and Madigan2003). Of note, dissociation is coded in the fearful/disoriented scale of AMBIANCE. Again, due to inconsistencies in research regarding which type of disrupted parenting behavior is assessed, it is not clear as to which form of disrupted parenting behavior may be most predictive of disorganized attachment. For example, when Goldberg et al. (Reference Goldberg, Benoit, Blokland and Madigan2003) assessed whether specific forms of disrupted parenting behaviors (i.e., fearful/disoriented, intrusive/negativity, or parental withdrawal) differentiated children categorized as having an organized versus disorganized attachment, only parental withdrawal significantly differentiated the two, with children who were categorized as having a disorganized attachment having parents that engaged in higher levels of parental withdrawal than children with an organized attachment. In addition, studies have shown that frightening (i.e., fearful/disoriented) behavior directly predicted infant disorganization (e.g., Schuengel, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van Ijzendoorn, Reference Schuengel, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van Ijzendoorn1999). Therefore, studies aimed at identifying which forms of disrupted parenting are most associated with the development of disorganized attachment quality are still needed.

Attachment-Based Interventions

Several attachment-based interventions aimed at improving caregiving quality and attachment security have been developed (e.g., Video-Feedback Intervention to Promote Positive Parenting; Juffer, Struis, Werner, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, Reference Juffer, Struis, Werner and Bakermans-Kranenburg2017; Child Parent Psychotherapy; Lieberman, Ippen, & Van Horn, Reference Lieberman, Ippen and Van Horn2015; Circle of Security; Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, & Marvin, Reference Powell, Cooper, Hoffman and Marvin2014), especially for use among families at risk for negative developmental pathways (e.g., children who have experienced neglect or maltreatment). Most attachment-based interventions have focused on increasing parental sensitivity, rather than focusing on decreasing disrupted parenting behavior (e.g., frightening or intrusive behavior). One intervention that has specifically focused on decreasing disrupted parenting behavior, is the CAPEDP (Compétences parentales et Attachement dans la Petite Enfance: Diminution des risques lies aux troubles de santé mentale et Promotion de la resilience [Parental Skills and Attachment in Early Childhood: Reduction of risks linked to mental health problems and promotion of resilience]; Tubach et al., Reference Tubach, Greacen, Saïas, Dugravier, Guedeney, Ravaud and Guedeney2012) intervention. The CAPEDP intervention is a 44-session home-visiting intervention that begins when parents are approximately 27 weeks pregnant with their first child and follows families through their child's second birthday. Tereno et al. (Reference Tereno, Madigan, Lyons-Ruth, Plamondon, Atkinson, Guedeney and Guedeney2017) found that a smaller proportion of parents who were randomized to receive CAPEDP were classified as being disrupted using the categorical indicator of the AMBIANCE coding system than parents randomized to receive usual care. Further, a smaller proportion of children whose parents received CAPEDP were classified as having a disorganized attachment than children whose parents received treatment as usual. The association between intervention and disorganized attachment was mediated by changes in disrupted parenting behavior. These results provided the first known published study demonstrating that changes in disrupted parenting behavior are associated with decreases in disorganized attachment. Although this study begins to address a clear gap in our understanding of how intervention studies lead to lower rates of disorganized attachment, this study did not investigate the specific forms of disrupted parenting behavior, but rather utilized the overall indicator of disrupted parenting that is heterogeneous across participants, pointing again to a need for further investigation as to which forms of disrupted parenting are most associated with the lower proportion of children with disorganized attachment.

Another attachment-based intervention that focuses on improving disrupted parenting behaviors is ABC (Dozier et al., Reference Dozier, Bick, Bernard and Osofsky2011). ABC is an evidence-based intervention that was developed to promote parental sensitivity and attachment security and is a 10-session parenting intervention conducted in families’ homes. Specifically, ABC focuses on increasing parental nurturance when children are distressed, increasing parental sensitivity and positive regard when children are not distressed, and decreasing frightening and intrusive parental behavior. ABC is thought to achieve these goals through parent coaches’ in-the-moment comments, which provide immediate feedback regarding parents’ use of target behavior during the session (Caron, Bernard, & Dozier, Reference Caron, Bernard and Dozier2018).

