The competitive, often antagonistic relationship between private and public higher education has fundamentally shaped the US educational landscape and its mixed public-private character, and yet these institutional types are often treated separately in historical scholarship.Footnote 1 This paper explores the conflict between these institutional types in Boston, exemplified in the long struggle for a public university between 1890 and 1980. Despite decades of advocacy, private institutions successfully prevented the founding of a public university in Boston until the 1960s. The opening of the University of Massachusetts Boston in 1965, however, did not so much indicate the reversal of the public-private balance of power, but rather a temporary accommodation. Fiscal crises beginning in the 1970s allowed private institutions to return to their dominant position in the educational landscape.

The chronology of public higher education has varied widely across the United States. By the late nineteenth century, the definition of a “university” was not fixed, but in a US context it most often described a degree-granting college with additional academic units in professional fields such as divinity, medicine, law; broader practical subjects like science and agriculture; and in some cases graduate and doctoral programs.Footnote 2 Public institutions in western states such as the University of Michigan and University of California became degree-granting state universities, complete with a diverse range of professional and graduate programs, by the 1870s. While Post-Reconstruction era southern states were especially frugal with regards to public educational spending, state universities such as the University of North Carolina touted professional schools for teacher training, law, and medicine by the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 3 Northeastern states, on the whole, incorporated their state universities relatively late: while the University of Vermont became a state land-grant university in 1865, New Hampshire and Connecticut incorporated their state universities in 1923 and 1939, respectively. Massachusetts opened its state-funded land-grant agricultural college in 1867, but did not have a state university until 1947. Despite long having one of the best funded and enrolled public-school systems in the country, Massachusetts was second to last (only to Tennessee) in a 1944 state ranking of per capita public expenditure on higher education.Footnote 4 The Boston area, home to between one-third and one-half of the state's population between 1880 and 1980, lacked any public institution with general degree-granting power until the 1960s. Even by northeastern standards, Boston stands out: New York, for example, did not launch a state university until 1948, but New York City was home to several thriving municipal degree-granting colleges that date back to the mid-nineteenth century.

The varied landscape of higher education across states in the US can only be explained historically by a careful reconstruction of local and regional political economies of education. In Massachusetts, the curbed growth of public higher education was largely due to powerful private institutions, concentrated in the Boston area, that viewed public higher education as a threat. Their financial interests profoundly shaped the development of local and state education policy, including state-controlled authorization of degree-granting power and budgets for higher education spending. As Riesman and Jencks observed in 1962, public higher education in Massachusetts was largely restricted to “the residual functions that the private system cannot, or will not, fulfill.”Footnote 5 Massachusetts was perhaps the most extreme case of the pattern typified by northeastern states, in which the early establishment of private colonial colleges (such as Yale in Connecticut and Columbia in New York) restricted state-funded higher education. Western states, by contrast, tended to have less entrenched private institutions, which allowed public higher education to expand and flourish earlier.Footnote 6

The failure to establish a public university in Boston until the late twentieth century was not for lack of trying. Organized labor had proved one of its strongest and most consistent champions, advocating for a free, public university in the city since at least 1888. Proposals for such an institution were repeatedly brought to the legislature, but repeatedly rejected, and a wide range of public-private alternatives were implemented instead. The founding of the University of Massachusetts Boston in 1965 represented a significant milestone in this nearly century-long struggle. However, even this achievement was only a partial victory. During a time of booming student enrollment, when public and private institutions increasingly catered to distinct student bodies, resistance of private universities against a public competitor had waned, creating a temporary political opening. But by the 1970s, subsiding enrollment pressure and fiscal concerns led state officials once again to align with private institutions to limit the expansion of public higher education.

A close examination of the long struggle for a public university in Boston has several important payoffs. First, it reveals how the competitive relationship between public and private institutions was a central force in shaping the history of each sector. While the mixed public-private landscape of American higher education has been noted as a salient feature, this article deepens our understanding of conflict and contestation between them.Footnote 7 At the same time, this history complicates a clear dichotomy between the two sectors. Many private universities were originally chartered by the state of Massachusetts with provisions for state representation on governing bodies, and received public funding. Ideologically, many private university leaders and public officials understood these institutions as public-serving, and used this argument to repeatedly undercut political support for free, publicly funded alternatives. A diverse array of public-private partnerships developed through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, revealing complex and long-lasting interrelationships between government bodies and private institutions.Footnote 8 Even purportedly public institutions reflected the influence and practices of their private competitors, including student tuition, fundraising from private sources, selective admissions policies, and marketing practices. This influence can help explain distinctive features of US higher education, including its unusually high cost to students.Footnote 9

This history also recasts our understanding of many innovations in educational history, including state scholarships, teacher-training initiatives, university extension, correspondence courses, and junior colleges. These innovations have often been interpreted as additions to the educational landscape intended to expand access and opportunity.Footnote 10 In Massachusetts, however, the historical evidence suggests that they first emerged in political debates as substitutes for a public university. In this story, therefore, these educational departures can be usefully reinterpreted as strategies to limit the expansion of a robust public sector.Footnote 11

This history should also prompt a reinterpretation of our current neoliberal moment. Taking a long view, public higher education in Massachusetts is a history of education under conditions of fiscal austerity. In the 1960s, public higher education in Massachusetts received abundant levels of funding—financing the expansion of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, the construction of UMass Boston, and a network of community colleges—which reflected a “golden age” of public higher educational expenditure across the country. This golden age, however, was an exceptional period.Footnote 12 Rather than view contemporary budget cuts as a novel historical departure of the late twentieth century, they feature in this story as a return to a political landscape long hostile to public higher education.Footnote 13 Public subsidies of private enterprises and public-private partnerships also appear, in this long historical sweep, less as contemporary innovations and rather a return to older practices. This Massachusetts story, therefore, reveals a long history of private power that increasingly structures higher education across the country today.

Public-Private Foundations of Massachusetts Higher Education, 1636–1900

The earliest colleges in Massachusetts blurred the boundary between public and private. In 1636, the Massachusetts Bay Colony granted 400 pounds to a “college . . . instructing youth . . . after they came from grammar schools.” What became the chartered corporation of Harvard College in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was understood to carry out the essential public function of providing a liberal education to Puritan ministers.Footnote 14 The 1780 Massachusetts constitution made it a “duty of legislatures and magistrates . . . to cherish the interests of the literature and the sciences . . . especially the University at Cambridge.”Footnote 15 The state-chartered corporation, granted specific legal powers, became a common way for states to further public objectives through private agencies, from infrastructure projects to education. These corporations were understood as serving the public interest and granted significant privileges, including state funding.Footnote 16 Although an 1853 “anti-aid” amendment to the Massachusetts constitution, passed at the height of anti-Catholic nativism, barred the state from directly funding private “sectarian” institutions, this act excluded higher education. Between 1786 and 1918, state funding directly subsidized Harvard University's personnel salaries, new buildings, and scholarships.Footnote 17 Finally, state charters often specified particular forms of public oversight. Between 1780 and 1865, the state mandated that several public officials, including the governor, serve on the Harvard Board of Overseers, one of Harvard's governing bodies.Footnote 18 While the Board of Overseers became fully elected by alumni in 1866, Harvard maintained close ties to the state.Footnote 19 As Herbert Adams wrote in 1889, “Harvard was really a State institution. . . . She was brought up in the arms of her Massachusetts nurse, with the bottle always in her mouth. . . . [Harvard has] always obtained State aid when it was needed.”Footnote 20

Nineteenth-century proposals for “democratizing” higher education often advocated for more state aid to existing colleges rather than creating separate, fully state-supported institutions. State aid to liberal arts colleges was a common practice in other northeastern states where private institutions had deep historical roots. A 1849 Massachusetts legislative committee recommended that in order to “[popularize] the colleges and [bring] them into harmony with the great [public] school system of Massachusetts,” the state should create an additional school fund to aid Harvard, Williams, and Amherst.Footnote 21 In the wake of the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862, as officials debated how to best use federal funding to “promote liberal and practical education of the industrial classes,” Governor John Andrew proposed creating a “state university” by merging Harvard University with the recently chartered Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and additional professional schools.Footnote 22

