Introduction

In August 2012, Marcus Anthony Hunter, an urban studies scholar at the University of California, Los Angeles, was the first to post the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter on Twitter (National Public Radio 2019). The hashtag began to go viral on the social media platform after Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometti posted it on July 13, 2013 to protest a jury’s decision to acquit George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed African American teenager, during a confrontation in Sanford, Florida. In the years since this viral post, #BlackLivesMatter has been tweeted more than 35 million times—making it one of the three most used hashtags on the Twitter platform (Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark Reference Freelon, McIlwain and Clark2016; Garza Reference Garza2014; Hockin and Brunson Reference Hockin and Brunson2018). The phrase Black Lives Matter (BLM) has also acquired an off-line life as the animating principle and mantra of the movement against police brutality in Black communities in the United States (Bonilla and Rosa Reference Bonilla and Rosa2015; Jackson and Welles Reference Jackson2016; Rickford Reference Rickford2016; Taylor Reference Taylor2016, 13–15). Hundreds of large, disruptive Black Lives Matter protests have been staged in American cities since 2014. Public opinion and media studies have reported that these protests have registered in the national consciousness (Horowitz and Livingston Reference Horowitz and Livingston2016; Neal Reference Neal2017; Tillery Reference Tillery2017).

As is often the case when new movements emerge (Gusfield Reference Gusfield, Johnston, Larana and Gusfield1994, 59; Zald Reference Zald, Morris and Mueller1992), the Black Lives Matter movement has also become the subject of scholarly inquiry about how its origins, tactics, and effects fit into existing theoretical paradigms and how it is understood by others (Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark Reference Freelon, McIlwain and Clark2016; Harris Reference Harris2015; Lebron Reference Lebron2017; Merseth Reference Merseth2018; Rickford Reference Rickford2016; Taylor Reference Taylor2016; Tillery Reference Tillery2019b). The consensus within this burgeoning literature is that the Black Lives Matter movement is akin to the New Social Movements—like Germany’s antinuclear movement or the Occupy Wall Street movement in the United States—that have emerged in advanced industrialized societies since the 1980s (Harris Reference Harris2015, 35–36; Rickford Reference Rickford2016, 35–36; Taylor Reference Taylor2016, 145–148, 156–159; Tillery Reference Tillery2019b). Under this formulation, we can expect the activists associated with the Black Lives Matter movement to evince less concern with mobilizing resources to affect public policy debates or shift the trajectory of political institutions than did their predecessors in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s (Johnston, Larana, and Gusfield Reference Gusfield, Johnston, Larana and Gusfield1994; Melucci Reference Melucci1989; Pichardo Reference Pichardo1997). We can also expect Black Lives Matter activists to replace resource mobilization in the service of instrumental demands with a “politics of signification” that seeks to create a space for and represent their distinctive identities within postindustrial cultures (Johnston, Larana, and Gusfield Reference Gusfield, Johnston, Larana and Gusfield1994; Melucci Reference Melucci1989). In other words, we should observe Black Lives Matter activists devoting considerable attention to messaging about the various identity groups that they purport to represent in the public sphere.

Scholars of social movements have long acknowledged the importance of “social movement frames” both to generate support for and to mobilize individuals to participate in social movements (Goffman Reference Goffman1974; Snow and Benford Reference Benford and Snow2000; Snow et al. Reference Snow, Burke Rochford, Worden and Benford1986; Tarrow Reference Tarrow, Morris and Mueller1992). Indeed, many scholars argue that the difference between successful and unsuccessful movements hinges on the ability of their core activists to behave as “signifying agents actively engaged in the production and maintenance of meaning for constituents, antagonists, and bystanders or observers” (Snow and Benford Reference Benford and Snow2000, 613). The focus on frames within social movement studies has corresponded with the rise of the New Social Movements. Despite this fact, there has not been much empirical work on how the identity frames deployed by the leaders of New Social Movements shape public opinion and affect micromobilization. Instead, social movement scholars have tended to simply catalog the rise of new frames and describe how well they seem to “resonate” with collectivities during protests (Benford and Snow Reference Benford and Snow2000; Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck, Sikkink, Meyer and Tarrow1998, 223–226; Snow and Benford Reference Snow, Benford, Morris and Mueller1992; Snow and Machalek Reference Snow and Machalek1984). In most social movements, the framing of the movement is competitive (Carroll and Ratner Reference Carroll and Ratner1996; Benford and Snow Reference Benford and Snow2000; Zald Reference Zald, McAdam, McCarthy and Zald1996)—that is, activists from different branches of a movement tend to compete with one another to elevate their message to the position of “master frame” or dominant narrative of what the movement is about (Mooney and Hunt Reference Mooney and Hunt1996; Snow and Benford Reference Snow, Benford, Morris and Mueller1992, Bonilla and Mo Reference Bonilla and Hyunjung Mo2019). Such competition has largely been absent from the history of the Black Lives Matter movement. On the contrary, the most visible Black Lives Matter activists quickly coalesced around the view that intersectionality is the “master frame” of the movement (Chatelain and Asoka Reference Chatelain and Asoka2015; Garza, Tometti, and Cullors Reference Garza2014).

The concept of intersectionality grows out of the rich intellectual tradition of Black feminist thought in the United States (Collins Reference Collins1990; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Lorde Reference Lorde1984). The central idea animating intersectionality theory is that marginalized individuals exist and experience their racial, gender, sexual, and class identities concurrently (Hancock Reference Hancock2007; Jordan-Zachary Reference Jordan-Zachery2007; Nash Reference Nash2008). This means that interconnected forms of disadvantage exist for those who identify as part of marginalized groups across multiple identities, and this form of discrimination is unique to those with overlapping or intersectional identities, as first defined, described, and documented among African American women (Crenshaw 1989; Hancock Reference Hancock2007). The corollary of this idea is that marginalized individuals must “confront” what Collins (Reference Collins1990) calls “interlocking systems of oppression,” based on their class, gender, race, and sexual identities (3). Several recent studies in political science have demonstrated that recognition of their intersectionality is a prime motivator of African American women’s behavior in politics (Brown Reference Brown2014; Brown and Gershon Reference Brown and Gershon2016; Simien and Clawson Reference Simien and Clawson2004; Smooth Reference Smooth2006).

Our goal in this paper is to understand how the messages emanating from the leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement about their gender, sexuality, and racial identities work as social movement frames shaping both the attitudes that rank-and-file African Americans hold about the movement and their willingness to participate in it. We ask whether a framing strategy grounded in intersectionality theory works to mobilize African Americans to support and participate in the Black Lives Matter movement. Does framing the Black Lives Matter movement as addressing the “interlocking systems of oppression” lead to the same or greater levels of support for the Black Lives Matter movement and mobilization among African Americans as when the movement is framed more broadly as a fight for racial justice? Or, do movement frames predicated on marginalized subgroup identities function as micromobilizers for those bearing overlapping identities? We answer these questions through a survey experiment designed to test whether the subgroup frames are as potent as a frame based on racial identity for encouraging African Americans to adopt positive attitudes about the Black Lives Matter movement and engage in political actions to support the movement.