Results of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that ABC is efficacious in improving both parent and child outcomes within several high-risk populations including children who live with their birth parents following involvement with child protective services, children in the foster care system, and children who were adopted internationally. Specifically, parents who were randomized to receive ABC demonstrated higher levels of parental sensitivity (Bick & Dozier, Reference Bick and Dozier2013; Yarger, Bernard, Caron, Wallin, & Dozier, Reference Yarger, Bernard, Caron, Wallin and Dozier2019; Yarger, Hoye, & Dozier, Reference Yarger, Hoye and Dozier2016) and positive regard, and lower levels of intrusiveness (Yarger et al., Reference Yarger, Bernard, Caron, Wallin and Dozier2019) than parents in a control condition. Results of RCTs have also shown that children whose parents received ABC exhibit more normative diurnal cortisol rhythms after completion of the intervention (Bernard, Dozier, Bick, & Gordon, Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick and Gordon2015; Bernard, Hostinar, & Dozier, Reference Bernard, Hostinar and Dozier2015), higher levels of executive functioning (Lewis-Morrarty, Dozier, Bernard, Terracciano, & Moore, Reference Lewis-Morrarty, Dozier, Bernard, Terracciano and Moore2012; Lind, Raby, Caron, Roben, & Dozier, Reference Lind, Raby, Caron, Roben and Dozier2017), and stronger emotion regulation abilities (Lind, Bernard, Ross, & Dozier, Reference Lind, Bernard, Ross and Dozier2014) than children of parents in the control condition. Further, children whose parents received ABC demonstrated higher rates of attachment security and organization than children whose parents received the control condition (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012).

The current study aims to extend Bernard et al.’s (Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012) findings that a lower proportion of children whose parents were randomized to receive ABC were classified as having a disorganized attachment (32%) than children whose parents received the control condition (57%) by investigating whether changes in disrupted parenting behavior led to the intervention effects on attachment organization. In addition, although intervention effects have been found related to intrusiveness, no study to date has investigated whether ABC is successful in improving other forms of disrupted parenting behavior (i.e., affective communication errors, role/boundary confusion, fearful/disoriented, and withdrawal).

Present Study

The current study had two aims. The first aim was to assess whether there were intervention effects on disrupted parenting behaviors. Parents randomized to receive ABC were hypothesized to demonstrate significantly less disrupted parenting behavior than parents randomized to receive the control condition, although we had no specific a priori hypothesis regarding which type of disrupted parenting behavior would exhibit intervention effects. Theoretically, ABC targets each of the disrupted parenting behaviors through its use of in-the-moment comments focusing on intervention targets during each session. Specifically, ABC's targets of providing nurturance when children are distressed and responding in sensitive ways when not distressed should be associated with improvements in affective communication errors, intrusive/negativity, and withdrawal. Further, ABC's target of reducing frightening behavior should theoretically relate to improvements in fearful/disoriented behavior, intrusive/negativity, and role/boundary confusion.

The second aim was to investigate whether lower levels of disrupted parenting behavior mediated an association between intervention group and child disorganized attachment. Based on previous research assessing the unique disrupted parenting behaviors that were associated with disorganized attachment, we hypothesized that low levels of parental withdrawal and fearful/disoriented behavior would mediate associations between intervention group and a decreased proportion of children with a disorganized attachment.

Method

Participants

The current sample included 105 mother–child dyads from a large mid-Atlantic city that participated in a RCT assessing the efficacy of a parenting intervention (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012). The current sample is a smaller sample size than previously reported in the Bernard et al. (Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012) paper. Specifically, the current sample included 83.8% (n = 89) of the sample reported in the Bernard et al. (Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012) paper and additional families who completed the intervention after the Bernard et al. (Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012) paper was published (n = 16). Differences may have resulted from difficulties with video quality (e.g., audio not working or video not playing when transferred from tape to digital), missing videos, removal of siblings from the current sample, and removal of fathers per reviewer feedback.

Families were initially referred to Child Protective Services due to substantiated or unsubstantiated reports of maltreatment (e.g., neglect or abuse). All families were enrolled in a city program aimed to keep families intact rather than relocate children into the foster care system. As such, families were referred to study staff to participate in a parenting intervention.

