Evidence on the short- and long-term beneficial effects of breast-feeding continues to increase(Reference Ip, Chung and Raman1, 2) and exclusive breast-feeding is recommended for the first 6 months of life(3, 4). However, breast-feeding rates in maternity units vary strongly from country to country, and the level in France at the turn of this century was particularly low (63 %)(Reference Zeitlin and Mohangoo5). National rates mask important regional differences, as observed in the UK(Reference Hamlyn, Brooker and Oleinikova6, Reference Bolling, Grant and Hamlyn7), Italy(Reference Giovannini, Banderali and Radaelli8), the USA(Reference Singh, Kogan and Dee9, Reference Li, Darling and Maurice10), Australia(Reference Donath and Amir11) and France(Reference Rumeau-Rouquette, Crost and Breart12, Reference Blondel, Supernant and du Mazaubrun13).

Understanding these geographic variations is essential for several reasons. First, public health policies, including breast-feeding promotion policies, are conducted at the level of regions or states within countries(Reference Singh, Kogan and Dee9, Reference Hercberg14). Identification of geographic zones with particularly high or low breast-feeding rates could thus facilitate the orientation of these policies.

Second, analysis of regional differences may contribute to better knowledge of the determinants of breast-feeding. Many factors influence breast-feeding practice and interact at various levels. Besides factors at the individual level, the contextual factors that characterize women’s environments also play an important role – factors such as family, social network and community(Reference Yngve and Sjostrom15, Reference Bentley, Dee and Jensen16).

Nevertheless, we know relatively little about the respective roles of individual and contextual characteristics in breast-feeding and how these characteristics interact at different levels. To our knowledge, few studies have examined the geographic variations of breast-feeding rates within countries, after adjusting for individual factors(Reference Singh, Kogan and Dee9, Reference Ahluwalia, Morrow and Hsia17). Moreover, studies that have assessed the role of contextual characteristics analysed them at the individual (e.g. for newborns) instead of group level (e.g. geographic areas)(Reference Singh, Kogan and Dee9, Reference Dubois and Girard18, Reference Griffiths, Tate and Dezateux19).

Among the entire set of factors that influence breast-feeding practices, social and cultural factors occupy a particularly important place. In high-income countries, breast-feeding is more common among women of higher social class, immigrants(Reference Hamlyn, Brooker and Oleinikova6, Reference Yngve and Sjostrom15, Reference Bonet, Kaminski and Blondel20) and metropolitan residents(Reference Singh, Kogan and Dee9, Reference Dubois and Girard18). Moreover, the decision to breast-feed depends on the attitude of family and friends and on the general opinion of the population about breast-feeding. Public beliefs about breast-feeding vary according to the general population’s economic and cultural level(Reference Li, Ogden and Ballew21, Reference Li, Hsia and Fridinger22). It is therefore important to know the extent to which the social characteristics of women and of the general population may explain some of the regional differences in breast-feeding.

Our objective was to investigate how regional variations in breast-feeding in maternity units might be explained by differences in the distribution of individual maternal characteristics between regions, and whether regional social characteristics were associated with breast-feeding, independently of individual-level factors. We also used empirical Bayes residuals to identify regions with extremely high or low breast-feeding rates, after adjustment for individual-level characteristics. This analysis, which used multi-level models(Reference Raudenbush and Bryk23), was conducted with data from a national representative sample of births in France in 2003.

Materials and methods

Data

Individual-level data were obtained from the most recent French National Perinatal Survey conducted in 2003. The survey’s design has been described in detail elsewhere(Reference Blondel, Supernant and du Mazaubrun13). It included all births in all administrative regions at or after 22 weeks of gestation or newborns weighing at least 500 g during a 1-week period. Two sources of information were used: (i) medical records, to obtain data on delivery and the infant’s condition at birth; and (ii) face-to-face interviews of women after childbirth, to obtain data about social and demographic characteristics and breast-feeding. Approximately 50 % of mothers were interviewed within 48 h of the birth and 38 % on the third or fourth postpartum day. The information regarding infant feeding refers to the feeding method (only breast-fed, breast-fed and bottle-fed, or only bottle-fed) reported by the mother at the interview.

