I

On Armistice Day, 1937, a Great War veteran spent the two-minute silence thinking about ‘a couple of pals who were blown to hell at Ypres, 1915’ and ‘how soon we should all be joining up again’.Footnote 1 The long shadow of the Great War and long foreshadowing of the Second World War had begun to overlap. Two years later, on 11 November 1939, the impending conscription of a customer's son was the topic of conversation in a Bolton fish shop: a fellow patron offered reassurance – ‘He'll be alright, you've nothing to worry about’ – to which she replied ‘Yes, but I won't be alright. I had enough last war – they took my husband then, now they want my two lads.’Footnote 2 By December 1939, one million people had joined the forces, including reservists and territorials.Footnote 3 One Great War veteran remarked that seeing young lads in uniform ‘made him go cold. They didn't know what they were in for.’Footnote 4 Most probably they would not have guessed they might still be in uniform in 1945. In late 1939, nearly a third of Britons polled by the British Institute of Public Opinion (BIPO) expected the war would be over by Christmas 1940. The same proportion, perhaps remembering that ‘over by Christmas’ had been a much mistaken refrain in 1914, expected it would be at least two years before the war was over.Footnote 5 Such speculation was all very well, but the response a fifty-five-year-old woman in Bolton gave when a man conducting street surveys for Mass Observation (MO) asked when she expected the war to end was in some respects more perceptive: ‘No idea; it hasn't started yet has it?’Footnote 6 The period from September 1939 to April 1940 was anti-climactic for most Britons, and earned the moniker the ‘Bore War’ or the American description, the ‘Phoney War’.Footnote 7 The war at sea was active as Britain attempted an economic blockade.Footnote 8 Yet by December 1939, the Royal Air Force had dropped only propaganda leaflets on German cities, and the British Expeditionary Force stood waiting at the Franco-Belgian border.Footnote 9 Civilians waited, too. Crucially, the much-anticipated bomber had not attempted to get through to British cities. Almost half of those who had been evacuated in September 1939 had returned home.Footnote 10 By February 1940, the combination of inactivity and what consequently seemed unnecessary restrictions to their daily lives, most notably the nightly rigmarole of the blackout, had created Britons who were frustrated by and bored with the war.Footnote 11

In February 1940, MO – a social research organization founded by left-leaning intellectuals, Tom Harrisson and Charles Madge in 1937 – was investigating how ‘ordinary people form their opinions on current events’.Footnote 12 MO aimed to allow ‘the masses to speak for themselves, to make their voices heard above the din created by the press and politicians speaking in their name’.Footnote 13 Among other methods of establishing public opinion, MO asked a ‘national panel’ of volunteers to respond to a monthly ‘directive’ – a set of questions that invited reflective answers, submitted by post. In February 1940, directive question eight asked: ‘How much do you think childhood impressions and incidents colour your opinions in the present war? And if you do think childhood does affect your present opinion, in what way do you feel these effects work?’Footnote 14 Neither MO nor scholars have analysed the responses. Most of the 239 respondents to the directive offered reflective explanations of what they thought influenced their current opinions about the war, whether from childhood or not.Footnote 15 As a result, the responses reveal much about respondents’ attitudes to the Second World War and what they perceived to have shaped them. They thus provide insight into the underexplored topic of morale during the Phoney War, and the findings presented here both confirm and qualify some of the concerns about low morale that MO expressed at the time. Significantly, like the reflections that opened this article, the directive responses also reveal something which was unobserved in the contemporary assessments of early war morale: memories of the Great War played a role in shaping some Britons’ attitudes to the Second World War. Analysis of the directive responses, and ‘chance mentions’ of the Great War within Britons’ conversations captured by MO, demonstrates that many Britons looked backwards to 1914–18 in late 1939 and early 1940, whether they had lived through the Great War or not, and a significant proportion considered the Great War to influence their attitude during the Phoney War. Memories of wartime trauma were just one facet of the varied legacy of the Great War that Britons drew upon. Importantly, the extent to which Britons drew upon and ascribed influence to personal experiences, vicarious memories, post-war representations, and commemorative rhetoric varied according to their age. This examination of how Britons used, or did not use, cultural representations of the Great War adds to our understandings of both the reception and influence of cultural representations of the Great War, and the place of the Great War in the subjective worlds of Britons during the Second World War. That individuals who could drew upon their personal experience rather than cultural representations complicates the historiographical assumption that cultural representations determined Britons’ responses to the outbreak of the Second World War. By examining both the memory of the Great War and morale during the Phoney War, and by locating one within the other, this article contributes to, and connects, these two distinct historiographies.

II

Scholars of the memory of the Great War have paid much attention to the cultural representations of the experience and meaning of the Great War in interwar Britain. An initial focus upon elite literature – including writing by Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, Wilfred Owen, and R. C. Sherriff – led to the suggestion that British society became disillusioned with warfare after 1918.Footnote 16 Historians have since highlighted that these authors were ambivalent about their wartime experiences, and that disillusioned narratives were contested at the time.Footnote 17 As historians have looked beyond the canon, they have seen a more nuanced picture. Between the wars, widely consumed media, such as juvenile fiction, middlebrow novels, and film, typically presented the war in traditional terms: redemptive sacrifice; heroic soldiering; and even within a pleasure culture of war as masculine adventure.Footnote 18 Although similarly contested sites of memory, commemorative ceremonies typically did not deny deaths meaning.Footnote 19 As Daniel Todman has argued, ‘Britons want[ed] to remember very different versions of the war. Although none completely obscured the horror and the suffering inflicted by the war, the meanings derived from those experiences varied widely.’Footnote 20

The suggestion that cultural representations of the Great War, particularly the canonical war books, shaped how Britons understood the Great War and therefore informed how Britons imagined and responded to the next war is implicit in some histories of the cultural memory of the Great War, and explicit in others.Footnote 21 Stephen Heathorn was, however, right to insist that to know whether these representations shaped the thinking of ordinary people we must look ‘beyond the intentions of artists and intellectuals to look at how the conflict's representation has been received and understood by the population at large’.Footnote 22 Understanding the significance of both experiential and cultural memories of the Great War to ‘ordinary’ Britons is key to understanding the Great War's legacy. Yet, as Martin Francis recently highlighted, historians have been slow to examine ‘the legacy of the First World War on the subjective worlds of participants in the Second’.Footnote 23 Recent scholarship has begun to address this. Historians have shown that the memory of the Great War affected the thinking of politicians and generals leading the British war effort,Footnote 24 and the attitudes and behaviour of servicemen enlisted to fight it.Footnote 25 Civilians facing the Second World War were affected, too. Susan Grayzel has connected Britons’ understandings of air raids in the 1930s and 1940s with air raids during the Great War, Jessica Hammet has examined how Great War veterans’ experience of serving in Civil Defence in the Second World War was affected by their veteran status, and Francis has illustrated that some Britons were unable, or unwilling, to ‘minimize the trauma of the First World War to surmount the challenges of the Second World War’.Footnote 26 Lucy Noakes has explored the place of Armistice Day in the subjective worlds of Britons between 1937 and 1941, showing that, although Britons were sensitive to others’ trauma, their diverse personal responses demonstrate a ‘profound lack of consensus around the meanings of Armistice Day’.Footnote 27 Noakes's study illustrates how the coming of the Second World War shaped attitudes to remembering the Great War. This article does the reverse; it examines how both experiential memories and cultural representations of the Great War shaped everyday Britons’ attitudes to the Second World War during its early months. It contributes to efforts to assess the influence that components of the cultural memory of the Great War had on ordinary Britons and to locate the legacy of the Great War in the subjective worlds of Second World War participants. It shows that many Britons shared the assumption that the Great War was the inevitable reference point early in the Second World War; demonstrates the common, but far from universal, significance that people of different generations accorded to the Great War in relation to their opinions on the current war; and reveals that Britons of different ages drew upon different types of memory and representation of the Great War when forming their attitudes to the Second World War. The rhetoric of the Great War's commemorative legacy informed, and was used to articulate, feelings of disappointment, and even betrayal, when ‘The “Last War” became the last war’.Footnote 28 Nevertheless, that respondents typically ascribed influence to experience rather than cultural representation, where they could, complicates the assumption that cultural representations of the Great War, and especially elite literature, were the dominant influences upon Britons’ understandings of the last war or responses to the next war.