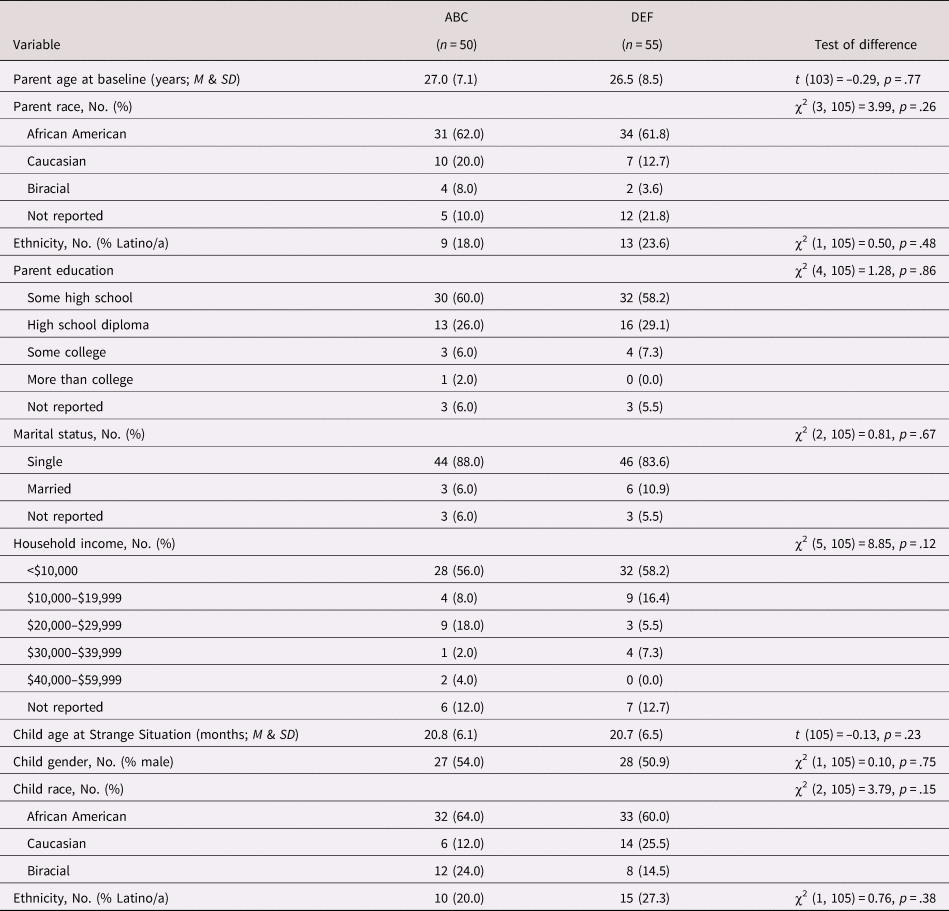

Parents ranged in age from 14.9 years to 47.3 years (M = 26.7, SD = 7.8) at the initial data collection visit, and children ranged in age from 11.7 months to 35.2 months (M = 20.7, SD = 6.3) at the first postintervention visit. All caregivers in the current sample were mothers, and 52% (n = 55) of children were male. The majority of mothers (73.9%) and children (61.9%) were identified as Black or African American with 21% of mothers and 24% of children identified as Latino/a. Demographic variables of interest by intervention group are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between groups on demographic characteristics.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of parents and their children by intervention group

Procedures

Preintervention and postintervention assessments

Approval for the completion of this research was obtained from the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board. After participants were referred to study staff, a preintervention visit was completed. During this visit, the study was explained, consent was obtained, and demographic information was collected. Next, parents were randomly assigned to receive the experimental intervention (ABC) or a control intervention (Developmental Education for Families; DEF).

Data collection

As mentioned earlier, demographic information was collected prior to parents being randomized into ABC or DEF. Next, mothers participated in one of the two 10-session interventions. Outcome data for the present study were collected during an initial follow-up visit after completion of the intervention (M = 7.0 months postintervention, SD = 5.8). This first visit after completion of the intervention was intended to follow the last intervention session within 1 month or at the child's first birthday after completion of the intervention. During this visit, mother–child dyads participated in the Strange Situation.

Interventions

The interventions were matched for duration (i.e., 10-week sessions) and conducted in parents’ homes. Further, experienced interventionists adhered to an intervention manual, and all sessions were video-recorded for later fidelity checks.

Experimental intervention

ABC is a brief parenting intervention aimed at increasing parents’ ability to provide nurturance to their children when children are distressed, respond in sensitive, contingent ways when children are not distressed, delight in their children, and behave in nonfrightening ways. Sessions 1 and 2 focus on discussing the importance of providing children nurturance even when children are not providing clear cues. Sessions 3 and 4 focus on parents behaving in sensitive and delighted ways by following children's lead. Sessions 5 and 6 help caregivers identify and appropriately respond to children's signals while exploring how some play interactions may be frightening and/or intrusive for children. Sessions 7 and 8 focus on exploring parents’ own experiences of being parented and how those experiences may interfere with their ability to meet intervention targets in a supportive context. Finally, Sessions 9 and 10 provide additional opportunities for parents to receive additional feedback and coaching on intervention targets, as well as a time to celebrate parents’ accomplishments.

