Introduction

Why do states intervene in the foreign takeover process even within the context of security communities based on economic liberalization and integration? In this chapter, I resolve this puzzle by recognizing that state intervention into cross-border M&A can be understood as a tool of statecraft. I develop a model that explains when, how, and why states use intervention into foreign takeovers strategically to balance the power of other states.

This chapter has five components. In the first section, I examine the link between national security and foreign takeovers, providing a necessary backdrop to understanding how and why intervention into cross-border M&A acts as a tool of statecraft. This part of the chapter outlines how states approach national security in relation to foreign takeovers, the legal and regulatory systems they use for restricting such investment on these grounds, and the common types of national security risks states associate with cross-border M&A. The second section examines the relationship between economic interdependence and power, and why the distribution of economic power within the international system matters to states. It looks at the theory behind the potential for increased economic competition among interdependent states, how some states act strategically to exploit economic interdependence to their advantage, and why states might seek to balance rising economic and military powers in the economic sphere. In the third part of the chapter, I provide a detailed outline of my theory of non-military internal balancing and how it relates to intervention into foreign takeovers. I also propose a probabilistic theory of when and why states are most likely to use intervention into cross-border M&A as such a tool of statecraft, and examine the different forms that such intervention may take in practice. This allows me to offer a solution to the puzzle of why this particular tool of non-military internal balancing is used within security communities. The fourth section then details the hypotheses that underpin my theory, and provides a detailed overview of the methodology used to quantitatively and qualitatively test these hypotheses throughout the book. I conclude with a brief discussion of the expected results of these tests, and of the significance of these findings.

National Security and Foreign Takeovers

States reserve the right under international law to block foreign investments on national security grounds. This right is part of customary international law and is frequently “recognized in various international agreements, in countless bilateral investment treaties, and in investment chapters of free trade agreements” (Jackson Reference Jackson2013, 7). It is even considered to be the “one notable exception to the open investment policies provided for in the OECD instruments” intended to foster the international liberalization of foreign direct investment (FDI) (Jackson Reference Jackson2013, 7). Thus, despite the overall global trend toward economic liberalization and the reduction of barriers to FDI, this particular right to restrict foreign investment on the basis of national security remains untouched, and its use has surged in recent years (see e.g., Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006; UNCTAD 2016b).

National Security: Understandings and Approaches

For the purposes of this inquiry, national security is understood – at its root – to be that which seeks to maintain the survival of the state and preserve its autonomy of action within the international system. Yet, few states agree on the exact scope of national security in relation to cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A), because what it takes to survive and maintain autonomy varies from country to country depending on a number of factors, ranging from a state's size and resources to its geography and historical context. For example, a 2008 report by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) examined foreign investment restrictions in eleven countries – Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Japan, the Netherlands, Russia, the UAE, the UK, and the US – and found that each one “has its own concept of national security that influences which particular investments may be restricted” by their governments (US GAO 2008, 3). A 2016 report by the OECD Investment Division that surveyed foreign investment policies related to national security in seventeen countries – Argentina, Australia, Austria, Canada, China, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Lithuania, Mexico, New Zealand, Russia, the UK, and the US – came to the same conclusion (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 20–1).

States also have different legal and regulatory approaches to restricting foreign investment on national security grounds. This is due not only to differences in their exact interpretation of the scope of national security, but also to variances in their national legal systems, historical relationships to the market, and “experience with foreign investment” (US GAO 2008, 7). Wehrlé and Pohl (Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016) have categorized these investment restrictions into three broad approaches for the OECD, while making it clear that many states utilize a combination of them.1 The first approach takes the form of “partial or total prohibitions of foreign investment in specified sectors,” which are identified by the state as being integral to national security (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 11, 13–14). This approach focuses on the protection and retention of domestic control over what are often called strategic or national security sectors. The specific industries identified as being strategic vary from state to state, but there are naturally areas of common concern around sectors like aerospace and defense, high technology, and scarce resources. The second approach is for a country to review all proposed investments that fall within certain “legally defined” categories (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 11, 14). The criteria used to delineate these categories usually involve thresholds around the monetary value of an investment, the sector involved, and/or the percentage stake sought in the domestic entity (US GAO 2008). The third approach involves “scrutiny systems that identify individual, potentially problematic transactions,” and then subjects these transactions to review (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 11).2 In the chapters that follow, I focus primarily on the actions undertaken by states as a result of the review and scrutiny of FDI (the second and third approaches), rather than through partial or blanket sectoral prohibitions (the first approach). For, it is through these former approaches that decisions about individual investments are actively taken by a state in relation to a particular foreign investment, and the outcome of that proposed investment is not pre-determined.

Most states are unwilling to explicitly define their understanding of the term “national security” in relation to this type of foreign investment, in order to maintain the flexibility needed to respond to the evolving and context-dependent nature of the threats such transactions might pose. Some states may even use different terminology, referring instead to the need to protect the public order, national defense, or the essential security of the state – though these terms encompass national security (US GAO 2008, 8; Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 20–1). Instead of defining national security (or its surrogate terms), states tend to offer a vague “clarifying definition,” “a list of national security relevant sectors given as examples,” or a discussion of potential illustrative “threats to national security” (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 20–1).3 Despite this ambiguity, some common themes, concerns, and perceived risks are identifiable (Jackson Reference Jackson2013; US GAO 2008; Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016).

National Security Risks and Cross-Border M&A

The US, once again, provides a useful starting point for understanding the nature of the national security concerns that can be raised by foreign takeovers. Despite the classified and confidential nature of individual FDI reviews, the US scrutiny system for vetting foreign takeovers (the Committee on Foreign Investments in the United States, CFIUS) is arguably among the most transparent and institutionalized in the world, and has been written about the most from theoretical, legal, and informational perspectives. And while the US does not define national security for the purposes of foreign investment screening, it does provide an “illustrative,” though not exhaustive, list of the types of “national security factors” the President and CFIUS might take into consideration when assessing whether or not a particular foreign merger or acquisition “poses national security risks” (73 FR 74569). These risks factors are outlined in Section 721(f) of the Defense Production Act of 1950 (DPA) as amended by the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA), codified at 50 U.S.C. App. 2170.4 They include the potential national security effects of a specified transaction on:

domestic production needed for projected national defense requirements,

the capability and capacity of domestic industries to meet national defense requirements,…

the control of domestic industries and commercial activity by foreign citizens as it affects the capability and capacity of the United States to meet the requirements of national security,…

sales of military goods, equipment, or technology to any country…that supports terrorism; [is]…of concern regarding missile proliferation[, nuclear proliferation, or]…the proliferation of chemical and biological weapons; [or]…is identified by the Secretary of Defense as posing a potential regional military threat…

United States international technological leadership in areas affecting United States national security;…

critical infrastructure, including major energy assets;…

critical technologies;…

the long-term projection of United States requirements for sources of energy and other critical resources and material; and

such other factors as the President or the Committee may determine to be appropriate, generally or in connection with a specific review or investigation. (50 U.S.C. App. 2170(f))

This list also includes an assessment of whether or not the transaction is “foreign government-controlled” (50 U.S.C. App. 2170(f)), in the sense that it could lead to “the control of a U.S. business by a foreign government or by an entity controlled by or acting on behalf of a foreign government” (73 FR 74569). If so, or where otherwise appropriate, an assessment is also made of additional risk factors surrounding the country from which the investment ultimately originates, namely: (A) whether or not it adheres “to nonproliferation control regimes”; (B) “its record on cooperating in counter-terrorism efforts”; and (C) whether the transaction could possibly lead to the “transshipment or diversion of technologies with military applications” away from the US, requiring an examination of that country's “national export control laws and regulations” (50 U.S.C. App. 2170(f)).

Even as an arguably benign liberal hegemon, the US recognizes the need to maintain its global technological (and thus military) advantage by pursuing economic policies that foster the health of the defense industrial base, prevent its control by foreign governments, and ensure technology shared with its closest allies is not exported to unfriendly regimes. Undergirding this strategy are the institutions that allow the US government to mitigate or block those foreign mergers or acquisitions it believes to be threatening to national security.5 As the dangers emanating from such deals are numerous, and the risk factors just enumerated can encompass a wide array of specific activities by a foreign investor, it is worth also highlighting those national security threats that Graham and Marchick (Reference Graham and Marchick2006) have identified as being the ones CFIUS frequently considers when assessing a potential foreign takeover in the US. These include a number of specific actions foreign investors might possibly take:

shutting down or sabotaging a critical facility in the United States; impeding a US law enforcement or national security investigation; accessing sensitive data…; limiting US government access to information for surveillance or law enforcement purposes; denying critical technology or key products to the US government or industry; moving critical technology or key products offshore that are important for national defense, intelligence operations, or homeland security; unlawfully transferring technology abroad that is subject to US export control laws; undermining US technological leadership in a sector with important defense, intelligence, or homeland security applications; compromising the security of government and private sector networks in the US; facilitating state or economic espionage through acquisition of a US company; and aiding the military or intelligence capabilities of a foreign country with interests adverse to those of the United States.6

Though both their list and the list provided in the amended DPA focus specifically on US security, they illustrate the types of national security risks that would be of valid concern to almost any country.