The final study population consisted of 13 186 infants, after the exclusion of infants born in French overseas districts (n 636), infants transferred to another ward or hospital (n 975), infants whose mother was hospitalized in an intensive care unit for more than 24 h (n 26), and those with an unknown feeding status (n 393).

Regional-level data came from the census data from 1999 and 2003. We distinguished twenty-four regions: twenty-one administrative regions and a further subdivision of Ile-de-France: Paris, Petite Couronne (Paris inner suburbs) and Grande Couronne (Paris outer suburbs).

Outcome and predictor variables

We analysed breast-feeding as a binary variable, considering that newborns were breast-fed if they were fed entirely or partly breast milk at the time of the interview.

At the individual level, we included variables identified in a previous analysis as related to breast-feeding in our population(Reference Bonet, Kaminski and Blondel20). Social and demographic variables included maternal age, parity, nationality, maternal occupation (current or last occupation) and partnership status (marital status/living with a partner). Other variables were included in the models as potential confounders: mode of delivery, characteristics of the infants (gestational age, birth weight and multiple birth), status of maternity units (university, other public and private hospitals) and size (number of births per year).

The social context at the regional level was characterized by four indicators: the percentage of urban population (percentage of population in communes that includes an area of at least 2000 inhabitants with no building further than 200 m away from its nearest neighbour), the percentage of residents with a university educational level (percentage of residents aged 15 years old or above with at least a 3-year university degree), the average annual salary per employee (in Euros) and the percentage of non-French residents.

Statistical analysis

We estimated breast-feeding rates by region with corresponding 95 % binomial exact CI. We used a two-level hierarchical logistic regression model(Reference Raudenbush and Bryk23) with infants (level 1) nested within regions (level 2). First, we estimated a random intercept model without any predictor variables (model 1, ‘empty model’) to obtain the baseline regional-level variance (τ 00(1)). In a second model (model 2), we included variables characterizing mothers, infants and maternity units. Model 2 allowed us to estimate the residual regional variation after adjustment for individual-level variables (τ 00(2)). We used the proportional change in the variance (PCV), defined as PCV = (τ 00(1) − τ 00(2)/τ 00(1)) × 100, to assess the extent to which regional differences may be explained by the compositional factors (i.e. possible differences in the distribution of individual-level characteristics) of the regions.

Next, we investigated whether regional variables were associated with breast-feeding independently of individual-level factors. We included regional-level variables in four separate models (model 3a–d), after adjustment for individual-level variables: percentage of urban population (model 3a), percentage of residents with a university-level education (model 3b), average annual salary (model 3c) and percentage of non-French residents (model 3d). Additional analysis allowed us to investigate the effect of the regional characteristics most strongly associated with breast-feeding when put together in the same model (model 4). Cut-off points for regional variables were established at the 50th percentile and the reference category for each variable was equal or inferior to the 50th percentile of the distribution of each variable. Analyses using quartiles showed comparable results.

We also examined whether the effects of certain individual-level social characteristics differed across regions. We did so by estimating random coefficient (random intercept and random slope) models to assess whether associations between breast-feeding and maternal nationality and occupation varied from one region to another. In addition, we tested whether the association between breast-feeding and maternal occupation varied according to the educational level of the population in each region, and whether the association between breast-feeding and maternal nationality varied according to the percentage of the non-French population in each region, by examining cross-level interactions.

