Introduction

Bounded (like unbounded) intervention is a type of non-military internal balancing. Its primary objective is to balance another state's power, without fundamentally disrupting the overall diplomatic relationship with that other state. Bounded and unbounded intervention are also motivated by the same factors: i.e., economic nationalism and/or geopolitical competition concerns. The purpose of this chapter is not only to confirm the validity of the primary and secondary hypotheses posited in Chapter 1, but also to clarify how bounded intervention is different from unbounded intervention. In other words: what does it entail, and when and why will a state employ this balancing strategy?

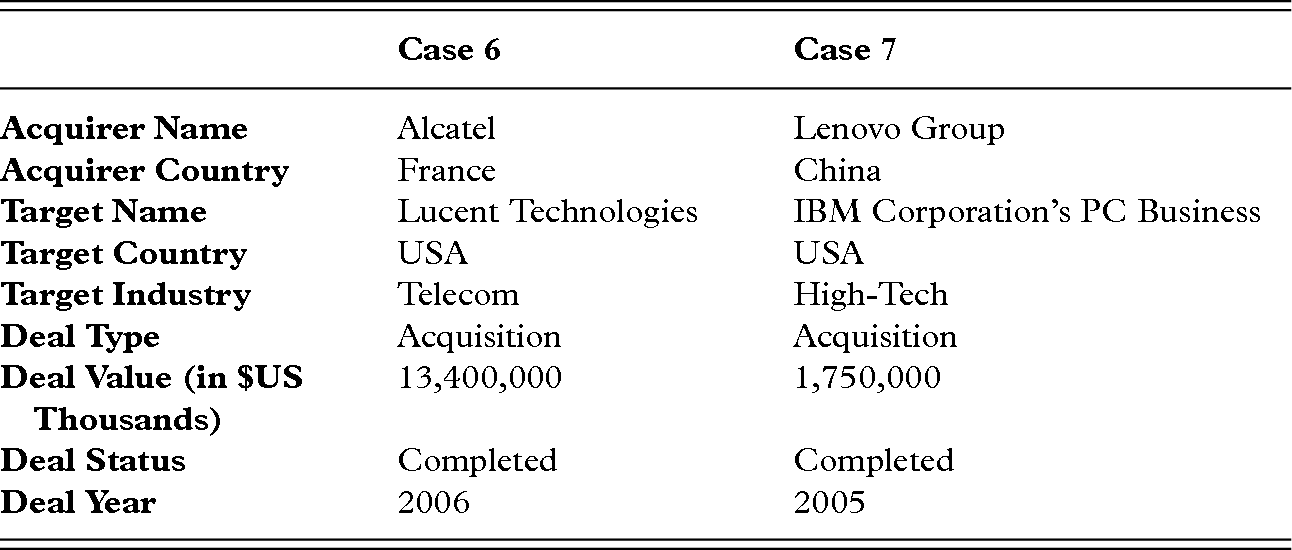

This chapter begins by refining the definition of bounded intervention and identifying the government actions and methods that characterize it. The motivations for bounded intervention are then revisited, followed by an in-depth examination of two further critical case studies: the takeover of America's Lucent Technologies by France's Alcatel and that of IBM's American PC Business by China's Lenovo. Figure 28 provides an overview of these cases, which were chosen for their vital importance to a proper understanding of bounded intervention and their ability to provide further insight into the statistical results presented in Chapter 2. At the end of this chapter, it should be clear what bounded intervention is, what motivates it, and why governments choose to use it.

| Case 6 | Case 7 | |

|---|---|---|

| Acquirer Name | Alcatel | Lenovo Group |

| Acquirer Country | France | China |

| Target Name | Lucent Technologies | IBM Corporation's PC Business |

| Target Country | USA | USA |

| Target Industry | Telecom | High-Tech |

| Deal Type | Acquisition | Acquisition |

| Deal Value (in $US Thousands) | 13,400,000 | 1,750,000 |

| Deal Status | Completed | Completed |

| Deal Year | 2006 | 2005 |

Figure 28 Bounded intervention: critical cases

Defining Bounded Intervention

Definitions

The difference between bounded and unbounded intervention lies largely in degree, intensity, and intent. With unbounded intervention, the intent of the government in question is to block a deal through whatever means are necessary. Further, the government believes such action is necessary to resolve its concern over relative power positions, regardless of whether it is economic nationalism or geopolitical factors that have motivated that concern. However, when the government believes the circumstances of a particular deal make it possible to resolve its concerns through a more limited form of intervention, it will often take the opportunity to exhibit restraint by using the bounded alternative instead. This is because bounded intervention is even less likely to produce antagonism in the general relationship between the states involved.

With bounded intervention, the state employs a restricted (and hence “bounded”) strategy, the intent of which is simply to modify a cross-border deal in its favor, rather than to block it in its entirety. In other words, the state's intent is to allow the cross-border deal to occur, but in a modified form, which it has shaped. The means of modifying, or “mitigating,” a deal naturally varies in accordance with concerns raised by the host government of the target company (state A). So, too, will the level of bounded intervention that the government feels it is necessary to employ. This section seeks to differentiate between the two levels of bounded intervention: high and low. It also identifies some of the methods governments have at their disposal to “mitigate” the negative effects of a deal in the interest of state security, as that state defines it, though the list of possible government concerns and solutions is theoretically endless.

A hypothetical example will elucidate the basic difference between high- and low-bounded interventions. Let us assume that state A is concerned by the inclusion of a certain corporate division in a cross-border transaction – perhaps because it retains government contracts, is the primary manufacturer of a significant piece of military technology, or plays an important role in the military-industrial complex of that state. There are a number of ways that state A might handle this concern, depending on the sensitivity of the technology involved, the nature of the government contracts, and the degree of concern that these factors raise vis-à-vis national security.

If state A is exceptionally worried about the implications of the inclusion of this corporate division in the transaction, as well as the intentions and reliability of the company and/or country involved in the takeover, it might choose a high level of bounded intervention. High-bounded intervention entails the imposition of severe or exceedingly restrictive changes on the transaction in question, and may even require unique measures. For instance, state A might pursue a formal arrangement by which the division in question remains entirely run and controlled by nationals of state A, allowing only the revenue of that division to go to the acquiring company in state B. Alternatively, state A might go so far as to request that the division be excluded entirely from the sale of the domestic company.

The government of state A may, however, choose to engage in a low level of bounded intervention if it feels that severe measures are unnecessary to protect its national security. Low-bounded intervention entails simpler, less intrusive actions, which are not necessarily unique to the deal in question. For instance, in the hypothetical transaction under discussion, state A might feel that it is an adequate solution to simply require the acquiring company to respect its export control laws, and not pass on the technology involved in the deal to countries it deems “unfriendly.” Alternatively, if the acquiring company comes from a country that is a close ally and economic partner of state A, it may have already signed a comprehensive security agreement as the result of high-bounded intervention in a previous transaction. In that case, state A may simply rely on that previous agreement to resolve its concerns, necessitating only a low level of intervention in the current transaction.

A real-life example of this latter type of case would be when the UK's BAE Systems purchased America's United Defense Industries (UDI) in 2005. BAE Systems has purchased a number of US companies in the past through its US subsidiary BAE Systems North America. The US government had, in previous deals, asked BAE Systems North America to sign a comprehensive set of security agreements. Thus, one industry analyst has pointed out that when the BAE/UDI takeover occurred, only minimal intervention was required on the part of the US government because, even though UDI was a major government supplier with sensitive technology, the earlier agreements signed by BAE would allay the majority of the security concerns inherent in the UDI transaction.

No matter what level of bounded intervention a state chooses to employ, it will usually ensure that the modifications it makes to a deal are made legally binding upon the companies involved. In other words, the contracting parties (the acquiring and target companies) will be asked to sign a legal document (or series of documents) enumerating the ways in which the government has chosen to mitigate the negative effects of the deal, and confirming the contracting parties’ willingness to be bound by those modifications and requirements. In the US, for example, the government is unlikely to be satisfied with such agreements unless it “believes that the risks it identifies can be managed” successfully through deal modifications and assurances agreed to by the acquiring company (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006, 71–2). Indeed, in any country, in order to be satisfied with this more restricted form of intervention, the government must be confident that the changes made to the deal will effectively protect its national security and, in some cases, its economic position, if that state believes economic security to be tied to national security.

In summary, bounded intervention is a restricted type of intervention used as a form of non-military internal balancing, where the goal is once again to protect or maximize the economic and/or military power of the state, without damaging the greater meta-relationship between the states involved. Such intervention allows cross-border M&A activity to continue, while preventing foreign governments – through the market actions of companies that they may either wholly control or later gain influence over – from gaining access to sensitive technology or information, or from gaining control of resources, materials, and networks, that could eventually help to alter the economic and/or military power balance.

