The Theoretical Context

Bretton Woods marked the beginning of a liberal economic order, establishing a global system founded on free-market principles. Its purpose was not only to deepen economic interdependence in order to help the West and the world realize the absolute gains that attend free trade, but also – through the deepening of such ties – to lower the likelihood of future conflict within the international system. The order was intended to be durable, institutionalizing the economic and political values of the West in a manner that would outlast the eventual decline of the country that had thus far forcibly defended it – the US (see Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2001).

Over the past decade, however, there has been a notable trend in state behavior that one might not expect in this context. For, though cross-border M&A has proven to be one of the foundation stones upon which the liberal economic order rests, there has been a surge of state intervention into this type of financial transaction on national security grounds. Significantly, this behavior is not unique to any one country or group of countries; it is not a “Western” or a “non-Western” phenomenon. Yet, many observers find it surprising that states are intervening against “foreign” takeovers originating from within their own security communities – communities founded not only on the historical sense of “we-ness” that emerges from exceptionally close long-standing alliances, but which are also often rooted in a commitment to economic liberalization and, in the case of the EU, integration.

The purpose of this book has been to explain this simple puzzle: to understand why states are engaging in such behavior not only against their strategic and military competitors, but against their closest allies as well. Because existing theories cannot fully explain this behavior, I present a new theory that builds on the insights of structural and neoclassical realism. Beginning from the realist assumption that states living in anarchy will compete for power and seek to balance challenges and threats to their relative power through either internal or external means in order to ensure their own survival, I also recognize that this struggle for power among states will not always be played out in the military or diplomatic realms. For, though nuclear weapons have decreased the likelihood of a major power hot war, the competition for scarce resources and technology is arguably on the rise. Thus, one can expect that conflict will increasingly occur in the economic realm, and that some states will try to take advantage of the interdependent relationships that arise from economic globalization through FDI.1

Some states will use the market to try to gain economic and military power through companies they control. China has long been known to acquire (through companies it influences or owns) foreign companies in order to gain control of and/or access to their technology and resources, or for the simple purpose of conducting espionage (Graham & Marchick Reference Graham and Marchick2006, 100–17). Russia has made no secret of its desire to use the M&A market as a way to gain access to, and the right to distribute, natural resources abroad. Additionally, as sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) increase in terms of their power, wealth, and scope of activity, it raises concerns that some SWFs may not always be subject to the same market-based motivations as other financial actors (Lenihan Reference Lenihan2014). As a result, states are increasingly vigilant in their efforts to ensure that cross-border M&A transactions do not make them dependent on other states, or pose a threat to their position in the international system.

This is not to imply that the insights of neoliberal institutionalists or liberal economists are wrong. States clearly recognize the value of the absolute gains that free trade and international cooperation can bring, as demonstrated by their efforts to reduce barriers to global trade through the WTO. Yet, there is a difference between agreeing to trade goods and services without the imposition of tariffs and the willingness to allow, for example, a domestic company that makes your air force's fighter jets to be taken over by a foreign company.

It is for this very reason that states have refused to give up the right to block cross-border mergers or acquisitions that they believe pose a threat to their national security, even if the result of such transactions would be otherwise beneficial for their economy. As a result, and because governments reserve the right to identify the nature of such threats on their own, states have been largely unable, or unwilling, to agree to a multilateral treaty governing cross-border M&A, making this one of the last remaining arenas in which such economic power competition and conflict can play out without violating international law.