We believe that exploring these questions through experimental methods is warranted for three reasons. First, while there is a wealth of excellent qualitative research on the dynamics of the Black Lives Matter movement (see, for example, Chatelain and Asoka Reference Chatelain and Asoka2015; Harris Reference Harris2015; Rickford Reference Rickford2016; Taylor Reference Taylor2016), there is a dearth of causal research on the movement’s impact on African American communities. Second, because Black Lives Matter is the first avowedly intersectional movement to gain significant traction in the American public sphere, developing theoretical insights about how it shapes political attitudes and behavior holds great potential to build theory about the larger category of New Social Movements. Finally, the notion that movement frames referencing subgroup identities can be potent micromobilizers of support and action cuts against a lot of accumulated wisdom in multiple fields of study.

The remainder of the paper is organized into four sections. In the next section, we provide the theoretical context for our experimental study. We also use this section to present our main hypotheses and expectations based on extant theories. Then, in the “Methods and Data” section, we describe the design of our experiment and data collection. In the “Findings” section, we then report the results of our experiment. The main finding presented in this section is that, as compared with messages that focus on group unity, movement frames predicated on subgroup identities can demobilize support for Black Lives Matter in segments of the African American population. The conclusion describes the broader significance of the findings for our larger understanding of the Black Lives Matter movement as well as the broader literature on social movements.

Theoretical Context and Hypotheses

This paper falls within the research paradigm on social movements known as the “framing perspective” (Benford and Snow Reference Benford and Snow2000; Johnston and Noakes Reference Johnston and Noakes2005). This paradigm emerged as a corrective to the limitations inherent in the structuralism that defines the dominant resource mobilization and political process theories of social movements (Benford and Snow Reference Benford and Snow2000; Snow et al. Reference Snow, Burke Rochford, Worden and Benford1986, 464). According to resource mobilization and political process theorists, the ability to take advantage of shifts in the political opportunity structure by mobilizing resources—for example, labor, money, facilities, etc.—and sending strategic signals to dominant elites is the dividing line between successful and unsuccessful movements (Cress and Snow Reference Cress and Snow1996; Gamson Reference Gamson1975; McAdam Reference McAdam1982; Morris Reference Morris1981). Goffman (Reference Goffman1974) initiated the framing paradigm by pointing to the important role that ideational factors play in the micromobilization of a movement’s adherents.

Goffman (Reference Goffman1974, 21) defines “frames” as “schemata of interpretation that enable individuals to locate, perceive, identify, and label” events in their lives and the broader world. In Goffman’s view, the most robust social movements occur when there is “alignment” between the interpretive schemata promoted by the leaders of social movements and individual participants. Building on Goffman’s approach, Snow et al. (Reference Snow, Burke Rochford, Worden and Benford1986, 464) argue that “frame alignment is a necessary condition for movement participation, whatever its nature or intensity.” Since the mid-1980s, scholars have devoted considerable attention to the frames that social movement organizations generate to move public opinion (Bonilla and Mo Reference Bonilla and Mo2018; Lau and Schlesinger Reference Lau and Schlesinger2005) and spur their adherents to take actions in the public sphere (Gamson Reference Gamson1992; Klandermans Reference Klandermans1984; Snow and Benford Reference Snow and Benford1988).

These studies point to the importance of what Benford and Snow (Reference Benford and Snow2000) call “meaning work” to social movements. “Meaning work” is “the struggle over the production of mobilizing and countermobilizing ideas and meanings” (613). Under this view, the most important task of activists is to serve as “signifying agents” in the “production and maintenance of meaning for constituents, antagonists, and bystanders or observers” (613). Snow and Benford (Reference Snow, Benford, Morris and Mueller1992) argue that social movement organizations that successfully accomplish these core framing tasks at the beginning of a “protest cycle” are more likely to give rise to dominant or what social movement scholars call “master frames” that “resonate” with the adherents of the movement. Benford and Snow (Reference Benford and Snow2000) define “the concept of resonance” as “the effectiveness or mobilizing potency of proffered framings” (619). Snow and Benford (Reference Snow, Benford, Morris and Mueller1992) further argue that resonance is a function of “empirical credibility, experiential commensurability, and ideational centrality” (140). In other words, the potency of frames is a function of how well they match up with the lived experiences of the movement’s adherents.

The most visible activists associated with the Black Lives Matter movement have embraced the concept of intersectionality as a core tenet of their activism. This commitment translates into a framing strategy that views centering the identities of marginalized subgroups—that is, gender and LGBTQ+ identities—within the African American community as the best way to reach and mobilize their adherents (Carruthers Reference Carruthers2018; Garza Reference Garza2014; Khan-Cullors Reference Khan-Cullors and Bandele2018; Tometti Reference Tometi2015). Garza (Reference Garza2014) gives voice to this commitment in her pamphlet “A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement.” She writes:

Black Lives Matter is a unique contribution that goes beyond extrajudicial killings of Black people by police and vigilantes. It goes beyond the narrow nationalism that can be prevalent within some Black communities, which merely call[s] on Black people to love Black, live Black, and buy Black, keeping straight cis-Black men in the front of the movement while our sisters, queer and trans and disabled folk, take up roles in the background or not at all. Black Lives Matter affirms the lives of Black queer and trans folks, disabled folks, Black undocumented folks, folks with records, women, and all Black lives along the gender spectrum. It centers those that have been marginalized within Black liberation movements

(25).Garza goes on to say that this intersectional framing strategy is a necessary “tactic to (re)build the Black liberation movement” (25). In other words, for Garza, the Black Lives Matter movement’s robustness as a movement for racial justice depends on the elevation of messages about marginalized subgroups within African American communities.

Empirical research on the Black Lives Matter movement confirms that the type of signification that Garza calls for in her pamphlet is widespread among Black Lives Matter activists. Tillery’s (Reference Tillery2019b) content analysis of more than 18,000 tweets by six organizations affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement found that gender, LGBTQ+, and racial identities were among the main categories proffered by activists as master frames for the movement. Jackson’s (Reference Jackson2016) qualitative research on BLM activists also confirmed their commitment to intersectional messaging. “Black Lives Matter’s organizational founders, and members of the larger Movement for Black Lives collective,” Jackson writes, “have insisted on discourses of intersectionality that value and center all Black lives, including, among others, Black women, femmes, and queer and trans folk” (375). Despite these stated commitments from BLM activists, Threadcraft (Reference Threadcraft2017) has noted that Black female and LGBTQ+ victims have received less attention in the movement’s condemnations of state violence and rituals of public mourning.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, the progenitor of the term intersectionality, has recognized the “dilemma” that sometimes ensues when social movements have to choose between centering subgroup identities and pointing to unifying messages to mobilize the larger African American community (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989, 148). These dilemmas have been recognized by others who have investigated intersectional social movements (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2019; Einwohner et al. Reference Einwohner, Kelly-Thompson, Sinclair-Chapman, Fernando Tormos-Aponte, Wright and Wu2019; Gershon et al. Reference Gershon, Montoya, Bejarano and Brown2019). The potential conflicts between subgroups that Crenshaw worried about are precisely the reason that most social movement scholars assert that promoting what Gamson (Reference Gamson1992) calls a “collective identity” through master frames that downplay the internal diversity is the best way to mobilize adherents (Armstrong Reference Armstrong2002; Hirsh Reference Hirsch1990; Lichterman Reference Lichterman1999; Polletta Reference Polletta1998; Ward Reference Ward, Reger, Myers and Einwohner2008). This viewpoint is bolstered by experimental research conducted by social identity and self-categorization theorists in the field of psychology (Huddy Reference Huddy2001; Tajfel Reference Tajfel1978; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, William and Worchel1979; Turner et al. Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987). These related theories, which have been well tested and replicated in dozens of settings, point us to the reality that “individuals are more likely to see themselves as members of social groups under conditions in which the use of a group label maximizes the similarities between oneself and other group members, and heightens one’s differences with outsiders” (Huddy Reference Huddy2001, 134).

