Each morning before sunrise an army of traders arrive at their desks, switch on their screens, and start fielding calls. On most days, the flow of trades that pass through their hands represents the normal activity of an ever-deepening, globally interdependent financial market. These traders coordinate a complicated international marketplace, where orders usually come from institutional investors motivated solely by the maximization of profit.

Yet, some days are different, and on those occasions this army of civilians may receive calls motivated not by profit, but by a different calculus entirely: a calculus based on a long-term understanding of the power of states, and of how that power is achieved, managed, and balanced over time. When that happens, these traders in front of their Bloomberg terminals seem more like frontline soldiers manning the radars, as a battle for national power – where the economy of the nation is understood to be paramount to its future fortunes – is played out through them.

Such battles on the open market do happen. One only need talk to the traders who witnessed the dawn raid on Rio Tinto's stock in 2008 to understand this. At that time, the Australian mining company BHP Billiton was planning to acquire Rio Tinto, a miner and producer of iron ore, aluminum, copper, and other metals that was listed on both the Sydney and the London stock exchanges. China, already the largest importer of iron ore, showed concern that the combination of Rio and BHP would lead to a near monopoly over the seaborne iron ore imports vital to its growing and industrializing economy, potentially exposing it to price manipulation and/or future reductions in supply.1 A combined Rio and BHP would have accounted for around 40% of the iron ore exported globally, and the bulk of both companies’ seaborne iron ore traveled from their mines in Australia to China and East Asia. Just one other company, Brazil's Vale, held an additional 30% of the market share at the time. Thus, while China was not the only country showing concern over the potential anti-competitive implications of the tie-up,2 it was likely to be the most directly affected buyer of seaborne iron ore. Chinese regulators could review the deal, but because Chinese assets were not being acquired as part of the transaction, a ruling by these regulators would be difficult to enforce without cooperation from the companies involved.

And so, in the early hours of February 1, 2008, the Chinese government-owned Aluminum Corporation of China (Chinalco), in conjunction with the US aluminum company Alcoa, began purchasing stock of Rio Tinto on the open market in a widely acknowledged effort to block its planned takeover by BHP Billiton. Together, they took an overall stake in Rio Tinto of 9% for $14 billion, paying a premium of 21% over Rio's stock price, and making a potential takeover by BHP more difficult (Bream Reference Bream2008; Bream & Smith Reference Bream2008). No formal statement or diplomatic action was necessary – China accomplished its goal through a quick, targeted financial transaction on the open market. The dawn raid not only halted BHP's attempt to fully acquire Rio, it also signaled China's willingness to protect its interests by preventing the acquisition of one company by another company on the global stage.

The market is in many ways the next frontier of strategic interaction for states. When national security is involved, strategic interactions involving cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A) can have deep parallels to more traditional inter-state balance-of-power dynamics, yet they are rarely discussed within the context of international relations theory. This book uncovers these parallels and the insights they provide. It examines when, how, and why states intervene in the cross-border M&A of companies to balance against other states in the international system.

International Finance and International Security

For decades, the M&A of companies across national borders has acted as a key driver of globalization. This fundamental role within globalization remains the same, despite a natural rise and fall in the number of deals that occur during economic booms and contractions. The general trend among nations has been toward “investment liberalization” (UNCTAD 2016b, 90), and, in many sectors of the economy, from service to consumer goods, cross-border M&A activity now occurs with few impediments beyond those that domestic M&A deals normally face. In other sectors, long identified by states as vital to their national security – such as aerospace and defense, energy, basic resources, and high technology – acquisitions by foreign companies may face greater scrutiny. This is because all states maintain the sovereign right to veto attempts by foreign entities to acquire domestically based companies (in these or any other sector of the economy), when they believe the transaction in question poses a risk to national security.

While the resort to formal vetoes of the foreign takeovers of companies is relatively rare,3 the employment of other means to block or prevent such transactions is not. Indeed, the threat (and use) of domestic barriers to block foreign acquisitions on national security grounds is an increasingly typical phenomenon with which global economic actors must contend.4 There have been numerous examples in recent years of such barriers being implemented or encouraged at the state level. These have ranged from government actions taken to block or modify specific transactions, to the introduction or fine-tuning of wider legal and regulatory measures designed to generally improve the state's ability to address the national security issues raised by some cross-border M&A – though it should be noted that the latter move toward greater regulation has often been spurred by the state's actions in relation to specific transactions and the national debate surrounding these actions.

Some of the most well-known examples of government intervention into cross-border M&A on national security grounds include when the US House of Representatives passed legislation instrumental in getting the China National Offshore Oil Corporation's subsidiary CNOOC to withdraw its bid for the American-based Unocal Corporation in 2005, and when it passed legislation forcing Dubai Ports World (DPW) to divest the US ports involved in its acquisition of the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) in 2006. In both cases, Congress cited concerns over the deals’ security implications. Other well-known examples include the 2005 French government decree specifying eleven different strategic sectors it considers vital to national security, making M&A in those industries subject to prior authorization by its Ministry of the Economy. This was largely in response to an unwanted attempt by the American company Pepsi to take over Danone, a French national champion (see Chapter 3). France widened the scope of its list of strategic sectors again in 2014, in order to ensure government approval would be needed before General Electric, another American company, could acquire Alstom, a French conglomerate involved in industries from high-speed trains to nuclear power (see Carnegy et al. Reference Carnegy, Stothard and Rigby2014; Shumpeter 2014). France even created a sovereign wealth fund (SWF) in 2008, the Fond Stratégique d'Investissement, to help protect its strategic companies from foreign acquisition. Similarly, the Italian government issued a decree in 2011 protecting Italian companies in strategic sectors from foreign acquisition, and also created a state investment fund (the Fondo Strategico Italiano, subsequently renamed CDP Equity) to bolster Italian companies in eight designated strategic sectors and to decrease their likelihood of becoming foreign takeover targets. For years, the German government even encouraged a “German solution” to prevent one of its companies, Volkswagen (VW), from becoming the target of a foreign acquirer – fighting a protracted battle with the European Commission over the 1960 “VW Law,” which helped protect it from foreign takeover (Barker Reference Barker2011; Bodini Reference Bodini2013; Harrison Reference Harrison2005).5

Even in the best of economic times, it must be asked whether such government intervention poses a threat to economic globalization, and, more fundamentally, how it is compatible with the liberal economic order on which international security largely rests. The importance of such questions looms even larger in the context of an international economy that is still recovering from the severe dislocation of the global financial crisis, which naturally slowed the level of cross-border M&A activity, and that is just beginning to address other unprecedented events, such as Britain's 2016 decision to leave the European Union (EU).

Puzzling Behavior

Since Bretton Woods, Western leaders have sought to establish an international order founded on economic liberalism and free trade in the hope that increased economic interdependence will decrease the likelihood of future wars and improve the global standard of living. Hence, many see it as odd that the types of domestic barriers to cross-border M&A being discussed here are implemented or encouraged at the state level. Stranger still is that these domestic barriers are often employed against the wishes of corporate shareholders and the advice of economists. Traditional interest group and domestic politics explanations, therefore, cannot account for this behavior, because states often intervene against the parochial interests of companies and other domestic groups on behalf of national security. Thus, the very states that helped found the liberal economic order are taking actions that do not always make rational economic sense to the market, shareholders, or economists. In this case, then, there must be another, more pressing rationale behind such behavior.