Control intervention

Developmental Education for Families (DEF) was adapted from previous interventions shown to improve children's gross and fine motor skills, cognition, and language abilities (e.g., Ramey, Yeates, & Short, Reference Ramey, Yeates and Short1984). Components of the initial version of the intervention related to parental sensitivity were removed for this study in order to distinguish it from ABC. Parent coaches discussed and modeled ways to help children reach developmental milestones during the session. Specific activities completed with each child were adjusted according to the child's developmental level.

Measures

Infant attachment quality: Strange Situation (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978)

At the postintervention laboratory visit, parents and their children completed the Strange Situation procedure designed to assess children's attachment security. The Strange Situation procedure consists of two separations from and subsequent reunions with the parent. Using criteria identified by Ainsworth et al. (Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978), attachment behaviors, such as proximity seeking, contact maintenance, avoidance, and resistance, were coded when the child was reunited with his or her parent.

Children were classified as having a secure, avoidant, resistant, or disorganized attachment. Children received a secondary classification of disorganized attachment if they exhibited a lapse in their strategy in response to distress. Children classified as having a secure attachment seek contact with their parent during reunion episodes and are able to calm down during such reunions. Children classified as having an avoidant attachment do not look to the parent for reassurance or turn away during reunion episodes. Children classified as having a resistant attachment show a mixture of proximity seeking and resistance, combined with an inability to be soothed during reunion episodes. Finally, disorganized attachment is characterized by unusual behaviors, such as displays of contradictory behaviors, freezing or stilling, approaching the stranger when upset, expressing fear when the parent returns, and disoriented wandering (Main & Solomon, Reference Main and Solomon1990). These classifications were then collapsed into a two-way classification that was used in the current paper. Specifically, children were classified as organized (secure, avoidant, or resistant) or disorganized (disorganized-secure, disorganized-avoidant, or disorganized-resistant), as has been done in previous research (e.g., van Ijzendoorn et al., Reference van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel and Bakermans-Kranenburg1999). In some instances, children exhibit extreme behaviors that do not fit into the previously identified categories and are labeled “cannot classify.” In these instances, the cases were included with the cases classified as disorganized, as has been done in previous research (e.g., Lionetti, Pastore, & Barone, Reference Lionetti, Pastore and Barone2015).

Two coders, masked to intervention status, classified each participant's Strange Situation. The primary coder, who had previously attended Strange Situation coding training at the University of Minnesota and passed the reliability test, coded all videos. The second coder, an expert coder of Strange Situations and coleader of Strange Situation coder training, coded 32% of the videos. The two coders agreed on 89% of the four-way classifications of secure, avoidant, resistant, and disorganized/cannot classify (k = .75). In addition, the two coders agreed on 89% of the two-way organized-disorganized/cannot classify classifications (k = .77). For the purposes of data analysis, classifications assigned by the second coder were used for double-coded videos.

Atypical maternal behavior: AMBIANCE (Bronfman, Madigan, & Lyons-Ruth, Reference Bronfman, Madigan and Lyons-Ruth2009–2014)

Disrupted parenting behavior was coded from videos of the Strange Situation procedure. AMBIANCE yields several components of disrupted parental behavior including five separate dimensions of parental behavior, an overall level of disrupted communication, and a categorical indication of whether or not the parent is disrupted or not disrupted. The five dimensions, coded on 7-point scales, include affective communication errors (e.g., contradictory signaling to the child, failure to respond to infant cue, inappropriate response to infant cue), role/boundary confusion (e.g., prioritizing parent's needs over child's, treating infant as a sexual partner), fearful/disoriented behaviors (e.g., appearing frightened by the child, exhibiting disorientation), intrusiveness/negativity (e.g., physically harming the child, engaging in negative verbal comments toward the infant), and withdrawal (e.g., engaging in silent interactions with the child, directing infant toward toys rather than providing comfort during distress). Parents coded high on each dimension are likely to engage in more frequent and/or intense levels of the behavior, whereas parents coded low on each dimension are likely to engage in the behavior less frequently, as well as engage in less problematic forms of the behavior.

The first author, masked to intervention status and child attachment security, coded all Strange Situation videos. This coder was trained by the developers of the current AMBIANCE manual (E. Bronfman, S. Madigan, and K. Lyons-Ruth) and had successfully completed the reliability set of randomly selected videos (n = 25) that was used in the current project prior to coding the remaining videos. Twenty-nine videos (27.6%) were double coded by the second author, E. Bronfman, who is a developer, trainer, and expert coder of AMBIANCE. Interrater reliability was assessed using intraclass correlations and were as follows: affective communication errors, .80; role/boundary confusion, .73; fearful/disoriented behavior, .68; intrusive/negative behavior, .85; withdrawal, .74; and level of disrupted communication, .79. Disrupted classification agreement was 89.7%, k = .78 (p < .01). For the purposes of data analyses, scores coded by the second author were used for double-coded videos.