For understanding how intersectional identities may alter support and mobilization, we turn to social identity theory, which purports that individuals see themselves as belonging to various groups—members of sporting teams, neighborhoods, professional guilds, etc. (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1978; Turner Reference Turner, Ellemers, Spears and Dossje1999; Turner and Tajfel Reference Tajfel, Turner, William and Worchel1979). Once individuals see themselves as part of a group, they engage in a process of evaluating the groups that they are a part of—“in-groups”—and “out-groups” that they do not see themselves as holding memberships in (Hinkle and Brown Reference Hinkle, Brown, Abrams and Hogg1990; Hogg and Abrams Reference Hogg and Abrams1988; Oakes Reference Oakes, Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, William and Worchel1979). These evaluations then form the basis for judgements about the relative social values of these in-groups and out-groups (Hogg and Abrams Reference Hogg, Abrams, Abrams and Hogg1990). Thus, an individual’s “social identity” is the end result of this three-step process of self-categorization, group evaluation, and the valuation of one’s group memberships vis-à-vis out-groups (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, William and Worchel1979; Turner Reference Turner, Ellemers, Spears and Dossje1999; Turner et al. Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987). Our work is based on this idea of social identity as the main lens through which individuals engage with social movement frames. Further, we argue that, when social movement leaders attempt to propagate master frames to stimulate support and action for their movements, individuals use the three-step process of self-categorization, group evaluation, and the valuations of in-groups and out-groups to determine whether the frame appeals to them. These determinations inform whether or not the movement represents an individual’s group and how one values thier membership within that group.

We assert that these questions are even more pronounced when the leaders of social movements attempt to build master frames predicated upon multiple social identities in the ways that the core activists in the Black Lives Matter movement have attempted to do over the past several years. This is so because we know that self-categorization, the first step in the process of personal identity formation, “is an active, interpretative, judgmental process, reflecting a complex and creative interaction between motives, expectations, knowledge and reality” (Turner Reference Turner, Ellemers, Spears and Dossje1999, 31). As a result, the social category that an individual feels she belongs to can shift quite rapidly in response to a variety of stimuli (Oakes Reference Oakes, Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987; Turner Reference Turner, Ellemers, Spears and Dossje1999). The literature is also clear that the stimuli that seem to matter most in generating these shifts for individuals in a given “social context” are the ones that are “salient”—meaning held at “the top of their mind” (Oakes Reference Oakes, Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987). Moreover, building on the same concept of salience, public opinion scholars have also demonstrated that frames generated by elites to engage potential adherents must be both cognitively accessible (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Iyengar Reference Iyengar1990) and perceived as applicable to their lives (Eagly and Chaiken Reference Eagly Alice and Chaiken1993; Higgins Reference Higgins, Higgins and Kruglanski1996) in order for individuals to embrace them and modify their attitudes and behavior.

Both the traditional strategies of social movement leaders and an understanding of social identity theory indicate that Black Lives Matter should gain traction from the Black community as a whole by using unifying messages. For decades, public opinion studies have shown that African Americans have a strong racial group consciousness (Chong and Rogers Reference Chong and Rogers2005; Dawson Reference Dawson1995; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981; Shingles Reference Shingles1981). Many studies have also found that racial group consciousness is an important force motivating African Americans to participate in politics at higher levels than those predicted by their relatively low levels of educational attainment and income (Harris-Lacewell Reference Harris-Lacewell2003; Hoston Reference Hoston2009; Olsen Reference Olsen1970; Orum Reference Orum1966; Verba and Nie Reference Verba and Nie1972; White et al. Reference White, Philpot, Wylie and McGowen2007). Dawson (Reference Dawson1995) found that African Americans also place group considerations at the center of their decision making as they form attitudes and preferences about policies and political candidates. Thus, there is ample reason to believe that collective racial identity will matter for the modal subject in our sample, justifying our first hypothesis:

H1: Black nationalist frames of the BLM movement will increase support of the movement among African American subjects.

Black Lives Matter activists have often cast their commitment to intersectional frames as diametrically opposed to what Garza (Reference Garza2014) calls “the narrow nationalism that can be prevalent in some Black communities” (25). The Black Lives Matter activists’ viewpoint cuts against the findings of public opinion studies that have shown that African Americans who believe in some of the key constructs of modern Black Nationalism demonstrate a greater sense of efficacy and a higher likelihood to participate in politics (Brown and Shaw Reference Brown and Shaw2002; Dawson Reference Dawson2003). We anticipate the Black Nationalist frame of the Black Lives Matter movement to be a potent frame generating the mobilization of positive attitudes and action.

There is a further consideration: by centering gender and LGBTQ+ identities as the master frames of the Black Lives Matter movement and downplaying traditional movement frames centered on racial unity, do the core activists in the vanguard of the movement generate conditions that weaken their ability to maximize the support and mobilization of their adherents? In order to answer this question, we first consider how amplifying messages around gender identity may alter support. Again, there are a number of complex factors to consider. Several studies have shown that group consciousness grounded in gender identity was a potent mobilizer of women’s participation in both social movements and electoral politics (Cole, Zucker, and Ostrove Reference Cole, Zucker and Ostrove1998; Fendrich Reference Fendrich1974; Rinehart Reference Rinehart2013; Weldon Reference Weldon2011; White Reference White1999). In addition, a number of public opinion studies conducted at the height of the women’s movement in the United States found that African American women demonstrated a higher commitment to feminist values than did white women (Hooks Reference Hooks1981; Klein Reference Klein, Katzenstein and Mueller1987; Mansbridge and Tate Reference Mansbridge and Tate1992). More recent studies have also confirmed that feminist consciousness drives African American women to heightened levels of engagement, participation, and substantive representation in the politics of the African American community (Brown Reference Brown2014; Brown and Gershon Reference Brown and Gershon2016; Simien and Clawson Reference Simien and Clawson2004; Smooth Reference Smooth2006). Building on the findings of these studies, we believe that the gender identity frame will have significant resonance and potency as a mobilizer of African American women.

It is less clear how Black men will respond to frames of the Black Lives Matter movement that center gender identity because there is very little empirical research on the attitudes of African American men toward gender equality and feminism.Footnote 1 One of the few analyses of gender differences in attitudes toward feminism within the African American communities finds that male respondents to the 1993–1994 National Black Politics Study “are equally and, in some cases, more likely than are black women to support black feminism” (Simien Reference Simien2004, 331). In light of this finding, it is plausible that African American men will also show a positive response to the gender identity frame. However, Simien (Reference Simien2004) also found that, despite their abstract commitments to gender equality, the African American men that she studied had a difficult time accepting the premise that gender discrimination was as big a problem as racial discrimination for African American women (333). Simien extrapolates from this finding to theorize that, when asked about both the women’s movement and the movement for racial justice, “it is more difficult for black men to uphold the black feminist position because they must consider whether black women experienced sexism within the black movement” (333). Simien’s argument is bolstered by the general findings of Davis and Robinson (Reference Davis and Robinson1991) that men are less likely than women are to see gender inequalities in their workplaces and to support the policies designed to reduce them. Based on these considerations, our second hypothesis follows:

H2: Black feminist frames of the BLM movement will increase support of the movement among African American women, but they may decrease support among male subjects.