Given this context, it is a striking puzzle that states are engaging in this type of behavior not only against their strategic and military competitors, but against their allies as well. France, Germany, Italy, and Spain, for example, have all voiced concern about the acquisition of strategic companies by foreign entities hailing from within the EU. For, while the 2004 European Takeover Directive does much to reduce protectionist measures among its member states, and helps to guarantee the free movement of capital promised in the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU, it does not strip member states of their rights under Article 65 of that Treaty “to take measures which are justified on grounds of public policy or public security,” including national security, in relation to the movement of that capital across its borders.6 For example, former French Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin, under President Jacques Chirac, openly supported a policy of “economic patriotism” meant “to defend ‘France and that which is French’ by declaring entire sectors of French industry off-limits to foreigners,” including other Europeans and members of the transatlantic community (Theil Reference Theil2005). As already mentioned, the scope of this policy was widened under President François Hollande's government. In the interim, President Nicolas Sarkozy, though generally considered more market-friendly, also clearly supported policies identified with economic patriotism, as demonstrated by the creation of the Fond Stratégique d'Investissement and his efforts to prevent a number of France's national champions (Aventis, Danone, Alstom, and Société Générale) from being taken over by other European or American companies (see Betts Reference Betts2010; Puljak Reference Puljak2008). This desire to create and protect “national champions” in sensitive sectors is no longer simply a sign of being “French,” however, as other nations within Europe, such as Italy, Spain, and Germany, have also signaled a preference for domestically headquartered white knights to acquire the susceptible takeover targets in their countries (see Financial Times 2005b).7

Why are states that are members of a security community based on economic liberalization and integration willing to engage in this specific form of economic protectionism against one another? The purpose of this book is to solve the riddle of this seemingly contradictory behavior. I argue that the basis for such action may be found in the struggle for economic power among states. While states have largely accepted and adhered to the liberal principle that free trade results in absolute gains beneficial to all states, this particular aspect of inward foreign direct investment (FDI) can have direct consequences for national security and, consequently, remains a last bastion of protectionism even among the most benign liberal states.8

Drawing upon the international relations literature on the balance of power among states, I argue that governmental barriers to cross-border M&A are used as a form of non-military internal balancing. This concept refers to those actions that seek to enhance a state's relative power position vis-à-vis another state through internal means, without severing the greater meta-relationship at stake between them. Unlike soft balancing, non-military internal balancing is classified by both the objectives of state behavior and the type of conduct used to achieve those objectives. The power being balanced is also defined differently from the traditional sense of the term. In a world where nuclear power has lessened the rewards of territorial conquest and made great power hot wars less likely, many advanced industrial and industrializing states have less reason to fear that their territorial sovereignty will be jeopardized (Mandelbaum Reference Mandelbaum1998/99; Mueller Reference Mueller1988). At the same time, the expansion of economic globalization has increased the reasons for states to be concerned that their economic sovereignty will remain intact. As a result, states are now as concerned with the economic component of power as they are with its military component, and will seek to balance both appropriately.

This type of non-military internal balancing will take different forms or guises when it is motivated by different factors. Non-military internal balancing through intervention into cross-border M&A may, for example, be unbounded in nature, meaning that the state takes direct action intended to block a specific transaction. Alternatively, such balancing may be bounded, meaning that the state takes direct action to instead mitigate the negative effects of the deal, while still allowing it to occur in modified form.

The puzzle can then be solved if the use of such domestic barriers to block or mitigate foreign takeovers on national security grounds is understood to be primarily motivated by either pressing geostrategic concerns or economic nationalism.9 In the latter instance, such behavior is evidence of a desire for enhanced national economic power and prestige vis-à-vis other states, friend and foe alike. In the former case, this behavior constitutes a more severe form of non-military internal balancing, which allows states to secure and enhance their relative power for long-term gain, without destroying the greater meta-relationship between the two states in the short run. The exact form that intervention takes, and the motivations behind it, will vary with the nature of the relationship between the countries involved and the exact nature of the threat posed by the transaction in question.

The geostrategic dimensions may also extend beyond industries that are traditionally associated with national security. For example, states may use the terms national security and strategic sector in this context in ways that go beyond the realms, and industries, neorealists and neoliberals might traditionally consider vital to hard power. The French, for instance, originally included the gaming sector on their list of strategic industries, because of its potential connection to money laundering (Buck et al. Reference Buck, Hollinger and Braithwaite2006b), and in the 2010s various groups within the US and China called for the recognition of certain elements of the agricultural sector as essential to critical infrastructure and national security due to concerns over bio- and food security. It may also sometimes seem that states use the types of barriers discussed here selectively, and in a manner that can appear both opaque and inconsistent. Yet, once it is determined why states are willing to engage in such ostensibly protectionist strategies in the most unlikely cases (i.e., within security communities founded on economic integration), one should be better able to predict what companies and sectors they will seek to protect, and when.

Intervention in Empirical Context

The US Example

History is marked by periods of increased government intervention into foreign takeovers on the grounds of national security, and the US provides an excellent example of this phenomenon. Times of heightened security awareness combined with surges in protectionist sentiment – most notably surrounding World War I, World War II, the 1970s, the 1980s, and the post-9/11 period – have corresponded to the implementation of formal government measures to ensure that cross-border M&A does not jeopardize US national security (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006; Kang Reference Kang1997). The 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA) was implemented in response to concerns over German attempts during World War I to conduct espionage and other war-related activities through the takeover of US companies, giving the President new controls and power over US subsidiaries of foreign-owned companies (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006). In 1975, the Committee on Foreign Investments in the United States (CFIUS) was established by Executive Order 11858 in response to mounting concern over a rise in foreign investment from states within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which was feared to be politically motivated in the aftermath of OPEC's 1973–74 oil embargo (see Jackson Reference Jackson2010, Reference Jackson2011b; Kang Reference Kang1997, 302, 311). Executive Order 11858 gave the new interagency committee, chaired by the Secretary of the Treasury, the “responsibility within the Executive Branch for monitoring the impact of foreign investment in the US,…coordinating the implementation of US policy on such investment,” and “review[ing] investments in the US which…might have major implications for US national interests.”10

Fears over high levels of Japanese investment in the 1980s, combined with concern over the potential Japanese acquisition of sensitive US high-technology companies, eventually led to the 1988 Exon-Florio amendment to Section 721 of the Defense Production Act (DPA) of 1950 (Jackson Reference Jackson2010).11 This provision provides the US President with the authority and specific jurisdiction to prohibit foreign takeovers deemed to threaten national security when existing laws beyond the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) cannot provide for its adequate protection. That same year, Executive Order 12661 amended Executive Order 11858 to delegate the President's authority to investigate and review such foreign takeovers to CFIUS. By 1992, the Byrd Amendment to the DPA further stipulated that CFIUS be mandated to investigate proposed takeovers in which the acquirer was “controlled by or acting on behalf of a foreign government.”12