Data analyses

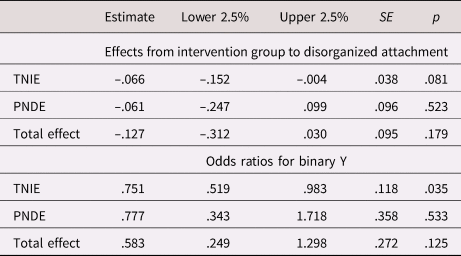

Descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, chi-square tests, and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were completed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 24.0). The remaining analyses were conducted using MPlus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017). Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to account for missing data in MPlus. Although full information maximum likelihood was specified in the model, the current analyses used data when both parent and child outcomes were able to be coded (i.e., the sample of 105 the current paper is reporting on), and therefore there were no missing data in the mediation analysis. A structural equation model with a dichotomous outcome (i.e., attachment disorganization) and a continuous mediator (i.e., withdrawal) was estimated based on guidelines described by Muthén and Asparouhov (Reference Muthén and Asparouhov2015) and Muthén, Muthén, and Asparouhov (Reference Muthén, Muthén and Asparouhov2016). This method allowed for the assessment of whether mediation occurred through the use of counterfactuals (i.e., what the value would be if the person were randomized to receive the alternative intervention). The total effect of the intervention is then broken down into the pure natural direct effect (PNDE; the effect of the intervention on the outcome that is not explained by the mediator) and the total natural indirect effect (TNIE; the effect of the intervention on the outcome that is explained by the mediator). The mediation model was fit using probit regression for the binary outcome and bootstrapping in order to obtain confidence intervals (CI). If the CI of the odds ratio (OR) does not include 1, then this can be interpreted as statistically significant.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Bivariate correlations and associations between variables

Child age at the initial postintervention visit was significantly negatively correlated with parental fearful/disoriented behavior (r = –.27, p = .01). Table 2 provides descriptive statistics and correlations between independent and dependent variables. We assessed whether child gender should be included as a covariate in our mediation analysis. Child gender was not significantly associated with parental withdrawal or disorganized attachment and was therefore not included as a covariate. Of note, bivariate correlations indicated that parental withdrawal was the only disrupted parenting behavior associated significantly with both intervention group and disorganized attachment quality.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations of study variables

Note: Intervention was coded 1 for participation in ABC and 0 for participation in DEF. Child disorganized attachment was coded 1 for disorganized attachment and 0 for organized attachment. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Parental disruption and child disorganization

Children whose parents were categorized as disrupted were more likely to be categorized as having a disorganized attachment than children whose parents were categorized as not disrupted (χ2 = 12.01, df = 1, p < .01). Specifically, 53.3% (n = 32) of children had a disorganized attachment when their parent was disrupted, whereas only 20.0% (n = 9) of children had a disorganized attachment when their parent was not disrupted.

Child disorganization

As noted earlier, Bernard et al. (Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012) previously reported data from the same RCT using a larger sample of participants (n = 120) than in the current study (n = 105). Forty-four percent (n = 53) were classified as having a disorganized attachment in the initial study. Further, the proportion of children classified as having a disorganized attachment in ABC (32%) was significantly smaller than the proportion of children in the DEF condition (57%).

Although not a primary aim of the current study, given that the intervention effects on attachment organization from the larger sample have already been reported (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012), we wanted to assess whether intervention effects on attachment disorganization were maintained in the current sample. Results indicate that 39.0% of children were classified as having a disorganized attachment at the first follow-up visit after completion of the intervention. A chi-square test revealed no significant difference between children whose parents received ABC versus DEF (χ2 = 1.99, df = 1, p = .16). Approximately 32.0% (n = 16) of children whose parents received ABC were classified as having a disorganized attachment, and 45.5% (n = 25) of children whose parents received DEF were classified as having a disorganized attachment.

Primary analyses

Aim 1. Intervention effects

Disrupted parental behavior

At the first follow-up visit after completion of the intervention, 57.1% (n = 60) of parents were categorized as disrupted. A chi-square test revealed no significant difference between parents who received ABC versus parents who received DEF (χ2 = 1.03, df = 1, p = .31). Approximately 52% (n = 26) of parents who received ABC were categorized as disrupted, and 61.8% (n = 34) of parents who received DEF were categorized as disrupted.

