Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

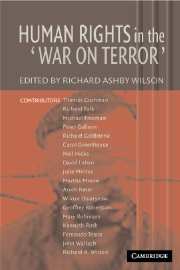

- HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE ‘WAR ON TERROR’

- Introduction

- 1 Order, Rights and Threats: Terrorism and Global Justice

- 2 Liberal Security

- 3 The Human Rights Case for the War in Iraq: A Consequentialist View

- 4 Human Rights as an Ethics of Power

- 5 How Not to Promote Democracy and Human Rights

- 6 War in Iraq: Not a Humanitarian Intervention

- 7 The Tension between Combating Terrorism and Protecting Civil Liberties

- 8 Fair Trials for Terrorists?

- 9 Nationalizing the Local: Comparative Notes on the Recent Restructuring of Political Space

- 10 The Impact of Counter Terror on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights: A Global Perspective

- 11 Human Rights: A Descending Spiral

- 12 Eight Fallacies About Liberty and Security

- 13 Our Privacy, Ourselves in the Age of Technological Intrusions

- 14 Are Human Rights Universal in an Age of Terrorism?

- 15 Connecting Human Rights, Human Development, and Human Security

- 16 Human Rights and Civil Society in a New Age of American Exceptionalism

- Index

- References

16 - Human Rights and Civil Society in a New Age of American Exceptionalism

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 August 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE ‘WAR ON TERROR’

- Introduction

- 1 Order, Rights and Threats: Terrorism and Global Justice

- 2 Liberal Security

- 3 The Human Rights Case for the War in Iraq: A Consequentialist View

- 4 Human Rights as an Ethics of Power

- 5 How Not to Promote Democracy and Human Rights

- 6 War in Iraq: Not a Humanitarian Intervention

- 7 The Tension between Combating Terrorism and Protecting Civil Liberties

- 8 Fair Trials for Terrorists?

- 9 Nationalizing the Local: Comparative Notes on the Recent Restructuring of Political Space

- 10 The Impact of Counter Terror on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights: A Global Perspective

- 11 Human Rights: A Descending Spiral

- 12 Eight Fallacies About Liberty and Security

- 13 Our Privacy, Ourselves in the Age of Technological Intrusions

- 14 Are Human Rights Universal in an Age of Terrorism?

- 15 Connecting Human Rights, Human Development, and Human Security

- 16 Human Rights and Civil Society in a New Age of American Exceptionalism

- Index

- References

Summary

What does it mean to be a human rights advocate in an age of extreme American exceptionalism? More broadly, what role can civil society play in supporting human rights goals and combating exceptionalist policies? American exceptionalism has a long history, and human rights advocates have continually struggled against it, but three factors have made human rights practice extraordinarily difficult in our post-Cold War, post-September 11 era: (i) American military and economic supremacy and a willingness and ability to use it unilaterally to advance U.S. interests; (ii) American disregard for international institutions and international norms, with unparalleled intensity and consistency, and (iii) the co-option of human rights talk by the government to serve narrow state interests contrary to human rights principles. Advocates for human rights in civil society must address all three of these factors, but this brief essay will focus on efforts to address the third factor, namely, the co-option of human rights discourse by the government and the challenge this poses for human rights advocates.

This discussion is divided into three parts. First, it begins by describing the state of the United States in the immediate aftermath of the election of George W. Bush to a second term as president. This part serves as an introduction to some of the key challenges confronting human rights advocates in light of government intrusions on civil liberties post-September 11th.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Human Rights in the 'War on Terror' , pp. 317 - 334Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2005

References

- 2

- Cited by