Most of these concerns emanate from a state's fear that another state will seek to gain influence over one of its corporations in order to enhance its position and power within the international system. As Graham and Marchick (Reference Graham and Marchick2006, 54) point out, such predatory behavior may include a foreign government using its influence to encourage one of its domestic companies to acquire a foreign company for the purpose of engaging in espionage.7 Even worse, a state might endeavor to acquire a vital component of another country's defense industrial base, which it could then destroy, hijack, or generally use to its advantage. The Chinese government, for instance, has a reputation for trying to buy foreign companies in order to acquire military technology through espionage (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006, 112–13; Interview 2007). Not surprisingly, this behavior has affected the reception of Chinese takeover bids within the US (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006, 112–13; Interview 2007).8 Indeed, the only four foreign acquisitions to be formally vetoed by a US President (since the Exon-Florio legislation that originally enabled a president to do so)9 involved Chinese investors. The first was a Chinese government-owned company (CATIC) that sought to take over a US aerospace components manufacturer (MAMCO) in 1990.10 The second was when, in 2012, the US President ordered a company owned by Chinese nationals (Ralls) to divest four wind farm site assets located in close proximity to restricted military air space (see Obama Reference Obama2012). The third was when the President vetoed the acquisition of the US business of a German semiconductor company (Aixtron) by a Chinese-owned investment fund (Grand Chip) over concerns that Aixtron possessed sensitive technology with military applications and that Grand Chip's bid involved financing supported by the Chinese government (US DOT 2016b). The fourth was when the President vetoed the acquisition of the US-based Lattice Semiconductor by a company (Canyon Bridge) ultimately owned and funded by a Chinese SOE directly linked to China's State Council over a series of national security concerns relating to the Chinese government's involvement in the deal, as well as the technology involved, its use by the US government, and concerns over its continued supply (Baker, Qing, & Zhu Reference Baker, Qing and Zhu2016; US DOT 2017).

Another common concern among many countries is that a state, through entities it either owns or influences, may endeavor to acquire foreign companies in order to increase its control over a valuable resource. Such control could enhance that state's position within the international system by increasing its influence over the behavior of those states that need the resource in question, and which fear an intentional disruption of its supply. The behavior of the Russian government in recent years, which suggests an effort to increase its control over the oil and natural gas industries within Europe in order to augment its influence in the region, illustrates this point well.11

These are but a few examples of the national security concerns states might have in the context of foreign takeovers. One of the reasons the US list is so useful and instructive for understanding the common concerns states may have is that it is rare for states to provide such a rich and detailed set of examples.12 Other countries, when they bother to do so at all, tend to offer more limited examples, but they do often exhibit similar concerns, even though these might be worded differently or use different terminology. The 2016 OECD report, however, offers some examples of factors raised by other countries that are not explicitly covered in the US list. For instance, while the US highlights an investing country's relationship with terrorism as a potential risk, other countries – like France, Italy, Lithuania, and New Zealand – also look at the risk from “investments by persons linked to organised crime,…or other criminal activities” (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 21). Italy considers “investments from foreign countries that do not respect democracy and the rule of law or have held conducts at risk towards the international community” to pose a security risk (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 21). Perhaps more controversially, some countries – like Australia, China, Japan, and New Zealand – highlight concerns regarding “the impact of the investment on the economy” as being among their national security considerations (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 21).

The scope of national security as it relates to FDI will thus vary in accordance with the different threats individual states perceive to their survival and autonomy within the international system. For example, not all governments (or theorists) will necessarily feel comfortable with the inclusion of a foreign investment's impact on the host economy within the remit of national security considerations. However, if a country defines this particular concern publicly as being within the scope of its national security, and then cites a specific foreign investment as being a national security concern for this reason (rather than a national interest concern, which might be more closely identified with the language of traditional economic protectionism), than it will be accepted as a national security concern for the purposes of this book. Defining the exact scope and parameters of “acceptable” or “valid” national security concerns is beyond the book's remit, and should be the subject of a separate inquiry. It is also true that, in rare instances, state officials might use the term “national security” instrumentally (or even inappropriately) in the context of FDI, in order to achieve goals other than balancing. I have therefore assessed the national security grounds cited for intervention (if specified)13 in the cases examined in this book, and have attempted to judge, fairly and without prejudice (insofar as this is feasible), whether the risk cited is in line with a given country's historical approach to national security.

Economic Interdependence and Power

Overall, the types of common national security concerns discussed in the previous section have one clear thing in common. They imply that the state on the receiving end of a particular cross-border merger or acquisition (the target state) believes that the state of the acquirer (the sending state) could be placed at an advantage in terms of military or economic power as a result of that proposed deal, and thus that the transaction could be detrimental to them, the target state. Whether or not the sending state actually intends (or is believed to intend) harm will thus have a great effect on how the government of the target state responds to the proposed transaction.

Clearly, some states do seek to take advantage of the interdependent relationships that arise from globalization, in order to increase their economic and military capabilities relative to others. This notion is well documented (Gilpin Reference Gilpin1981, Reference Gilpin1987, Reference Gilpin2001; Hirschman Reference Hirschman1945; Moran Reference Moran1993; Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh1999; Tyson Reference Tyson1992; Waltz Reference Waltz1993, Reference Waltz1999). And though most theorists of economic interdependence deal with the dependencies that result from foreign trade, rather than FDI, it is a reasonable assumption that these dynamics may be applied to the latter.14 According to these theorists, states will have different levels of “sensitivity” and “vulnerability” as a result of a mutually dependent relationship, where sensitivity implies that a state A can suffer the negative effects of the actions of another state B “before policies are altered to try to change the situation,” and vulnerability implies that state A can be negatively affected by the actions of state B “even after policies have been altered” (Keohane & Nye Reference Keohane and Nye1989, 13).15 Hirschman's systematic examination of such phenomena demonstrates not only that “international trade might work to the exclusive or disproportionate benefit of one or a few of the trading nations,” but also that states may abuse their position in an asymmetrical trading relationship (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1945, 11). He makes the important point that enhancing a state's economic power does “not necessarily lead to an increase in relative power,” or “a change in the balance of economic power in favor of any particular country,” unless states pursue policies that enhance the dependencies of other states on that relationship (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1945, 9).16 As some countries do pursue such policies, states consequently remain concerned with the relative distribution of the gains from trade, even though liberal theorists since Adam Smith have demonstrated the absolute gains to all involved (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1945, 5–6; Keohane & Nye Reference Keohane and Nye1989, 10; Waltz Reference Waltz1979, 140–3).

States are thus highly likely to focus on the relative distribution of economic power within the international system.17 This is especially true in an environment where the likelihood of a major power hot war is low (Mandelbaum Reference Mandelbaum1998/99; Waltz Reference Waltz1993) and hard power within the system must be increasingly gained through non-military means.18 States will therefore seek to increase their economic power, which not only benefits their own domestic economy, but also provides absolute gains to their trading partners, and hopefully increases their ability to influence others by enhancing either their position of dominance or the dependence of other states on their economic policies.19 As a result, “economic competition” will in all probability “become more intense” (Waltz Reference Waltz1993, 59).

A state will thus feel insecure as another state gains economic power relative to it and will seek to balance that rising economic power. Similarly, one state may seek to balance another if the latter attempts to make the former dependent upon it in some way through FDI. When international relations theorists refer to the US backlash against Japanese investment in the 1980s, there is an assumption that this is what occurred. Waltz claims that once Japan recovered from World War II, the US “objected more and more strenuously” to its “protectionist policies” as its economy developed into that of a rising power with a “strategy of ‘creating advantages rather than accepting the status quo’” (Waltz Reference Waltz1979, 7–8). In 1991, Borrus and Zysman suggested that Japan and Europe were both pursuing policies to protect their technological industrial bases from foreign acquisition as part of internal balancing strategies meant to create an eventual advantage over the US (Borrus & Zysman Reference Borrus and Zysman1991, 25, 27). The following year, Tyson strenuously argued for FDI policies that would protect American interests from such Japanese tactics (see Tyson Reference Tyson1992). Graham and Marchick then made a similar argument about the current US backlash against Chinese and Middle Eastern investment in 2006. They asserted that if “the US in the past has sought to protect itself from FDI originating in Germany and Japan,” then “today, similar sentiments are harbored toward Middle Eastern countries for their supposed links to terrorist activities, but more importantly towards China, which, as a vast and growing economy, could one day challenge the US in economic might” (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006, 94). Such an attitude, they believe, can explain US intervention in the Dubai Ports deal and CNOOC's attempt to buy Unocal.

The Theory

Non-Military Internal Balancing and Foreign Takeovers

I believe government intervention into foreign takeovers of companies on national security grounds should thus be understood to be a form of non-military internal balancing, which is primarily motivated by either economic nationalism or pressing geostrategic concerns. This theory begins from neorealist assumptions about the structural dynamics of the international system and its general effect on state action. Yet, as structural realism alone cannot provide the full solution to our puzzle, it is also necessary to include certain domestic-level variables, such as the presence of economic nationalism, in our investigation.