A significant effect of intervention on parental withdrawal was revealed F (1, 104) = 4.59, p = .03, such that parents who were randomized to receive ABC demonstrated significantly lower levels of withdrawal (M = 3.76, SD = 1.44) than parents who were randomized to receive DEF (M = 4.42, SD = 1.69). This represented a small to medium effect size (Cohen's d = – 0.42). No significant effects of intervention were found on affective communication errors, F (1, 104) = 0.96, p = .33, role/boundary confusion, F (1, 104) = 0.11, p = .74, fearful/disoriented, F (1, 104) = 0.41, p = .52, or intrusive/negativity, F (1, 104) = 0.28, p = .60.

Aim 2. Assessing a mediation model of intervention effects

Although we hypothesized that lower levels of fearful/disoriented behavior and withdrawal would mediate the association between intervention group and disorganized attachment, only parental withdrawal was correlated with both attachment quality and intervention group. Further, only parental withdrawal differed significantly between intervention groups. Therefore, we only assessed parental withdrawal as a mediator of change.

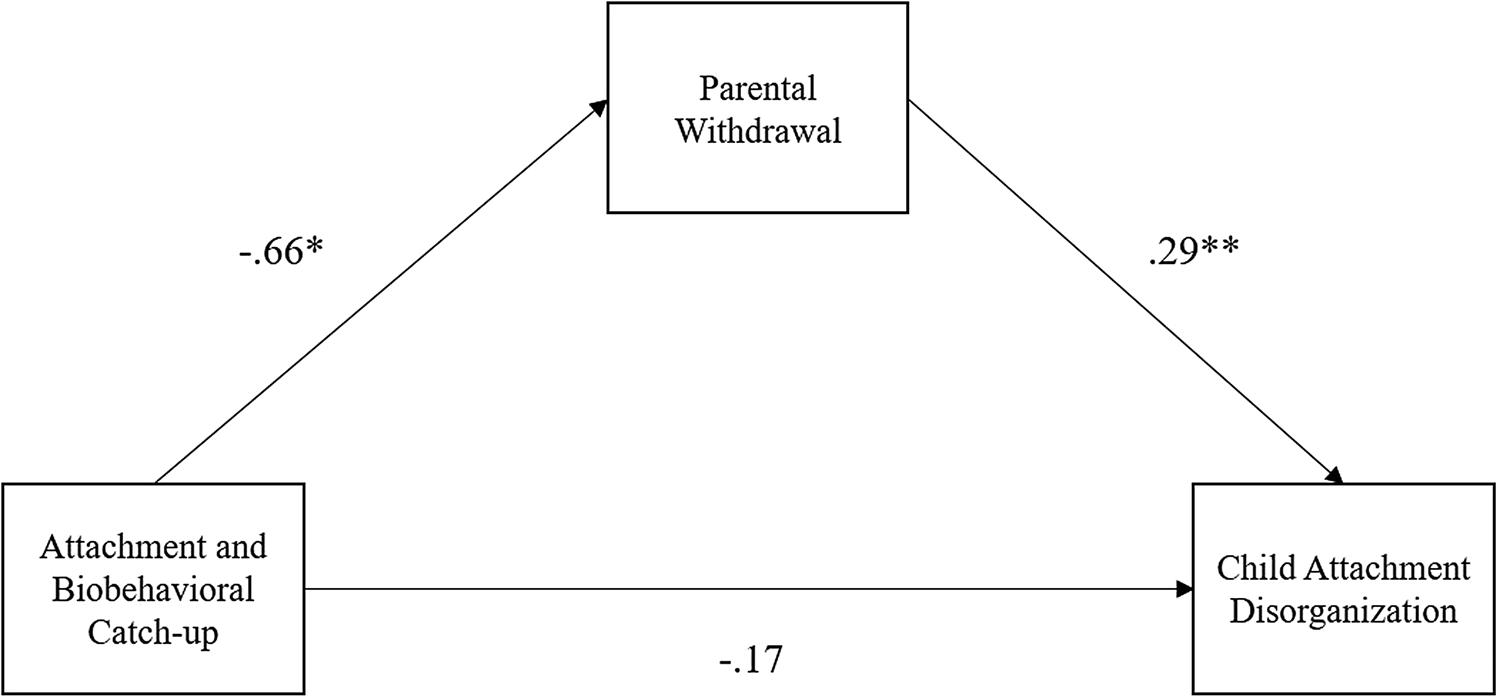

Mediation model

Results suggested that the ABC intervention led to lower odds of children showing attachment disorganization (OR = 0.58, 95% CI [0.25, 1.30]); however, consistent with results of chi-square tests earlier, the CI covered 1, and therefore, there was no significant total effect (i.e., the effect of intervention on the proportion of children classified with a disorganized attachment). The PNDE, or the effect of the intervention on the outcome that is not explained by the mediator, was also not significant. Results indicate that the TNIE, or the effect of the intervention on the outcome that is explained by the mediator, was significant. Specifically, the TNIE OR was estimated to be 0.75 (95% CI [0.52, 0.98]). Parents’ withdrawal at the postintervention assessment accounted for approximately 52% of the effect of ABC on the proportion of children classified as having a disorganized attachment, as indicated by the ratio of the indirect (–.066) to total effect (–.127) before being converted into odds ratios. See Table 3 for bootstrap CIs of total, indirect, and direct effects based on counterfactuals. Figure 1 provides a visual of the mediation model.

Figure 1. The positive effect of the Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up intervention on children's attachment quality through decreases in parental withdrawal. Standardized coefficients are shown. See Table 3 for tests of the indirect effect.

Table 3. Bootstrap confidence intervals for intervention effects on child disorganized attachment

Note: TNIE, total natural indirect effect. PNDE, pure natural direct effect.

Discussion

The current study evaluated the ABC intervention's efficacy in decreasing disrupted parenting behaviors through a RCT. In addition, the current study extended previous research by examining a hypothesized mediator (i.e., reductions in parental withdrawal) of intervention effects on child outcomes.

The first aim of the current study was to investigate whether parents who were randomized to receive the ABC intervention displayed less disrupted parenting behaviors after completion of the intervention than parents who were randomized to receive the control condition. Parents who received the ABC intervention demonstrated significantly less withdrawal at the first follow-up visit after completion of the intervention than parents who received DEF. ABC targets parental withdrawal through the intervention aims of following the child's lead and providing nurturance when children are distressed. Therefore, it is not surprising that parents who were randomized to receive ABC demonstrated lower rates of withdrawal than parents who received the control condition. For example, parents who engage in withdrawing behavior may have no interaction with their child during times of distress, put their child down too soon, or dismiss their child's need for comfort, all of which are antithetical to provision of nurturance when children are distressed or following children's leads.