Examining how the legacy of the Great War shaped Britons’ attitudes to the Second World War during the Phoney War also illuminates how Britons felt about the war itself. Morale in the early war has received little scholarly attention. Britons’ responses to the Blitz have proved a more popular target.Footnote 29 Even Robert Mackay's study of civilian morale devotes little discussion to the Bore War, and those examining this period often focus on evacuation rather than wider attitudes to the war.Footnote 30 MO, however, had much to say on the subject in their published wartime analyses and unpublished File Reports. Informed by these, Mackay and others have suggested that the British public had become bored, frustrated, and apathetic.Footnote 31

In War begins at home, published in January 1940, MO expressed concern about low morale and complained that the government's misunderstanding of public attitudes could jeopardize the war effort: because the government assumed that ‘the Home Front is at least as strong as the Maginot Line’ they had neglected to sell the war to the people – it had not yet become ‘everyone's war’.Footnote 32 This mirrored the sentiment of a Picture Post illustration in November 1939 which satirized the state's exclusion of the people by depicting a sign reading: ‘“Keep Out! This is a private war. The War Office, the Admiralty, the Air Ministry and the Ministry of Information are engaged in a war against the Nazis. They are on no account to be disturbed.”’Footnote 33 Harrisson and Madge contended that ‘the Government should be fully aware of all the trends in civilian morale. They needed an accurate machine for measuring such trends; a war barometer’, which – not coincidentally – MO could provide.Footnote 34 Morale was difficult to define; MO considered it ‘the amount of interest people take in the war, how worthwhile they feel it is’, and both MO and the state focused on how Britons felt about the war, taking complaints and ‘grousing’ about wartime experience as indicators of low morale.Footnote 35 In early 1940, Harrisson claimed the British public, unsure of Britain's war aims due to inadequate government communication, had adopted ‘Defendism’: they were not defeatist, but lacked ‘fire and fury’.Footnote 36 Harrisson predicted this would shift when the masses experienced ‘a violent hook which will force them to face up to the issues of this war and the improbability of an “easy victory”’.Footnote 37 Yet, so long as the war resembled peace, individuals could continue to appease their internal conflicts. As Kingsley Martin, editor of the New Statesman, wrote in early 1940:

The most important single fact in the psychology of the public during recent years has been the co-existence of several ‘opinions’ at the same time in almost everyone; we have all been conscious of having within us a tendency to isolationism and pacifism, as well as to bellicosity, righteous indignation and the urge to set the world right … In the past it has been true that once war has started, such emotional conflicts are promptly settled.

But without a clear sense that war had started, this ‘hardening process’ had been delayed.Footnote 38 Although MO and BIPO both observed that Britons were united in a desire to end the Hitler regime, MO worried that far from being committed, ‘ordinary people … have not faced up to or begun to realise the tremendous demands, the almost intolerable strain, which active prosecution of this war will call for’.Footnote 39 They likened some Britons to ostriches, burying their heads in the sand,Footnote 40 and said that many (particularly working-class women), ‘have been wishfully thinking [war] away’.Footnote 41 In February 1940, based on people leaving their gas masks at home and careless blackout observation, MO suggested the public had become apathetic.Footnote 42 Alongside the boredom and desire to ‘get on with the war’, MO identified a proportion of the public who ‘felt it isn't worth anybody being bombed for any reason whatever’. They predicted the division between ‘“get on with the war” and “stop the war” is likely to grow’.Footnote 43 BIPO polls suggest a different picture. February 1940's poll identified perhaps 10 per cent who favoured stopping the war but most Britons still supported continuing the war to get rid of Hitler.Footnote 44 The 29 per cent who would approve of peace talks was nearly double that of September 1939, but only half as many as would disapprove.Footnote 45 Approval fell to 25 per cent in March.Footnote 46 Based on analysis of BIPO polls, police reports to the Ministry of Information (MOI), and twenty-two people's responses to an MO ‘Working Class War Questionnaire’ conducted in November 1939, Todman suggests that MO's interpretation made morale appear more fragile than it was and offered a pessimistic assessment of its trajectory.Footnote 47 MO's File Reports and publications were sometimes impressionistic, and were perhaps even opportunistic at this point; struggling financially and hoping to be commissioned to study morale for the MOI, MO had reason to depict morale as unstable and in need of constant assessment. As Todman observes, War begins at home was ‘not only a report on findings; it was also a job application’.Footnote 48

This article examines attitudes and morale in the early war using a significant body of MO's verbatim material, which is more reliable than MO's reports and richer than opinion polls. It confirms that some Britons’ attitudes reflected the Bore War mood described above; individuals expressed impatience and a paradoxical wish for excitement, frustrations, wishful thinking, and deep regret that war had not been avoided. Many were, as Martin suggested, engaged in an internal conflict and were only gradually accepting (or even still trying to deny) that war had indeed begun. The state had not convinced everyone that this was ‘their war’, and Harrisson's description of ‘Defendism’ accurately described the feelings of many. This research also, however, supports the suggestion that MO were unduly pessimistic. Rather than apathy, Britons had typically regretfully resigned themselves to a war they had not wanted to protect what they (or even what others) already had. People did ‘wishfully think [the war] away’, but this was as much because they had ‘begun to realise … the almost intolerable strain which active prosecution of this war will call for’. By locating the memory of the Great War within attitudes during the Phoney War, this article shows that many Britons faced the Second World War with dismay because they looked back to their personal experiences or cultural representations of the Great War.

III

Gregory has suggested that to understand how the Great War has been remembered it is imperative to ‘get as close to the ground as possible’, and the same is true when examining morale.Footnote 49 MO produced a wealth of material that can be used to illuminate Britons’ subjective experiences, thoughts, and feelings during the Second World War. Full-time Mass Observers conducted street surveys and surreptitiously recorded the behaviour and conversations of members of the public.Footnote 50 I have scoured this kind of material, including most of that gathered as part of the Worktown project in Bolton, for ‘chance mentions’ of the Great War in conversations about the Second World War, particularly those of working-class Britons. The mass of MO's material, however, came from people who had volunteered to be part of their national panel. Some submitted wartime diaries, which have proved a useful source for scholarly analysis, but panellists’ responses to the monthly directive questions are also a very valuable source.Footnote 51 The questions were open to interpretation, as MO recognized, but, unlike opinion polls, panellists’ qualitative responses preserve their interpretations for analysis.Footnote 52 As will be shown, that many respondents interpreted question eight of the February 1940 directive in the same way is revealing. MO considered the directives the most likely method of accessing individuals’ private opinions because respondents ‘know we respect their confidence and anonymity, and are therefore prepared to give us the most detailed, candid, personal reactions’.Footnote 53 Some were certainly candid; for example, an eighteen-year-old student asked his opinion on the blackout wrote: ‘Personally, I like the Blackout; to walk in the dark exercises the mind, star-gazing is easier, and sex more sexy.’Footnote 54