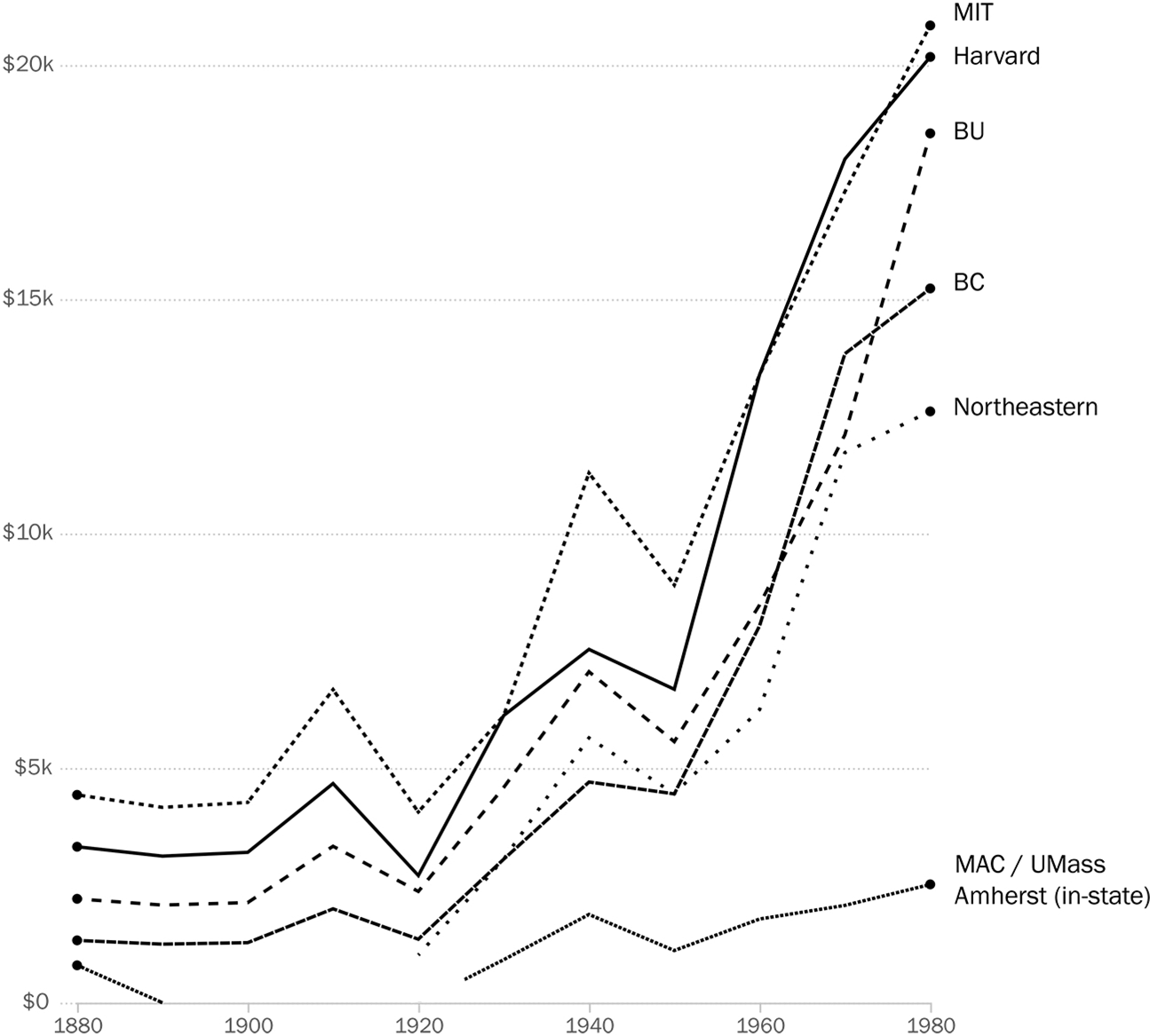

The earliest state institutions of higher education in Massachusetts also shared characteristics with existing private colleges, including a mix of public and private funding. Federal funds provided by the 1862 Morrill Act provided partial funding for two degree-granting institutions in Massachusetts. Two-thirds went to the Massachusetts Agricultural College in Amherst, which opened in 1867 with additional support from private subscriptions as well as student tuition and fees (although after 1883 and for several subsequent decades, nearly all in-state students were provided full scholarships).Footnote 23 The other third went to MIT, which had also been awarded public land in Boston's Back Bay on the condition that the institute raise $100,000 privately.Footnote 24 Like the mixed status of the privately endowed, land-grant institution of Cornell University in New York, land-grant status provided MIT with an influx of federal funding, and like Harvard, the state mandated that several state officials serve on its governing body.Footnote 25 Although the majority of its funding came from private donors, MIT would continue to receive state aid in the form of scholarships through the early twentieth century, which covered the highest tuition rate in the Boston area (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Annual Student Tuition at Selected Massachusetts Colleges and Universities, 1880–1980 (estimated, in 2021 dollars). Sources: Report of the Commissioner of Education, 1880 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1882), 668, 682; Report of the Commissioner of Education, 1901, Vol. 2 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1902), 1694–1697, 1724; Biennial Survey of Education, 1918–1920, Statistics (Washington, DC: GPO, 1923), 390–91; MIT Course Catalogue, 1880–1960, Institute Archives and Special Collections, Cambridge, MA; Boston College Bulletin, 1930–1960 (Chestnut Hill, MA); Freeland, Academia's Golden Age, 128, 152, 269; “Hard Times,” BG, Oct. 5, 1930, 56; “Oppose Boosting College Tuition,” BG, Feb. 14, 1934, 17; “10,000 Will Return to BU,” BG, Sept. 20, 1937, 12; “Northeastern Boosts Tuition,” BG, Feb. 25, 1938, 14; “Northeastern to Enroll Record,” BG, Sept. 5, 1948, C16; “BU Boosts Tuition,” BG, April 23, 1952, 11; “Cost of College,” BG, March 20, 1958, 18; “UMass Trustees Ask Tuition Hike,” BG, Jan. 7, 1959, 14; “State Opens First Two-Year Public College,” BG, Sept. 18, 1960, 55; “Tuition Charges,” BG, Feb. 20, 1970, 6; “Tuition Increase Expected at UMass,” BG, May 1, 1979, 18; “N.E. College Cost-Rise,” BG, March 9, 1980, 25; National Bureau of Economic Research, Index of the General Price Level for United States (M04051USM324NNBR), retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M04051USM324NNBR, June 15, 2020; CPI Inflation Calculator, https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

As western states including California, Michigan, and Illinois launched or expanded their state-funded universities in the late nineteenth century, calls for wider and cheaper access to higher education, in a broader range of curricular fields, gained popular support in Massachusetts. But whether these demands would be met by public or private institutions was an open question. After the Civil War, Harvard President Charles Eliot articulated a growing critique of public institutions, arguing that state dependence “[sapped] the foundations of public liberty” and exerted partisan influence.Footnote 26 It was in this era that “private” became a more common designation for universities like Harvard, whose leaders touted their institutional autonomy from corrupting political pressure, and reflected their turn to philanthropic donations for financial support.Footnote 27 In an era of flourishing voluntary associations and civic projects funded by wealthy donors, university leaders also drew on the tradition of public-serving corporations to argue that “independent” institutions could best serve the public interest. Eliot, for example, believed Harvard to be a steward of the public interest through the training of a cultural and technical elite.Footnote 28 Even champions of a public university like Reverend Adolf Augustus Berle, a Congregational minister in Boston, acknowledged that the need for a public institution would be lessened if Harvard could fulfill this role instead: as he put it, if “our great Massachusetts colleges and schools, with Harvard at their head, can formulate some plan which will make it possible for their doors to swing open as readily as do the doors of the great state universities of the west.”Footnote 29 Existing institutions also responded to public pressure for greater access. In 1903, MIT president Henry Smith Pritchett argued that the cost of tuition and living expenses in Boston were cutting off worthy applicants from higher education. Rather than a state university, however, Pritchett argued that private institutions should solve this problem, and proposed expanding MIT's dormitories “to give to the poor student the opportunity of economically living.”Footnote 30 On a practical level, private university leaders recognized that if they did not address the growing demands for accessibility and affordability, support for public alternatives would grow.