Different States, Different Means…

The exact method and means through which a bounded intervention is executed varies by country. For example, the level of institutionalization of the procedures for intervention, the tools available for intervention, and the formality of the agreements negotiated between the government and the companies in question can differ substantially depending on the country involved. Before moving to the case studies, it is therefore important for comparison to examine how bounded intervention is effected in four different countries – the US, China, Russia, and the UK – both during the case studies and at the time of writing. A brief overview is also provided of the overarching foreign takeover regimes in these countries (with the exception of the US, whose regime was comprehensively examined in Chapter 3, pp. 110–11), in order to place these different approaches to bounded intervention in context.

The United States

In the US, the foreign takeover review process, and therefore the process through which a deal might be mitigated, is highly institutionalized. Throughout the course of a proposed takeover for a US company, the foreign acquirer and the domestic target companies will regularly consult with CFIUS, often even before the formal review process begins. During the course of this interactive process, CFIUS may raise its concerns with the companies on an informal basis, allowing them to address an issue before it is formally raised as part of the Committee's official investigation. According to Graham and Marchick, the government agencies represented within CFIUS may also contact the parties directly. They explain, for example, that the DOD may “negotiate mitigation measures with the transaction party,” “if [it] believes that the risks [to national security] it identifies can be managed” successfully through alterations to the deal, or through other assurances agreed to by the acquiring company (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006, 71). They reveal that such measures “generally fall into four categories (in ascending order of restrictiveness)” (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006, 71–2). These measures include: (1) some form of “board resolution” to ensure citizens of the target state remain involved in management, (2) the creation of a “limited facility clearance” to restrict foreign access to secure areas or technology, (3) a “Special Security Agreement (SSA)” or “Security Control Agreement (SCA)” that enumerates a series of security measures to be followed by the acquirer, and (4) a “voting trust agreement” or a “proxy trust agreement” (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006, 71–2). CFIUS may, on its own, also impose mitigatory measures as part of a national security agreement, which it can ask the contracting parties to sign before recommending a deal to the President for approval. Such national security agreements may include onerous changes or modifications to a deal, or may seek more simple assurances that the company in question will adhere to US export control laws and other industrial and security regulations. More severe and involved actions are considered to be cases of high-bounded intervention. In rare cases, companies might be forced to divest a portion of the target company. On one extraordinary occasion, in the Alcatel/Lucent case examined in this chapter, the government reserved the right to force a future reversal of the takeover if the acquiring company fails to adhere to the assurances it made to the US government regarding measures to safeguard US national security.1

Thus, while the US process is not completely transparent, it is highly institutionalized and fairly straightforward to navigate for those companies that wish to make a deal work. Bounded interventions occur within a recognized, established, and coherent legal framework, which can easily be adapted to handle different threats to national security.

China

Relative to the US, the foreign takeover review process in China is not as highly institutionalized, predictable, or consistent (see e.g., Stratford & Luo Reference Stratford and Luo2015; US GAO 2008, 42–52). As China has moved toward a more open economy, and since its accession to the WTO in 2002, the Chinese government has sought to reform and clarify the FDI laws and regulations in its country in order to bring them in line with WTO members’ expectations. Yet, the laws and regulations applicable to foreign investors can be difficult to follow, and can vary depending on the type of foreign investment made and the type of purchasing vehicle used to make it. In fact, by 2008, China reportedly had “more than 200 laws and regulations that involve foreign investment” (US GAO 2008, 45), and, by 2017, more than 1,000 of them (US DOS 2017). For example, the Company Law of the PRC,2 the Takeover Rules,3 and the Securities Law4 apply to both domestic and foreign public M&A (Jian & Yu Reference Jian and Yu2014, 2), while the basis for the body of regulations covering foreign M&A of Chinese companies lies in the 2002 Provisions on Guiding the Orientation of Foreign Investment5 and the 2006 Provisions for Mergers and Acquisitions of Domestic Enterprises by Foreign Investors (amended in 2009).6

The 2004 Decision on Reforming the Investment System outlines the instances in which investment deals are “encouraged, restricted, and prohibited by the state,” though it only provides general “guidelines” as to which industries might be included in these broad categories.7 The Catalogue for Guiding Investment in Foreign Industries provides more detailed guidance on this topic. First released in 1995, the Catalogue has been reissued in 1997, 2002, 2004, 2007, 2011, 2015, and 2017 (CECC 2012; Koty & Qian Reference Koty and Qian2017), and lists those industries that fall within the encouraged, restricted, and prohibited categories for foreign investment. In 2017, this included thirty-five restricted and twenty-eight prohibited industries, with the latter category including industries ranging from the mining of rare-earth metals to the retail of tobacco products.8 In the past, it was assumed, but not explicitly stated, that foreign investors were generally permitted to invest in those industries not listed, with special rules for some regions and sectors (Qian Reference Qian2016, 6–7). The 2017 Catalogue, however, explicitly states that it is now to be used nationwide as a “negative list for foreign investment.”9 This means that prohibited industries “are completely closed to foreign investment,” and that restricted industries “are subject to restrictions such as shareholding limits, and must receive prior approval from MOFCOM.” All other industries not appearing on this negative list now “do not require prior approval from MOFCOM,” though they “are still subject to record-filing requirements” (Koty & Qian Reference Koty and Qian2017, emphasis added). That being said, the Catalogue is far from simple or comprehensive, as particular regions and sectors may still have additional restrictions on foreign investment (see Koty & Qian Reference Koty and Qian2017). Notably for our discussion here, the Catalogue generally “prohibits foreign investment in sectors that China views as key to its national security,…[but] does not prohibit investment for stated reasons, or define national security” (US GAO 2008, 44).10

Anti-trust competition review of M&A has also evolved and become more institutionalized over time, bringing with it more formal mechanisms through which the Chinese state can intervene in foreign takeovers on national security grounds. In the time period covered by the database (2001–07), China had several laws that included “antitrust provisions and prohibitions on anti-competitive conduct,” but these were “fragmented, confined in scope, and rarely enforced” (Ha & O'Brien Reference Ha and O'Brien2008). The 2003 Interim Provisions on Mergers and Acquisitions of Domestic Enterprises by Foreign Investors, and the 2006 Provisions that replaced it, prohibited foreign takeovers that would result in unacceptably high market concentrations or ultimately restrict competition, but the Provisions did “not specify any penalties,” and in most cases there was “no follow-up” (Ha & O'Brien Reference Ha and O'Brien2008). In 2007, the Chinese government passed a comprehensive Anti-Monopoly Law (AML), implemented in 2008, which in contrast includes broad powers to review the competition effects of both domestic and cross-border M&A transactions and institutes enforceable penalties for non-compliance with government decisions regarding a particular transaction (Ha & O'Brien Reference Ha and O'Brien2008; Wang & Emch Reference Wang and Emch2013). The Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), and the State Administration of Industry and Commerce (SAIC) implement and enforce the AML, with MOFCOM handling merger control (Wang & Emch Reference Wang and Emch2013).11

In addition to the ability to review a foreign investment on competition grounds, the 2008 AML notably included the first institutionalized regulatory mandate for the Chinese government to review a foreign investment on national security grounds, under Article 31 of its provisions.12 Though, as demonstrated in the Macquarie/PCCW case, an informal process of intervention operated during the 2001–07 period covered in the database (see Chapter 3). China then established a more formal security review of foreign takeovers in 2011 with the Circular of the General Office of the State Council on the Establishment of Security Review System Regarding Merger and Acquisition of Domestic Enterprises by Foreign Investors13 and the subsequent associated implementing provisions.14 The 2011 Circular created a Joint Commission to undertake these reviews, led by MOFCOM and the NDRC under the oversight of the State Council (see US DOS 2017). This review process examines the “national security” implications of a proposed foreign takeover, as well as the potential impact of a transaction on “steady economic growth,…the basic social living order, and…the R&D capacity of key technologies involving national security” in China.15 Deals subject to the security review process are those that involve

acquisitions of a controlling interest in a PRC enterprise within a sensitive sector, such as key agriculture, key energy resources, key infrastructure, key transport systems, key technology and critical equipment manufacturing sectors, which may affect national security; or acquisitions by a foreign investor of any stake in a PRC military or military supportive enterprise, any enterprise located in the surrounding area of important or sensitive military facilities and any other enterprise which is of importance to national defence security.

