36 results

The Politics of Legal Pluralism in a Muslim Society

-

- Journal:

- Nationalities Papers , FirstView

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 May 2024, pp. 1-3

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Religion, family structure, and the perpetuation of female genital cutting in Egypt

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Demographic Economics / Volume 86 / Issue 3 / September 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 September 2020, pp. 305-328

-

- Article

- Export citation

Authoritarian media and diversionary threats: lessons from 30 years of Syrian state discourse

-

- Journal:

- Political Science Research and Methods / Volume 9 / Issue 4 / October 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 June 2020, pp. 693-708

-

- Article

- Export citation

Contesting Authoritarianism: Labor Challenges to the State in Egypt. By Dina Bishara. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. 204p. $82.99 cloth, $29.99 paper.

-

- Journal:

- Perspectives on Politics / Volume 17 / Issue 4 / December 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 November 2019, pp. 1241-1242

- Print publication:

- December 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

Muslim Trade and City Growth Before the Nineteenth Century: Comparative Urbanization in Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia

-

- Journal:

- British Journal of Political Science / Volume 51 / Issue 2 / April 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 November 2019, pp. 845-868

- Print publication:

- April 2021

-

- Article

- Export citation

Political cultures: measuring values heterogeneity

-

- Journal:

- Political Science Research and Methods / Volume 8 / Issue 3 / July 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 October 2019, pp. 571-579

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Impact of Holy Land Crusades on State Formation: War Mobilization, Trade Integration, and Political Development in Medieval Europe

-

- Journal:

- International Organization / Volume 70 / Issue 3 / Summer 2016

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 30 May 2016, pp. 551-586

- Print publication:

- Summer 2016

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Feudal Revolution and Europe's Rise: Political Divergence of the Christian West and the Muslim World before 1500 CE

-

- Journal:

- American Political Science Review / Volume 107 / Issue 1 / February 2013

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 January 2013, pp. 16-34

- Print publication:

- February 2013

-

- Article

- Export citation

Religiosity-of-Interviewer Effects: Assessing the Impact of Veiled Enumerators on Survey Response in Egypt

-

- Journal:

- Politics and Religion / Volume 6 / Issue 3 / September 2013

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2013, pp. 459-482

-

- Article

- Export citation

Bahgat Korany. The Changing Middle East: A New Look at Regional Dynamics. Cairo and New York: American University in Cairo Press, 2010. x + 282 pages. Cloth US$29.95 ISBN 978-9-774-16353-1.

-

- Journal:

- Review of Middle East Studies / Volume 46 / Issue 1 / Summer 2012

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 March 2016, pp. 125-127

- Print publication:

- Summer 2012

-

- Article

- Export citation

Elite Competition, Religiosity, and Anti-Americanism in the Islamic World

-

- Journal:

- American Political Science Review / Volume 106 / Issue 2 / May 2012

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 17 May 2012, pp. 225-243

- Print publication:

- May 2012

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Autumn of Dictatorship: Fiscal Crisis and Political Change in Egypt under Mubarak. By Samer Soliman. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011. 224p. $80.00 cloth, $22.95 paper.

-

- Journal:

- Perspectives on Politics / Volume 10 / Issue 1 / March 2012

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 March 2012, pp. 205-206

- Print publication:

- March 2012

-

- Article

- Export citation

Anne Marie Baylouny, Privatizing Welfare in the Middle East: Kin Mutual Aid Associations in Jordan and Lebanon (Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 2010). Pp. 316. $70.00 cloth, $26.95 paper.

-

- Journal:

- International Journal of Middle East Studies / Volume 43 / Issue 3 / August 2011

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 26 July 2011, pp. 583-585

- Print publication:

- August 2011

-

- Article

- Export citation

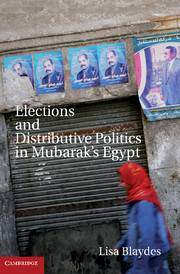

5 - Electoral Budget Cycles and Economic Opportunism

-

- Book:

- Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt

- Published online:

- 04 February 2011

- Print publication:

- 22 November 2010, pp 77-99

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Egypt in Comparative Perspective

-

- Book:

- Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt

- Published online:

- 04 February 2011

- Print publication:

- 22 November 2010, pp 210-236

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Elections and Elite Corruption

-

- Book:

- Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt

- Published online:

- 04 February 2011

- Print publication:

- 22 November 2010, pp 125-147

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt

-

- Published online:

- 04 February 2011

- Print publication:

- 22 November 2010

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt

- Published online:

- 04 February 2011

- Print publication:

- 22 November 2010, pp 245-274

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt

- Published online:

- 04 February 2011

- Print publication:

- 22 November 2010, pp 237-244

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt

- Published online:

- 04 February 2011

- Print publication:

- 22 November 2010, pp 1-25

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Export citation