MO was less candid about the national panel. The cover of Britain (1939) claimed a panel of 2,000 volunteer observers, a number – not coincidentally – comparable to the BBC listener research panel and the smallest BIPO samples.Footnote 55 This obfuscated panellists’ commitment. By the end of 1939, a total of 1,921 people had replied to a directive since MO's formation in 1937, but only 1,071 had in 1939.Footnote 56 No directive garnered more than 500 responses.Footnote 57 Over the course of the war, only around 300 respondents contributed consistently;Footnote 58 62 per cent of respondents replied only once.Footnote 59 That the panel was, in reality, an ever-changing body is of greater consequence than its limited size.Footnote 60 It has implications for longitudinal studies that have received insufficient acknowledgement. For example, in his study of shifting middle-class identity, Mike Savage makes too little of the fact that he is not sampling a static group's changing views over time but examining the responses of different groups of individuals at different times.Footnote 61 It also has implications for how scholars approach understanding whose views the national panel presents. The Mass Observation Archive undeniably ‘provides a unique opportunity to interrogate the ideas and feelings of large numbers of ordinary men and women’ and ‘offers an unparalleled insight into the subjective experiences of some of the British people, providing glimpses of “private”, emotional lives, and responses to public events, unavailable from more traditional, quantitative, sources’.Footnote 62 MO conceived of the panellists as more articulate and observant than the masses, though, and stressed that the national panel was intended to reveal the ‘why’ of public opinion rather than to be strictly representative of Britons.Footnote 63 Historians’ studies of the panellists, and the MO diarists amongst them, confirm that they were not representative. Hinton suggests the panellists perceived themselves as ‘a group of self-consciously enlightened individuals’.Footnote 64 They were probably better educated than average: the diarists had commonly attended grammar school, and read widely, though most were not graduates. They were typically politically left-leaning.Footnote 65 Panellists were also unusual in that they volunteered to share their opinions, though why they did so is difficult to establish.Footnote 66 Historians have also used Nick Stanley's finding that the collective panellists between 1937 and 1945 were unrepresentative of Britain's population in demographic terms.Footnote 67 Men, people from south-east and south-west England, and those aged 19–34 were heavily over-represented, while men over 35 and women over 55 were under-represented.Footnote 68 Scholars have responded to this in numerous convincing ways. Tony Kushner has highlighted that women and, to a lesser extent, the working classes, and individuals from nearly all geographic regions, wrote to MO, albeit not in representative ratios.Footnote 69 Some have extracted groups from the panellists (and particularly the diarists), as Alun Howkins has done to investigate rural experiences of the Second World War, and as Langhamer and others have done with women.Footnote 70 Others have argued that views on the topics under examination were unaffected by characteristics such as age, gender, and class, or that representativeness is not fundamental to their work.Footnote 71 Moreover, it is clear that historians can interpret material with an awareness of its inherent biases; as Calder remarked of the directive on race, although the panel was not representative, ‘if one knows how the Panel was composed, then the results in part seem highly significant’.Footnote 72 Both Kushner's and Calder's responses apply when interrogating the responses to the February 1940 directive. Nevertheless, the ever-changing nature of the panel has another implication that has not been emphasized in existing studies: because panellists’ participation was so inconsistent, the characteristics of the collective national panel between 1937 and 1945 are potentially an inaccurate guide to the characteristics of the respondents to any given directive. Therefore, when characteristics like age, gender, and class are important, an additional step in the research process is beneficial. Here, rather than relying upon data about the collective panel, the demographic characteristics of the 239 respondents to question eight of the February 1940 directive have been established. Like the panel, the February respondents over-represented men, people aged 19–34 (especially men), and the English, and they commonly, though far from exclusively, had lower-middle-class or middle-class occupations.Footnote 73 In relation to age and sex, however, data about the collective panel would have been misleading. The male February respondents were slightly older than the panel averages,Footnote 74 and the female February respondents were less varied in age than the female panellists; almost half of the women who responded to the February 1940 directive were aged 25–34, but only one third of the female collective panellists were in this age bracket.Footnote 75 The ratio of male to female February respondents in each age group was also different to the panel. These variations mean that reliance upon the panel data could have resulted in differences in their responses being attributed to gender when they might, in fact, be accounted for by age.

IV

Understanding the age of the respondents to question eight of the February 1940 directive is essential because the question asked about the influence of childhood, yet almost two-thirds of the respondents referred to the Great War and a third cited it as influential. Those who considered childhood impressions influential typically referred to the Great War,Footnote 76 but too few of the respondents’ childhoods had intersected with the Great War for this alone to explain its presence in the responses. A fifth of respondents were born after the Armistice, and nearly half – young adults by 1940 – had been younger than six years old in 1918. Of the male respondents, 15 per cent had been of service age during the Great War and, if veterans were not disproportionately keen to write to MO, perhaps as many as 7 per cent of the male respondents might be expected to have served.Footnote 77 The importance and validity of considering respondents’ answers in relation to the Great War is indicated by the work that many respondents did in their answers to position themselves in relation to the Great War; 15 per cent of the respondents explained that they were either ‘too old’ or ‘too young’ for their childhood to influence their current impressions because it had not intersected with the Great War, and they believed or assumed that understanding the last war was integral to one's opinions on the present war. Those who positioned themselves as ‘too old’ felt their experience of the Great War had eclipsed their childhood impressions and redefined their understanding of war. A forty-six-year-old man, a leather manufacturer from Market Harborourgh, replied ‘My opinion of the present war is entirely coloured by my experiences in the last war. I am sure my childhood had no affect whatever [sic] on my present views.’Footnote 78 Such ideas were mirrored in the response of a forty-two-year-old woman, a social worker from Chiswick, who felt her childhood ‘so remote as to have little bearing upon the world of today! … My impressions of the last war (which took place in my late teens) however, do seem to colour my ideas about the present war considerably.’Footnote 79 Those who positioned themselves as ‘too young’ assumed one would have looked to the Great War, but felt unable to do so, and implicitly discounted the influence of post-war impressions. An eighteen-year-old student draughtsman wrote ‘I'm too young to have known the last war, so childhood memories can't affect me in this one.’Footnote 80 The same assumption was inherent in the replies of a number of respondents who stated that they could not answer the question as it was obviously intended for those who had been children during the Great War.Footnote 81 That some interpreted MO's much broader question so narrowly demonstrates the strength of respondents’ expectation that people's opinions about the Second World War in 1940 were shaped by the Great War.