The Chinese national security review process is modeled loosely on the CFIUS process, with an initial review period, followed by a more extensive special review if a relevant government department believes the deal may affect Chinese security. Parties involved in the deal also file voluntarily for a review with MOFCOM, or the deal can be referred to MOFCOM for review by “other government agencies, or…third parties” (Jalinous et al. Reference Jalinous, Nègre-Eveillard and Heinrich2016, 5). Parties may not withdraw their application for approval under this review system without “MOFCOM's prior consent,” however, and there is no administrative appeals process or avenue for judicial review of MOFCOM decisions (Jalinous et al. Reference Jalinous, Nègre-Eveillard and Heinrich2016, 6).

In China, both unbounded and bounded intervention are possible, though the level of formalization and institutionalization of the methods used to intervene has increased over time. The 2011 Circular, for example, now clearly provides that when a foreign acquisition or merger is believed to impact national security, MOFCOM or another relevant government department can veto the deal or modify it by “transferring related equities, assets or [taking other measures] to eliminate the effect of [the deal on] national security.”16 In other words, once a deal goes through the review process, MOFCOM can approve it, mitigate it (bounded intervention), or veto it (unbounded intervention). Moreover, if MOFCOM is made aware of a foreign takeover that has been completed without having voluntarily filed for approval, and it raises national security concerns, MOFCOM has the authority at that point to apply “sanctions or mitigation measures, including a requirement to divest the acquired Chinese assets” (Jalinous et al. Reference Jalinous, Nègre-Eveillard and Heinrich2016, 6). Once the foreign takeover is completed, the new entity must then register as a foreign-invested enterprise (FIE) (ABASAL 2015, 43–4).

It should be noted, however, that the approval process may vary according to the specific nature of the deal, as the acquisition of a Chinese firm can take place through a number of different routes and via various types of acquisition vehicles.17 Most deals of the size and sector examined in this study will likely require government approval from MOFCOM,18 though foreign investment in financial institutions is covered by a different set of regulations and approval authorities (see Chan et al. Reference Chan, Zhou and Fong2015b; Linklaters 2015), and some deals – depending on the size, vehicle used, and sector involved – may also require additional local and/or regional approvals (US GAO 2008, 46). There are also additional rules and regulations that might apply to foreign investments.19

It should be noted that further changes have been proposed and made to the Chinese foreign investment review process in 2015 and 2016 that, while offering further clarity to foreign investors, may also increase the opportunities for Chinese state intervention in both bounded and unbounded form. At the beginning of 2015, China released a Draft Foreign Investment Law looking at the possibilities for streamlining and reforming its foreign investment regime. It was in this Draft Law that China first considered extending national treatment to FIEs for investments beyond those restricted or prohibited in a negative list (US DOS 2016a), a policy that appears to have come to fruition with the 2017 Catalogue (US DOS 2017). The Draft Law also proposed changes to the national security review process, including a “broader scope of application…to any foreign investment that endangers or may endanger national security, regardless of structure and degree of control by the foreign investor” (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Zhou and Huang2015a, 6). In May 2015, the Trial Measures for the National Security Review of Foreign Investments in Pilot Free Trade Zones introduced a new security review process for the FTZs, likely as a trial for later national use, which broadened the definition of national security and widened the scope of security reviews “to include greenfield projects” (Stratford & Luo Reference Stratford and Luo2015, 3–4; US DOS 2016a).20 In July 2015, the National Security Law of the PRC was adopted, which broadened the scope of national security reviews nationally, “to include an investment's impact on cultural security, information security, industrial security, military security, technological security, and territorial security, among others” (US DOS 2016a).21 Further implementing legislation was not published at the time of writing (Jalinous et al. Reference Jalinous, Nègre-Eveillard and Heinrich2016), but it seems that all of these actions are intended to “reinvigorate the national security review system [and] seem to signal the awakening of a rather dormant regime that existed under the [2011] Circular” rules (Stratford & Luo Reference Stratford and Luo2015, 5).

In 2016, China also adopted and implemented the Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress on Amending Four Laws Including the Law of the PRC on Foreign-Funded Enterprises,22 reforming part of the FDI system in China. It amends laws pertaining only to foreign investments made by FIEs23 in permitted sectors not covered by the Catalogue, which now is treated as a negative list for investment made by FIEs (Ye Reference Ye2016). This reform does not yet alter the national rules described earlier that apply to wholly foreign investors purchasing domestic Chinese enterprises (Cai Reference Cai2016, 1; Livdahl et al. Reference Livdahl, Sheng and Liu2016, 2). The foreign M&A approval process, national security review process, and competition process under the AML, for example, remain in place at the time of writing. It is expected that reform may occur among these processes, but that such reform will allow for greater ease of FDI in those sectors desired by the Chinese state, while also allowing China greater maneuverability to block and/or modify deals to protect Chinese interests and the very “broad definition of national security” set out in the 2015 National Security Law (Stratford & Luo Reference Stratford and Luo2015, 5).

In sum, the purpose of all of these decrees has been to create a legal regime meant to protect China's strategic and economic security by ensuring the government's ability to modify cross-border deals to protect Chinese interests (see e.g., Stratford & Luo Reference Stratford and Luo2015; US GAO 2008, 42). The changes have not necessarily increased the transparency or efficiency of the review process, but have demonstrated a trend toward greater bureaucratic protection of China's self-defined strategic interests, in addition to a higher level of economic protectionism.

Thus, there is wide latitude for the Chinese government to engage in bounded intervention, and clearly identifiable means through which the state might mitigate a deal in order to reduce any perceived or potential threat to national security. MOFCOM, the evolving security review process, and various local reviews, all provide opportunities for the government to request that changes be made to a deal in order to place it in line with Chinese interests. The latitude for the government to make, or encourage, any modifications to a deal that it deems necessary is enhanced by the complexity of FDI legislation (see US GAO 2008, 42–50). Foreign investors can find it difficult to understand “when central versus local rules apply,” or when particular regulations are more likely to be enforced (US DOS 2016a). Therefore, Chinese review authorities essentially have the latitude to decide how a deal must be structured in order for it to comply with Chinese strategic interest, if they desire to do so. Companies seeking approval for their transaction then have the choice whether or not to adjust to those demands. These conversations are rarely made public, however, helping to explain the extremely low levels of data available on bounded intervention in China.

Russia

The foreign takeover process is perhaps even less transparent and institutionalized in Russia. Officially recognized by the US and EU as a working market economy in 2002, Russia acceded to the WTO in 2012 and has been slowly opening itself to foreign investment over time. The 1999 Federal Law No. 160-FZ on Foreign Investment in the Russian Federation, in conjunction with the 1991 Investment Code, are intended to “guarantee that foreign investors enjoy rights equal to those of Russian investors” (US DOS 2016b). Yet, Russia has also “set foreign ownership caps in industries or individual companies in what are considered ‘strategic’ or sensitive sectors, including the power and gas monopolies, banking, insurance, mass media, diamond mining, and civil aviation” (EIU 2003, 14). The Russian government also maintains strategic stakes in what it calls “the natural monopolies,” such as the oil and gas sectors, “for the sake of stability and national security” (EIU 2003, 10). In many instances, however, the laws surrounding foreign investment and ownership caps have “not always [been] enforced in practice” (US DOS 2015, 3), and the purchase of assets and the takeover of private companies have remained possible in some of the industries examined in this book.

During the time period covered in this book's dataset, from 2001 to 2007, the national security review process had not yet been formalized in law, and intervention into foreign takeovers was made on a case-by-case basis. For the industries covered, a fundamental requirement for a foreign takeover at the time was that it comply with Russian anti-competition rules, and thus that the “acquisition of more than 20% of a company's stock requires prior approval of” the competition authority (IFLR 2002). In the early 2000s, this was the Ministry of the Russian Federation on Antimonopoly Policy and Support to Entrepreneurship (MAP), which was replaced in 2004 with the Federal Antimonopoly Service (FAS). In 2006, Federal Law no. 135-FZ On Protection of Competition was adopted, which “reflected the existing system of anti-monopoly regulation” (FAS 2015, 16).24

Yet, the attitude toward foreign investment arguably took a distinct inward turn in 2003/04 following the downfall of the oil company Yukos. After that incident, Russian government intervention into foreign takeovers in these sectors tightened under then President, and later Prime Minister, Vladimir Putin. As one industry source noted, there was little formality to the review process at the Anti-Monopoly Ministry during this period, and takeovers of assets deemed to be strategic by Putin were often subject to an additional review by the relevant government authority or ministry (Interview 2008a). This appears to be clearest in the energy and natural resources sectors, where Putin has sought to maintain control over certain resources in order to use them as a tool for Russian policy and the furtherance of Russian power. Furthermore, by 2008, it was clear that any energy deal involving a foreign investor would only get approval if 51% of the new entity were to be owned, or designated to eventually be owned, by Russian citizens – a trend that seemed to affect other strategic sectors as well (Interview 2008a). This is clearly one rather blatant way in which the Russian government has sought to mitigate the proposed foreign takeovers of certain companies it believes to be tied to its nation's future security – a strategy which, at the time of writing, it still seems to employ in a variety of industries, companies, and circumstances.