Non-Military Internal Balancing

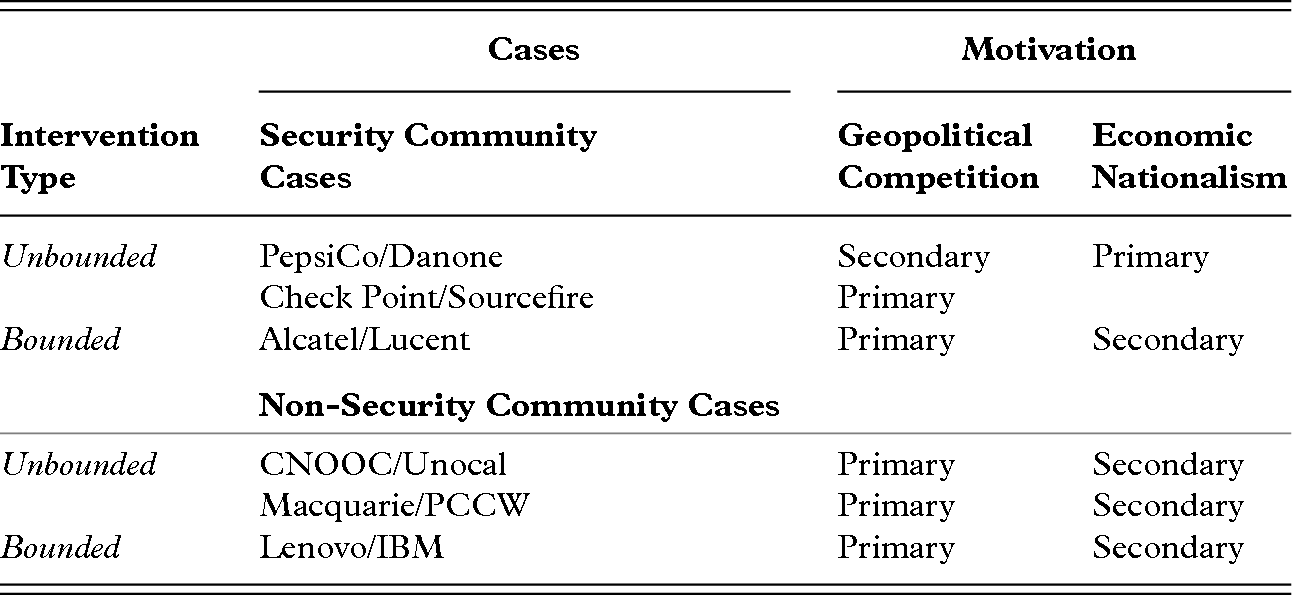

This study has demonstrated that governments will intervene in foreign takeovers that they believe challenge or threaten their relative power, using such intervention as a tool of non-military internal balancing. This intervention will either be unbounded (direct action aiming to block the deal), bounded (direct action to mitigate the negative effects of the deal), or internal (encouraging domestic-based actions and outcomes that obviate the need for direct intervention into a specified deal). The exact form intervention takes, and the motivations behind it, vary with the nature of the relationship between the countries involved and the exact nature of the threat posed by the transaction in question.

This work has also shown that geopolitical competition and economic nationalism are the primary motivating factors behind direct government intervention into foreign takeovers of companies in national security industries. This argument assumes that, in each case of intervention, an element of the specified takeover can be legitimately construed as posing a national security risk, before these factors come into play. Alternative explanations of state behavior were also controlled for and examined. Statistical analysis confirmed that the presence of geopolitical competition and/or economic nationalism in a particular country increases the likelihood that it will engage in either unbounded or bounded intervention. Neither interest group presence nor economic competition proved to be generally significant, demonstrating that these factors do not provide an adequate alternative explanation for such action.

These findings were substantiated in the case studies (see Figure 34 for a summary of the direct intervention cases examined in Chapters 3–5). Both geopolitical competition and economic nationalism proved to be the motivating factors behind state action in both cases of bounded intervention and in three of the five unbounded intervention cases examined; and in one case of unbounded intervention, geopolitical concerns alone proved relevant. Even the outlier unbounded intervention case (DPW/P&O) offered some support for the primary hypothesis. In that case, an unusually high level of politicization of the deal allowed two values of economic nationalism (one high, one low), and two alternative understandings of the geopolitical relationship involved, to emerge within the same state. Certain lawmakers were therefore able to believably couch their concerns – whether justified or not – in terms of national and economic security, and the US-related aspects of the transaction were blocked. The hypothesis also held in both cases of non-intervention. In addition, even though the hypothesis was formulated to explain direct forms of intervention (and further analysis is thus necessary), the final case examined in Chapter 6 indicated that the hypothesis may even help to explain cases of internal intervention.