This combination of domestic and structural variables with a primary focus on the structure of action can be likened to a neoclassical realist approach. Neoclassical realists “argue that the scope and ambition of a country's foreign policy is driven first and foremost by its place in the international system and specifically by its relative material power capabilities” (Rose Reference Rose1998, 146). Yet, they also believe “that the impact of such power capabilities on foreign policy is indirect and complex, because systemic pressures must be translated through intervening variables at the unit level” (Rose Reference Rose1998, 146). It is for this reason that neoclassical realists, such as Schweller, Wolforth, and Zakaria, examine both domestic and system-level variables to explain foreign policy outcomes (Lobell et al. Reference Lobell, Ripsman and Taliaferro2009, 20). Such theorists build on both the insights of structural realism, because of its appreciation of systemic pressures placed upon state actors, and classical realism, because it recognizes “the complexity of statecraft” (Lobell et al. Reference Lobell, Ripsman and Taliaferro2009, 4). Importantly, these theorists demonstrate that the “‘transmission belt’ between systemic incentives and constraints,…and the actual diplomatic, military, and foreign economic policy of states” is “imperfect” (Lobell et al. Reference Lobell, Ripsman and Taliaferro2009, 3). Schweller, for example, has used domestic political variables to explain why, within the context of balance of power theories, states might underbalance a rising threat. In other words, the neoclassical realist understands that “decision makers are not sleepwalkers buffeted about by inexorable forces beyond their control” but actors who “respond (or not) to threats and opportunities in ways determined by both internal and external considerations of policy elites who must reach consensus within an often decentralized and competitive political process” (Schweller Reference Schweller2004, 164). They recognize that international relations is a two-level game (Putnam Reference Putnam1988), and believe that an examination of the domestic variables that motivate states to recognize, and implement, structurally demanded strategies should not be degrading to realist theory, but should instead contribute to its progress in the Lakatosian sense (Lobell et al. Reference Lobell, Ripsman and Taliaferro2009, 21).20

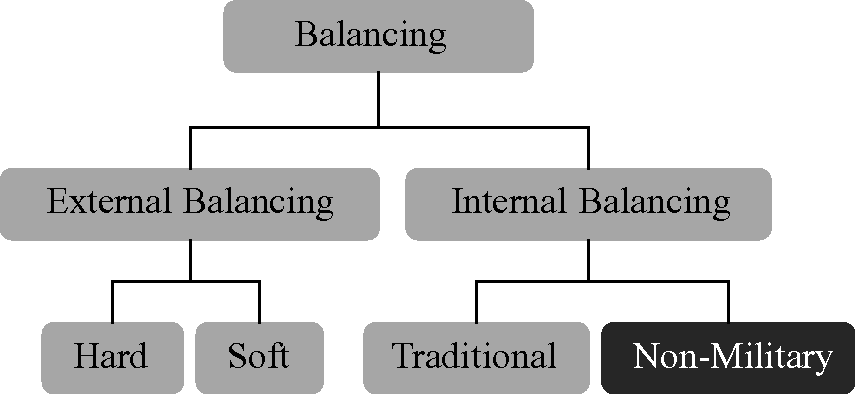

The theory presented in this book begins from the structural realist assumptions that states are the primary actors21 in an anarchic international system and that, as such, they must rely on themselves to provide for their own security and survival (Waltz Reference Waltz1979, 88–93). This focus on survival within the context of a necessarily “self-help system” causes states to be concerned with the relative distribution of power, defined primarily on the basis of “capabilities” (Waltz Reference Waltz1979, 97–9, 129). As a result, states will seek to maintain or maximize their power relative to that of others, either when threatened (Walt Reference Walt1987)22 or when their relative power is challenged by an actual and unfavorable change in the distribution of capabilities (Waltz Reference Waltz1979, 118). According to Waltz, a state may balance the relative power of another either externally, through “moves to strengthen and enlarge one's own alliance or to weaken and shrink an opposing one,” or internally, through “moves to increase economic capability, to increase military strength, [and/or] to develop clever strategies” (Waltz Reference Waltz1979, 118) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Modes of balancing

Government intervention into cross-border M&A can thus be understood to be a tool of internal balancing. It can certainly be part of an effort to preserve or enhance domestic economic capability and/or military strength, when the outright takeover of a particular domestic company challenges, or threatens to alter, the state's relative possession of those capabilities. For, states may use intervention to protect companies (or some of their assets and capabilities) from foreign control, when that control is sought for purposes that would prove detrimental to state security. States may, for example, attempt to block or alter a foreign takeover in order to preserve (and sometimes further) technological and industrial advantages that are vital to their military power, or to the resources necessary for their continued existence. Similarly, states have also used intervention to protect national champions deemed vital to their economic power and position. It will be demonstrated in the chapters that follow that most examples of government intervention into foreign takeovers on national security grounds, and in the sectors commonly associated with national security examined in this book, are acts that seek to maintain or maximize the economic and/or military power of the state in response to a threat or challenge to that power posed by the takeover. In other words, the form, intent, and purpose of such interventions are clearly consistent with those of internal balancing, as it is traditionally understood.23

The scope of Waltz's definition of internal balancing is indeed wide enough to encompass such government action. For, though many scholars have come to simplify the definition of the term to refer only to the mobilization or enhancement of arms and other military capabilities,24 the economic element should not be forgotten, especially as it is often integral to the success of the defense industrial base that oils the machine of war. In an effort to further specify the role of economic policy in balancing, Brawley argues that there are clearly separable economic and military components of both internal and external balancing (in Paul et al. Reference Paul, Wirtz and Fortmann2004).25 Though his discussion of the economic component of internal balancing revolves primarily around basic trade and financial aid strategies, there is no reason why it might not include strategies for dealing with FDI in sensitive industries or companies of the type examined here. Borrus and Zysman, for example, have claimed that Waltzian internal balancing can be synonymous with “positive industrial adjustment” of the type used by states to gain a competitive economic and military advantage in terms of technology, which they mention can – beyond the trade and industrial policies usually discussed in that context – involve policy that either prevents foreign acquisitions in some sectors or places “local content requirements” on other forms of FDI (Borrus & Zysman Reference Borrus and Zysman1991). There is thus some precedent for the argument that the behavior examined in this book can act as a type of internal balancing.

Furthermore, I argue that state intervention into foreign takeovers acts – more particularly – as a form of non-military internal balancing. Here, the strategy still involves strengthening military and/or economic capabilities, but also has two important non-military elements. First, the tool is clearly one of policy and action that occurs within the context of the economic realm. Second, non-military internal balancing involves actions that seek to enhance a state's relative power position vis-à-vis another state, or states, without severing the greater meta-relationship at stake between those states. The goal is still to balance a challenge or threat to power through non-military and internal means, but, unlike Brawley's concept of the economic component of internal balancing, non-military internal balancing is classified by this additional objective of state behavior, as well as by the type of conduct used to achieve those objectives.

It is also important here to clearly differentiate non-military internal balancing from soft balancing, as some important distinctions exist between these two concepts (see Figure 3). First and foremost, non-military internal balancing is a strategy that may be employed by both hegemonic and weaker powers, whereas soft balancing is usually defined as a policy tool that is only used against a hegemon (see Pape Reference Pape2005; Paul Reference Paul2005; Walt Reference Walt2005). This is because much of the literature on soft balancing arose out of a desire to explain why states in the post-Cold War period had not formed a countervailing military coalition against US hegemonic power in the way many international relations theorists expected, as well as to categorize the non-military and non-traditional efforts of many states to constrain (or restrain) US unilateralism in the wake of 9/11.26 These theorists believed “it was a mistake” for structural realists “to expect ‘hard balancing’ to check the power of the international system's strongest state” after the end of the Cold War because in a unipolar system, “countervailing power dynamics [would] first emerge more subtly in the form of ‘soft balancing’” (Brooks & Wolforth Reference Brooks and Wolforth2005). Nye, however, has made a compelling case that while the world might be unipolar in the military realm (and this itself may be changing, with the rise of Russian and Chinese forces in recent years), it is clearly multipolar in the economic one (Nye Reference Nye2002, 39). If one accepts this, then traditional methods of internal balancing are even more likely to occur in the economic realm than soft balancing theorists currently recognize, and, more importantly, a military hegemon may engage in the same type of non-military internal balancing behaviors as weaker states. This is clearly the case now, as the US seeks to preserve its relative power position through non-military internal balancing against rising powers, just as Italy or Russia might use similar techniques to enhance its own position.

Second, most definitions of soft balancing are based on the policy tools states employ, rather than on the policy objectives they seek (as with Brawley's concept of the “economic component” of internal balancing). Paul, for example, defines soft balancing as “tacit balancing short of formal alliances…often based on a limited arms buildup, ad hoc cooperative exercises, or collaboration in regional or international institutions” (in Paul et al. Reference Paul, Wirtz and Fortmann2004, 3). This explains why theorists like Pape (Reference Pape2005) argue that such strategies could eventually lead to hard balancing in the future. The concept of non-military balancing, however, is defined by its ends as well as by its means. Finally, only a few soft balancing theorists even mention that the use of economic tools might be part of an act of soft balancing (see e.g., Pape Reference Pape2005; Paul Reference Paul2005; Walt Reference Walt2005), and even fewer provide rigorous empirical testing of their claims regarding the economic forms of soft balancing. Thus, while non-military internal balancing might be used in tandem with soft balancing under certain circumstances, it must be clearly differentiated from that concept.