An excellent example of this is provided by the 2007 EniNeftegaz-Arktikgaz case. In this case, a JV company (EniNeftegaz) owned by two Italian energy companies (Eni and Enel) bid for 100% of the assets of the gas production company Arktikgaz in a public auction. The Italian JV was allowed to take over the assets by the Russian authorities upon winning the auction, but it is clear that this was only allowed to happen because a preliminary deal had been forged with the Russian gas giant Gazprom, whereby Gazprom would eventually control the assets. The companies “negotiated” an agreement in advance whereby Gazprom retained “the option to buy a 51% stake in [Arktikgaz]” (Global Insight 2007). Furthermore, Dmitry Medvedev – then Chairman of Gazprom's Board, and President of Russia only a year later – was quick to announce “that Gazprom plans to exercise the option” to buy the controlling stake (Global Insight 2007). One member of the beleaguered Russian legal community made it plain that this was not a case of “open, free auctions but rather [of] organized sales at knockdown prices…with predetermined winners,” where “in reality Gazprom,” a Russian government controlled entity, “is the winner” (Global Insight 2007). This case highlights the desire of the Russian government to ensure that its most strategic companies remain domestically controlled, making it clear to foreign investors that foreign takeovers are only likely to be allowed to occur in strategic sectors when they have been mitigated in such a manner.

In 2008, just after the time period covered in the database, Russia adopted a more formalized national security review process for screening foreign investments in designated strategic sectors, but, importantly, the dynamics of Russian intervention into foreign investment appear to remain largely the same. In April 2008, Russia adopted Federal Law No. 57-FZ on Procedures for Foreign Investments in the Business Entities of Strategic Importance for Russian National Defense and State Security,25 often referred to as the Strategic Investments Law. This law established a Government Commission for Control over Foreign Investments, chaired by the Russian Prime Minister, which must pre-approve foreign investments into designated strategic sectors and above particular ownership thresholds that vary by the type of foreign investor and sector involved. In other words, attempts by foreign investors to gain controlling stakes, much less complete ownership, over a company in an industry associated with national security in Russia must be approved by the committee. This law has been periodically amended, notably in 2011 and 2014, but again remains broadly consistent in its approach.26 It was reported that “as of April 2015, 45 activities require government approval for significant foreign investment” (US DOS 2016b, 3). These include, but are not limited to: aerospace and defense sectors, such as the production and development of munitions, armaments, and aviation equipment; media and telecommunications, such as printing activities, broadcasting, and fixed-line telephone communications; energy and natural resources, such as nuclear energy and specially designated subsoil areas for natural resource extraction given federal status; and so-called “natural monopolies” (see Article 6, Strategic Investments Law; Syrbe et al. Reference Syrbe, Pavlovich and Nogovitsyna2014, 2). It should be noted that under separate legislation in 2014, Federal Law no. 305-FZ simply caps foreign ownership of Russian media companies at 20% (US DOS 2016b, 3).

Investment thresholds triggering a national security review by the Commission for Control over Foreign Investments varies, as already mentioned, by type of investor and sector, with some of the latter subject to separate legislation. For state-controlled foreign investors, like state-owned enterprises (SOEs), investments in over 25% of a Russian company in most strategic sectors will trigger the need for a review, investments in over 5% of a subsoil block with federal status will trigger a review, and any “acquisition of over 50% is prohibited” in a strategic sector (Stoljarskij Reference Stoljarskij2011, 79), making it virtually impossible for a foreign state-controlled investor to undertake a complete foreign takeover and merger in a strategic sector in Russia. For a private foreign investor, a review is generally triggered if over 50% of a company in a strategic industry, or over 25% of a subsoil block with federal status, is acquired; review will occur at lower levels of investment if they result in influence or control over the decision-making processes in a company in a strategic industry (Stoljarskij Reference Stoljarskij2011, 79; Reference Stoljarskij2012, 2). Once a company files, its application is registered and examined to see if it is, in fact, necessary to proceed with a detailed review. The application is returned to the investor without further review if the investment is either clearly prohibited under the law or doesn't meet the requirements for review (Stoljarskij Reference Stoljarskij2011, 81). If a review is required, and the investor does not withdraw from the process, an investment may be approved, denied (unbounded intervention), or mitigated (bounded intervention). In the latter case, “condition[al] consent [may be given] subject to the applicant's discharge of specific obligations,” such as the “maintenance of specific production sectors, [or] the continued discharge of specific state orders” (Stoljarskij Reference Stoljarskij2011, 81). Deals not submitted for approval are rendered “null and void,” and the parties involved will be subject to penalties (Stoljarskij Reference Stoljarskij2012, 2). Negative decisions by the Commission can be appealed in court under the Strategic Investments Law, but as of May 2014, no investors had yet done so (Syrbe et al. Reference Syrbe, Pavlovich and Nogovitsyna2014, 7; Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 70). From the establishment of the Commission and formalization of the national security review process in 2008,

the Commission has received 395 applications for foreign investment (as of March 11, 2016). Of that total number, 150 were recognized as transactions for which approval was not required; 43 applications were withdrawn by applicants; and seven had not been completed. Of the 195 applications that the Commission reviewed, 183 were approved (93.8 percent), including 49 with certain conditions. Only 12 applications (6.2 percent) were rejected.

While the outright veto rate is not too high, the restrictions in strategic sectors erect significant barriers to foreign investment of the type examined in this book – and a number of deals are clearly modified to ensure the continued control and influence of the state and the protection of national security in these sectors.

In summation, there is now a more regularized and somewhat more transparent process for the national security review of foreign investments in Russia, but the dynamics behind this process – intended to protect Russian control of strategic industries and companies, while encouraging the “foreign investment and technology transfer…critical to Russia's economic modernization” – has remained consistent over the time period covered in the database and up to the time of writing (US DOS 2016b). There is, after all, no published or public set of criteria used by the Commission in its review process to assess what might actually constitute a risk to nation security, giving the Commission extra leeway in how it approaches foreign investment in relation to state security and strategy, and making it difficult for investors to foresee which deals might be considered to have a “strategic element” (Syrbe et al. Reference Syrbe, Pavlovich and Nogovitsyna2014, 1; Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016 30). Moreover, concerns over the unpredictability of the process, and over a “Russian investment climate…marked by high levels of uncertainty, corruption, and political risk,” also continue through to the time of writing, and “are unlikely to improve in the near term” (US DOS 2016b, 1; see Stoljarskij Reference Stoljarskij2012; Syrbe et al. Reference Syrbe, Pavlovich and Nogovitsyna2014).

The United Kingdom

The UK provides yet another example of the many different national approaches to bounded intervention that are possible. For the time period covered in this book, the UK has arguably represented one of the most open economies to FDI, though it is possible that this degree of openness may be subject to change in the future.

Until 2002, foreign M&A were subject to the 1973 Fair Trading Act (FTA), which supplied the framework for the competition review of all mergers in the UK. Section 84 of the FTA “set a broader public interest test” to be considered by those making decisions as part of this process, including, for example, whether a proposed transaction would have an effect on “maintaining and promoting the balanced distribution of industry and employment in the United Kingdom” (Seely Reference Seely2016, 9). Toward the end of the FTA regime, however, “most merger decisions were already focused on competition” alone, rather than on wider considerations (Seely Reference Seely2016, 9). The FTA was replaced in 2002 with the Enterprise Act, which, as of November 2016, provides the framework for the review process for all M&A in the UK. This act, as amended, establishes an anti-trust review that is triggered for deals that reach certain thresholds: transactions that would result in an entity with over £70 million in turnover, or which would have a post-transaction market share of over 25% (Seely Reference Seely2016, 4). These competition reviews were originally handled by the Office of Fair Trading and the Competition Commission, and since 2014 have been handled by the body into which these entities were merged: the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA).