Since the 2000s, the US has seen a new surge in both intervention and related legislation, and intense media coverage and political debate has surrounded the proposed foreign takeovers of a number of US companies. This surge arguably began when, on June 22, 2005, the majority government-owned China National Offshore Oil Corporation's subsidiary CNOOC announced its bid to acquire the California-based Unocal Corporation. Extensive national and congressional debate over the sale of one of the largest US oil and gas companies eventually resulted in legislation that left CNOOC with extensive delays and facing the likelihood of further opposition to the deal, effectively giving it little choice but to withdraw its bid.13 On November 29, 2005, the UAE-based DPW launched its bid for P&O, a British ports operator. Few concerns were raised in Britain, which has close ties with Dubai, and few were expected from the US, an ally of the UAE in the Global War on Terror. Yet the deal, which involved the transfer of five US container ports from P&O to DPW, eventually raised a furor that resulted in a surprising “70% of all Americans…opposed” to the transaction (Frum Reference Frum2006). Faced with the possibility of the deal being blocked, P&O offered to divest the ports in question, and eventually sold them to the American International Group (AIG), allowing them to remain under US control (Wright & Kirchgaessner Reference Wright and Kirchgaessner2006).

Around that time, the Department of Defense (DOD) also raised concerns over the proposed purchase of the US high-tech network security firm Sourcefire by the Israeli company Check Point Software Technologies (Martin Reference Martin2006). Check Point subsequently withdrew its bid while it was being reviewed by CFIUS, only “a week before a federal…report which insiders say would have blocked the merger on the grounds of national-security interests” (Lemos Reference Lemos2006). In 2006, CFIUS also undertook a retroactive review of a 2005 takeover involving the purchase of a US voting machines firm, Sequoia Voting Systems, by a Venezuelan software company, Smartmatic, due to fears that the company might have ties to the Venezuelan government of Hugo Chávez (Golden Reference Golden2006). By November 2007, Smartmatic had announced it had sold Sequoia to its American management, in order to avoid having to undergo a full investigation by CFIUS (O'Shaughnessy 2007; Smartmatic 2007).

This surge in concern over such takeovers eventually led to the passage of the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA), which aimed to clarify the foreign acquisition review process in the US and strengthen its protection of national security. Following FINSA, a number of other deals were blocked or mitigated on national security grounds, though only three resulted in a formal presidential veto. For example, in December 2009, the Chinese company Northwest Nonferrous withdrew its bid for a majority stake in the US mining company FirstGold after CFIUS informed both parties it would recommend the President block the deal, which raised “serious, specific, and consequential national security issues,” including the proximity of FirstGold properties “to the Fallon Naval Air Base and related facilities” (Legal Memorandum 2009; Reuters 2009). The US government was also reportedly concerned that the deal would give China access to the particularly dense metal tungsten, which is used in making missiles (Kirchgaessner Reference Kirchgaessner2010). The Chinese company Tangshan Caofeidian Investment Corporation (TCIC) withdrew its planned majority stake in the US solar power and telecommunications company Emcore in June 2010, “in the face of national security-based objections” raised by CFIUS, which may have been related to Emcore's position as “a leading developer and manufacturer of fiber-optic systems and components for commercial and military use” (Keeler Reference Keeler2010). The takeover of the US company Sprint by Japan's Softbank was allowed in 2013, but was mitigated (i.e., modified) by CFIUS on national security grounds, as Sprint provides telecommunications services to the US government. Concern was expressed that Softbank might, in the future, use the Chinese firm Huawei – branded the previous year by Congress’ Permanent Select Intelligence Committee as “a threat to US national security” – as a supplier of network components; a concern which arose in part because Clearwire, a company Sprint itself was in the process of buying, already used equipment supplied by Huawei (Kirchgaessner & Taylor Reference Kirchgaessner and Taylor2013; US Congress House 2012). Modifications to the deal therefore included giving the US government veto power over the combined entity's future suppliers of network equipment (Taylor Reference Taylor2013).14 It should be noted that CFIUS also successfully mitigated or blocked the foreign takeovers of a number of foreign-headquartered companies on national security grounds.15

In addition, since FINSA, the US has conducted several retroactive reviews of investments that were not voluntarily filed with CFIUS prior to their completion. In February 2011, CFIUS effectively forced Huawei to divest the computing technology assets it acquired from 3Leaf Systems in May 2010 (see Jackson Reference Jackson2016a; Raice & Dowell Reference Raice and Dowell2011). In June 2013, Procon Mining and Tunneling, which is affiliated with the Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE) Sinomach, announced it would divest its investment in Canada's Lincoln Mining following a CFIUS review that allegedly raised national security concerns over “the proximity of Lincoln's properties to US military bases” (Pickard et al. Reference Pickard, Daly and Neelakantan2013). In 2013, CFIUS also ordered the divestment of the Indian company Polaris’ majority stake in the US firm Identrust, which provided cybersecurity services to banks and the US government (Matheny Reference Matheny2013). Each of these companies voluntarily complied with CFIUS’ recommendations before it became necessary to force a presidential decision on them. This was not the case, however, when one company's refusal to comply with a CFIUS divestment order resulted in the second formal presidential veto of a foreign investment in US history, and the first veto to be made in twenty-two years. On September 28, 2012, Barack Obama issued a Presidential Order for Ralls, a company owned by two Chinese nationals, to divest its four wind farm sites – located in close proximity to restricted air space in Oregon used for testing drones – to an approved purchaser on the grounds of the national security concerns raised by the deal (see Crooks Reference Crooks2012; Obama Reference Obama2012).16

In December 2016, President Obama also formally vetoed the acquisition of the US business of a German semiconductor company, Aixtron, by an ultimately Chinese-owned fund, Grand Chip Investment, on national security grounds (see Obama Reference Obama2016). According to a press statement by the US Treasury Department, Grand Chip's owners had financing from a company owned by the China IC Industry Investment Fund, which is a “Chinese government-supported…fund established to promote the development of China's integrated circuit industry” (US DOT 2016b). The same press release disclosed that the national security concern flagged in the deal “relates, among other things, to the military applications of the overall body of knowledge and experience of Aixtron” in the area of semiconductors (US DOT 2016b). Notably, Germany had already pulled its initial approval of Grand Chip's purchase of Aixtron in October 2016, and was re-reviewing the deal at the time of the US veto because of the security risk it was believed to pose (see Chazan & Wagstyl Reference Chazan and Wagstyl2016).