Government intervention into foreign takeovers acts as an excellent form of non-military internal balancing because it allows states to provide for their long-term security in a way that takes full advantage of their present power position without causing them to engage in activities that are viewed as inherently confrontational.27 States are therefore able to both “maximize value in the present” and “secure their future positions” through economic competition (Waltz Reference Waltz1993, 63), without other states necessarily perceiving that build-up as being targeted against them. Again, this is especially relevant in an international environment where the inter-state use of force is less acceptable. It also helps to explain why allies might engage in such a form of balancing against one another, i.e., this strategy allows states to jostle for position within an alliance, as well as to provide for their long-term security should the strength of the alliance eventually deteriorate.28 This is because there is a prevailing perception that, while states intervene in foreign takeovers for the “high politics” reason of national security, the act and its effects occur in the “low politics” realm of bureaucrats and businessmen.29 This perception can, in many cases, actually help the state to maintain valuable relations with the other country involved in the transaction. For, even when heads of state do become involved in a foreign takeover process, the professed desire to protect companies, resources, and technology deemed vital to national security is so old and inherent that it is rarely taken “personally” by other states. On the rare occasion that the acquiring company's host state is offended, its government may find it difficult to express such offense at the official level without risking constraining its own future breadth of action.30

Government intervention into foreign takeovers also serves as a highly flexible tool for non-military balancing, because of the numerous forms it can take. For, though formal government vetoes of foreign takeovers are the most well-known form of intervention, they are also the rarest. Instead, interventions usually tend to range from alterations to the deal (mitigation measures) that allow the host state of the target company to retain control over its domestic security, to informal government intervention that causes the acquiring company to withdraw voluntarily from the process in order to save “face” or money. Thus, many forms of intervention do not, on the surface, appear to “block” a deal, nor do they make it look as if a government has taken negative action against another state. Instead, its action is cloaked within the deal process. This assuages negative feelings between both countries and helps preserve the relationship between them, while still allowing one state to pursue a gain in relative economic power. It also permits governments to preserve their relative economic and military power vis-à-vis another state by helping them maintain domestic control over those industries, resources, and companies that they consider vital to national security.

While these arguments explain why states balance economic power through a strategy of non-military internal balancing, they do not necessarily answer the puzzle of why governments would treat members of their own security community in the same way as those outside of that community. For, though it may be obvious to a realist why America would choose to balance a rise in Chinese economic power, the motivations behind a European state's desire to balance the rise in economic power of another European state (within the context of both an economic and a security community) are not as obvious. As mentioned earlier, structural realism does not account for why a state would engage in such behavior against its military allies, or how that balancing of economic power might vary according to motivation and context.

The rest of the theory presented here attempts to resolve these issues by arguing that the answer lies in the form of government intervention that non-military internal balancing takes, which will vary in accordance with its primary motivations. A probabilistic theory of intervention (laid out in the next section) is followed by an examination of the possible solution to the puzzle, and later by the hypotheses that will be examined in this study to verify the soundness of that argument.

A Probabilistic Theory of Intervention

Before moving to the solution of the puzzle, it is necessary to first provide a general and probabilistic theory of when and why governments are likely to intervene in foreign takeovers on national security grounds. As mentioned already, non-military internal balancing is primarily motivated by either geopolitical concerns or economic nationalism. However, alternative explanations must be controlled for, including economic and interest group arguments. Thus, the principal hypothesis examined in this book is that an individual government's use of domestic barriers to foreign takeovers of companies on national security grounds depends on (1) the geostrategic implications/concerns raised by the potential takeover and (2) the level of economic nationalism in the target company's home state, controlling for (3) the economic competition concerns raised by the potential takeover and (4) the presence of interest groups that oppose the acquisition of the target company and have access to power in the home state of that company.

The use of case studies allows for a detailed exploration of the various nuances and different dimensions of these variables. Toward this end, the following definitions were used in the investigation of the case studies, though narrower ones were necessary for the purposes of the statistical investigation of this hypothesis, as discussed in Chapter 2.

The presence of geopolitical competition between states will be determined qualitatively on the basis of three factors. The first will be the degree to which the character of the political relationship between the countries involved in the transaction is positive or negative. In other words, are the two countries formal military allies? If so, are they members of the same security community? Does the potential for strategic competition exist between those countries? Even if states A and B31 are allies, is there a prevailing perception within state A that state B is a threat? The second factor is the degree of resource dependency between states A and B. In other words, what is the general level of state A's dependence on trade to obtain basic resources such as oil, natural gas, and water? Furthermore (to the extent that information is available), what is the specific level of state A's dependence on state B for these resources? The third factor is the differential in relative power between the two states involved in the transaction. Is the host state of the acquiring company a major power? Is the host state of the target company a major power? Is state B rising in relative economic power to state A? Is it increasing in military power?

The presence of economic nationalism in state A will be determined on the basis of three factors. The first will be the level of national pride that the populace of state A professes to have. The second will be the level of anti-globalization sentiment within the populace of state A. The third will be the level of domestic support for companies that are considered “national champions.” In other words, is the target company often referred to in public parlance as a “national champion”? Does state A demonstrate support for national champions in other cases?

The remaining variables represent two possible alternative explanations of government intervention for which this study will need to control. The first is that the specific form of economic protectionism being examined here may be explained by the presence of interest groups pressing for governmental intervention. The case studies will, therefore, seek to identify the presence of individual pressure groups that were involved in the process, and determine their effectiveness in changing the policy of the government in question vis-à-vis the potential takeover.

I expect to find, however, that while interest groups may raise the awareness of state A regarding national security issues raised by state B's involvement, or company Z's behavior, this is unlikely to be the cause of intervention. In other words, states will tend to formally intervene (either to block or alter a deal) only when national security issues are actually present, because of the reputational concerns involved. If we look to the US, for example, it seems that while there is occasionally evidence of a pressure group raising the government's awareness of a deal, once that awareness is raised, pressure groups are largely kept out of the process.32 As governmental decisions in this area seem to fly in the face of interest group pressure as often as they agree, the results of the hypothesis testing are expected to show little or no correlation to this variable.

The second alternative explanation for government intervention is that the merger or acquisition was blocked on the basis of competition concerns raised by either the host state of the target company, the host state of the acquiring company, or a relevant regional economic authority, such as the EU Commission. Each case will be examined to see if the relevant state (or regional) authority raised competition concerns. This variable is included in the case studies as a control variable, because of the possibility that government review of a given deal might be precluded by a decision that the takeover should be blocked on competition grounds.

It should be noted that other alternative independent variables were considered during the formative stages of the theory presented here. These ranged from additional domestic politics variables, such as the role of electoral politics and racism in government interventions, to the presence of competing bidders and some of the potential ownership structures of the acquirer involved in individual transactions. As my aim is to create as parsimonious a theory as possible on a complex subject, I ultimately decided not to include these variables, which in preliminary testing and research proved insignificant across the body of cases and whose inclusion, even as controls, did not appear to improve the explanatory power of the case studies or the fit of the statistical model. (For further discussion of these variables, and why they were not included in the final hypotheses tested, see Appendix A.)

If the sole purpose of this inquiry were to predict the likelihood of intervention in any one particular case, it would be necessary to formulate my argument differently. For instance, Grundman and Roncka have created a comprehensive “risk assessment matrix” to help determine the chances of a US government intervention into a given cross-border merger and acquisition (Grundman & Roncka Reference Grundman and Roncka2006, 8). They suggest twenty possible variables that might affect a company's chance for survival of the government review process. To name but a few, these include general economic and political variables such as: whether or not the deal is “beneficial to current US customers”; the “viability of current US ownership”; the “amount of media coverage”; and the “lobbying strength of competing bidders” (Grundman & Roncka Reference Grundman and Roncka2006, 8). Others are focused on how the deal affects the health of the defense industrial base, including: the benefit to the US in terms of the “net technology transfer”; the “requirement for interoperability with the US”; whether or not the “target firm's business” is “commercial” or “defense” related; and whether the target's “level of classification” is “unclassified” or one of “special access” (Grundman & Roncka Reference Grundman and Roncka2006, 8). Additional variables focus on the national security concerns germane to this inquiry, namely: whether or not the “partner country is [a] US ally”; the degree of “foreign ownership,” or “foreign government ownership” or “influence”; whether or not the host state of the acquiring company (or the company itself) has “ties to ‘unfriendly’ entities”; and the degree to which the “political climate” is “hostile” to the deal (Grundman & Roncka Reference Grundman and Roncka2006, 8). Clearly, checking off every item on this extensive list of factors is vital for companies engaging in the US review process.

The goal of this book, however, is to offer a theory that is both parsimonious and generalizable, rather than one that is deeply US (or case) specific. Thus, while it is necessary to draw on the work of analysts like Grundman and Roncka, it is also important to ascertain whether or not some of the specific variables they examine might fit into broader categories, or drop out all together. It must be stressed again that the purpose here is to delineate probabilistic tendencies toward state intervention across countries, cases, and time. I recognize that states, and the bureaucrats within those states who deal with these issues on a daily basis, approach each foreign takeover as an individual case, and may not even be cognizant of the overarching tendencies in their behavior. I also recognize that many different actors – from bureaucrats and parliamentarians to heads of government – ultimately contribute to a state's final position or stance regarding intervention, and thus all relevant government actors are examined in each case studied in this book.33 Yet, what is ultimately being investigated here is how the environment in which states must act, on the whole, structures the action of those states in each case, given the presence of the variables outlined in my hypothesis.

The Solution to the Puzzle

Such a probabilistic theory of intervention alone cannot explain the puzzle of why states utilize domestic barriers to foreign takeovers of companies in national security industries, even within security communities founded on economic liberalism and integration.