Section 58 of the 2002 Enterprise Act provides for the only instance in which the Secretary of State can intervene in the M&A review process. It “allows for the Secretary of State to intervene in mergers where they give rise to certain specified public interest concerns: specifically, issues of national security; media quality, plurality & standards; and financial stability” (Seely Reference Seely2016, 3).27 When the market share and turnover thresholds triggering the general merger review are not met, “the Secretary of State may [also] intervene in a very limited range of ‘special public interest cases,’…where one of the enterprises concerned is a relevant government contractor…in defence mergers, or where the merger involves certain newspaper or broadcasting companies” (Seely Reference Seely2016, 6). As in many other countries, concerns over national security or the public interest will trigger a further investigation, in the UK called a “phase 2 investigation,” after which the Secretary of State makes the final decision over whether to approve the deal, prohibit it, or mitigate the concerns raised by the transaction by making it subject to certain “conditions related to, for example, security of supply or security of information” (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 72). The entire review process may take up to six or nine months, and decisions can be appealed through both administrative processes and judicial review (Wehrlé & Pohl Reference Wehrlé and Pohl2016, 72). Interestingly, the 1975 Industry Act also “provides the UK government with the authority to intervene when the takeover of important manufacturing concerns by nonresidents is against the national interest” (GAO 1996, 40).

For the time period covered in this book, and up to the time of writing, the UK has not hesitated to engage in bounded intervention when it feels that it is necessary to preserve national security. Indeed, the Department for Business Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR), and later its replacement the Department for Business, Innovation, and Skills (BIS), even maintained a list of the most serious potential “mergers with a national security element” on its website, and provided the legal documentation given to justify intervention in those cases, as well as documentation of the undertakings made by companies in respect to the conditions imposed on the deals.28 While this list only seems to have related to those mergers in the aerospace and defense sector, despite clear evidence of intervention in other strategic sectors, such transparency regarding the details of bounded intervention, even in one industry, is extremely rare, and is a sign of the UK's valued commitment to an open FDI regime. In 2016, BIS was replaced with the Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), and this information can still be found using the search function on its website, or on the archived BIS website.

A good example of how bounded intervention is achieved in the UK is provided by the Finmeccanica/BAE case. In 2005, the Italian aerospace and defense company Finmeccanica sought to buy BAE Systems’ avionics and communications businesses, which had a close relationship with the UK military community. The Secretary of State29 determined the deal

might adversely affect the public interest on national security grounds as a result of both the communications and avionics business transferring to the ownership and control of an overseas company. The MoD has identified two main areas of concern arising from this merger: the maintenance of strategic UK capabilities and the protection of classified information.

The government intervened and negotiated a solution with the two companies that helped to ensure those national security concerns would be mitigated, while still allowing the deal to occur. The changes made to the deal were that “the companies [would]…keep the businesses under the management of UK nationals [and] under the control of UK boards” (DMA 2005). Additionally, “the UK government [was provided] with ‘golden-share’-esque guarantees that the businesses cannot be re-sold by Finmeccanica without its approval” (DMA 2005). Such agreements and remedies provide clear examples of how bounded intervention may be undertaken even by states with the most open of investment regimes.

Over past decades, the UK has prided itself on its openness to FDI, and only minimal evidence exists of unbounded interventions on the part of the UK government during the time period covered by the cases in this book (2001–07). Periodic public debates over the UK's openness to FDI have, however, coincided with unpopular potential and completed foreign takeovers of large UK companies. In 2006, a potential bid for the UK gas company Centrica by the Russian company Gazprom raised concerns over energy security, but the UK Prime Minister at the time reportedly “ruled out any possibility that UK ministers might actively seek to block” such a bid outright (Blitz & Wagstyl Reference Blitz and Wagstyl2006; Seely Reference Seely2016, 16) The 2010 takeover of the beloved UK chocolate company Cadbury by the US food company Kraft resulted in a vigorous public debate over foreign takeovers, led some Members of Parliament to call for the reintroduction of a public interest test for foreign investment, and resulted in some procedural modifications to the UK Takeover Code (Seely Reference Seely2016, 16–26). And, “in May 2014, debate on the public interest test was rekindled by the plans of US pharmaceuticals company Pfizer to make a bid for the UK company AstraZeneca,” due to fears over the impact it could have on the UK science and research base (Seely Reference Seely2016, 30).

Shortly after the British public voted to leave the EU by referendum in June 2016, the soon-to-be Prime Minister Theresa May indicated that under her leadership the UK government would re-examine its foreign investment review system and look into the reintroduction of a broader public interest test that takes into account a wider range of factors than those specified in the 2002 Enterprise Act. Specifically referencing Cadbury and AstraZeneca in a speech on July 11, 2016, while running for leadership of the Conservative party, May said that

a proper industrial strategy wouldn't automatically stop the sale of British firms to foreign ones, but it should be capable of stepping in to defend a sector that is as important as pharmaceuticals is to Britain.30

Yet, in September 2016, the UK government approved the Hinkley Point C nuclear power plant project, with significant investment from China and the French company EDF, after examining the national security implications of the foreign investment. Though this is a greenfield investment, and not a foreign takeover of the type examined in this book, it is notable for two reasons. First, the investment was mitigated through actions to ensure that EDF's controlling interest in the project could not be sold in the future without UK government approval, and the government also announced that it would take a golden share in future nuclear projects to make sure they could not be sold without approval (UK BEIS 2016). Second, as regards the national security review process for all foreign investment, including foreign takeovers, the government announced that:

There will be reforms to the Government's approach to the ownership and control of critical infrastructure to ensure that the full implications of foreign ownership are scrutinised for the purposes of national security. This will include a review of the public interest regime in the Enterprise Act 2002 and the introduction of a cross-cutting national security requirement for continuing Government approval of the ownership and control of critical infrastructure.

Changes to the national security review process, or the adoption of a broader public interest test for foreign investment in the UK, have not been made at the time of writing. Though, in a January 2017 interview, Prime Minister May said that the UK would “in due course…come up with some proposals” regarding the foreign takeover review process, and indicated that the focus would be on “national security and critical infrastructure,” without referencing a public interest test (Parker Reference Parker2017). It will be interesting to watch developments in this area. The introduction of a wider public interest test, to place conditions or block deals on the basis of issues like domestic job retention, is beyond the subject matter of this book. Other potential changes to the national security review process, however, such as the adoption of a broader understanding of national security that includes sectors like critical infrastructure, could bring the UK review process in line with that of countries like the US, and provide the UK with a more comprehensive approach to ensuring the protection of strategic assets through both bounded and unbounded intervention.

Summary

Differences exist in national approaches to the type of restricted intervention we associate with bounded balancing. The process for the review of cross-border M&A is more highly institutionalized among the Western advanced industrial states, which partially explains why we are more likely to see bounded intervention among the allies of the Western security communities. This is significant because higher levels of institutionalization allow allies to find alternative solutions to national security concerns, making it unnecessary for them to resort to other means, such as blocking a deal or throwing up such overwhelming opposition that the proposed acquirer voluntarily withdraws from the process. Low levels of institutionalization in states such as Russia and China – aside from the more closed natures of their markets, which pose a higher risk for investors – may also contribute to the low levels of cross-border deals in those states, especially in strategic sectors. This means we have even fewer examples of bounded intervention in these countries than we might otherwise expect.

Motivations for Bounded Intervention

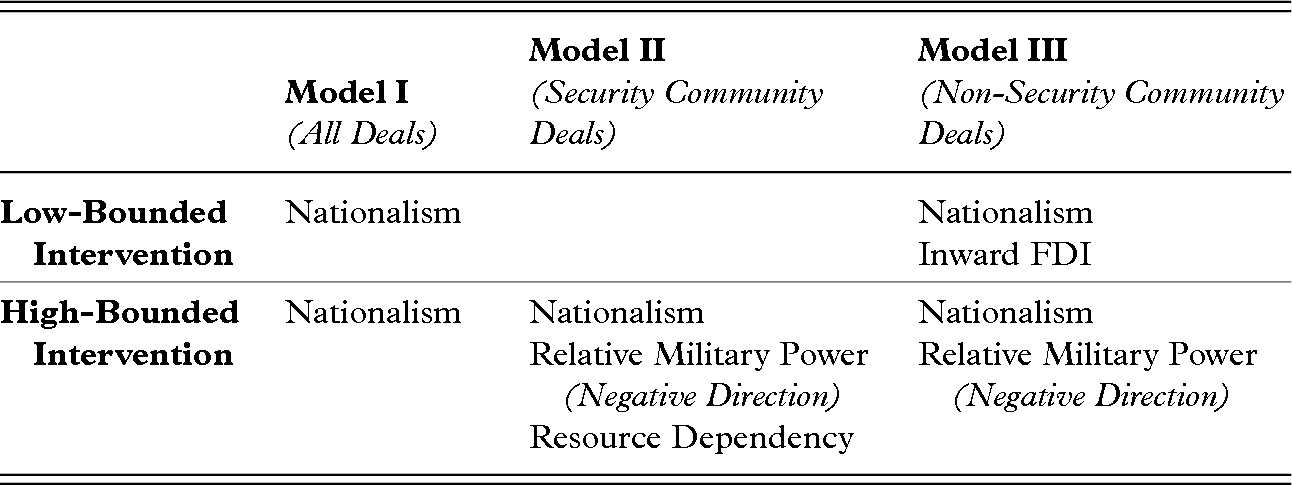

As with unbounded intervention, bounded intervention tends to be motivated by economic nationalism and/or geopolitical competition. The findings in Chapter 2 indicate that the relative importance of these factors varies depending on the subset of cases under examination (Figure 29).