No significant differences between parents randomized to receive the ABC intervention and the DEF intervention were found with regard to parents’ levels of affective communication errors, role/boundary confusion, fearful/disoriented, or intrusive/negativity. With regard to intrusive/negativity, previous RCTs investigating ABC's efficacy at changing parenting behavior have demonstrated that parents randomized to receive ABC displayed significantly less intrusive behavior than parents randomized to a control condition (e.g., Yarger et al., Reference Yarger, Hoye and Dozier2016). One explanation for the discrepancy between studies may be the different coding systems used. Previous studies assessing intrusive parenting behavior used an adapted version of the Observational Record of the Caregiving Environment (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1996) coding system that operationalizes intrusive parenting behavior more broadly than the AMBIANCE coding system's operationalization of intrusiveness/negativity. Further, the current study assessed parenting behavior during the reunion episodes of the Strange Situation, which is a time of heightened attachment stress, as compared to during free-play interactions. The lack of intervention effects on parental fearful/disoriented behavior was also unexpected, as one of the ABC intervention targets is decreasing parental frightening behavior. The base rates of fearful/disoriented behavior were quite low, therefore reducing statistical power. After creating a dichotomous variable to determine the percentage of parents coded as a 5 or higher on the fearful/disoriented scale, only 17.1% (n = 18) were considered to be within the “disrupted” range of the scale. Finally, the nonsignificant effects of the ABC intervention on role/boundary confusion may also be explained by the low base rate of parents demonstrating significant disruption within this dimension (i.e., coded as a 5 or higher on the scale). Post hoc transformations of the dimension into a dichotomous variable demonstrated that only 12.4% (n = 13) of parents were identified as within the “disrupted” range of role/boundary confusion.

The second aim was to investigate whether decreases in disrupted parenting (i.e., parental withdrawal) as evidenced by intervention effects mediated the association between intervention status and the proportion of children classified with disorganized attachment. Mediation analyses support the hypothesis that the ABC intervention led to a lower proportion of children classified as having a disorganized attachment by decreasing parental withdrawal. These findings contribute to our understanding of the developmental sequelae of disrupted parenting behavior, such that parental withdrawal in particular was identified as a risk factor for attachment disorganization. These findings are in line with research that points to parental withdrawal as a risk factor for dysregulation throughout the life span (e.g., Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bureau, Easterbrooks, Obsuth, Hennighausen and Vulliez-Coady2013).