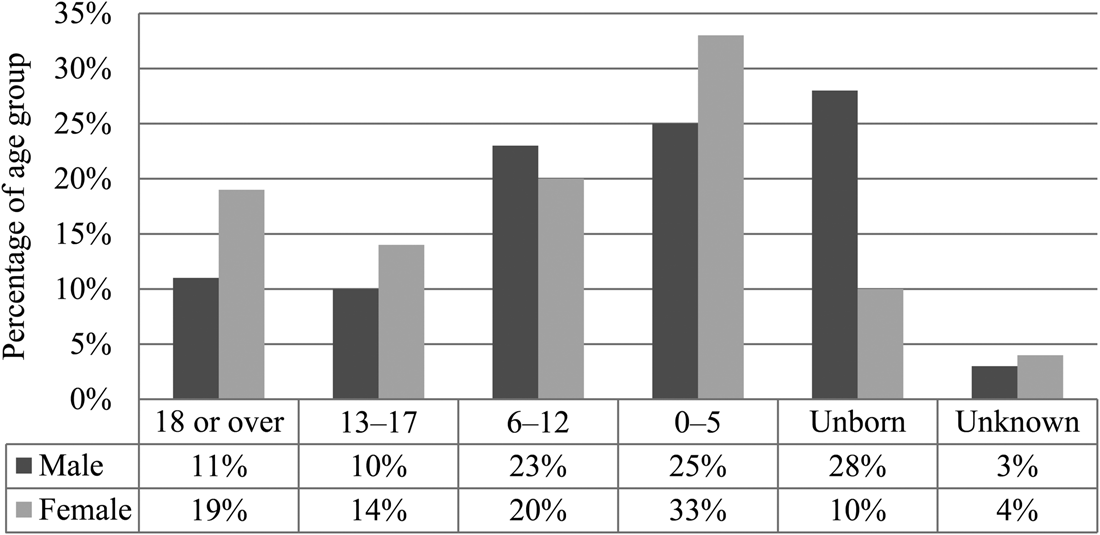

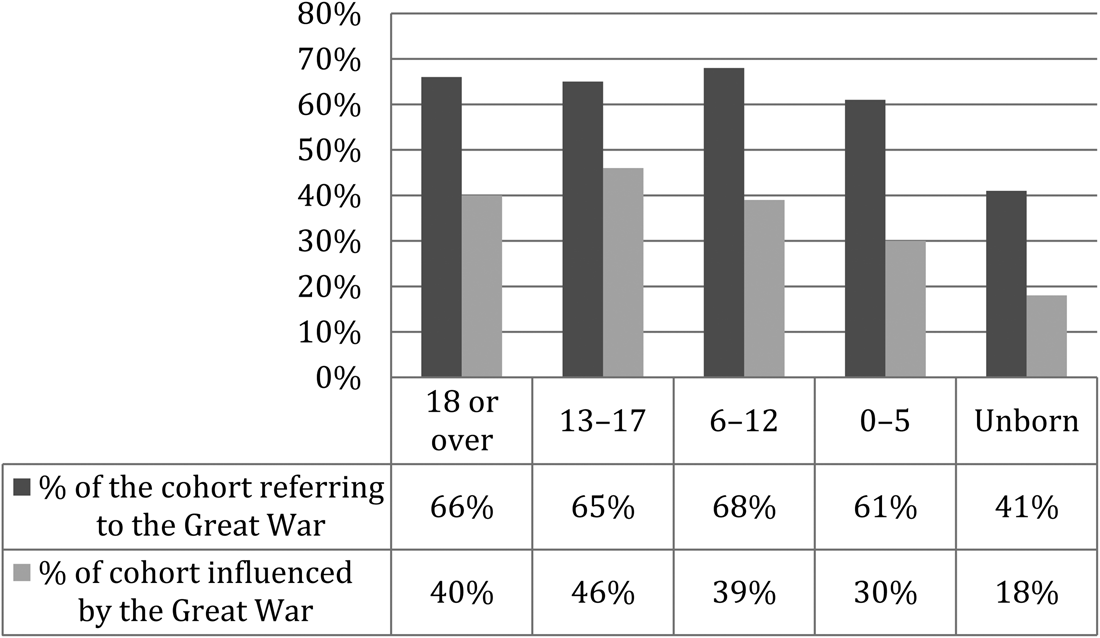

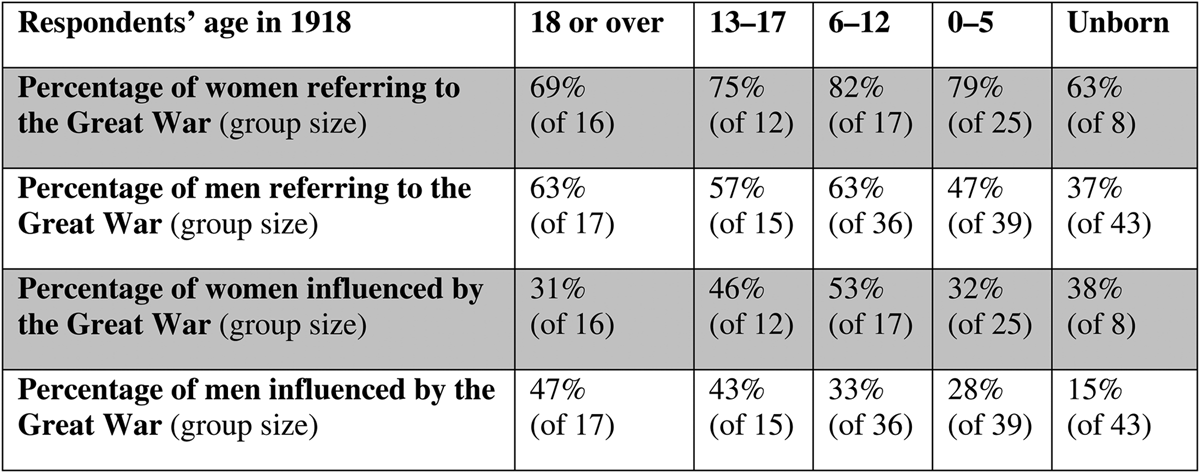

The temporal distance of the Great War by 1940 is striking when the respondents, who were all adults by 1940, are grouped according to their age in 1918 (Figure 1). The oldest of these experiential cohorts had reached at least service age by 1918, while the youngest was born after the war's conclusion. The cohorts in-between approximately separate those who could have memories of the Great War from those who might be expected to remember the Great War and those who were potentially of working age by the end of the Great War. Plotting references to the Great War and its influence on opinions in 1940 by cohort highlights the extent to which Britons were looking back to the Great War (Figure 2). It was referred to by more than half of those who had been babies, children, adolescents, or adults during the Great War, and considered influential by significant minorities of each of those groups. It was even considered influential by a fifth of those born after the Armistice. The respondents’ demographic composition means comparison of men's and women's responses by age cohort is statistically imperfect; the small number of female respondents born after the Armistice and the unequal number of men and women in that cohort make comparison problematic. The overall trends are, however, suggestive (Figure 3).Footnote 82 With the notable exception of men who were aged eighteen or over in 1918, women referred to the Great War much more commonly than their male counterparts, and, while the difference is much less consistent, women more commonly cited it as influential than men of the same age, too. It is plausible that personal memories and childhood experiences of rationing and Home Front difficulties had greater resonance with women's concerns in 1940 than with those anticipated by men, including military service. For instance, two women welcomed the prompt implementation of rationing, which started in January 1940, because they recalled food shortages during the Great War.Footnote 83 Moreover, young girls may have been more aware of the daily impact of the Great War on the Home Front as a result of greater involvement in domestic tasks. Another, not mutually exclusive, explanation is that respondents’ replies and self-perceptions are themselves gendered; more men responded that their current opinions were ‘reasoned’, informed by knowledge gained as an adult, including by reading, rather than childhood impressions.Footnote 84 Given the education and reading habits that Jeffrey observed amongst MO diarists, this perception may have been more common among MO respondents than Britons as a whole.Footnote 85 These gendered differences merit further investigation that cannot be provided here.Footnote 86 Nevertheless, the prevalence of references to the Great War in the responses of men and women of all ages shows that the Great War had a powerful legacy, and that it shaped the thinking of not only those who had had lived through it as adults but also those who had grown up in interwar Britain.

Fig. 1 Respondents’ age in 1918

Fig. 2 References to, and the influence of, the Great War by respondents’ age in 1918

Fig. 3 Differences in Great War references by gender and age

V

What Britons drew upon when they thought about the Great War in 1940 was shaped by age; personal memories, others’ post-war narrations, and representations within popular culture were referenced and cited as influential to differing degrees by those of different ages. Almost all those of service age in 1918 who referred to the Great War stated that it influenced their attitude to the Second World War. They recounted personal memories of the Great War, an experience that they considered to have eclipsed their childhood impressions. The character of their replies is captured in the response of a forty-eight-year-old park keeper from Eltham, London. He supported the Second World War, so long as it was confined to removing Nazism, but contrasted his attitude in 1940 to his militaristic boyhood enthusiasm during the Boer War, when ‘War was an enviable occupation, how we worshipped those men in their biscuit-khaki … Having lived through the 1914–1918 war all illusions vanished, of course.’Footnote 87 Women perceived the Great War to have removed illusions, too: a forty-two-year-old music teacher in Rotherham, who had delighted at the outbreak of the Great War,

soon became aware of the reality of war and I became sadder and a little wiser. Nevertheless I believed it was a war to end war, and anxious to do my bit, I joined the Women's Legion as a motor driver. Now I am still sadder though no wiser; only more disillusioned, more sceptical, more cynical.Footnote 88