Degree-Granting Power for the Normal School, 1852–1902

Boston's private institutions repeatedly mobilized against legislative efforts to expand public higher education. One of the earliest efforts was a school committee proposal to authorize degree-granting power for Boston's Normal School. The only form of postsecondary education provided by the city since 1852, the Normal School trained Boston's elementary school teachers—tuition free for residents of Boston.Footnote 31 To become a high school teacher, however, the Boston School Committee required a college degree, at the time only provided by private colleges. The first private women's college in the Boston area, Wellesley, only opened in 1875. By 1900, Wellesley and Radcliffe charged even higher tuition rates than Harvard.Footnote 32 While cities like New York had successfully won degree-granting power for a municipal public college (renamed the College of the City of New York in 1866) and a Normal School (Hunter College in 1888), advocates of a teachers college in Boston faced greater obstacles.

By the turn of the century, the fault lines that emerged in the Normal School debate reflected Boston's class, ethnic, and gendered politics. By this date, the majority of elementary school teachers were Irish women, a demographic profile that was concerning to some administrators. In 1899, the superintendent of Boston's schools, Edwin Seaver, argued that “staff recruited all from one source inevitably becomes narrow, conceited, and unprogressive,” and espoused the merits of recruiting more “outsiders” into the Boston teaching force, in effect code for wealthier, Protestant, private-college graduates.Footnote 33 He was also eager to recruit more men to the teaching profession. Among those who shared Seaver's views was Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the future president of Harvard, who served on the Boston School Committee from 1896 to 1899. Lowell, a descendant of one of Boston's most established First Families, was a fierce immigration restrictionist, and in 1898 he helped to put in place a Normal School “merit list,” on the basis of which graduates were chosen for positions.Footnote 34

Leading the opposition to Seaver and Lowell's reforms was Irish working-class champion Julia Harrington Duff, an 1878 graduate of the Boston Normal School and former teacher in the Irish neighborhood of Charlestown. As a strong defender of job opportunities for Irish Bostonians, she used the rallying cry “Boston schools for Boston girls” to mobilize popular support for Normal School graduates, which effectively won her a seat on the Boston School Committee in 1901. She argued that the criteria used to judge the “best” teachers was a cover for discrimination against Irish women. Duff had the strong support of organized labor, and working-class Irish Catholics formed the base of support for the Democratic Party in Boston.Footnote 35

By 1901, Duff and her working-class allies had built up a large constituency of public officials that supported degree-granting authority for the Normal School, which would enable it to offer credentials to compete against private colleges.Footnote 36 In December, the school committee unanimously voted to petition the state legislature to make the Normal School a teachers college. However, allies of Lowell gained strength on the school committee in that year's election, and were able to appoint their supporters to author a report that ordered the withdrawal of the school committee's petition. The report argued that drawing teachers solely from Boston would hurt the caliber and quality of the teaching force, and a public teachers college would duplicate efforts provided for “admirably” in private colleges and universities. The danger of duplication was a common argument used across the United States to restrict the scope of public higher education as well as improve efficiency in both the private and public sectors.Footnote 37 The authors, however, did not openly state their conflict of interest as advisers and investors in these private institutions.Footnote 38

Duff submitted a minority report that argued the concern with “caliber and quality” reflected prejudices of the supervisors against Irish women, and that a teachers college would not duplicate opportunities because “only the children of the wealthy . . . can afford to attend [private] universities.” She concluded by declaring that the history of education in Massachusetts recounted a war waged by the propertied class against the working-class women of Boston, with the opposition to the teachers college only the most recent battle.Footnote 39

The teachers college proposal was defeated. The entrenched power of private colleges in the city, as well as the partisan lines on which the battle over the Normal School was fought, prevented the city from sponsoring its own degree-granting institution. Normal School graduates continued to be barred from teaching in Boston's high schools, as private colleges channeled their own graduates into the highest-paid public jobs open to women. By 1907, six private institutions (Boston University, Simmons College, Wellesley, Tufts, Harvard, and MIT) were coordinating with the Boston School Committee to offer teachers part-time and summer courses toward a college degree, bolstering the argument that the needs of teacher training were already provided by the private sector. Hopes for a public degree-granting college in the city of Boston were put on hold.Footnote 40

Organized Labor and Public-Private Substitutes, 1888–1918

Labor unions proved to be the most powerful and consistent advocate for public higher education in Boston. Their power grew in the late nineteenth century among craft workers affiliated with the American Federation of Labor, and they became a chief base of support for the Democratic Party at the local and state level, aligning with Boston's increasingly powerful Irish working class. Although very few craft workers attended college, most believed that higher education should in principle be open to all. In 1888, the Boston Central Labor Union “most heartily and unqualifiedly” endorsed a proposition to introduce a university-level course into the public school system “so that our children may have the same educational advantage now only attainable by rich men's sons and daughters.”Footnote 41

For organized labor, access to higher education was not simply about affordability, but about who controlled these institutions and the interests they served. Boston's craft unions opposed a wave of private trade schools that emerged in the early twentieth century, including the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Association Trade School (1900), the mixed public-private Franklin Union (1908), and Wentworth Institute (1911). Largely funded by wealthy employers, these schools, according to unions, circumvented the apprenticeship process, spread anti-union propaganda, and turned out strikebreakers.Footnote 42 Unions were also wary of local colleges and engineering institutes where employers drew a growing share of their anti-union management. Indeed, in many strikes of the early twentieth century—including those of telephone operators, police, and railroad workers—students at MIT, Harvard, and Boston University played key roles as strikebreakers, encouraged by their university administrators to do so.Footnote 43 On April 14, 1905, in the midst of heated debate over private trade schools, Peter Collins of the local electrical workers union declared, “Organized labor will have its own university of labor before long—one not dependent on false-natured philanthropists, such as Carnegie and Rockefeller.”Footnote 44

As early as 1895, many city and state officials supported a public university, agreeing with organized labor that educational opportunity should not depend on social class. That year, state representative Thomas F. Keenan proposed a bill to establish a “free university in the city of Boston.” As Senator Joseph Corbett of Charlestown stated in support: “Why should a child be debarred from the higher education on account of poverty?” The Boston Globe reported that “many senators and representatives . . . representing other sections of Boston . . . were all in favor of the bill.” Keenan's free university would cater to students upon graduating from grammar school.Footnote 45 At a time when high schools were known as “people's colleges,” the distinction between secondary and higher education was not yet firm. In this sense Keenan's model was similar to that of New York City's “Free Academy,” founded in 1847 and awarded general degree-granting power in 1854, which admitted students who had completed eighth grade and were at least fourteen.Footnote 46 Keenan argued that Boston's existing public high schools, Boston Latin and English High, provided a literary education rather than a practical education, such that “there are many young men who do not continue, for . . . they see no practical benefits to be obtained.” A free university, for Keenan, would provide training in a wide range of practical subjects leading into employment.Footnote 47

While many advocates imagined a public university as a centralized, state-supported institution, Massachusetts proposals often entailed some version of public-private collaboration. Keenan's free university would not require a “large and expensive college building” or even a full-time faculty. Rather, this university would use the facilities of existing public high schools after daytime classes let out, and recruit low-cost, part-time instructors from existing colleges.Footnote 48 While this free university never opened, these cost-saving measures foreshadowed future proposals that were developed as alternatives to a state university—including university extension and correspondence classes—as well as cost-saving labor practices increasingly adopted in the twentieth century.