Less than a year later, President Donald Trump formally vetoed the acquisition of the US company Lattice Semiconductor by Canyon Bridge, an acquisition company whose primary investor was the China Venture Capital Fund (CVCF). The deal had been announced in early November 2016, and it quickly emerged that CVCF was ultimately owned and funded by a Chinese SOE (China Reform Holdings) linked to China's State Council and intended to “invest in strategic emerging industries related to national security” (Baker, Qing, & Zhu Reference Baker, Qing and Zhu2016). By early December 2016, just days after President Obama vetoed the Aixtron deal in the same industry, twenty-two US congressmen wrote to the Chair of CFIUS arguing that the acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor should be blocked on national security grounds, including the potential threat it posed to the “US military supply chain” (Roumeliotis Reference Roumeliotis2016). After three separate filings with CFIUS, President Trump vetoed the deal in September 2017 over national security concerns that both the President and CFIUS believed “cannot be resolved through mitigation,” including the integrity of the “semiconductor supply chain…and the use of Lattice products by the US government,” as well as “the potential transfer of intellectual property to the foreign acquirer [and] the Chinese government's role in supporting” the deal (US DOT 2017; see also Trump Reference Trump2017).

Intervention Worldwide

This phenomenon is not limited to the United States. Government interventions into M&A activities that result in effectively blocking or changing deals between multinational corporations are not uncommon.17 While states have long reserved the sovereign right to intervene in foreign takeovers on national security grounds, and a number of states already had mechanisms for screening such investments, the surge of intervention that began in the 2000s was accompanied by a related wave of national legislation updating these mechanisms, or setting up formal regulatory procedures to replace processes that may have been less transparent or more ad hoc in nature (see UNCTAD 2016b, 93–100).

The spate of government intervention into cross-border M&A activity within the EU raised concern that there had been a rise in economic nationalism in the region; a concern that remains strong in the wake of the Euro crisis and the UK's decision to leave the EU.18 As already discussed, much of this interventionism has surprisingly also been aimed at foreign takeovers originating from within the EU's own security communities. The Spanish government, for example, blocked the attempted takeover of the Spanish energy company Endesa by the German company E.ON in 2006, in defiance of the European Commission, resulting in three separate rulings by the Commission and a ruling by the European Court of Justice in 2008.19 The initial efforts of a number of European governments to block the takeover of the French steel company Arcelor by the Dutch-based steel company Mittal in 2006, on the perceived basis that it was run by an individual of Indian origin (even though he was a British resident), further serves to highlight the capability of governments to see even military allies as economic foes. The rumored acquisition of the UK's BAE Systems by the Dutch-registered EADS in 2012, which would have required approval from their UK and their French and German government shareholders respectively, as well as from the US authorities, collapsed after little more than a month of discussions over the inability to find common ground on a variety of security and other concerns.

Hungary passed a law in 2007 designed to protect those companies it believes are strategically important from foreign takeover. Intended to defend the Hungarian oil and gas company MOL from a takeover bid by Austria's OMV, it came to be known as the “Lex MOL.” The law had to be modified in 2008 after the European Commission informed the Hungarian government that some of its provisions went beyond European law (see FT 2009; Platts 2008). In 2015, Poland adopted the Act on the Control of Certain Investments, creating a mechanism for screening foreign investments of more than 20% in companies in strategic sectors like energy, telecommunications, and defense, which gave the Polish Minister of the State Treasury the ability to block such investments on the grounds of “security and public governance” (Krupa Reference Krupa2015; UNCTAD 2016b, 93).

The German government added a mechanism for screening foreign investment stakes of over 25% hailing from non-EU and European Free Trade Association states for national security risks in 2004, initially in specific industries around weapons and cryptography, though the scope was broadened to include enterprises involved in tanks and tracked vehicle engines in 2005 (US DOS 2014b, 3). By 2009, after widespread public debate over the effect of foreign SWF investments in the country, the national security review process was expanded “to apply to a German company of any size or sector in cases where a threat to national security or public order is perceived” (US DOS 2014b, 3). Despite the wording of its regulatory regime, however, the German government has also shown concern over investments hailing from within the EU itself. Citing national security concerns over the sensitive technology involved, it decided in 2008 that it was better to buy back its national printing press, the Bundesdruckerei, rather than see it auctioned to foreign bidders such as France's Sagem or the Netherlands’ Gemalto, when it seemed that no German company would try to win the auction.20

Similarly, tensions arose between Italy and France in 2011, when a series of large Italian companies (including Bulgari and Parmalat) were taken over by French ones and Italy's Finance Minister Giulio Tremonti sought to stem the tide by trying to prevent Edison, an Italian power company, from being taken over by the French group EDF.21 In 2012, Italy established a formal mechanism for screening foreign takeovers of companies engaging in strategic activities (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 58). Under this mechanism, investments in the transport, energy, and communications industries are assessed for their threat to the wider concept of national interest, and such reviews are only applied to foreign investors hailing from outside the EU and European Economic Area (EEA). However, investments in companies engaged in defense and national security are assessed on the basis of their threat to the “essential interests of the state” (i.e., national security), and that review applies to all foreign investors, including those from within the EU (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 58). The Italian government did later allow the takeover of the Italian aerospace manufacturing company Piaggio Aero by the UAE's Mubadala Development Co., as well as the takeover of the Italian aerospace technology firm Avio SpA by the US’ General Electric in 2013, “but subjected both transactions to strict conditions, such as compliance with requirements imposed by the Government on the security of supply, information and technology transfer” (UNCTAD 2016b, 97). Interestingly, Finland replaced its previous screening mechanism with a dual review system similar to Italy's in 2014, and it now looks at all foreign investors – including those from the EU – when assessing cross-border M&A in the defense sector (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 52–3).

Other governments actively seeking to block hostile foreign takeovers on national security grounds include Australia, Canada, China, Japan, and Russia, to name but a few.22 In China, reports were already emerging in 2006 that “acquisitions of Chinese enterprises by foreign companies are increasingly being challenged amidst a growing mood of ‘economic patriotism’” (Yan Reference Yan2006). The Chinese government, for example, blocked the Australian bank Macquarie's bid for its biggest phone company, PCCW, and “stalled” the American-based Carlyle Group's bid for Xugong, the country's biggest maker of construction equipment (Bloomberg 2006; Yan Reference Yan2006). It is also widely held that economic nationalism played a role in the Chinese government's 2008 refusal to allow Coca Cola to buy the Huiyuan Juice company, an attitude many analysts believe remains prevalent in China (see e.g., Browne & Dean Reference Browne and Dean2010; Harmsen Reference Harmsen2009). Additionally, China adopted a number of new laws and regulations in 2007/08, 2011, 2015, and 2016, updating and formalizing some of its mechanisms for screening foreign takeovers (see Chapter 5). Together, these rules prohibit foreign investment in particular industries, and set up a “mandatory national security review system for foreign acquisitions of target military…enterprises” and for businesses in a number of strategic sectors related to national security, such as energy and infrastructure (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 50).

Russia also updated its foreign takeover laws in 2008, identifying forty-two strategic industries where investment may be reviewed for national security risks, approval is required for acquisitions of stakes larger than 25%, and majority stakes require a special permit from a review committee led by the Russian Prime Minister.23 As discussed further in Chapter 5, the scope of this national security review was widened in 2014 to include activities related to infrastructure and transport. In 2013, Russia blocked the proposed takeover of Petrovax Pharm, one of its vaccine producers, by the US company Abbot Laboratories on national security grounds (UNCTADb 2016, 96, 99).