| Model I (All Deals) | Model II (Security Community Deals) | Model III(Non-Security Community Deals) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Bounded Intervention | Nationalism | Nationalism | |

| Inward FDI | |||

| High-Bounded Intervention | Nationalism | Nationalism | Nationalism |

| Relative Military Power (Negative Direction) | Relative Military Power (Negative Direction) | ||

| Resource Dependency |

Figure 29 Bounded intervention: significant motivating factors

Generally, the variable associated with a significant increase in the likelihood of bounded intervention across all cases (MNLM I) is nationalism. As suggested previously, this finding might indicate that higher levels of economic nationalism in state A could also lead a state to protect its national interests through such measures. The analysis of the case studies that follow should help to demonstrate the accuracy of the assumption that economic nationalism is likely to play at least some role in a government's decision to employ bounded intervention.

When the population of cases was reduced to those that took place within the security community context (MNLM II), the significance of those factors representing geopolitical competition became apparent. As noted earlier, the probability of high-bounded intervention significantly increases when state A has higher levels of nationalism, resource dependency, and relative power.31 Interestingly, relative military power is shown to be significant in the negative direction, which may indicate that under certain conditions state A might feel more comfortable imposing modifications to foreign takeovers when it is in an advantaged power position versus state B. Put simply, state A may not feel that it is necessary to use unbounded intervention to solve its security concerns when conditions allow for a solution to those problems through a more restricted form of intervention, which in turn helps to minimize political fallout from its actions. As will be demonstrated in the examination of the Lenovo case, this may remain true even when the acquiring state is a rising power.

In the subset of cases that occurred outside of the security community context (MNLM III), geopolitical factors again show their importance alongside nationalism. The statistical results show that low-bounded intervention was significantly more likely when state A had high levels of nationalism and inward FDI. The fact that IFDI is an indicator of the relative economic power positions of states A and B demonstrates that the concern over the relative geopolitical position of those states plays an important role in determining how state A will handle a foreign takeover that hails from outside of its security community. The results also show that high-bounded intervention was more probable in this subset of cases when state A had high levels of nationalism and relative military power. Military power is again significant in the negative direction, for reasons already explained.

It is evident that nationalism and geopolitical competition increase the likelihood of the restricted form of intervention identified here as “bounded intervention.” As nationalism is used as a proxy for economic nationalism in the quantitative testing, the case studies that follow provide another opportunity to demonstrate the validity of this assumption and the importance of the role played by economic nationalism. The case studies also help to further refine our understanding of the role played by geopolitical competition in motivating this type of intervention. They focus on high-bounded intervention cases, which provide both a tougher test of the hypotheses and a greater opportunity to study the dynamics behind them in detail. Low-bounded interventions, such as those discussed earlier, do not provide the same opportunity to highlight these dynamics due to their more “routine” nature, as states are usually addressing more minor national security issues in such instances.

Furthermore, the case studies in this chapter elucidate the general conditions under which a state might feel more comfortable engaging in bounded, rather than unbounded, intervention. Bounded intervention is more common than unbounded intervention, with the former representing 29%, and the latter only 8%, of the total cases in the database. This may be because allowing foreign takeovers to be completed in modified form is even less likely than unbounded intervention to disrupt trade relationships or produce antagonism between the countries involved. In other words, it best accomplishes the goal of non-military internal balancing: to balance power without necessarily disrupting the greater meta-relationship at stake between the two countries.

Case 6: Alcatel/Lucent

The Context

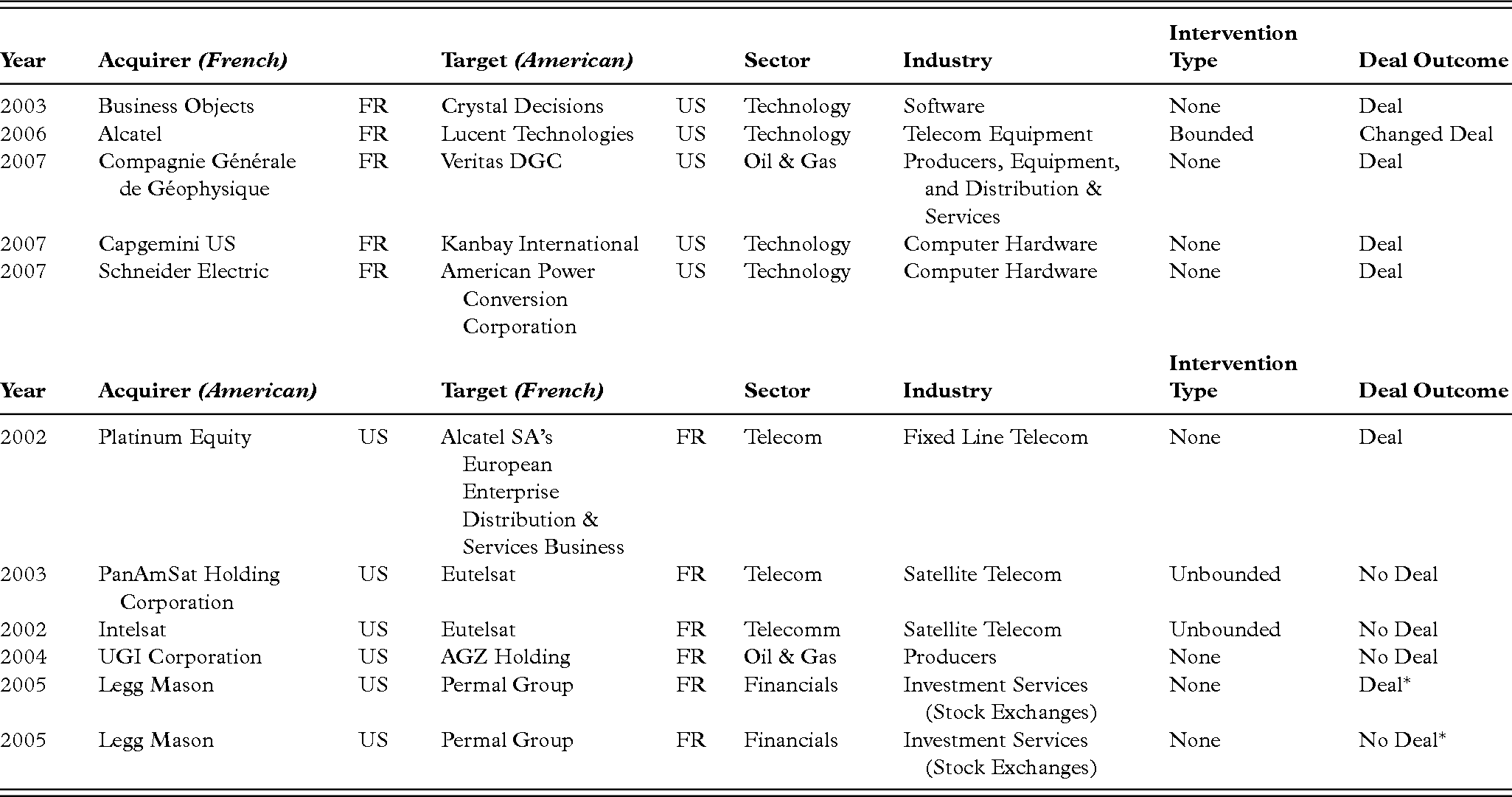

Before delving into the Alcatel/Lucent case, it is important to understand where it stands in the context of the broader M&A market. This particular case involves a French company acquiring a US company in the telecommunications equipment manufacturing industry, which is part of the larger technology sector. Within the parameters of the database created for this investigation, sixty-eight US companies were targeted for foreign acquisition, and only seven of these deals occurred within this particular industry (see Figure 30). Of those, only one involved an acquirer from a country that the Correlates of War project does not classify as a member of the same security community as the US,32 and that country was Sweden, which – though not a member of NATO – remains a very close NATO partner with significant economic, political, and cultural ties. This suggests that in the US, a foreign takeover in this industry is usually more likely to see successful completion when the acquiring company hails from a state with a close relationship to Washington.