Another short-lived proposal in 1909 was “Massachusetts College,” which was to rely on the facilities and personnel of both the public and private sector. The author of the bill to create the college, Edmund D. Barbour, was a retired Boston merchant who hoped to “give the degree of A.B. at low cost to those who really earn it, who have not the means for pursuing their education away from home.”Footnote 49 Like Keenan's proposal, Massachusetts College would use existing public-school facilities in thirty “college centers” across the state and borrow books from public libraries. The school would employ part-time instructors and offer courses to both men and women at thirty-four dollars per year, far cheaper than the hundreds of dollars in annual tuition of private universities in the Boston area.Footnote 50 A board of advisers would be made up of ex-governors, superintendents of schools, and representatives from fourteen colleges in the state, which, with the exception of Massachusetts Agricultural College (MAC), were all private. The college would not receive state funding directly, but would be financed by private donors who would sit on the board of advisers.Footnote 51 This plan was supported by many private university representatives, such as MIT professor Thomas Jaggar Jr., for whom it was “the most democratic and most interesting he ever heard of.”Footnote 52 When the governor signed the bill, it was heralded in the Boston Globe as “revolutionary,” and a sign that “higher education will soon be within the reach of everyone who desires to avail himself of the opportunity.”Footnote 53 Massachusetts College, however, never opened. The act that incorporated the new college was to take effect when subscribers donated a sum of $600,000, and despite Barbour's contribution of $100,000, this sum was never raised.Footnote 54

By the early twentieth century, petitions for establishing a state university were regularly brought to the state legislature by individuals or labor unions. Many specified a location in the Boston area, the state's major industrial center, home to about a third of the state's population in 1910.Footnote 55 In response, the state legislature authorized a series of investigations into state higher education, the authors of which were often private university administrators. The frequency and similarity of their conclusions suggest these reports were a useful tactic to respond to public pressure without committing to legislative change. These reports also reflected new political fault lines in Massachusetts: after 1910, the Irish-dominated Democratic Party, with the key support of organized labor, began a fifteen-year period of mayoral control of Boston, sharpening the partisan divide between the city of Boston and the Republican-dominated state legislature. The reports almost universally recommended against a state university, but proposed a wide array of public-private partnerships instead.

The 1912 State Board of Education, chaired by a member of Harvard's Board of Overseers and former AT&T president Frederick P. Fish, issued one such report in response to a legislative resolve to “investigate [the provision of] higher and supplementary education as a sequel to the public education now provided.” It acknowledged several arguments for a “State university”: the fact that high tuition barred deserving students, that Massachusetts residents were leaving the state to attend college elsewhere, and that high school teachers were not receiving sufficient professional teacher training at existing colleges. However, the report concluded that “the interests of education in Massachusetts do not warrant the establishment of a State university” because such an institution “would necessitate heavy expenditure” and would “result in a duplication of existing facilities.” State funds were better spent, the report concluded, on primary and secondary education. The board optimistically claimed that private institutions were “constantly increasing” their disposition to “render themselves the servants of public demand in every possible way.”Footnote 56

The report laid out several alternative recommendations that would put “the resources of [private] college and universities more fully at the command of the people.” The first was the expansion of state scholarships to be used toward tuition at private colleges.Footnote 57 Scholarships were a long-standing practice and were the favored policy solution of then governor Eugene Foss, a free-trade, anti-labor businessman elected governor in 1910. Foss repeatedly dismissed the idea of a state university, arguing in 1911 that it would “weaken” existing institutions and be too costly. Instead, he advocated for several hundred scholarships to private institutions.Footnote 58 His persistent campaigning on this issue likely helped push through state legislation that year to grant $1 million to MIT over ten years to fund eighty full scholarships. In 1912, a similar authorization for $500,000 was made for Worcester Polytechnic Institute.Footnote 59 The 1912 report, therefore, reiterated the wisdom of this practice.

Another recommendation of the report was to cooperate more closely with private universities on teacher-training programs, including the provision of scholarships for teachers to take professional education courses.Footnote 60 Since the defeated teachers college proposal, private universities had continued to expand their partnerships with the Boston School Committee for teacher training. By 1919, graduate courses at Harvard, Boston University (BU), and Boston College (BC) counted in place of two to three years of teaching experience.Footnote 61 Additionally, the report suggested creating an agency to connect expert knowledge from private universities to public administrative bodies, similar to ways public universities served states like Wisconsin and California.Footnote 62 Governor David Walsh, the first Irish Democratic governor of Massachusetts, elected in 1914, supported a plan to implement such an agency in conjunction with MIT, including placing faculty on state boards, making public use of MIT's laboratories and shops, and creating a new bureau of technical information. This plan was touted in the Boston Globe as a means of turning MIT into the “nucleus of a great State University,” indicating the continued understanding that private universities could fulfill essential public functions.Footnote 63

A fourth recommendation of the 1912 report was to develop a university extension system that, like Keenan's proposal in 1895, would rely on existing public facilities and part-time instructors. University extension was a well-established practice in states such as New York, Illinois, and Wisconsin, offering college courses in person or via correspondence.Footnote 64 In the Boston area, however, only private institutions offered extension courses. BU was the first to launch an extension program offering education courses to local teachers, and by 1910, eight private universities including Harvard, MIT, BU, Tufts, BC, and Simmons College all had extension programs. In the wake of the 1912 report, these institutions partnered with the State Board of Education and school districts in their extension work.Footnote 65 In 1915, the State Board of Education launched its own Department of University Extension and Correspondence Instruction.Footnote 66 The appointed advisory committee contained representatives of MAC and organized labor, but was dominated by representatives of private institutions, including Harvard, Tufts, and BC.Footnote 67 In twenty-eight districts across the state, courses were organized in public buildings with part-time instructors secured from private universities and industry; within the first year, nearly thirty-five hundred students enrolled in one hundred different courses.Footnote 68 In championing the new state extension system in 1916, its director James Moyer claimed that it surpassed the benefits of a centralized state university because students did not need to pay for room and board, and could take courses part-time while still working. In his words, it “provides everything the advocates of a State University for Massachusetts have in mind.”Footnote 69

Others disagreed. At an annual conference at the State House, Reverend Berle angrily stated that “the recent legislation on university extension was gotten only by taking the Legislature by the throat. It was a substitution for a provision for a State university, which has been and is being agitated.”Footnote 70 Berle, who had himself attended Harvard Divinity School and sent his son to Harvard College, claimed that as a “Harvard man” he saw how undemocratic and “entirely out of sympathy with the requirements of its community” the institution was. Observing the obstacles faced by working-class students at Harvard had “convinced me that we need a State University . . . [reaching] every young person in the State who shows any disposition to its benefits.”Footnote 71 Berle was part of a milieu of progressive reformers including Jane Addams and Louis Brandeis who had faith in the transformative power of education and resisted the corrupting forces of private monopoly on politics.Footnote 72 Berle claimed there was “general distrust” of the State Board of Education because it was seen as “the instrument of the [private] higher institutions for learning in this State,” evidenced by the recent “grabbing by the Institute of Technology of $1,000,000 of the State's money.”Footnote 73 Berle's assessment of the cozy relationship between private universities and the state board seemed to be confirmed by the next commissioner of education, Payson Smith, who favored private higher education provision. As Smith argued in 1918, “if the endowed colleges of the country perform the functions of a public service corporation and care for the needs of the people as the times require . . . there need be no State Universities.”Footnote 74

