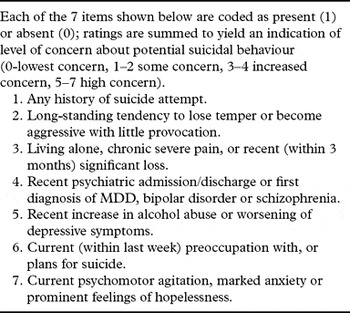

High suicide rates are observed in elderly men, and the identification of high risk individuals is a challenging task. The Suicide Assessment Dimension (see Box 1) is intended to aid the evaluation process. We are concerned that the proposed assessment may miss some seniors in need of intensive management.

Box 1. Proposed DSM-5 Suicide Assessment Dimension

Consider the case of Mr. D, an 80-year-old widower and retired policeman who lives with his son and daughter-in-law. He receives treatment for diabetes, hypertension, and coronary heart disease. There is a past history of alcohol abuse, but Mr. D has abstained since his first stroke five years ago. The hemiparesis improved after a short period of rehabilitation, and Mr. D was once again able to enjoy his favorite pastimes of hunting and fishing. Last year, Mr. D lost his wife of 53 years. He was never one to talk about feelings, but found consolation during fishing trips with his long-time buddies. Six months after his wife's death, Mr. D suffered a second stroke. This one left him wheelchair-bound. He did not do well in rehabilitation this time, and often found excuses not to attend.

Mr. D's son has arranged today's consultation. His father, who was always a “doer”, now spends his days in front of the TV. On several occasions, the family has made arrangements for wheelchair transport so that Mr. D can join in on outings, but he opts to stay at home. They ask if his loss of interest might be a sign of dementia, and if medication will alleviate the condition. Upon examination, Mr. D is lucid. His performance on a battery of cognitive tests is within the normal range. He does not appear depressed, and is able to laugh, but his tone is somewhat sarcastic. There is no psychomotor slowing, and no psychotic thought content. Upon direct questioning, Mr. D denies feelings of depression and suicidal ideation, but complains that life has pretty much lost its meaning. Mr. D abhors the fact that he is dependent on his daughter-in-law for assistance with dressing and personal hygiene.

Mr. D does not fulfil criteria for major depressive episode, but he displays loss of interest and apathy, yielding one point for “worsening of depressive symptoms” (Item 5). His thought content signals hopelessness (1 point, item 7). The total score (2 points) would not give cause for “increased concern”.

Risk factors for suicide in this age group differ somewhat from those of young and middle-aged persons. While Item 2 (long-standing tendency to lose temper or become aggressive with little provocation) is highly relevant when it comes to younger suicides, personality features that infer risk for suicide may alter or attenuate with age. A recent large psychological autopsy showed an inverse relationship between impulsive aggression and age (McGirr et al., 2004). However, increasing levels of harm avoidance were observed with increasing age among suicide decedents in that study. Further, low openness to experience has been associated with death by suicide in later life (Duberstein et al., Reference Duberstein, Conwell and Caine1994). We therefore propose that Item 2 could include also rigid personality style.

Item 3 (living alone, chronic severe pain, or recent (within 3 months) significant loss) begs comment from a late-life perspective. Many seniors live alone, but few die by suicide. Lack of social support (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison2010) would constitute a more compelling signal of increased risk for suicidal behavior in this age group. Further, the three-month specifier for significant loss seems short. Complicated grief, which is diagnosed after six months or more, has been shown to be related to suicidality (Szanto et al., Reference Szanto2006). Risk may be systematically underrated in seniors as Item 3 factors are more likely to co-exist and interact in later life.

Older persons with severe physical illness/functional disability are more likely to commit suicide than their healthier peers (Waern et al., Reference Waern, Rubenowitz, Runeson, Skoog, Wilhelmson and Allebeck2002). Serious health problems can lead to loss of autonomy; individuals may feel that they are a burden on others. A separate rating for “serious physical health issues” (chronic severe pain/severe physical illness/disability) might enhance the utility of the Suicide Assessment Dimension for the elderly, a vulnerable and fast-growing age group.

Note: The case is a composite based on a psychological autopsy study of suicides that occurred in late life (Waern et al., Reference Waern, Rubenowitz, Runeson, Skoog, Wilhelmson and Allebeck2002).