In Japan, Article 27 of the 1949 Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act gives the Minister of Finance the power to prohibit foreign investment when it is determined that “national security is impaired, the maintenance of public order is disturbed, or the protection of public safety is hindered.”24 Though Japanese FDI laws are generally relaxing, concerns have emerged within that country that foreign acquisitions by “developing countries could [threaten] Japan's strategic interests,” causing its Trade Ministry in 2006, for example, to encourage Japanese “steelmakers to adopt poison pills to protect themselves from foreign takeovers” (Economist 2006a). In 2007, the regulatory regime was amended to widen the number of sectors in which investors must notify the Minister of Finance in advance of a transaction, in order to “prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and damage to…defence production and technology infrastructure” (UNCTAD 2016b, 96). Notably, Japan blocked the UK's TCI fund from increasing its minority stake in the Japanese electricity company J-Power on national security grounds, as it felt the group might be able to “affect the planning, operation and maintenance of key facilities such as power transmission lines and implementation of Japan's nuclear power generation” (Terada Reference Terada2008).

Australia and Canada have also strengthened their foreign investment laws, following periods of national debate over the desirability of foreign investment. Yet, while both countries undertake national security reviews of proposed foreign acquisitions, these are carried out alongside (or as part of) larger net benefit and national interest tests that include broader considerations like the effect of a specified transaction on competition, the economy as a whole, and national culture or community.

Under the 1985 Investment Canada Act, for example, Canada may review sizeable foreign investments on the basis of their “net benefit” to society, which in both theory and practice can be used to block transactions that raise national security concerns. The first time Canada blocked a foreign takeover on net benefit grounds was over security concerns, when in 2008 it refused to allow the US company Alliant Techsystems to acquire the Canadian company MacDonald Detweiller (MDA), which held sensitive satellite technology as part of its Radarsat program (Lexology 2016; Simon Reference Simon2008, Reference Simon2009). Canada adopted a formal mechanism to review the national security implications of foreign investments a year later. By March 2016, it reported that these national security reviews led it to block three foreign acquisitions, retroactively order two divestments by foreign investors, and mitigate two deals (ISED 2016, 10). In one case, an investment was also “abandoned” by the acquirer before it could be blocked (ISED 2016, 10). Deals blocked on national security grounds include the attempted purchase of Manitoba Telecom Services’ Allstream division by the Egyptian company Accelero Capital Holdings in 2013, because Allstream ran “a national fibre optic network that provides critical telecommunications services to businesses and governments, including the Government of Canada” (Moore Reference Moore2013). An investment by the Chinese SOE Beida Jade Bird, which would have installed a facility for manufacturing fire alarms in close proximity to the Canadian Space Agency, was also blocked for security reasons (Lexology 2016). In November 2010, however, Canada famously blocked BHP Billiton's bid for PotashCorp on the grounds that it would not be of “net benefit” to Canada, without citing national security concerns (see Simon et al. Reference Simon, Thomas and MacNamara2010).

Australia's Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act of 1975 establishes a screening process for foreign purchases over certain thresholds and under certain conditions. The Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) makes these assessments, and the Treasurer of Australia then has the power to block foreign acquisitions that are not found to be in the national interest, including deals that pose a risk to national security.25 The Act was amended in 2015 to, among other things, lower some thresholds for review and give the FIRB and Treasurer new powers.26 Yet, while Australia has formally blocked deals only a handful of times, it has not always been clear about whether the “national interest” being contravened involves national security or not. For instance, the Treasurer blocked a 2001 bid by the European-based Royal Dutch Shell to become a majority owner in the Australian oil company Woodside on the basis that it would be “contrary to the national interest” to allow Woodside to relinquish its control over the joint-venture project it had with Shell to develop Australia's North West Shelf natural gas resource (Australian Treasurer 2001). In April 2011, Australia rejected an attempt by Singapore's stock exchange, SGX, to acquire the Australian Securities Exchange, ASX, arguing the deal was not in the “national interest” given the “critically important” nature of the business to Australia's economy (Smith Reference Smith2011). In 2013, Australia also rejected the proposed purchase of the Australian agribusiness Graincorp by the American company Archer Daniel Midland (ADM), both because of its importance to Australia's economy (it held 85% of the market) and because “allowing it to proceed could risk undermining public support for the foreign investment regime and ongoing foreign investment more generally” (Australian Treasurer 2013). The Australian government did, however, explicitly cite national security concerns in 2015 when it blocked the purchase of the Kidman & Company land portfolio from all foreign bidders, which were rumored to include both Canadian and Chinese investors, because Kidman is “one of the largest private land owner[s]” in Australia, and 50% of one of its cattle stations (Anna Creek) “is located in the Woomera Prohibited Area,” used for weapons testing (Australian Treasurer 2015; Thomas & Lilly Reference Thomas and Lilly2016).27

Placing the Theory behind Intervention in Context

A Global Perspective and Parsimonious Theory

Though all of this serves to illustrate that strategic intervention into cross-border M&A is not confined to a particular geography, scholarly explanations of these events are mostly limited in context to government intervention by the US.28 Such inquiries provide a depth of valuable insight into how the US operates vis-à-vis foreign takeovers. They also provide invaluable comparisons to the antagonism surrounding takeovers of American companies by the Japanese in the 1980s and early 1990s (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006; Kang Reference Kang1997). These inquiries do not, however, test their assumptions across different states, or seek to create a generalizable theory that can explain when and why states intervene in M&A activity on national security grounds. While I do not disagree that states evaluate all foreign takeovers on a case-by-case basis according to their own internal national security criteria, there do seem to be some general tendencies among states concerning when and why they engage in this behavior. These may in turn be used to create parsimonious theory. Moreover, by not adopting a more global scope of inquiry, many theorists fail to examine some of the truly puzzling aspects of state behavior regarding foreign takeovers that are discussed in the following chapters. With that in mind, this book will seek to build on and draw from the work of these scholars, the public policy world, financial research, interviews, and empirical data to create a generalizable and probabilistic theory of when and why the governments of advanced industrial and industrializing societies intervene in foreign takeovers on national security grounds.

Foreign Direct Investment: Why Focus on Foreign Takeovers Alone?

Though states interact strategically over other forms of FDI, this book focuses specifically on cross-border M&A in order to fully understand its unique dynamics and implications for how states balance power in the economic sphere. As defined by Graham and Krugman, FDI involves the “ownership of assets in one country by residents of another for purposes of controlling the use of those assets” (Graham & Krugman Reference Graham and Krugman1995, 8). FDI primarily consists of cross-border M&A and new greenfield investment, but may also include financial restructuring and the extension of capital for the purpose of expanding existing business operations (OECD 2008, 203).29In technical terms, cross-border M&A entails “the partial or full takeover or the merging of capital assets and liabilities of existing enterprises in a country by [enterprises] from other countries,” and greenfield investment refers to the “establishment of new production facilities such as offices, buildings, plants, and factories, as well as the movement of intangible capital (mainly in services)” (Gilpin Reference Gilpin2001, 278; OECD 2008, 87; UNCTAD 2006, 1, 15). More simply put, cross-border M&A involves the purchase or sale of existing assets or equity, while greenfield investment establishes new assets.