World War I, Selective Enrollment, and Junior College Proposals, 1915–1934

The years around World War I witnessed renewed pressure for a state university. The Massachusetts branch of the AFL, which gained strength in a wartime economy, brought forward repeated petitions for a state university in Boston.Footnote 75 These years also witnessed the creation of the first AFL teachers’ union in Boston, albeit short-lived from 1919 to 1925, as well as the Boston Trade Union College (BTUC) that operated between 1919 and the Great Depression. The repeated setbacks to public higher education likely contributed to the decision of Boston's labor unions to take matters into their own hands and launch their own college. The BTUC was part of a wave of labor colleges that emerged after World War I and offered a wide range of evening courses, with curricular decisions decided on democratically, to workers and their families in public school buildings. While catering primarily to labor activists and never a mass institution, BTUC offered an alternative to Boston's landscape of private colleges and universities.Footnote 76

The anti-labor backlash of the first Red Scare posed new obstacles and shaped the language in which opponents rejected public higher education. In 1915, the principal of a private preparatory school, George Fox, claimed that a state university would be “a case of dead-beat Socialism . . . because it places all the expense on the State treasury.” Positioning himself as a true champion of working people, he argued that a state university would be a “robbery of the working class taxpayers” who would be forced to pay for a university that most would not attend.Footnote 77

At a time of heightened nationalism, some public officials came to support a state university for its potential to cultivate democratic citizenship. State Board of Education member Clarence Kingsley argued in 1923 that a “state university would be a unifying force in the community which is . . . increasingly needed to bring out common ideas and common ideals necessary that Democratic society may function and survive.”Footnote 78 At the height of anti-immigrant sentiment, many policymakers viewed education as strategy to assimilate immigrants and stem the radicalism associated with foreigners. In addition to Americanization courses introduced into public schools, the state extension department launched an Americanization campaign through English language and civics courses.Footnote 79 Some public officials, like Boston superintendent of schools Frank Thompson, rejected xenophobic “100% Americanism” and stressed the role of public schools in promoting the best democratic values of the United States.Footnote 80 In his 1919 annual report, he argued that Massachusetts was falling behind western states that had already made college a guaranteed “democratic right” for all young people, and that “the day has come in Massachusetts” for a free university in Boston.Footnote 81

Legislatively, World War I brought new regulations concerning state aid to private institutions. The 1917–1918 Massachusetts constitutional convention extended the reach of the 1853 anti-aid amendment to higher education for the first time. In the debate over its passage, it was revealed that since 1860, the state had spent nearly $8 million on private colleges and universities, largely in the form of scholarships. The 1918 amendment represented a new wartime skepticism of private institutions and a commitment to expanding public services and oversight.Footnote 82

The debate over a public university was also reshaped by the educational and economic landscape in the 1920s. Namely, a high school boom was putting more enrollment pressure on private colleges and universities than they could, or wanted to, accommodate. Since 1890, the number of students enrolled in public high school in Massachusetts had quadrupled, and an increasing percentage of them sought higher education, most entering a rapidly growing sector of white-collar and professional employment.Footnote 83 This was especially pronounced among women students, whose enrollment in higher education was now increasing at a pace twice as fast as men's enrollment.Footnote 84 By 1924, Massachusetts ranked first among states in the number of students attending colleges and universities, especially at Boston's large urban universities, Northeastern University (recently incorporated with general degree-granting power) and BU. However, half of Massachusetts college students were from out-of-state, and Massachusetts ranked twenty-fifth in the percentage of its own high school graduates who went on to college.Footnote 85 Many commentators criticized the limited number of spots available to local graduates. In 1921, the Boston Globe editors wrote: “Thousands of [young people] are reaching out for higher education [but] all of our privately endowed colleges are full to bursting.”Footnote 86 Based on a 1922 survey, colleges including Wellesley, Simmons, and Worcester Polytechnic Institute all described needing to curtail student admissions because of the limited capacity of their classrooms and dormitories.Footnote 87

The exclusion of students by private institutions was made even more visible by changes in formal admissions policies.Footnote 88 Before 1920, colleges tended to be more concerned with attracting enough enrollment than barring students from attending. Most colleges in Massachusetts, including BU, BC, Tufts, and MAC, admitted students on the high school certificate system, granting admission to graduates of approved high schools. At more elite colleges including Harvard, MIT, Wellesley, and Smith College, the majority of students gained admission through subject-based entrance examinations.Footnote 89 For many colleges in the nineteenth century, these exams included Latin and Greek, not offered in all public high schools. The desire to attract enrollment as well as forge relationships to local public school systems led colleges like Harvard to modernize their entrance requirements and eliminate the classical language requirement at the turn of the twentieth century. In addition, students who did not pass the entrance exams could still be admitted with “conditions,” expanding enrollment further. In 1922, 14 percent of Harvard students and 42 percent of MIT students were admitted with conditions.Footnote 90

More flexible entrance examinations, combined with the high school graduation surge, however, began to change student demographics. Elite institutions like Harvard were especially concerned by the growing number of Jewish students, who grew from 1 percent of the student body in 1881 to 20 percent by 1922. President Lowell attempted to implement a 15 percent Jewish admissions cap, but when this blatant form of discrimination failed, he led changes to admissions criteria to include selection based on “character and fitness,” a photograph of the student, and questions about religion and ethnicity.Footnote 91 University administrators were careful to denounce racial and religious discrimination in public statements, but the anti-Semitism of many private-college leaders was not a secret, and Harvard's new admissions policies had the effect of capping the enrollment of Jewish students.Footnote 92

Several Boston Rabbis became outspoken champions of a state university as an alternative to what they believed to be prejudiced admissions practices. In 1922, Rabbi Harry Levi of Temple Israel rejected new proposals for “restriction on racial and religious grounds,” as well as the use of psychological tests in vogue in the early 1920s, which “camouflage means of shutting out those not socially eligible.” He concluded, “Let us have a State university and have it as soon as possible.”Footnote 93

In debates over college admission policies, many private-college and university administrators defended the selective function long performed by private higher education. President Alexander Meiklejohn of Amherst College defended the right of universities to exclude high school graduates and claimed it would be an “unmitigated nuisance” if universities “had to provide for students who don't at present meet demands made upon them.”Footnote 94 In 1922, the dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Henry Holmes, stated that “colleges are not in duty bound to educate everybody. . . . Selection is inevitable and the main duty of every institution of higher education is to maintain its standards with rigor and fairness.”Footnote 95

Several public officials, however, disagreed with this assessment. Superintendent Thompson described how the “overcrowded conditions in the various colleges” led them to “make their requirements so stiff” that only half of public school graduates could get in. This restriction, he argued, “is not fair. . . . This is not truly representative of the whole people and it is not democratic.”Footnote 96 State Board of Education member Kingsley further argued against entrance requirements that forced students to “study subjects which are not of real use to them.”Footnote 97 A state university, he argued, would allow students to pursue the kinds of subjects they desired. Furthermore, between 1915 and 1924, the average tuition of liberal arts colleges in Massachusetts rose by 64 percent. According to a 1922 survey of public-school administrators in Massachusetts, roughly two-thirds believed that tuition rates and entrance requirements each significantly reduced the number of qualified high school graduates who could attend college.Footnote 98