One way to solve the puzzle is to argue that not all forms of non-military internal balancing through government intervention into M&A on national security grounds can be considered equal. Rather, as in all forms of balancing and power competition, there are variations on the theme that can achieve the same desired effect. State A may thus be able to ensure the protection of its national security, and even preserve its long-term power objectives relative to state B, by simply altering or mitigating the effects of an M&A deal in some way. This is a more likely option among close allies, especially where some degree of integration of the defense industrial base is preferable, because it widens the scope of competition and enhances opportunities for the development of new technologies, while likely lowering prices. Thus, while governments will intervene in cross-border takeovers by allies, that intervention may be more likely to lead to a “changed” deal that protects national security, rather than a “blocked” deal.

Most instances in which deals are blocked will result from geostrategic concerns that arise between countries that are either not allied, or between whom there have arisen issues of trust despite the existence of an alliance relationship. It must be noted that there are examples of even the closest of military allies finding that companies within their state (which they may or may not be connected to) are having their proposed takeovers “effectively” or formally blocked. I argue that this can occur when the host state of the acquiring company, or the acquiring company itself, is viewed as significantly threatening. Some flexibility is required in determining what poses a significant enough threat to lead to a breakdown in trust between two countries; it could range from fears of espionage to a negative perception of the other state arising from actions in the realm of national security, despite the existence of a formal military alliance between those states. As one source within the legal community has pointed out: “there are allies, and there are allies” (Interview 2007). Which “friends” are the most trusted, and in what areas they are trusted, soon becomes quite clear to those looking at government intervention into cross-border M&A.

Forms of M&A Intervention as Non-Military Internal Balancing

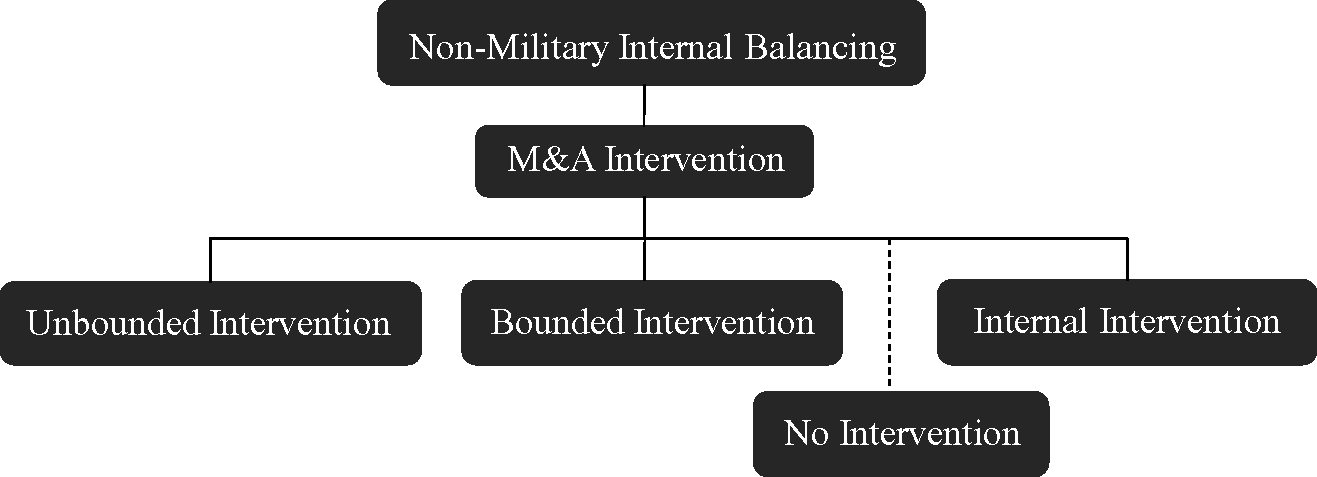

I argue that government intervention into cross-border M&A can be considered to take three possible forms, which are classified here as unbounded, bounded, and internal intervention (Figure 4). Each of these forms is defined in this section, as are the conditions that may allow a deal to proceed with little or no intervention. However, in most of the sectors considered by states to be integral to national security, it is extremely rare for a deal not to face some level of mitigation or alteration before it is allowed to go through.

Figure 4 Types of M&A intervention as a tool of non-military internal balancing

Unbounded Interventions

Unbounded interventions are those in which the intended result of government intervention is the formal, or effective, block of a cross-border merger or acquisition as a consequence of stated concerns regarding national security. A “formal block” occurs when the government, or one of its representative agencies, announces that a deal has been vetoed on national security grounds. An “effective block” occurs when the acquiring company withdraws or rescinds its proposed bid for the target company as a result of one or more of the following actions:

1. The government (and/or its agencies) voices such significant concerns or reservations regarding the deal before the formal review process begins that the acquiring company feels compelled to withdraw its bid in the face of “overwhelming opposition” that would be costly to overcome.

2. The part of the deal involving the target state or a third-party state involved in the transaction has, for all intents and purposes, been vetoed through either a forced divestiture of the facilities/subsidiaries in its country or through some other similar means.

3. A lengthy review process is undertaken, from which the company does not believe its bid will emerge successfully, either because

a. The review process has extended in time to a point where it is proving too costly for the company to proceed,34 or because

b. The government has indicated to the company that it is unlikely to emerge from the process successfully.

Anonymous sources confirm that in the US, for example, CFIUS and/or its member organizations will indicate to a company whether or not it is likely to emerge successfully from a CFIUS review or investigation. This is one of the reasons why the number of withdrawals during the review/investigation process is exponentially higher than the number of vetoes.35 It is possible that an effective block might not initially succeed in stopping the parties involved in a transaction from trying to conclude a particular deal. However, a state can still formally veto a deal if an effective block fails. If the companies involved fail to notify the relevant national authorities before a transaction is completed, many countries also maintain the right to review the takeover after completion, and to unwind it (in whole or in part) if it is deemed to pose a threat to national security.

“Unbounded” opposition is usually motivated by geopolitical concerns, and involves companies that state A is concerned with protecting on national security grounds. In the US, these will often be the most highly politicized cases, as interest groups may be able to prey more effectively on post-9/11 sensitivities to national security. It is important to note again, however, that while interest groups might raise the alarm about a deal, they will rarely affect its outcome. It is also possible that some of these cases will simultaneously raise competition concerns in other government agencies – agencies that might seek to veto the deal on those grounds instead. It is therefore important to control for such alternative explanations of intervention as the hypothesis is being tested.

Bounded Interventions

Bounded interventions are considered to be those that result in deals that the government has been able to alter in its favor through some means or another. Though the effect of interest groups and competition concerns will be controlled for, it is usually expected that “bounded” balancing will most often be motivated either purely by the national security concerns raised by the geopolitical competition context of the case and/or by economic nationalism surrounding companies in the sectors associated by the state with national security. It is also expected that in the latter case, states may closely identify “national security” with “economic security.”

In the US, for instance, mitigation may take a couple of different broad forms. Graham and Marchick, for example, note that “if the DOD believes that the risks [to national security] it identifies can be managed, it may also negotiate mitigation measures with the transaction party,” which “generally fall into four categories (in ascending order of restrictiveness)” (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006, 71). These are “board resolution,” “limited facility clearance,” a “Special Security Agreement (SSA)”36 or “Security Control Agreement (SCA),”37 and a “voting trust agreement” or a “proxy trust agreement”38 (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006, 71–2).

One recent CFIUS decision, concerning the Alcatel/Lucent deal (examined in Chapter 5), also made it clear that new forms of mitigation may be emerging. In the review of that takeover, the US included an “evergreen” clause as part of the security agreement between itself and the companies involved, which basically means that the US government retains the right to force a reversal of the deal at any point in the future if it discovers that Alcatel has not lived up to its promises regarding measures to safeguard US national security.39 Members of the legal community have indicated their belief that such a clause has never been used before in a US security agreement regarding a cross-border acquisition (Interview 2007). It should also be noted that forced divestitures, while not common in the US, do occur there and in other countries as a form of mitigation. (For further discussion of the different types of mitigation used in the US and abroad, see Chapter 5).

Though there are many different forms that mitigation may take, and these forms vary by country, the US forms of mitigation will be used as the standard, as they are the most highly institutionalized and the most is known about them. Similar phenomena will be looked for in the other countries in order to determine whether or not a deal has been altered. That being said, the actual existence of most of these forms of mitigation in an individual case is meant to be confidential, and their content is usually classified. Thus, we will only know of the existence of these forms of mitigation if they have been made public through a press release issued by one of the companies in question, or if news of their existence has been leaked to the press or other open-source intelligence outlets. This will obviously skew any statistical results away from the correlation that this study seeks to find between mitigation and the variables proposed here. This is an acceptable reality, however, as it means that we can largely assume that any correlation found is likely to be much stronger than the statistical results indicate.

One of the reasons why we are more likely to see bounded intervention among the allies of the Western security communities (meaning the transatlantic partnership and the EU) is because the process for the review of cross-border M&A is more highly institutionalized among the Western advanced industrial states. Indeed, it is most highly institutionalized in the US, which is why the US is where we should expect to see the lowest level of interest group influence on outcomes of the review process. The process is less institutionalized within Europe, but still much more advanced than it is in, say, Russia or China, where there is very little transparency about the review process. Higher levels of institutionalization allow allies to find alternative solutions to national security concerns, beyond simply prohibiting a deal or evidencing such overwhelming opposition that the proposed acquirer voluntarily withdraws from the process. Beyond the more closed natures of their markets and the risks they pose for investors, such differences in institutionalization may also contribute to the extremely low levels of cross-border deals in Russia and China for the sectors discussed in this book.