Great War ‘Adolescents’, who had been aged 13–17 in 1918, drew upon their own memories of the war on the Home Front – wartime food, seeing wounded soldiers, and air raids – and for some, memories of the war's effect on them co-existed with memories of how the war had affected others: older school acquaintances had died; one remembered his mother's worry while his father served; and another remembered the ‘agony on those days when my father had to return to France after leave’.Footnote 89 The combination of personal memories and post-war narrations might have enabled adolescents to construct a picture of both the Home and Battle Fronts; one remembered ‘having to go without food to a certain extent, and seeing wounded Tommies and so on. I was working with some of them after the last war, and heard some first-hand tales.’Footnote 90 In terms of influences on their attitudes to the present war, ‘Adolescent’ women commonly cited a resultant fear of air raids, or the sense that this war does not seem so bad by comparison.Footnote 91 Male ‘Adolescents’ wrote less of fears and more of pacifist beliefs connected to impressions of the Great War. A businessman from Plymouth, who had been thirteen in 1914, explained that his ‘later reading affected me much more than childhood. The romanticism of war as seen by a child has been obliterated by intellectual approaches, the poetry of Sassoon and Owen etc.’Footnote 92 He was the oldest respondent to reference a post-war representation in popular culture. ‘Adolescents’ also commonly worried they could be easily reverted to their 1914–18 opinion that Germans ‘were a bad lot in every way … Now that war has come again and the same old type of story is being revived, one's mind is dangerously receptive.’Footnote 93

For those aged 6–12 in 1918, who had been ‘Children’ during the Great War, personal memories of the Great War varied from the concrete to the ethereal. For some, it was experienced at too great a temporal distance to leave influential impressions.Footnote 94 For others, geography and a lack of familial involvement kept war distant from their domestic sphere, meaning it had little influence even though they could recollect the war period.Footnote 95 ‘Children’ drew upon personal memories and assigned influence to them, but such memories tended to be of the Home Front, including food shortages and air raids, which even those with only vague memories connected to their sense of the useless destruction of war.Footnote 96 A small number of ‘Children’, though, remembered the Great War as a period of excitement, and felt either that the Second World War was boring as a result, or that greater enthusiasm was needed by the nation.Footnote 97 Like ‘Adolescents’, ‘Children’ discussed childhood impressions of Germans as ‘swine’, and some similarly feared that their enlightened adult perspective might be quickly reversed by atrocity stories.Footnote 98 Although one ‘Child’ felt the Great War caused his desire to join the forces, the ‘Children’ tended to see it as causing them to dislike and fear war.Footnote 99 ‘Children’, to a greater extent than ‘Adolescents’, drew upon their vicarious experiences of the First World War to explain their dismay at the outbreak of the Second; one pointed to the fact the Great War had ruined his father's business,Footnote 100 and others recollected the hurt experienced by family and friends upon receiving news of deaths in France.Footnote 101

Only the eldest of the Great War ‘Babies’, who had been five or younger in 1918, referenced personal memories of the Great War, and these were of Home Front events rather than awareness of broader context. Three stated they were too young to remember it.Footnote 102 Two suggested that they had simply accepted war as normal as it had been a feature of their lives for as long as they had been cognisant; one even felt at home now war had returned.Footnote 103 Some ‘Babies’ had clear recollections of witnessing events late in the war including air raids, the destruction of two zeppelins,Footnote 104 and the distress of women upon hearing of their husbands’ deaths,Footnote 105 but their personal memories tended to be vague, or had been reinforced after the fact. One particularly reflective respondent, born in 1914, acknowledged the uncertainty of his wartime recollections of a ‘permanent searchlight stationed at the end of the road … I was taken to the window to see it (Whether I actually remember this I don't know. More probably the story was repeated to me so many times that I began to think that I actually remembered it).’Footnote 106 Grayzel has noted that Great War air raids became central to civilian war experience, and expanded the battlefront into the Home Front.Footnote 107 These recollections of air raids make clear that air raids also expanded the generational impact of the Great War, with even the very young able to connect their experience directly to the conflict. Others who could not remember the war themselves based their impressions on what they had heard; one aged twenty-six in 1940 wrote ‘Heard of all the terrible things that happened between 14 to 18 and wished I had been born a few years earlier, so that I could have seen and experienced them myself. I was four and a half when the war ended.’Footnote 108 With the ‘Babies’, the Great War passed from lived to learned experience. Parental attitudes and an upbringing in an environment of ‘never again’ were emphasized, and post-war narratives became more important. One respondent, aged five in 1918, wrote that ‘Most of my impressions of the last war have been gleaned in later years from newspapers and old soldiers talking.’Footnote 109 What young people heard from veterans inside and outside their families varied significantly; veterans tended to emphasize rewarding elements of their service, but their narratives were, of course, dependent upon their experience.Footnote 110 For instance, disabled veterans’ children could be all too aware of the Great War's continued cost to their families.Footnote 111 Some respondents drew upon post-war representations that resulted from familial Great War involvement; one respondent learned that ‘the war’ was the cause of his brother's alcoholism, and the veteran brother of another respondent had remarked, in September 1939, that he would ‘stand shooting rather than go again’.Footnote 112 Familial narratives of wartime experience might be repeated, of course. A twenty-one-year-old student remembered boys at school between 1921 and 1926 talking about ‘how their uncles were killed (or how the boys imagined they were). Generally it was the uncle who was killed. Others had stories of what their fathers and their uncles did in the war – of how they captured Germans and escaped being hit by shells.’Footnote 113 Although this student feared that the Second World War could lead to another cycle of ‘poverty’, ‘unrest’, and future war, the way in which the stories are described suggests that, when narrated on the playground, they shared the tone of the ‘pleasure culture’ of war common in popular literature for boys in interwar Britain.Footnote 114 Such literature may well have been what a medical officer at the Liverpool Sanatorium was referring to when he explained that childhood literature and Armistice services were the origins of his sense of patriotic duty and his desire to join the forces in the Second World War.Footnote 115 The only other ‘Baby’ to reference post-war representations in popular culture cited an opposite impact, however. The response of a twenty-six-year-old from London, who listed her profession as ‘reader’, contained references to vague personal memories, and memories of the war's effect on others, but suggests the possibility that these could be bolstered by post-war representations. She felt her childhood impressions, particularly of seeing wounded soldiers, had a profound effect, and remembered ‘a general feeling of misery and unhappiness in those around me’ but remembered

very well the spate of war novels of the 1920s and early 1930s. I read these books avidly, I suppose because I had to fill in the facts about the war of which I had such vivid though such vague childhood impressions. I remember the bitterness and disillusion of those war books and I shared it.

In 1940, with some of those gaps filled, she could not understand people ‘glibly swallowing’ the same battle cries as last time, and found she had reactions of ‘horror and dread’ on seeing soldiers in uniform: ‘“Its happening again” I say to myself and feel sick. All this in spite of the fact that I nevertheless share the prevailing boredom about this war.’Footnote 116 This response not only illustrates the paradoxical emotions some Britons experienced, but also gives voice to Janet Watson's suggestion that one of the reasons that the war books were of such interest to the interwar generation was because they had missed out on the experience and needed to fill in the gaps.Footnote 117