| Year | Acquirer (French) | Target (American) | Sector | Industry | Intervention Type | Deal Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | Business Objects | FR | Crystal Decisions | US | Technology | Software | None | Deal |

| 2006 | Alcatel | FR | Lucent Technologies | US | Technology | Telecom Equipment | Bounded | Changed Deal |

| 2007 | Compagnie Générale de Géophysique | FR | Veritas DGC | US | Oil & Gas | Producers, Equipment, and Distribution & Services | None | Deal |

| 2007 | Capgemini US | FR | Kanbay International | US | Technology | Computer Hardware | None | Deal |

| 2007 | Schneider Electric | FR | American Power Conversion Corporation | US | Technology | Computer Hardware | None | Deal |

| Year | Acquirer (American) | Target (French) | Sector | Industry | Intervention Type | Deal Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Platinum Equity | US | Alcatel SA's European Enterprise Distribution & Services Business | FR | Telecom | Fixed Line Telecom | None | Deal |

| 2003 | PanAmSat Holding Corporation | US | Eutelsat | FR | Telecom | Satellite Telecom | Unbounded | No Deal |

| 2002 | Intelsat | US | Eutelsat | FR | Telecomm | Satellite Telecom | Unbounded | No Deal |

| 2004 | UGI Corporation | US | AGZ Holding | FR | Oil & Gas | Producers | None | No Deal |

| 2005 | Legg Mason | US | Permal Group | FR | Financials | Investment Services (Stock Exchanges) | None | Deal* |

| 2005 | Legg Mason | US | Permal Group | FR | Financials | Investment Services (Stock Exchanges) | None | No Deal* |

* In the first deal, Legg Mason acquired 80% of Permal; in the second, it failed to acquire the remaining 20% of the company.

Figure 30 Dataset subset: cross-border deals between the US and France

Furthermore, of those seven cases, the US engaged in some form of intervention in almost every one: bounded intervention in five cases, unbounded intervention in one case, and no intervention in only one case. Significantly, there are indications that the US government would likely have engaged in some form of intervention in the latter instance if the proposed bid had not been dropped before it was formally announced. The suggestion here is that even among allies, this sector is considered so strategically important that deals must at the very least be mitigated in order to ensure the protection of technology related to national security.

The Alcatel/Lucent merger is also the only instance in the dataset in which a French company even tried to buy a US company in this particular industry. In fact, in the dataset as a whole, there are only fifteen cases of a French company buying a foreign company in one of the target countries being examined here, and only five of those cases involved the purchase of a US company. Four of these five cases occurred in the technology sector as a whole, but only the Alcatel/Lucent deal involved the telecommunications hardware industry. This indicates that while takeovers in this subset of the technology sector have been rare, French takeovers of US companies in the technology sector as a whole are not. Figure 30 shows that French takeovers in the rest of the sector met with little resistance, highlighting the need to explain intervention in this case.

Significance

Beyond this market context, a number of factors make the Alcatel/Lucent merger a critical case. First, it is one of the most severe examples of high-bounded intervention. This is because the US government employed a mitigating tool now known as an “evergreen clause,” giving it the ability to reverse the merger at a future date if it becomes dissatisfied with the new entity's adherence to the security agreement it signed as part of the review process. As the first known case in which such a method has ever been used, most market and research analysts consider it critical for understanding the nature of such intervention.

Second, this is also one of the clearest cases of bounded intervention available for study. Detailed knowledge of such cases is quite rare, because the mitigating measures taken by governments are usually classified. Thus, even when we know alterations are made to a deal, we normally only hear the details of those measures if they are voluntarily released by the companies or are leaked to the press. The wealth of information in this case is, therefore, important to study.

Finally, the case is critical to this investigation because it provides a better understanding of the role of bounded intervention within security communities. To understand how, it is necessary to momentarily return to a discussion of the statistical context illustrated in Figure 30. Out of the six attempts by US companies to buy French companies in any sector in the database, only one was successful. This reflects the high level of economic nationalism in France generally, and the geopolitical antagonism toward foreign takeovers by US companies in particular – as illustrated by the infamous PepsiCo/Danone case examined in Chapter 3. Conversely, the Alcatel/Lucent case is the only instance in recent history in which the US intervened when a French company tried to purchase a US technology company. As will be discussed, this is partly because of the timing of the Alcatel/Lucent deal, which came immediately on the heels of the DPW debacle and shortly after the CNOOC case, ensuring that economic nationalism would play a small but important role in the reaction of the US government. Yet, as will be shown, intervention was also triggered by geopolitical concerns. Indeed, the Alcatel/Lucent case is the only one in which a French company targeted a US company that was involved in classified government work and contracts, heightening the geopolitical implications of the deal for the US.

The case is thus critical because it helps to highlight something that the statistical investigation in Chapter 2 could not: that although economic nationalism will tend to play a significant role in cases of bounded intervention within security communities, such an alliance relationship does not necessarily preclude an important role for geopolitical concerns. In the PepsiCo/Danone case, French fear of US hegemony almost mandated such a foreign takeover be blocked. In this case, the US had less to “fear” from France, but France's desire to score a geopolitical coup against the US, its determination at the time to cast the US in a bad diplomatic light, and its disregard for certain US sanctions regimes ensured that the political tensions between the two countries would exacerbate the national security concerns raised by the sensitive nature of Lucent's work.

The Story

On March 24, 2006, rumors of a merger between Alcatel SA of France and Lucent Technologies of the US hit the newswires (Zephyr 2006b). The two companies had discussed a possible merger in 2001, but those talks had failed “over how much control [Alcatel] would have” of a new combined entity (Frost Reference Frost2006). “Since then, however, Alcatel ha[d] grown faster than Lucent, giving it a clear upper hand in merger talks” (Frost Reference Frost2006). Additionally, the sporadic bankruptcy rumors Lucent had faced in 2001 and 2002, as well as the periodic cutbacks and profit warnings it had suffered, made a merger with Alcatel now seem much more appealing (see McKay Reference McKay2006a; Morse Reference Morse2006).

Both Alcatel and Lucent were telecommunications equipment manufacturers in the technology sector.33 Yet, while the majority of their business focused on the private sector, each company held defense contracts with its respective government, and each had divisions dedicated to the development of sensitive technology. Alcatel, for example, owned a stake in two satellite-manufacturing JVs, Alcatel Alenia Space and Telespazio, with Italy's Finmeccanica. Alcatel Alenia worked on sensitive projects such as the first iteration (Giove-A) of the Galileo Satellite (see Alcatel 2006b). Lucent, meanwhile, held a number of contracts with the US DOD that ranged from providing it with “classified technology” to supplying “telecoms equipment for the Iraqi reconstruction project” (MacMillan Reference MacMillan2006). Lucent also owned and operated Bell Laboratories, an entity that for eighty years had conducted classified work for the US government: producing the transistor, the laser, and the touch-tone phone, while pioneering solar cells, cell phones, and the communications satellite (Alcatel-Lucent Reference Alcatel-Lucent2008; Reuters 2006a). Such pedigrees indicated that any deal between Alcatel and Lucent would raise national security concerns for both the US and France.

Not surprisingly, many analysts who felt the deal might make sense economically remained wary that its security implications could lead to failure if not addressed early, adequately, and carefully (see e.g., AFP 2006c; McKay Reference McKay2006b; Morse Reference Morse2006; Wickham Reference Wickham2006). Others believed that, even then, the deal might be blocked (see e.g., MacMillan Reference MacMillan2006). Thus, while it remained only a rumor, analysts had already begun to contemplate the different ways the deal might be mitigated in order to satisfy both Washington and Paris. The most common suggestions and commentary assumed that, at the bare minimum, France would encourage Alcatel to sell its satellite divisions to another French company, such as Thales, and Lucent would need to protect Bell Labs by either divesting it, or creating a subsidiary that would be closed off from foreign influence (see e.g., Butler Reference Butler and Michelson2006; Dow Jones 2006c; McKay Reference McKay2006a; Morse Reference Morse2006). These hurdles were not low, but many market and industry observers believed that, if they were executed well, the merger would not be blocked unless it became “a political football” like the DPW deal (MacMillan Reference MacMillan2006). Indeed, it was unlikely that France would completely block a deal that was largely in its favor, and that was viewed as a triumph for the French tech industry.34 In the end, the lack of French cooperation geopolitically, combined with the need to protect classified materials and the rising protectionist sentiment in the US at that particular time, ensured the US government would at least intervene in a bounded fashion; and extreme politicization of the deal could have resulted in unbounded intervention.