Non-Intervention

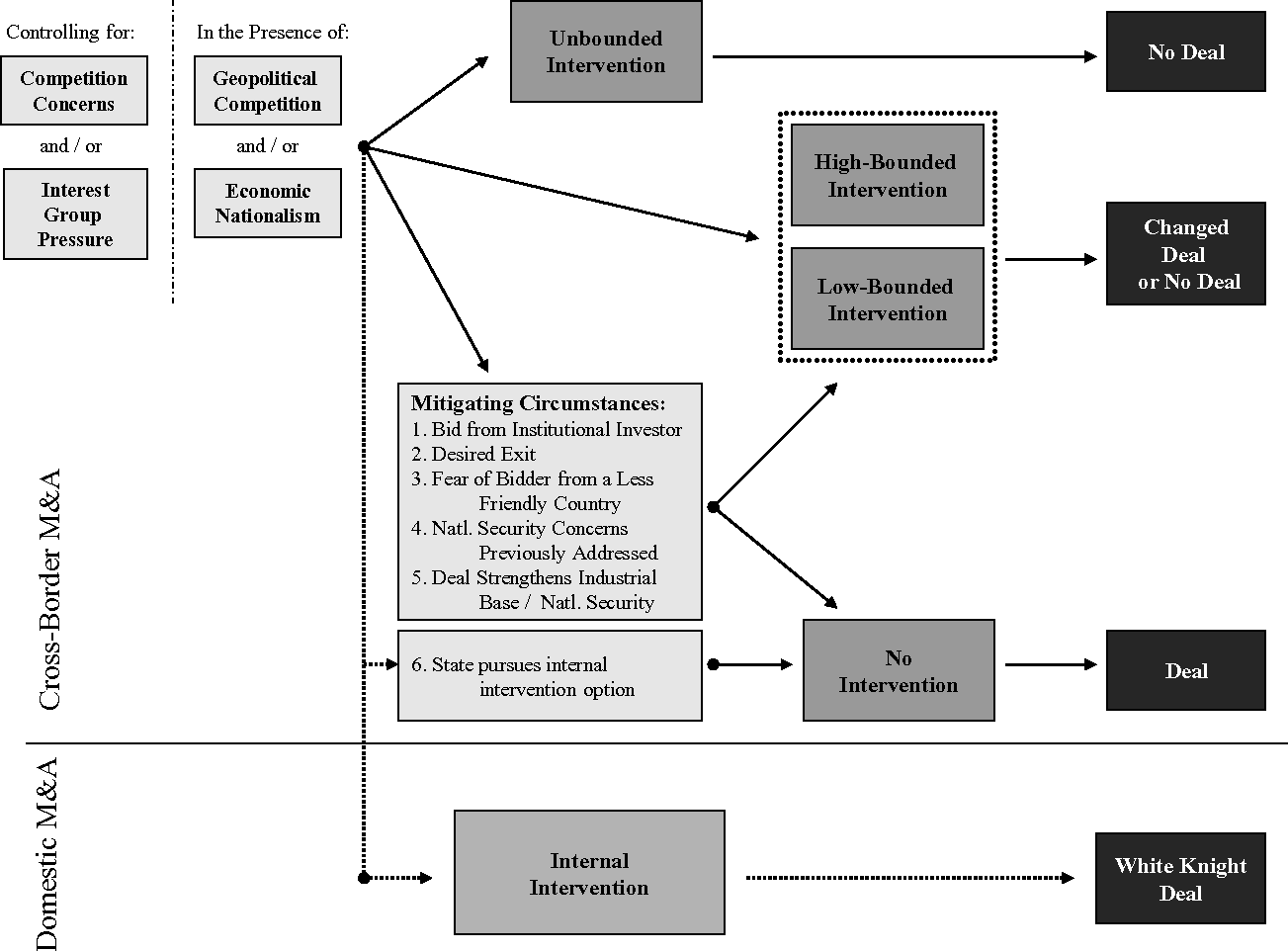

The following circumstances allow a proposed deal, that would normally be mitigated, to go through without any visible intervention (Figure 5). (Again, it must be noted that some of those deals that seem to go through without intervention may have actually been mitigated in some way by the host state of the target company, but, due to the classified nature of that mitigation, it may not be possible to tell.)

Figure 5 Non-military internal balancing through M&A intervention

Note: This diagram illustrates the intervention options a state might pursue when it believes a specified cross-border M&A transaction could pose a risk to national security.

First, if the bid for the target company comes from an institutional investor40 based in a foreign country, or a consortium of institutional investors from multiple countries, intervention may be less likely. Here, it is expected that the deal will be more likely to go through, because institutional investors are generally viewed as more focused on profit than politics, and are also viewed as being largely independent from government control or influence. Exceptions may occur: for example, when governments fear that an institutional investor will run the company into the ground, or sell the company in question to an unfriendly country.

Second, there may be a reduced probability of intervention if the deal in question involves a company that the government wishes to be sold, i.e., the sale is a “desired exit,” and there is a realization that it cannot be sold domestically. In this case, the cross-border deal is less likely to face intervention if the sale can be made to a handpicked friendly country.

Third, a deal that may have initially faced strenuous opposition from the government may suddenly be welcomed if another, less-desirable company is rumored to be making, or actually announces, a bid for the target company. In other words, imagine that state A initially opposes a bid for company X by a company Z from state B (which is neither a true ally, nor an enemy). Then, a company Y, influenced or controlled directly by state C (with whom state A is on a less friendly footing), is known to be contemplating a bid for X. The fear of the bidder from state C may very well cause state A to withdraw its opposition to the initial bid by state B (see, e.g., the Arcelor/Mittal deal in Chapter 6).

Fourth, a deal may face little or no opposition if the national security concerns that would normally be raised have been previously addressed in some way. An example of this in the US would be if the company in question had already negotiated a special security agreement for the type of deal at hand, and the government did not feel that it needed to negotiate a new one. (As discussed in Chapter 6, BAE Systems serves as an excellent example of a company that has benefited from already having a comprehensive security agreement with the US government.)

Fifth, a deal may face little or no intervention if it is considered to be advantageous to the defense industrial base in some way, or is perceived to be advantageous to national security.41 The deal might, for example, increase the competition among companies in the production of a good vital to national security (such as semiconductors), or provide the state in question with access to a resource that it desperately needs.

Finally, (un)bounded intervention into a particular proposed foreign takeover may prove unnecessary if the option of internal intervention is pursued, obviating the need for such direct intervention. This concept is explained in the following section, and again more fully in Chapter 6.

Internal Intervention

Internal intervention is an alternative for governments seeking to protect a specific company from a foreign takeover. It usually occurs when a company considered by the government to be vital to national security (and possibly to be a national champion) is deemed to be a vulnerable takeover target by the market. Rather than waiting for a bid that may potentially come from an unfriendly source, the government in question proactively seeks a domestic alternative. This may mean that the government actively encourages another domestic company to take over (or merge with) the vulnerable company, or that it encourages domestic investors, companies, or government-backed entities to purchase a large stake in the company in order to promote a high level of cross-shareholding that makes a foreign takeover more difficult.

Methodology

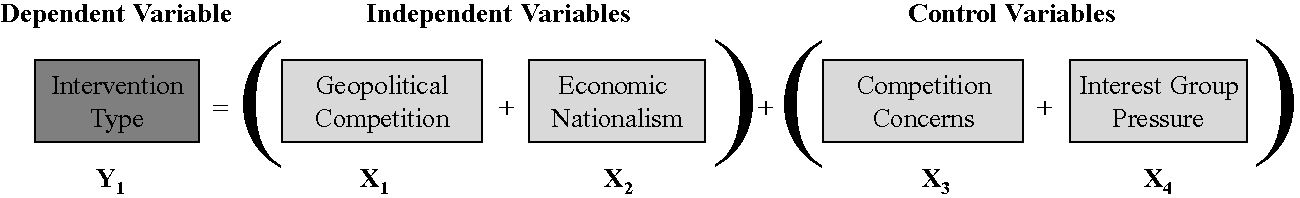

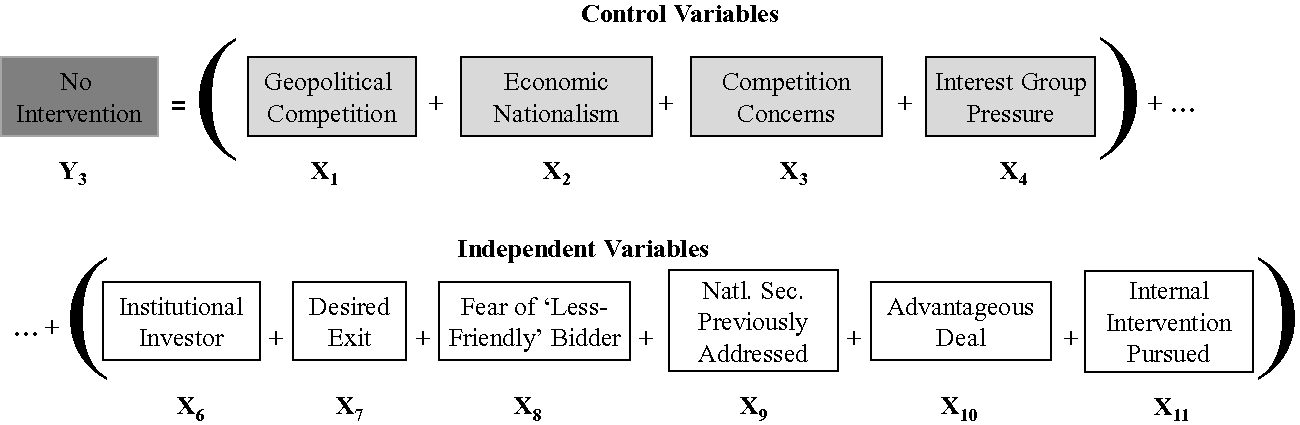

Three hypotheses emerge from this theory. The primary hypothesis tested here is that government use of domestic barriers to foreign takeovers of companies on national security grounds depends on (1) the geostrategic implications/concerns raised by the potential takeover and (2) the level of economic nationalism in the target company's home state, controlling for (3) the economic competition concerns raised by the potential takeover and (4) the presence of interest groups with access to power in the home state of the target company that oppose the foreign acquisition of that company (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Hypothesis #1