Controversies over admissions policies did not lead to the creation of a public university, but they did spawn innovations compatible with existing private institutions. In response to a 1921 AFL petition, another state commission was appointed to investigate higher education, chaired by the president of BU, Lemuel Murlin.Footnote 99 The final 1923 report was unanimous in rejecting a state university, arguing that current colleges were “not so crowded as has been reported,” that admissions requirements were “not so severe as commonly believed,” and that the needs of higher education “can be met most economically and efficiently” through existing private institutions. Instead, the commission proposed a decentralized system of free junior colleges offering the first two years of college instruction. The model proposed by the commission shared aspects of the 1895 and 1912 proposals: multiple “centers” would launch college courses within existing public school buildings, greatly reducing expenses, and offer not only arts and science courses, but a wide range of technical and practical subjects. They would offer equal opportunity to women students, unlike the predominantly men's colleges in the Boston area (with the exception of Radcliffe, Wellesley, Simmons, and co-ed BU). A system of twelve junior colleges was estimated to cost between $125,000 and $250,000 annually, compared with the cost of a single state university, estimated at $10-$12 million upfront and $1-$2 million annually. Most of Boston's private universities were less threatened by a two-year institution that did not compete with four-year collegiate instruction. However, some private colleges still opposed the proposal: the president of BC, a college which catered to lower-middle-class Catholics, argued in a minority report that junior colleges were unnecessary and existing institutions could satisfy the demand for college education.Footnote 100

While the state investigation was underway, the Boston School Committee also explored the possibility of establishing a municipal junior college. By 1924, the Boston Normal School had become Boston Teachers College, and was granted the power to offer a bachelor of education and bachelor of science in education (although still not the bachelor of arts, reserved for the traditional liberal arts colleges).Footnote 101 In a 1925 report, the Boston School Committee suggested that the Teachers College, as the only public degree-granting institution in the city, could become “the nucleus for a municipal university.” However, as a first step in expanding municipal higher education, it recommended the preliminary establishment of an independent two-year junior college.Footnote 102

In the years that followed, however, neither the state nor the city of Boston acted on the junior college recommendations.Footnote 103 Rather, the private sector jumped into this new educational market. In the early 1930s, several private institutions successfully petitioned the state legislature to change their status to that of junior colleges, including Lasell Seminary, a women's seminary in nearby Newton, and Portia Law School in Boston, originally founded in 1908 as the first women-only law school in the country.Footnote 104 These private junior colleges overwhelmingly catered to women students, demonstrating unmet demand: by 1940, the Boston area was home to seven private junior colleges enrolling nearly one thousand students, 95 percent of them women.Footnote 105

Student enrollment pressure also instigated new efforts to convert MAC into a public state university, although these attempts stalled through the 1920s. Despite its geographical distance from major population centers, MAC was an obvious locus for building a state university. Until 1926, tuition was effectively free to in-state students (although students were charged small fees).Footnote 106 In addition, by 1929, 90 percent of MAC students did not actually pursue agriculture, but rather pursued diverse specializations in the arts and sciences. Multiple constituencies, however, opposed turning MAC into a state university: older alumni who were farmers or agricultural scientists that took pride in the agricultural focus of their alma mater, organized labor that favored a university in the industrial center of Boston, and, most importantly, private institutions and their state allies.Footnote 107 The 1923 report urged MAC to double down on its agricultural focus, pointing to the decline of food production in the state.Footnote 108 Left unsaid was that this focus limited its competition with private colleges represented by the reports’ authors. Finally, in 1931, in response to growing student and alumni pressure, the Massachusetts governor signed a bill changing the name of the institution from Massachusetts Agricultural College to Massachusetts State College (MSC), acknowledging the reality of its broad scope.Footnote 109 MSC, however, remained a small institution at just over one thousand students in 1934 (compared to the forty-one thousand total private college and university students in the state) and geographically removed from the site of highest student demand.Footnote 110

World War II, Community Colleges, and the University of Massachusetts, 1947–1970

The enormous post-WWII enrollment surge, driven first by veterans and then the baby boom, brought about a new era in public higher education in the United States, and significant milestones in the state of Massachusetts. For the first time in 1947, a state-commissioned report on the needs of higher education was conducted with minimal private university representation, and that year, MSC became the University of Massachusetts (UMass), the first public university in the state. In the 1960s, a network of public junior colleges (or community colleges) was established, and a branch of the University of Massachusetts was founded in Boston in 1965. A new political and economic landscape helped bring about these changes. Democrats, the longtime ally of organized labor in the state, had gained control of both the state House and Senate in 1958, establishing effective one-party rule by the mid-1960s. Boston-area working-class Catholics began attending college in greater numbers, and new suburban residents, many with ties to the growing tech enterprises along Route 128, became a significant constituency of the Democratic Party and also supported the expansion of public higher education. Overall, state expenditure on public higher education grew from 4 percent of total expenditure in 1960 to 7 percent by the early 1970s. The new $350 million Boston campus was the largest public construction project in the history of the state. Although total enrollment in public higher education remained lower than private enrollment, it grew from 10 percent of Massachusetts students in 1940 to over 40 percent by 1980 (see Figure 2).Footnote 111

Figure 2. Total Enrollment in Massachusetts Higher Education, Private and Public, 1910–1990. Data includes both two- and four-year institutions. Sources: Report of the Commissioner of Education, 1911, Vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1912); Biennial Survey of Education, 1918–1950 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1923–1954); Digest of Educational Statistics, 1962–1992 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1962–1992).

The expansion of public higher education in this era, however, was not a reversal of prior power dynamics between the public and private sector, but rather a reflection of a reconfigured institutional landscape. In a time of enrollment expansion, most of Boston's private institutions shifted away from serving local commuter students and toward more affluent, academically competitive, and out-of-state students. Private universities also found new ways to benefit from the expansion of public educational funding at both the federal and state level. Federal financial aid for veterans and working-class students subsidized private institutions, and research universities like Harvard and MIT garnered enormous federal grants for scientific research. At the state level, private universities successfully lobbied the Massachusetts legislature for expanded aid to private institutions.Footnote 112 Public institutions, in turn, faced financial or capacity limits that kept free public higher education for all an elusive goal. Most adopted private university practices, such as charging higher student tuition and fees and selective admissions policies. By the early 1970s, when the period of abundant state funding came to an end, Massachusetts was home to a more expansive educational landscape but private institutions remained at the top of the educational hierarchy.

The surge of enrollment from veterans immediately after the war confirmed the need for a larger state university. MSC believed it was better to claim this institutional status for itself than lose out to a site in greater Boston, where nearly 50 percent of state residents lived by 1940.Footnote 113 In 1947, the state legislature authorized MSC to change its name to the University of Massachusetts, and made appropriations for the expansion of its collegiate and graduate arts and science programs, which included the addition of engineering, physics, home economics, education, nursing, and business administration. Additional faculty, facilities, and dormitories allowed enrollment to grow from twenty-seven hundred to thirty-five hundred students. However, in contrast to the strategy of urban universities like Northeastern to expand pre-professional programs that catered to part-time commuter students, UMass administrators were more interested in pursuing selective enrollment and building the academic profile of their arts and science departments.Footnote 114 Tuition for in-state students had been introduced in 1926 and rose in subsequent decades.Footnote 115 Ultimately, this agenda continued to leave many working-class Bostonians without access to public higher education.