While the findings of these studies inform our prediction that the gender identity frame is likely to demobilize support and action among the African American men in our sample, we want to be clear that our theory is not grounded in an empirical analysis of gender relations in the African American community. Instead, it is based on our assumptions about how individuals weigh the salience of frames against calculations about their social identities. In short, African American men may not see the framing of Black Lives Matter around gender as salient to their core racial and gender identities. Moreover, we believe that frames that center gender while simultaneously using the phrase “Black Lives Matter” likely create what Chong and Druckman (Reference Chong and Druckman2007) call a “competitive context” that “will stimulate individuals to deliberate over alternatives in order to reconcile competing considerations” (110). The public opinion literature on framing also suggests that such deliberations tend to result in individuals choosing the frame that is the most cognitively accessible and applicable to their individual lives (Druckman Reference Druckman2004; Kuklinski et al. Reference Kuklinski, Quirk, Jerit and Rich2001) as well as the one that invokes deeply ingrained cultural values and norms (Chong Reference Dennis2000; Gamson and Modigliani Reference Gamson and Modigliani1989).

Finally, we turn to how an intersectional identity featuring LGBTQ+ identities may be received.Footnote 2 Representation of Black queer and feminist scholarship is at the forefront of Black Lives Matter and many Black activists (Carruthers Reference Carruthers2018; Khan-Cullors and Bandele Reference Khan-Cullors and Bandele2018). While the activism of Black LGBTQ+ communities is not new to the BLM movement, Lorde (Reference Lorde1984, 137) details how, through the 1960s, the “existence of Black lesbian and gay people was not even allowed to cross the public consciousness of Black America.” However, the centering of the Black queer feminist organizations, like Charlene A. Carruthers’s BYP100, is a shift in the narratives of current Black leadership (Bailey Reference Bailey2018; Cohen and Jackson Reference Jackson2016; Green Reference Green2018). And, as Black LGBTQ+ individuals continue to be much less represented in discussions of Black Lives Matter (Threadcraft 2018), we expect to find that the LGBTQ+ identity frame will be the least potent of the three frames that we test in our survey experiment. Indeed, we expect that only those African Americans who are in the LGBTQ+ community will be mobilized in response to the LGBTQ+ identity frame. For those who are not members of the LGBTQ+ community, we anticipate much less support as the result of a LGBTQ+ frame. Public opinion research has documented the wide distribution of homophobic attitudes among the American public (Brewer Reference Brewer2003; Herek Reference Herek2000; Schulte and Battle Reference Schulte and Battle2004; Sherrill and Yang Reference Sherrill and Yang2000). While acceptance of LGBTQ+ Americans has increased markedly since the 1990s (Brewer Reference Brewer2003; Wilcox and Norrander Reference Wilcox, Norrander and Wilcox2002; Wilcox and Wolpert Reference Wilcox, Wolpert, Rimmerman, Wald and Wilcox2000), a high number of Americans, in general, remains committed to the view that homosexuality is “immoral” (Herek Reference Herek2000).

Studies of African Americans’ attitudes toward their fellow citizens with LGBTQ+ identities have produced interesting and mixed results. On one hand, African Americans are significantly more likely than whites are to support government policies and interventions to prohibit discrimination against LGBTQ+ Americans (Lewis Reference Lewis2003; Pew 2014). At the same time, African Americans are less likely than are their white counterparts to express their personal approval of homosexual relationships and same-sex marriage (Lewis Reference Lewis2003; Pew 2019). In her landmark study of the HIV/AIDS crisis in Black America, Cohen (Reference Cohen1999) argues that LGBTQ+ African Americans were frequently “hyper-marginalized” within their communities because establishment leaders did not do enough to frame their issues as central to the broader racial group’s agenda. Strolovitch’s (Reference Strolovitch2006) large-N study also finds that this tendency to “downplay the issues” of “marginalized subgroup populations” was widespread among national advocacy organizations even when they had the “good intentions” to provide representations to these subgroups. Purdie-Vaughns and Eibach (Reference Purdie-Vaughns and Eibach2008) have suggested that such dynamics stem from a type of “prototypical thinking” about social identity that leads to the “intersectional invisibility” of marginalized subgroups. Building on these findings, our final hypothesis is that

H3: Black LGBTQ+ frames of the BLM movement will have a positive effect on Black LGBTQ+ members, but they will have no effect or a demobilizing effect on Black subjects who do not identify as LGBTQ+.

Methods and Data

We tested our three hypotheses using a survey experimentFootnote 3 that manipulates how the Black Lives Matter movement is framed and measures the resulting effect on an individual’s support for the movement, expressed generally, and willingness to take action in support of the movement by contacting a representative about it. We distributed the survey to an African American sample (census matched on gender, age, and region) of 849 respondents through a Qualtrics panel from February 15, 2019, through February 23, 2019.

