What’s going on in glaciology? Q&A with Graham Cogley: Part One

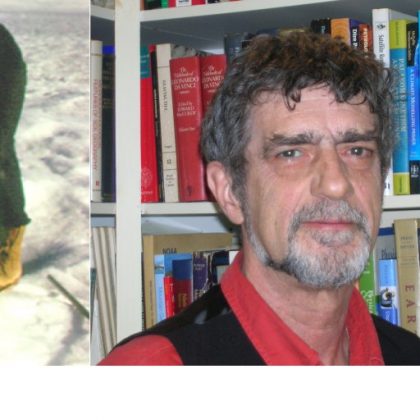

In this blog Graham Cogley, new Chief Editor of the Journal of Glaciology and Annals of Glaciology, answers questions on the most exciting recent glaciological research and where the subject should go next.

What is the most exciting research currently going on in glaciology?

One of the best things about being a scientist is that all of it is exciting. There is no research going on now that is not exciting to at least one glaciologist. As a reviewer and editor, I have noticed that even dull-sounding manuscripts get more and more interesting the further one reads. Sometimes the interest arises from a suspicion that something is wrong with the work being reported, but more often one simply wants to know how the story is going to end. But I don’t want to dodge the question. In my view the most exhilarating recent event in (or near) glaciology was the appearance in Nature (2016, 534, 79-81 and 82-85) of two papers each arguing convincingly that the molecular-nitrogen ice on the surface of Pluto is convecting. The authors were planetologists, but we – by which I really mean T.J. Hughes (1976, Journal of Glaciology, 16(74), 41-71) – were 40 or more years ahead of them. I admit this is a bizarre answer, because the opinion of nearly all qualified dynamicists is that convection does not happen in the Antarctic Ice Sheet. But if Hughes is mistaken, why? Would there be diapirs or convective rolls were it not that basal meltwater is much better at evacuating heat than we have assumed?

Where should glaciological research go next?

It should take Stephen Leacock’s advice, and get on its horse and gallop off in all directions. There is so much to do and so little time before most of the glaciers have disappeared or shrunk radically. So many unsolved intellectual problems: Why do so few glaciers surge? Why does liquid water make such an enormous difference in the behaviour of bodies of frozen water? Does a bed that slopes inland really imply catastrophic retreat of tidewater outlet glaciers, and how did they reach their advanced positions in the first place? Equally persistent practical problems such as quantifying the irreversible loss of upstream water resources in dry regions, or in humid regions that rely on glaciers for hydroelectric power; the risk of the moraine dams of proglacial lakes failing without warning; and the likelihood that snow avalanches will become more serious hazards in a warmer climate. These are problems on the human scale, faced by mountaineers, villagers in remote valleys, and all people living in glacierised drainage basins. But we all know now that the human scale covers the whole planet, and glaciologists should continue to be pioneers in the development of “big” projects – Envisat, GRACE, IceSat and the like – that have transformed our ability to monitor glaciers at the global scale.

Join us next Tuesday for Part Two of the Q&A with Graham Cogley. Next time Graham will answer the questions How is climate change affecting glaciology? and How are glaciers affecting global sea level?

In January 2016 Journal of Glaciology and Annals of Glaciology became fully Gold Open Access. This means all articles published in the 2016 volumes and beyond will be published on an Open Access basis enabling free access for all to these leading earth science journals.