| Intervention Type | Cases | Motivation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Security Community Cases | Geopolitical Competition | Economic Nationalism | |

| Unbounded | PepsiCo/Danone | Secondary | Primary |

| Check Point/Sourcefire | Primary | ||

| Bounded | Alcatel/Lucent | Primary | Secondary |

| Non-Security Community Cases | |||

| Unbounded | CNOOC/Unocal | Primary | Secondary |

| Macquarie/PCCW | Primary | Secondary | |

| Bounded | Lenovo/IBM | Primary | Secondary |

Figure 34 Case study findings: unbounded and bounded intervention

For the theory to hold, it was also important to show that intervention type actually affects deal outcomes. The statistical data confirmed that this could be said to be true with 99.9% confidence, and that as the degree of government intervention increases, so too do the chances of a deal being mitigated or blocked. As predicted, each case study of an unbounded intervention resulted in a no deal outcome, and both cases of bounded intervention led to mitigated deals. Additionally, in both cases of non-intervention, where the state did not believe the deal to raise any national security concerns, the transactions proceeded unaffected as expected, with one completed and the other leading to a management buy-out.

Significance

The Puzzle Revisited

The answer to the puzzle seems to lie in a few discoveries. First, it is important to recognize that intervention within the security community context will only rarely take the unbounded form. Across all cases, intervention will most often take the bounded form. For the total population of cases examined in this study, the bounded intervention rate was 29%, compared to a rate of only 8% for unbounded interventions. Significantly, when these numbers were broken down, it was confirmed that the rate of unbounded intervention is even lower in security communities (at 7%) than it is outside them (where the rate is 12%).

I found that this lower rate of unbounded interventions within security communities might be explained by a number of factors. One is that the review process through which cross-border deals are mitigated is often more highly institutionalized in the countries that are coded here as being members of a strong security community, which may make bounded intervention more effective and reliable in the eyes of those states. A more fundamental reason for the lower level of unbounded intervention within security communities, however, is simply that within that context, such drastic measures of state action are rarely considered necessary.

This brings us to the second finding. Economic nationalism will, for the most part, play a greater role than geopolitical competition in motivating unbounded intervention within the security community context. This is because the geopolitical tensions within such relationships are usually very low, and therefore cross-border transactions within those contexts are less likely to pose intractable national security threats. In other words, any national security issue that originates from geopolitical concerns in this situation can usually be resolved through mitigation of the deal in question. Geopolitical tensions or concerns will only rarely be so acute within a security community context that they alone motivate unbounded intervention. Instead, high levels of economic nationalism will normally be the primary motivator of unbounded intervention in this situation.

However, it is also important to understand that geopolitical competition can still play a role in explaining intervention within the security community context, under certain circumstances. The statistical analysis demonstrated that geopolitical competition would significantly increase the likelihood of bounded intervention within security communities. This finding was supported by the Alcatel/Lucent case, where geostrategically based national security concerns were shown to be the primary motivator of bounded intervention. Furthermore, intractable geopolitical competition and geostrategic concerns, of a nature that cannot be resolved through bounded intervention, can still occur within security communities. In such situations, these concerns can be the secondary, primary, and/or sole reason for unbounded intervention within a security community. As mentioned earlier, this is likely to occur in cases such as Check Point/Sourcefire, where the nature of both the concern and the transaction makes unbounded intervention the only option for achieving non-military internal balancing and protecting national security, despite the close relationship of the countries involved. An unusually high level of economic nationalism may also exacerbate an existing geopolitical tension within a security community, as occurred in the PepsiCo/Danone case.

Thus, the answer to the puzzle becomes clear. The puzzle asked why states would engage in ostensibly protectionist behavior not only against their strategic and military competitors, but also against members of the same security community founded, in part, on economic liberalism. It has been argued here that these acts of intervention can be more clearly understood once they are identified as a tool of non-military internal balancing. This form of internal balancing is focused on immediate challenges to long-term military and/or economic power; challenges that can come in the form of a foreign takeover initiated from non-allied and allied countries alike. Yet, the tool of balancing used – in this case, government intervention into those foreign takeovers – can be tailored to respond to the difference in the level of threat. It was found that the most serious form of intervention, unbounded intervention, is only rarely used within security communities. The ability of states to employ a bounded form of intervention, in an institutionalized and routine manner, helps explain how intervention is possible within the security community context. The fact that such internal balancing as a whole is non-military in nature explains why even unbounded intervention has become possible and permissible within a security community. The end goal of such balancing is to protect and preserve power without disrupting the greater meta-relationship at stake between the two countries involved. Hence, even unbounded intervention – though generally more intense and serious – is unlikely to create any long-term rift within a security community relationship on its own.