These alternative modes of market entry often have different implications and raise different concerns for the countries involved. For the state and society in which the target company of a cross-border merger or acquisition is located, there is a great deal of uncertainty that attends the transaction process. Existing operations may face “expansion…or reduction” (UNCTAD 2006, 15), jobs may be lost, domestic workers may be replaced with foreign nationals, cutting-edge technology may go to another country that is viewed as a competitor, or control over domestic resources might be lost. On the other hand, greenfield investment “directly adds to production capacity” and “contributes to capital formation and employment generation in the host country” (UNCTAD 2006, 15). Foreign takeovers might also lead to the same good fortune, but it remains difficult for the host country to forecast such outcomes in advance, and, as will be shown, this can contribute to greater uncertainty surrounding M&A and a resulting focus on relative advantages as states interact within the international financial environment.

Cross-border M&A and greenfield foreign investments are thus often governed by (and subject to) different legal and regulatory frameworks in the target state, because of the varying implications for the economies receiving them. In other words, companies face different rules governing market entry, depending on the type of FDI they pursue. In the US, for example, the CFIUS process described earlier does not apply to greenfield investments, which traditionally have not been viewed as posing the same type of national security risk as the takeover of an existing entity. Often, the regulatory regimes covering foreign takeovers of companies, which provide for formal government reviews of the effect of a particular transaction on competition and national security, are specific to that particular type of FDI, and foreign investment restrictions on national security grounds “do not generally [apply] to new establishments” (Jackson Reference Jackson2013, 6). Where countries do not have separate regimes for screening different types of FDI, they may still have different thresholds for triggering reviews of these different modes of investment.30 Moreover, most interventions into FDI discussed here have been focused on cross-border M&A, while instances of concern over greenfield FDI on national security grounds have been less widespread. This inquiry thus focuses specifically on cross-border M&A, rather than all forms of FDI including greenfield investments, in order to maintain the best possible comparison across countries of the type of behavior under investigation; though the latter would be an interesting area for further study.

Cross-Border M&A, Economic Interdependence, and Globalization

Any theory examining the relationship between the state, foreign takeovers, and the balance of power must also recognize the role that cross-border M&A plays within the global economy and the international system as a whole. As discussed in the next chapter, when an individual cross-border merger or acquisition is completed successfully, it can create certain economic dependencies between the states involved in the transaction. Some states will seek to take advantage of these dependencies, triggering the balance of power dynamics examined in this book. At the same time, however, cross-border M&A activity as a whole is part of the broader process of the deepening of economic interdependence among states within the international system, and of “the growing integration of economies and societies around the world” referred to as “globalization” (World Bank 2009, emphasis added).31 There is thus an integral connection between foreign takeovers, economic interdependence, and globalization.

The role of foreign takeovers as a driver of economic globalization has also grown over time. Cross-border M&A has not only increased globally in volume and value, but it also now accounts for a much larger portion of total inward FDI than it did at the beginning of the twentieth century. In the US, for instance, most inward FDI was made up of greenfield investments before World War I, after which the composition of inward FDI gradually “shifted away from greenfield investments and toward mergers and acquisitions” (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006, xvi). By the late 1980s, “foreign takeovers of extant US firms” accounted for most of the FDI coming into the US (Graham & Krugman Reference Graham and Krugman1995, 20).

Yet, while globalization is not a new phenomenon (Dombrowski Reference Dombrowski2005), it is also not linear in its progression. Economic interdependence only recently reached the levels it obtained prior to World War I,32 and scholars caution that the history of the last century implies that the continued progress of globalization is far from inevitable.33 Nye, for example, notes that after

two world wars, the great social diseases of totalitarian fascism and communism, the end of European empires, the end of Europe as the arbiter of world power…economic globalization was reversed and did not again reach its 1914 levels until the 1970s. Conceivably, it could happen again.