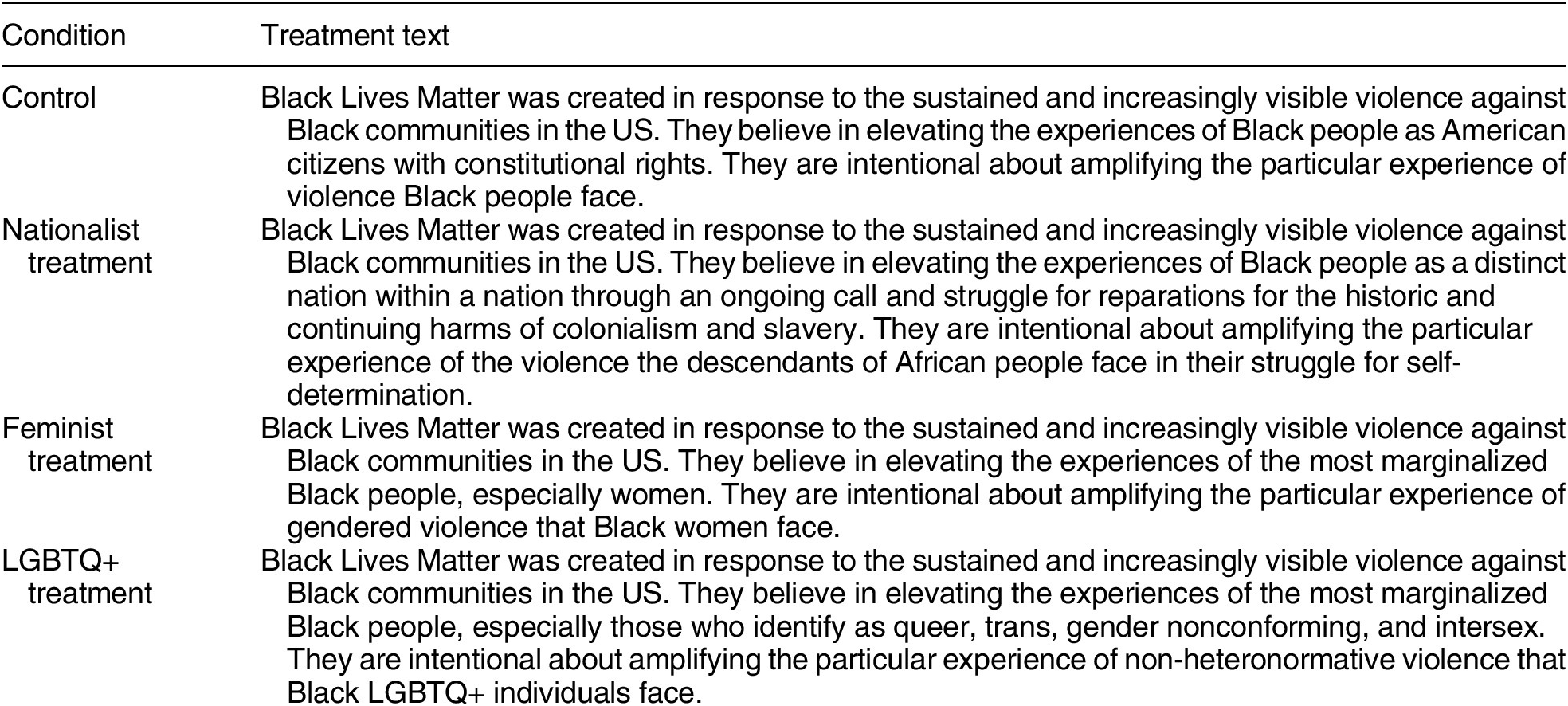

As the main objective of this experiment was to determine which identity frames change how the Black Lives Matter movement resonates with potential supporters, we presented four different treatments to subjects through short introductions to the movement. It is unrealistic to expect that most African American adults have never heard of the BLM movement, so, in addition, we used a control treatment that provided a basic description of BLM: “Black Lives Matter was created in response to the sustained and increasingly visible violence against Black communities in the US. They believe in elevating the experiences of Black people as American citizens with constitutional rights. They are intentional about amplifying the particular experience of violence Black people face.”

For our first treatment, the Black nationalist frame of the Black Lives Matter movement, we provided an even stronger, unifying statement about the Black community. The ideology of Black Nationalism has a long and complex history in African American communities (Bush Reference Bush1999; Moses Reference Mueller and Mueller1988; Robinson Reference Robinson2001; Tillery Reference Tillery2011). The earliest variants of Black nationalist thought proposed that the solution to the racial oppression and unequal citizenship in the United States was for African Americans to establish a separate nation of their own (Moses Reference Mueller and Mueller1988; Robinson Reference Robinson2001; Tillery Reference Tillery2011). Calls for the establishment of a separate nation declined in the wake of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, but several of the core constructs related to nationalist ideology continue to circulate in African American communities (Block Reference Block2011; Brown and Shaw Reference Brown and Shaw2002; Davis and Brown Reference Davis and Brown2002; Dawson Reference Dawson2003; Harris-Lacewell Reference Harris-Lacewell2004; Price Reference Price2009). To create this first treatment, we rephrased the last two sentences of the control treatment to emphasize the Black experience “as a distinct nation within a nation through an ongoing call and struggle for reparations for the historic and continuing harms of colonialism and slavery.” (See Table 1 for the full treatment texts.)

Table 1. Full Text of Experimental Conditions

The second and third treatments both signal the intersectionality of the movement in different ways. The Black feminist treatment changed the last two sentences by emphasizing the “particular experience” of “Black women” as the “most marginalized” group. The Black LGBTQ+ identity treatment placed emphasis on the particular experiences of Black LGBTQ+ individuals in the US by denoting their experiences as unique and attending to the “particular experience of non-heteronormative violence that Black LGBTQ+ individuals face.”

After randomly providing respondents with one of these treatments, which highlight different social movement frames, we asked the study subjects a series of questions about their support of the Black Lives Matter movement, in general, as well their perceptions of its effectiveness, their trust in its goals, and their assessments of the strategic decision making of the core activists guiding the movement. (Please see the full text of these questions in Appendix A.) In addition, we used a quasi-behavioral metric to measure distinctions between attitudes of support and real behavior. Following the attitudinal measures, we asked respondents whether they would be willing to write to the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), on behalf of the goals of the Black Lives Matter movement, and, if respondents agreed, we gave them space to write her a message.Footnote 4 Admittedly, writing a letter of support is not the only signal of support that individuals can send. However, we argue that this measure gives a unique opportunity for subjects to demonstrate a greater level of effort to support BLM than the attitudinal measures alone and display their perspective of what BLM stands for while performing a fundamental feature of BLM’s successes: to change dialogues about race in this country (Taylor Reference Taylor2016).

Results

We estimated the effects of the treatments on the dependent variable measures through a standard OLS regression with robust standard errors and report the coefficients and 95% confidence intervals comparing each treatment with the control condition. To more easily interpret the effect of each of the treatments, we first transformed all dependent variable measures to a 0 to 1 scale, meaning that all estimates can be read as 100 × β percentage-point differences between the control and the treatment conditions. We report respondents’ support for BLM, perceived effectiveness of BLM, and agreement with the goals of BLM. As another measure of support, we created an index including three additional variables: trust in people involved in BLM, trust in BLM leaders, and belief that BLM speaks for the individual.Footnote 5

On the whole, the sample roughly matches that of African American residents of the United States of America.Footnote 6 (Table A.1 in the Appendix contains a descriptive summary of all demographic and dependent variables. Treatments were fully balanced across various demographic groups—see Table A.2 in the Appendix.) As Figure 1 illustrates, respondents generally reported that they possess high levels of linked fate (μ = 0.77, SE = 0.29) and that identifying as Black is extremely important to most participants (μ = 0.87, SE = 0.24). In general, respondents across treatment groups were relatively familiar with Black Lives Matter (μ = 0.67, SE = 0.27) and strongly supported BLM across all dependent variable measures (μindex = 0.73, SE = 0.24). (See Figure 1 for a visual representation of these variables.)

Figure 1. Distribution of Black Identity and Main Dependent Variables

Then, we examined the effects of the three different treatments versus the control on the dependent variables for the full sample in Figure 2A.Footnote 7 For all dependent variables, the Black nationalist treatment, while mostly positive, produced no statistically significant difference from the control. In contrast, both the Black feminist and Black LGBTQ+ treatments negatively affected agreement with and support for the Black Lives Matter movement, though not significantly so. For the Index measure, the Black feminist treatment is 4.1% lower than the control (p = 0.08Footnote 8). This effect is less strong for the Black LGBTQ+ treatment, which negatively affects responses by 3.1 percentage points (p = 0.19).

Figure 2A. The Effects of Messages on Support for Black Lives Matter

Per our theory, we anticipated a differential response to the Black feminist treatment by gender.Footnote 9 When we moderated the sample based on the gender of the respondent, we found consistent results across all treatments, and we present those results in Figure 2B. For female respondents, we see nonsignificant (positive) effects of the Black nationalist (β = 0.03, p = 0.39) and Black LGBTQ+ treatments (β = 0.03, p = 0.30), and nonsignificant (negative) effects of the Black feminist treatment (β = -0.02, p = 0.46). In contrast, we found that male respondents were much more affected by the intersectional treatments. Again, the Black nationalist treatment had no significant results on evaluations of BLM (βNationalist = -0.01, p = 0.76), but both the Black feminist and Black LGBTQ+ treatments decreased Black male approval of BLM (βFeminist = -0.06., p = 0.07; βLGBTQ+ = -0.09, p = 0.008).Footnote 10

Figure 2B. The Effects of Messages on Black Lives Matter, Moderated by Respondent Gender