Those who had been born after the Great War but saw it as influential had little option but to cite post-war representations from family and in popular culture. Parental attitudes to the Great War, particularly the transmission of the idea of the Great War as the ‘war to end all wars’ (which is discussed in the next section), were seen as influencing attitudes to the Second World War. One respondent recalled her mother ‘hated to talk of the war or listen to any radio programmes about it’, and her uncle told her ‘such ghastly stories’ that she shared her mother's fear.Footnote 118 Another, though, lived with his three veteran uncles who would not speak of their experiences; as a result he felt ‘while one half of my mind is aware of the horror and waste and above all the foulness of war, the other is prey to what I can only call a sadistic curiosity about the whole thing’.Footnote 119 Post-Armistice babies found contrasting impressions and varied influences in popular culture. A music student from Bexhill-on-Sea, born in 1919, was ‘just too late for the last war’, but as a child ‘looked through the pictorial history of the 1914–18 war frequently’, read the ‘usual “glorious” war stories in books and magazines’, and participated in war-play ‘starting with toys, graduating to mock open-air battles with old rifles, sticks etc.’ and subsequently joined the Air Training Corps.Footnote 120 Yet, another respondent cited a pictorial history of the war and War Illustrated as demonstrating the horrors of war.Footnote 121 That such conflicting influences could be ascribed to similar material illustrates the complexity of understanding the reception and influence of cultural representations. Like the Plymothian businessman, aged thirteen in 1914, who had been disillusioned by Sassoon and Owen, and the London reader born in 1914, who had used the war books to consolidate her vague childhood impressions, a clerk, born in the Midlands in 1922, perceived the origins of his dread of war to be seeing ‘“All Quiet on the Western Front” when I was about 10. I remember I was petrified with horror and disgust as I was later when I read the novel. I was and am a voracious reader and if anything influenced my youthful impressions it was books of all descriptions.’Footnote 122 Yet, that only three of the respondents to this directive – all quoted – made reference to ‘disillusioned’ cultural texts like All quiet and the work of Sassoon is notable, particularly as panellists were often well educated and well read in comparison to their compatriots. While the decade that passed between the end of the war and the start of the war books boom placed their publication outside the childhoods of many of the respondents, the responses as a whole illustrate that many respondents were prepared to step outside the confines of the directive question in order to communicate what they perceived to inform their views. These findings suggest that Vincent Trott was right to observe that those young readers who reported that their pacifism was fostered by reading Vera Brittain's Testament of youth (1933) were not necessarily typical of their generation.Footnote 123 That MO's respondents were drawing upon representations of the Great War from a wider range than the canonical disillusioned texts underlines the importance of the widening scope of the cultural history of the Great War in interwar Britain, just as critics of Paul Fussell have argued.Footnote 124 The responses also, however, demonstrate the need to look beyond cultural representations themselves; it was the younger respondents who most commonly referred to post-war cultural representations, which suggests that when personal memories or familial or second-hand experience could be drawn upon, representations of war in popular culture were less influential or were less readily perceived as such.

VI

Many of the responses to the February 1940 directive not only articulate respondents’ memories of the Great War but also explain the influence respondents perceived these memories to exert in 1940. These, and MO's survey and ‘overheard’ material, shed further light on how respondents felt the Great War shaped their thoughts and feelings about the Second World War.

One prominent theme was that individuals’ Great War experiences affected their fears of air raids. Air raids had been a dramatic and highly visible Great War experience, and were expected to be a prominent feature in the Second World War, enabling individuals to make a direct connection between their experience of one conflict and their response to another.Footnote 125 Grayzel has shown that some Londoners drew on their experiences of the Great War as they tried to make sense of the London Blitz.Footnote 126 These directive responses demonstrate Great War memories were shaping some Britons’ morale even as they anticipated Second World War bombing. A housewife, born in 1913, recalled ‘frightful air-raids’ in Croydon during the Great War and wrote that ‘the terror I felt there still remains so that now an air raid is the thing I dread most’.Footnote 127 A London bank clerk, born in 1908, ‘was in several air raids … I have never been so scared in my life. I have also seen bombed houses. This is one reason for my hating war and not swallowing talk about glory.’Footnote 128 A woman born in 1905 recalled air raids on Margate during the Great War; in early 1940, this memory caused her to leave London ‘as I would not stand the strain’.Footnote 129

Fear was far from the only influence that respondents expressed, though, and not all of those who perceived impressions of the Great War to be influential saw them as a negative influence on their morale. An architect's assistant from London, born in 1913, reflected on his childhood during the Great War; with Britain at war again he felt ‘as though back in a country I had once known many years ago … [Although] the principle of war is against all my reason, I feel a very strong attraction to military things, and in some respects I am looking forward to joining the army.’Footnote 130 A research director from London felt growing up in the Great War meant he was prepared for ‘discomforts of all sorts’.Footnote 131 A factory worker from Oxfordshire, born in 1907, had clear memories of the enthusiasm he, and those around him, had felt during the Great War. He thus believed:

a lot more enthusiasm is needed to win this war. I'm quite willing to take my place in the forces when the time comes. And of course, I think that we are having a very easy, comfortable time up to now and should be prepared to put up with at least as thin a time as I had in the last war without grumbling.Footnote 132

While showing his own willing, his response also supports the finding that many were dispirited and discontented during the Bore War. Raising one's enthusiasm could be difficult for those still counting the costs of the last war; a sense of repetition accelerated war weariness. A forty-nine-year-old teacher from London expressed the resentment she felt towards both world wars: the last war had spoilt her career, denied her husband promotion, and ‘stopped all our homemaking plans’ and ‘indirectly it cost me my children’. ‘Now after twenty five years it has again divided our home, taken my job, left me to fight depressions and bitterness.’ ‘Worst of all is the dreadful feeling that none of these wars need have happened if people had been kind and sympathetic and generous to one another.’Footnote 133 Vicarious experiences of trauma occasioned by the last war also shaped some respondents’ attitudes to the Second World War. A thirty-five-year-old newspaper editor from Ilford provided an (unsurprisingly) eloquent list of his memories of the last war, with trauma (my emphasis) strung throughout:

The main memories I retain of the last war are: Watching wounded men being taken from ambulance trains at the station; looking anxiously at the newspaper contents bills each evening on my way home from school, hoping that I would see ‘war ends’ on them; the agony on those days when my father had to return to France after leave; watching my mother work herself almost to death because (though I did not then appreciate it) of the inadequacy of her army allowance; queuing for food; watching soldiers training in a field and learning the next week that they had gone to France and had been practically wiped out; the inexpressible relief of armistice day 1918.

Watching the last war had shaped his belief that ‘there is no sense in war and the enormous suffering it occasions could be avoided by tolerance’.Footnote 134

In November 1939, MO highlighted another reason for a lack of enthusiasm. They reported that there was ‘a lot of depression about [the war]’ because it caused economic troubles and ‘a number wish it was evaded mainly on these grounds’.Footnote 135 A street survey with an unemployed woman and her son demonstrates that such attitudes could be informed by memories of the Great War's effects. She said, ‘I wish it was all over. My husband says that after this war we shall be living in terrible times – worse than after the 1918 one.’ When her son suggested that ‘It's the people that put the young fellows to the war that ought to go’, she added, ‘It's always us working and poor people that suffer, you know.’Footnote 136 She was not alone when she connected the last war to her sense of a disconnection between the interests of the ruling classes and the ‘working and poor people’. In January 1940, a fifty-year-old working-class man in Bolton suggested that the current war was down to ‘politics and high finance … really. Same as the last war.’Footnote 137 Another drew parallels between action in Norway and the last war to illustrate the idea that those in charge did not care about the lives of those who fought.Footnote 138 These remarks suggest that the suspicions some Britons had about whom the MOI meant by ‘Us’ when they proclaimed ‘Your Courage, Your Cheerfulness, Your Resolution, Will Bring Us Victory’ were, at least for some, informed by understandings of the last war.Footnote 139 Yet, despite her doubts about the equality of sacrifice and the distribution of benefits, and her wish for the war to be over, the unemployed woman accepted the necessity of the war: ‘Course, it would be better than having a dictator over here wouldn't it? That would be terrible.’Footnote 140 Her remarks were, then, a good example of the ‘Defendism’ that Harrisson described – so long as Hitler was a threat, not fighting was not an option. This understanding did not make the Bore War any more enthusing or interesting, though.