Even within the EU – a security community founded on economic liberalism and integration – states pursue this strategy of internal balancing to gain (especially economic) power and position within the context of that greater relationship. That government intervention into foreign takeovers, undertaken for the preservation of national security, is seen as a right of the state, and is not prohibited under international law, makes it in many ways one of the last areas in which states can intervene in the international market in order to preserve their economic and military power. Considered in such a light, it is not surprising that states within close alliance relationships might use this form of balancing, perhaps either to balance a state whose rising power they think could prove destabilizing to the alliance over the long term, or to preserve or gain a leadership position for themselves within that alliance. The interventionist behavior of Germany and France, and even Spain and Italy, provides an excellent example of this strategy being employed within the EU. Events such as the UK's 2016 referendum decision to leave the EU highlight the tensions that can exist beneath the surface of even the closest of alliances.

Where intervention becomes truly shortsighted is when it is fundamentally misused and becomes a case of over- or inappropriate balancing, as occurred in the DPW/P&O case. Such cases, where intervention is almost universally perceived as unwarranted outside the target state, are especially impolitic and imprudent because they are either (1) seen as a case of pure economic protectionism with no true national security foundation, or (2) viewed as being antagonistic to the sending state. In either case, the goal of non-military balancing is lost, and there is the potential for a disruption in the meta-relationship between the states involved and, as discussed in the next section, for a negative impact on the economic system as a whole.

Conflict, Competition, Economic Interdependence, and Systemic Change

The theory and findings presented in this book should also shed additional light on the relationship between economic interdependence and conflict. As discussed at the beginning of this work, Waltz (Reference Waltz1993) suggests that realists should expect conflict – especially economic conflict – to potentially increase with interdependence. Even Keohane and Nye (Reference Keohane and Nye2001) recognize that “conflict will take new forms, and may even increase” as interdependence deepens over time. Yet, both of the theoretical approaches represented by these authors (realism and complex interdependence theory, respectively) are underspecified concerning the intensity and form such conflict is likely to take.

The theory presented in this book shows the value of reconciling the insights from these two approaches. For, competition does take an increasingly economic form, but – especially within security communities that are also highly economically interdependent – such competition must also take a novel form. It might be that as interdependence increases within the EU, for example, traditional forms of economic conflict (such as tariffs) disappear, and new ones (such as intervention into foreign takeovers) rise to take their place. This may be especially true when these new tools have the ability to appear less confrontational and sweeping. In fact, it might be that states are not only finding new ways to deal with the competition for economic power, both within and outside such interdependent relationships, but also that the progression of these relationships necessitates this evolution. Thus, government intervention of the type examined here is, in many cases, truly vital to the protection of national security because of the more open environment for cross-border M&A.

This can be viewed positively, as it demonstrates an attempt by states to balance power shifts internally, and in a non-military fashion, in order to avoid more serious forms of conflict further down the line. Certainly, the findings did confirm that, for all cases of intervention in the database, with the exception of the outlier case, a legitimate state-defined national security concern was attached to the affected transaction. The findings also demonstrate a preference among states for dealing with such national security concerns through deal mitigation (bounded intervention) where possible, rather than through continual attempts to block disadvantageous deals (unbounded intervention).

The evidence presented in this book thus confirms the need for theorists to have a more holistic understanding of power and national security. Conflict and competition do not disappear when the likelihood of major power war is relatively low. Instead, competition among great powers (and even second- and third-order powers) may simply take a non-military form. This scenario illustrates the value of recognizing that other forms of power become important for determining great power “rank.” This does not just mean recognizing the usefulness and necessity of social power and soft power, it also means an acknowledgment of the increasing relevance of economic power. This is particularly true if one believes that one of the next major sources of conflict in the international system will be the scarcity of vital natural resources (NIC 2008, 63), or control over the next big technological breakthrough.2 Such competition is likely to be played out in the economic sector in the future. Indeed, cross-border M&A is a front line in the battlefield over some vital aspects of economic and military power. Intervention into such transactions takes on an important role as a form of internal balancing, for the very reason that some states will attempt to use foreign takeovers as a way to take advantage of interdependent relationships and gain control over resources, technology, information, critical infrastructure, and other strategic sectors of the economy.