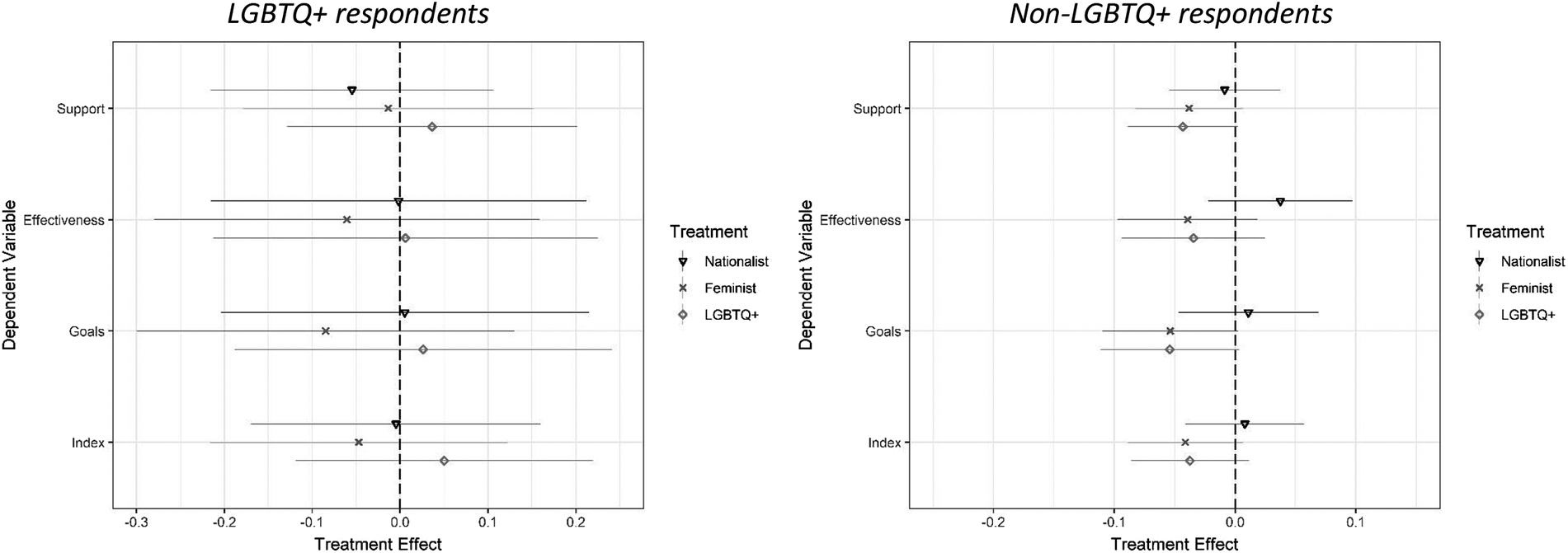

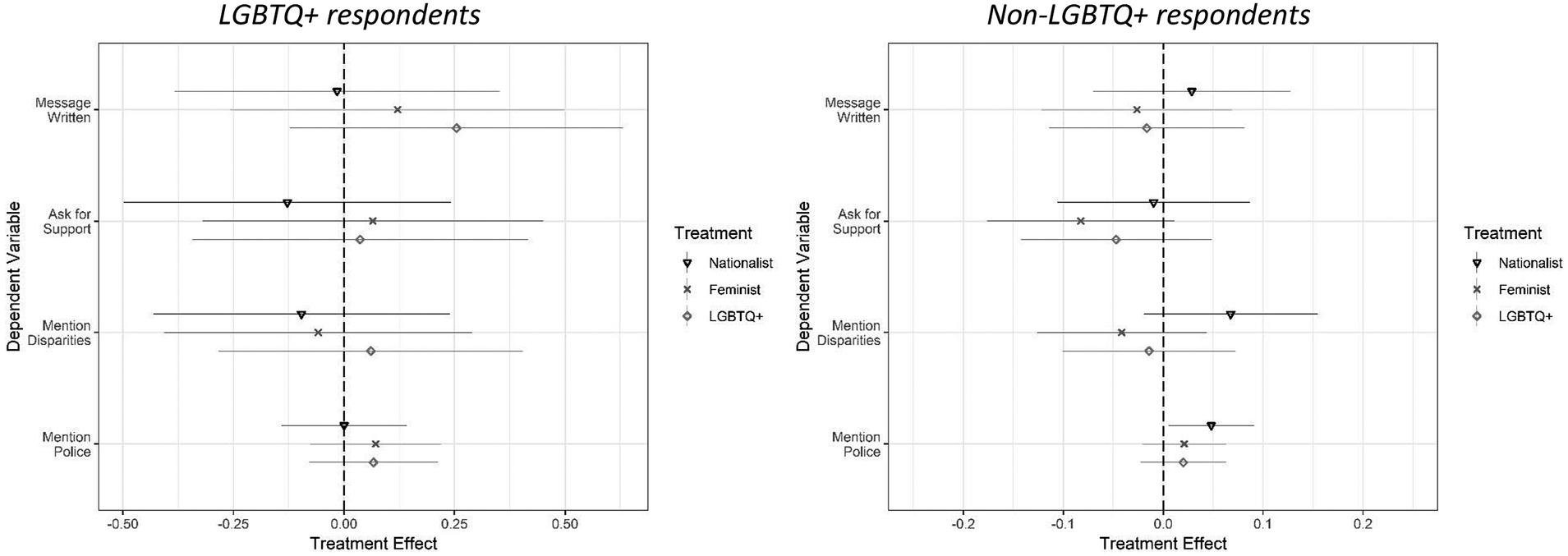

We anticipated different results for the LGBTQ+ treatment when we moderate by membership in the LGBTQ+ community.Footnote 11 Only 58 subjects identified as members of the LGBTQ+ community out of 849 respondents, approximately 6.8% of the sample.Footnote 12 As Figure 2C shows, for LGBTQ+ members, we see no message having an effect significantly different from zero. Because this sample is underpowered, it is impossible to draw any conclusions. However, among the 791 non-identifiers, we see similar negative trends for those who received the feminist message and the LGBTQ+ message(βFeminist = -0.04., p = 0.09; βLGBTQ+ = -0.04, p = 0.13), though these numbers do not quite reach traditional levels of statistical significance.

Figure 2C. The Effects of Messages on Black Lives Matter, Moderated by Respondent LGBTQ+ Identity

From our hypotheses, we anticipated that support for BLM would be differential among the intersectional treatments, though not among the unifying Nationalist treatment. Indeed, we see differential effects for the Feminist and LGBTQ+ treatments; however, instead of mobilizing women or LGBTQ+ members, we actually see a small but significant decrease in mobilization among men and those who do not identify as LGBTQ+, with strongest results among the Black males in our sample. Despite these changes, it is important to note that the support for BLM among men remains higher than the midpoint of the scale.

By using our second set of measures, the open-ended letters to Nancy Pelosi, we begin to see further differences in the precise results of the three messages. When we examine the effect that the three treatments have on political efficacy, we see further support for the general notion that mentioning specific groups in the general context of BLM depresses support of the movement. We also see a hint that, while an emphasis on BLM as a nationalist movement does not necessarily increase support, it does change how individuals respond to the movement. Of the 849 subjects, 504 (59.4%) indicated they would be willing to write a letter of support for BLM to Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. Of those, 448 (53% of the total sample) wrote a message to Pelosi, and 56 subjects responded with gibberish, an unrelated statement, or indicated that they needed more time to think about what to say.Footnote 13 We coded these subjects as noncompliant and excluded them from the substantive analysis that follows. As Figure 3 shows, on average, the subjects wrote relatively short messages with 92.38 characters (SE = 146.8). Overall, the treatments did not predict whether or not individuals actually wrote a response to Speaker Pelosi or whether individuals even said they would write a response. (See Appendix Table C.11.) However, regardless of treatment group, respondents who were more supportive of BLM and had higher levels of linked fate were more likely to write a letter to Speaker Pelosi.