The boredom of the present conflict could be exaggerated by comparison with memories of the last war, as a grocer in Ripon, born 1909, explained. He recalled the Great War as full of ‘excitement, impending calamities, bands and marching, different uniforms, English, Scottish, Canadian, Australian … The Germans always there as the arch-enemies. All in clear black and white. These memories make the present seem colourless by contrast. No excitement, no clear-cut right and wrong, money short, likewise tempers.’ Moreover, supporting MO's observations about the government's lack of clearly defined war aims, he added ‘Defeat of the Germans seems not victory but just a prelude to worse things, if we attempt to re-establish Poland and Czechoslovakia. If not – what are we doing?’Footnote 141 A masseuse from Surrey, born in 1907, was ‘probably about 75% convinced that this war is right, but for the rest feel it is merely inevitable; consequently I can never feel thoroughly enthusiastic’. She recounted memories of food and fuel shortages, the blackout and the fear of air raids during the Great War, but also ‘pleasantly exciting things’, like

talking to German prisoners working in the fields round our house … watching a train load up with troops, with a band and much singing; and especially the fun of Armistice Day [1918] at school and home. And later the victory procession in London, to which we were all taken. Such childhood impressions of a war still stick, and I think I tend to think of war as being unpleasant and frightening, but also exciting. I wonder whether part of one's depression and irritation is due to the fact that it has so far been mainly unpleasant, without being very alarming or exciting.Footnote 142

The inactivity of the Bore War and the legacy of the Great War informed the apathy of a woman from Kirk Sandall in Yorkshire, born in 1923, and those around her: ‘We aren't really a bit interested in the war. Possibly this lack of interest is due to our early education which taught us the futility of war, or perhaps it's due to this war itself which has failed to produce any very exciting event.’Footnote 143

Others also suggested the lack of current enthusiasm resulted from lessons learned from the Great War. A clerk from Kingston-upon-Thames, born in 1904, had learned that war was ‘folly’. He recognized that ‘as yet you cannot get rid of war but I feel that very few people now want war’.Footnote 144 Lessons were not limited to the ‘folly’ of war, though. A student from Yorkshire, born in 1914, was ‘strongly anti-war’ because of his upbringing but was not a pacifist. He wrote ‘I have not made my mind up about the present conflict. I cannot help thinking at times, drawing remembrances from the last war, that we are being led up the garden path again. I am suspicious of anything this government says or does.’ He also felt the ‘immense amount of anti-war propaganda to which we have been subject in the last 20 years’ has ‘helped to produce the lack of enthusiasm for the war which was so pronounced in the 1914 struggle’.Footnote 145

Over the interwar years, Armistice Day, which increasingly framed Great War sacrifices as worthwhile because they had secured peace for future generations, became an annual component of this ‘anti-war propaganda’. Although formal Armistice Day commemorations were widely observed, the most appropriate mode and message of remembrance were contested, particularly by veterans.Footnote 146 On the morning of 11 November 1937, four Great War veterans queued together in Bolton's Labour Exchange and discussed the inequality of Great War sacrifice and the hypocrisy of the commemoration. As far as they could tell, although supposedly valued ex-servicemen, their welfare was of little interest to those who wore poppies, and they wondered how the money raised by the sale of poppies helped veterans:

all them buggers at Town Hall Square [for the local Armistice ceremony] are fucking hypocrites. Who gets all the bloody money any road? You go to Scott House [where the Bolton Guild of Help was located] and they'll tell thee to take a bloody walk. All this fucking poppy business is all balls.

They noted, with considerable resentment, the difference between their own circumstances and those of the local elite (whom they described with cruder nomenclature) who had not served during the Great War: ‘I know what I've had for my breakfast – fuck all!!! But some of those bald-headed bastards who are at the front of those steps will have had ham and eggs and Christ knows what to finish up. Let ‘em talk to [me] about bloody Armistice … they'll not ask again.’Footnote 147 Later that morning, the ‘illusion of unanimity’ about Armistice Day was challenged on a national stage.Footnote 148 Stanley Storey – a Great War veteran, and escaped mental patient – broke the two-minute silence in Whitehall: he ‘rushed out into the roadway, shouting in a high tormented voice, “All this Hypocrisy!” and … “preparing for war”’.Footnote 149 Storey's sentiment – that it was hypocritical to commemorate Great War sacrifices as the guarantee of peace for future generations while at the same time enacting policies of rearmament or appeasement, either of which could be seen as placing the peace in jeopardy – was perhaps more widely held as the Second World War loomed than resentment about who had won and lost in the pursuit of victory between 1914 and 1918.Footnote 150 The two meanings that Armistice Day had acquired by 1939 – victory and warning – were undermined when war returned.Footnote 151 A member of the public told an MO observer that the cancellation of Armistice Day in 1939 was the correct decision: ‘it's right, it would be a farce to celebrate the “war to end war” with a new one started’.Footnote 152

If ‘a popular attitude to remembrance’ could be discerned in 1939 once the peace had been lost, Noakes suggests ‘it was one of bitterness at a perceived betrayal of the dead of the Great War’.Footnote 153 This attitude was present in the February 1940 directive response of a female writer, whose reply suggests her childhood was before the Great War. She thought ‘this war not only boring, but hateful and heart breaking’ because the League of Nations, disarmament, and ‘hatred of war itself as an absolute evil’ had to be ‘put into cold storage for the present’. She expressed her ‘sense of shame because the last war was fought to no purpose and we squandered the peace’.Footnote 154 That this attitude was present amongst the February 1940 responses shows that the understanding of the Second World War as a betrayal of the memory of the First World War was not limited to reflections on Armistice Day; it was also an attitude found outside the context of commemoration and which informed Briton's broader feelings about the Second World War. Indeed, the directive responses reveal that the understanding of the Great War disseminated by commemoration of the Great War remained a powerful influence in 1940.

Noakes found that in the late 1930s, Armistice Day remained significant and potentially traumatic for those who had direct experience of the Great War, or who had been bereaved by it, but that ‘rituals of remembrance’ had little affective resonance for many, especially those too young to have a personal connection to the war.Footnote 155 The responses to the February 1940 directive do not contradict this. They do, however, emphasize the continued significance of the didactic, rather than emotional, function of Armistice commemorations during (and probably earlier in) the interwar period, which had framed the Great War as the war to end all wars. This message was reinforced by organizations such as the Peace Pledge Union (PPU) and the League of Nations Union (LNU), which mobilized the Great War to educate young Britons to peace.Footnote 156 These were not insignificant organizations; the strictly pacifist PPU reached 120,000 members, while the ‘pacificist’ LNU, which would countenance war only if all other measures failed, could state that one million Britons had been members between 1920 and 1933.Footnote 157 At a local level, the LNU was predominantly middle class.Footnote 158 Nevertheless, such messages likely met a receptive audience. The responses of eleven million Britons to the 1935 ‘Peace Ballot’ suggest widespread support for a ‘prudent middle way between isolationism and militarism’.Footnote 159 The LNU provided schools with guest speakers and teaching resources, and established junior branches and study-circles.Footnote 160 An education to peace clearly continued to resonate with some of those who had come of age after the Great War, like a male clothing manufacturer's assistant from Ipswich, born in 1922, who said: ‘Childhood told me war was always unnecessary and also taught me to hate it. I still hate, I still think it unnecessary.’Footnote 161 Similarly, a twenty-five-year-old teacher from Chesterfield felt the waste of lives and resources made the Second World War ‘sheer stupidity’ because she had been ‘brought up to believe that the Great War was a war to end wars’ and for a long time ‘could not realise how statesmen could be such fools as to allow wars to develop’.Footnote 162 While this pair did not describe the origins of their attitudes, their views mirror the proselytising of the PPU and LNU, and others directly recall their influence. A twenty-three-year-old civil servant from Harrow expressed her ‘present scepticism about the war. Also from earliest times I had heard of the Great War as a terrible thing which had happened in the past, to make a new world possible. It was a bad mistake which would never be made again. I did not dream that it could happen again.’ She was, along with all her school peers, a member of the LNU; like ‘all people of my age … we were educated to peace. It is hard now to change one's attitude to war.’Footnote 163 A male solicitor from London, aged twenty-four, had a similar experience and expressed a similar attitude. He ‘felt that after our peaceful upbringing we should not be much use if called upon to fight after all; it also made me wonder if it could be right to ask us to make such a complete switch round in our attitude’.Footnote 164 Some had no intention of doing so. A man from Cheshire, born in 1904, felt his ‘childhood impressions’ ‘stiffen my objections to the whole blessed business and compel me to think out just how I can escape being dragged into it as a soldier’.Footnote 165 This may explain why he had become an auxiliary fireman. These directive respondents held lower-middle-class or middle-class occupations, and were relatively young, but MO street interviewers in Bolton in November 1939 heard similar sentiments expressed by older, working-class people, albeit without explicit reference to the peace organizations. A forty-four-year-old Great War veteran told MO ‘If it could have been avoided it would have been worth making almost any sacrifice, but I think Germany would have made war anyway. I'm not a supporter of war, I hate the idea. It's abominable to me.’ A fifty-five-year-old woman said earnestly, ‘I wish it was over and finished with: and after that we want no more war, but world peace for ever and ever, and I'm sure every sensible person must agree with me. It's terrible when you've got somebody there in France, fighting. I want peace for ever.’Footnote 166