For instance, recent evidence shows that states are using foreign investment into the US to achieve such goals, and to increase their power relative to that country. In three out of its last four annual reports to Congress, CFIUS disclosed the US intelligence community's assessment that “there may be,” or that “there is likely,” such “a coordinated strategy among one or more foreign governments or companies to acquire US companies involved in [the] research, development, or production of critical technologies for which the United States is a leading producer” (US DOT 2012, 23, 2015, 26, 2016a, 29). CFIUS has regularly pointed out that other “coordinated strategies may go unobserved due to limitations on intelligence collection, or may be hidden or misconstrued because of foreign denial and deception activities” (see US DOT 2009, 28, 2010, 19, 2011, 25–6, 2012, 23). Moreover, credible evidence of industrial espionage by foreign governments seeking access to critical US technology was found in each year since reporting began in 2008 (see US DOT 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016a; US NCIX 2006).3

While the unclassified versions of these reports do not specify which foreign governments or companies are suspected of such activities, many countries have, for example, shown concern over certain types of foreign investment from some Chinese companies. These concerns are not surprising given stated Chinese policy, which makes no secret of a government-led industrial strategy that involves using foreign investment to the state's advantage. Within the wider context of its “going out” strategy,4 the Chinese government openly encourages outward foreign investment that might help it “mitigate the domestic shortage of natural resources” or gain access to “internationally advanced technologies” (UNCTAD 2006, 210). More to the point, such investments are often state-directed or coordinated by companies that, if they are not state-owned, frequently have government-appointed or affiliated executives (Salidjanova Reference Salidjanova2011, 4). China also often supports these investments by offering incentives to companies that make them, or by providing cash and credit from state banks, SOEs, and SWFs to help finance these deals (Lenihan Reference Lenihan2014, 242–5; UNCTAD 2006, 210).

As discussed throughout this book, countries like the US, Australia, Canada, and Germany have therefore blocked or mitigated those Chinese investments that appear to pose a risk to national security, balancing against specific targeted threats to relative power. Concerns have been raised over investments made by two Chinese telecoms firms in particular, Huawei and ZTE, because of their suspected links to the Chinese government, history of attempted purchases of sensitive companies, and lack of transparency (US House 2012). A 2012 investigative report to the US House Intelligence Committee determined, for example, that the US “must block” foreign investment involving these companies because of the “threat” they pose “to US national security interests,” and that the US “should view with suspicion the continued penetration of [its] telecommunications market by Chinese telecommunications companies” (US House 2012, vi). Similarly, a 2013 report by the Chair of the UK Parliament's Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) raised national security concerns over the involvement of Huawei in that country's critical telecommunications infrastructure (ISC 2013). Beyond these specific companies, the national security risks raised by other proposed Chinese investments have ranged from the proximity of potential acquisitions to sensitive military installations, to the information, technology, or resources possessed by the target companies involved. For instance, in October 2016, the German government withdrew its initial approval for the takeover of the German chipmaker Aixtron by the Fujian Grand Chip Investment Fund because Aixtron “owns technologies relevant to national security” and Grand Chip's consortium of investors included those with suspected ties to the Chinese government (Chazan & Wagstyl Reference Chazan and Wagstyl2016). As discussed in the Introduction, President Obama notably vetoed Grand Chip's proposed acquisition of the US business of Aixtron by Grand Chip just two months later, in December 2016, over similar national security concerns (see Obama Reference Obama2016; US DOT 2016b). And less than a year later, President Trump vetoed the purchase of Lattice Semiconductor by an acquirer determined to be supported and funded by the Chinese government, on comparable grounds (see US DOT 2017). In late 2016, it was reported that Germany is considering strengthening its own legal and regulatory regime for the review of foreign investment affecting national security, and is also “pushing for new EU rules that would allow member states to protect companies working in strategic sectors from Chinese approaches, especially when the acquirers are linked to the Chinese state” (Chazan & Wagstyl Reference Chazan and Wagstyl2016). Similarly, the UK revealed in 2016 that it is considering changing its system for screening and assessing foreign investment following a national debate over the national security implications of Chinese investment in the UK's Hinkley Point C nuclear power project, even though that investment was eventually approved.5

