Book contents

- Linguistic Interaction in Roman Comedy

- Linguistic Interaction in Roman Comedy

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Note on texts and translations

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Part I How to command and request in early Latin

- Part II How to say “please” in early Latin, and more

- Part III How to greet and gain attention, and when to interrupt

- Part IV The language of friendship, the language of domination

- Part V Role shifts, speech shifts

- Book part

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index rerum

- Index vocabulorum et locutionum

- Index locorum potiorum

- References

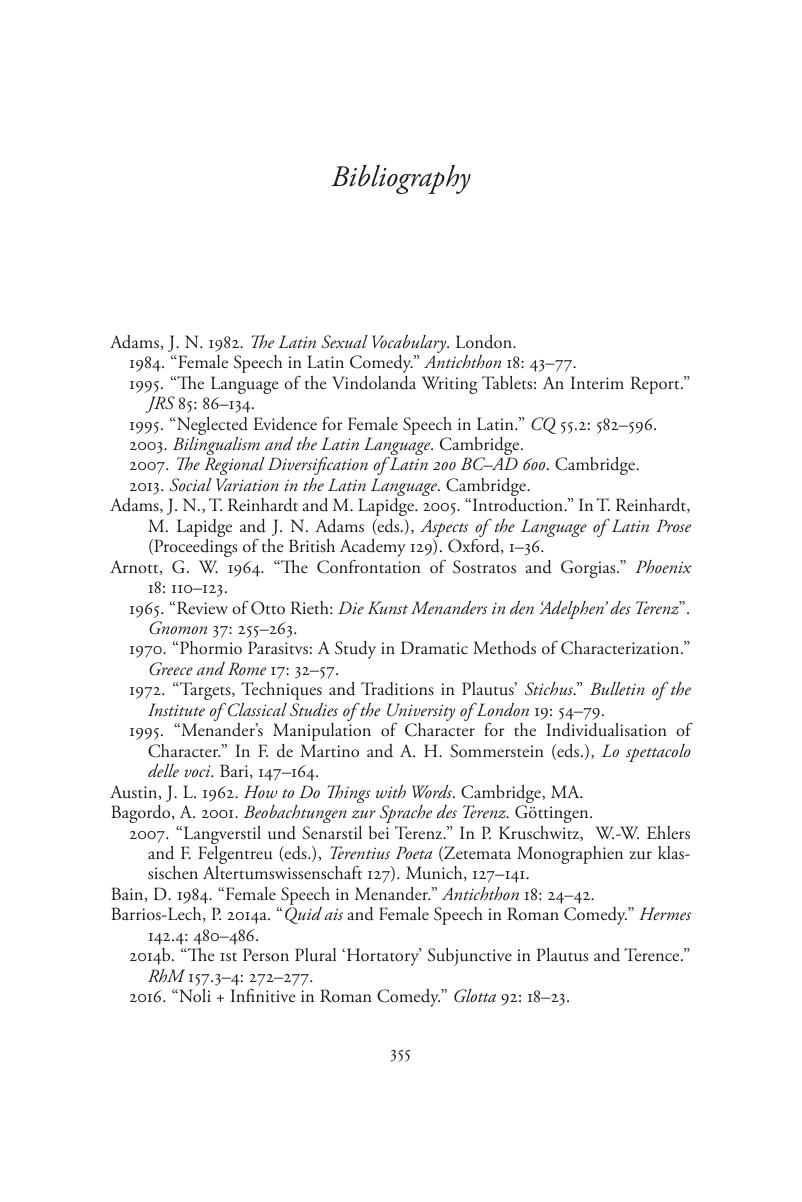

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 May 2016

- Linguistic Interaction in Roman Comedy

- Linguistic Interaction in Roman Comedy

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Note on texts and translations

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Part I How to command and request in early Latin

- Part II How to say “please” in early Latin, and more

- Part III How to greet and gain attention, and when to interrupt

- Part IV The language of friendship, the language of domination

- Part V Role shifts, speech shifts

- Book part

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index rerum

- Index vocabulorum et locutionum

- Index locorum potiorum

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Linguistic Interaction in Roman Comedy , pp. 355 - 368Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016