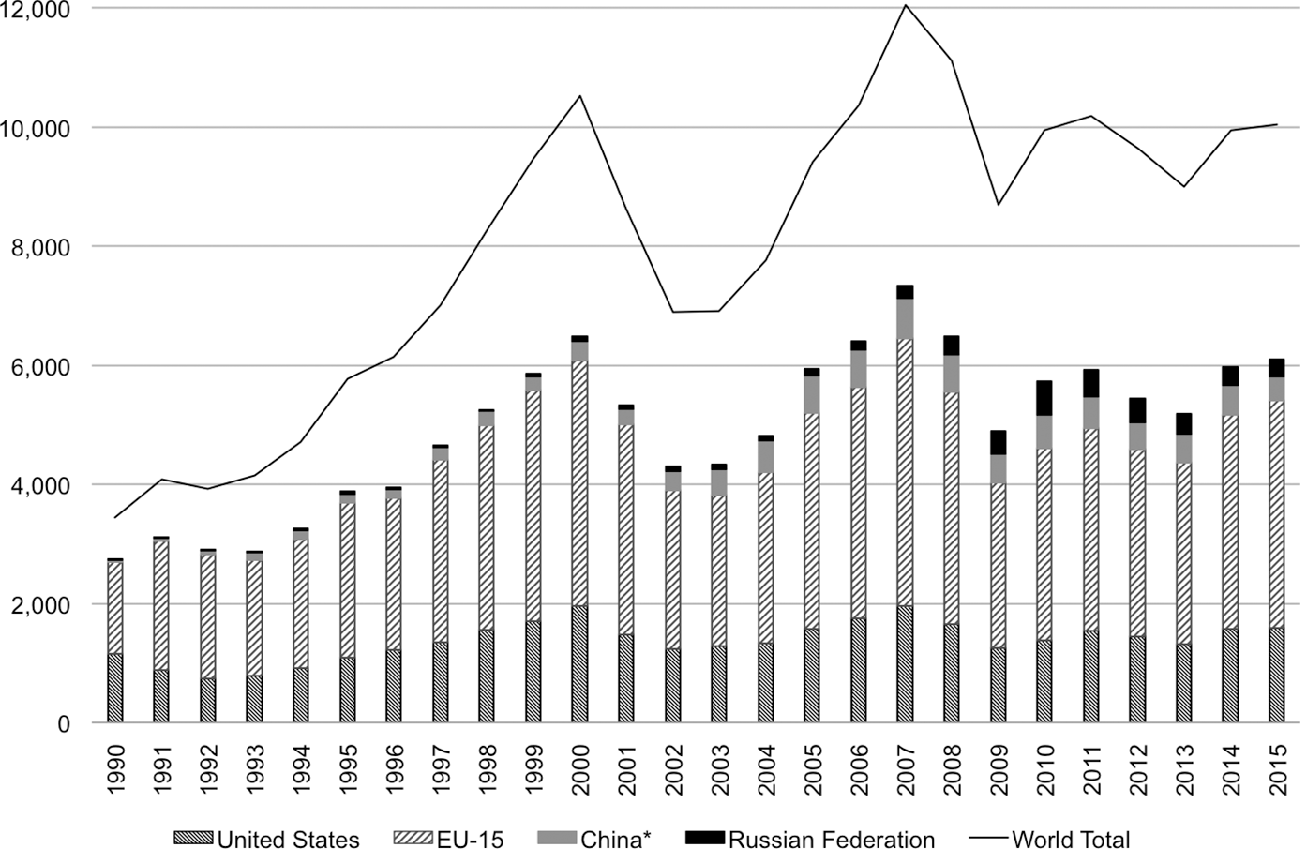

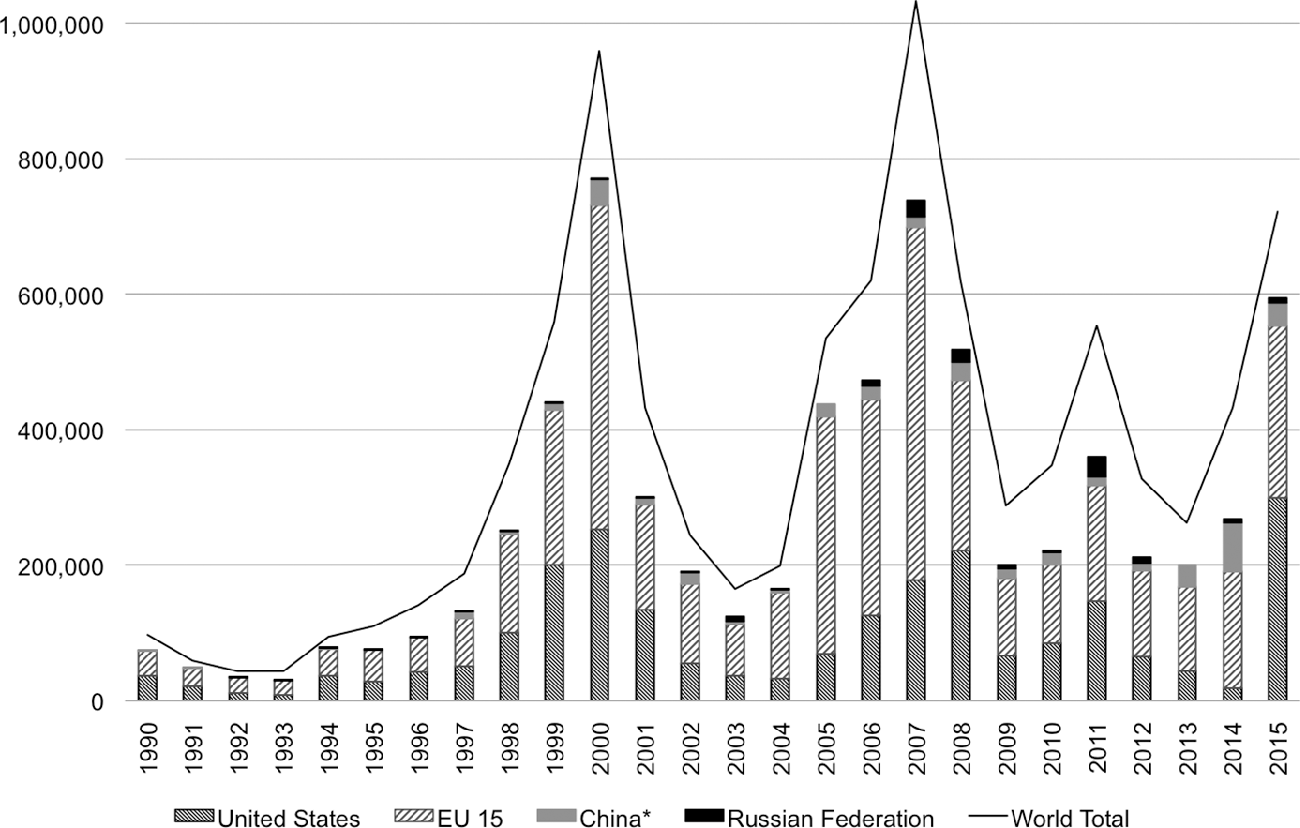

A look at the global picture since the 1990s illustrates the swings that can occur in cross-border M&A activity alone, and the deep impact of the global economic crisis on this activity only serves to illustrate the fragility of the globalization process. Data from the United Nations Commission on Trade and Development's (UNCTAD) 2016 World Investment Report shows an unprecedented surge in foreign takeovers in the late 1990s, culminating in the year 2000 with 10,517 cross-border M&A globally, together valued at almost $960 billion. The post-9/11 period saw a relative drop in activity, and then a rather steady climb to a new high of 12,044 cross-border deals worldwide in 2007, valued at almost $1,033 billion. Cross-border M&A activity then began to slow significantly in 2008 with the onset of the financial crisis, and it has been slow to reach full recovery, with the value of deals in 2015 being just 70% of that in 2007, or almost $311 billion less globally (see Figures 1 and 2).34

Figure 1 Number of cross-border M&A deals (by economy of seller)

Note: China* includes data for both mainland China and Hong Kong.

Figure 2 Value of cross-border M&A deals (by economy of seller in millions of dollars)

Note: China* includes data for both mainland China and Hong Kong.

Of course, a number of possible factors could negatively impact cross-border M&A and the other drivers of globalization, in addition to war and systemic economic crises. Reports by the US National Intelligence Council (NIC) argue that a significant deceleration in globalization could be part of a possible future scenario in which the world's great powers tended toward fragmentation in response to increased levels of threat abroad (NIC 2010, 14), and that a global pandemic, terrorism, or a “popular backlash against globalization” could slow it down or even reverse it (NIC 2004, 30). One NIC report suggests that such a backlash could result from a “white collar rejection of outsourcing in…wealthy countries” or a “resistance in poor countries whose people saw themselves as victims of globalization” (NIC 2004, 30).

The misuse or abuse of state intervention into foreign takeovers could also have a potentially negative impact on cross-border M&A activity. Repeated politicization of foreign takeovers based on contrived or spurious national security concerns combined with rising economic nationalism in one or more powerful countries could even contribute to a backlash against globalization more generally (see e.g., Kekic & Sauvant Reference Kekic and Sauvant2006). This caution may take on a greater sense of urgency, given the deep contraction in international commerce that occurred as a result of the Great Recession that began in 2008, and the rise in populist and economic nationalist sentiment in a number of advanced industrial states marked by political events in 2016.35 For example, Britain's “Vote Leave” campaign during the referendum on EU membership and Donald Trump's campaign for the US presidency both successfully employed anti-globalization rhetoric as part of their platforms, promising a return to domestic control over their respective national economies. Such developments make less surprising the earlier forecast in the NIC's Global Trends 2030 report, which listed as its “most plausible worst-case scenario” a future world in which “the US and Europe turn inward and globalization stalls” (NIC 2012, ii, 135).