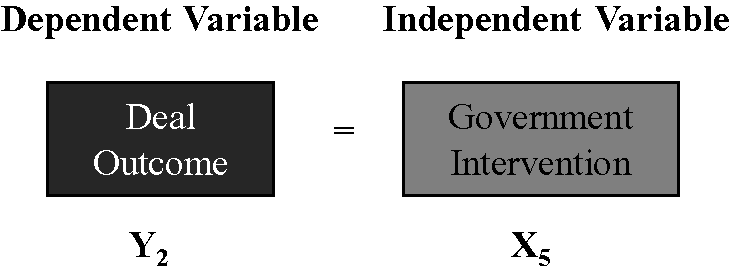

The second hypothesis follows from this, namely: that the outcome of a proposed cross-border merger or acquisition will be strongly affected by the type of intervention employed by state A (Figure 7). In other words, it is expected that unbounded interventions will typically lead to a “no deal” outcome, i.e., where the proposed takeover is blocked or thwarted. Bounded intervention will be expected to result in a deal that is changed or altered to the target state's advantage, and occasionally to lead to a “no deal” outcome. No intervention on the part of the target state's government, on the other hand, will typically mean that a deal will be more likely to go through unmitigated.

Figure 7 Hypothesis #2

The third is a supporting hypothesis. Controlling for the presence of economic nationalism, geopolitical competition between states A and B, competition concerns, and interest group pressure, it is argued that a foreign takeover will be least likely to face visible intervention by state A when any of the following conditions are met: the presence of an institutional investor, the ability to achieve a desired exit, fear of a less-friendly bidder, the national security concerns have been previously addressed, the deal is advantageous for another reason, or internal intervention is pursued (Figure 8). While resource and space constraints prevent a full statistical testing of this hypothesis, it will be examined qualitatively in Chapter 6 (which discusses those cases where governments do not intervene in foreign takeovers), and may prove fertile ground as an avenue for future research.

Figure 8 Hypothesis #3

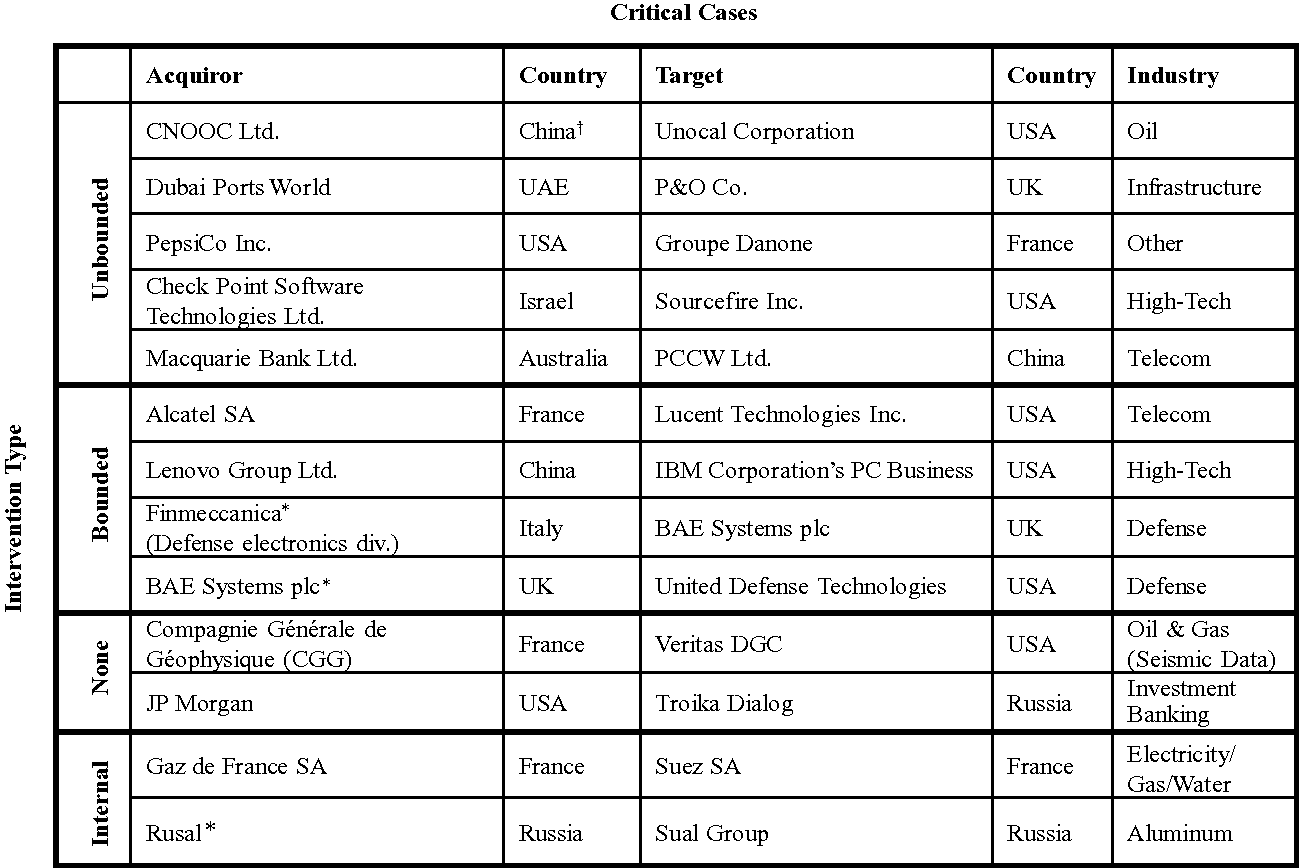

The first and second hypotheses will be rigorously tested, both quantitatively and qualitatively. They will be looked at qualitatively through an examination of ten critical cases and three illustrative supporting cases across all four categories of: (1) unbounded intervention, (2) bounded intervention, (3) no intervention, and (4) internal intervention. These cases are listed in Figure 9.

Figure 9 Critical cases

† The company is listed in Hong Kong.

* Abbreviated case included for illustrative purposes.