Figure 3. Distribution of Respondents Who Wrote a Message to Speaker Pelosi

To further investigate whether the various treatments affected how individuals wrote, we hand-coded all messages. First, we coded dummy variables for whether respondents specifically mentioned disparities faced by Black people generally, Black men, Black women, or Black LGBTQ+ identifiers. Second, we coded whether or not respondents asked specifically for Speaker Pelosi to support the BLM movement and whether or not individuals specifically mentioned the police. Strikingly, while there were 27 mentions of Black men, there were only 2 mentions of particular struggles of African American women and no mentions of the Black LGBTQ+ community. Needless to say, the treatments did not cause differences in particular subgroup mentions in the letters.

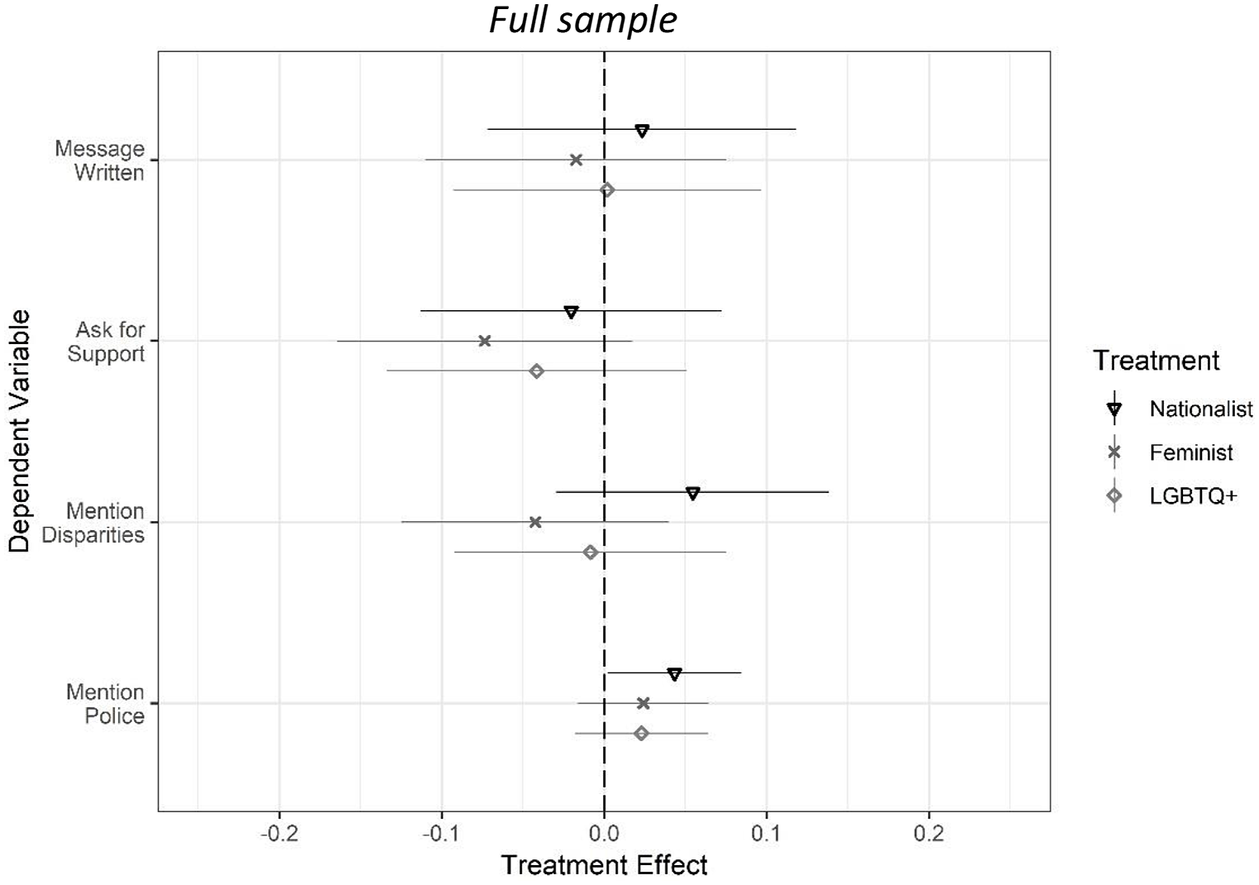

The treatments did, however, alter whether respondents asked for support, invoked police brutality, and mentioned injustices faced by Black citizens generally, as displayed in Figure 4A. Only the Black nationalist treatment positively and significantly increased mentions of the police over the control (βNationalist = 0.04, p = 0.04; βFeminist = 0.02, p = 0.24; βLGBTQ+ = 0.02, p = 0.27); similarly, the only treatment that increased mentions of disparities faced by Black individuals was the Black nationalist treatment (β = 0.05, p = 0.22), but not significantly so. And, while there was no statistically significant effect, the Black feminist treatment reduced petitions for support (β = -0.07, p = 0.11).