While the interwar education to peace, itself a legacy of the Great War, caused some to perceive the Second World War as a betrayal of those who had fought the Great War, it created more emphatic, passionate responses in others, whose attitude to the Second World War was shaped by a feeling they had been betrayed by the older generation. A twenty-six-year-old woman from Essex, working in Air Raid Precautions, had

read glowing accounts (in the children's newspapers chiefly) about the formation of the League of Nations … Heard of all the terrible things that happened between [19]14 to [19]18 … Felt glad that the ghastly business was a thing of the past. Now it seems that this was only the first ‘war to end wars’. I wish our statesman would stop dishing up the same old topic. Would it be better if we were trained to expect a war every 25 years? I have a feeling of being tricked and cheated, not by Hitler and his gang, but by my own people … It's all very well to say war is better than slavery, but will 5 to 10 years under present or worse conditions be really worthwhile?Footnote 167

A female civil servant from London, born in 1912, had been ‘aware of war as a horrible background to life’ in her childhood and recalled the ‘tremendous excitement of peace’, after which she was taught that future wars would be prevented by the League of Nations. She had believed that war was ‘very horrible [and] that it was gone forever’ and now felt ‘ruthlessly deceived by those whose words I valued’. She resolved to ‘believe few official theories, to detach myself inwardly from this reeking whirl of events which I hate and despise and am bored by’.Footnote 168 A garage assistant from Norfolk, born in 1913, expressed a similar sentiment in angrier tones. She detailed a number of unpleasant memories of the Great War, ranging from seeing soldiers kicking and screaming because they had to go back to the Front to the ‘horrid stuffy smell’ of the cellar used during air raids. She and her family were members of the LNU and PPU and she could not ‘think of anything pleasant in any way connected with war’ or ‘see any reason to encourage or enthuse over this one’. She sought to ‘avoid any contact with it’. When going to the cinema, she tried to ensure she only saw the picture because ‘I loathe seeing anything to do with war. Grinning young men being herded off to another war to end wars, silly asses, I can remember well the other side and have already heard enough said about this one by those who have been deluded into it.’ She concluded, ‘I do not feel at all interested in the stupid naval battles etc., they do not seem important to me, I regard the matter as to boatloads of unbalanced men and best exterminated. The whole thing strikes me as being very childish, if I bother to think about it at all.’Footnote 169 Her younger sister, born in 1921, worked with her at the garage. Without memories of the war, she highlighted that she had been educated to peace by her family and was greatly impressed at the school's ‘celebration of armistice day’ ‘when we heard of the men that died in the war that was to end war’. When her father said there might be another war, she

was horrified. I could not think such a thing possible. It could not happen again to us. I would not believe it. Why, did not our headmistress say on Poppy Day ‘war to end war’ … I feel hardly now able to believe that this unthinkable thing is upon us, and any day I may suffer as my elders suffered before.Footnote 170

VII

In War begins at home, Harrisson and Madge worried morale was low. The expressions of distrust in political leadership found in the MO material support their suggestion that it was not yet ‘everyone's war’ in early 1940. Middle-class respondents voiced concerns that Britons were being ‘led up the garden path again’, while working-class Britons emphasized the class component of their distrust, like those surveyed in Bolton who suspected that, as in the Great War, neither losses nor gains would be equally shared. Others were reluctant to accept that war had returned, as both MO and Kingsley Martin had suggested. Nevertheless, individuals’ evident disappointment that Britain had been forced into a conflict they lamented and expected to be destructive did not typically metamorphose from Harrisson's ‘Defendism’ to demanding the state ‘stop the war’. Although Britons grumbled about boredom and paradoxically wished for excitement, MO material and BIPO polls suggest most were not apathetic but were resigned to defending Britain and their own interests against the threat of Hitler's Germany. Harrisson's suggestion that Britons had not yet ‘begun to realise … the almost intolerable strain which active prosecution of this war will call for’ is difficult to support. The minor expressions of resistance within the material examined here are often best understood as frustrations expressed as recalcitrance but which bore little connection to individuals’ ultimate convictions, and/or as resulting from individuals waiting for the strains that they expected were still to come. They did not have to wait long. In April, May, and June 1940, British forces withdrew from Norway, the British and French armies were pushed to, and then from, the French coast, and France, Britain's most significant ally, signed an armistice. Even then, Britons largely remained determined and optimistic.Footnote 171

For all their interest in Armistice Day, MO did not look to connect the two world wars. Analysis of the directive responses reveals the diverse ways that the Great War featured in Britons’ ‘subjective worlds’ in 1940.Footnote 172 Of course, not all Britons felt the Great War influenced their response to the Second World War, even when it had had significant effects upon their lives. For instance, a chief electrician from Blackburn, born in 1901, stated: ‘My father was killed in the last war; I am not conscious of any effect that this has on my opinion.’Footnote 173 Nevertheless, the replies to question eight of the February 1940 directive and other MO material, particularly the Worktown collection, demonstrate the Great War's continued significance during the Bore War. When faced with the Second World War, Britons commonly expected people would look backwards to the Great War, and a significant proportion of respondents felt that the Great War influenced their attitudes. The material examined here supports Francis's suggestion that memories of trauma during the Great War shaped some Britons’ reactions at the outbreak of the Second World War.Footnote 174 It shows that trauma might have been experienced personally or vicariously, but also that traumatic memories were only one aspect of a wider and more varied legacy of the Great War that informed Britons’ attitudes to the Second World War, often in ways that were detrimental to morale during the Bore War. Importantly, it was not only those who had served in, or even lived through, the Great War who felt that their understandings of the Great War affected their attitudes in 1940, but people of all ages. When they ascribed influence to the Great War, people of different ages drew on different types of knowledge: personal experiences, vicarious memories, and post-war representations. Younger respondents were more likely to be reliant upon learned rather lived experience – references to post-war familial narrations and representations of war in popular culture increased as respondents’ ages decreased – but those who were able to ascribe influence to personal memories of the Great War tended to do so. Those with strong personal memories felt no need to rely upon others’ interpretations of the meaning or lessons of the Great War. Public discourse about the Great War may have informed individuals’ interpretation of their personal memories, but unpicking the complex interplay between personal and cultural memory is difficult at this remove. While the attitudes displayed by directive respondents are often consistent with those presented in the now canonical war books, those who referred to cultural representations of the Great War more often pointed to a much wider body of representations and memories. For instance, Armistice services and more nebulous lessons about the meaning of the Great War were more commonly cited as influential and more readily used to articulate feelings of disappointment and even betrayal during the Bore War. These findings complicate the assumption that cultural representations of the Great War determined Britons’ responses to the outbreak of the Second World War, particularly as the directive respondents’ typical education and reading habits mean they were more likely than most to have encountered representations of the Great War in high culture, and were likely more receptive than most to the influence of anti-war literature.Footnote 175 This article makes clear, however, that the legacy of the Great War held a significant position in the subjective worlds of many Britons, of all ages, as they formed and articulated their attitudes to the Second World War in its early months. The resignation, limited enthusiasm, fear, dismay, and even the boredom, that characterized the Bore War cannot be fully understood without acknowledging that some Britons could not help ‘drawing remembrances from the last war’.Footnote 176