Of note, this study provides evidence that ABC, a short-term attachment-based intervention, was effective at reducing parental withdrawal within a sample of parents who had substantiated or unsubstantiated reports of maltreatment such as abuse or neglect. In 2016, 676,000 children were identified as being victims of abuse or neglect, with neglect representing 74.8% of the cases (US Department of Health & Human Services, 2018), highlighting a need for interventions that target these behaviors. In a high-risk sample of families referred to the Expertise Center for Treatment and Assessment of Parenting and Psychiatry in the Netherlands due to concerns regarding parenting quality, none of the parents who ultimately received positive family preservation decisions were categorized in the disrupted range on parental withdrawal or fearful/disoriented behavior as coded by AMBIANCE (Vischer, Knorth, Grietens, & Post, Reference Vischer, Knorth, Grietens and Post2019). These findings highlight the importance of targeting parental withdrawal in high-risk families. Further, the ability to reduce parental withdrawal within 10 sessions is important given the difficulty of continued engagement of parents in parenting interventions, especially within high-risk populations, in community settings (Gonzalez, Morawska, & Haslam, Reference Gonzalez, Morawska and Haslam2018).

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

The current study had several strengths including assessing intervention effects within a RCT framework (e.g., the use of random assignment into the experimental or control condition), which provides increased confidence in the finding that the ABC intervention promoted reductions in parental withdrawal. The study also used observational methods of parenting behavior and child attachment quality, rather than self-report methods, which allowed for more objective assessments of the behavior being coded. Further, evaluating the mediation model using counterfactuals takes into account the odds that a child would be categorized as having a disorganized attachment with his or her parent if they would have been assigned to the alternative intervention.

Although there were several strengths, results of the study should be interpreted within the context of its limitations. As noted previously, the current sample is a smaller sample size than previously reported (i.e., Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012). The current sample included 83.8% (n = 89) of the sample reported in the Bernard et al. (Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012) paper. There are several reasons why there were differences between the two samples including difficulties with video quality, removal of siblings and fathers from the current sample, and additional families completing the intervention after publication of Bernard et al. (Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012). The difference in sample led to differences in attachment disorganization, which leaves questions as to whether the full sample size would reveal similar results. In addition, the current sample had low base rates of some of the dimensions of parenting behaviors that were coded (e.g., role/boundary confusion) and therefore that may have limited the ability to evaluate whether ABC is effective at reducing these parenting behaviors. Finally, the current study assessed disrupted parenting and child attachment quality simultaneously, which does not follow the requirement of time-ordered variables in mediation analysis (Tate, Reference Tate2015). However, conceptually, attachment quality in infancy develops from a history of interactions with a primary caregiver, and therefore following the Hyman–Tate conceptual timing criterion, one can infer that mediation occurred in the direction discussed. Future studies should continue to disentangle these relations through coding parenting behavior in a paradigm (e.g., parent–child play interaction) other than the Strange Situation.

In order to continue to understand consequences of disrupted parenting, future studies should continue to assess the unique contributions of each disrupted parenting behavior on children's social and emotional functioning. Further, studies should directly test the longitudinal impact the improved parenting behavior has on later developmental outcomes. In addition, investigating additional factors that may serve as risk (e.g., cumulative risk index or parental attachment representations) or protective factors (e.g., sensitive parenting) for the development of attachment quality and emotional and behavioral functioning later in life are important next steps.

In sum, we found that ABC, a brief attachment-based parenting intervention, was successful at reducing parental withdrawal, a behavior that has been shown to place children on a negative developmental trajectory through adulthood. Identifying interventions that can alter parenting behavior during a key developmental time period, and briefly, is crucial when implementing interventions in real-world settings. Finally, identifying parental withdrawal as the mediator of change from intervention group to decreased rates of disorganized attachment continues to point to the dysregulating affect parental withdrawing behavior can have on children's development and supports the need for interventions such as ABC that directly target disrupted parenting behavior.

Acknowledgments

We thank the children and families who participated in the research, and also gratefully acknowledge the support of child protection agencies. We also thank the doctoral committee (Tania Roth, Roger Kobak, Jean-Philippe Laurenceau, and Sheri Madigan), who provided constructive feedback on this project.

Financial Support

The project described was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 MH052135, R01MH074374, and R01MH084135 (to M.D.).

Author note

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This project was presented in a symposium at the 2019 biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development.