Figure 4A. The Effects of Messages on Letters of Support for Black Lives Matter

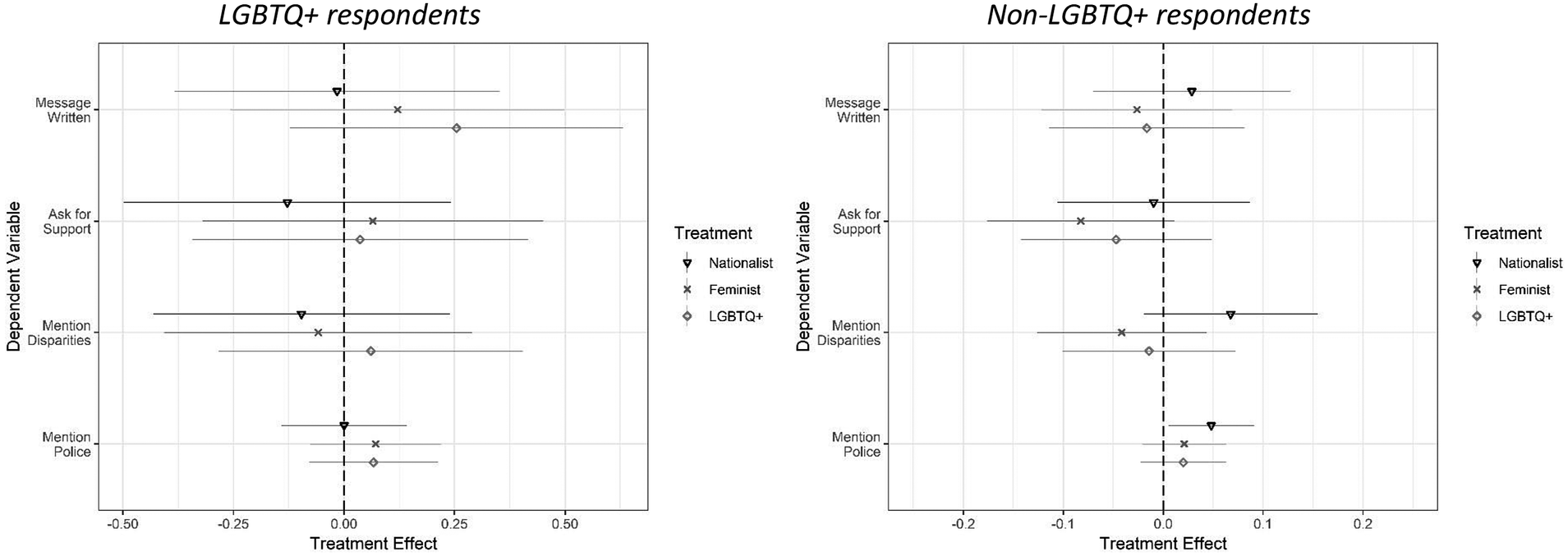

We examine how the intersectional definitions of Black Lives Matter changed subject engagement in the messages, displaying these results in Figures 4B and 4C. It is important to recognize that power decreases significantly in these analyses because just over half of our respondents wrote a message and the subgroup analyses further decrease our sample size. Nonetheless, it is important to note that several differences remain. First, men who received the Nationalist treatment were more likely to mention disparities (βNationalist = 0.10, p = 0.11). Although very little differed for men who wrote, their messages were shorter if they received the LGBTQ+ treatment (βLGBTQ+ = -37.55 characters, p = 0.07). Women who received the Nationalist treatment were more likely to mention the police (βNationalist = 0.06, p = 0.02). The LGBTQ+ condition also increased the likelihood that women would mention the police, though by a smaller amount (βLGBTQ+ = 0.04, p = 0.08).

Figure 4B. The Effects of Messages on Letters of Support for Black Lives Matter, Moderated by Respondent Gender

Figure 4C. The Effects of Messages on Letters of Support for Black Lives Matter, Moderated by Respondent LGBTQ+ Identity

Second, due to the small size of this group, we drew no conclusions from the LGBTQ+ group. The 25% positive shift in asking for support for BLM as a result of the LGBTQ+ treatment suggests that this group may be more mobilized, but since p = 0.18, we cannot confirm this conclusion here. We saw a significant decrease in the length of messages for the LGBTQ+ identifiers if they received the Nationalist or LGBQT+ treatments (βNationalist = -175.02 characters, p = 0.01; βLGBTQ+ = -134.41 characters, p = 0.17). For those not identifying as LGBTQ+, we saw a stronger negative effect in asking for support as a result of the Feminist treatment than LGBTQ+ treatment (βFeminist = -0.08, p = 0.08; βLGBTQ+ = -0.04, p = 0.34). We also saw a significant increase in mentions of the police for non-identifiers who received the Nationalist treatment (βNationalist = 0.05, p = 0.03). What is important to note here is that, while we do not necessarily see an increase for women and LGBTQ+ members in the content of their letters, we also do not see a decrease in the willingness to ask for support as a result of the intersectional treatments among men and non-LGBTQ+ members.

Discussion and Conclusion

The Black Lives Matter movement has organized hundreds of protests against police brutality and other forms of state violence against African Americans since 2014 (Bonilla and Rosa Reference Bonilla and Rosa2015; Jackson and Welles Reference Jackson2016; Rickford Reference Rickford2016; Taylor Reference Taylor2016). The most visible activists associated with the Black Lives Matter movement have placed the concept of intersectionality at the heart of their organizing efforts (Chatelain and Asoka Reference Chatelain and Asoka2015; Garza, Tometti, and Cullors Reference Garza2014), and Black Lives Matter activists practice intersectionality by consistently centering gender and LGBTQ+ identities in the social movement frames that they deploy to reach their adherents (Jackson Reference Jackson2016; Tillery Reference Tillery2019b). As we have seen, the leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement believe that this type of signification is the key to expanding support for and participation in their movement (Garza Reference Garza2014). We tested this proposition through a survey experiment that presented 849 African American subjects with four different frames of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Building on insights from research on social identity theory, we anticipated that the three identity frames would have differential effects on segments of the African American community. We expected that the Black nationalist frame would be the most potent of the three frames for mobilizing positive attitudes and stimulating actions in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. Surprisingly we found that support for Black Lives Matter movement did not increase overall as a result of the Black nationalist treatment exposure, though we did see changes in how individuals asked for support and greater specificity within their messaging.

We also predicted that the two frames predicated on marginalized subgroups, Black feminist and LGBTQ+, would splinter and sometimes depress mobilization among our test subjects, and we found support for this hypothesis. Our prediction was that these intersectional frames would increase support among subgroup members and possibly demobilize non-subgroup members, but we only found evidence that intersectional identities demobilize non-subgroup members.

We predicted that the LGBTQ+ identity frame would not be salient to most of our test subjects. Moreover, given our awareness of Cohen’s (Reference Cohen1999) research on the “hyper-marginality” and Purdie-Vaughns’s and Eisbach’s (Reference Purdie-Vaughns and Eibach2008) arguments about “intersectional invisibility,” we expected exposure to the LGBTQ+ frame to demobilize most of the subjects who were exposed to it. Our findings were consistent with this expectation. In addition, while we did see nonsignificant positive mobilization from LGBTQ+ members, we simply did not have a large enough subsample to draw conclusions about this group. Importantly, the decrease in support across both intersectional frames was particularly pronounced for the African American men in our sample.

All in all, these data largely support our hypothesis that social movement frames based on subgroup identities can generate segmented public support for those movements. This has broad implications for the study of social movements. As we have seen, the leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement adopted their intersectional messaging strategy in part because they believed that it would boost support for the movement in African American communities (Garza Reference Garza2014; Jackson Reference Jackson2016). In recent years, feminist scholars of social movements have increasingly argued that we should expect higher rates of participation and greater capacity from racial justice movements that utilize intersectional frames (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Ray, Summers and Fraistat2017; Einwohner et al. Reference Einwohner, Kelly-Thompson, Sinclair-Chapman, Fernando Tormos-Aponte, Wright and Wu2019; Ferree Reference Ferree, Lombardo and Meier2009; Lindsey Reference Lindsey2015; Terriquez Reference Terriquez2015). The findings from our survey experiment suggest that using gender or LGBTQ+ identity frames as the master frame for the Black Lives Matter movement does not mobilize any particular subgroup more, but does demobilize African American men. While further investigation is required to parse out precisely why African American men demobilize in response to these frames, this adds to growing literature about the difficulty of creating movements that are both viewed as intersectional and are widely supported (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2019; Threadcraft Reference Threadcraft2017).

Further studies should also focus on determining why African American women are mobilizing more than men in response to every frame that we exposed them to in our survey experiment. A raft of recent studies have demonstrated that, in terms of both their political behavior and their representation of their community’s interests as elected officials, African American women are now the center of gravity in African American politics (Brown Reference Brown2014; Gillespie and Brown Reference Gillespie and Brown2019; Orey et. al. Reference Orey, Smooth, Adams and Harris-Clark2006; Philpot and Walton Reference Philpot and Walton2007; Tillery Reference Tillery2019a). Yet in our study, while it is true that the gender identity frame had strength in mobilizing African American women, it was not as potent as the Black nationalist frame in boosting their activism on behalf of the Black Lives Matter movement. Jackson (Reference Jackson2019) points to key differences between political responses of African American women, suggesting that African American women are generally more responsive to threats to the African American community. Our research underlines the greater responsiveness among women, despite the movement message, and points to the importance of investigating how African American women respond in political environments where multiple movement frames compete for their attention.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000544.

Replication materials can be found on Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IUZDQI.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.