All of this should be understood within a wider context, in which the global distribution of economic power is undergoing a fundamental shift. The US has had the largest economy of any single country in the world – by a wide margin – since the end of the Cold War (as measured by GDP in current USD), being roughly similar in size to that of Europe.6 But there has been a dramatic shift in the fortunes of the developing world, and especially of the BRIC countries of Brazil, Russia, India, and China, in the 21st century. While the global financial crisis and the collapse in commodity prices dampened the growth trajectory of many of the BRICs, and Russia's growth has faced the additional drag of the economic sanctions imposed on it in 2014, China remains on course to displace the US as the world's biggest economy by 2050.7 Though China faces its own internal economic challenges,8 and GDP is only one very basic measure of economic power,9 it is nevertheless a powerful indicator of China's potential rise in relative economic power vis-à-vis the US, Europe, and Russia. At the same time, China's increasing activity in the South China Sea in the 2010s, and Russia's engagement in Ukraine and Syria in the same period, show a willingness by these countries to test boundaries in the military sphere. Though long-term changes in military power are harder to predict, it will be difficult (without groundbreaking innovation or technological change in the West) for the US and Europe to maintain the positions of economic power they currently enjoy given (among other factors) the maturity of their economies and the demographics of their populations.

The looming possibility of systemic change implied by these trends only intensifies the need to understand the types of competition and balancing discussed in this book. For, as the US is faced with the possible loss of its primacy, the world may be moving toward a system that is truly multipolar. This work began from the premise, after Nye, that the system was unipolar in the military realm and multipolar in the economic one. But it is quite possible to envision that we are on the cusp of systemic change – and that the system will be multipolar in both realms in the not too distant future. This change should not affect the theory of non-military balancing posited here, which was designed to hold regardless of the polarity of the international system. Such a scenario may, however, lead to an increase in the type of competition and balancing examined in this study. Thus, recognizing the importance of the economic component of power, the tools of non-military balancing available to states, and when and why such balancing might occur only becomes more important.

Resurgent Economic Nationalism and Non-Military Internal Balancing

The mid-2010s saw a rise in nationalism in a number of advanced industrial and industrializing states. To name but a few, these have included Japan, Russia, India, and China in the East, and the US, UK, France, and Hungary in the West. Many of the nationalist movements in these countries have been linked to a resurgent economic nationalism, often in combination with one of the many variants of populism.10 Foreign and economic policy in China under President Xi Jinping, for example, has focused on “realizing the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” (Wang Reference Wang2016). In Japan, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's economic program, often referred to as Abenomics, has been likened to “economic populism” (see Stewart & Wasserstrom Reference Stewart and Wasserstrom2016). In the US, the election of President Trump marked a victory for a populist movement notable for its emphasis on nativism, as well as anti-free trade and anti-globalization sentiments. The UK's decision to leave the EU, though the result of an array of political factors, was partially attributable to anti-immigration sentiment and growing feelings of economic nationalism within Great Britain. Nationalist and populist movements in France, Germany, Hungary, and the Netherlands evidence similar themes. It is unclear the degree of success these movements will ultimately achieve, or how long they will last, but it is clear that they will have an impact on geopolitics, and that the rise in economic nationalism associated with them will have an impact on non-military internal balancing.

The theory presented in this book suggests that when a particular merger or acquisition is recognized to pose a legitimate potential national security risk, a higher level of economic nationalism in the target state contributes to a greater likelihood that it will intervene in that particular transaction under certain circumstances. Cumulatively, higher levels of economic nationalism within the international system could therefore trigger a higher level of, albeit legitimate, intervention into cross-border M&A globally. In particular, we might expect states to intervene in foreign takeovers that originate from within their own security communities to a greater extent than we might otherwise expect without the heightened presence of economic nationalism. This is a situation for which both the public and the private sectors may need to prepare, but which will not necessarily lead to a chilling economic or political effect on the international system.

The danger would be if economic nationalism spills over, under populist leadership and amidst nationalist fervor, to lead states to abuse or misuse this tool of non-military internal balancing. In such a scenario, it is possible to envisage a state blocking or vetoing a transaction on national security grounds when the national security risks involved could have, instead, been mitigated by simply modifying the transaction. In other words: in such a scenario, it is possible to imagine states overbalancing by employing unbounded balancing where bounded balancing would have sufficed. Worse still would be a state intervening in a foreign takeover when there are no justifiable national security concerns present, but still citing national security as the reason for intervention. Both actions would be examples of overbalancing and miscalculation that could result in costly economic, political, and diplomatic outcomes for the states involved, or for the international system as a whole, if such behavior were to become widespread.