Finally, we analysed regional differences in breast-feeding using empirical Bayes residuals, in order to identify outlier regions (those with unusually high or low breast-feeding rates). Empirical Bayes residuals are defined by the deviation of the empirical Bayes estimates of a randomly varying level-1 (individual level) coefficient from its predicted value based on the level-2 (regional level) model(20). We computed empirical Bayes residuals based on a random intercept model that included only individual-level variables. Hence, these residuals reflect differences across regions after adjustment for individual-level characteristics. Computation of the residuals for each region took into account the number of infants in the region. As a result, the fewer the number of infants in a region, the more the value of the regional residual shrinks towards the average breast-feeding rate across regions. This is done so that small regions do not appear as outliers due purely to chance. We compared the ranking of regions for all breast-fed infants (only breast-fed and breast and bottle-fed) and also for infants only breast-fed.

Descriptive analysis was performed using the STATA statistical software package version 9·0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Multi-level analysis was performed using hierarchical linear and non-linear modelling (HLM version 6) software (Scientific Software International Inc., Lincolnwood, IL, USA).

Results

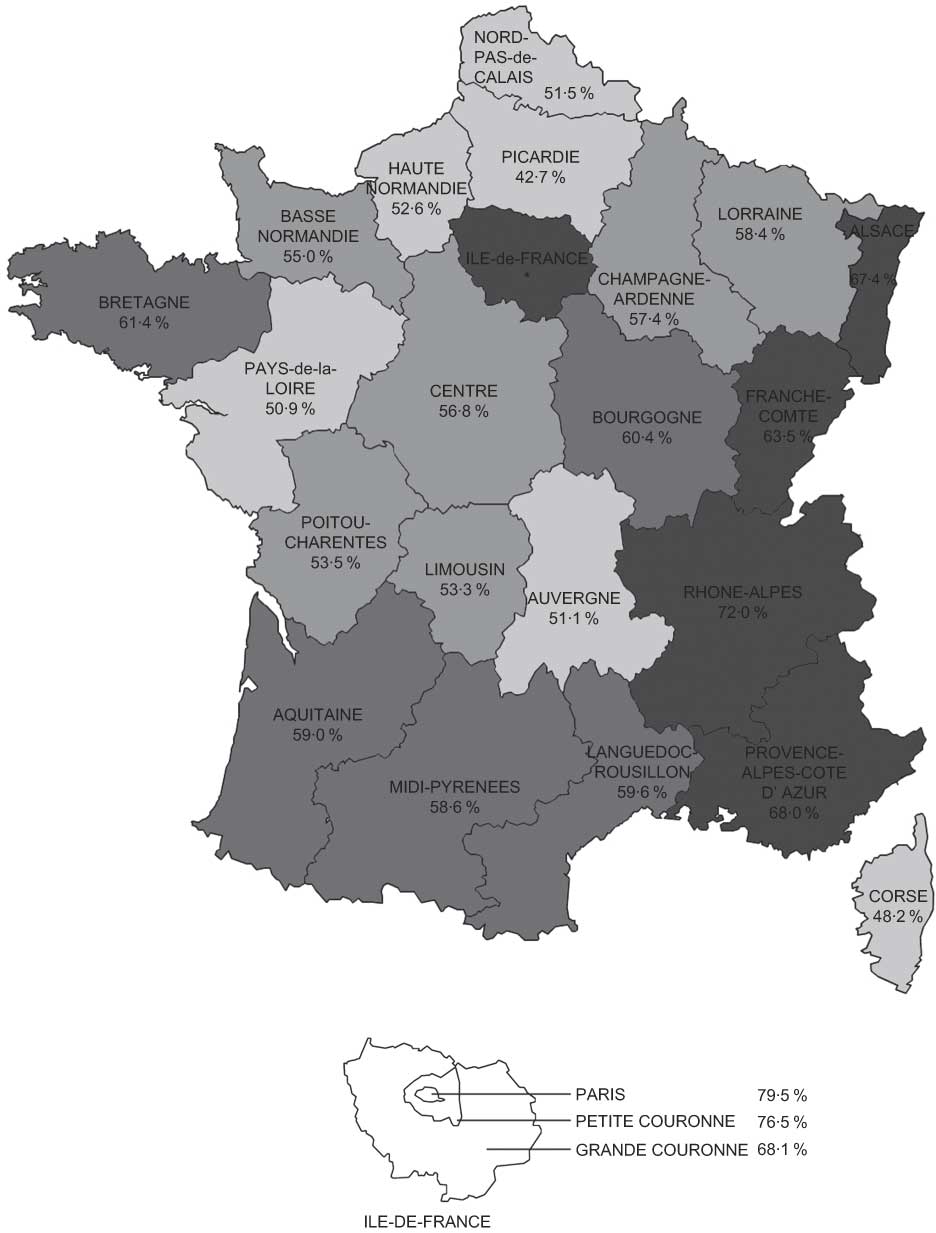

Figure 1 shows breast-feeding rates across regions in France. They were higher in Ile-de-France, Rhône-Alpes, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur and Alsace (from 67 % to 80 %) and lower in Auvergne, Pays-de-la-Loire and Picardie (from 42 % to 51 %).

Fig. 1 Breast-feeding rates in maternity units in France in 2003: ![]() , <53%;

, <53%; ![]() , 53–58%;

, 53–58%; ![]() , 58–62%;

, 58–62%; ![]() , >62%. Alsace (n 399); Aquitaine (n 571); Auvergne (n 239); Basse Normandie (n 309); Bourgogne (n 278); Bretagne (n 624); Centre (n 488); Champagne-Ardenne (n 279); Corse (n 54); Franche-Comté (n 222); Haute Normandie (n 403); Ile-de-France – Petite Couronne (n 1145), Paris (n 781), Grand Couronne (n 1094); Languedoc-Roussillon (n 478); Limousin (n 150); Lorraine (n 425); Midi-Pyrénées (n 539); Nord-Pas-de-Calais (n 995); Pays-de-la-Loire (n 802); Picardie (n 354); Poitou-Charentes (n 284); Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (n 965); Rhône-Alpes (n 1308)