By April 2, 2006, a definitive merger agreement was reached between the two companies valued at US $13.4 billion, giving Alcatel shareholders a 60% stake of the new combined entity and Lucent shareholders 40% (Zephyr 2006b). Because concerns over equality had quashed attempts by the two companies to merge in 2001, a clear effort was made to sell this as a “merger of equals” (MacMillan Reference MacMillan2006). Hence, it was announced immediately that Lucent's CEO Patricia Russo would head the new combined company, and in return its headquarters would remain in Paris, its CFO would come from Alcatel, its COO from Lucent, and the new board of directors would be equally drawn from Alcatel and Lucent's existing board members (AFX 2006a). Yet, despite these overt efforts toward equal partnership, the market generally viewed and treated the deal as a foreign takeover of a US company by a French one (Intereview 2008b). Lucent was clearly the “junior partner” in the merger, and even M&A databases such as Zephyr classify the deal as an acquisition of Lucent by Alcatel (MacMillan Reference MacMillan2006; Morse Reference Morse2006; Zephyr 2006b). Thus, while the details of the French position will still be discussed, Lucent will be treated as the target company for the purpose of this investigation.

Unlike most of the cases examined in the previous two chapters, Alcatel and Lucent sought to address the national security implications of their proposed deal before it was even officially announced.35 In France, Alcatel sought early on to push through a previously discussed arrangement whereby the French defense electronics company Thales would take Alcatel's stake in its satellite JVs in return for a stake in Thales (see TelecomWeb 2006c). This deal would both calm France's worries about sensitive technology being seen by foreign citizens and help the government protect the vulnerable French Thales from a takeover by the European EADS (see Dow Jones 2006d; Financial Times 2006a; TelecomWeb 2006c). In the US, Lucent issued a press release when the proposed merger was announced in order to calm fears over the future security of Bell Labs. The release stated that “the combined company [would] form a separate, independent US subsidiary under Bell Labs…to perform research and development work for the US government that is of a sensitive nature,” and that Bell Labs would not be moved or its leadership changed (Lucent 2006). Lucent also announced it “ha[d] asked three experienced and distinguished members of the national security community to serve on the independent subsidiary's board,…subject to US government approval,” namely former Secretary of Defense William Perry, former NSA Director Lieutenant General Kenneth Minihan, and former Director of Central Intelligence James Woolsey (Lucent 2006). These actions were meant to “black box” Bell Labs from foreign control and influence, allowing only the revenue from its activities to go to the new entity. Such special subsidiaries can alleviate national security concerns, allowing governments, that wish to do so, to mitigate foreign takeovers without having to block them outright. By announcing their willingness to create such a subsidiary early on, Alcatel and Lucent were trying to anticipate the problems their deal might face, and cast their intentions in a positive light. It was likely hoped this would alleviate existing geopolitical tensions between the two countries in order to prevent the kind of unbounded intervention that had been so recently faced by DPW and CNOOC in the US. The companies then “submitted a voluntary notice of the merger to CFIUS in August 2006” (Alcatel 2006a), and were reported to have worked (and cooperated) closely with that same body in order to resolve the US government's concerns (Dow Jones 2006e).

In order to properly understand the US reaction to the Alcatel/Lucent merger, it is necessary to examine the political context in the US at that time. This deal surfaced just after the heavily politicized DPW case, which unleashed a furor of congressional rhetoric about the threat foreign takeovers could potentially pose to national and economic security. Both economic nationalism and national security awareness were therefore abnormally heightened by this time, and were being manifested in a rush of legislation proposed to reform CFIUS and make the foreign takeover review process more stringent.

Not surprisingly, Congressman Duncan Hunter (R-CA), who had been vociferously against the DPW deal, came out early on against the Alcatel/Lucent deal (see AFX 2006b). In a letter to President Bush dated April 28, 2006, Hunter stated:

I have several grave concerns about the potential merger…[that] arise in large part because Lucent Technologies and Bell Labs, a critical component of the parent company Lucent Technologies, conduct a significant amount of highly classified work for the United States government, including the Department of Defense. I am skeptical whether the current CFIUS process could provide adequate, verifiable assurances that such sensitive work will be protected.

Both companies responded directly to Hunter's concerns, reiterating the precautions they had already announced regarding the future of Bell Labs. Yet, it was clear that Hunter no longer believed CFIUS to be an effective review body and was voicing his concerns in order to make CFIUS more accountable.

Another issue raised by Hunter, which the companies, interestingly, did not immediately address, was the fact that the merger “could result in transfers of sensitive technologies or information to several countries with which Alcatel has dealings, including [Myanmar], China, Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Sudan, and Syria” (Inside US Trade 2006a). This is significant for the discussion of geopolitical tensions that follows, because though the US and France are part of the same security community, long-standing tensions over French disrespect for US-led sanctions regimes proved difficult to overcome, making it highly likely the US government would intervene in some way in this case in order to protect the technology involved.

Despite these concerns, Congressman Hunter was largely alone in his desire to block the deal. In other words, his rallying cry for unbounded intervention was not answered in this case, because the French position as a formal ally made bounded intervention both more desirable for the US and more creditable within the international community. Unlike the Check Point/Sourcefire deal, it seemed possible that mitigation could satisfactorily address the geopolitical and security issues raised by this deal, because the critical technology concerned did not represent all of Lucent's business. Hence, it was reported that Hunter's message did not “resonat[e] with many other members of congress” and was not echoed by them (Inside US Trade 2006a). Indeed, “one private sector source” made it clear that Hunter's actions were an attempt “to politicize the CFIUS process,” but “doubted [his actions] would impact a presidential decision on the CFIUS recommendation” regarding this deal “or on the broader debate over how to reform the CFIUS process” in general (Inside US Trade 2006b).36

By mid-September 2006, the Alcatel/Lucent deal had received most of the necessary regulatory approvals. The deal was approved by the boards of directors of both Alcatel and Lucent on April 2, and by the shareholders of both companies on September 7 (Zephyr 2006b). The merger also received anti-trust approval from the US Department of Justice on June 8, and competition clearance from the European Commission on July 24 (Johnson Reference Johnson2006; Zephyr 2006b).

It is clear, however, that the heightened protectionist sentiment post-DPW/P&O, the one-off factor of the CFIUS reform debate that DPW and CNOOC had triggered, and geopolitical tensions with France, did contribute to a more rigorous investigation of the Alcatel/Lucent deal within CFIUS. On October 6, it surfaced that CFIUS would engage in the formal forty-five-day investigation (in addition to the normal thirty-day review) of the proposed merger. In fact, Clay Lowery, the Treasury Assistant Secretary for International Affairs, later testified before Congress in regards to the Alcatel/Lucent review that “CFIUS conducted one of the most rigorous and thorough investigations ever on a transaction before the committee” (Dow Jones 2006e).

These factors motivated the US government to engage in one of the most severe cases of bounded intervention in its history. It was announced on November 14 that CFIUS had concluded its review of the proposed merger, and on November 17 that President Bush had accepted CFIUS’ recommendation to approve the deal, which by then included numerous mitigating changes requested by CFIUS and agreed to by both companies. It is likely that the proactive stance taken by both Alcatel and Lucent toward the mitigation of the US government's national security concerns helped them to navigate this process successfully, as did the fact that “CFIUS ha[d] been in contact with the companies even before the…formal security review process began” (Dow Jones 2006e). By November 30, 2006, the merger was officially completed, and the entity Alcatel-Lucent opened for business under its new moniker the next day.

Yet, it is important to understand that while this deal seemed to the general public to go through without a hitch, the US government actually did engage in one of the clearest and intense examples of bounded intervention of which the details are publically known. For, in addition to the proposed provisions made by the two companies regarding Bell Labs, which were adopted in the final agreement, the US government required Alcatel and Lucent to “enter into two robust and far-reaching agreements designed to ensure the protection of [US] national security”: a “National Security Agreement and a Special Security Agreement” (TR Daily 2006). Though the exact details of these agreements are classified, it is assumed by the market that they covered the provisions made for the protection of Bell Labs and other classified work and contracts held by Lucent.

Furthermore, it was later confirmed that these agreements contained the evergreen clause mentioned earlier, allowing the US government to call for a reversal of the merger at any future date if it felt that the agreements were not being properly implemented. According to private-sector sources, such a clause had never been used before in the US, and many viewed it as highly detrimental because it might prohibit future FDI (Interview 2007). Thus, on December 5, 2006, the Business Roundtable, the Financial Services Forum, the Organization for International Investment, and the US Chamber of Commerce wrote to then Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson to “express concern over [the] so-called ‘evergreen’…condition…attached to CFIUS’ approval of the Alcatel/Lucent merger” (Inside US Trade 2006c). They pointed out that the serious nature of the inclusion of the evergreen clause lay in the fact that