The systemic effects of such behavior could be magnified if it were to originate in the US, the leader of the liberal economic order from its inception at Bretton Woods, or the EU, which has thus far been a staunch ally and supporter of that order. This is not to say that the liberal economic order would not survive – the order is highly institutionalized and durable, and therefore likely to survive this and other challenges (see Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2001; Nye Reference Ye2016). Such behavior on the part of the leaders of the liberal economic order could, however, be enough to stay or slow the pace of globalization that we might have otherwise expected to see under its umbrella.

Globalization and Government Intervention into Foreign Takeovers

It is vital to realize the impact that this tool of non-military internal balancing could potentially have on the forward progress of globalization if it is misused. Cross-border M&A has become one of the main engines of globalization, and that position should not necessarily be threatened when non-military internal balancing of the type studied here is used appropriately. Yet, unnecessary or overbalancing, of the type witnessed in the DPW/P&O case, can carry a heavy cost for the states involved, and if the mistake is repeated by a widespread number of states, the impact can be systemic.

The misapplication of this intervention tool in an individual case means that the goals of non-military internal balancing will not be met, and, therefore, that it could potentially lead to a strain on the economic, or worse the diplomatic, relationship between the countries involved. For, such action is likely to be viewed as either antagonistic or unnecessarily protectionist. If a country gets a reputation for such behavior, it will unintentionally ward off future deals and other forms of foreign investment – including those investments the state might desperately need. Such actions could lead to potentially lower levels of M&A more generally for that country, or for that particular industry – because, if the potential cost of a transaction is seen as insurmountable or unprofitable, it will not be attempted in the first place.

The widespread misuse or abuse of state intervention into foreign takeovers could also have a potentially negative impact on cross-border M&A activity globally. Repeated politicization of foreign takeovers could, for example, contribute to a backlash against globalization more broadly. In conjunction with (or as a result of) already heightened anti-globalization sentiment in a number of states worldwide, this could lead to a deceleration of economic integration and interdependence, with all of the attendant negative economic effects and foregone gains of trade and investment that would entail.

Economic Crisis and Non-Military Internal Balancing

In times of economic crisis, the issue of the correctly calculated use of non-military internal balancing is even more acute, because the potential costs of miscalculation are magnified. The failure to strike a balance between an open system of foreign investment and non-military internal balancing could certainly result in unforeseen consequences. As already discussed, depending on the states involved, and the degree and intensity of the problems triggered, overbalancing could contribute to a slow-down in cross-border M&A levels globally, impacting on globalization and, potentially, the growth of the countries involved.11

The issues examined in this work are of particular concern in light of the current economic climate, where the stability of the international economy already faces a number of challenges. The sudden and severe contraction in the credit market in 2008 meant that many states needed to nationalize failing banks and bail out foundering companies in order to stabilize their economies. Combined with potential deflation, the situation raised the possibility of currency crises in Europe and Asia. The general lack of ready financing and capital within the system during the crisis also had an unmistakable impact on cross-border M&A, whose numbers severely declined at its onset, and are only just beginning to approach pre-crisis levels. In fact, “global merger volume dropped by almost a third in 2008, ending five years of deal growth” (Hall Reference Hall2008). By 2015, cross-border M&A globally had still not recovered to the record highs of the pre-crisis period, reaching only 70% of the value and 83% of the volume of 2007 levels. In such a situation, states need to be careful not to misuse the tool of intervention in a manner that would impact the international economy by shrinking M&A values and volumes even further.