, >62%. Alsace (n 399); Aquitaine (n 571); Auvergne (n 239); Basse Normandie (n 309); Bourgogne (n 278); Bretagne (n 624); Centre (n 488); Champagne-Ardenne (n 279); Corse (n 54); Franche-Comté (n 222); Haute Normandie (n 403); Ile-de-France – Petite Couronne (n 1145), Paris (n 781), Grand Couronne (n 1094); Languedoc-Roussillon (n 478); Limousin (n 150); Lorraine (n 425); Midi-Pyrénées (n 539); Nord-Pas-de-Calais (n 995); Pays-de-la-Loire (n 802); Picardie (n 354); Poitou-Charentes (n 284); Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (n 965); Rhône-Alpes (n 1308)

Breast-feeding rates also varied according to regional characteristics (Table 1). They were higher in regions with a high percentage of urban population, of residents with a university-level education and of non-French residents, and in regions with a high average salary.

Table 1 Breast-feeding rates in maternity units according to regional characteristics

*Quartiles refer to the distribution of regional variables.

†P < 0·0001 for all variables.

Variations in breast-feeding rates across regions were statistically significant (model 1), with a baseline regional variance of τ 00(1) = 0·147 (P < 0·0001; Table 2). The inclusion of individual-level variables (model 2) decreased the variance in breast-feeding rates across regions, but residual differences remained statistically significant (τ 00(2) = 0·066; P < 0·0001). The PCV was 55 % (PCV = (0·147 − 0·066/0·147) × 100 = 55 %). Hence, about half of the regional variations in breast-feeding could be explained by differences in the distributions of individual-level variables across regions. High breast-feeding rates were found mainly among women who were primiparous, non-French and from higher-status occupational groups. The measured characteristics of the infants and the maternity units in our study had little effect on breast-feeding practice and on regional variations (data available on request).

Table 2 Breast-feeding in maternity units in 2003 according to maternal and regional characteristics: results of the multi-level analysis

*Models 2–4 were adjusted for all individual-level variables in table and mode of delivery, gestational age, birth weight, multiple birth size and status of the maternity unit.

†Included regional variables in four different models (models 3a–d).

‡Included regional variables at the same time in the model.

