Article contents

The application of quick response (QR) codes in archaeology: a case study at Telperion Shelter, South Africa

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 September 2016

Extract

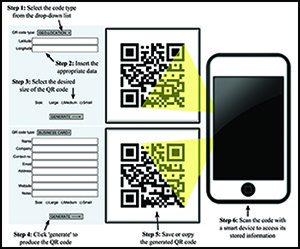

Accurate, efficient and clear recording is a key aim of archaeological field studies, but one not always achieved. Errors occur and information is not always properly recorded. Left unresolved, these errors create confusion, delay analysis and result in the loss of data, thereby causing misinterpretation of the past. To mitigate these outcomes, quick response (QR) codes were used to record the rock art of Telperion Shelter in Mpumalanga Province, eastern South Africa. The QR codes were used to store important contextual information. This increased the rate of field recording, reduced the amount of field errors, provided a cost effective alternative to conventional field records and enhanced data presentation. Such a tool is useful to archaeologists working in the field, and for those presenting heritage-based information to a specialist, student or amateur audience in a variety of formats, including scientific publications. We demonstrate the tool's potential by presenting an overview and critique of our use of QR codes at Telperion Shelter.

- Type

- Method

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Antiquity Publications Ltd, 2016

References

- 3

- Cited by