Thus, even though economic interdependence has now returned to pre-World War I levels and cross-border M&A appears to be expanding as a key driver of globalization, there is no assurance that economic interdependence and the deeper process of economic integration will continue to be forward-moving. The forward progress of economic globalization requires the presence of a benign hegemonic military power that both desires a liberal economic order and is able to ensure economic integration is possible by signaling its willingness to protect that order (see e.g., Gilpin Reference Gilpin1981).36 Europe's position as the dominant military power ensured the survival of the economically interdependent system it favored before World War I, and the US has played a similar role in the post-World War II era (see e.g., Gilpin Reference Gilpin1981; Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2001).37 Thus, if the US (or other great powers) were to repeatedly misuse intervention into foreign takeovers on national security grounds – not as an act of balancing but as part of a wider domestic backlash against economic globalization – it could be taken as a signal of unwillingness to foster economic liberalization, which in turn could lead to a deeper, if unintended, impact on globalization.38 The theory and cases examined in this book therefore highlight the difference between the use of intervention into foreign takeovers for the purpose of strategic balancing and intervention that might be considered an instance of “overbalancing” or miscalculation.

The Significance

Foreign takeovers play an important role in the globalization process, as states embrace the absolute gains that can be realized through the free movement of capital across national borders. But, as the global economy opens up, new challenges also arise for states – including the fact that some states will use cross-border M&A to take advantage of economic interdependence. For this reason, states maintain the right to, and will, intervene in foreign takeovers to protect their national security.

The purpose of this book is to build a robust theory that explains why states choose to intervene in foreign takeovers on national security grounds, not only when these takeovers originate from within states that are their strategic and military competitors, but also when they originate from states within their own security communities. Such behavior is even more surprising when those security communities are based not only on exceptionally close and long-standing alliances, but also on a commitment to economic liberalization, like the EU or the transatlantic community.

The following chapters outline how states use such intervention as a tool of non-military internal balancing, allowing them to balance the power of other states within the international system without disrupting their broader existing relationships with those states. Foreign takeovers can pose long-term risks and challenges to economic and military power that must be addressed, even within security communities. But states do not intervene in every foreign takeover that poses a possible risk; they must choose which battles to fight. So the answer to the puzzle lies in the fact that with this specific tool of balancing, states can use different levels of intervention appropriate to the threat and context, and that states are more likely to intervene in transactions originating from within their own security communities when there is a combination of both high levels of economic nationalism in the receiving state and some underlying geopolitical tensions or concerns between the two states involved, despite their overall close relationship.

Understanding this behavior is important. First and foremost, it is important because it is about much more than ostensible protectionism, even when economic nationalism may play a secondary role in some interventions. Interventions in foreign takeovers on national security grounds are primarily about power, the balance of power, and the evolution of inter-state competition in the economic sphere. The theory of non-military internal balancing presented here explains why states might feel threatened by foreign takeovers, and how they might respond to preserve their positions of relative power in this context. Policymakers and private actors alike need to recognize this behavior for what it is if they are to avoid costly miscalculations in the future.

Second, while such acts of balancing through intervention into foreign takeovers will, by and large, not affect broader patterns of investment, excessive acts of “overbalancing,” or the repeated misuse or abuse of this tool, could have a negative economic impact on not only the state, but the system as a whole. As already discussed, government-led barriers to cross-border M&A (especially those originating in the US) may pose a challenge to the future of global economic integration if misused or misunderstood. This could be especially true if governments seek to engage in reciprocal overbalancing behavior, using national security arguments to prevent foreign takeovers in even the most benign of sectors. Indeed, if we look at France and Italy's recent efforts to protect national champions in their food industries, or the blurring of the line between national security and the more nebulous concept of “national interest” in some countries, there is some evidence that overbalancing may already be occurring.

This matters because a reversal, or even slowing, of globalization could have a significant and negative economic impact on the global community. Krugman's work indicates that the gains from FDI are manifold, allowing countries to enhance their “comparative advantage” and create “increasing returns to scale,” while leading to “increased competition” and often resulting in “valuable spillovers to the domestic economy” in the form of new technology and more highly skilled workers (Graham & Krugman Reference Graham and Krugman1995, 57–9). A backlash scenario against globalization of the type discussed earlier could not only lead to the loss of these benefits, but also pose a “huge opportunity cost in terms of forgone FDI,” which the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) and the Columbia Program on International Investment (CPII) have placed at “$270bn in FDI inflows per year” globally (Kekic & Sauvant Reference Kekic and Sauvant2006, 14). Given the potential long-term costs of repeated miscalculation, a theory that explains the logic behind legitimate state intervention into foreign takeovers to balance power, and the dynamics surrounding it, may help provide public policymakers with the tools necessary to make better decisions regarding specific foreign takeovers in the future.

Finally, explaining state intervention into foreign takeovers in the most unlikely of cases, within common security and liberal economic communities, may also help deepen our understanding of the theoretical relationship between economic interdependence and levels of conflict within the international system. Liberal theorists tend to view this relationship as positive, expecting lower levels of international conflict as states become increasingly interdependent, the gains from free trade become widespread, and the incentives for conflict are reduced. These observations are one of the very reasons it is so puzzling that barriers to cross-border M&A are being erected between the closest of military and economic allies. Complex interdependence theorists Keohane and Nye (Reference Keohane and Nye2001) caution that while the tendency toward conflict will largely depend on the form that interdependence takes, we should generally expect less military conflict among states tied by extremely high levels of economic interdependence. Consequently, they also note that “conflict will take new forms, and may even increase” as interdependence deepens (Keohane & Nye Reference Keohane and Nye2001, 7) – an insight which may help to explain the puzzle, if the barriers to M&A discussed in this book are considered to be a form of conflict.

Why states are willing to engage in a form of conflict that might itself impede the progress of globalization and economic liberalization that brings not only gains from trade, but also a high level of stability to the system (by decreasing the likelihood of military competition) must still be explained, however. Structural realism suggests that conflict, especially economic conflict, may increase with interdependence (Waltz Reference Waltz1993). But this explanation is both underspecified and vague, providing little or no clarification of what form such conflict will take, and how those forms might vary according to the different relationships between the states in question. It will be the purpose of this book to fill this theoretical gap, and to test the new theory proposed here.

This book will proceed as follows. Chapter 1 provides an in-depth explanation of the theory of non-military internal balancing, and the different ways states can use intervention into foreign takeovers as a tool of this form of balancing. It also outlines the specific hypotheses underlying this argument, which are tested both quantitatively and qualitatively throughout the rest of the book. Chapter 2 explains the statistical methods used to test these hypotheses over a population of cross-border M&A cases, and provides a discussion of the results. Chapter 3 examines four critical cases of unbounded intervention, in which different states sought to block a foreign takeover in order to maintain their positions of relative power within the international system. Chapter 4 covers a fifth critical case of unbounded intervention, the DPW/P&O deal, which I argue is an outlier case that provides an excellent example of overbalancing. Chapter 5 investigates two cases of bounded intervention, where states mitigated a cross-border M&A transaction to maintain their power. Chapter 6 considers two cases of “non-intervention” and one of “internal” (or indirect) intervention, where the state involved encouraged a domestic white knight to acquire a vulnerable national champion in order to obviate the need for direct intervention in an unwanted foreign takeover. Finally, the Conclusion discusses the theoretical and practical implications of my findings, and provides a deeper examination of their significance for theory and practice.