Between 1948 and 1960, pressure for a community college network continued to build. A 1948 legislative report, recalling the 1923 junior college plan, recommended establishing two-year junior colleges within existing state teachers colleges.Footnote 116 At this time, there were ten state teachers colleges in Massachusetts, originally founded as state Normal Schools that had become “teachers colleges” offering education degrees in 1932.Footnote 117 (These did not include Boston's teachers college, a municipal institution). State teachers colleges had introduced in-state student tuition in 1924, albeit with rates lower than UMass.Footnote 118 Although the state authorized the creation of community colleges in 1948, either within existing state teachers colleges or as new entities through the local funding of school committees, in the next ten years only Newton launched a municipal community college housed within Newton High School.Footnote 119 In 1958, public higher education found a new advocate in Democratic Massachusetts governor Foster Furcolo. In the wake of a 1957 report ranking Massachusetts last in the nation for the percentage of the state budget spent on higher education, Furcolo argued that expanding public higher education was an “emergency,” and proposed a plan of nine newly constructed regional junior colleges.Footnote 120 In September of 1960, Berkshire Community College, the first two-year public junior college in Massachusetts, was opened in Pittsfield in a repurposed high school building to 125 students. Annual tuition was about the same as the price tag of UMass in-state tuition at the time: $200.Footnote 121 The following year, three more community colleges were opened, including the first in Boston: Massachusetts Bay Community College (MBCC) in the Back Bay, charging $300 in annual tuition to seven hundred students. By 1964, seven community colleges dotted the state.Footnote 122

These new community colleges were still far from sufficient in meeting enrollment demands. By 1964, MBCC was projected to need up to five thousand additional spots—over six times its current capacity—to meet demand in Boston. The chairman of the Regional Community College Board, Kermit Morrissey, noted that Boston was “getting such a pressure of applicants (fourteen hundred for four hundred spots last year) that [MBCC] is getting as selective as a good four-year college.” In 1964, 70 percent of MBCC students came from outside Boston itself, mostly from wealthier Boston suburbs. Officials like Morrisey urged the expansion of new community colleges in the greater Boston area to make space for local, working-class residents.Footnote 123

By this time, Boston was also home to another institution of public higher education: Boston State College, the restructured Boston Teachers College. In 1952, the Boston School Committee decided to transfer control of its municipal teachers college to the state as a way to save the city significant expenses.Footnote 124 In 1959, under pressure to serve broader populations seeking higher education in the arts and sciences, the Massachusetts legislature granted all state teachers colleges the ability to grant liberal arts degrees, and a subsequent 1960 act changed the names of all “State Teachers Colleges” to “State Colleges” to better reflect this broader scope. Boston State College became the first public college in Boston with the authority to grant bachelor of arts degrees.Footnote 125 By 1963, it enrolled twenty-eight hundred students in downtown Boston.Footnote 126

Boston's private colleges viewed the expansion of public higher education with suspicion, but their own changing student demographics diminished their opposition. In 1950, the Boston Globe could write that the junior college movement in Massachusetts had “no better friend” than Harvard president James Conant, who offered to make Harvard facilities available to train the teachers and administrators for new public junior colleges. As Conant argued, “For many types of students, a terminal two-year education beyond high school, provided locally, seems better adapted to their needs than that offered by a traditional four-year residential college.” Public junior colleges, thus, would not threaten elite private colleges.Footnote 127 Tuition-driven universities like BU and BC may have had more reason to be concerned: BU had launched its own two-year “General College” program in 1952 to cater to WWII veterans and take advantage of federal funding.Footnote 128 But as postwar enrollments grew, these institutions focused on pursuing strategies of elite institutions: higher tuition, selective enrollment, a national student body, and graduate programs in the arts and sciences. At BU, between 1952 and 1967 annual tuition rose from $550 to $1,250, and the percentage of in-state students dropped from 80 percent to 35 percent. By 1967, BC, which traditionally had been the cheapest college in the Boston area, was charging higher tuition than BU (see Figure 1) and increasingly catered to more affluent Catholics from beyond Massachusetts.Footnote 129

Northeastern University was the one exception to this trend. Although it had implemented tuition hikes, new dormitories, and increased research capacity, its primary institutional strategy was to expand its cooperative and part-time courses that catered to working-class commuters who were older than typical students. Northeastern grew from twenty thousand students in 1959 to forty-five thousand by 1967, becoming the largest private university in the United States. With the cheapest tuition in the Boston area, it was described by a 1973 Carnegie Commission on Higher Education report as “a private university serving the urban proletariat.”Footnote 130 Not surprisingly, Northeastern remained uniquely hostile to public higher education in the city.Footnote 131

The new political alignment of Boston's private and public institutions was visible in the debate surrounding the opening of a University of Massachusetts in Boston. UMass Amherst had grown to seventy-seven hundred students by 1963, but had simultaneously become more selective and catered to wealthier students from Boston's suburbs.Footnote 132 Many local and state officials recommended Boston State College as the center of a new university in Boston, independent from UMass Amherst. The state college system was underfunded compared with UMass, which was a source of resentment between the two state systems.Footnote 133 In addition, as an outgrowth of the municipal teachers college, Boston State College was seen by many Bostonians as the natural center of a public university. In 1963, Senate president John Powers from Boston sought to turn BSC into a “commuter university of the future” serving twenty thousand students.Footnote 134 The president and trustees of UMass Amherst, however, opposed these proposals, and moved quickly to ensure that any new university campus would be under their control. Their allies in the State House introduced legislation in the spring of 1964 to establish a branch of UMass in Boston, known as “Hub UMass.”Footnote 135

Northeastern president Asa Knowles led the opposition. He was angered by the move and claimed there had been an unwritten agreement that a public university would not be built in Boston.Footnote 136 The president of BU also registered opposition, arguing that the proposal was “premature” and needed “intense study.” Also opposed was the director of the state college system, John Gillespie, who argued that the bill was “woefully inadequate” and “hastily conceived.”Footnote 137 Other private college leaders, however, like BC president Michael Walsh, favored the establishment of UMass Boston, which he thought would cater to working-class Catholics who no longer had access to his own school and who sought opportunities outside of the traditionally Protestant private universities.Footnote 138

Despite the opposition, the Democrat-dominated state legislature in the 1960s was strongly supportive of expanding public higher education, and western Massachusetts representatives lent their support, seeking to strengthen the UMass system with UMass Amherst as its flagship.Footnote 139 The legislature approved the plan in June 1964, providing “urgently needed facilities for students residing in or near the city of Boston.”Footnote 140 Housed in the former Boston Gas Company building in the city's downtown, UMass Boston opened to twelve hundred students in September of 1965; it charged $200 in annual tuition.Footnote 141 The core members of the faculty were recruited from UMass Amherst, attracting those eager to contribute to the new university's mission and relocate to the Boston area.Footnote 142 Several aspects of the new UMass campus likely reassured its opponents, however. The new university offered a four-year liberal arts program, in contrast to Northeastern's signature part-time cooperative and occupational programs. Private administrators were also likely relieved by the choice of a new campus site in 1968. Despite support among students and staff for a central “core city” campus, the trustees, facing pressure from the state legislature and the need for a site large enough to accommodate many thousands of students, chose Columbia Point, a large 100-acre landfill and sewage treatment facility on the southern edge of the city, next to Boston's largest public housing project. The site was a mile from the closest subway station, which frustrated many commuting students who preferred a more accessible location.Footnote 143

Private institutions also benefited from a windfall of public assistance in the 1960s. In 1956, Massachusetts legislators pioneered the first state-backed student loan agency, the Massachusetts Higher Education Assistance Corporation, which guaranteed favorable loans to Bay State residents attending either private or public institutions.Footnote 144 Although the anti-aid amendment remained on the books, private institutions found new ways of circumventing it. In 1954, a special legislative commission headed by Senator George Evans, a Wakefield shoe manufacturer, reported that legally, the anti-aid amendment prevented direct subsidies of higher education, but it did not prevent a state board from receiving state funds and then contracting with private institutions for their services.Footnote 145 In the years that followed, administrative boards were used to massively expand state scholarships to private institutions.Footnote 146 Tuition-driven institutions like BC, BU, and Northeastern made securing state scholarships their top priority, and their powerful new lobbying group, the Association of Independent Colleges and Universities in Massachusetts (AICUM), founded in 1967, worked closely with the new state Board of Higher Education. Between 1960 and 1974, the annual appropriation for state scholarships grew from $100,000 to a whopping $9.5 million. Three-quarters of these funds went to students attending private colleges and universities.Footnote 147

Austerity Politics, 1970–1982

By the early 1970s, the academic “golden age” had come to an end. In response to slowed economic growth, federal aid was reduced and both Republican and Democratic state governors recommended their legislatures freeze spending increases for public higher education. Public support was also waning in the wake of the tumultuous student protests and battles over desegregation, and student demand lessened as the enrollment boom slowed. Private colleges, facing their own budget shortfalls, became more hostile to the expansion of the public sector. The new conditions of austerity led state actors to return to their traditional cooperative relationship with private higher education.Footnote 148

Key state officials were strong allies of private universities in the 1970s. The new state secretary of administration and finance, William Cowin, openly admitted he had “a personal bias toward the privates,” and did not believe that the state legislature was taking sufficient advantage of their services. Recalling the arguments of state reports dating back to 1912, he argued that public educational expansion was unnecessary and more cost-effective measures included granting public funds to private institutions and leasing space from private colleges instead of purchasing additional facilities.Footnote 149 The move to privatize public services is often associated with the neoliberal era, but in the context of Massachusetts higher education, it represented a return to long-standing educational practices.

