28 results

Characterisation of age and polarity at onset in bipolar disorder

-

- Journal:

- The British Journal of Psychiatry / Volume 219 / Issue 6 / December 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 August 2021, pp. 659-669

- Print publication:

- December 2021

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

‘Because it's easier to kill that way’: Dehumanizing epithets, militarized subjectivity, and American necropolitics

-

- Journal:

- Language in Society / Volume 50 / Issue 4 / September 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 August 2021, pp. 583-603

- Print publication:

- September 2021

-

- Article

- Export citation

9 - Part III Introduction: Collusion: On Playing Along with the President

- from Part III - The Interactive Making of the Trumpian World

-

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp 151-157

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

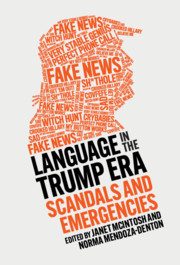

Language in the Trump Era

- Scandals and Emergencies

-

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020

Introduction: The Trump Era as a Linguistic Emergency

-

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp 1-44

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tables

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp xi-xi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Note on Transcription Conventions

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp xviii-xviii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - The Interactive Making of the Trumpian World

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp 149-214

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contributors

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp xii-xv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp x-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - Part IV Introduction: Language and Trump’s White Nationalist Strongman Politics

- from Part IV - Language, White Nationalism, and International Responses to Trump

-

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp 217-225

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - Performance and Falsehood

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp 89-148

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp 291-302

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part IV - Language, White Nationalism, and International Responses to Trump

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp 215-290

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Crybabies and Snowflakes

- from Part I - Dividing the American Public

-

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp 74-88

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp vii-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp xvi-xvii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part I - Dividing the American Public

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp 45-88

-

- Chapter

- Export citation