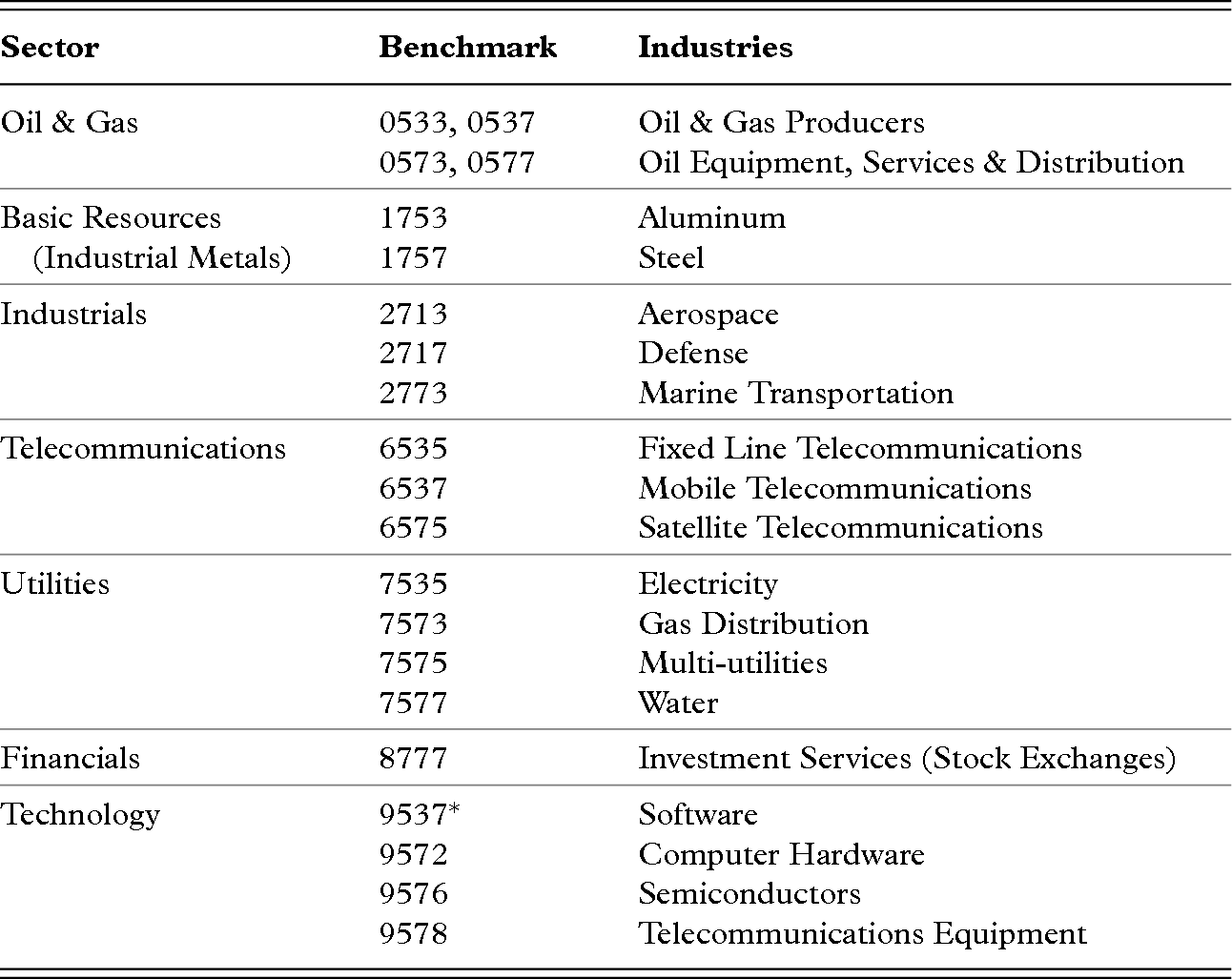

The data will also be examined quantitatively through the use of categorical data analysis (CDA). Toward this end, a database was created of every cross-border M&A transaction in a set of sectors that states commonly associate with national security (Figure 10), which occurred in the six years following 9/11. There are a few reasons for adopting these parameters. First, the start date of the database was chosen because the security environment changed on September 11, 2001 in a manner sufficient to cause some states to be concerned with sectors of the economy that had previously not been identified with national security. The US, for example, now includes the “critical infrastructure” of the nation among such sectors. As the US is subject to the most foreign takeovers of any one country on a yearly basis (UNCTAD 2016b), it is important to limit the time frame in such a way that the cases can be considered comparable. The database ends in 2007, just before the beginning of the Great Recession, which had an immediate, negative, and severe impact on cross-border mergers and acquisitions activity globally.42 The time period of the database thus offers a relatively stable economic and security environment in which to test our hypotheses, though both of these environmental factors vary sufficiently during this period for the purposes of quantitative analysis.

| Sector | Benchmark | Industries |

|---|---|---|

| Oil & Gas | 0533, 0537 0573, 0577 | Oil & Gas Producers Oil Equipment, Services & Distribution |

| Basic Resources (Industrial Metals) | 1753 1757 | Aluminum Steel |

| Industrials | 2713 2717 2773 | Aerospace Defense Marine Transportation |

| Telecommunications | 6535 6537 6575 | Fixed Line Telecommunications Mobile Telecommunications Satellite Telecommunications |

| Utilities | 7535 7573 7575 7577 | Electricity Gas Distribution Multi-utilities Water |

| Financials | 8777 | Investment Services (Stock Exchanges) |

| Technology | 9537* 9572 9576 9578 | Software Computer Hardware Semiconductors Telecommunications Equipment |

* Included only when the target company is known to retain a defense-related contract at the time of the transaction.

Note: Sector, benchmark, and industry titles sourced from www.icbenchmark.com.

Figure 10 Commonly identified national security sectors (listed by ICB code)

Second, it is maintained here that the sectors listed in Figure 10 are those that are most often identified by nations with national security in the post-9/11 environment. As most states prefer to maintain a flexible approach to the scope of security, few choose to actually define or delineate those sectors they associate with national security, as already discussed. The economic sectors identified with national security have thus changed over time (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006).43 This list, therefore, does not attempt to be exhaustive, but seeks to represent those basic industries that both anonymous and written sources most commonly identify as posing security concerns vis-à-vis foreign takeovers today (see e.g., Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006; UNCTAD 2016b; Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016). Some sectors have been purposely left out because of the lack of identifiable (versus actual) intervention activity in recent years, making it difficult to accurately assess levels of government interference. Figure 10 identifies each sector used in this study according to its “Industry Classification Benchmark” (ICB; a coding system used to track M&A transactions).44 Given the thousands of cross-border M&A transactions that took place globally during this time period, it was important for practical reasons to narrow the statistical inquiry down to those sectors where we are most likely to see intervention. The only case that arose in the course of my research that falls outside of these sectors for the time period of this database, the PepsiCo/Danone case, has been included in the critical case studies. The dynamics and findings should not change, however, if the hypotheses were to be tested against all sectors of the economy.

The cases are limited in scope to mid- to large-cap deals where the enterprise value of the target company is estimated to be over $500 million. This is largely because small-cap deals often do not receive the type of global press, analyst, sector, and database coverage necessary to ensure accurate coding of all of the variables involved in the creation of the database. Coverage for mid- to large-cap deals, however, is extremely good, allowing for comprehensive and accurate coding of these transactions.

Cases are also limited to those in which companies in the US, China, Russia, or one of the first fifteen members of the EU were the targets. This set of countries has been chosen for a number of reasons. First, and most importantly, they offer a wide range of approaches to government intervention in foreign takeovers. Second, they offer variance in that some of the first set are “advanced industrialized” societies, while China and Russia may be considered to be advanced industrializing powers. The inclusion of the latter is important to demonstrate that these hypotheses do not only hold for the most advanced Western industrial nations. At the same time, it does not make sense to include lesser developed nations among the cases examined here, because the developing world is subject to a separate set of dynamics within the process of globalization and interdependence that would make those cases less comparable. The advanced Western industrial states of Australia and Canada were not included in the dataset because their respective “national interest” and “net benefit” tests for FDI can make it difficult to disentangle when these states intervene on the grounds of national security from when they do so for more traditional economic protectionist reasons (e.g., to save jobs), making cases involving these countries less comparable.

Third, both the US and the EU belong to strong security communities, from within which foreign takeover bids are likely to originate. Furthermore, this activity flows in two directions within those security communities. US companies will take over EU companies, and vice versa, in the transatlantic security community. Within the community of the EU itself, foreign takeovers also occur without unidirectional flow. Russia and China provide an excellent contrast to this. Even though Russia may arguably maintain a series of strong alliances that resembles a security community, the nations within that community rarely engage in takeovers of Russian companies, but Russian companies will often seek acquisitions within its allied nations as well as without. The same is largely true for China.

Finally, it is important to include non-US states in the database because the theory of non-military internal balancing presented in this work is neither US-centric nor necessarily dependent on a unipolar environment. Cases involving the US do figure prominently in this study, as the US remains a hegemonic power, is the recipient of more cross-border M&A than any other country alone, accounts for roughly one-fifth of the value of cross-border M&A globally as a recipient target country (though this of course varies by year),45 and has a highly institutionalized and sophisticated approach to addressing national security risks in the context of FDI. Yet, because the theory presented in this work is not US-centric or dependent upon a specific power context (uni-, bi-, or multipolar), it is also very important to examine not just those cases in which the US is being balanced against, but also those where the US might be balancing another state, or where balancing might be occurring against other states entirely, such as China, Russia, or France. In all, eighteen target countries are thus examined in the dataset, and five are covered in the critical case studies. Again, it would be an excellent area of further study to include a greater number of countries in the dataset, but this would have exponentially increased the number of cases studied beyond the point of feasibility for this work, without necessarily improving the picture or understanding sought herein.

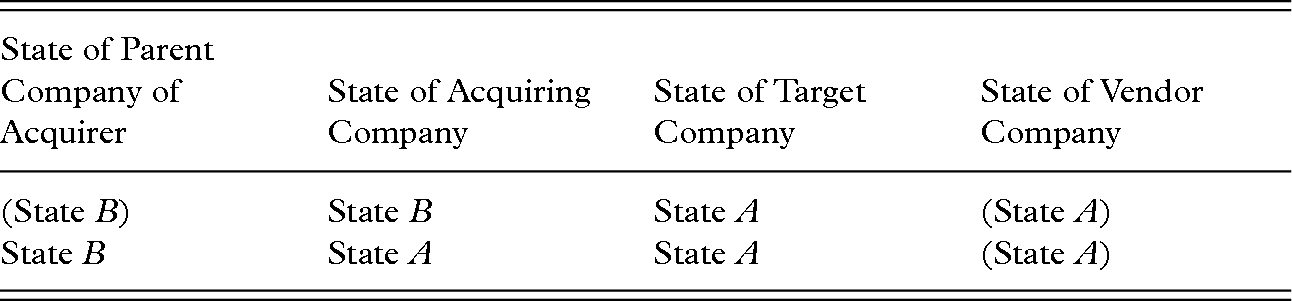

For the purposes of this investigation, the parameter of cases was also narrowed to those examples of the purest form of cross-border M&A in order to allow for the clearest possible investigation of the relationship between the host state of the target company (state A) and the host state of the acquiring company (state B). In other words, cross-border cases were limited to those that took one of the forms represented in Figure 11.46 In all, 209 cases were determined to fit these criteria, out of the 1,238 M&As that fit the other parameters of the database outlined earlier.

| State of Parent Company of Acquirer | State of Acquiring Company | State of Target Company | State of Vendor Company |

|---|---|---|---|

| (State B) | State B | State A | (State A) |

| State B | State A | State A | (State A) |

Note: Certain values of the vendor and parent companies have been placed in parentheses to signify the fact that they may or may not necessarily be present in a given transaction.

Figure 11 Cross-border case types47

Conclusion