§Regional variables were cut off at the 50th percentile; reference group ≤50th percentile.

||P < 0·0001.

¶PCV = (τ 00(1) − τ 00(2)/τ 00(1)) × 100.

Next, we introduced one regional variable at a time into four different models (model 3a–d; Table 2). After taking into account individual-level variables, including maternal education and nationality, regions with a high percentage of urban population, of people with university education or of non-French residents still had higher breast-feeding rates. The association between breast-feeding and average salary was not significant.

Residual regional variance for model 2 (which included individual-level variables only) reduced slightly with the introduction of the percentage of urban population (τ 00(3a) = 0·050). Variance for model 2 was further reduced by 50 % with the addition of a regional educational level (τ 00(3b) = 0·031) or by the percentage of non-French population (τ 00(3d) = 0·034) (i.e. PCV = (0·066 − 0·031/0·066) × 100 = 53 %). Hence, individual and regional variables (educational level or percentage of non-French population) together accounted for 79 % of the regional variations in breast-feeding (i.e. PCV = (0·147 − 0·031/0·147) × 100 = 79 %).

We used random coefficient models to examine whether the effects of certain individual-level social variables differed across regions. The results from these models did not show significant regional differences in the effects associated with maternal occupation or nationality. In addition, we did not find significant interactions between the effects of factors at the regional and individual levels: maternal occupation and regional educational level (P ≥ 0·2 for almost all occupational groups) and maternal nationality and regional non-French population (P = 0·08).

Next, we included the two regional variables most strongly associated with breast-feeding – percentage of residents with a university-level education and percentage of non-French population – in the same model (model 4). Both variables remained significantly associated with breast-feeding. Moreover, results from model 4 showed that together individual and regional variables accounted for 90 % of the regional variations in breast-feeding (i.e. PCV = (0·147 − 0·015/0·147) × 100 = 90 %).