Massachusetts state and educational officials also pursued practices typical of the private sector that seemed to betray the century-long demand for a free public university. Specifically, they began to shift the financing of higher education onto students through higher tuition. A chief demand of AICUM was raising public tuition to “equalize competition” between public and private universities. The President of UMass Robert C. Wood, seeking cooperation with the private sector, began to advocate for public tuition increases in the 1970s.Footnote 150 In 1979 the state education secretary mandated that all state colleges and universities raise tuitions to compensate for state budget restrictions. Annual tuition at UMass rose from $300 in 1971 to $750 in 1981.Footnote 151 The shifting burden from public funding to student tuition was not unique to Massachusetts in these years but adopted across the country, even in states with some of the most developed systems of public higher education, reflecting a conservative turn to austerity politics. Although California wrote into its 1868 state constitution that, finances permitting, no tuition should be charged to in-state University of California students, it introduced tuition in 1970. That year, combined in-state tuition and fees at UC were roughly the same as tuition at UMass Amherst.Footnote 152

A restructuring of Boston's public higher education landscape in the early 1980s also pushed tuition higher and reduced the number of seats in the city's public degree-granting institutions. In 1981, Boston State College was absorbed into UMass Boston.Footnote 153 In the new budgetary climate of the mid-1970s, advocates of a Boston State-UMass merger cited the need to address enrollment decline and avoid costly duplication of programs.Footnote 154 Opponents of the merger, like Secretary of Educational Affairs Paul Parks, argued that the elimination of the state college would end up raising admissions requirements and tuition costs to the level of the UMass system (higher than the existing state college system), effectively shutting out large numbers of working-class students.Footnote 155 Opposition among students and staff grew in 1981 when the Massachusetts Board of Regents released the details of the merger plan, which, in response to a $6 million state budget shortfall, was slated to occur in a matter of weeks and entail laying off nearly four hundred part-time and full-time faculty.Footnote 156 In response to protests and legal action, the merger and layoffs were postponed by a few months, but not abandoned. In January of 1982, former Boston State students began their spring semester as UMass Boston students, with only a fraction of their former faculty rehired at the state university.Footnote 157 The new UMass Boston had twenty-five hundred fewer spots than the combined enrollment of the two former institutions. By 1982, annual tuition had risen to $1,100.Footnote 158 Rising student costs, fewer seats, and reduced funding for public higher education once again favored the position of private colleges and universities in the state.

Conclusion

The long struggle for a public university in Boston can offer historians several insights. This fight reveals the extent to which private versus public competition was a crucial dynamic in shaping the development of higher education. Although Massachusetts's earliest colleges were “quasi-public,” by the late nineteenth century, these colleges closely guarded degree-granting power for themselves and mobilized against free, publicly funded higher education championed by organized labor, public school teachers, and local politicians. A repeated refrain from private university leaders and politicians with ties to these institutions, drawing on the tradition of public-serving corporations, was that existing private institutions could better serve public needs. Through their lobbying efforts and alliances with state officials, private school representatives served on state commissions that authored numerous reports, repeatedly rejecting proposals for a state university. When they did offer recommendations for expanding public resources that were devoted to higher education, they preferred solutions that channeled public dollars to private institutions, or solutions that partnered with or supplemented, but did not compete directly with, existing private colleges and universities. In this way, even in the 1960s when, at long last, public higher education in Massachusetts expanded dramatically, its outer boundaries and internal features were shaped by the competitive landscape of higher education produced by private institutions and their allies.

The specific nature of proposed public-private partnerships set early precedents for many contemporary practices in today's era of austerity budget cuts, the neoliberal faith in the private sector, and skepticism about the competence of government. These include using public funding to pay for private tuition, foreshadowing the expansion of school vouchers and federal financial aid. Partnerships between local school committees and private institutions for teacher training laid the early foundations for the subsequent, outsized role of private universities and private training programs in the professional training of public school teachers. In addition to tuition subsidies, many early state proposals offered up the use of public facilities to private boards or companies, presaging the practice of devoting public funds to private enterprises, such as charter schools. These early reports also proposed the use of public facilities for extension and correspondence courses. While the role of distance learning programs, MOOCs, and other forms of online education are often framed as cutting-edge innovations, distance learning programs via correspondence date back to the early twentieth century.Footnote 159 Finally, even the labor cost-saving practices adopted in early public-private partnerships foreshadow recent trends. Hiring part-time instructors to teach one-off courses bears resemblance to the contemporary casualization of the professoriate by relying on adjuncts with little job security.Footnote 160

We also gain insight into how key innovations in the American educational landscape—financial aid, university extension, and even community colleges—emerged in Massachusetts as compromises to keep the public sector limited. Rather than stand-alone proposals to promote access and opportunity, most of these experiments in Massachusetts were first proposed in reports intended to debunk arguments for a public university, as alternatives that were cheaper and did not overlap with private-sector provision. Although historically these innovations did extend many opportunities to students not well served by existing institutions, their origin as “substitutes” achieved by, in the words of Reverend Berle, “taking the Legislature by the throat,” points to their more complicated legacy in the politics of higher education.

This history also reveals the consistent power of the private sector to garner public benefits, through times of both fiscal abundance and fiscal retrenchment. Public higher education did expand dramatically in the post-WWII period, in Massachusetts as well as across the country. However, even during this era, private institutions were well served by public funding at the state and federal level, receiving large grants and student aid. Today, despite a powerful neoliberal ideology that celebrates the private sector and eschews government spending, private institutions continue to rely on government funding and tax exemptions.

The history of public-private competition can therefore also illuminate the broader significance of private higher education in the United States. In a comparative perspective, the United States is characterized by a “partially private” model of higher education that features high private enrollment and high rates of private financing.Footnote 161 The historical power of private institutions, which shaped the competitive terrain on which higher education developed, helps us understand the origin of this mixed public-private model. It also helps explain the limited growth of free, public higher education in the US and the extraordinarily high cost of education, even at “public” institutions. In this regard, the failure of Massachusetts to offer free college is a history shared with other states, as financing through student tuition and fees became a common feature of public higher education across the country. The long history of public support for private institutions and public-private partnerships in Massachusetts is particularly helpful in understanding the patterns of privatization that have intensified nationwide in recent decades.

Finally, this history reveals the organized interests that have championed the expansion of free public higher education for well over a century, and what they have been up against. In Massachusetts, notably, organized labor played a primary role in this fight, as did public officials eager to respond to growing educational demands among working- and middle-class constituencies. Today, at a time of invigorated campaigns for college for all, the cancellation of student debt, and labor organizing among academic workers, the history of prior efforts to fund public higher education can help us reassess what it will take to make higher education in the United States a free and truly public good.

Cristina Groeger is an assistant professor of history at Lake Forest College and author of The Education Trap: Schools and the Remaking of Inequality in Boston (Harvard University Press, 2021). She thanks Jackie Blount, Ethan Ris, Rudi Batzell, Noah Rosenblum, and HEQ's editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback on this article, and Lena V. Groeger for designing the two graphs.