It is important to understand that lower global levels of cross-border M&A will not change the role that unbounded, bounded, and internal intervention play as a tool of non-military internal balancing. For, it is true that there was a higher level of both intervention and M&A in the recent period of pre-crisis economic prosperity, but that correlation may correspond to the evolving nature of power and/or the fact that there were simply more opportunities for the world to take notice of such activities. Either way, it can be expected that economic competition will only intensify in future times of scarcity. As private-sector M&A activity levels off, it will be government-subsidized, owned, or controlled companies that have the cash and financing to pursue cross-border deals. Indeed, a number of SWFs provided liquidity during the recent global financial crisis by making substantial investments or taking stakes in troubled banks and financial institutions, though these were not 100% acquisitions or takeovers (see Bortolotti et al. Reference Bortolotti, Fotak, Megginson and Maracky2009; Lenihan Reference Lenihan2014). Thus, one should not be surprised to see an increasingly high proportion of government activity within cross-border M&A during future economic downturns, especially given increasing state involvement in the banking sector. As a result, there may even be a rise in the use of foreign takeovers to enhance state power and a corresponding increase in the use of government intervention into such actions as a form of internal balancing.12

Policy Implications

States that wish to strengthen the foundations of the liberal economic order must make a choice to use such tools of balancing wisely and judiciously – especially in times of financial crisis or widespread resurgent economic nationalism. The general gains from FDI are vital to a state's economic power; so, if that economic power is important to them – and it clearly is – policymakers will have to find a balance moving forward between intervention into foreign takeovers and encouragement of them. If governments find themselves, in times of either severe competition or prosperity, using the intervention tool more often, then they must do so prudently.

This may mean increasing the institutionalization of the intervention process where possible, and making it more transparent so that potential acquirers know what to expect. The US, for example, has arguably already moved toward better transparency of the intervention process. The Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA), which went into effect in October of 2007,13 amends previous US law regulating foreign acquisitions of US assets in such a way as to further clarify not only the review process and procedures for foreign acquirers, but also the national security criteria on which transactions will be judged.14 One of the effects of the new regulations implemented under FINSA is that they arguably make the process more user-friendly, both for the US in terms of achieving its national security goals and for the companies that seek to navigate the CFIUS process successfully (see e.g., Plotkin et al. Reference Plotkin, Fagan and Chambers2009). In other words, making the review process less opaque should be good for business. Transactions will not drop in numbers because of fears that intervention will occur when necessary, but they will drop in the face of the inappropriate use of intervention.

Largely in response to the need to foster such good practice following the rise of intervention on national security grounds, the OECD began its Freedom of Investment process in 2006. This provides an ongoing forum for policy coordination and information exchange among over fifty governments.15 As part of this process, in 2009 the OECD Council adopted the Guidelines for Recipient Country Investment Policies Relating to National Security. As in treaty and custom, these Guidelines recognize that “essential security concerns are self-judging” and that “each country has a right to determine what is necessary to protect its national security” (OECD 2009, 3). At the same time, they encourage and

recommen[d] that, if governments consider or introduce investment policies…designed to safeguard national security, they should be guided by the principles of nondiscrimination, transparency of policies and predictability of outcomes, proportionality of measures and accountability of implementing authorities.

As states become more open to foreign investment generally, and as the political environment and security context evolve, adopting such principles will help states to navigate the challenge of walking the tightrope between openness and safeguarding both national security and power.

Concluding Thoughts

The theory of non-military internal balancing provides valuable insights for theorists and policymakers alike. On the theoretical front, the solution to the puzzle explored in this book contributes to our understanding of the political economy of international security, and provides international relations theory with yet another take on the relationship between conflict, competition, and interdependence. For the businessman, this theory may help to show where transactions are more likely to be accepted, and where they are not. For governments, a better understanding of the type of behavior examined here should contribute to a lower level of miscalculation and misunderstanding in their relations with other states regarding these matters.

For policymakers, this book has highlighted some of the true limits of globalization. This is key, because a member of a government that wishes to promote a deepening of global economic integration will need to understand where that is possible, and where it is not. Additionally, a more complete understanding of government intervention into foreign takeovers could help policymakers to avoid an unnecessary slowdown of globalization, which would have a negative impact on the economic welfare of all states. Given the nature of the recent global economic crisis, higher global levels of (economic) nationalism, and the potential for a systemic change in the balance of power in the near future, the US and other Western states may seek to re-examine how to institutionalize their values for the future. This is not only because they may not be the dominant powers in the next system, but also because the next list of great powers is likely to include countries such as Russia and China, whose economies are not yet completely liberalized. In such a scenario, understanding the limits of the free market, as demonstrated by the theory presented here, may contribute to the West's ability to entrench liberal economic principles in the next iteration of the international economic order.