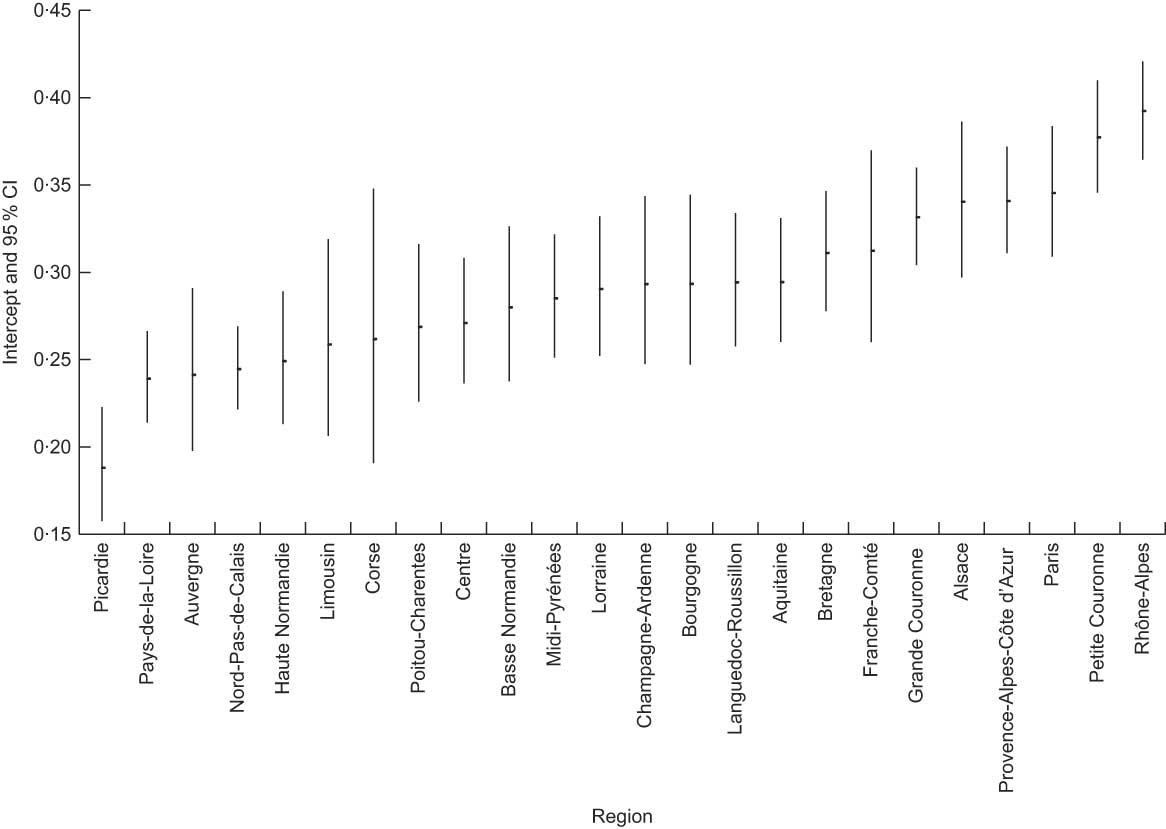

Finally, empirical Bayes residuals were used to rank regions according to their breast-feeding rates, after taking into account individual-level characteristics (Fig. 2). Formally, the empirical Bayes residuals represent regional differences in the adjusted log-odds of breast-feeding in maternity units after taking into account individual-level characteristics in different regions. Therefore, these residuals reflect indirectly adjusted regional differences in breast-feeding rates. We identified a group of regions with the lowest (Picardie, Pays-de-la-Loire, Auvergne and Nord-Pas-de-Calais) and another with the highest breast-feeding rates (Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, Paris, Petite Couronne and Rhône-Alpes). In general, CI for the empirical Bayes residuals were relatively wide. However, those for regions with the lowest breast-feeding rates did not overlap with those with the highest breast-feeding rates. In a model comparing infants only breast-fed and infants only bottle-fed, ranking of the regions for only breast-fed infants did not differ from the ranking of the regions for all breast-fed infants.

Fig. 2 Regional variations in breast-feeding in maternity units: empirical Bayes residuals; adjusted for individual-level variables (see model 2)

Discussion

Breast-feeding rates varied widely between regions and about half of the regional variations could be explained by differences in the distribution of maternal characteristics across regions. Estimates of empirical Bayes residuals in multi-level models suggested that there were regions with high breast-feeding rates and regions with low breast-feeding rates, independent of individual-level characteristics. In addition, at the regional level, a high percentage of urban population, of people with university-level education or of the non-French population had a positive effect on breast-feeding.

We chose to analyse the geographic differences in breast-feeding at the regional level for several reasons. Health policies in France are beginning to be implemented at the regional level, as stated in the French Public Health Code(24). Following recommendations in the national nutrition programme(Reference Hercberg14), since 2006, health professional networks and regional committees in charge of perinatal health are including breast-feeding promotion in their objectives. Regional breast-feeding workshops for health professionals are also organized. Analysis at the regional level is also important because regional social and demographic characteristics vary substantially across French regions(25). Finally, national statistics, such as census data, are available at the regional level.

However, our analysis at the regional level had some limitations. The small number of regions (n 24) in our sample limited the number of regional variables that could be introduced in the same model(Reference Diez-Roux26). Moreover, we were not able to assess the impact of regional breast-feeding promotion policies because data about these policies are not available systematically. Other multi-level studies have shown that policies or legislation in favour of breast-feeding explained a part of the differences between states in the USA(Reference Singh, Kogan and Dee9) or between municipalities in Brazil(Reference Venancio and Monteiro27). Nevertheless, in France, the effect of these policies in 2003 was probably slight, because programmes promoting breast-feeding were introduced only in the early 2000s.

French National Perinatal Surveys provide information about a limited number of indicators and are not designed to study specifically the questions related to breast-feeding in detail. We were therefore unable to use the complete definitions of breast-feeding using the WHO criteria(28). Furthermore, no information was collected about practices in maternity wards or breast-feeding duration. The effects of maternity unit practices within a given region are difficult to assess. However, only two out of 618 maternity units had received the Baby Friendly Hospital designation in France in 2003(Reference Cattaneo, Yngve and Koletzko29).

We identified regions with very high and very low breast-feeding rates using empirical Bayes residuals(Reference Raudenbush and Bryk23). Identification of these regions can facilitate targeting policies to promote breast-feeding, particularly in regions with very low breast-feeding rates. They may also be helpful in identifying factors or programmes that may favour breast-feeding in regions with high breast-feeding rates. The multi-level approach used in our analysis, and in particular the use of empirical Bayes residuals, is potentially applicable to a wide spectrum of evaluation studies aimed at estimating the effects associated with groups (e.g. regions, neighbourhoods, hospitals or wards). These residuals have distinct advantages because they take into account the hierarchical structure of data (group membership) and produce relatively stable estimates even when the sample sizes per group are modest(Reference Raudenbush and Bryk23).

Despite their advantages, empirical Bayes residuals have limitations as group-level indicators(Reference Raudenbush and Bryk23). There is a possible bias due to unmeasured individual-level confounders and/or model misspecifications. This is a general limitation of all multivariable regression models, including multi-level models and empirical Bayes residual estimations. Another important consideration relates to the potential problem of a statistical self-fulfilling prophecy. This can come about as the result of shrinkage of the estimates for empirical Bayes residuals towards the average value in the population for small groups (small regions). Hence, to the extent that data are unreliable for small groups, the group effects are made to conform more to expectations. Consequently, it becomes more difficult to identify small regions that represent outliers. This could be the case for Corse, the smallest region in our sample, which had the second lowest breast-feeding rate in our sample but was not identified as a low outlier region by the empirical Bayes residuals.

Our results showed a strong association between breast-feeding and maternal occupation and nationality. These associations were comparable to those identified in a previous analysis that did not take regional variations into account(Reference Bonet, Kaminski and Blondel20). In addition, using random coefficients from multi-level models, we showed that associations between breast-feeding and maternal characteristics did not differ across regions or according to the regional social context. These results suggest that maternal characteristics play an important and stable role in breast-feeding, independently of the context in which the mothers live.

The high proportion of women with maternal characteristics most favourable to breast-feeding in the regions with high breast-feeding rates(Reference Blondel, Supernant and du Mazaubrun13) explains nearly half the regional variations in breast-feeding in France. This is the case in Paris and its immediate suburbs, where many women with high-status jobs (e.g. managers, professionals or technicians) or those born in foreign countries appear to contribute to the very high breast-feeding rates in these regions compared to other French regions. In the USA, 25–30 % of the variation in maternal breast-feeding between states also appears to be explained by maternal characteristics(Reference Singh, Kogan and Dee9).

We observed that at the regional level both a highly educated population and a substantial foreign population have a positive influence on breast-feeding. Our results are consistent with those of a recent study in the USA(Reference Forste and Hoffmann30) which showed that women living in an area that is a high-risk environment for newborns (based on the indicators of the Right Start for America’s Newborns programme) were less likely to breast-feed. On the other hand, we found no relationship between breast-feeding and mean income. In some studies that used only individual-level data, breast-feeding was found to increase with maternal education(Reference Li, Darling and Maurice10, Reference Ahluwalia, Morrow and Hsia17) or poverty level(Reference Li, Darling and Maurice10, Reference Dubois and Girard18). However, when the effects of education and poverty level were assessed simultaneously, breast-feeding remained associated with maternal education but not with poverty level(Reference Dubois and Girard18).

Our results at the regional level suggest that education and culture play a more important role than standard of living. The influence of the social and cultural background on breast-feeding may be related to public knowledge of breast-feeding benefits, beliefs and attitudes, and breast-feeding practices in the general population(Reference Yngve and Sjostrom15, Reference Griffiths, Tate and Dezateux19, Reference Li, Ogden and Ballew21, Reference Li, Hsia and Fridinger22, Reference McIntyre, Hiller and Turnbull31, Reference Humphreys, Thompson and Miner32). For example, populations of foreign origin are very favourable to breast-feeding for cultural reasons(Reference Griffiths, Tate and Dezateux19). Similarly, more highly educated people are more receptive to health messages and might be more supportive of health-related behaviour, including breast-feeding(Reference Li, Ogden and Ballew21, Reference Li, Hsia and Fridinger22, Reference McIntyre, Hiller and Turnbull31, Reference Humphreys, Thompson and Miner32).

In this way, a high proportion of foreign residents may produce, through different mechanisms, an environment that is culturally supportive of breast-feeding, independent of the mother’s nationality. Regions with a high proportion of foreigners today have long been regions with high immigration rates. The role of foreign cultures may remain strong in these regions, including for mothers born in France. That is, the preference for breast-feeding seems to continue from immigrant mothers to first- and second-generation mothers(Reference Hawkins, Lamb and Cole33). In regions with a high foreign population, there may be many French women of the first or second generation – in families, among health-care professionals and in childbirth preparation or breast-feeding support groups – very favourable to breast-feeding. For example, in areas with high immigrant rates, the partners of native-born French women may more often be either foreign or from an immigrant family, and they may encourage their partners to breast-feed more frequently(Reference Griffiths, Tate and Dezateux19).

The socio-cultural context may also have an important impact on health professional practices in maternity units(Reference Hofvander34) and explain regional disparities. It has been shown that health professionals’ knowledge, experiences and beliefs influence attitudes and behaviours on breast-feeding support and promotion(Reference Furber and Thomson35, Reference Patton, Beaman and Csar36). However, we do not know how health professionals’ support in maternity units varied between regions at the time of the survey. In any case, maternity units are part of and are influenced by the general socio-cultural context, which is an important determinant of breast-feeding promotion policies. For example, breast-feeding promotion practices could be more easily adopted in maternity units within regions with a highly educated population.

Regional variations in breast-feeding may also stem from the breast-feeding practices of the preceding generation. The regional differences in 2003 are very similar to those observed in 1972(Reference Rumeau-Rouquette, Crost and Breart12), with higher breast-feeding rates in the east and Ile-de-France (Paris and its suburbs) than in the west. The literature shows that women who were themselves breast-fed, breast-feed more often(Reference Yngve and Sjostrom15). Grandmothers transmit not only their own feeding practices and beliefs, but also their confidence that breast-feeding is the normal way to feed an infant if they had breast-fed their own children(Reference Grassley and Eschiti37). Women who give birth in regions where there was a high breast-feeding rate in the past may therefore have received greater support for breast-feeding from their parents, family and friends.

Conclusion

Our study shows that a multi-level analysis including estimations of empirical Bayes residuals can identify regions with particularly high or low breast-feeding rates. This can, in turn, be helpful in targeting regional policies to promote breast-feeding, especially in regions with low breast-feeding rates. Our results suggest that strategies to be developed must also include, in all the regions, differentiated activities adapted to particular social groups to improve the attitude of the general population towards breast-feeding, to help mothers in their feeding choices for their newborns and to support health professionals in and outside maternity units in implementing breast-feeding promotion activities. Breast-feeding promotion policies at these different levels might contribute both to decreasing individual and regional differences and to increasing national breast-feeding rates.

Acknowledgements

The French National Perinatal Surveys are funded by the General Health Directorate (DGS). They are conducted by the Directorate of Research, Studies, Evaluation and Statistics (DRESS, Ministry of Health), INSERM U953 and the Mother and Child Protection Services in each district. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. M.B. was supported by a research grant from the French Ministry for Higher Education and Research. She conducted the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. B.B. coordinated the survey, proposed and designed the study, made suggestions about the analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. B.K. proposed the statistical method, supervised the statistical analyses and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript for submission. The authors thank the heads of the maternity units, the investigators and all the women who participated in the surveys.